Development, after all, is about people. Their aspirations and ambitions must shape our policies and goals. I am determined to make sure that what a farmer says in Tanzania, or a student says in Vietnam, or a mother says in Honduras, will be heard at UN Headquarters.

—Ban Ki-moon, secretary-general of the UN

From its beginning the UN has been committed to improving the lives of poor, disadvantaged, and neglected people, no matter where they may live. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights describes access to adequate food, housing, education, and employment as rights, not privileges or commodities. The UN’s development focus is to “help nations work together to improve the lives of poor people, to conquer hunger, disease and illiteracy, and to encourage respect for each other’s rights and freedoms.” Given the large number of poor member states in the UN—they are actually a majority—this expansive notion of rights, which includes social and economic aspects, is pretty much taken for granted at the world body.

So varied and numerous are the UN’s social and economic development efforts that they sometimes seem to operate in their own individual worlds, leading to a dispersion of effort that may reduce or limit their impact. It was to help bring cohesion to development efforts that in 2000, Secretary-General Kofi Annan urged the member states to create a single campaign that would highlight the UN’s development efforts and provide realistic long-term goals. That, he argued, could help make the best use of the limited funds and staff at the UN organizations, commissions, funds, and other entities. The world’s leaders accepted his challenge at the General Assembly in New York City on September 8, 2000, when they launched the Millennium Development Campaign. It was defined as a fifteen-year campaign focused on improving living standards by targeting eight goals:

• Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

• Achieve universal primary education

• Promote gender equality and empower women

• Reduce child mortality

• Improve maternal health

• Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

• Ensure environmental sustainability

• Develop a global partnership for development

All members of the UN family were expected to address the goals of this, the UN’s most ambitious development effort. World leaders reconvened at a follow-up summit in New York in 2005, and again in 2010, to review progress in reaching the goals by 2015.

In brief, member states resolved that during the campaign they would reduce by half “the proportion of the world’s people whose income is less than one dollar a day and the proportion of people who suffer from hunger and . . . to halve the proportion of people who are unable to reach or to afford safe drinking water.” They also pledged to ensure that “children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling and that girls and boys will have equal access to all levels of education.” Other pledges focused on health care: to reduce “maternal mortality by three quarters, and under-five child mortality by two thirds, of their current rates,” and to stop and begin to reverse “the spread of HIV/AIDS, the scourge of malaria and other major diseases that afflict humanity.”

Josaia V. Bainimarama, prime minister of the Republic of Fiji, addresses the opening of the special event “Towards Achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs),” organized by the president of the General Assembly, September 25, 2013. UN Photo / Rick Bajornas.

The member states acknowledged the key role of women in addressing these problems, and they declared their commitment to “promote gender equality and the empowerment of women as effective ways to combat poverty, hunger and disease and to stimulate development that is truly sustainable.” The need for addressing the interrelatedness of issues appears in another pledge: “to develop strong partnerships with the private sector and with civil society organizations in pursuit of development and poverty eradication.” And this in turn tied in with the establishment of free and open political systems. “We will spare no effort to promote democracy and strengthen the rule of law,” declared the member states, “as well as respect for all internationally recognized human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to development.” This led them inexorably to their promise “to respectfully uphold the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. To strive for the full protection and promotion in all our countries of civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights for all.”

A good place to start when considering the Millennium Development Goals is the UN Development Program (UNDP), which has existed almost since the beginning of the world body and is recognized as a leader in social and economic development efforts around the world. One of the important services rendered by the UNDP is the publication of data about the status of social and economic development across the globe. The annual Human Development Report has been issued since 1990, and each report focuses on a theme. For 2013 the theme was “The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World.” The report noted the rapid improvement in living standards and other key indicators for residents of many developing countries, often referred to as the South to distinguish them from the generally well-developed nations, most of which lie north of the equator. Progress was made despite the worldwide recession of 2008.

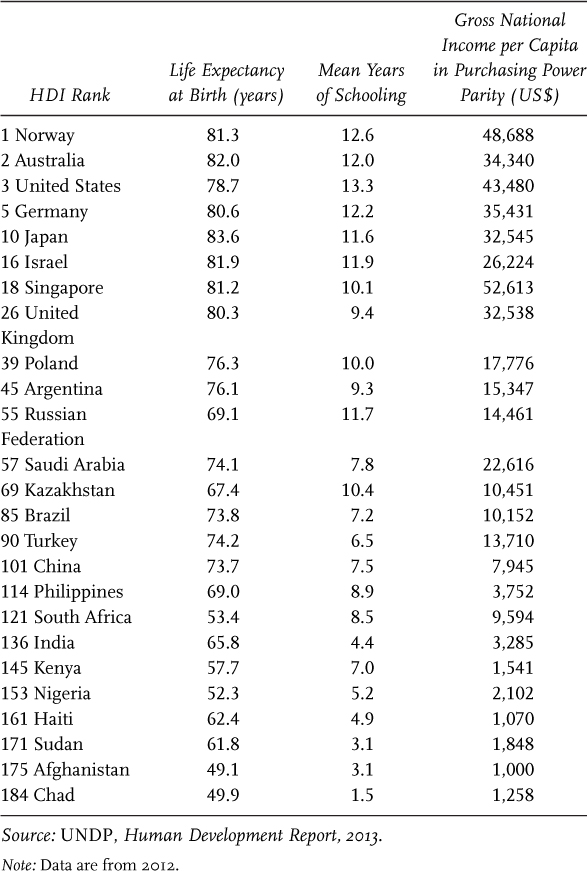

The Human Development Report also includes the Human Development Index (HDI), which rates each country’s place on a scale of social and economic development. The index addresses a wide range of sectors, from health to education to environmental quality, but it also presents a single HDI rating that ranks nations from most to least developed. Not surprisingly the United States sits very high, in third place (table 5).

The UNDP sees itself as a partner with nations that want to reduce poverty, achieve democracy, prevent disasters and recover from them when they occur, protect the environment, and gain adequate access to energy for sustainable development. In pursuing that broad agenda the UNDP encourages “the protection of human rights, capacity development and the empowerment of women.” We can pull at the last three items to reveal what lies underneath the words.

The first item is the protection of human rights, which the UNDP seeks to advance through the building of “effective and capable states that are accountable and transparent, inclusive and responsive—from elections to participation of women and the poor.” One of its programs attacks official government corruption, which involves public servants accepting bribes to give preferential treatment to the citizens who offer the bribes. Corruption abridges human rights because it gives one citizen an unfair advantage over another: it subverts the democratic belief in equal access to rights and opportunities. Corruption is pervasive in many countries, especially poorer ones where the demand for services (like education or licenses to do business) may outstrip the ability or willingness of the government to provide them.

The UNDP chose Thailand for launching an innovative anticorruption program, one aimed at changing the basic perception of corruption from something that “everyone does” to something that shouldn’t exist at all. It partnered with Khon Kaen University’s College of Local Administration in 2012 to organize the Thai Youth Anti-Corruption Network, a student-led group that began with thirty-six students from fifteen Thai universities. The UNDP held anticorruption camps across the country to educate student leaders about the dangers of corruption and to promote responsible citizenship and civic knowledge. This led to a rally by two thousand students at the Bangkok Art and Culture Center on International Anti-Corruption Day (December 9), aimed at showing that every part of Thai society needs to fight corruption. Pleased at the results of its work, the UNDP has decided to continue its university-based anticorruption efforts by fostering the growth of campus activist organizations with links among students, academics, journalists, and civil-society organizations.

Table 5. Selected national rankings from the Human Development Index, 2012

The second item is capacity building, which is development-speak for the improvement of a government or organization’s ability to function, whether through improved information technology, staff development, or some other enhancement. It is a major issue in many developing countries owing to government indifference, shortages of funds for adequate equipment and services, and low educational attainment among large segments of the population. “Among countries with well-designed and well-funded poverty reduction plans,” the UNDP notes, “the ability to reduce poverty is still being hindered by in-country leadership and knowledge gaps, a shortage of technical and managerial know-how, and difficulties retaining talented staff in an environment with few incentives.”

The UNDP has expertise related to addressing these gaps. In Liberia, for example, it helped the government create a “national capacity development strategy” that assesses the ability of ministries and other key organizations to define and fulfill their mandates and to manage and support talented staff. The government of Tanzania asked the UNDP to partner with a foundation to establish an online information management system that could track official development assistance and link it to MDG-related results. In Namibia the UNDP helped devise guidelines for collaborative arrangements between local governments and private entities for the delivery of municipal public services. It “helped to identify the capacity gaps and to reframe the roles, rights, responsibilities, and incentives of all involved in a public-private partnership.”

The third item is the empowerment of women. A consensus has emerged among development experts that many key social and economic problems can be addressed only if women join as equal partners with men in defining the issues and fixing them.

The UN has merged several of its women-related organizations under a new office, UN Women, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. To some extent, the growing emphasis on women reflects the feminist movement, which has expanded beyond the United States and Europe to all parts of the globe, but it also reflects something even bigger: the interrelatedness of so much of what happens in the social and economic spheres. When the field of development arose decades ago, its practitioners often worked on a fairly narrow range of issues or factors. Single-focus projects were the norm, as in providing basic farm equipment or teaching simple but more effective agricultural techniques.

Such single-focus projects remain important for promoting development, but increasingly they share the stage with projects and campaigns that address a range of interrelated issues. So, for example, the UNDP began a program in Egypt’s Siwa Oasis that brought literacy to girls and women. Many of the local girls came from families too poor to provide even limited education, and there was also a traditional community bias against female education, leading to a female illiteracy rate of 40 percent. In 2008 the UNDP, using one of its funds and acting in collaboration with the Egyptian Ministry of Communication and Information Technology and several partners, including the World Health Organization (WHO), Vodafone Foundation, and a local community development association, started a program to teach girls and women literacy skills and in that way give them opportunities for new or better employment.

In addition to teaching eighty-eight hundred women how to read and write and training some to be literacy instructors, the initiative put a special emphasis on computer skills, even giving participants their own personal computers. As a result, women learned to read and write, improved their agricultural and handicraft production abilities, and acquired online marketing skills. Siwa women began to promote their products through an online store. As one woman remarked, “I found in computers life itself. Now I can read and write. I can earn my living and give my children a better life. And as a mother, I am a better role model for them to follow.” In her words we can see the connections among education, women’s empowerment, economic development, and family life—just the kind of linkage that now characterizes thinking among development experts in the UN. The development landscape is changing.

The MDGs exist in a changing world, where international status and clout now seem less concentrated in a few nations than previously. A similar dispersion is occurring in the social and economic spheres, as economic growth in Brazil, China, India, Korea, and other so-called emerging nations are redrawing the global financial picture and creating large new middle classes that long for the quality of life enjoyed in the developed nations.

Consumer-based societies are popping up all over and, with them, new markets for telecommunications, health care, transportation, education, recreation—basically all the accoutrements of modern life. “It’s all good news,” remarks Malloch-Brown, who directed the UNDP before becoming deputy secretary-general under Kofi Annan. “It shows development works.” He acknowledges that older forms of development, by which governments made large financial grants to poorer nations’ governments, are not as useful as before, nor as necessary, owing to the enlarged financial wealth and capital of many developing nations. Nowadays, he explains, government-to-government grants are largely for technical assistance “rather than the large transfer kind.” Increasingly, development assistance is coming through hybrid arrangements involving public-private partnerships or even private-private ones. “In a whole array of countries, poor and middle-income, there remains plenty of space for the new kinds of hybrid arrangements of public-private collaboration, roles for the private sector, domestic and international, in development.”

The new landscape has posed challenges for Malloch-Brown’s former agency. “UNDP is struggling with resources,” he observes, “squeezed by the rise of the very targeted single-issue global funds, whether it’s around public health or education. There is more private-sector capital now, including large foundations and NGOs, who are new actors in development.”

David Malone agrees that UNDP is feeling pressure. A former Canadian diplomat, now rector of the United Nations University in Tokyo, Malone knows the UN system from both the outside and the inside. He sees major shifts occurring as a result of the great global financial meltdown of 2008, including reduced contributions to the world body. “The Europeans are lately preoccupied with their own affairs” and are “not providing their usual energy at the UN.” Lamenting that “there are new issues but no new money,” Malone says that “a number of agencies are shrinking very fast,” among them the UNDP. Even the World Bank now faces “major operating budget cuts.”

Malone’s comment on the World Bank is significant. The World Bank Group is a major source of financial support and services to developing countries seeking to improve their social and economic conditions. Its motto is “Working for a world free of poverty,” and it pursues its goals through various strategies. One of its five components is the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which lends to “governments of middle-income and creditworthy low-income countries.” Another is the International Development Association (IDA), which provides grants and credits, that is, interest-free loans, to governments of the poorest countries. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), a third component, focuses exclusively on the private sector; it offers financial and advisory services to businesses and governments. The fourth component, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), promotes foreign direct investment by offering political risk insurance to investors and lenders. The fifth component, the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), provides international facilities for conciliation and arbitration of investment disputes.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (left) meets with Jim Yong Kim, president of the World Bank, during the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, January 23, 2014. On the right is Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson. UN Photo / Eskinder Debebe.

Historically the World Bank has been generously funded by the developed nations, especially the United States, and usually an American sits as its director, though the current director, Jim Yong Kim, is a Korean. He faces challenges in moving the bank through the new development landscape. Many developing nations now are creditworthy enough to draw on new sources of development capital and no longer have to rely as heavily on the World Bank. Some national economies are growing so fast that their capital needs are outstripping the bank’s ability to lend. The financial meltdown of 2008 only made things worse, especially when the leading developed nations cut their financial contributions to the bank. Perhaps feeling the heat, the bank has refocused itself on a campaign to end extreme poverty by 2030, with particular emphasis on raising the incomes of the poorest 40 percent in every country, even the richer ones. By doing so it is aligning itself with the poverty-reduction goals of the Millennium Development Campaign, just when the UN is trying to decide what to do for an MDG encore.

Has the Millennium Development Campaign succeeded? Like so many grand enterprises, it had its ups and downs, but on the whole it was well received. Certainly it led to more improvements in global well-being than many observers expected in 2000, when it must have seemed yet one more well-intentioned UN scheme.

During the span of the Millennium Development Campaign, global rates of extreme poverty fell by half, and two billion more people gained access to safe drinking water. The first MDG addressed the need to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger and was the first to be met. Maternal and child mortality dropped considerably (though not as much as hoped), and a record number of children were in primary school, with the number of girls equaling the number of boys for the first time. The battle with killer diseases such as malaria and AIDS made real gains. On the other hand, much work remained to be done. Global carbon emissions, a factor in climate change, rose, and forests and fisheries continued to suffer from overexploitation. Child mortality fell, but not enough. The eighth goal, creating a global partnership for development, seems to have met with the least success, except for the greater availability of essential medicines.

Despite the limitations, many observers rate the MDGs a success in providing generally acknowledged benchmarks of progress and in helping focus international development efforts (table 6). Deputy Secretary-General Eliasson rates the MDGs as “extremely useful both for global aspirations in the area of development but also translating to the national and even local levels. They have become a very effective instrument, a very effective tool of measurement of progress.”

As the MDGs neared their target date, 2015, stakeholders and others from the UN and elsewhere began reflecting on next steps. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon commissioned a panel of notable persons from around the world to offer thoughts on the post-2015 agenda. In 2013 they issued their report, A New Global Partnership: Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development. They praised the accomplishments of the Millennium Goals Campaign while also enumerating the many shortfalls and failures. A new approach was needed, they argued, based on a global partnership that would eradicate extreme poverty by 2030 and help achieve sustainable development. Despite the world’s economic growth in recent decades, they continued, the 1.2 billion poorest people accounted for 1 percent of world consumption, while the richest 1 percent accounted for 72 percent.

The authors stressed the importance of integrating various approaches into a coherent plan. The MDGs “fell short by not integrating the economic, social, and environmental aspects of sustainable development as envisaged in the Millennium Declaration, and by not addressing the need to promote sustainable patterns of consumption and production.” As a result, “environment and development were never properly brought together. People were working hard—but often separately—on interlinked problems.”

Out of this and other discussions and reports there emerged a vision for global development in the post-MDG years, from 2015 to 2030. Sustainable Development Goals—SDGs—have replaced the MDGs and will continue and expand the work already done by governments and the UN’s many development organizations and partnerships. Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger remains a prime focus, but increasing emphasis now falls on the need for sustainability. The UN’s Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals has stated that the eradication of poverty is one part of an overarching goal that also includes replacing unsustainable modes of production and consumption with sustainable ones, and protecting and managing the natural world, which is the resource base of economic and social development. The working group also remarked on how experience with the MDGs revealed the need for defining goals and outcomes carefully in order to draw useful conclusions about the effectiveness of global development efforts. Clearly, the analysts at the UN see the MDGs as a laboratory that has helped improve and refine international development.

Table 6. Millennium Development Goals scorecard, 2013: Selected highlights

Source: Compiled from The Millennium Development Goals Report 2013 (New York: United Nations, 2013), http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/report-2013/mdg-report-2013-english.pdf.

All parts of the UN system are expected to advance the SDGs. “People across the world have mobilized for the MDGs, the most successful anti-poverty push in history,” the secretary-general has declared. “Now we must finish the job and tackle a new generation of development challenges.” The intent of the UN, he said, is to create “the most inclusive global development process the world has ever known,” with the goal of empowering people and building “a better life for all while protecting our planet. This is the essence of sustainable development.”

• The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), based in Rome, is the lead UN agency for agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and rural development. In November 2013 the FAO employed 1,795 professional and 1,654 support staff. For 2014–15 the total budget was $2.4 billion, including voluntary contributions by members and other partners to support technical and emergency (including rehabilitation) assistance to governments as well as directly support the FAO’s core work.

• The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), founded in 1977, is a specialized agency of the UN based in Rome. It is mandated to combat hunger and rural poverty in developing countries by providing long-term, low-cost loans for projects that improve the nutrition and food supply of small farmers, nomadic herders, landless rural people, poor women, and others. IFAD also encourages other agencies and governments to contribute funds to these projects. The United States is one of the agency’s largest contributors.

• The International Labour Organization (ILO), created in 1919, is based in Geneva. The ILO formulates international labor standards through conventions and recommendations that establish minimum standards of labor rights, such as the right to organize, bargain collectively, and receive equal opportunity and treatment. One of the ILO’s most important functions is to investigate and report on whether member states are adhering to the labor conventions and treaties they have signed. The United States, which has a permanent seat on the ILO’s governing body, considers the organization vital for addressing exploitative child labor. A US government report claims that the programs have “removed tens of thousands of children” in Central America, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and elsewhere “from exploitative work, placed them in schools, and provided their families with alternative income-producing opportunities.” On its fiftieth anniversary, in 1969, the ILO received the Nobel Peace Prize.

• The UN Center for Human Settlements (Habitat), created in 1978, is headquartered in Nairobi. Habitat describes itself as promoting “sustainable human settlement development through advocacy, policy formulation, capacity-building, knowledge creation, and the strengthening of partnerships between government and civil society.”

• The UN Development Program (UNDP), founded in 1945, is based in New York. The UNDP concentrates on four aspects of development: poverty, the environment, jobs, and women. A US government report observed that the UNDP gives the United States an “important channel of communication, particularly in countries where the US has no permanent presence.” The United States has been the organization’s biggest donor.

• The UN Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), which became a specialized agency in 1985, is based in Vienna. UNIDO helps developing nations establish economies that are globally competitive while respecting the natural environment. It mediates communication between business and government and works to encourage entrepreneurship and bring all segments of the population, including women, into the labor force. Its staff include engineers, economists, and technology and environment specialists.

• UN Women, the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, was established in 2010 as part of the UN reform agenda. It merged the efforts of four previously distinct entities: Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW); International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women (INSTRAW); Office of the Special Adviser on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women (OSAGI); and United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM). The General Assembly gave UN Women responsibility for assisting in the formulation of policies, global standards, and norms and helping member states to implement these standards. An example of its work is the Millennium Development Goals Gender Chart, published in 2014, which assesses progress in meeting those MDGs relating to the status of women, including employment, education, maternal health, and empowerment. UN Women is also charged with holding the UN system accountable for its own commitments to gender equality.

• The World Bank was established in 1945 with the goal of reducing global poverty by improving the economies of poor nations. In recent years the bank has tried to ensure that local organizations and communities are included in projects in order to increase the chances for success. The World Bank consists of five parts, all based in Washington, DC:

1. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development began operations in 1946. It offers loans and financial assistance to member states, each of which subscribes an amount of capital based on its economic strength. Voting power in the governing body is linked to the subscriptions. Most of its funds come from bonds sold in international capital markets.

2. The International Development Association offers credit to countries with low annual per capita incomes. Most of the funds come from the governments of richer nations.

3. The International Finance Corporation is the developing world’s largest multilateral source of loan and equity financing for private-sector projects.

4. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency provides guarantees to foreign investors in developing countries that protect against losses from political factors and such other factors as expropriation and war.

5. The International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes provides arbitration or conciliation services in disputes between governments and private foreign investors.