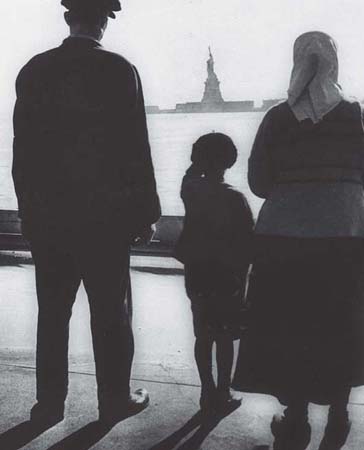

Immigrants looking at the Statue of Liberty.

CONEY ISLAND, A WILD, ISOLATED SPIT OF LAND ABUTTING AN out-of-the-way beach in the territory of New Amsterdam, was “discovered” in 1609 by Dutch explorer Henry Hudson, sailing his ship, the Half Moon, in a failed voyage to locate the riches of India. Hudson anchored his ship, went ashore, and made another discovery: people were already living there—the native Canarsee tribe.

In an attempt to make a good impression and to score some food, he traded knives and beads to members of the tribe for some corn and tobacco. The red men, whom Hudson called Indians even though India was half a world away, were savvy enough to realize that the coming of the white man did not bode well for their future, and while Hudson’s men were fishing the next day, the Indians attacked, and petty officer John Coleman was pierced in the throat by a flint-tipped arrow and killed.

Some experts believe the area was named Coney Island in honor of Coleman, but those experts don’t explain why it wasn’t called Coleman Island. Others say it wasn’t named until the early 1800s, after the Conyn family that lived there. Still others insist the name comes from konijn kok, Dutch for “rabbit hutch” or “breeding place for the rabbits”—or coneys—which were abundant there.

Though Hudson “discovered” the place, the municipality of Coney Island was not founded by the Dutch. It was started in the 1640s by an Englishwoman by the name of Deborah Moody. Born Deborah Dunch in London in 1586, she married Henry Moody, who was knighted, and so she became Lady Deborah. Six years after Sir Henry died in 1629, she was hauled in front of King Charles I’s Star Chamber. She was accused of not being a good Christian, because she believed a person should be baptized not at birth but when the person is old enough to understand the meaning of the ceremony. To be accepted by the Anglican religious community, it wasn’t enough just to be a Protestant. You had to be their type of Protestant. To do otherwise was to risk the wrath of God or, more accurately, the wrath of God’s self-appointed representatives.

In her search for religious liberty, Lady Deborah fled England for the New World in 1640. Unfortunately for Lady Deborah, who was in her fifties, her cross-Atlantic journey landed her in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where Puritan fire-breathers were just as unyielding.

Sixty percent of the Puritans who fled to the New World came from East Anglia. They had come from a poor, agricultural society, where they fought to tame the meager soil of the region. Because the Puritans conflicted with the Anglican creed, they were viewed as dangerous radicals, and they were persecuted by Anglican bishop William Laud, the Darth Vader of Puritan history.

When the twenty thousand or so Puritans settled in New England, they were defined by their strong religious beliefs. True believers who worked for the Glory of God, they were sure they had all the answers. They believed in the dignity of the individual, but saw order and discipline as “tough love.”

The Puritans, similar to the Taliban today, were a joyless lot. Cotton Mather, the psychopath who was in charge, preached that having fun was sinful. His followers weren’t allowed to sing, dance, or even celebrate Christmas. Those who defied the anti-Christmas decree “shall pay for every offense five shillings as a fine to the county.”

Pessimistic by philosophy, the Puritans saw everyone as sinners. They were tough on themselves. They beat their kids. “Spare the rod, spoil the child” was their credo. Their punishments were cruel, if not draconian. If a child was a bed wetter, they made him eat a rat sandwich. The justification was their desire to get the devil out of the child. What they ended up with was a society of punishers and abusers.

They believed in the “right” behavior, and, with order as the key to the Puritan world, their concept of liberty was to persecute those who didn’t toe the line.

By 1662 the Puritans almost died out, because the bar they set for membership was too high for most people to clear. The survivors became what we today call “Yankees,” with most becoming nose-to-the-grindstone Presbyterians.

Lady Deborah, a headstrong woman who believed in freedom of speech and the freedom to follow whatever religious doctrine she wished, risked bringing down the wrath of the church elders when she announced that she didn’t believe in the ritual of baptizing babies. Said Puritan leader John Endicott about Lady Moody: “She is a dangerous woeman [sic].”

Anyone who didn’t follow the Puritan creed was subject to severe punishment, including the humiliation of being exhibited in stocks in the public square and being shunned. As history reminds us, the extreme religious intolerance that has reared its ugly head through American history had its low point in the British colony of Puritan Massachusetts when a dozen or so unfortunates from Salem, accused of being witches, were tied to stakes and burned to death. The persecutors cited a line in Exodus. According to God’s will, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.”

This was America’s first Reign of Terror. No one dared protest for fear of becoming the next one put to the devoted, righteous Christian judge’s not-so-objective witch test. In one such test, the accused would have rocks tied to her feet. If she sank, she was “proved” to be innocent. Lady Deborah, who lived in Lynn, which was just down the road from Salem, again found herself facing the charge of not being a good Christian.

Probably because she was a baroness, her punishment was relatively light: excommunication. Though her friends begged her to stay, she decided she needed to live in a more tolerant society. She and her group of about forty Anabaptist followers headed south to find religious freedom, first traveling to Manhattan, where she was told by Dutch director general William Kieft that she could choose any area to settle from the unassigned lands of the West India Company. As she had heard, the Dutch proved to be much more tolerant and open-minded. Hoping to attract settlers, the Dutch were happy to accept anyone willing to work for the benefit of New Amsterdam.

Lady Deborah chose a way-out spot near the beach, where she and her followers could feel safe from the religious zealots. She settled in what was then the southwestern tip of Long Island, to be called Gravesend. The area, now in Brooklyn, encompasses Bensonhurst, Coney Island, Brighton Beach, and Sheepshead Bay—the first settlement in the New World founded by a woman.

When she asked Director General Kieft if the area was safe from Indians, he said it was. But Kieft would turn out to be one of the first Brooklyn politicians who not only lied but also was a bit of a crook. Lady Deborah didn’t know it, but Kieft, who felt underpaid, couldn’t resist keeping presents meant for the Indians, and they retaliated by shooting arrows at Lady Deborah’s log house. She considered returning to New England but decided against it when she was told she could only come back if she disavowed her dangerous religious ideas. For Lady Deborah, the hard-headed and hard-hearted Puritans were more dangerous than the arrow-laden redskins.

Lady Deborah was concerned that another outbreak of witch-hunting might occur—and it did, in 1799 in Virginia, with the rise of the Illuminati, a group of freemasons. Said Congregationalist minister Jedidiah Morse, who may have been the model for Senator Joe McCarthy years later, “I have now in my possession, complete and indubitable proof…an official, authenticated list of names, ages, places of nativity, professions, etc., of the officers and members of the society of Illuminati…instituted in Virginia, by the Grand Orient of France.”

Her group moved inland until a stockade could be built, and when they returned for good in 1645, Lady Moody displayed an idealistic socialist bent. Under her orders, each of the forty settlers received an equal share of the sixteen-acre plot inside the fort, along with an equal amount of farmland outside it. At town meetings, everyone was encouraged to voice an opinion.

After she demanded from the Dutch governor the right of people to practice their religion as they saw fit on Gravesend, Kieft signed a document giving Lady Moody and the other residents the right of freedom of conscience and of self-government. When Peter Stuyvesant, who replaced Kieft, made public his dislike for the Quakers, an antiwar Protestant sect that arrived in 1657, Lady Moody invited them to Gravesend, and that year the first Quaker meeting in the colonies was held in her house.

Lady Moody also advocated the fair treatment of the local Indians, giving them grazing rights to the marshes. Her advocacy of tolerance would set an example for Brooklynites far into the future. She died in 1659, at age seventy-three.

THE TOWN OF GRAVESEND, WHICH WOULD LATER BE KNOWN AS CONEY ISLAND, WAS separate and independent from the rest of Brooklyn and rather typical of the time. There was a town center, and an outlying public park that belonged to all the townspeople. Remnants of that original settlement still remain where once a stockade surrounded the town, centered on Gravesend Neck Road and McDonald Avenue.

In August 1664 the British sent four warships. Four hundred men went ashore near Coney Island. The British declared a blockade, threatened to destroy the town, and demanded Stuyvesant surrender the port.

On September 8, 1664, the Dutch, outgunned, surrendered without firing a shot. Fifty-five years after Henry Hudson’s discovery, Dutch rule was at an end.

Coney Island remained isolated and hard to reach on foot or horseback until 1829, when a private bridge was built across the creek that then separated it from the mainland. The men who built the bridge in 1829 also built the Coney Island House, intending to attract summer visitors. Among the luminaries who came were Washington Irving, Herman Melville, and the duo of P. T. Barnum and songbird Jenny Lind. Three of the more famous Civil War figures, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster, also visited. A small pier was built in 1846, which allowed excursion boats to land.

Coney Island continued to be a thorn in the side of the conservative Christian community as late as the 1850s. Sunday was supposed to be a day of rest, but Sunday excursions to the Coney Island beach to enjoy a day of swimming and dining out were common. The more devout Brooklyn churches, harking back to their Puritan roots, went so far as to threaten to ostracize parishioners who ventured on Sunday to Coney Island.

Nevertheless, Coney Island was becoming a premier tourist attraction. By the 1870s, every kind of conveyance was bringing visitors for fun in the sun. There were stagecoach lines, steam trains, horses and carriages, and even a short monorail, which ran for two years from Bensonhurst to its terminus at Coney Island. Excursion boats brought tourists across the bay. The payoff was a dinner of exotic, fresh seafood. This was an era before refrigeration, and seafood didn’t travel very well. Lundy’s restaurant, located then, as now, in Sheepshead Bay, provided one of the finest lobster dishes anywhere in the country.

By the 1880s the wealthy elite began building racetracks and hotels on Coney Island. Horse racing was illegal in the rest of New York State, but was allowed in Coney Island. Three tracks—the Sheepshead Bay racetrack, the Brighton Beach racetrack, and the Gravesend racetrack—all were built. The Coney Island Jockey Club was founded by wealthy socialites August Belmont, William R. Travers, and A. Wright Sanford, and among its judges were men on the A-list of American society: W. K. Vanderbilt, J. G. Lawrence, and J. H. Bradford.

Leonard Jerome, a flamboyant stock marker speculator and promoter, convinced state officials that their tracks should be allowed to operate, arguing that since the Coney Island racetracks were owned and operated by these elite millionaires, everyone would follow their example and keep the sport clean. “We will be the moral incentive,” he told them. It didn’t quite turn out that way, but it was a winning argument. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the top races would draw crowds of forty thousand spectators or more.

Austin Corbin, the president of the Long Island Rail Road, built a railroad line to get the horsey set to the tracks and built grand hotels to house them. Corbin built the Oriental Hotel and the Manhattan Beach Hotel, subsequently the home of the Coney Island Jockey Club, which ran the Sheepshead Bay racetrack. These were tracks for the elite, and during the off season, picnics and other events, such as military parades, were held there.

Ministers of the conservative Protestant churches, who saw gambling as a sin, complained that horse racing was attracting a rather unsavory crowd as hundreds of bookmakers handled $15 million in bets. Gambling was both big business and popular. After preachers complained in 1885 and again in 1886, William Engleman, the owner of the Brighton Beach track, was arrested and indicted on gambling charges. Each time, the jury refused to convict him.

The conservative ministers also were wary of their churchgoers taking trips to Coney Island because by the 1880s it had become an open and notorious den of sin: bars, gambling joints, cabarets where Mae West, daughter of a Coney Island cop, later tap-danced and belted out the song “My Mariooch-Maka-Da-Hoocha-Ma-Coocha,” and where houses of prostitution proliferated. You could watch chorus girls lift their legs, and then you could talk one into a private dance if the price was right.

Because it was so far from central Brooklyn, Coney Island was a place that drew its share of criminals, outlaws, and escapees. All of these crooks put together, however, didn’t fleece the populace nearly as badly as one politician/businessman by the name of John Young McKane. It was the era of William Marcy “Boss” Tweed and unchecked greed, when—like under the George W. Bush administration—the wealthy and connected had carte blanche to conduct their business any way they saw fit. The goal was to make as much money as possible at the expense of as many other people as possible. Morality was never an issue; only the final score mattered, and that was determined by how much money you made. Only the most corrupt were caught, including Tweed, the head of Tammany Hall, who, after being sentenced to prison, escaped. En route to the Caribbean and Spain, where he was rearrested, he first made a stop at Coney Island to see his buddy McKane.

McKane’s political career began when he was elected Coney Island constable in 1868. He ran on a Big Business platform, charging that the farmers who ran the town—the descendants of Lady Deborah—didn’t know much about business, that they needed a man who could raise revenues from leases on the town’s common lands near the beach.

McKane was a man who didn’t smoke or drink and who taught Sunday school at the Methodist Episcopal Church. But though he believed in Christianity, there was nothing Christian about him. For McKane, playing by the rules was for suckers. There were no rules. His goal was to use his political position to gain absolute power.

His climb to authoritarian rule was ingenious. A builder by trade, he became the town’s supervisor, a position from which McKane snatched power in the community. Whoever held the position also was chairman of the board of health, town board, water board, and board of audit. He also had the power to nominate the justices of the peace. Once he became supervisor, McKane hatched his scheme to use his political position to make his private fortune by leasing the town’s public property, “renting” these spaces to entrepreneurs who wanted to start businesses, and keeping the “rents”—payoffs—for himself.

If someone said, “I want to operate a bathhouse,” McKane would give his blessing and his company would build it. If someone wanted to open a store, McKane would give his approval and build the store. At first, in order to attract more entrepreneurs, he kept the “rents” reasonable. Though the land on which he built was not his, he was able to control all of Coney Island before the townspeople realized what he was doing. By the time they did, it was too late.

By 1876 McKane had allied himself with some of the wealthiest, most influential businessmen in America, including LIRR honcho Austin Corbin, who was seeking public land on Manhattan Beach to build a hotel. McKane agreed to “sell” Corbin the land worth $100,000 for $1,500—a price approved by the town assessor, who was in McKane’s pocket. The respectable farmers expressed their outrage that McKane was getting rich from his thievery, but when the vote came up to ratify the deal, Corbin packed the meeting with two hundred thugs armed with clubs. The sale of the property was approved.

McKane then got permission from his wealthy cronies in the legislature in Albany, in 1881, to set up his own police force. Though it was paid for with the payoffs made from his leases and licenses, McKane had the gall to proclaim that as chief of police he was serving at no salary.

Coney Island had become an authoritarian state. The town belonged to John McKane. What McKane said, went, whether it was legal or not. He made the rules and enforced them through his paid henchmen. McKane’s permission was enough to operate any saloon, gambling house, or carnival concession, in return for his getting his cut. Under McKane, prostitutes, con-gamers—like three-card-monte artists—and land swindlers plied their trade. McKane’s public philosophy was “If I don’t see it, it doesn’t exist.”

The Society for the Suppression of Vice was formed for the purpose of ending the prostitution and closing down the racetracks. Anthony Comstock, the spokesman, revealed that the pool sellers—bookies—at the three racetracks took $15 million in illegal bets. Yet when the society scheduled a raid on the bookies, they were tipped off, and nothing incriminating was found.

The all-powerful McKane made a fortune, but then he got too greedy, raising the “rents” beyond reason. He was brought before the Brooklyn Common Council and charged with corruption. He would prove difficult to convict, because almost everyone in the town was beholden to him in some way and his political allies were powerful. Many were called to testify, but they either denied knowing anything, or lied for fear of retaliation. Only one man, Peter Tilyou, a successful real estate broker, dared to stand up and risk everything by telling the truth in court about McKane’s corruption. Tilyou named every house of prostitution and gave their locations. He told of the misdeeds of McKane’s justices and chief of police. He told of McKane’s flagrant fraud of “selling” public land.

The committee doing the investigation for the assembly said that Coney Island was a “source of corruption and crime, disgraceful…and dangerous.” It called McKane “an enemy, and not a friend, of the administration of justice.” The recommendation was for Coney Island to be made a part of the city of Brooklyn and called for McKane’s indictment, prompt prosecution, and his impeachment from office.

Because he was protected by Hugh McLaughlin, the powerful Democratic Brooklyn boss, nothing happened to McKane, as the committee’s report was pigeonholed in Albany. Peter Tilyou, the whistle-blower, suffered for his stand. He had to retire from the real estate business, and his father would be stripped of his beach property and forced by McKane and his goons to leave town.

McKane would go on to become an important state and national political figure. Aligned with the powerful McLaughlin, he was even able to fix elections. Through intimidation and chicanery he was able to deliver an inordinate number of Democratic votes come election time. In 1884 his arm-twisting of the Coney Island populace provided Grover Cleveland enough of a margin to carry New York State by 1,200 votes and win the presidency.

In 1886 McKane, brimming with hubris, made a mistake. Biting the hand that fed him, he cavalierly backed a Republican assemblyman. McLaughlin demanded he resign from the Democratic state committee and from the board of supervisors.

Having switched sides to the Republicans, in 1888 McKane instructed the locals to vote straight Republican for presidential candidate Benjamin Harrison. Many of the voters’ names were taken from the Greenwood and Washington cemeteries. New York’s thirty-six electoral votes won Harrison the election. According to historian Jeffrey Stanton, this triumph of corruption was “McKane’s finest hour.”

McKane continued in power until 1893, when he again sought to fix a local election. In the past there had been one polling place, which he would pack with his armed supporters to scare away the opposition. Reformers were aware that although Coney Island had only 1,500 registered voters, McKane’s people had submitted more than 6,218 voter names. In an attempt to stop the voter fraud, the reformers passed a new rule providing for six polling places, one for each district. The idea was to prevent McKane from directly overseeing the ballot boxes.

This was an election McKane knew he could not afford to lose, because if he did, the winners would surely make him and his supporters pay, and so he knew he had to be more resourceful and unscrupulous than ever. To get around the new law, McKane came up with an ingenious solution. He gerrymandered the districts in such a way that all six polling places were located inside Coney Island’s town hall. Voters entered from six new doors cut out by McKane’s employees. Once again McKane and his goons had a ringside seat inside town hall to make sure the election went his way.

Said McKane with a straight face, “The people of Gravesend must not be interfered with, but must be let alone to do their own voting in their own way.”

When the reformers tried to enter the town hall to supervise the election, McKane had them arrested or tossed out. When he was handed an injunction to force him to let the reformers lawfully observe the election, he uttered the line “Injunctions don’t go here.” Several of the reformers were beaten unmercifully by McKane’s police.

William Gaynor, the reform candidate for New York Supreme Court justice, was sure that McKane was stuffing the ballot box against him, and he sent his men to copy the registration lists. McKane’s goons arrested them and threw them in jail, charging them with drunkenness and vagrancy.

McKane hollered to his thugs, “They’re all drunk, take ’em away, take ’em all away and lock ’em up.”

One reformer who was able to avoid arrest raced to the offices of the Brooklyn Eagle to give his account of what was happening. The wire services picked up the story, and McKane’s quote, “Injunctions don’t go here,” was repeated all over America. Convinced he was invincible, McKane was unapologetic and unconcerned.

But this was to be the year of the reformers. The new mayor of Brooklyn was a reformer. The new state attorney general was a reformer. William Gaynor, who as a youngster had been on McKane’s payroll, won his seat on the New York State Supreme Court despite McKane’s fraudulent vote-counting in Coney Island, and the angry, righteous Gaynor came looking for payback. McKane and twenty of his henchmen were indicted for voter fraud in 1894. McKane’s henchmen offered at least one juror a bribe of a house and land in exchange for a vote of innocent, but the jury was so outraged it came back with a guilty verdict. He was sentenced to six years of hard labor at Sing Sing. No one thought he’d serve it, but he did.

As McKane rode across the Brooklyn Bridge on his way to Grand Central Station for the train ride up the river, Peter Tilyou stood and cheered when the carriage went by. When questioned by reporters, Tilyou said, “This is my revenge. John Y. McKane is on his way to Sing Sing and Peter Tilyou is a poor but free man. Don’t you bet he’d change places with me now?”

With McKane’s reign at an end, a bill passed the New York State legislature that annexed Coney Island to Brooklyn. McKane, who allowed no visitors to see him during his years in jail, was released on April 30, 1898. After he suffered two strokes, he died in September of 1899.

Reformers also ultimately put an end to the racetracks. In 1908 a state law provided that the bookies would be liable for any and all debts at the tracks. When the bookies fled, the tracks died.

Though horse racing had died out, Coney Island still had its primary attractions, its four large amusement parks that had their heyday before the start of World War I.

The man who began the amusement-park craze in Coney Island was an adventurer by the name of Paul Boyton, who became famous for his swimming feats across Europe, South America, and in the United States. Boyton once donned a rubber flotation device and paddled 2,300 miles down the Mississippi.

In 1895 Boyton opened the first outdoor amusement park in the world at Coney Island—Sea Lion Park—which featured an aquatic toboggan slide and a two-passenger roller coaster that performed a loop-de-loop. It closed after wet and cloudy weather during the summer of 1902 kept the crowds away.

The second park, called Steeplechase Park, was built by Peter Tilyou’s son George, who was able to start back up in business after his father’s nemesis John Y. McKane went to jail. In 1893 George went to Chicago to see the World’s Columbian Exposition. When he saw the giant steel wheel built by George Ferris, he decided to buy it. When the wheel was sold instead to the promoters of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, he built a smaller version for himself and put it up on Coney Island. It quickly became a huge attraction. He added an aerial slide and the Double Dip Chute, and also added a very popular attraction, a ride for six customers at a time that felt like they were riding in a horse race—hence the name Steeplechase Park.

Tilyou continually searched for new attractions, and in 1901 he attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, bringing an attraction called A Trip to the Moon for the 1902 summer season. The ride was enclosed, impervious to the weather, and during that wet summer of 1902, 850,000 curiosity-seekers paid to ride A Trip to the Moon, saving Tilyou from bankruptcy. Tilyou was also one of the first to rent the newfangled bathing suits to customers. The only access to the beach was through the amusement parks, and he charged a dollar, which was a lot of money back then, to use his bathhouse and swim. Doctors of that time warned that swimming in the ocean would leach the salt out of a person’s body, so Tilyou rented heavy woolen suits that went from the neck to the ankles to prevent that. Ministers of conservative Protestant churches were quick to point out that such public bathing was a sin, because it brought together men and women who were essentially swimming in their underwear.

The third amusement park built at Coney Island was called Luna Park. It was started by Frederick Thompson and Skip Dundy, the two men who owned the Trip to the Moon ride that George Tilyou had featured at Steeplechase Park. Thompson and Dundy bought Sea Lion Park from Paul Boyton, and opened Luna Park in 1903. They built a War of the Worlds building, put up more than a million lights at the entrance, and re-created an enemy siege on Fort Hamilton. A Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea ride was featured in a third building. Ticket prices ranged from 25¢ for a handful of rides to $1.95 for admission to all rides.

The pool at Steeplechase Park. Library of Congress

In 1908 Thompson, an ingenious man, a predecessor to Walt Disney, re-created the epic battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac, and two years later he built A Trip to Mars by Airplane, where passengers felt like they were flying all the way to Mars. Thompson, like Disney, felt the need to keep his customers amused while they waited in the long lines to ride the rides, hiring clowns and elephants as diversions.

But Thompson spent more than he made, and in 1912 he had to file for bankruptcy. He lost Luna Park to creditors. Barron Collier, the new owner, ran it until it went bankrupt in May of 1933, during the height of the Depression. New owners renovated the park, and it operated until August 12, 1944, when a major fire destroyed most of it. After another fire in May of 1949, the land became the site for a low-income housing development.

Dreamland. Library of Congress

The fourth park, called Dreamland, was founded in 1904 by a politician, William Reynolds, a Republican state senator who had been accused of graft and other chicanery. Reynolds spent $3,500,000 building his park. The rides were mostly copied from other parks. The place had a carnival atmosphere because it was run by a former circus promoter. It boasted a tribute to the armed services, firefighters putting out a large blaze, and Midget City, where some hundred midgets performed at Lilliputian Village.

The Beacon Tower stood 375 feet tall in the middle of a lagoon. A steel pier jutted almost a half mile into the water, so excursion boats could dock. In 1906 Reynolds added a biblical show called The End of the World, in which the good people were seen going off to heaven while the wicked headed for hell.

On May 26, 1911, a disastrous fire erupted and burned the wooden buildings to the ground. There had been ten serious fires before this one. An early-morning fire had burned Steeplechase Park to the ground on July 28, 1907. Owner George Tilyou had no insurance and lost over a million dollars. But this fire was far worse. Workmen were repairing a leak with hot tar at a ride called Hell Gate, when suddenly there was an explosion. By the morning the entire fifteen-acre Dreamland Park was destroyed. The Iron Pier was a smoldering ruin. Little of it was insured. Twenty-five hundred jobs were lost. Reynolds never rebuilt, and the Golden Age of the Coney Island amusement park was over.

Though Coney Island amusement parks continued to operate after World War I, the craze lost some of its allure despite the construction of three of the most famous roller coasters ever to thrill the passengers. In 1925 the huge wooden Thunderbolt roller coaster opened, with its many twists and turns, followed the next year by another huge roller coaster, called the Tornado, and in 1927 by the Cyclone.

Perhaps the amusement-park craze cooled off due to the somber nature of the war. Perhaps it was because the world was becoming more sophisticated and ever more assessible as the automobile made travel easier. The wealthy—and, thanks to Henry Ford, even the middle class—could buy cars and sally forth across America. Air travel would not be far behind. In 1911, the year of the Dreamland fire and a year after the last racetrack was closed, an airplane pilot by the name of Calbraith Rogers took off from the deserted Sheepshead Bay track and flew across the country to Long Beach, California. The first transcontinental flight lasted eighty days, because more often than not, when Rogers landed, he crashed. It would not be too long before planes would make the world a lot smaller.

The aftermath of the Dreamland fire. Library of Congress

Though the amusement-park craze had died down, by the end of the 1920s Coney Island would have more visitors than ever before. The change that swelled the crowds was the opening of the Coney Island beaches to the public in 1923. Until then visitors had to pay one of the amusement parks or a private bathhouse 25¢ during the week or 50¢ on weekends to gain access to the water. After the beaches were taken back by the city, there were Sundays in the late 1920s when more than a million visitors covered the long stretch of sand almost completely with blankets and bodies.

For the teeming immigrant poor who had flooded Brooklyn in a wave during the late nineteenth century, living in a hot apartment during a sweltering summer before the advent of air conditioning, Coney Island became the favorite destination. After the subway system reached Coney Island in 1920, anyone from the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens within walking distance of the subway could pack a lunch and head there for a nickel—or two nickels if you had to transfer between the IRT and the BMT. And if you didn’t have the nickel, you could collect enough glass bottles and turn them in at the local soda shop for a penny a piece, and off you’d go.

If you had an extra nickel, you could buy a hot dog at Nathan’s, which opened on the corner of Surf and Stillwell Avenues in 1916. Nathan was Nathan Handwerker, an employee of Feltman’s, the biggest hot dog seller on Coney Island. When the owner, Charles Feltman, raised the price of his hot dogs to a dime, legend has it that a local singing waiter, Eddie Cantor, and his pianist-accompanyist, Jimmy Durante, were so furious, they loaned Handwerker the $320 he needed to set up his stand to compete with Feltman. Nathan sold his hot dogs for the customary nickel, and it wasn’t long before Nathan’s hot dogs became so popular that the stand became a destination unto itself. Nathan, who apparently also had a good eye for beauty, hired as a waitress Clara Bow, who was discovered, while working there, by a film talent scout. She went to Hollywood and became the “It Girl” of silent-film fame.

Coney Island in the twentieth century drew from Brooklyn’s immigrant melting pot, from the Jews, the Italians, the Irish, the Poles, and the Germans. The various groups came together and harmoniously shared the warm sand and the cool water. For that reason Coney Island—once called “Sodom by the Sea,” while under the thumb of John Y. McKane—would become better known as the “Democracy by the Sea.”