Chapter 8

Dining Out and Shopping for Food

In This Chapter

Eating, Chinese style

Eating, Chinese style

Ordering and conversing in restaurants

Ordering and conversing in restaurants

Drinking up tea knowledge

Drinking up tea knowledge

Shopping for groceries

Shopping for groceries

You may think you already know what Chinese food is all about, but if you suddenly find yourself a guest in a Chinese friend’s home or the guest of honor at a banquet for your company’s new branch in Shanghai, you may want to keep reading. This chapter not only helps you communicate when you’re hungry or thirsty, go grocery shopping, and order food in a restaurant but also gives you some useful tips on how to be both a wonderful guest and a gracious host when you have only one shot at making a good impression.

Feeling hungry yet? Allow me to whet your appetite by inviting you to take a closer look at world-renowned Chinese cuisine. No doubt you’re already familiar with a great many Chinese dishes, from chow mein and chop suey to sweet and sour pork to that delicious favorite of all Chinese fare, dim sum.

Exploring Chinese food and Chinese eating etiquette is a great way to discover Chinese culture. You can also use what you discover in this chapter to impress your date by ordering in Chinese the next time you eat out.

All About Meals

If you feel hungry when beginning this section, you should stop to chī 吃 (chir) (eat) fàn 饭 (飯) (fahn) (food). In fact, fàn always comes up when you talk about meals in China. Different meals throughout the day, for example, are called

zǎofàn 早饭 (早飯) (dzaow-fahn) (breakfast)

zǎofàn 早饭 (早飯) (dzaow-fahn) (breakfast)

wǔfàn 午饭 (午飯) (woo-fahn) (lunch)

wǔfàn 午饭 (午飯) (woo-fahn) (lunch)

wǎnfàn 晚饭 (晚飯) (wahn-fahn) (dinner)

wǎnfàn 晚饭 (晚飯) (wahn-fahn) (dinner)

For centuries, Chinese people greeted each other not by saying Nǐ hǎo ma? 你好吗? (你好嗎?) (nee how ma?) (How are you?) but rather by saying Nǐ chīfàn le méiyǒu? 你吃饭了没有? (你 吃飯了沒有?) (nee chir-fahn luh mayo?) (Literally: “Have you eaten?”)

Satisfying your hunger

If you’re hungry, you can say Wǒ hěn è. 我很饿. (我很餓.) (waw hun uh.) (I’m very hungry.) and wait for a friend to invite you for a bite to eat. If you’re thirsty, just say Wǒde kǒu hěn kě. 我的口很渴. (waw-duh ko hun kuh.) (Literally: My mouth is very dry.) to hear offers for all sorts of drinks. You may not get a chance to even utter these words, however, because Chinese rules of hospitality dictate offering food and drink to guests right off the bat.

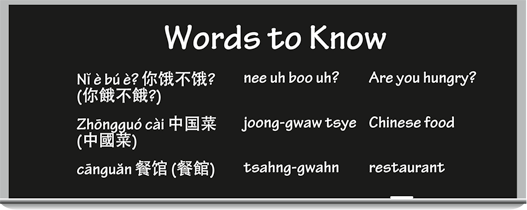

Nǐ è bú è? 你饿不饿? (你餓不餓?) (nee uh boo uh?) (Are you hungry?)

Nǐ è bú è? 你饿不饿? (你餓不餓?) (nee uh boo uh?) (Are you hungry?)

Nǐ è ma? 你饿吗? (你餓嗎?) (nee uh mah?) (Are you hungry?)

Nǐ è ma? 你饿吗? (你餓嗎?) (nee uh mah?) (Are you hungry?)

Nǐ hái méi chī wǎnfàn ba. 你还没吃晚饭吧. (你還沒吃晚飯吧.) (nee hi may chir wahn-fahn bah.) (I bet you haven’t had dinner yet.)

Nǐ hái méi chī wǎnfàn ba. 你还没吃晚饭吧. (你還沒吃晚飯吧.) (nee hi may chir wahn-fahn bah.) (I bet you haven’t had dinner yet.)

By checking to see whether the other person is hungry first, you display the prized Chinese sensibility of consideration for others, and you give yourself a chance to gracefully get out of announcing that you, in fact, are really the one who’s dying for some Chinese food. If you want, you can always come right out and say that you’re the one who’s hungry by substituting wǒ 我 (waw) (I) for nǐ 你 (nee) (you).

You can say something like Nǐ xiān hē jiǔ. 你先喝酒. (nee shyan huh jyoe.) (Drink wine first.), but you sound nicer and friendlier if you say Nǐ xiān hē jiǔ ba. 你先喝酒吧. (nee shyan huh jyoe bah.) (Better drink some wine first./Why not have some wine first?)

When an acquaintance invites you over for dinner, he may ask Nǐ yào chī fàn háishì yào chī miàn? 你要吃饭还是要吃面? (你要吃飯還是要吃麵?) (nee yaow chir fahn hi-shir yaow chir myan) (Do you want to eat rice or noodles?) Naturally, your host doesn’t just serve you a bowl of rice or noodles; he wants to know what basic staple to prepare before he adds the actual cài 菜 (tsye) (the various dishes that go with the rice or noodles).

Sitting down to eat and practicing proper table manners

After you’ve chosen what staple you want and it actually sits staring you in the face on the table, you probably want to know what utensils to use in order to eat the meal. Don’t be shy about asking for a good old fork and knife, even if you’re in a Chinese restaurant. The idea that Chinese people all eat with chopsticks is a myth anyway. Table 8-1 presents a handy list of utensils you need to know how to say at one point or another.

Table 8-1 Utensils

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

bēizi 杯子 |

bay-dzuh |

cup |

|

cānjīnzhǐ 餐巾纸 (餐巾紙) |

tsahn-jeen-jir |

napkin |

|

chāzi 叉子 |

chah-dzuh |

fork |

|

dāozi 刀子 |

daow-dzuh |

knife |

|

pánzi 盘子 (盤子) |

pahn-dzuh |

plate |

|

tiáogēng 调羹 (調羹) |

tyaow-gung |

spoon |

|

wǎn 碗 |

wahn |

bowl |

|

yì shuāng kuàizi 一双筷子 (一雙筷子) |

ee shwahng kwye-dzuh |

a pair of chopsticks |

When you receive an invitation to someone’s home, always remember to bring a small gift and to toast others before you take a drink yourself during the meal. The Chinese have no problem slurping their soup or belching during or after a meal, by the way, so don’t be surprised if you witness both at a perfectly formal gathering. And to remain polite and in good graces, you should always make an attempt to serve someone else before yourself when dining with others; otherwise, you run the risk of appearing rude and self-centered. (Check out Chapter 21 for a list of other etiquette considerations.)

Don’t hesitate to use some of these phrases at the table:

Duō chī yìdiǎr ba! 多吃一点儿吧! (多吃一點兒吧!) (dwaw chir ee-dyar bah!) (Have some more!)

Duō chī yìdiǎr ba! 多吃一点儿吧! (多吃一點兒吧!) (dwaw chir ee-dyar bah!) (Have some more!)

Gānbēi! 干杯! (幹杯!) (gahn-bay!) (Bottoms up!)

Gānbēi! 干杯! (幹杯!) (gahn-bay!) (Bottoms up!)

Màn chī or màn màn chī! 慢吃 or 慢慢吃! (mahn chir! or mahn mahn chir!) (Bon appetite!) This phrase literally means Eat slowly., but it’s loosely translated as Take your time and enjoy your food.

Màn chī or màn màn chī! 慢吃 or 慢慢吃! (mahn chir! or mahn mahn chir!) (Bon appetite!) This phrase literally means Eat slowly., but it’s loosely translated as Take your time and enjoy your food.

Wǒ chībǎo le. 我吃饱了. (我吃飽了.) (waw chir-baow luh.) (I’m full.)

Wǒ chībǎo le. 我吃饱了. (我吃飽了.) (waw chir-baow luh.) (I’m full.)

Zìjǐ lái. 自己来. (自己來.) (dzuh-jee lye.) (I’ll help myself.)

Zìjǐ lái. 自己来. (自己來.) (dzuh-jee lye.) (I’ll help myself.)

Getting to Know Chinese Cuisines

Northern Chinese food, found in places such as Beijing, is famous for all sorts of meat dishes. You find plenty of beef, lamb, and duck (remember Peking Duck?). Garlic and scallions garnish the meat for good measure; otherwise, though, Northern cooking is bland because of the lack of excessive condiments. So don’t expect anything overtly salty, sweet, or spicy.

Shanghai dining, as well as that of the neighboring Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces, represents Eastern cuisine. Because these places are close to the sea and boast many lakes, you can find an infinite variety of seafood in this part of China. Fresh vegetables, different kinds of bamboo, and plenty of soy sauce and sugar are also hallmarks of this region’s cuisine.

Food from Sichuan and Hunan provinces is considered Western Chinese cuisine. Western Chinese food is common in Chinese restaurants in the United States. Because this part of China is hot and humid, hot peppers and salt are commonly found here. (The food isn’t the only thing considered fiery in these parts; some famous revolutionaries, such as Mao Zedong, have hailed from this region of China.)

Southern Chinese cuisine comes from Guangdong (formerly known as Canton) province, as well as from Fujian and Taiwan. Like Shanghai cuisine, it offers plentiful amounts of seafood, fresh fruits, and vegetables. One of the most famous types of food from Guangdong that you’ve no doubt heard of is dim sum (deem sum), which in standard Mandarin is pronounced diǎn xīn 点心 (點心) (dyan sheen). You can read more about this fare in the later section “Dipping into some dim sum.”

Dining Out

Breaking bread with friends at home is great, but sometimes you want the Chinese dining experience out on the town. Taking on a menu in a foreign language can be daunting (and even that won’t help you find the restroom), so the following sections take you through all sorts of restaurant basics, from sorting through the food options (including checking out dim sum) to ordering, paying the bill, and yes, locating the facilities.

Flip to Table 8-1 earlier in the chapter for a list of common utensils. Here are a couple of additional items you commonly encounter or need to ask for when dining out:

yíge rè máojīn 一个热毛巾 (一個熱毛巾) (ee-guh ruh maow-jeen) (a hot towel)

yíge rè máojīn 一个热毛巾 (一個熱毛巾) (ee-guh ruh maow-jeen) (a hot towel)

yíge shī máojīn 一个湿毛巾 (一個濕毛巾) (ee-guh shir maow-jeen) (a wet towel)

yíge shī máojīn 一个湿毛巾 (一個濕毛巾) (ee-guh shir maow-jeen) (a wet towel)

Talkin’ the Talk

Audrey and William meet after work in New York and decide where to eat.

William:

Audrey, nǐ hǎo!

Audrey, nee how!

Audrey, hi!

Audrey:

Nǐ hǎo. Hǎo jiǔ méi jiàn.

nee how. how jyoe may jyan.

Hi there. Long time no see.

William:

Nǐ è bú è?

nee uh boo uh?

Are you hungry?

Audrey:

Wǒ hěn è. Nǐ ne?

waw hun uh. nee nuh?

Yes, very hungry. How about you?

William:

Wǒ yě hěn è.

waw yeah hun uh.

I’m also pretty hungry.

Audrey:

Wǒmen qù Zhōngguóchéng chī Zhōngguó cài, hǎo bù hǎo?

waw-men chyew joong-gwaw-chuhng chir joong-gwaw tsye, how boo how?

Let’s go to Chinatown and have Chinese food, okay?

William:

Hǎo. Nǐ zhīdào Zhōngguóchéng nǎ jiā cānguǎn hǎo ma?

how. nee jir-daow joong-waw-chuhng nah jya tsahn-gwahn how ma?

Okay. Do you know which restaurant in Chinatown is good?

Audrey:

Běijīng kǎo yā diàn hǎoxiàng bú cuò.

bay-jeeng cow ya dyan how-shyang boo tswaw.

The Peking Duck place seems very good.

William:

Hǎo jíle. Wǒmen zǒu ba.

how jee-luh. waw-men dzoe bah.

Great. Let’s go.

Understanding what’s on the menu

Are you a vegetarian? If so, you want to order sùcài 素菜 (sue-tsye) (vegetable dishes). If you’re a dyed-in-the-wool carnivore, however, you should definitely keep your eye on the kind of hūncài 荤菜 (葷菜) (hwun-tsye) (meat or fish dishes) listed on the càidān 菜单 (菜單) (tsye-dahn) (menu). Unlike the rice or noodles you may order, which come in individual bowls for everyone at the table, the cài 菜 (tsye) (dishes) you order arrive on large plates, which you’re expected to share with others.

You should become familiar with the basic types of food on the menu in case you have only Chinese characters and pīnyīn Romanization to go on. Having this knowledge allows you to immediately know which section to focus on (or, likewise, to avoid).

Take meat, for example. In English, the words for pork, beef, and mutton have no hints of the words for the animals themselves, such as zhū 猪 (豬) (joo) (pig), niú 牛 (nyoe) (cow), or yáng 羊 (yahng) (lamb). Chinese is much simpler. Just combine the word for the animal and the word ròu 肉 (row), meaning meat, such as zhū ròu 猪肉 (豬肉) (joo row) (pork), niú ròu 牛肉 (nyoe row) (beef), or yáng ròu 羊肉 (yahng row) (mutton). Voilà! You have the dish.

Table 8-2 shows the typical elements of a Chinese menu.

Table 8-2 Typical Sections of a Chinese Menu

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

diǎnxīn 点心 (點心) |

dyan-sheen |

dessert |

|

hǎixiān 海鲜 (海鮮) |

hi-shyan |

seafood dishes |

|

jī lèi 鸡类 (雞類) |

jee lay |

poultry dishes |

|

kāiwèicài 开胃菜 (開胃菜) |

kye-way-tsye |

appetizer |

|

ròu lèi 肉类 (肉類) |

row lay |

meat dishes |

|

sùcài 素菜 |

soo-tsye |

vegetarian dishes |

|

tāng 汤 (湯) |

tahng |

soup |

|

yǐnliào 饮料 (飲料) |

een-lyaow |

drinks |

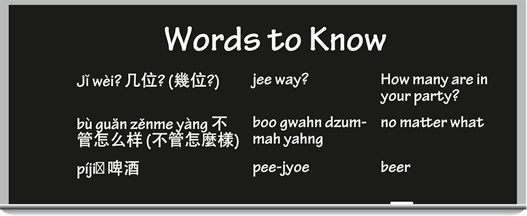

Talkin’ the Talk

Host:

Jǐ wèi?

jee way?

How many are in your party?

Otto:

Sān wèi.

sahn way.

There are three of us.

The host shows them to their table. The three must now decide what to order for their meals.

Host:

Qǐng zuò zhèr. Zhè shì càidān.

cheeng dzwaw jar. jay shir tsye-dahn.

Please sit here. Here’s the menu.

Otto:

Nǐ yào chī fàn háishì yào chī miàn?

nee yaow chir fahn hi-shir yaow chir myan?

Do you want to eat rice or noodles?

Ernest:

Liǎngge dōu kěyǐ.

lyahng-guh doe kuh-yee.

Either one is fine.

Cecilia:

Wǒ hěn xǐhuān yāoguǒ jīdīng. Nǐmen ne?

waw hun she-hwan yaow-gwaw jee-deeng. nee-men nuh?

I love diced chicken with cashew nuts. How about you guys?

Ernest:

Duìbùqǐ, wǒ chī sù. Wǒmen néng bù néng diǎn yìdiǎr dòufu?

dway-boo-chee, waw chir soo. waw-mun nung boo nung dyan ee-dyar doe-foo?

Sorry, I’m a vegetarian. Can we order some tofu?

Cecilia:

Dāngrán kěyǐ.

dahng-rahn kuh-yee.

Of course we can.

Otto:

Bù guǎn zěnme yàng, wǒmen lái sān píng píjiǔ, hǎo bù hǎo?

boo gwahn dzummuh yahng, waw-mun lye san peeng pee-jyoe, how boo how?

No matter what, let’s get three bottles of beer, okay?

Ernest:

Hěn hǎo!

hun how!

Very good!

Vegetarian’s delight

If you’re a vegetarian, you may feel lost when looking at a menu filled with mostly pork (the staple meat of China), beef, and fish dishes. Not to worry. As long as you memorize a couple of the terms shown in Table 8-3, you won’t go hungry.

Table 8-3 Vegetables Commonly Found in Chinese Dishes

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

bōcài 菠菜 |

baw-tsye |

spinach |

|

dòufu 豆腐 |

doe-foo |

bean curd |

|

fānqié 番茄 |

fahn-chyeh |

tomato |

|

gāilán 芥兰 (芥蘭) |

gye-lahn |

Chinese broccoli |

|

mógū 蘑菇 |

maw-goo |

mushroom |

|

qiézi 茄子 |

chyeh-dzuh |

eggplant |

|

qīngjiāo 青椒 |

cheeng-jyaow |

green pepper |

|

sìjídòu 四季豆 |

suh-jee-doe |

string bean |

|

tǔdòu 土豆 |

too-doe |

potato |

|

xīlánhuā 西兰花 (西蘭花) |

she-lahn-hwah |

broccoli |

|

yáng báicài 洋白菜 |

yahng bye-tsye |

cabbage |

|

yùmǐ 玉米 |

yew-me |

corn |

|

zhúsǔn 竹笋 (竹筍) |

joo-swoon |

bamboo shoot |

When you have a good understanding of the vegetables that go into Chinese dishes, you, oh proud vegetarian, can start to order specialized vegetarian dishes at all your favorite restaurants. Table 8-4 shows some vegetarian dishes good for a night on the town.

Table 8-4 Vegetarian Dishes

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

dànhuā tāng 蛋花汤 (蛋花湯) |

dahn-hwah tahng |

egg drop soup |

|

gānbiān sìjìdòu 干煸四季豆 (乾煸四季豆) |

gahn-byan suh-jee-doe |

sautéed string beans |

|

hóngshāo dòufu 红烧豆腐 (紅燒豆腐) |

hoong-shaow doe-foo |

braised bean curd in soy sauce |

|

suān là tāng 酸辣汤 (酸辣湯) |

swan lah tahng |

hot-and-sour soup |

|

yúxiāng qiézi 鱼香茄子 (魚香茄子) |

yew-shyang chyeh-dzuh |

spicy eggplant with garlic |

Some favorite Chinese dishes

You may be familiar with many of the following dishes if you’ve ever been in a Chinese restaurant:

Běijīng kǎo yā 北京烤鸭 (北京烤鴨) (bay-jeeng cow yah) (Peking roast duck)

Běijīng kǎo yā 北京烤鸭 (北京烤鴨) (bay-jeeng cow yah) (Peking roast duck)

chūnjuǎn 春卷 (春捲) (chwun-jwan) (spring roll)

chūnjuǎn 春卷 (春捲) (chwun-jwan) (spring roll)

dòufu gān 豆腐干 (豆腐乾) (doe-foo gahn) (dried beancurd)

dòufu gān 豆腐干 (豆腐乾) (doe-foo gahn) (dried beancurd)

gàilán niúròu 芥兰牛肉 (芥蘭牛肉) (guy-lahn nyoe-row) (beef with broccoli)

gàilán niúròu 芥兰牛肉 (芥蘭牛肉) (guy-lahn nyoe-row) (beef with broccoli)

gōngbǎo jīdīng 宫保鸡丁 (宮保雞丁) (goong-baow jee-deeng) (diced chicken with hot peppers)

gōngbǎo jīdīng 宫保鸡丁 (宮保雞丁) (goong-baow jee-deeng) (diced chicken with hot peppers)

háoyóu niúròu 蚝油牛肉 (蠔油牛肉) (how-yo nyoe-row) (beef with oyster sauce)

háoyóu niúròu 蚝油牛肉 (蠔油牛肉) (how-yo nyoe-row) (beef with oyster sauce)

húntūn tāng 馄饨汤 (餛飩湯) (hwun-dwun tahng) (wonton soup)

húntūn tāng 馄饨汤 (餛飩湯) (hwun-dwun tahng) (wonton soup)

shuàn yángròu 涮羊肉 (shwahn yahng-row) (Mongolian hot pot)

shuàn yángròu 涮羊肉 (shwahn yahng-row) (Mongolian hot pot)

tángcù yú 糖醋鱼 (糖醋魚) (tahng-tsoo yew) (sweet-and-sour fish)

tángcù yú 糖醋鱼 (糖醋魚) (tahng-tsoo yew) (sweet-and-sour fish)

yān huángguā 腌黄瓜 (醃黃瓜) (yan hwahng-gwah) (pickled cucumber)

yān huángguā 腌黄瓜 (醃黃瓜) (yan hwahng-gwah) (pickled cucumber)

Sauces and seasonings

The Chinese use all kinds of seasonings and sauces to make their dishes so tasty. Check out Chinese Cooking For Dummies by Martin Yan (Wiley) for much more info. Here are just a few of the basics:

cù 醋 (tsoo) (vinegar)

cù 醋 (tsoo) (vinegar)

jiǎng 姜 (jyahng) (ginger)

jiǎng 姜 (jyahng) (ginger)

jiàngyóu 酱油 (醬油) (jyahng-yo) (soy sauce)

jiàngyóu 酱油 (醬油) (jyahng-yo) (soy sauce)

làyóu 辣油 (lah-yo) (hot sauce)

làyóu 辣油 (lah-yo) (hot sauce)

máyóu 麻油 (mah-yo) (sesame oil)

máyóu 麻油 (mah-yo) (sesame oil)

yán 盐 (鹽) (yan) (salt)

yán 盐 (鹽) (yan) (salt)

Even though Chinese food is so varied and great you could have it three meals a day forever, once in a while you might really find yourself hankering for a good old American hamburger or a stack of French fries. In fact, you may be surprised to find places like McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken in Asia when you least expect to. Table 8-5 lists some items you can order when you’re in need of some old fashioned comfort food, and Table 8-6 lists common beverages.

Table 8-5 Western Food

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

bǐsā bǐng 比萨饼 (比薩餅) |

bee-sah beeng |

pizza |

|

hànbǎobāo 汉堡包 (漢堡包) |

hahn-baow-baow |

hamburger |

|

káo tǔdòu 烤土豆 |

cow too-doe |

baked potato |

|

règǒu 热狗 (熱狗) |

ruh-go |

hot dog |

|

sānmíngzhì 三明治 |

sahn-meeng-jir |

sandwich |

|

shālā jiàng 沙拉酱 (沙拉醬) |

shah-lah jyahng |

salad dressing |

|

shālā zìzhùguì 沙拉自助柜 (沙拉自助櫃) |

shah-lah dzuh-joo-gway |

salad bar |

|

tǔdòuní 土豆泥 |

too-doe-nee |

mashed potatoes |

|

yáng pái 羊排 |

yahng pye |

lamb chops |

|

yìdàlì shì miàntiáo 意大利式面条 (意大利式麵條) |

ee-dah-lee shir myan-tyaow |

spaghetti |

|

zhà jī 炸鸡 (炸雞) |

jah jee |

fried chicken |

|

zhà shǔtiáo 炸薯条 (炸薯條) |

jah shoo-tyaow |

French fries |

|

zhà yángcōng quān 炸洋葱圈 (炸洋蔥圈) |

jah yahng-tsoong chwan |

onion rings |

|

zhū pái 猪排 (豬排) |

joo pye |

pork chops |

Table 8-6 Beverages

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

chá 茶 |

chah |

tea |

|

gān hóng pūtáojiǔ 干红葡萄酒 (干紅葡萄酒) |

gahn hoong poo-taow-jyoe |

dry red wine |

|

guǒzhī 果汁 |

gwaw-jir |

fruit juice |

|

kāfēi 咖啡 |

kah-fay |

coffee |

|

kělè 可乐 (可樂) |

kuh-luh |

soda |

|

kuāngquánshuǐ 矿泉水 (礦泉水) |

kwahng-chwan-shway |

mineral water |

|

níngmén qìshuǐ 柠檬汽水 (檸檬汽水) |

neeng-muhng chee-shway |

lemonade |

|

niúnǎi 牛奶 |

nyoe-nye |

milk |

|

píjiǔ 啤酒 |

pee-jyoe |

beer |

Placing an order and chatting with the wait staff

Chinese table etiquette dictates that everyone decides together what to order. The two main categories you must decide on are the cài 菜 (tsye) (food dishes) and the tāng 汤 (湯) (tahng) (soup). Feel free to be the first one to ask Wǒmen yīnggāi jiào jǐge cài jǐge tāng? 我们应该叫几个菜几个汤? (我們應該叫幾個菜幾個湯?) (waw-men eeng-gye jyaow jee-guh tsye jee-guh tahng?) (How many dishes and how many soups should we order?) Ideally, one of each of the five major tastes should appear in the dishes you choose for your meal to be a “true” Chinese meal: suān 酸 (swan) (sour), tián 甜 (tyan) (sweet), kǔ 苦 (koo) (bitter), là 辣 (lah) (spicy), and xián 咸 (shyan) (salty).

I know it can be hard to choose what to eat from all the fantastic choices staring back at you from most any Chinese menu; after all, the Chinese perfected the art of cooking long before the French and Italians appeared on the scene. But when you finally hit on something you like, you have to figure out how to tell the waiter what you want to chī 吃 (chir) (eat), whether you like spicy food, if you want to avoid wèijīng 味精 (way-jeeng) (MSG), what kind of beer you want to hē 喝 (huh) (drink), and that you want to know what kind of náshǒu cài 拿手菜 (nah-show tsye) (house specialty) the restaurant has going today.

Here are some questions your waiter or waitress is likely to ask you:

Nǐmen yào hē diǎr shénme? 你们要喝点儿什么? (你們要喝點兒甚麼?) (nee-men yaow huh dyar shummuh?) (What would you like to drink?)

Nǐmen yào hē diǎr shénme? 你们要喝点儿什么? (你們要喝點兒甚麼?) (nee-men yaow huh dyar shummuh?) (What would you like to drink?)

Nǐmen yào shénme cài? 你们要什么菜? (你們要甚麼菜?) (nee-men yaow shummuh tsye?) (What would you like to order? [Literally: What kind of food would you like?])

Nǐmen yào shénme cài? 你们要什么菜? (你們要甚麼菜?) (nee-men yaow shummuh tsye?) (What would you like to order? [Literally: What kind of food would you like?])

Yào jǐ píng píjiǔ? 要几瓶啤酒? (要幾瓶啤酒?) (yaow jee peeng pee-jyoe?) (How many bottles of beer do you want?)

Yào jǐ píng píjiǔ? 要几瓶啤酒? (要幾瓶啤酒?) (yaow jee peeng pee-jyoe?) (How many bottles of beer do you want?)

When addressing waiters or waitresses, you can call them by the same name: fúwùyuán 服务员 (服務員) (foo-woo-ywan) (service personnel). In fact, he, she, and it all share the same Chinese word, too: tā 他/她/它 (tah). Isn’t that easy to remember? Here are some questions, requests, and statements that may come in handy:

Dà shīfu náshǒu cài shì shénme? 大师傅拿手菜是什么? (大師傅拿手菜是甚麼?) (dah shir-foo nah-show tsye shir shummuh?) (What’s the chef’s specialty?)

Dà shīfu náshǒu cài shì shénme? 大师傅拿手菜是什么? (大師傅拿手菜是甚麼?) (dah shir-foo nah-show tsye shir shummuh?) (What’s the chef’s specialty?)

Nǐ gěi wǒmen jièshào cài, hǎo ma? 你给我们介绍菜, 好吗? (你給我們介紹菜, 好嗎?) (nee gay waw-men jyeh-shaow tsye how ma?) (Can you recommend some dishes?)

Nǐ gěi wǒmen jièshào cài, hǎo ma? 你给我们介绍菜, 好吗? (你給我們介紹菜, 好嗎?) (nee gay waw-men jyeh-shaow tsye how ma?) (Can you recommend some dishes?)

Nǐmen yǒu kuàngquán shuǐ ma? 你们有矿泉水吗? (你們有礦泉水嗎?) (nee-men yo kwahng-chwan shway mah?) (Do you have any mineral water?)

Nǐmen yǒu kuàngquán shuǐ ma? 你们有矿泉水吗? (你們有礦泉水嗎?) (nee-men yo kwahng-chwan shway mah?) (Do you have any mineral water?)

Qǐng bǎ yǐnliào sòng lái. 请把饮料送来. (請把飲料送來.) (cheeng bah yin-lyaow soong lye.) (Please bring our drinks.)

Qǐng bǎ yǐnliào sòng lái. 请把饮料送来. (請把飲料送來.) (cheeng bah yin-lyaow soong lye.) (Please bring our drinks.)

Qǐng bié fàng wèijīng, wǒ guòmǐn. 请别放味精, 我过敏. (請別放味精, 我過敏.) (cheeng byeh fahng way-jeeng, waw gwaw-meen.) (Please don’t use any MSG, I’m allergic.)

Qǐng bié fàng wèijīng, wǒ guòmǐn. 请别放味精, 我过敏. (請別放味精, 我過敏.) (cheeng byeh fahng way-jeeng, waw gwaw-meen.) (Please don’t use any MSG, I’m allergic.)

Qǐng cā zhuōzi. 请擦桌子. (請擦桌子.) (cheeng tsah jwaw-dzuh.) (Please wipe off the table.)

Qǐng cā zhuōzi. 请擦桌子. (請擦桌子.) (cheeng tsah jwaw-dzuh.) (Please wipe off the table.)

Qǐng gěi wǒ càidān. 请给我菜单. (請給我菜單.) (cheeng gay waw tsye-dahn.) (Please give me the menu.)

Qǐng gěi wǒ càidān. 请给我菜单. (請給我菜單.) (cheeng gay waw tsye-dahn.) (Please give me the menu.)

Wǒ bù chī zhūròu. 我不吃猪肉. (我不吃豬肉.) (waw boo chir joo-row.) (I don’t eat pork.)

Wǒ bù chī zhūròu. 我不吃猪肉. (我不吃豬肉.) (waw boo chir joo-row.) (I don’t eat pork.)

Wǒ bù néng chī yǒu táng de cài. 我不能吃有糖的菜. (waw boo nuhng chir yo tahng duh tsye.) (I can’t eat anything made with sugar.)

Wǒ bù néng chī yǒu táng de cài. 我不能吃有糖的菜. (waw boo nuhng chir yo tahng duh tsye.) (I can’t eat anything made with sugar.)

Wǒ bú yào là de cài. 我不要辣的菜. (waw boo yaow lah duh tsye.) (I don’t want anything spicy.)

Wǒ bú yào là de cài. 我不要辣的菜. (waw boo yaow lah duh tsye.) (I don’t want anything spicy.)

Wǒ bú yuànyì chī hǎishēn. 我不愿意吃海参. (我不願意吃海參.) (waw boo ywan-yee chir hi-shun) (I don’t want to try sea slugs.)

Wǒ bú yuànyì chī hǎishēn. 我不愿意吃海参. (我不願意吃海參.) (waw boo ywan-yee chir hi-shun) (I don’t want to try sea slugs.)

Wǒ méi diǎn zhèige. 我没点这个. (我没点這個.) (waw may dyan jay-guh.) (I didn’t order this.)

Wǒ méi diǎn zhèige. 我没点这个. (我没点這個.) (waw may dyan jay-guh.) (I didn’t order this.)

Wǒmen yào yíge suān là tāng. 我们要一个酸辣汤. (我們要一個酸辣湯.) (waw-men yaow ee-guh swan lah tahng.) (We’d like a hot-and-sour soup.)

Wǒmen yào yíge suān là tāng. 我们要一个酸辣汤. (我們要一個酸辣湯.) (waw-men yaow ee-guh swan lah tahng.) (We’d like a hot-and-sour soup.)

Yú xīnxiān ma? 鱼新鲜吗? (魚新鮮嗎?) (yew shin-shyan mah?) (Is the fish fresh?)

Yú xīnxiān ma? 鱼新鲜吗? (魚新鮮嗎?) (yew shin-shyan mah?) (Is the fish fresh?)

Dipping into some dim sum

Dim sum is probably the most popular food of Chinese folks in the United States and of people in Guangdong Province and all over Hong Kong, where you can find it served for breakfast, lunch, and sometimes dinner. Vendors even sell dim sum snacks in subway stations.

The dish’s main claim to fame is that it takes the shape of mini portions, and it’s often served with tea to help cut through the oil and grease afterwards. You have to signal the waiters when you want a dish of whatever is on the dim sum cart they push in the restaurant, however, or they just pass on by. Dim sum restaurants are typically crowded and noisy, which only adds to the fun.

Part of the allure of dim sum is that you get to sample a whole range of different tastes while you catch up with old friends. Dim sum meals can last for hours, which is why most Chinese people choose the weekends to have dim sum. No problem lingering on a Saturday or Sunday.

Because dim sum portions are so small, your waiter often tallys the total by the number of plates left on your table. You can tell the waiter you want a specific kind of dim sum by saying Qǐng lái yì dié _____. 请来一碟 _____. (請來一碟 _____.) (cheeng lye ee dyeh _______.) (Please give me a plate of _____.). Fill in the blank with one of the tasty choices I list in Table 8-7.

Table 8-7 Common Dim Sum Dishes

|

Chinese |

Pronunciation |

English |

|

chūnjuǎn 春卷 (春捲) |

chwun-jwan |

spring rolls |

|

dàntǎ 蛋挞 (蛋撻) |

dahn-tah |

egg tarts |

|

dòushā bāo 豆沙包 |

doe-shah baow |

sweet bean buns |

|

guō tiē 锅贴 (鍋貼) |

gwaw tyeh |

fried pork dumplings |

|

luóbō gāo 萝卜糕 (蘿蔔糕) |

law-baw gaow |

turnip cake |

|

niàng qīngjiāo 酿青椒 (釀青椒) |

nyahng cheeng-jyaow |

stuffed peppers |

|

niúròu wán 牛肉丸 |

nyoe-row wahn |

beef balls |

|

xiā jiǎo 虾饺 (蝦餃) |

shyah jyaow |

shrimp dumplings |

|

xiǎolóng bāo 小笼包 (小籠包) |

shyaow-loong baow |

steamed pork buns |

|

xiā wán 虾丸 (蝦丸) |

shyah wahn |

shrimp balls |

|

yùjiǎo 竽饺 (芋餃) |

yew-jyaow |

deep fried taro root |

Nǐ qù guò Měiguó méiyǒu? 你去过美国没有?(你去過美國沒有?) (nee chew gwaw may-gwaw mayo?) (Have you ever been to America?)

Nǐ chī guò Yìdàlì fàn ma? 你吃过意大利饭吗? (你吃過意大利飯嗎?) (nee chir gwaw ee-dah-lee fahn ma?) (Have you ever eaten Italian food?)

Finding the restrooms

After you have a bite to eat, you may be in need of a restroom. The need may be dire if you’re smack in the middle of a 12-course banquet in Beijing and already have a couple of glasses of máotái 茅台 (maow-tye), the stiffest of all Chinese drinks, under your belt.

Now all you have to do is garner the energy to ask Where’s the restroom?: Cèsuǒ zài nǎr? 厕所在哪儿? (廁所在哪兒?) (tsuh-swaw dzye nar?) if you’re in mainland China or Cèsuǒ zài nǎlǐ? 厕所在哪里? (廁所在哪理?) (tsuh-swaw dzye nah-lee?) if you’re in Taiwan. You can also ask Nǎlǐ kěyǐ xǐ shǒu? 哪里可以洗手? (哪裡可以洗手?) (nah-lee kuh-yee she show?) (Where can I wash my hands?)

Finishing your meal and paying the bill

After you’re through sampling all possible permutations of Chinese cuisine (or French or Italian, for that matter), you won’t be able to just slink away unnoticed out the front door and into the sunset. Time to pay the bill, my friend. Hopefully it was worth the expense. Here are some phrases you should know when the time comes:

Bāokuò fúwùfèi. 包括服务费. (包括服務費.) (baow-kwaw foo-woo-fay.) (The tip is included.)

Bāokuò fúwùfèi. 包括服务费. (包括服務費.) (baow-kwaw foo-woo-fay.) (The tip is included.)

fēnkāi suàn 分开算 (分開算) (fun-kye swahn) (to go Dutch)

fēnkāi suàn 分开算 (分開算) (fun-kye swahn) (to go Dutch)

jiézhàng 结账 (結賬) (jyeh-jahng) (to pay the bill)

jiézhàng 结账 (結賬) (jyeh-jahng) (to pay the bill)

Qǐng jiézhàng. 请结账. (請結賬.) (cheeng jyeh-jahng.) (The check, please.)

Qǐng jiézhàng. 请结账. (請結賬.) (cheeng jyeh-jahng.) (The check, please.)

Qǐng kāi shōujù. 请开收据. (請開收據.) (cheeng kye show-jyew.) (Please give me the receipt.)

Qǐng kāi shōujù. 请开收据. (請開收據.) (cheeng kye show-jyew.) (Please give me the receipt.)

Wǒ kěyǐ yòng xìnyòng kǎ ma? 我可以用信用卡吗? (我可以用信用卡嗎?) (waw kuh-yee yoong sheen-yoong kah mah?) (May I use a credit card?)

Wǒ kěyǐ yòng xìnyòng kǎ ma? 我可以用信用卡吗? (我可以用信用卡嗎?) (waw kuh-yee yoong sheen-yoong kah mah?) (May I use a credit card?)

Wǒ qǐng kè. 我请客. (我請客.) (waw cheeng kuh.) (It’s on me.)

Wǒ qǐng kè. 我请客. (我請客.) (waw cheeng kuh.) (It’s on me.)

Zhàngdān yǒu cuò. 账单有错. (賬單有錯.) (jahng-dahn yo tswaw.) (The bill is incorrect.)

Zhàngdān yǒu cuò. 账单有错. (賬單有錯.) (jahng-dahn yo tswaw.) (The bill is incorrect.)

All the Tea in China

You encounter about as many different kinds of tea as you do Chinese dialects. Hundreds, in fact. To make ordering or buying this beverage easier, however, you really need to know only the most common kinds of tea:

Lǜ chá 绿茶 (綠茶) (lyew chah) (Green tea): Green tea is the oldest of all the teas in China, with many unfermented subvarieties. The most famous kind of Green tea is called lóngjǐng chá 龙井茶 (龍井茶) (loong-jeeng chah), meaning Dragon Well tea. You can find it near the famous West Lake region in Hangzhou, but people in the south generally prefer this kind of tea.

Lǜ chá 绿茶 (綠茶) (lyew chah) (Green tea): Green tea is the oldest of all the teas in China, with many unfermented subvarieties. The most famous kind of Green tea is called lóngjǐng chá 龙井茶 (龍井茶) (loong-jeeng chah), meaning Dragon Well tea. You can find it near the famous West Lake region in Hangzhou, but people in the south generally prefer this kind of tea.

Hóng chá 红茶 (紅茶) (hoong chah) (Black tea): Even though hóng means red in Chinese, you translate this phrase as Black tea instead. Unlike Green tea, Black teas are fermented; they’re enjoyed primarily by people in Fujian province.

Hóng chá 红茶 (紅茶) (hoong chah) (Black tea): Even though hóng means red in Chinese, you translate this phrase as Black tea instead. Unlike Green tea, Black teas are fermented; they’re enjoyed primarily by people in Fujian province.

Wūlóng chá 乌龙茶 (烏龍茶) (oo-loong chah) (Black Dragon tea): This kind of tea is semi-fermented. It’s a favorite in Guangdong and Fujian provinces in the South, and in Taiwan.

Wūlóng chá 乌龙茶 (烏龍茶) (oo-loong chah) (Black Dragon tea): This kind of tea is semi-fermented. It’s a favorite in Guangdong and Fujian provinces in the South, and in Taiwan.

Mòlì huā chá 茉莉花茶 (茉莉花茶) (maw-lee hwah chah) (Jasmine): This kind of tea is made up of a combination of Black, Green, and Wūlóng teas in addition to some fragrant flowers such as jasmine or magnolia thrown in for good measure. Most northerners are partial to Jasmine tea, probably because the north is cold and this type of tea raises the body’s temperature.

Mòlì huā chá 茉莉花茶 (茉莉花茶) (maw-lee hwah chah) (Jasmine): This kind of tea is made up of a combination of Black, Green, and Wūlóng teas in addition to some fragrant flowers such as jasmine or magnolia thrown in for good measure. Most northerners are partial to Jasmine tea, probably because the north is cold and this type of tea raises the body’s temperature.

hǎochī 好吃 (how-chir) (tasty [Literally: good to eat])

hǎohē 好喝 (how-huh) (tasty [Literally: good to drink])

hǎokàn 好看 (how-kahn) (pretty, interesting [Literally: good to look at or watch]) This designation can apply to people or even movies.

hǎowán 好玩 (how-wahn) (fun, interesting [Literally: good to play])

Taking Your Chinese to Go

Restaurants are great, but once in a while you may want to mingle with the masses as people go about buying food for a home-cooked family dinner. Outdoor food markets abound in China and are great places to see how the locals shop and what they buy. And what better way to try out your Chinese? You can always point to what you want and discover the correct term for it from the vendor.

In addition to clothes, books, and kitchen utensils, outdoor markets may offer all sorts of food items:

Ròu 肉 (row) (meat): niú ròu 牛肉 (nyoe row) (beef), yáng ròu 羊肉 (yahng row) (lamb), or jī ròu 鸡肉 (雞肉) (jee row) (chicken)

Ròu 肉 (row) (meat): niú ròu 牛肉 (nyoe row) (beef), yáng ròu 羊肉 (yahng row) (lamb), or jī ròu 鸡肉 (雞肉) (jee row) (chicken)

Shuǐguǒ 水果 (shway-gwaw) (fruit): píngguǒ 苹果 (蘋果) (peeng-gwaw) (apples) or júzi 桔子 (jyew-dzuh) (oranges)

Shuǐguǒ 水果 (shway-gwaw) (fruit): píngguǒ 苹果 (蘋果) (peeng-gwaw) (apples) or júzi 桔子 (jyew-dzuh) (oranges)

Yú 鱼 (魚) (yew) (fish): xiā 虾 (蝦) (shyah) (shrimp), pángxiè 螃蟹 (pahng-shyeh) (crab), lóngxiā 龙虾 (龍蝦) (loong-shyah) (lobster), or yóuyú 鱿鱼 (魷魚) (yo-yew) (squid)

Yú 鱼 (魚) (yew) (fish): xiā 虾 (蝦) (shyah) (shrimp), pángxiè 螃蟹 (pahng-shyeh) (crab), lóngxiā 龙虾 (龍蝦) (loong-shyah) (lobster), or yóuyú 鱿鱼 (魷魚) (yo-yew) (squid)

Making comparisons

Here are a few examples:

Píngguǒ bǐ júzi hǎochī. 苹果比桔子好吃. (蘋果比橘子好吃.) (peeng-gwaw bee jyew-dzuh how-chir.) (Apples are tastier than oranges.)

Tā bǐ nǐ niánqīng. 她比你年轻 (年輕). (tah bee nee nyan-cheeng.) (She’s younger than you.)

Zhèige fànguǎr bǐ nèige fànguǎr guì. 这个饭馆比那个饭馆贵. (這個飯館比那個飯館貴.) (jay-guh fahn-gwar bee nay-guh fahng-gwar gway.) (This restaurant is more expensive than that one.)

How much is that thousand-year-old egg?

When you’re ready to buy some foodstuffs, here are two simple ways to ask how much the products cost:

Duōshǎo qián? 多少钱? (多少錢?) (dwaw-shaow chyan?) (How much money is it?)

Duōshǎo qián? 多少钱? (多少錢?) (dwaw-shaow chyan?) (How much money is it?)

Jǐkuài qián? 几块钱? (幾塊錢?) (jee-kwye chyan?) (Literally: How many dollars does it cost?)

Jǐkuài qián? 几块钱? (幾塊錢?) (jee-kwye chyan?) (Literally: How many dollars does it cost?)

The only difference between the two questions is the implied amount of the cost. If you use the question word duōshǎo 多少 (dwaw-shaow), you want to inquire about something that’s most likely more than $10. If you use jǐ 几 (幾) (jee) in front of kuài 块 (塊) (kwye) (dollars), you assume the product costs less than $10. (You can also use jǐ in front of suì 岁 (歲) (sway) (years) when you want to know how old a child under 10 is.)

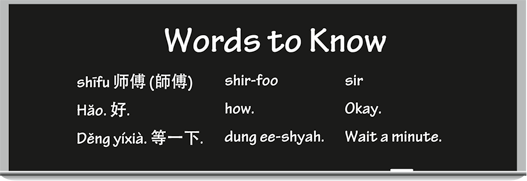

Talkin’ the Talk

Margaret:

Shīfu, qǐng wèn, nǐ yǒu méiyǒu bōcài?

shir-foo, cheeng one, nee yo mayo baw-tsye?

Sir, may I ask, do you have any spinach?

Shīfu:

Dāngrán. Yào jǐjīn?

dahng-rahn. yaow jee-jeen?

Of course. How many kilograms would you like?

Emmanuel:

Wǒmen mǎi sānjīn, hǎo bùhǎo?

waw-men my sahn-jeen, how boo-how?

Let’s get three kilograms, okay?

Margaret:

Hǎo. Sānjīn ba.

how. sahn-jeen bah.

Okay. It’ll be three kilograms then.

Shīfu:

Méi wèntǐ. Yìjīn sān kuài qián. Nèmme, yiígòng jiǔ kuài.

may one-tee. ee-jeen sahn kwye chyan. nummuh, ee-goong jyoe kwye.

No problem. It’s $3 a kilogram. So that will be $9 all together.

Emmanuel:

Děng yíxià. Bōcài bǐ gàilán guì duōle. Wǒmen mǎi gàilán ba.

dung ee-shyah. baw-tsye bee guy-lahn gway dwaw- luh. waw-mun my guy-lahn bah.

Wait a minute. Spinach is more expensive than Chinese broccoli. Let’s buy Chinese broccoli then.

Shīfu:

Hǎo. Gàilán liǎngkuài yìjīn. Hái yào sānjīn ma?

how. guy-lahn lyahng-kwye ee-jeen. hi yaow sahn-jeen mah?

Okay. Chinese broccoli is $2 a kilogram. Do you still want three kilograms?

Margaret:

Shì de.

shir duh.

Yes.

Shīfu:

Nà, sānjīn yígòng liù kuài.

nah, sahn-jeen ee-goong lyo kwye.

In that case, three kilograms will be $6.

Emmanuel:

Hǎo. Zhè shì liù kuài.

how. juh shir lyoe kwye.

Okay. Here’s $6.

Shīfu:

Xièxiè.

shyeh-shyeh.

Thank you.

Emmanuel:

Xièxiè. Zàijiàn.

shyeh-shyeh. dzye-jyan.

Thanks. Goodbye.

Shīfu:

Zàijiàn.

dzye-jyan.

Goodbye.

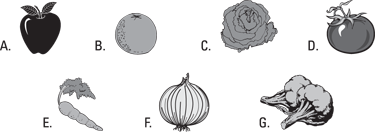

Fun & Games

Fun & Games

Identify these fruits and vegetables and write their Chinese names below. Check out Appendix D for the answers.

A. __________________________

B. __________________________

C. __________________________

D. __________________________

E. __________________________

F. __________________________

G. __________________________

In China,

In China,

If you hear the sound

If you hear the sound

You ask for something politely by saying

You ask for something politely by saying