Chapter 4

The Well-Socialized Gene

THE EFFORT TO SECURE FUNDING FOR A VIETNAM WAR MEMORIAL-was inspired in part by a movie, The Deer Hunter.1 The result, despite the heated opposition of socially conservative philistines, was Maya Lin’s simple but powerful tapering black walls inscribed with the names of the war’s U.S. victims. The Deer Hunter, however, was less about those whose names appear on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, than about those who survived the war but were physically and/or psychologically wounded. In this chapter we will focus on the nature of war’s psychological wounds, so effectively depicted in this movie. Some of these wounds are epigenetic in nature. One of the reasons war and other forms of trauma have such enduring psychological effects is that they induce epigenetic alterations that cause long-term changes in gene regulation.

The Deer Hunter was released in 1978. It immediately resonated with an American audience in the process of reconciling itself to the horrible misadventure that was the war in Southeast Asia. The events in the film occur in the late 1960s, when the war was at its zenith and the country was riven by protests and counterprotests, which reflected a sociocultural, as much as political, divide in this country. The protesters were generally middle class and either in college or college educated. The counterprotesters were largely lower middle class blue-collar workers, who went to work full time right after high school. The protagonists in the movie come from the latter group. They are steelworkers in an unattractive small town south of Pittsburgh.

Michael (played by Robert De Niro) is clearly alpha, a man for whom leadership comes naturally; he embodies the kind of virtues that many Americans celebrate and deem distinctive to our culture: Decisive, action oriented, physical—the traits that helped make John Wayne a movie star and George W. Bush a president. But unlike John Wayne and George W. Bush, Michael has a reflective side. Steven (John Savage) functions as a sort of middle brother; he is loving and easygoing, about to marry a woman who is pregnant by another man. Nick (Christopher Walken) is the youngest, closest in age to the protesters. He is also distinctive in his introspection. He has an artistic sensibility that seems out of place in this group, in this town. Early in the movie, during the deer hunt, Nick says to Michael that he loves to hunt because he “loves the trees,” the way each tree is different and unique. The relationship between Michael and Nick resembles that of an older brother and a younger brother but without any of the familial complications. Michael both understands and appreciates Nick’s artistic sensibility. During the hunt, he tells Nick that “without you, Nicky, I hunt alone.”

Before the opening scene, the three friends have decided to enlist in the army—Michael, for his own reasons, Steven and Nick because Michael did so. They are soon to be deployed, but before that there is the matter of Steven’s wedding. It is a traditional Rusyn (an Eastern Slavic ethnic group) Orthodox wedding that reinforces for the viewer the fact that these men are only a generation or two removed from immigrant status. During the raucous reception, Nick asks his girlfriend, Linda (Meryl Streep), to marry him. She agrees. Michael, who is secretly attracted to Linda, gets righteously drunk later that night and runs naked through the streets of town. Nick eventually subdues him; he then makes Michael, drunk though he is, promise not to leave him “over there,” if something happens. His plea has literal and metaphorical sobering effects on Michael.

Early the next morning, Nick and Michael along with three other friends—but not Steven, who is on his honeymoon—embark on their deer hunt. The other three friends are not interested in hunting so much as getting drunk; one even forgets his boots, which greatly angers Michael, a serious hunter. In fact, for Michael, hunting has a sacramental element and the deer is a somewhat totemic figure that must be treated with respect. Hence his obsession with killing the deer with “one bullet, one shot,” which he proceeds to do.

The film jumps to a battle scene in a small Vietnamese village, during which Michael burns an enemy combatant with a flame thrower, then shoots the incinerated corpse numerous times with his M16. Reinforcements arrive, including Steven and Nick. Soon after the three friends are reunited, however, they are captured and held as POWs at a primitive facility on the edge of the Mekong River. For entertainment, their guards force the men to play Russian roulette, betting on the outcome. This is the second most crucial scene in the movie after the deer hunt.

Steven is the most outwardly, demonstratively terrified and traumatized by the prospect, so Michael focuses his attention on comforting him, hugging him, exhorting him to be strong. Steven is also chosen as the first of the three to “play.” Meanwhile, Nick cowers in quiet terror, unconsoled. Eventually Michael convinces Steven to pull the trigger. Fortunately, he aims high, as the chamber was loaded. For his transgression, Steven is placed in an underwater wooden cage, the top of which he must grab to keep his head above water. During a hiatus, Michael convinces Nick that their best chance is to play each other with three (of six) chambers loaded, rather than one. If they both survive they will turn on the captors. But now, of course, the odds of surviving are much lower. Nick is reluctantly persuaded of the plan. When the gun is spun, it points to Nick, so he is the first to go. After much hesitation during which his captors scream threats, he pulls the trigger; the chamber is empty. Now it is Michael’s turn. The tension is almost unbearable for both him and Nick. Michael steels himself and pulls the trigger. There is only a click. He immediately turns the gun on his surprised captors, and with the help of the rifle of the first captor shot, the two men manage to kill their remaining captors.

Michael, while plotting the escape, had advocated leaving the psychologically broken Steven behind, but Nick vehemently protests, so they bring him along. Once they escape the prison, they float down the river on a log until a rescue helicopter arrives. Nick is first to board, while Michael and Steven still dangle from the landing rails. Steven loses his grip and falls back into the river, Michael then lets go his own grip to rescue Steven. Michael manages to bring him to shore, then carries the now paralyzed Steven through the tropical forest until they reach a friendly convoy retreating from battle.

We next find Nick recuperating in a Saigon military hospital, showing signs of psychological damage. He can barely speak to his doctor. He does not know where his friends are. He may feel abandoned; he may feel survivor’s guilt. In any case, he is isolated and alone. He wanders the red light district of Saigon at night, where he is introduced by an expat Frenchman to a gambling den, where they play Russian roulette. Michael is in the room and suddenly recognizes Nick, but his call to his friend, as he is being whisked away, is unheard.

In the next scene, Michael is returning home, believing that Steven and Nick are dead or missing. He finds the attention and support of his friends unwelcome. He retreats into himself. When he again goes out hunting, he tracks down a trophy buck but purposely misses high. From a rocky ledge he shouts, “OK?” as if to God, but hears only echoes in reply.

Unbeknownst to Michael, Steven is convalescing in a nearby Veterans Hospital; he is partially paralyzed and has lost both legs. When Michael learns of this, he visits Steven at the overcrowded VA hospital. The reunion is marred by the fact that Steven doesn’t want to return home to his wife, family, and friends. Steven also informs Michael that he has been receiving large amounts of cash from someone in Saigon. Michael realizes that the cash is coming from Nick. He brings Steven home against his will, then departs for Saigon and arrives just before its fall in 1975. He eventually locates the French expat, who reluctantly takes Michael to Nick, his cash cow, in a seedy and crowded den. But Nick doesn’t recognize Michael, nor remember much about his life in Pennsylvania. A desperate Michael enters a game of Russian roulette against Nick, talking all the while about Pennsylvania, to no avail. But his talk of past hunting trips finally resonates. Nick recognizes Michael, smiles, and says, “One shot.” He then shoots himself in the head to Michael’s—and our—horror.

One of the strengths of the movie is the varied ways in which Michael, Steven, and Nick respond to their traumatic experiences in Vietnam; they represent a microcosm of sorts of the reactions of Vietnam veterans, or the veterans of any armed conflict, as a whole. Michael, like many—perhaps the majority—of veterans, experienced temporary depressive symptoms (and perhaps lifelong nightmares) of the sort that you would expect of any sentient being, given his experience. His response closely resembles responses typical of someone grieving the loss of a loved one. Steven suffered a more severe and long-lasting depression, as evidenced by his desire for social isolation, even from his loved ones. Nick’s psychological wounds were the most severe, true posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), though that term was not invented until a couple of years after the film was released.

But the psychic wounds of all three men have one thing in common: a problematic stress response that is at least temporarily pathological. There are two basic ways in which the stress response can go awry. First, it can be overly sensitive, too easily triggered, and hence chronically overactive. The result is various forms of anxiety disorders and depression, the problem experienced to different degrees by Michael and Steven. Second, it can react too robustly in response to a stressor, in effect blowing the circuits. This problem is more typical of PTSD as experienced by Nick.

The Stress Response

Obviously, the three friends did not have identical experiences in Vietnam—only Steven experienced the underwater prison, for example. But we will ignore these differences for the purposes of this discussion. Given this idealization, how do we explain their varying reactions to this trauma? Some people would emphasize their genetic differences; others would focus on differences in the way the three characters were raised. Most everyone, no matter what their biases, would make an ecumenical bow in acknowledging that it’s not solely genes or environment but some combination of both, a cursory suture of the nature-nurture divide. Here we will explore a more intriguing possibility—that their early environments may have caused their genes to react differently to the same stress.

It is the pathologies in the stress response that we usually think of when we think of the stress response. But the stress response is utterly vital to our normal functioning as well, a fundamentally adaptive process that evolved to help retain a physiological equilibrium when confronted with the challenges of our dynamic environment. One indication of the importance of the stress response is that it involves virtually all of our physiological systems, from reproduction to the immune response.

The fastest form of the stress response is often referred to as fight or flight, during which the heart rate increases, the blood vessels dilate, the liver breaks down the energy store of glycogen to glucose, the primary energy source for our cells. All of these events prepare the body for quick decisive action. So too do other responses involving the skin (perspiration), the immune system (repair of wounds), and the brain (arousal and vigilance). Fight or flight is the initial form of the stress reaction in response to acute stressors, from drunk drivers to bears in our path to being shot at during combat, and, yes, to Russian roulette. When the stressor is more chronic—bullying, joblessness, trench warfare, and so on—the stress reaction involves many elements of the fight-or-flight response but also longer-term changes in the activated systems.

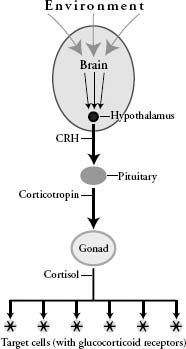

The stress response is initiated in the brain and involves two distinct but interconnected systems. Here we will focus on the so-called stress (or HPA) axis, the basic structure of which resembles the reproductive axis discussed in the previous chapter: A population of neurons in the hypothalamus produces a hormone, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates cells in the pituitary to release corticotropins (CT), which stimulate the adrenal gland to release glucocorticoid stress hormones including cortisol. Like the sex hormones testosterone and estradiol, cortisol is a steroid hormone and influences gene expression by combining with its nuclear receptor.2 There are a number of glucocorticoids. We will pretend, however, that cortisol is the only glucocorticoid, and that there is only one glucocorticoid receptor. Glucocorticoid receptors are far more abundant and distributed more widely than androgen receptors, and they activate a much greater variety of genes. For this reason, synthetic glucocorticoids, like cortisone, have even more side effects than does testosterone.

A schematic diagram of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Diagram by the author.

Stress-related pathologies occur when the stress axis is overtaxed, either by an overwhelming acute trauma like Russian roulette, or by chronic stress such as experienced by a soldier under constant threat. Whether the stress overload is acute or chronic, one of the more reliable indicators of stress is an elevation of CRH levels in the brain.3 (Cortisol levels are also often elevated, but the relationship between a pathological stress response and cortisol level is more complicated.)

Of course, there is a lot of individual variation in how we respond to stress, as represented by Michael, Steven, and Nick. This individual variation has led to a search for genes that might explain this variation, such as genes for depression and anxiety. In a quite different approach, the emphasis is on events occurring early in life, beginning in the womb.

What Happens in the Womb Does Not Stay in the Womb

For decades, fetuses at risk for premature birth have been treated with a synthetic form of cortisol to promote lung development, because respiratory failure is one of the main hazards of premature delivery.4 Recently, doctors and scientists have become concerned about the long-term effects of this treatment on the stress axis. These concerns are warranted. Fetuses that have received this treatment evidence lifelong hyperresponsiveness in the stress axis that results in a greater incidence of heart disease and diabetes, among other ailments, and a reduced life expectancy.5 These treatments also predispose the recipients to stress-related brain/behavioral problems such as anxiety disorders, depression, substance abuse, and schizophrenia.6

These synthetic glucocorticoid treatments mimic the effects of maternal stress. When a mother-to-be is stressed, she produces more cortisol than she otherwise would. Some of this cortisol is transmitted to the fetus through the placenta. The elevated cortisol levels experienced by the fetus permanently adjust the settings of the stress axis of the fetus in a way that makes it more sensitive and hyperresponsive to subsequent stressful events. These permanent alterations in the stress response are often referred to as glucocorticoid, or HPA, programming.7 Here I will simply call it “stress biasing.”

A mother’s stress could come from multiple sources. A bad marriage, social isolation, and poverty are just a few. Extreme stress levels, such as those thought to promote PTSD, can also result from diverse causes. War is a very effective promoter of PTSD, as so effectively portrayed in The Deer Hunter. Of course, the Vietnam War was not the first to produce victims of PTSD. Indeed, Herodotus, in 500 B.C., is alleged to provide the first account of this malady, in a veteran of the Greco-Persian wars who had witnessed the death of his close friend at the Battle of Marathon.8 More recently, World War I resulted in many cases of “shell shock,” and World War II, “battle fatigue,” both less clinically euphemistic names for PTSD.

War is not a prerequisite for PTSD; any severe trauma will do. Natural disasters such as earthquakes, the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean, and Hurricane Katrina are effective agents of PTSD.

Far from natural disasters, such as the 2001 destruction of the World Trade Center, have also caused PTSD.9 The true toll of the Holocaust included not only the millions who were killed or died of starvation, but also many, many survivors who were permanently damaged in a way we now recognize as PTSD. In fact, this form of suffering caused by the Holocaust continues to ramify beyond its immediate victims, in a way that may be relevant to Nick’s case.

Children of mothers who suffered PTSD as a result of the Holocaust are more prone to develop PTSD, even though they had no direct experience of the Holocaust.10 Interestingly, though all children of Holocaust survivors are more prone to depression, second-generation PTSD is only elevated in those whose mothers suffered PTSD; there is no such correlation for children whose fathers experienced PTSD a result of the Holocaust. This fact suggests an important role for the fetal environment. The role of the fetal environment is especially evident in mothers who directly experienced the destruction of the World Trade towers. As you would expect, a number of them evidenced PTSD. Those who were pregnant at the time gave birth to babies with an elevated stress response and a hypersensitive stress axis.11 They will be more susceptible to anxiety, depression, and even PTSD than those whose mothers did not experience PTSD. We would expect, then, that such traumas experienced through the womb could be a contributing factor to the susceptibility of veterans like Nick to PTSD.

PTSD is but an extreme case of a stress response gone bad, and perhaps the least well understood. Far more pervasive are stress-related pathologies such as those evidenced by Michael and especially Steven. It is to these less extreme pathologies, such as anxiety, fearfulness, and depression, that we will now turn. To get to the bottom of the mechanisms underlying these pathologies, however, we need nonhuman animal models for the necessary experiments. For in utero effects of stress, the guinea pig is the animal of choice because, like humans, guinea pigs have long pregnancies and the young are born in a developmentally advanced state compared with mice and rats.

As in humans, when pregnant female guinea pigs are treated with synthetic glucocorticoids, the stress response of their offspring can be permanently altered.12 Moreover, when pregnant guinea pigs are subjected to stress during the phase of rapid fetal brain growth, the male offspring also exhibit an elevated stress response. There are noteworthy alterations in the brain and pituitary that accompany these changes.13 In the brain, the levels of the cortisol receptor are reduced, particularly in the hippocampus, which indirectly modulates the neurons in the hypothalamus that secrete CRH. We will explore the effects of maternal stress on the cortisol receptors.

Mothering: Beyond the Womb

Much of the research on the “programming” of the stress response has been conducted on mice and rats. These rodents are born at an earlier developmental stage than guinea pigs and humans, before the “rheostat” for the stress axis is set. This makes them more amenable to certain kinds of manipulation, the results of which can be readily monitored.

Long ago it was observed that when baby rats are removed from their mother’s nest for lengthy periods, they become stressed out for life. If, on the other hand, they are regularly removed for brief periods and handled carefully by humans, their stress response is actually reduced relative to unhandled siblings. In part, this is due to the mothers’ response after these separations. It turns out that after a brief removal, the mother licks the returned pup with a vengeance, whereas after a long separation the pup is treated more like a stranger and is lick deprived. The tactile stimulation provided by the lick grooming has a dampening effect on the stress response that is lifelong. Subsequently, it was discovered that there is natural variation in the amount of licking a mother allots to her pups; some mothers are much better lickers than others. Pups mothered by good or generous lickers show a dampened stress response relative to pups mothered by poor or stingy lickers.14 Moreover, if you take a baby mouse from a poor-licking mother and place it in a litter of a good licker, its stress response more closely resembles that of its foster mother than of its biological mother.15 This is the background for the following experiments. Much of this research was conducted by Michael Meaney and his collaborators at McGill University.

Meaney found that adult offspring of good lickers have more glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in certain parts of the brain—especially the hippocampus—than the offspring of poor lickers.16 This results in greater negative feedback sensitivity to cortisol and hence reduced levels of CRH. The reduced CRH levels result in a dampened stress-axis response to stressors relative to the offspring of poor lickers. Since these differences occur in adult offspring, they must result from long-term changes in gene regulation, above and beyond any short-term changes in gene regulation by cortisol of its target genes.

When the offspring of good lickers and poor lickers are cross-fostered as described above, the effects are reversed: the biological offspring of poor lickers raised by good lickers resemble the biological offspring of good lickers in all respects, including the number of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus.17 The reverse is also true. The cross-fostering experiments provide compelling evidence of a direct relationship between maternal care and the stress response, as manifest in GR levels, of adults.

What causes these long-term changes in the GR level? One obvious possibility is a long-term change in the cortisol receptor gene itself. To see how that might occur, we need to look upstream to factors that influence the expression of GR.* On the control panel of GR is a binding site for a transcription factor called NGFI-A (nerve growth factor inducible factor A). (For convenience we will reduce this unwieldy acronym for an even more unwieldy term to just NGF.)

When NGF binds to GR, it has an activating effect, increasing GR transcription. NGF levels are higher in pups mothered by good lickers than in pups of poor lickers.18 There are no such differences in NGF expression in adult mice, however. So the early, transient difference in NGF expression must permanently alter the responsiveness of the cortisol receptor gene in the brain. This occurs by means of an epigenetic alteration of the GR gene.

Epigenetic Gene Regulation

There are a number of epigenetic gene regulation mechanisms. One of the most pervasive and well studied is called methylation, which occurs when a methyl group (three hydrogen atoms attached to a carbon atom, or CH3) attaches to DNA.19 The effect of methylation is to inhibit the expression of the gene to which it is attached. Unlike testosterone, cortisol, and the other transcription factors we have discussed, methylation is not transient; the methyl group tends to stay attached to the DNA, even after it replicates during cell division. The methylated DNA not only persists throughout the life of the cell but is transmitted to all of the cells that descended from the cell in which the original epigenetic change occurred. As such, those genes that are epigenetically turned off as a result of methylation tend to stay turned off in that cell lineage.

But at certain critical periods in early development, things are in flux methylation-wise. Some biochemical pathways promote methylation, and other biochemical pathways prevent methylation or even cause demethylation. In mice the quality of mothering, as manifest in licking, tilts things toward one biochemical pathway or another for the GR gene. Good mothering promotes the demethylation pathway, while bad mothering leads to methylation. When GR is methylated, the transcription factor NGF does not bind well; as a result, fewer GR proteins are produced in the hippocampus and the stress axis becomes hyperactive, predisposing the mouse to fearfulness and anxiety.

Given the nature of epigenetic regulation, the earlier methylation occurs during development, the more pronounced and pervasive the effects. But methylation and other epigenetic processes continue long after birth—indeed, throughout the lifespan. Epigenetic alterations, some of them occurring long after birth, are thought to account for many differences in identical twins with respect to their stress response. Twins, especially twins reared apart, often differ markedly in their stress response, as manifest in anxiety, depression, and PTSD.20 Even twins reared together have increasingly divergent experiences as they age. To the extent that this divergence causes epigenetic differences, we would expect to find physiological and behavioral differences in the twins. If, for example, Steven had an identical brother, Stan, who stayed home to work at the steel mill, Steven would be more likely to have had an elevated stress response than Stan upon his return. Moreover, Steven would be more likely to have an elevated stress response ten years later.

Epigenetics and The Deer Hunter

The saga of Michael, Steven, and Nick, as dramatically depicted in The Deer Hunter, is a microcosm of the human reaction to extreme stress and some of the pathologies in the stress response that often result. All of these stress-related problems are caused by changes in gene regulation, which are long-term, sometimes lifelong. Such long-term changes in gene regulation are epigenetic. Here we explored one type of epigenetic process, called methylation, and one particular gene, which, when methylated, can result in a lifelong elevation of the stress response in mice. Scientists refer to results such as those from the mouse studies discussed here as a proof of concept. That does not mean that we can straightforwardly extrapolate from the mouse studies to the conditions of Michael, Steven, and Nick, or for that matter to any nonfictional human. That would be rash. For example, there are potentially a number of other genes, the disregulation of which could play an important role in a hyperactive stress response. And methylation, as we shall see, is but one type of epigenetic process. The mouse studies do suggest that research into epigenetic regulation will be a fruitful avenue on our way to understanding stress-related pathologies and ultimately to treating them.