The General Assembly shall consist of all the Members of the United Nations.

—UN Charter

The General Assembly is a principal organ of the United Nations, its main deliberative body. Since the UN’s founding in 1945 the assembly’s membership has grown fourfold, from 51 original members to 99 in 1960, to 159 in 1990, up to its current total of 193 when South Sudan joined the UN in 2011. It typically deals with a varied and large number of agenda items during its annual three-month session, held from September to December. For many, the General Assembly is synonymous with the parade of world leaders who travel to New York each fall to address the UN body to offer their perspective on important issues of the day. Its real role, of course, is much more complicated than that.

Both more and less than it appears, the General Assembly was modeled on national parliaments, yet it has a global purview and visibility that no national legislature can match. It is a place where the UN’s 193 member states, each having one vote, can address almost anything imaginable. The UN Charter assigns the General Assembly authority to consider all matters relating to any international issue and any UN body or agency. The assembly commissions studies about international law, human rights, and all forms of international social, economic, cultural, and educational cooperation.

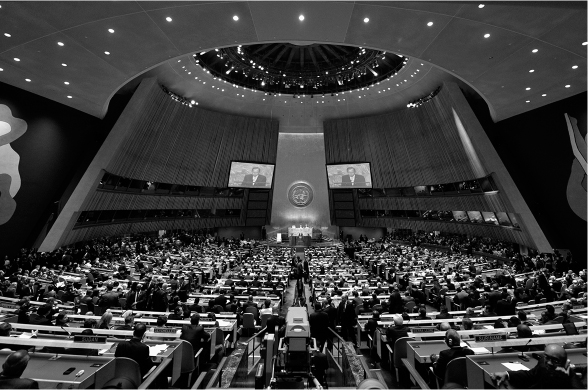

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (shown on screens) presents his annual report to the General Assembly at the opening of the general debate of its sixty-sixth session, September 21, 2011. UN Photo / Mark Garten.

Despite the assembly’s global representation, its resolutions are recommendations and are legally binding only when they apply to UN internal matters. Those domains where it has binding authority are fundamental to the UN’s operations. The assembly approves budgets and decides how much each member state should contribute. It also elects the rotating members of three principal organs, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, and the Trusteeship Council. In collaboration with the Security Council it elects the judges of the International Court of Justice and appoints the secretary-general.

Under some conditions the Security Council may ask the General Assembly to meet in special session, and such sessions can also be requested by a majority of member states. Issues deemed more pressing may warrant an emergency special session of the assembly, convened on twenty-four hours’ notice at the request of the Security Council or a majority of member states.

The General Assembly starts its official year with opening sessions, usually on the third Tuesday of each September. A week later, at the general debate, which typically lasts about two weeks, world leaders address the assembly on issues they consider important.

It is impressive to see the gathering of nearly two hundred heads of state and high dignitaries, some wearing national garb. (For a list of member states see appendix C.) Nowhere else can so many of the world’s leaders meet and exchange views, both publicly and privately. Before and after the speeches the air is thick with talk, as presidents, kings, and prime ministers use this rare opportunity to talk with scores of their peers on the sidelines of the assembly.

Then the dignitaries leave and the members get down to substantive work, which lasts until mid-December. For the 68th session, which began in September 2013, the agenda ran to 173 items, arrayed under nine broad categories, from (A) “Promotion of sustained economic growth and sustainable growth” to (I) “Organizational, administrative and other matters.” The last category includes finances and runs from item 111 to item 173. Category H, “Drug control, crime prevention and combating international terrorism in all its forms and manifestations,” is surprisingly brief (items 108–110), but G, “Disarmament,” is extensive, running from items 88 to 107, with some items having many subsections. Under “Maintenance of international peace and security,” we find some very general items, like “Situation in the Middle East” and “Question of Palestine,” which offer possibilities for endless debate, interspersed with items that come out of another era, like “Consequences of the Iraqi occupation of and aggression against Kuwait” and “Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples.” Of particular interest to American readers may be the item “Necessity of ending the economic, commercial and financial embargo imposed by the United States of America against Cuba,” which appears regularly on the agenda. These are only a few of the many topics, major and minor, new and outdated, relevant and irrelevant, political and apolitical, that define the GA’s work after the general debate. There are some pressing topics here, but you need to sift through the pile to find them.

General Assembly affairs are marked by a consuming passion for giving every member state some part of the action. There is a strong feeling that everyone should participate in as many decisions, committees, and issues as possible. As a longtime UN insider, Jeffrey Laurenti, observes, “The UN is not a place where the notion of the small getting out of the way of the bigger has much traction. There is a high premium on schmoozing small and mid-level states.” The parliamentary and administrative structure of the assembly reflects and embodies this need. At the beginning of each new General Assembly session, the members elect a president, twenty-one vice presidents (yes, twenty-one), and the heads of the six Main Committees that largely run the assembly.

Regional and national rivalries affect the politically charged voting for these positions. Formal and informal mechanisms ensure that the prerogatives and rewards of office are spread around. The presidency, for example, is rotated annually according to geographical region. If a member state from the Latin American and Caribbean region has the presidency one year, a member state from another region must have it the next year. This produces a certain inefficiency that is tolerated because of its perceived greater good.

The speeches and debates of the full General Assembly often make good media events and excellent political theater, but they are not necessarily effective means of examining issues in depth and arriving at solutions. For that, the assembly relies heavily on a clutch of committees: a General Committee, a Credentials Committee, and six Main Committees. Committees are common in legislatures worldwide because they enable many issues to be examined simultaneously. In the US Congress, committees consider legislation in the form of “bills,” which become “laws” when passed by the House and the Senate and signed by the president. General Assembly committees call their bills “resolutions.” Each committee deliberates during the assembly session, votes on issues by simple majority, and sends its draft resolutions to the full assembly for a final vote. General Assembly resolutions, even when passed by vote, are recommendations, not laws, and are not binding.

The General Committee consists of the president, the twenty-one vice presidents, and the heads of the other committees. The Credentials Committee is responsible for determining the accredited General Assembly representatives of each member state. This is usually a pro forma matter except when a nation is divided by civil war and two delegations claim the same seat. Then this normally unobtrusive committee becomes the locus of intense politicking and high emotion. An example involved Afghanistan, where the sitting delegation was challenged by the Taliban regime when it seized power. The Credentials Committee listened to presentations by both sides and then “deferred consideration,” effectively confirming the old delegation without explicitly rejecting the claim of the other one. Such sidestepping, or action through inaction, is a classic political ploy.

Each of the six Main Committees has both a number and a name, and either may be used to describe it, but insiders usually use only the number. First Committee (Disarmament and International Security) considers resolutions about global security and weapons of mass destruction, as well as more conventional weapons. Second Committee (Economic and Financial) is responsible for examining economic and social development and international trade, including the reduction of barriers that prevent developing nations from reaching their full export potential. Third Committee (Social, Humanitarian, and Cultural) is concerned with a hodgepodge of issues ranging from disaster relief to human rights. It also deals with international crime, including drugs, human trafficking, and money laundering, as well as government and business corruption. Fourth Committee (Special Political and Decolonization), despite its name, no longer addresses decolonization because there are no more colonies. Instead, it has made peacekeeping its primary mission. The committee also oversees the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Fifth Committee (Administrative and Budgetary) oversees the UN’s fiscal affairs and drafts the resolutions for the general budget that the General Assembly votes on. Sixth Committee (Legal) oversees important legal issues, such as human cloning, international terrorism, and war crimes.

One of the General Assembly’s most significant functions is to serve as a starting point for the many UN treaties (also called “conventions”). As David Malone notes, “The treaties matter tremendously in the conduct of international relations.” They matter because most nations take them seriously and because they cover such a broad range of issues, from the welfare of children to protection of the natural environment. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example, signed by member states in 1989, recognizes the human rights of persons under age eighteen. Another treaty is the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, whose purpose is pretty obvious; it was adopted by the General Assembly in 1984. The Convention to Combat Desertification in Those Countries Experiencing Serious Drought and/or Desertification, Particularly in Africa has an environmental and economic focus. Its aim is to mobilize governments and resources to protect livable lands from becoming arid. Adopted in Paris in 1994 by an intergovernmental negotiating committee, it was signed by most UN member states within a few years. Yet another treaty is the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, adopted by the General Assembly in 2006 and available for signing by member states in March 2007. It acknowledges the right of all persons to participate fully in modern society, no matter their mental or physical limitations.

Any UN body can provide the impetus and organizational structure for a treaty. The World Health Organization (WHO), for example, entered the treaty arena in 2005 when it became the main actor in passage of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). Adopted by the World Health Assembly on May 21, 2003, and entering into force on February 27, 2005, it was developed to address the globalization of the “tobacco epidemic” by recommending measures to reduce the consumer demand for tobacco products, such as setting higher prices, imposing taxes, and promoting public education about the dangers of tobacco use. WHO has used the convention to formulate a series of measures designed to reduce global tobacco use and thereby protect public health.

A member state becomes a party to a treaty by formally “consenting to be bound” by its terms, usually through the ratification of the treaty, if the treaty is still in the process of being approved by member states, or by “accession” to it if it is already in force. A treaty or convention comes into force once it has been ratified by a sufficient number of UN member states. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, to cite one instance, entered into force on September 2, 1990, a month after the twentieth member state ratified it. For those twenty states, the convention then became a fact of law, and as more states ratified or acceded to the treaty, they too became bound by its terms.

Typically a treaty has an oversight committee, called the convention secretariat, which monitors implementation. Among the duties of the fifteen-member WHO FCTC Convention Secretariat, for example, is to collect regular reports from signatories of the convention, which it makes public. All of this activity occurs under the general oversight of the General Assembly.

One of the more contentious aspects of the General Assembly has been the presence of large voting blocs consisting mainly of developing member states. The UN Charter lays out a two-tier system of voting: important matters like budgets and admission of new members require a two-thirds majority vote to pass, whereas others need only a simple majority. That seems straightforward, except when it collides with the assembly’s preference for resolving issues through consensus. Consensus happens about 85 percent of the time, but the process can be slow when nearly two hundred delegates are involved, and according to many UN insiders, the voting blocs only make the process slower.

Nancy Soderberg complains that “it’s very difficult to be in the General Assembly because everything is done by consensus.” Any decision represents “the lowest common denominator of 193 divergent countries, which is a pretty low standard.” This means that the assembly effectively cedes decisive action to the Security Council. As Soderberg says, “Everyone pretends that they don’t want to be run by the Security Council, but the key agenda is run by the council. The assembly can put out resolutions on laudatory, amorphous goals, but if you’re really going to have an impact and do things, do it through the Security Council.”

Insiders like Soderberg, accustomed to the relative speed and decisiveness of the Security Council, chafe at the inefficient and polarized approach in the General Assembly, which they attribute to two large voting blocs, the Nonaligned Movement (NAM), established in 1961, and the Group of 77 (G-77), established in 1964.

The Nonaligned Movement emerged during the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union competed for influence in the world that was emerging through decolonization. Several nations, including India and Yugoslavia, sought to define a middle path that was not aligned with either great power. In those days most NAM members were more closely associated with the Soviet Union than with the United States, recalls Pakistan’s former permanent representative Munir Akram, but now “the NAM is more nonaligned than formerly.” One member, India, regards itself as a major world power, whereas China, which certainly sees itself as a major power, is not a member of the Nonaligned Movement but works closely with it.

The Group of 77 was established “to coordinate the position of developing countries on trade and development issues,” explains Akram. It gradually acquired a sense of identity. “There is diversity in this group,” he says, “but there is a sense that on systemic issues of international economic relations their interests are not identical, but convergent, in the sense that all of them have an interest to change the present system of trade, finance, and technology control, because they feel that it is weighted against them or structured in ways that place them at a disadvantage.”

The G-77 has a more institutionalized structure than the NAM and is situated within the UN framework. It describes itself as “the largest intergovernmental organization of developing countries in the United Nations,” with the goal of enabling “the countries of the South to articulate and promote their collective economic interests and enhance their joint negotiating capacity on all major international economic issues within the United Nations system, and promote South-South cooperation for development.”

The G-77 and the NAM exercise power through numbers. In 2013 the NAM had 114 members and 17 observers, and the Group of 77 had 133 members. Add up the numbers and you get 247 members, whereas the UN has only 193, so obviously there is much overlap between the two organizations. The point is that these two bodies can control votes in the General Assembly when they choose to.

Soderberg accuses the blocs of being out of step with current realities. “Look at the Nonaligned Movement,” she says. “What are they nonaligned against now? There is no alignment, which means that they are really trying to oppose the United States more often than not, which makes no sense.” Richard Holbrooke shared her exasperation. The Nonaligned Movement and the G-77 do tremendous damage because they “just don’t serve the interests of most of their members. They are two groups that are pulled by old-school politics.”

Akram has a very divergent take on this. A former head of the G-77, he complains that the Security Council is marginalizing the General Assembly through its continual accumulation of power. While admitting some of the criticisms leveled at the assembly—“their resolutions are too long, there are too many reports, there are too many items, that’s all true”—he responds that “the same could be said of the Security Council,” which “repeats many things that are in previous resolutions.” Akram further argues that the Non-aligned Movement and the Group of 77 are potentially vehicles for positive change. The G-77 “can often coordinate its position and take common positions,” and it benefits also from a new sense of confidence among the developing countries, in part because a number of them have had successful economic growth and a number are so-called emerging economies. From Akram’s perspective, the NAM and the G-77 can potentially contribute to the UN’s evolution, as well as to global social and economic development.

Just as clearly, John Bolton says, the regional bloc system “is a contributing factor to the ineffectiveness of the UN because it helps reinforce the status quo and becomes a way for countries to protect and get part of the benefits that accrue from the UN programs. It leads to a scratch-my-back-and-I’ll-scratch-yours philosophy. That makes it unlikely you’re going to have very effective change or reform.”

Ironically, most of the nations that constitute the G-77 came into existence because of a global movement that the United States strongly supported. The word “decolonization” was on everyone’s lips from the 1950s through the 1970s, when some eighty new nations emerged from the ruins of the empires of Belgium, France, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and others. After World War II, nationalist uprisings and resistance movements challenged the colonial world order and forced out the ruling nations or persuaded them to relinquish authority. The United States encouraged the UN to be a key player in ending colonization. In fact, one of the most important UN staff members working on anticolonialism was an African American diplomat, Ralph Bunche, who had joined the State Department in 1945 and worked in the San Francisco conference that helped organize the UN that spring.

Insider Brian Urquhart, who knew Bunche well, describes him as the “dynamo” of the decolonization movement “because he knew more about it than anybody else did, including most European colonial experts.” Secretary-General Trygve Lie assigned him to the Middle East, where the UN was brokering Britain’s withdrawal from its League of Nations mandate in Palestine while the resident Jewish population was laying foundations for the new state of Israel. For his central role in negotiating a general settlement among the Israelis, British, Egyptians, and other interested powers, Ralph Bunche was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950.

Heads of state and global leaders at Rio+20, the UN Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio de Janeiro, June 20, 2012. UN Photo / Mark Garten.

The end of colonialism changed the world, and much faster than anyone expected. Decolonization also transformed the UN. The original UN had some fifty member states and operated like a small club. During the decades after 1945, the addition of so many new nations helped produce the Nonaligned Movement and the Group of 77.

The General Assembly sponsors and hosts conferences, many of which have played a key role in guiding the work of the UN. Since 1994, the UN has held more than a hundred conferences around the world on a variety of issues. High-profile meetings on development issues have put problems like poverty and environmental degradation atop the global agenda. In an effort to make the meetings into global forums that will shape the future of major issues, the UN has encouraged participation of thousands of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), experts, and others not formally associated with the UN.

A landmark conference that continues to redefine the UN’s mission was the Millennium Summit in September 2000, convened as part of the fifty-fifth session of the General Assembly designated the Millennium Assembly (September 12–December 23, 2000); follow-up conferences were held in 2005, 2010, and 2015. The lofty Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which all member states agreed to meet by 2015, are discussed in chapter 14. To cite only two of many other examples, in 1992, the UN convened a conference on sustainable development known as the Earth Summit, with a major follow-up conference known as Rio+20 in 2012.

Like all parts of the UN, the General Assembly is not separate unto itself. It functions as one very significant element in a much bigger entity, in collaboration (and sometimes competition) with the Security Council and the Secretariat, to advance an agenda that is set forth annually and is ultimately defined by the overarching mission of the world body. If life were as simple as an organizational chart, we might now imagine a straightforward, if complicated, schematic of the UN, like the one in chapter 1, and declare that we have solved the puzzle of what the UN is. Except that we must also consider that odd bit of real estate called the UN Village.