Chapter 5

Getting Your Numbers, Times, and Measurements Straight

In This Chapter

Counting to 100 and beyond

Counting to 100 and beyond

Knowing times and periods of the day

Knowing times and periods of the day

Discovering calendar words and Chinese holidays

Discovering calendar words and Chinese holidays

Know how they figured out that China has more than a billion people? They counted, silly. Okay, they probably conducted an official census, but if you can learn your ABCs in English, you can at least learn to count to a hundred in Chinese. Just multiply that by ten, and you’ll get to a billion. The words for Chinese numbers are really quite logical — easier than you think — and they’re the cornerstone of this chapter.

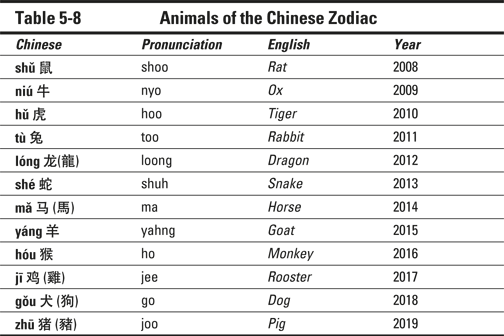

After you know how to count, you can also say the days of the week and the months of the year. The chapter also covers cardinal and ordinal numbers, so you can tell which came first (the chicken or the egg). If you’ve got a train to catch, you can look to this chapter to figure out how to tell time so you won’t be late. You can even tell your Chinese date what the date is in Chinese. Finally, I give you the lowdown on key Chinese holidays so you can plan your work and travel schedule accordingly, including showing you how to extend New Year’s greetings and providing a whole list of which animals are coming up in the Chinese zodiac. What more could you ask for?

Counting in Chinese

Figuring out things like how to specify the number of pounds of meat you want to buy at the market, how much money you want to change at the airport, or how much that cab ride from your hotel is really going to cost can be quite an ordeal if you don’t know the basic words for numbers. The following sections break down the Chinese counting rules and terms.

Numbers from 1 to 10

Learning to count from 1 to 10 in Chinese is as easy as yī 一 (ee) (one), èr 二 (are) (two), sān 三 (sahn) (three). Table 5-1 lists numbers from 1 to 10. People in China use Arabic numerals as well, though, so you can just as easily write 1, 2, 3, and everyone will know what you mean.

Table 5-1 Numbers from 1 to 10

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

líng 零 |

leeng |

0 |

|

yī 一 |

ee |

1 |

|

èr 二 |

are |

2 |

|

sān 三 |

sahn |

3 |

|

sì 四 |

suh |

4 |

|

wǔ 五 |

woo |

5 |

|

liù 六 |

lyo |

6 |

|

qī 七 |

chee |

7 |

|

bā 八 |

bah |

8 |

|

jiǔ 九 |

jyoe |

9 |

|

shí 十 |

shir |

10 |

Numbers from 11 to 99

After the number 10, you create numbers by saying the word 10 followed by the single digit that, when added to it, will combine to create numbers 11 through 19. It’s really easy. For example, 11 is shíyī 十一 (shir-ee) — literally, 10 plus 1. Same thing goes for 12, and so on through 19. Table 5-2 lists numbers from 11 to 19.

Table 5-2 Numbers from 11 to 19

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

shíyī 十一 |

shir-ee |

11 (Literally: 10 + 1) |

|

shí’èr 十二 |

shir-are |

12 (Literally: 10 + 2) |

|

shísān 十三 |

shir-sahn |

13 |

|

shísì 十四 |

shir-suh |

14 |

|

shíwǔ 十五 |

shir-woo |

15 |

|

shíliù 十六 |

shir-lyo |

16 |

|

shíqī 十七 |

shir chee |

17 |

|

shíbā 十八 |

shir-bah |

18 |

|

shíjiǔ 十九 |

shir-jyoe |

19 |

When you get to 20, you have to literally think two 10s — plus whatever single digit you want to add to that for 21 through 29, as shown in Table 5-3.

Table 5-3 Numbers from 20 to 29

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

èrshí 二十 |

are-shir |

20 (Literally: two 10s) |

|

èrshíyī 二十一 |

are-shir-ee |

21 (Literally: two 10s + 1) |

|

èrshí’èr 二十二 |

are-shir-are |

22 |

|

èrshísān 二十三 |

are-shir-sahn |

23 |

|

èrshísì 二十四 |

are-shir-suh |

24 |

|

èrshíwǔ 二十五 |

are-shir-woo |

25 |

|

èrshíliù 二十六 |

are-shir-lyo |

26 |

|

èrshíqī 二十七 |

are-shir-chee |

27 |

|

èrshíbā 二十八 |

are-shir-bah |

28 |

|

èrshíjiǔ 二十九 |

are-shir-jyoe |

29 |

The same basic idea goes for sānshí 三十 (sahn-shir) (30 [Literally: three 10s]), sìshí 四十 (suh-shir) (40), wǔshí 五十 (woo-shir) (50), liùshí 六十 (lyo-shir) (60), qīshí 七十 (chee-shir) (70), bāshí 八十 (bah-shir) (80), and jiǔshí 九十 (jyoe-shir) (90). What could be easier?

Numbers from 100 to 9,999

After the number 99, you can no longer count by tens. Here’s how you say 100 and 1,000:

100 is yìbǎi 一百 (ee-bye).

100 is yìbǎi 一百 (ee-bye).

1,000 is yìqiān 一千 (ee-chyan).

1,000 is yìqiān 一千 (ee-chyan).

Chinese people count all the way up to wàn 万 (萬) (wahn) (10,000) and then repeat in those larger amounts up to yì 亿 (億) (ee) (100 million).

Numbers from 10,000 to 100,000 and beyond

Here are the big numbers:

10,000 is yíwàn 一万 (一萬) (ee-wahn) (Literally: one unit of 10,000).

10,000 is yíwàn 一万 (一萬) (ee-wahn) (Literally: one unit of 10,000).

100,000 is shí wàn 十万 (十萬) (shir wahn) (Literally: ten units of 10,000).

100,000 is shí wàn 十万 (十萬) (shir wahn) (Literally: ten units of 10,000).

1 million is yìbǎi wàn 一百万 (一百萬) (ee-bye wahn) (Literally: 100 units of 10,000).

1 million is yìbǎi wàn 一百万 (一百萬) (ee-bye wahn) (Literally: 100 units of 10,000).

100 million is yí yì 一亿 (一億) (ee ee).

100 million is yí yì 一亿 (一億) (ee ee).

How ’bout those halves?

So what happens if you want to add a half to anything? Well, the word for half is bàn 半 (bahn), and it can either come at the beginning, such as in bàn bēi kělè (半杯可乐) (半杯可樂) (bahn bay kuh-luh) (a half a glass of cola), or after a number and classifier but before the object to mean and a half, such as in yí ge bàn xīngqī 一个半星期 (一個半星期) (ee guh bahn sheeng-chee) (a week and a half).

Ordinal numbers

If you want to indicate the order of something, add the word dì 第 (dee) before the numeral:

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

dì yī 第一 |

dee ee |

first |

|

dì èr 第二 |

dee are |

second |

|

dì sān 第三 |

dee sahn |

third |

|

dì sì 第四 |

dee suh |

fourth |

|

dì wǔ 第五 |

dee woo |

fifth |

|

dì liù 第六 |

dee lyo |

sixth |

|

dì qī 第七 |

dee chee |

seventh |

|

dì bā 第八 |

dee bah |

eighth |

|

dì jiǔ 第九 |

dee jyoe |

ninth |

|

dì shí 第十 |

dee shir |

tenth |

If a noun follows the ordinal number, a classifier needs to go between them, such as in dì bā ge xuéshēng 第八个学生 (第八個學生) (dee bah guh shweh-shuhng) (the eighth student) or dì yī ge háizi 第一个孩子 (第一個孩子) (dee ee guy hi-dzuh) (the first child).

Asking how many or how much

You have two ways to ask how much something is or how many of something there are. The first is the question word duōshǎo 多少 (dwaw-shaow), which you use when referring to something for which the answer is probably more than ten. The second is jǐ 几(幾) (jee) or jǐge几个 (幾個) (jee-guh), which you use when referring to something for which the answer is probably going to be less than ten:

Nàge qìchē duōshǎo qián? 那个汽车多少钱? (那個汽車多少錢?) (nah-guh chee-chuh dwaw-shaow chyan?) (How much is that car?)

Nǐ xiǎo nǚ’ér jīnnián jǐ suì? 你小女儿今年几岁? (你小女兒今年幾歲?) (nee shyaow nyew-are jin-nyan jee sway?) (How old is your little girl this year?)

Telling Time

All you have to do to find out the shíjiān 时间 (時間) (shir-jyan) (time) is take a peek at your shǒubiǎo 手表 (show-byaow) (watch) or look at the zhōng 钟 (鐘) (joong) (clock) on the wall. These days, even your computer or cellphone shows the time. And you can always revert to that beloved luòdìshì dà bǎizhōng 落地式大摆钟 (落地式大擺鐘) (lwaw-dee-shir dah bye-joong) (grandfather clock) in your parents’ living room. You no longer have any excuse to chídào 迟到 (遲到) (chir-daow) (be late), especially if you own a nào zhōng 闹钟 (鬧鐘) (now-joong) (alarm clock)!

Asking and stating the time

Want to know what time it is? Just walk up to someone and say Xiànzài jǐdiǎn zhōng? 现在几点钟? (現在幾點鐘?) (shyan-dzye jee-dyan joong?). It almost literally translates into Now how many hours are on the clock? In fact, you can even leave off the word clock and still ask for the time: Xiànzài jǐdiǎn? 现在几点? (現在幾點?) (shyan-dzye jee-dyan?). Isn’t that easy?

To understand the answers to those questions, though, you need to understand how to tell time in Chinese. You can express time in Chinese by using the words diǎn 点 (點) (dyan) (hour) and fēn 分 (fun) (minute). Isn’t using fēn fun? You can even talk about time in miǎo 秒 (meow) (seconds) if you like and sound like a cat. Table 5-4 shows you how to pronounce all the hours on the clock.

Table 5-4 Telling Time in Chinese

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

yī diăn zhōng 一点钟 (一點鐘) |

ee-dyan joong |

1:00 |

|

liǎng diǎn zhōng 两点钟 (兩點鐘) |

lyahng-dyan joong |

2:00 |

|

sān diǎn zhōng 三点钟 (三點鐘) |

sahn-dyan joong |

3:00 |

|

sì diăn zhōng 四点钟 (四點鐘) |

suh-dyan joong |

4:00 |

|

wǔ diǎn zhōng 五点钟 (五點鐘) |

woo-dyan joong |

5:00 |

|

liù diǎn zhōng 六点钟 (六點鐘) |

lyo-dyan joong |

6:00 |

|

qī diǎn zhōng 七点钟 (七點鐘) |

chee-dyan joong |

7:00 |

|

bā diǎn zhōng 八点钟 (八點鐘) |

bah-dyan joong |

8:00 |

|

jiǔ diǎn zhōng 九点钟 (九點鐘) |

jyo-dyan joong |

9:00 |

|

shí diăn zhōng 十点钟 (十點鐘) |

shir-dyan joong |

10:00 |

|

shíyī diǎn zhōng 十一 点钟 (十一點鐘) |

shir-ee-dyan joong |

11:00 |

|

zhōngwǔ 中午 |

joong-woo |

noon |

|

bànyè 半夜 |

bahn-yeh |

midnight |

Specifying the time of the day

The Chinese are very precise when they tell time. You can’t just say sān diǎn zhōng 三点钟 (三點鐘) (sahn dyan joong) when you want to say 3:00. Do you mean to say qīngzǎo sān diǎn zhōng 清早三点钟 (清早三點鐘) (cheeng-dzaow sahn dyan joong) (3:00 a.m.) or xiàwǔ sāndiǎn zhōng 下午三点钟 (下午三點鐘) (shyah-woo sahn-dyan joong) (3:00 p.m.)? Another wrinkle: Noon and midnight aren’t the only dividers the Chinese use to split up the day.

Here’s a list of the major segments of the day:

qīngzǎo 清早 (cheeng-dzaow): the period from midnight to 6:00 a.m.

qīngzǎo 清早 (cheeng-dzaow): the period from midnight to 6:00 a.m.

zǎoshàng 早上 (dzaow-shahng): the period from 6:00 a.m. to noon

zǎoshàng 早上 (dzaow-shahng): the period from 6:00 a.m. to noon

xiàwǔ 下午 (shyah-woo): the period from noon to 6:00 p.m.

xiàwǔ 下午 (shyah-woo): the period from noon to 6:00 p.m.

wǎnshàng 晚上 (wahn-shahng): the period from 6:00 p.m. to midnight

wǎnshàng 晚上 (wahn-shahng): the period from 6:00 p.m. to midnight

The segment of the day that you refer to needs to come before the actual time itself in Chinese. Here are some samples of combining the segment of the day with the time of day:

qīngzǎo yì diǎn yí kè 清早一点一刻 (清早一點一刻) (cheeng-dzaow ee dyan ee kuh) (1:15 a.m.)

wǎnshàng qī diǎn zhōng 晚上七点钟 (晚上七點鐘) (wahn-shahng chee dyan joong) (7:00 p.m.)

xiàwǔ sān diǎn bàn 下午三点半 (下午三點半) (shyah-woo sahn dyan bahn) (3:30 p.m.)

zǎoshàng bā diǎn èrshíwǔ fēn 早上八点二十五分 (dzaow-shahng bah dyan are-shir-woo fun) (8:25 a.m.)

If you want to indicate half an hour, just add bàn (bahn) (half) after the hour:

sān diǎn bàn 三点半 (三點半) (sahn-dyan bahn) (3:30)

shíyī diǎn bàn 十一点半 (十一點半) (shir-ee-dyan bahn) (11:30)

sì diǎn bàn 四点半 (四點半) (suh-dyan bahn) (4:30)

Do you want to indicate a quarter of an hour or three quarters of an hour? Just use the phrases yí kè 一刻 (ee kuh) and sān kè三刻 (sahn kuh), respectively, after the hour:

liǎng diǎn yí kè 两点一刻 (兩點一刻) (lyahng-dyan ee kuh) (2:15)

qī diǎn sān kè 七点三刻 (七點三刻) (chee-dyan sahn kuh) (7:45)

sì diǎn yí kè 四点一刻 (四點一刻) (suh-dyan ee kuh) (4:15)

wǔ diǎn sān kè 五点三刻 (五點三刻) (woo-dyan sahn kuh) (5:45)

When talking about time, you may prefer to indicate a certain number of minutes before or after a particular hour. To do so, you use either yǐqián 以前 (ee-chyan) (before) or yǐhòu 以后(以後) (ee-ho) (after) along with the time (though you can also use it with days and months, concepts that I cover later in the chapter). Here are a couple of examples:

qīngzǎo 4-diǎn bàn yǐhòu 清早四点半以后 (清早四點半以後) (cheeng-dzaow suh-dyan bahn ee-ho) (after 4:30 a.m.)

xiàwǔ 3-diǎn zhōng yǐqián 下午三点钟以前 (下午三點鐘以前) (shyah-woo sahn-dyan joong ee-chyan) (before 3 p.m.)

Here are some other examples of alternative ways to indicate the time:

chà shí fēn wǔ diǎn 差十分五点 (差十分五點) (chah shir fun woo dyan) (10 minutes to 5:00)

wǔ diǎn chà shí fēn 五点差十分 (五點差十分) (woo dyan chah shir fun) (10 minutes to 5:00)

sì diǎn wǔshí fēn 四点五十分 (四點五十分) (suh dyan woo-shir fun) (4:50)

chà yí kè qī diǎn 差一刻七点 (差一刻七點) (chah ee kuh chee dyan) (a quarter to 7:00)

qī diǎn chà yí kè 七点差一刻 (七點差一刻) (chee dyan chah ee kuh) (a quarter to 7:00)

liù diǎn sān kè 六点三刻 (六點三刻) (lyo dyan sahn kuh) (6:45)

liù diǎn sìshíwǔ fēn 六点四十五分 (六點四時五分) (lyo dyan suh-shir-woo fun) (6:45)

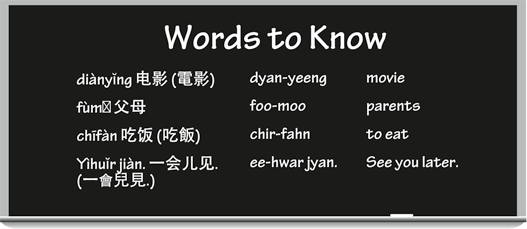

Talkin’ the Talk

Xiǎo Huá:

Wǒmen jīntiān wǎnshàng qù kàn diànyǐng hǎo bùhǎo?

waw-men jin-tyan wahn-shahng chyew kahn dyan-yeeng how boo-how?

Let’s go see a movie tonight, okay?

Chén Míng:

Bùxíng. Wǒde fùmǔ jīntiān wǎnshàng yídìng yào wǒ gēn tāmen yìqǐ chī wǎnfàn.

boo-sheeng. waw-duh foo-moo jin-tyan wahn-shahng ee-deeng yaow waw gun tah-men ee-chee chir wahn-fahn.

No can do. My parents are adamant that I have dinner with them tonight.

Xiǎo Huá:

Nǐmen jǐdiǎn zhōng chīfàn?

nee-men jee-dyan joong chir-fahn?

What time do you eat?

Chén Míng:

Píngcháng wǒmen liùdiǎn zhōng zuǒyòu chīfàn.

peeng-chahng waw-men lyo-dyan joong dzwaw yo chir-fahn.

We usually eat around 6:00.

Xiǎo Huá:

Hǎo ba. Nǐ chīfàn yǐhòu wǒmen qù kàn yíbù jiǔdiǎn zhōng yǐqián de piānzi, hǎo bùhǎo?

how-bah. nee chir-fahn ee-ho waw-men chyew kahn ee-boo jyo-dyan joong ee-chyan duh pyan-dzuh, how boo-how?

Okay. How about we see a movie that starts before 9:00 after you’re finished eating?

Chén Míng:

Hěn hǎo. Yìhuǐr jiàn.

hun how. ee-hwar jyan.

Okay. See you later.

Save the Date: Using the Calendar and Stating Dates

So what day is jīntiān 今天 (jin-tyan) (today)? Could it be xīngqīliù 星期六 (sheeng-chee-lyo) (Saturday), when you can sleep late and go see a movie in the evening with friends? Or is it xīngqīyī 星期一 (sheeng-chee-ee) (Monday), when you have to be at work by 9:00 a.m. to prepare for a 10:00 a.m. meeting? Or maybe it’s xīngqīwǔ 星期五 (sheeng-chee-woo) (Friday), and you already have two tickets for the symphony that begins at 8:00 p.m. In the following sections, I give you the words you need to talk about days and months and put them together into specific dates. I also give you the lowdown on some major Chinese holidays.

Dealing with days of the week

You may not be a big fan of going to work Monday to Friday, but when the zhōumò 周末 (週末) (joe-maw) (weekend) comes, you have two days of freedom and fun. Before you know it, though, Monday comes again. Chinese people recognize seven days in the week just as Americans do, and the Chinese week begins on Monday and ends on xīngqītiān 星期天 (sheeng-chee-tyan) (Sunday). Table 5-5 spells out the days of the week.

Table 5-5 Days of the Week

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

xīngqīyī 星期一 |

sheeng-chee-ee |

Monday |

|

xīngqī’èr 星期二 |

sheeng-chee-are |

Tuesday |

|

xīngqīsān 星期三 |

sheeng-chee-sahn |

Wednesday |

|

xīngqīsì 星期四 |

sheeng-chee-suh |

Thursday |

|

xīngqīwǔ 星期五 |

sheeng-chee-woo |

Friday |

|

xīngqīliù 星期六 |

sheeng-chee-lyo |

Saturday |

|

xīngqītiān 星期天 |

sheeng-chee-tyan |

Sunday |

If you’re talking about zhèige xīngqī 这个星期 (這個星期) (jay-guh sheeng-chee) (this week) in Chinese, you’re talking about any time between this past Monday through this coming Sunday. Anything earlier is considered shàngge xīngqī 上个星期 (上個星期) (shahng-guh sheeng-chee) (last week). Any day after this coming Sunday is automatically part of xiàge xīngqī 下个星期 (下個星期) (shyah-guh sheeng-chee) (next week) at the earliest. Here a few more week-related terms:

hòutiān 后天 (後天) (ho-tyan) (the day after tomorrow)

hòutiān 后天 (後天) (ho-tyan) (the day after tomorrow)

míngtiān 明天 (meeng-tyan) (tomorrow)

míngtiān 明天 (meeng-tyan) (tomorrow)

qiántiān 前天 (chyan-tyan) (the day before yesterday)

qiántiān 前天 (chyan-tyan) (the day before yesterday)

zuótiān 昨天 (dzwaw-tyan) (yesterday)

zuótiān 昨天 (dzwaw-tyan) (yesterday)

So jīntiān xīngqījǐ? 今天星期几? (今天星期幾?) (jin-tyan sheeng-chee-jee) (What day is it today?) Where does today fit in your weekly routine?

Jīntiān xīngqī’èr. 今天星期二. (jin-tyan sheeng-chee-are.) (Today is Tuesday.)

Jīntiān xīngqī’èr. 今天星期二. (jin-tyan sheeng-chee-are.) (Today is Tuesday.)

Wǒmen měige xīngqīyī kāihuì. 我们每个星期一开会. (我們每個星期一開會.) (waw-men may-guh sheeng-chee-ee kye-hway.) (We have meetings every Monday.)

Wǒmen měige xīngqīyī kāihuì. 我们每个星期一开会. (我們每個星期一開會.) (waw-men may-guh sheeng-chee-ee kye-hway.) (We have meetings every Monday.)

Wǒ xīngqīyī dào xīngqīwǔ gōngzuò. 我星期一到星期五工作. (waw sheeng-chee-ee daow sheeng-chee-woo goong-dzwaw.) (I work from Monday to Friday.)

Wǒ xīngqīyī dào xīngqīwǔ gōngzuò. 我星期一到星期五工作. (waw sheeng-chee-ee daow sheeng-chee-woo goong-dzwaw.) (I work from Monday to Friday.)

Xiàge xīngqīsān shì wǒde shēngrì. 下个星期三是我的生日. (下個星期三是我的生日.) (shyah-guh sheeng-chee-sahn shir waw-duh shung-ir.) (Next Wednesday is my birthday.)

Xiàge xīngqīsān shì wǒde shēngrì. 下个星期三是我的生日. (下個星期三是我的生日.) (shyah-guh sheeng-chee-sahn shir waw-duh shung-ir.) (Next Wednesday is my birthday.)

Naming the months

When you know how to count from 1 to 12 (refer to the earlier section “Counting in Chinese”), naming the months in Chinese is really easy. Just think of the cardinal number for each month and put that in front of the word yuè 月 (yweh) (month). For example, January is yīyuè 一月 (ee-yweh), February is 二月 èryuè (are-yweh) and so on. I list the months of the year in Table 5-6. Which month is your shēngrì 生日 (shung-ir) (birthday)?

Table 5-6 Months of the Year and Other Pertinent Terms

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

yīyuè 一月 |

ee-yweh |

January |

|

èryuè 二月 |

are-yweh |

February |

|

sānyuè 三月 |

sahn-yweh |

March |

|

sìyuè 四月 |

suh-yweh |

April |

|

wǔyuè 五月 |

woo-yweh |

May |

|

liùyuè 六月 |

lyo-yweh |

June |

|

qīyuè 七月 |

chee-yweh |

July |

|

bāyuè 八月 |

bah-yweh |

August |

|

jiǔyuè 九月 |

jyo-yweh |

September |

|

shíyuè 十月 |

shir-yweh |

October |

|

shíyīyuè 十一月 |

shir-ee-yweh |

November |

|

shí’èryuè 十二月 |

shir-are-yweh |

December |

|

shàngge yuè 上个月 (上個月) |

shahng-guh-yweh |

last month |

|

xiàge yuè 下个月 (下個月) |

shyah-guh-yweh |

next month |

|

zhèige yuè 这个月 (這個月) |

jay-guh-yweh |

this month |

Shí’èryuè, yīyuè, and èryuè together make up one of the sì jì 四季 (suh-jee) (four seasons); check it out with the others in Table 5-7.

Table 5-7 The Four Seasons

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

dōngjì 冬季 |

doong-jee |

winter |

|

chūnjì 春季 |

chwun-jee |

spring |

|

xiàjì 夏季 |

shyah-jee |

summer |

|

qiūjì 秋季 |

chyo-jee |

fall |

Specifying dates

To ask what today’s date is, you simply say Jīntiān jǐyuè jǐhào? 今天几月几号? (今天幾月幾號?) (jin-tyan jee-yweh jee-how?) (Literally: Today is what month and what day?) To answer that question, remember that the larger unit of the month always comes before the smaller unit of the date in Chinese:

sānyuè sì hào 三月四号 (三月四號) (sahn-yweh suh how) (March 4)

shí’èryuè sānshí hào 十二月三十号 (十二月三十號) (shir-are-yweh sahn-shir how) (December 30)

yīyuè èr hào 一月二号 (一月二號) (ee-yweh are how) (January 2)

Days don’t exist in a vacuum — or even just in a week — and four whole weeks make up one whole month. So if you want to be more specific, you have to say the month before the day, followed by the day of the week:

liùyuè yī hào, xīngqīyī 六月一号星期一 (六月一號星期一) (lyo-yweh ee how, sheeng-chee ee) (Monday, June 1)

sìyuè èr hào, xīngqītiān 四月二号星期天 (四月二號星期天 (suh-yweh are how, sheeng-chee-tyan) (Sunday, April 2)

The same basic idea goes for saying the days of the week. All you have to do is add the number of the day of the week (Monday: Day 1), preceded by the word lǐbài 礼拜 (禮拜) (lee-bye) or xīngqī 星期 (sheeng-chee), meaning week, to say the day you mean. For example, Monday is xīngqī yī 星期一 (sheeng chee ee) or lǐbài yī 礼拜一 (禮拜一), Tuesday is xīngqī èr 星期二 (sheeng chee are) or lǐbài èr 礼拜二 (禮拜二), and so on. The only exception is Sunday, when you have to add the word tiān 天 (tyan) (heaven, day) in place of a number. Wǒde tiān! 我的天! (waw-duh tyan!) (My heavens!) Isn’t this easy?

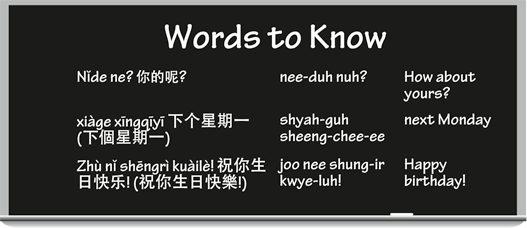

Talkin’ the Talk

Joseph asks Julia about her birthday.

Joseph:

Julia, nǐde shēngrì shì jǐyuè jǐhào?

Julia, nee-duh shung-ir shir jee-yweh jee-how?

Julia, when’s your birthday?

Julia:

Wǒde shēngrì shì liùyuè èr hào. Nǐde ne?

waw-duh shung-ir shir lyo-yweh are how. nee-duh nuh?

My birthday is June2. How about yours?

Joseph:

Wǒde shēngrì shì wǔyuè qī hào.

waw-duh shung-ir shir woo-yweh chee how.

My birthday is May7.

Julia:

Nèmme, xiàge xīngqīyī jiù shì nǐde shēngrì! Zhù nǐ chàjǐtiān shēngrì kuàilè!

nummuh, shyah-guh sheeng-chee-ee jyo shir nee-duh shung-ir! joo nee chah-jee-tyan shung-ir kwye-luh!

In that case, next Monday is your birthday! Happy almost birthday!

Celebrating Chinese holidays

When was the last time you saw a wǔshī 舞狮 (舞獅) (woo-shir) (lion dance) in Chinatown? You can catch this colorful (and noisy) dance and all the other festivities during nónglì xīn nián 农历新年 (農曆新年) (noong-lee sheen nyan) (the Lunar New Year), also known as chūnjié 春節 (chwun-jyeh) (the Spring Festival). Just be careful not to get too close to all the yān huǒ 烟火 (焰火) (yan hwaw) (fireworks).

To extend New Year’s greetings, you can say Xīn nián kuàilè! 新年快乐! (新年快樂!) (shin nyan kwye-luh!) (Happy New Year!) or, better yet, Gōngxī fācái! 恭喜发财! (恭喜發財!) (goong-she fah-tsye!) (Congratulations, and may you prosper!). In fact, you can start saying this on chúxī 除夕 (choo-shee) (Chinese New Year’s Eve), the night when Chinese families get together to share a big, traditional dinner. The next morning children wish their parents a happy New Year and get hóng bāo 红包 (紅包) (hoong baow) (red envelopes) with money in them. What a great way to start the year!

Yuán xiāo jié 元宵节 (元宵節) (ywan shyaow jyeh) (Lantern Festival): Lantern parades and lion dances help celebrate the first full moon, which marks the end of the Chinese New Year, in either January or February.

Yuán xiāo jié 元宵节 (元宵節) (ywan shyaow jyeh) (Lantern Festival): Lantern parades and lion dances help celebrate the first full moon, which marks the end of the Chinese New Year, in either January or February.

Qīngmíng jié 清明节 (清明節) (cheeng-meeng jyeh) (Literally: the Clear and Bright Festival): This celebration at the beginning of April is actually Tomb Sweeping Day, when families go on spring outings to clean and make offerings at the graves of their ancestors.

Qīngmíng jié 清明节 (清明節) (cheeng-meeng jyeh) (Literally: the Clear and Bright Festival): This celebration at the beginning of April is actually Tomb Sweeping Day, when families go on spring outings to clean and make offerings at the graves of their ancestors.

Duānwǔ jié 端午节 (端午節) (dwan-woo jyeh) (Dragon Boat Festival): To commemorate the ancient poet Qū Yuán 屈原 (chew ywan), who drowned himself to protest government corruption, Chinese people eat zòngzǐ 粽子(dzoong-dzuh) (glutinous rice dumplings wrapped in lotus leaves), drink yellow rice wine, and hold dragon boat races on the river. This holiday often falls in late May or early June.

Duānwǔ jié 端午节 (端午節) (dwan-woo jyeh) (Dragon Boat Festival): To commemorate the ancient poet Qū Yuán 屈原 (chew ywan), who drowned himself to protest government corruption, Chinese people eat zòngzǐ 粽子(dzoong-dzuh) (glutinous rice dumplings wrapped in lotus leaves), drink yellow rice wine, and hold dragon boat races on the river. This holiday often falls in late May or early June.

Zhōngqiū jié 中秋节 (中秋節) (joong-chyo jyeh) (Mid-Autumn Festival): This popular lunar harvest festival celebrates Cháng’é 嫦娥 (chahng-uh), the Chinese goddess of the moon (and of immortality). Red bean and lotus seed pastries called mooncakes are eaten, romantic matches are made, and all’s right with the world. This holiday usually comes in September.

Zhōngqiū jié 中秋节 (中秋節) (joong-chyo jyeh) (Mid-Autumn Festival): This popular lunar harvest festival celebrates Cháng’é 嫦娥 (chahng-uh), the Chinese goddess of the moon (and of immortality). Red bean and lotus seed pastries called mooncakes are eaten, romantic matches are made, and all’s right with the world. This holiday usually comes in September.

Sizing Up Weights and Measures

The metric system is standard in both mainland China and Taiwan. The basic unit of weight is the gōngkè 公克 (goong-kuh) (gram), so you usually buy fruits and vegetables in multiples of that measure. The standard liquid measurement is the shēng 升 (shung) (liter). One liter equals about 1.06 quarts. Table 5-9 gives you a list of weights and measures.

Table 5-9 Weights and Measures

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

Volume |

||

|

àngsi 盎司 |

ahng-suh |

ounce |

|

jiālún 加仑 (加侖) |

jyah-lwun |

gallon |

|

kuātuō 夸脱 (夸脫) |

kwah-twaw |

quart |

|

pǐntuō 品脱 (品脫) |

peen-twaw |

pint |

|

shēng 升 |

shung |

liter |

|

Weight/Mass |

||

|

bàng 镑 (鎊) |

bahng |

pound |

|

háokè 毫克 |

how-kuh |

milligram |

|

gōngkè 公克 |

goong-kuh |

gram |

|

jīn; gōngjīn 斤; 公斤 |

jeen; goong-jeen |

kilogram |

|

Distance |

||

|

gōnglǐ 公里 |

goong-lee |

kilometer |

|

límǐ 厘米 |

lee-mee |

centimeter |

|

mǎ 码 (碼) |

mah |

yard |

|

mǐ 米 |

mee |

meter |

|

yīngchǐ 英尺 |

eeng-chir |

foot |

|

yīngcùn 英寸 |

eeng-tswun |

inch |

|

yīnglǐ 英里 |

eeng-lee |

mile |

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

Count to 10 and then to 100 in multiples of 10 by filling in the blanks with the correct numbers. Turn to Appendix D for the answers.

yī 一

èr 二

sān 三

sì 四

______

liù 六

______

bā 八

jiǔ 九

______

èrshí 二十

______

sìshí 四十

wǔshí 五十

______

qīshí 七十

bāshí 八十

_____

yìbǎi 一百

If the number

If the number  In Chinese, numbers are represented with the higher units of value first. So the number

In Chinese, numbers are represented with the higher units of value first. So the number  Numbers play an interesting role in everyday speech in China. Sometimes you’ll hear someone say emphatically

Numbers play an interesting role in everyday speech in China. Sometimes you’ll hear someone say emphatically