If you were to place your hand on the speaker of a radio or stereo system while it is on, you could feel the vibrations the sounds make. These vibrations are what you “hear.” However, if you lost your hearing, you could never train yourself to experience the vibrations in your hand as sound. Nonetheless, the human body does have a well developed sense of touch. This chapter discusses the mechanical senses (other than hearing): touch (pain, temperature changes) and balance (the ability to ascertain limb and body position).

Feedback from the visual system (which acts as a motion detector) and the vestibular system is responsible for maintaining your balance. The vestibular system is located in the inner ear and consists of the three semicircular canals that are next to the cochlea (see Figure 4-1). Like the organ of Corti in the cochlea, the semicircular canals are filled with fluid and contain hair cells that detect the fluid’s movement. Imagine a pole going through the top of your head to the floor (a vertical axis) and a horizontal sheet through your head from ear to ear (a horizontal axis). The semicircular canals detect rotation along these axes as well as any movement along the horizontal axis from front to back.

Signals from the semicircular canals are involved in the vestibulospinal reflex, a balance reflex that involves the cortex, the cerebellum (the structure at the back of the brain), and the spinal cord. Signals from the semicircular canals are combined with signals from the retina and cortex that detect motion in the same direction detected in the semicircular canals. This allows for the visual system and the vestibular system to work in unison to obtain your orientation in space, to feel and coordinate motion, and to help with balance control (mostly for balance standing up). This system for balance control operates through your core or trunk. When you fall or slip in one direction, say toward the left, you may extend your left leg and left arm to counteract the fall and restore your balance. This system signals for that corrective response.

A person with vestibular damage would have trouble reading a street sign while walking. This is because the vestibular system allows the brain to shift eye movements to compensate for changes in head position. Without this ability, the experience of reading while walking would be like trying to read a severely jiggling book.

The sense of balance is accomplished by complex neural processes that are distributed throughout the spinal cord, vestibular system, visual system, and the cerebellum. Of course, your sense of balance is strongly associated and works with the ability to move. However, some researchers consider the sense of balance a sixth sense that should be included with the other five senses and insist that balance is a “perception” much like vision or hearing.

Sensations from the body are called somatosensations. The somatosensory system is made up of three interacting systems:

An exteroceptive system that responds to stimuli applied to the skin (there are three subdivisions here: touch, temperature, and pain receptors).

The proprioceptive system that monitors information about the position of the body (this includes the vestibular system previously discussed).

The interoceptive system that provides information concerning conditions inside the body, such as temperature.

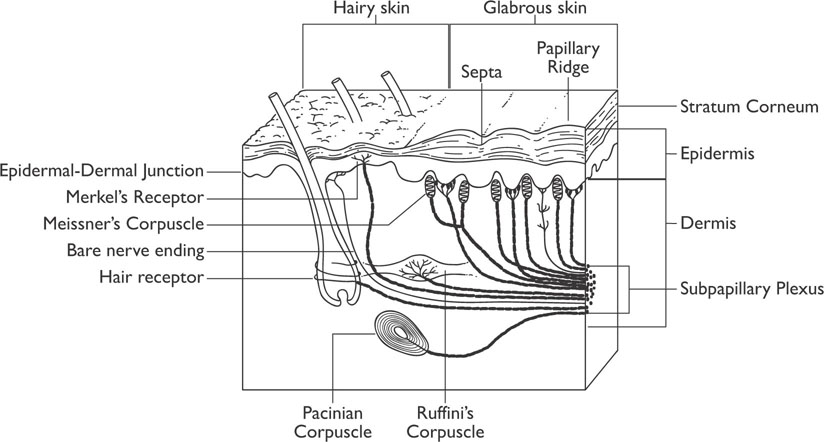

The exteroceptive system is the focus of this section. The skin has a number of different receptors. The simplest cutaneous (skin) receptors are called free nerve endings, which are unspecialized neural endings that are particularly sensitive to temperature changes on the skin and to painful stimuli. The lamellated corpuscles are the deepest and largest cutaneous receptors. These receptors respond to sudden changes in pressure on the skin (they respond quickly), whereas Merkel’s discs and Ruffini endings respond to gradual pressure and skin stretch (both of these receptors respond more slowly). Figure 5-1 shows a cross-section of the skin.

Figure 5-1: Receptors in the Skin

When the skin is touched, or pressure is applied to the skin, the stimulation results in a firing of all the receptors, which leads to the perception of being touched. After a very short time (a few hundred milliseconds), the slowly adapting receptors remain activated and the fast receptors deactivate, which changes the quality of the perception. Imagine putting on a hat: at first you can feel it on your head, but rather quickly the perception goes away unless you focus on it. Receptors that adapt at different rates allow for the organism to receive information concerning static and dynamic qualities of stimuli. Somatosensory receptors are specialized in such a manner that a particular type of receptor responds to a particular type of stimulus; however, the receptors all function in a similar manner. When they are stimulated, the chemistry of the receptors is altered, allowing the cell membrane to exchange ions in the same manner as occurs during the action potential of a neuron. The neural fibers that carry information from the somatosensory receptors (skin and other receptors) join together as nerves and enter the spinal cord by way of the dorsal roots (on the back of the spine).

Dermatomes are areas of the body that are innervated by a particular segment of a dorsal root spinal cord section. If a specific dorsal root nerve is destroyed, there is often not significant somatosensory loss as there is considerable overlap between dermatomes that are next to each other. A reference for viewing the dermatomes is provided in Appendix B.

There are two major pathways that transmit somatosensory information from the body to the brain. The dorsal column–medial lemniscus system tends to relay information about touch and proprioception, whereas the anterolateral system tends to relay information about pain and temperature changes to the brain. However, the disconnection of one system does not eliminate the type of information sent to the brain by that system, so the division of these functions between the two systems is not complete. Both systems must relay both types of information to some extent.

The dorsal column–medial lemniscus sensory roots (for touch) enter the spinal cord from their sources by means of a dorsal root (a path in the back of the spinal cord) and travel up in the dorsal columns to the dorsal column nuclei in the medulla (where the spinal cord connects to the hindbrain). It is at this point where they synapse (relay the signal). The axons of the dorsal column nuclei cross over (decussate) to the other side of the brain and connect to the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus by way of nerves known as the medial lemniscus. The ventral posterior nucleus also receives projections from three branches of the trigeminal nerve that carry information from the opposite side of the face. Most of the neurons in the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus send projections to the primary somatosensory cortex of the brain; however some send projections to the secondary somatosensory cortex in the posterior parietal lobe.

Are all neurons the same length?

Neurons can be of differing lengths depending on their targets. The longest neurons in the human body are the dorsal column neurons that begin in the toes and run up to the medulla.

In contrast to the dorsal column–medial lemniscus, the neurons in the anterolateral dorsal roots (pain perception) synapse when they enter the spinal cord. The axons of the second order neurons either decussate (cross over) and continue up to the brain or move up the spinal cord on the same side as they entered. There are three different tracts of the anterolateral dorsal root system:

A spinothalamic tract that projects directly to the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus

A spinoreticular tract that projects to the reticular formation and then to the thalamus (at two different sites called the parafascicular and intralaminar nuclei)

The spinotectal tract that connects to the tectum (roof) of the midbrain

The three branches of the trigeminal nerve previously mentioned also carry information regarding pain and temperature from the other side of the face to these sites in the thalamus. Once the information reaches the thalamus, it is then sent on to the primary somatosensory cortex or the secondary somatosensory cortex.

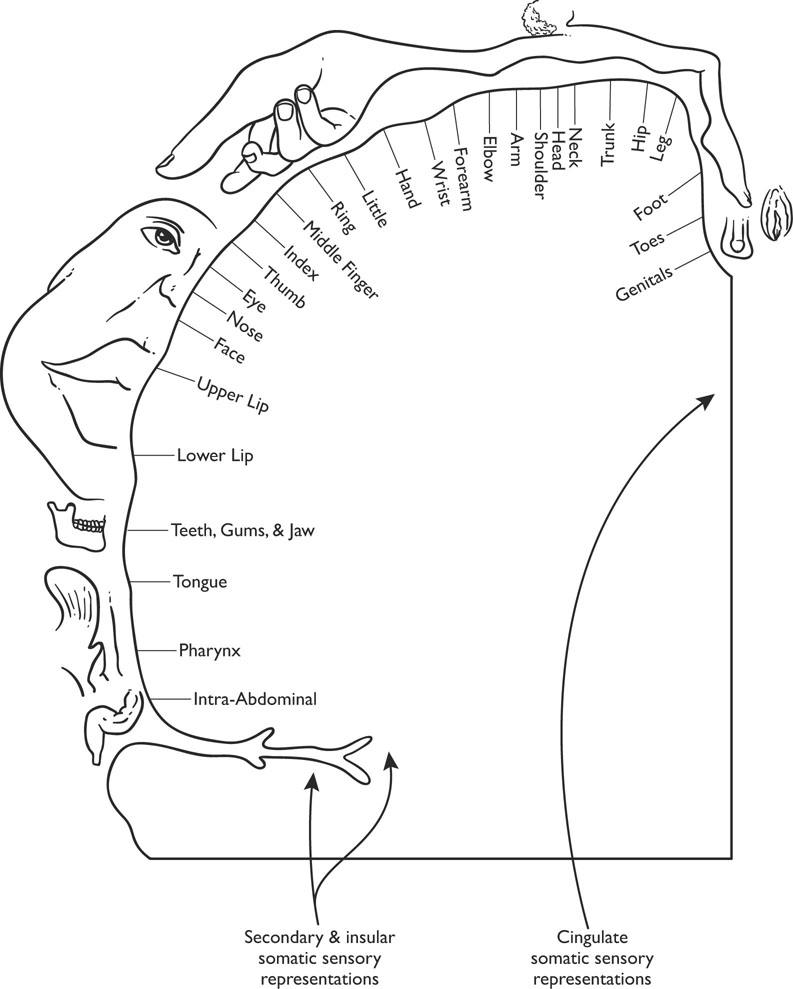

The signals of touch and pain are processed in the thalamus and then sent to the appropriate cortical areas. The primary somatosensory cortex (sometimes referred to as SI) is located directly posterior to the central fissure at the very anterior portion of the parietal lobe and is organized according to a map of the body surface commonly called the “somatosensory homunculus” (homunculus means “little man”). Thus, the somatosensory cortex is often referred to as being somatotopic in organization. Figure 5-2 displays the organization of the primary somatosensory cortex.

Figure 5-2: Sensory Homunculus

The “homunculus” in the somatic sensory cortex is disproportional in that more area of the somatosensory cortex receives inputs from the parts of the body that make tactile discriminations, such as the hands, lips, tongue, etc., than from other parts of the body. Areas of the body, such as the back, have proportionately smaller representations in the somatosensory cortex. The secondary somatosensory cortex (sometimes called SII) lies inferior to the primary somatosensory cortex, and much of it extends into the lateral fissure. The secondary somatosensory cortex receives a great deal of its input from the primary somatosensory cortex and thus receives information from both sides of the body, whereas the primary somatosensory cortex receives its input from the contralateral (opposite) side of the body (cortex on the left side of the brain receives information from the right side of the body and vice versa). Both areas of the somatosensory cortex send much of their output to the association cortex in the posterior portion of the parietal lobe of the brain. Neurons in the primary somatosensory cortex are either excitatory or inhibitory and display the columnar organization discussed in Chapter 3. Neurons in a column tend to respond to the same type of stimulation, whereas neurons across columns respond to different types of stimulation.

The signals from the somatosensory cortex are sent to areas of the prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex association areas. The association areas in the posterior parietal cortex contain neurons that respond to both somatosensory stimuli and visual stimuli (neurons that respond to two types of stimulation are called bimodal neurons). The two receptive fields of each neuron are related in a spatial manner; for example, if a particular neuron’s somatosensory receptive field is in the right hand, then its visual field is next to the right hand. As the hand moves, the visual receptive field moves with it.

One of the reasons for the discrepancy in the amount of different cortical areas allotted to different areas on the body is that different areas of the skin have different densities of receptors for touch. The fingertips and tongue have many more receptors than do similarly sized areas of skin located on the back. These areas of higher receptor density allow for much finer discriminations.

There is evidence that parts of the cortex can become more or less activated when one anticipates that they are about to be touched. For example, one study found that activity in the primary sensory motor cortex increased, and activation in the areas outside the primary sensory motor cortex decreased, when people were anticipating being tickled, a pattern similar to activity observed during actual tickling. The motor area of the frontal cortex must receive projections from the somatosensory system in order to make a decision about what to do in response to stimulation. When it receives this information, the motor area and the frontal cortex can generate the appropriate action.

Touch and pressure are signaled by the corpuscles in the skin, whereas pain is signaled by the nociceptors, which are specialized cells that may be myelinated or unmyelinated. The myelinated fibers conduct information about pain very quickly and, when these cells are activated, there is usually an immediate reaction, such as when you touch a hot stove and pull your hand away immediately even before you’re aware of what you’ve done. The unmyelinated cells are involved in the duller and longer-lasting types of pain.

The perception of pain is actually considered paradoxical by many brain researchers. The perception of pain actually has no apparent representation in the human cortex. In fact, the perception of painful stimuli appears to result in the activation of many areas of the human cortex, but these areas vary from study to study and between participants in studies. Painful stimuli typically lead to activation in the primary and secondary somatosensory cortices; however, these brain areas do not appear to be necessary for one to experience pain. For instance, studies of individuals who have had a cerebral hemisphere surgically removed indicate that they can still experience pain on the side opposite the removed cerebral hemisphere. Pathways for pain to the CNS are diffuse, have short-term or long-term effects, and can have many different connections.

While painful experiences are indeed unpleasant, another paradox of pain is that these experiences are often necessary and important for survival. Pain is designed to be a sort of intense warning to stop some harmful or potentially harmful activity or to seek treatment for an injury. However, an interesting paradox of pain is that it can often be suppressed by emotional or cognitive factors. Athletes have been known to accomplish amazing feats with broken bones that would make most people fall down and cry. Some religious ceremonies require participants to pierce their bodies, and yet these participants often express or feel little pain, and soldiers and people injured in life-threatening situations frequently feel no pain until the event is over.

A theory regarding pain that has been quite influential is the gate control theory of pain. This theory proposes that signals descending from the brain are able to activate neural mechanisms in the spinal cord (neural gates) that can block incoming neural pain signals to the brain. If a person is sufficiently distracted, the gate can close and the experience of pain can be lessened or blocked altogether.

There is evidence for the gate control theory of pain. The cerebral aqueduct is in the midbrain, contains cerebrospinal fluid, and connects the third and fourth ventricles. The gray matter around the cerebral aqueduct is called the periaqueductal gray matter (PAG). The PAG contains special receptors for opiate-based drugs like morphine and codeine. Why would the brain have built-in receptors for synthetic drugs? As it turns out, your brain also produces several endorphins, which are endogenous opiate neurotransmitters that can block the perception of pain. The discovery of these endorphins and the PAG answered questions as to why people could block pain perception under certain circumstances as well as why certain drugs relieve pain.

The brain has a built-in pain control system that occurs when output from the PAG excites a cluster of nuclei in the core of the medulla, known as the raphe nuclei, causing them to release the neurotransmitter serotonin. The serotonin release results in a signal sent on the dorsal columns of the spinal cord that blocks incoming pain signals into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (recall that pain signals enter the dorsal part of the spinal cord from the skin and other parts of the body). It has also been hypothesized that the placebo effect that is often seen in studies where participants, who are given a pill that they are told will block their pain but are actually given an inert compound, still report a reduction in their pain. Somehow, the placebo interacts with the patient’s beliefs and activates the gate blocking mechanism.

Pain perception can work both ways, however. For example, some of the descending neural circuits can increase, instead of blocking pain, as when someone is fearful or under a great deal of stress. Pain perception appears to activate the anterior cingulate cortex of the brain. The cingulate cortex is located in between hemispheres just above the corpus callosum (in the mesocortex). The front part of the cingulate cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, may be a sensitive monitoring center in the brain. This area is activated by painful stimuli, the anticipation that one will experience a painful stimulus, and failure in obtaining one’s goals. The purpose of such a center in the brain appears to be concerned with sorting out different strategies to obtain goals. For example, if you were bitten by a large brown dog, you may find yourself feeling anxious whenever you see a large brown dog, thus resulting in avoiding the dog and avoiding potential pain.

Different stimuli are often paired together, as in the anticipation of pain and going to the dentist. Sometimes two different stimuli become associated with a particular outcome. This process is called conditioning and is a form of learning that can produce voluntary or involuntary responses to the stimuli.

Pain thresholds and individuals are variable, and the ability to tolerate pain is also quite variable among different people and within the same person in different situations. Some studies suggest that pain tolerance increases as people get older, but it is not clear as to whether this finding is due to decreased sensitivity in the system, psychological factors, or other factors. Athletes and people with high levels of motivation appear to have higher pain tolerances, and there have been suggestions that people from different cultural backgrounds display different tolerances for pain. This last finding may be related to the cultural appropriateness of expressing pain that differs from culture to culture.

Peripheral neuropathy occurs when pain receptors in the peripheral nervous system become inactive or die as a result of vascular problems. This leads to a loss of feeling in the affected limb. Peripheral neuropathy typically occurs in the fingers or toes of affected individuals.

Sometimes your brain can fool you as in cases of people who have phantom limb sensation or phantom pain. The phantom limb sensation results from the ability of the brain to change in response to stimuli. This physical change in the brain tissue is known as neuroplasticity or just plasticity. Most individuals who have a limb amputated continue to have the sensation that the limb is still present. This experience is termed a phantom limb. Even though the limb has been amputated, the neurons in the somatosensory cortex still continue to send signals as if the limb were still there. Eventually the phantom limb sensation will dissipate. Phantom limb sensations result from the neuroplasticity of the brain. Because there are no incoming signals from the amputated limb, the neurons associated with the phantom limb, needing stimulation, may connect with adjacent cortical areas. Often, stroking the area of the body whose cortical representation is adjacent to that of the amputated limb produces the sensation that the amputated limb is being stroked (e.g., stroking the left side of the face or left shoulder produces the sensation that the amputated left hand is being stroked).

Neuropathic pain is chronic pain that occurs without a recognizable cause. This typically develops after an injury has healed, but the person continues to experience extreme pain. The mechanism producing neuropathic pain is unknown, but recent research suggests that abnormal glial cells in the brain produce signals that lead to hyperactivity in the pain pathways. Neuropathic pain can also occur following an amputated limb.

Phantom pain is experienced in nearly half of all amputees. The mechanism for this extreme pain is not yet understood, but it is hypothesized that either it is due to changes in the primary sensory cortex after amputation (neuroplasticity), conflicting signals received from the amputated limb and from the visual system that sends motor commands to the amputated limb, or innate memories of limb position.