Honeys vary in colour, thickness, clarity, scent and flavour depending on their nectar and honeydew sources, their processing and their storage.

Honey is arguably best eaten warm from the hive. Most of us, though, purchase honey from grocery stores, supermarkets, farmers’ markets or even online.

Honeycomb ‘sections’ are sold in small wooden frames taken from a hive’s honey boxes (‘supers’). Pieces of honeycomb packed in wooden or plastic containers are called cut-comb honey. Chunk honey comes as a jar of runny honey containing one or more pieces of honeycomb. When eating honeycomb, some people chew it like gum, then either swallow the bits of wax or spit them out. Honeycomb is easier to eat if beekeepers have furnished hives with commercially made beeswax starter sheets. This is because their wax is thinner than in honeycomb made entirely by bees.

Most honey comes as runny or thick honey. Both have been drained or pressed from the comb, or spun out by a rotary extractor. Thick honey has either crystallized (granulated) and therefore thickened naturally or has been ‘creamed’ (see page 40). Runny honey is sometimes presented in squeezy plastic bottles rather than glass or ceramic jars or pots. It’s also sold in sealed single-use plastic straws (honey sticks) so that it can easily be added to coffee or ice cream, for example, away from home.

After being extracted from the comb, most honey is heated to:

• Reduce its viscosity, to ease straining (or filtering) and bottling (packing).

• Delay crystallization, to keep it runny for longer.

• Kill yeasts, to prevent fermentation.

Heat of more than 40ºC/104°F begins to evaporate honey’s volatile flavour compounds and inactivate its enzymes, while more than 49ºC/120ºF destroys the enzymes.

However, most commercially available honeys are heated to 66ºC/150ºF (pasteurized) to deter crystallization and fermentation. Heating to this temperature or higher also enables a process called ultra-filtration, in which honey is pressurized through a very fine filter to make it very clear and remaining runny for longer. The faster honey is heated and subsequently cooled, the less damage there is.

The US Department of Agriculture identifies seven honey colours: water-white, extra-white, white, extra-light amber, light-amber, amber and dark-amber. Certain honeys even have yellow, pink, red, green, blue or even black tones.

A honey’s colour depends on its nectar and honeydew sources, the soil and season in which its source plants grew, and its processing and storage.

Plants grown on clay, for example, give rise to darker honeys than those on sandy soils. Autumn, tropical and honeydew honeys are often dark. Heating can darken honey; honey stored at above 0ºC/32ºF slowly darkens; and honey stored in reused honeycomb darkens by absorbing plant pigments from propolis on the comb. Dark honeys often taste strong because they tend to have relatively more maltose, minerals, acids and antioxidant flavonoids. They also tend to have less glucose and fructose, so taste relatively less sweet.

Spring honeys are usually pale. Light-coloured honeys tend to have relatively more glucose, so crystallize more quickly. They have a mild taste.

Honey is runny (uncrystallized) or thick (crystallized) depending on its source plants, processing and age. Most honeys start off runny, but almost all thicken in time, some much faster than others. Some honeys have a gel-like consistency, but liquefy if shaken. Worldwide, most consumers prefer thick honey, though most US consumers like runny honey. Runny honeys vary in viscosity, thick honeys in firmness. Viscous honeys tend to crystallize more slowly than runny ones. Slow-to-crystallize honey eventually tends to form large crystals that can have a gritty texture.

Processors can delay crystallization by heating honey, or by straining or filtering it to remove the pollens, dust, air bubbles and fragments of wax, propolis and bee parts that trigger natural crystallization.

The more glucose a honey contains, the more rapid is the formation of glucose-monohydrate crystals. Crystallization frees the water in which glucose was dissolved, making any remaining uncrystallized honey more watery. Crystallization takes a few hours for high-glucose honeys, a few weeks or months for medium-glucose honeys and a few years for lowglucose honeys. Darker honeys and tropical honeys are generally low in glucose. Some low-glucose honeys remain runny almost indefinitely. Some high-glucose honeys even crystallize in the hive. Certain bell-heather honeys, for example, are so thick that the comb must be crushed before the honey can be extracted. Fast-crystallizing honeys form smaller crystals and are therefore smoother in texture.

Crystallization is also influenced by certain other sugars. Sucrose speeds it up, and maltose slows it down. Melezitose hardens certain honeydew honeys so much that they can’t be removed from a hive’s honey-box frames; they are called ‘cement honey’.

Processors sometimes induce crystallization by ‘creaming’. This thickens runny honey yet prevents coarse crystallization. High-glucose honeys such as clover, leatherwood and sunflower that naturally thicken quickly are ideal for creaming.

First, processors pasteurize the honey to prevent fermentation. Next they ‘seed’ it by stirring in one part of finely crystallized honey (of the same variety) to nine parts of runny honey. Then they cool it. This triggers very fine crystallization, producing smooth, easy-to-spread creamed honey (also called spun, whipped, candied, granulated, churned or soft-set honey, or honey fondant).

Processors sometimes convert coarsely crystallized honey into smooth honey by heating to liquefy it, then seeding it.

Cloudiness in a runny honey generally results from pollens. Frosting around its edge is caused by small air-filled spaces developing during crystallization. Cloudiness can also come from suspended particles of wax, propolis, bee parts and dust. Thick honey is opaque.

Honey labelled raw should not have been:

• Heated. Because even just using an electrically heated knife to cut wax cappings from honeycomb could affect the honey.

• Filtered. Instead, it’s simply strained through a wide stainless-steel mesh. Very clear honey has almost certainly been heated to enable filtering, so isn’t truly raw.

• Creamed.

• Irradiated.

Raw honey is gently poured or otherwise mechanically removed from the comb, then left for about a week so that risen debris and bubbles can be skimmed off.

Compared with heated honey, raw honey has higher levels of enzymes and scent and flavour compounds. And there is no risk of any other constituents having been altered by heat.

Raw honey is available from beekeepers, farmers’ markets and gourmet or organic food stores.

Certified organic honey is free from pesticides and antibiotics. Regulations vary from country to country, but European Union certification, for example, requires the following:

• The hive is kept on land certified as organic.

• Land within 3km of the hive is uncultivated or cultivated organically.

• The land on which the hives are kept is unaffected by significant pollution.

• The hive is made from natural untreated timber.

• The hive has been managed organically for 12 months or more.

• The wax is organic.

• Feeding of bees is with organic honey or sugar, and only between the last honey harvest and 15 days before the first nectar flow.

• Priority for disease control is to build health and vitality through positive management. Unrestricted use of herbal treatments and natural acids (lactic, formic, oxalic) is allowed. After using a prescribed medication such as an antibiotic, the wax must be replaced, and organic status is withdrawn for a year.

Blended honeys are the main offerings. Mixed floral (multifloral or polyfloral) honeys are also widely available. But there is growing interest in monofloral (varietal or unifloral) honeys.

This has a major input from the nectar of only one particular plant species. This plant may grow in profusion (for example, a crop such as oilseed rape, or the major local tree or wild flower, such as lime, or ling-heather). Or it may be a prolific nectar producer with easily accessible nectar (such as clover or Asclepias milkweed). Beekeepers note the flowers their bees visit. If most are of one species, the honey harvested within a day or two of the nectar flow ceasing will be a monofloral honey.

Honeys are sometimes labelled with the name of a particular flower if that species supplies 45 per cent or more of the nectar sources: for example, chestnut nectar forms 85 per cent of most chestnut honey. A higher percentage is extremely unusual, because although bees exhibit flower fidelity, they are rarely entirely faithful! Also, they need a variety of nectars and pollens for good health.

Some monofloral honeys contain less than 45 per cent of one type of nectar. For example, sunflower honey often contains 40 per cent, alfalfa and rosemary 30, linden 25, and acacia, lavender, ling-heather and sage only 20.

Wild flowers account for few monofloral honeys as they are usually so scattered. Exceptions include milkweed, purple loosestrife, rosebay willowherb (fireweed), sainfoin, smartweed, star thistle and wild carrot, all of which are sometimes available as monofloral honeys.

Most honeys are made from the nectars and honeydews from many plant species, with no one being predominant. Examples include summer, autumn, jungle and rainforest honeys, and wildflower honeys. Clover honey’s flavour lends such a characteristic stamp to a multifloral honey that this is sometimes sold as ‘clover honey’.

Blending different honeys, sometimes from different countries, can lighten the colour, reduce unwanted bitterness (for example, from almond honey) and, if one constituent honey is prone to early crystallization, keep it runny.

Any honey can contain some honeydew, but ‘honeydew honey’ contains more. It’s sometimes sold as ‘forest’ or ‘tree’ honey. Summer and autumn honeys are the most likely to contain honeydew. Honeydew honey tends to be dark, with strong fig, aniseed or woody flavour notes, depending on its sources.

Tree sources of honeydew include beech, cedar, chestnut, citrus, fir, hickory, juniper, larch, lime, maple, oak, pine, poplar, spruce and willow. Pine and other evergreens are the main source in Europe, beeches in New Zealand. Pine, larch or beech honey is often rich in honeydew. Honeydew honey from fir, larch, linden, oak and spruce trees is rich in melezitose, so hardens fast.

Plant sources of honeydew include alfalfa, beans, clover and wheat.

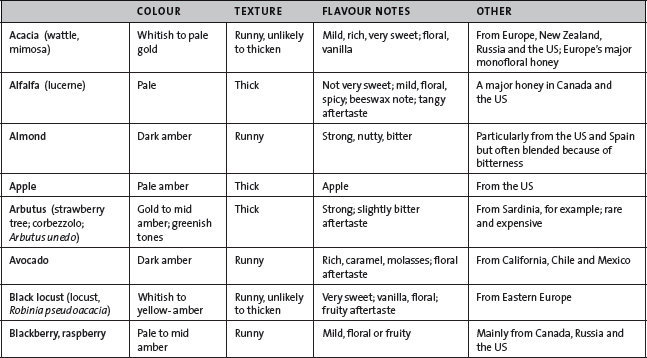

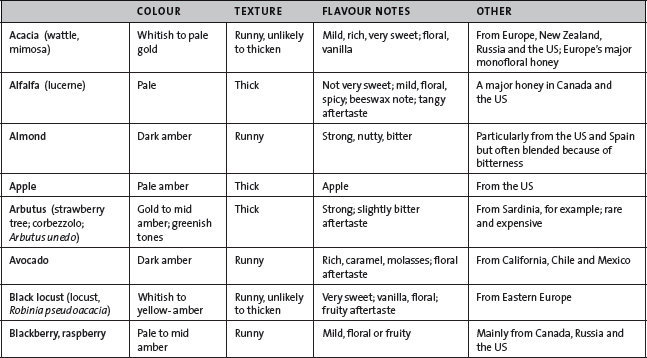

The following table’s ‘texture’ column lists a newly harvested honey’s texture. However, most honeys eventually thicken, and any can be creamed.

My favourite is wild carrot honey, produced in Sicily. Others I particularly enjoy are bell heather, buckwheat, clover, ivy, leatherwood, orange, rosemary, tawari and thyme.

Many people pick out apple, black locust, blackberry, milkweed, purple loosestrife, rosebay willowherb, sage and star thistle as being especially good. Everyone has his or her own favourites.

Most honey sold in the UK and US comes from elsewhere, with China and South America the frontrunners. Much is heat-treated and blended. Cheap runny honeys are the most likely to have been pasteurized.

Labelling regulations vary. Ideally, a label should record a honey’s weight, whether it has been heated, whether it’s monofloral or blended, the country of origin, and where it was packed. A best-before date and the producer’s name and address may be given. Any added ingredients should be listed, with their percentages. Sometimes packers add flavourings, for example.

European Union officials are even debating whether pollen – a natural part of honey – should be listed. This sounds odd, given that pollen is a natural ingredient of honey. But it might be sensible as a few people are allergic to pollen, but could consume honey that has been filtered enough to make it pollen-free. Recently, a beekeeper who found genetically modified (GM) pollen in his honey successfully sued the State of Bavaria, which owned trial crops of GM corn (maize). So now levels higher than 0.9 per cent of GM pollen in a honey sold in the EU must be listed, too. As no health risks have been shown from GM pollen, this decision may be to placate the anti-GM lobby.

Occasionally, consumers are misled. For example, while the labels of certain honeys suggest that they are from the home country, they may have been imported (sometimes via a circuitous route to avoid import tariffs or reduce suspicion of adulteration), then just packed in the home country. Also, a ‘100 per cent pure’ label might mean only that the product contains some pure honey. The runnier a honey, and the faster its bubbles rise when the jar is turned upside-down, the more likely it is to contain added sugar syrup.

Finally, some honeys claiming to be monofloral contain only very little of that particular honey.

Aim to buy from trustworthy suppliers: for example, from beekeepers at farmers’ markets or from reputable stores.

It’s worth trying different honeys, noting that:

• Sweeter honeys, which are relatively richer in fructose, go well with cheese.

• When cooking with honey, some of its flavour ingredients will be lost, so you might as well use a cheaper one.

• Mild honeys are better for delicately flavoured dishes and for seafood.

• Strongly flavoured honeys are good on bread, scones or pancakes, on vanilla ice cream, with savoury sauces and meats.

• Acacia honey is good for sweetening drinks without giving a pronounced honey flavour.

• Floral or nutty flavoured honeys suit many desserts.

Bright light destroys glucose oxidase, the honey enzyme that enables hydrogen-peroxide production. So keep honey in a dark place, or in an opaque or dark glass jar, to preserve its antimicrobial power.

Store honey at a cool room temperature.

Honey stored in the refrigerator thickens. If borage honey is refrigerated, it develops a chewy texture like toffee. Most runny honeys crystallize fastest at 14ºC/57ºF. Freezing honey prevents changes in its composition, and the process of freezing runny honey prevents natural crystallization.

Honey stored at warm room temperature may darken and taste stronger because its acidity and enzymes cause a:

• 13 per cent decrease in glucose

• 5.5 per cent decrease in fructose

• 68 per cent increase in maltose

• Slight increase in sucrose

• 13 per cent increase in higher sugars

• 22 per cent increase in unanalysed material.

Because glucose decreases more than fructose, thick honey tends to liquefy when stored at warm room temperature.

Damp air encourages water absorption, which could eventually make honey liquefy or ferment (causing bubbling, cloudiness and an ‘off’ taste). A plastic container is more air-permeable than a glass or ceramic one. Honey can be stored for years in a glass or glazed ceramic container with a tight lid. Indeed, sealed pots of honey in good condition have been found in 4,000-year-old Egyptian tombs!

In general, properly stored honey keeps well. But storing honey for six months diminishes its antioxidant power by 30 per cent. And storing it for two years begins to reduce its antibacterial power.

Keep runny honey in a drip-free syrup dispenser.

If sweetening a hot drink, wait until it’s at a drinkable temperature before adding 1–3 teaspoons of honey.

Liquefying thick honey makes it easier to pour and mix. To do this, stand a glass or a microwave-safe ceramic container of honey in hot but not boiling water for 15 minutes and stir occasionally. Or microwave an open glass jar of honey on low for 30 seconds, stir and repeat if necessary. Do this only in a microwave with a turntable, since ‘hot spots’ could otherwise spoil the honey’s flavour. Note that heating honey to 40ºC/104ºF begins to destroy its enzymes – and the hotter the temperature, the greater the losses.

Honey caramelizes at 70-80ºC/160-176ºF, with thick honey caramelizing at a lower temperature than runny honey. Caramelization means sucrose is starting to break down into glucose and fructose, producing flavour compounds such as diacetyl (which tastes of butter or butterscotch), hydroxymethylfurfural (which tastes of butter or caramel) and maltol (which tastes slightly burnt).

When measuring honey, coat the spoon or the inside of the measuring bowl or cup with vegetable oil so the honey can slip out easily.

If you would prefer to weigh the honey instead of measuring its volume when using a recipe, note that:

The honey in 1 tablespoonful weighs about 23g/¾oz.

The honey in 1 standard measuring cup (240ml/8 fl oz) weighs about 350g/12oz.

You can substitute honey for sugar in most baking recipes, but:

For each 220g/7oz/1 cup of sugar replaced, use only 165g/5oz/¾ cup of honey, plus one extra tablespoon.

When baking honey-containing cakes and biscuits, reduce the oven temperature by 20ºC/25°F as they brown more easily.

Honey can contain potentially toxic substances, or Clostridium botulinum spores. It can also trigger pollen or honey allergy in susceptible people. Thankfully, problems are extremely rare.

If potentially toxic substances (such as granayotoxin and pyrrolizidine alkaloids, page 30, certain antibiotics, page 35, and certain pesticides, page 36) are present, their amounts are usually too small to be a problem.

When swallowed into the warm, wet, low-oxygen, low-acid stomach of a baby under one year, Clostridium botulinum bacteria spores can germinate and produce botulinum toxin. This can cause botulism within 10 days, with possible symptoms including dizziness, blurred vision and paralysis. One in 100 babies hospitalized with botulism from any food dies.

Honey-consumption is associated with infant botulism in less than one in five cases. Infant botulism is rare indeed in babies of more than six months old. Also, no known case has been attributed to honey in the UK, at least.

Honey often used to be given to older babies. Now, though, to be on the safe side, most experts recommend that babies under one year should not consume honey.

While rare, there are people who are allergic to pollen proteins or bee proteins and should avoid honey.

These include beeswax, pollen, royal jelly and propolis.

This contains fatty acids, wax esters, hydrocarbons, minerals and carotenoid plant pigments. It is honey-scented, melts at about 60°C/140°F and is available as pellets, granules, blocks or cakes from health food shops and pharmacies (drugstores), or in blocks or starter (‘foundation’) sheets from beekeepers and craft shops.

Beeswax is present in certain lipsticks, lip balms, body creams, mascara, eye pencils, foundations, shampoos, hair conditioners, dental floss, medical ointments and lubricants, and enteric-coated pills. It’s used to make candles, earplugs, crayons and polishes for shoes, floors, skis and surfboards, and is available as a food additive (E901 in the EU; used, for example, as a glazing agent, a clouding agent, a stabilizer and a chewing-gum texturizer). Fruit farmers use it as a graft-wax. And it can even provide a ‘green’ way of cleaning up oil spills at sea. For this it’s made into billions of minute hollow balls that float on the water and allow oil in but not water. Microorganisms attracted from the water to the wax then ‘eat’ the oil.

These colourful, amazingly shaped particles contain the precursors of plant sperms. They are made of proteins (24–60 per cent by weight), amino acids, carbohydrates, fatty oils, lecithin, vitamins (they are especially high in vitamin C), minerals, enzymes and flavonoid plant pigments.

Pollens are commercially available as pollen crumbs or tablets, and in wax cappings. Pollens processed to remove their allergens are sold as tablets.

Some people consume pollen as a health food (for example, to improve fertility, reduce high cholesterol or treat an enlarged prostate, improve circulation or liver function, or to reduce mental or physical stress); as a dietary supplement (for its protein); or to desensitize themselves against pollen allergy. However, the health claims are not sufficiently well proven to be allowed on packaging.

A hive managed in a particular way can produce just over 450g/1lb of royal jelly a year. This involves collecting royal jelly from queen cells and putting tiny amounts in empty queen cells. Worker bees think these large cells contain queen larvae, so keep them filled with royal jelly.

Royal jelly contains water, proteins, sugars, vitamins (including B5 and C), minerals, hormones, lipids, enzymes, antibacterial substances and acetylcholine. It’s commercially available in capsules or phials and used as a dietary supplement and in cosmetics.

It’s reputed to strengthen immunity, restore strength, refresh memory, regulate blood sugar, improve the blood count, rejuvenate cells, improve Parkinson’s disease and, in children, stimulate growth. But these health claims have insufficient proof so are not permitted on packaging.

Certain trees, including pines and poplars, make a resinous sap to deter predators. Bees collect this from buds and bark wounds and mix it with saliva, pollen and beeswax to form a sticky greenish-brown substance called propolis.

This contains resins and gums (50 per cent), waxes and fatty acids (30 per cent), essential oils (10 per cent), pollens (5 per cent) and other compounds (including amino acids, vitamins, flavonoids, bitters and minerals – especially iron and zinc). It smells distinctive, tastes slightly bitter, and has potent antibacterial and antiviral activity.

Propolis is available as capsules, lozenges, tinctures (alcoholic extracts) and creams. It’s used in sweets, beauty products and toothpastes. It can be mixed with white spirit to make varnish. It’s also used for sore throats, asthma, peptic ulcer, gastritis, poor circulation, burns, eczema, warts and piles, and to stimulate new-cell generation. Scientific evidence backs some of these uses.

These bee larvae and pupae are rich in vitamins A and D and protein, marketed in China, for example, as a delicacy and can be deep-fried, smoked, baked or even dipped in chocolate!