A country’s voting record in the United Nations is only one dimension of its relations with the United States. . . . Nevertheless, a country’s behavior at the United Nations is always relevant in its bilateral relationship with the United States, a point the Secretary of State regularly makes in letters of instruction to new U.S. ambassadors.

—US Department of State

Because the United States is the biggest player at the United Nations, its words, actions, and nonactions are parsed in a hundred divergent ways by the world’s media, governments, and analysts. But people are not generally aware that the US government does its own parsing of member states’ behavior, especially their voting records. The US government places such great importance on positioning itself strongly within the UN system that it monitors how other nations vote in the 193-member General Assembly and the 15-member Security Council. Section 406 of Public Law 101-246 requires the State Department to inform Congress annually about how UN member states have voted in comparison with the United States. As the report’s introductory section notes, the Security Council and the General Assembly are “arguably the most important international bodies in the world, dealing as they do with such vital issues as threats to peace and security, disarmament, development, humanitarian relief, human rights, the environment, and narcotics—all of which can and do directly affect major U.S. interests.”

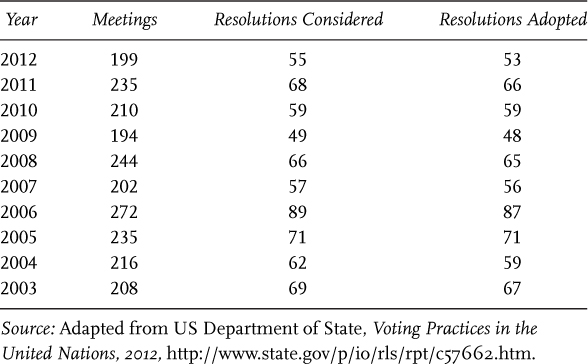

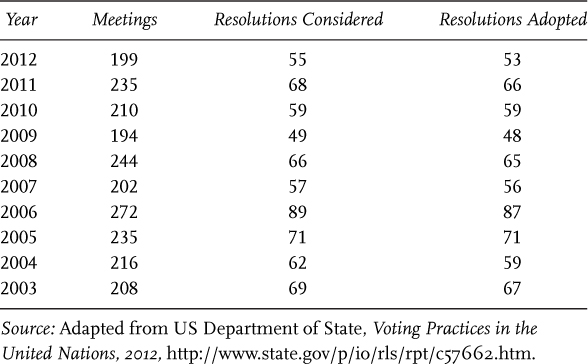

Table 7. Voting activity of the Security Council, 2003–12

Each year, the State Department’s UN analysts tote up how member states vote on the issues, whether with or contrary to the US voting position. For the Security Council, there is usually little suspense about the numbers. The tight club almost always acts through consensus (table 7). In 2012 the council considered fifty-five resolutions and adopted fifty-three, many of them unanimously. The sole vetoes were cast by China and Russia on resolutions about Syria. Only four resolutions were not adopted unanimously, one each on Cyprus, Sudan, children in armed conflict, and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Former US ambassador John Negroponte sees the strong consensus numbers as clear proof that “for all the talk about our being unilateral, the number of resolutions and issues that we succeed in dealing with on a totally consensus basis is really quite striking.”

The General Assembly passes most of its resolutions by consensus and the rest by tallied vote. When you factor in all the resolutions passed, both by consensus and by tallied vote, it turns out that in 2012 the member states and the United States voted the same way 83.9 percent of the time. The percentage has been stable in recent years: 84.3 percent in 2009; 85.4 percent in 2010; 85.9 percent in 2011. That may be unexpected, given the wide spectrum of perspectives, agendas, and interests in the assembly.

The Security Council chamber before a meeting on Afghanistan, December 17, 2013. UN Photo / Amanda Voisard.

Votes on non-consensus issues, however, show a much different pattern. During the fall 2012 session the Sixty-Seventh General Assembly held eighty-nine tallied votes on resolutions. The United States voted yes twenty-nine times, voted no forty-nine times, and abstained eleven times. Did other countries vote substantially the same way as the United States on those resolutions? Only 42.5 percent of the time, according to the State Department’s tally.

The numbers become more interesting in the State Department’s tabulation of voting coincidence by country. We can see, for example, that Afghanistan voted with the United States 36.5 percent of the time. Other percentages are Australia, 71.0 percent; Brazil, 35.1 percent; China, 30.3 percent; Germany, 60.0 percent; Saudi Arabia, 29.2 percent; and the United Kingdom, 73.8 percent.

Other tabulations show voting coincidences by region, bloc, and “eight important votes,” meaning votes on issues that the United States holds especially close to its national interest. In 2012 these eight were votes on:

• ending the US economic blockade of Cuba

• four resolutions concerning the Palestinians and Israel

• the status of human rights in Iran

• the status of human rights in Syria

• entrepreneurship for development

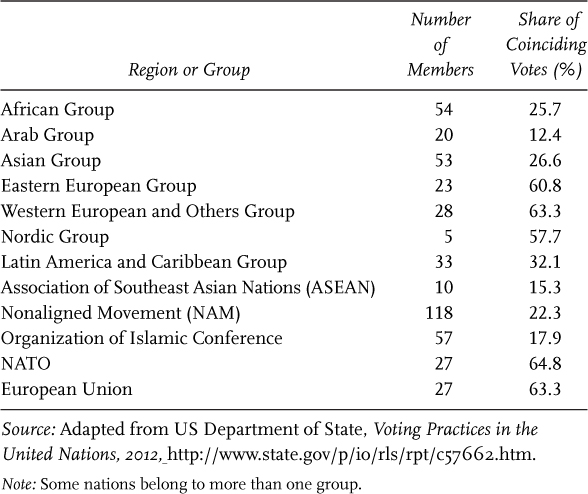

In table 8 we can see that US interests often differ from those of other governments or blocs, such as the Asian and African Groups, and to that extent we can see how the United States sits within the broader world community.

Table 8 lists basic groups. For Africa, whose fifty-four nations run from Algeria to Zimbabwe, the average voting coincidence with the United States in 2012 was 25.7 percent. After reaching a low with the Arab Group (12.4 percent), which includes Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia, among others, the numbers improve. The Asian Group, a conglomeration of fifty-three nations stretching from India to Indonesia, voted with the United States 26.6 percent of the time. Europeans were far more likely to vote with the United States: the twenty-three nations in the Eastern Europe Group, 60.8 percent of the time, and the nations in the Western Europe and Others Group, 63.3 percent. The Latin America and the Caribbean Group represented another drop in coincidence. The thirty-three members, on average, voted with the United States 32.1 percent of the time.

Another way to parse the voting is by political grouping. UN member states belong to various affinity groups, such as the OIC (Islamic Conference), ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), the Nonaligned Movement (NAM), and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The State Department annually examines how these blocs vote on issues that the United States considers important. Voting coincidence among the ten ASEAN nations averaged 15.3 percent in 2012, while for the NAM, a collection of member states ranging from little Barbados to oil-rich Saudi Arabia to the subcontinent of India, the coincidence was a little higher, 22.3 percent. NATO and the European Union were three times as likely to vote the same way as the United States.

Table 8. Voting coincidence of General Assembly groups on “eight important votes,” Sixty-Seventh General Assembly (2012)

The number of nations voting with the United States has generally risen after the marked decline during the George W. Bush administration. General Assembly voting coincidence with the United States was 18.3 percent in 2007; 25.6 percent in 2008; 39 percent in 2009; 41.6 percent in 2010; 51.5 percent in 2011; and 42.5 percent in 2012.

European nations, most of which are affluent and developed, are more likely to vote with the United States, whereas developing nations are not. In other words, the North-South divide seems to be in play. The divide’s influence may be exacerbated by another factor suggested by insider Jeffrey Laurenti. “Developing country democracies do not behave the way Washington does by dint of being democracies, or see things by dint of being democracies,” he says. “The thing that is striking, and very hard for many in Washington to understand, including many liberal voices, is that India, South Africa, and Brazil tend to see international crises more like China does than the United States does.” Laurenti’s explanation is that compared with rich and powerful countries, poorer countries “have a divergent optic. . . . So they have a tug of claims: the claim of solidarity among the poor of being able to understand things that wealthier countries don’t instinctively get, and a sense of doubt about the motivations perhaps of the rich and powerful—in many cases the rich and powerful that have colonized those same countries within living memory.”

Stewart Patrick of the Council on Foreign Affairs likewise remarks on the difference in perception. “The US loves it when the emerging powers do more in the UN as long as they agree with the US.” Often they don’t. “The difficulty is, of course, these countries actually have minds of their own and they aren’t always aligned with the US. So it’s one thing to ask them to shoulder a greater burden of global order and international good. It’s another to expect that they’re going to align with the United States.” This has caused frustration on the US side. “One US official actually said that the US sees some of these countries ‘cross-dressing.’ In some venues they’ll be in bilateral conversations with the US and they’ll be very aligned, but when you get them in the UN General Assembly they’ll play to the galleries. A lot of it has to do with the ambivalence and split political identity of some of these emerging regional and potentially global powers.”

However we interpret lesser degrees of coincidence, we are left with yet another question: What do these numbers mean in terms of American foreign policy? As the State Department’s annual report observes, although a nation’s UN voting record “is only one dimension of its relations with the United States,” it is nevertheless a significant factor and “always relevant in its bilateral relationship with the United States.” A particular aspect of that relationship is foreign aid, which some experts have argued should be linked to how a nation votes in the UN (something that Congress has not required).

Even without any formal linkage it is possible that the State Department’s report may have an effect on how other nations vote. The department sends copies to the foreign ministries and missions of UN member states as a friendly reminder that Uncle Sam is watching.