JEWISH OFFSPRING DESPERATELY WANTED TO BLEND INTO THE American tapestry. They competed to be the best, becoming exemplary students, with hundreds of thousands going to college and leading prosperous lives until, by 1976, four out of five Jewish high schoolers were going to college. They were able to prove they were as American as anyone else by becoming involved with the local baseball teams—in New York City it was the Dodgers, or, for the rebels, the Giants and the Yankees. Because of the constant threat of persecution that hung over their heads, they held a deep interest in politics and social justice. Despite President Roosevelt’s passivity about saving the European Jews from the Holocaust, his economic policies that helped bring the nation back from the Depression made him the overwhelming choice of Brooklyn’s Jews.

Israel “Sy” Dresner, who would go on to become a rabbi and a figure in the civil rights movement, moved to Brooklyn from the Bronx in 1930, when he was a year old. He grew up in Borough Park, which, during his childhood, he says, was “one hundred percent Jewish.” Until he went to New Utrecht High School, Dresner’s view of the world, like Ira Glasser’s, was ethnocentric. Up to age fifteen, he had met exactly one black person, and very few non-Jews. After he went to high school, he thought the rest of the population was Catholic, because half his high school was Jewish, half Italian. Living in Brooklyn, he didn’t know Protestants even existed.

SY DRESNER “I was born on April 22, 1929, six months before the beginning of the Depression. Whenever my mother would get angry at me as a little kid—and as a little kid I was a tsatzkala—she would yell at me in Yiddish and blame me for the Depression, because it was a clear case of cause and effect.

“When she was seven years old, in 1913, my mother came from what Jewish history books refer to as Congress Poland, what Americans refer to as Russian Poland. It was the Poland of the czarist empire, a shtetl of about six thousand people called Austrovitz. Shtot in Yiddish means ‘city,’ and el in Yiddish means ‘little,’ so a shtetl is a little city, or a town. Until I was ten, I thought she was born in America, because she lied to me. You could not tell she was born abroad. She had a thick New York accent.

“My father, who was born in 1898, was twenty-one when he came to America from East Galicia, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. My father was born in a place that was smaller than a shtetl, what in Yiddish is called a dorfel. Dorf means ‘village,’ and el in Yiddish means ‘little,’ so a dorfel is a hamlet. My father’s hamlet had nine hundred people, all Jewish, about a hundred who were related to him.

“My father’s older brother Lazar, Uncle Louie, came to America in 1913, and my father would have come earlier, except for the breakout of World War I in 1914. The czarist Russian army captured the hamlet in late August of 1914, the first month of the war. Illiterate peasants made up the army, and many of them had no contact with Jews because Jews were prohibited from living in most of Russia. When the army captured a Jewish town, there would be semispontaneous pillaging, looting, and raping. These pogroms occurred hundreds of times as regions of Galicia and Bucovina fell.

“My father’s sister, who was sixteen and a half, was raped by a Russian soldier, and she went into shock. There were no doctors, and she died the next day. The entire hamlet fled into the interior of the Hapsburg Empire, as did a half a million other Galicianer Jews. My father’s family got within twelve and a half miles of Krakow, and they all wound up in a refugee camp in what today is Bohemia in the Czech Republic. After spending two and a half years there, he was drafted into the Austrian kaiser’s [Franz Joseph—not to be confused with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany] army.

“Most people don’t know that, for the Jews, World War I was a disaster. Jews fought on both sides. More than half a million Jews lost their lives in World War I.

“My father was wounded on the Russian front. He was hit by shrapnel. He was sewed up badly, and thirty years later you could still see the bad stitches in his forehead. But it was lucky for him, because it got him out of the war.

“My parents met in America. It was an arranged marriage. When my father came in 1921, he was already close to twenty-nine, which was considered very old for a bachelor. He went to work for Uncle Louie, who had been in America eight years and owned a bar and grill on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. It was part of Yorkville, a German neighborhood. East 86th Street was lined with one oompah-band restaurant after another.

“My father had no education to speak of, not even a Jewish education, but he had a very high IQ.

“My mother didn’t have much education either. She went for one year to Washington Irving High School in Manhattan, and then she dropped out. Her best friend was the daughter of Margareten, from Horowitz Margareten, a company that makes matzo and matzo meal, and my mother got a job in the factory when she was fifteen.

“They had two weddings, a civil wedding in New York, and a religious wedding in Montreal, because the Montreal part of the family couldn’t leave Canada because they weren’t Canadian citizens yet. They had come to America after 1924, after the second National Origins Act. The law was designed to keep out inferior people from Southern and Eastern Europe—Jews, Poles, Italians, Lithuanians, Czechs, Slovenes, etc.—from entering the United States, and if it hadn’t been for those laws, a lot more Jews would have survived World War II, saved just by normal immigration.

“My parents were living in Yorkville with my uncle, and when I was six months old, they moved to the Bronx. The Depression had started, and in April 1930 my uncle kicked my father out of the bar and grill because things were already doing very badly.

“Six months later my uncle did help him get a deli in Brooklyn, in Flatbush, between Parkside Avenue and Ocean Avenue, and we moved to a little four-story building at 188 Parkside Avenue, about ten stores down from the deli, which was called Dresner’s.

“It was a goyishe deli, a traif deli, because it was not in a Jewish neighborhood. My father had all sorts of terrible things in it, like liverwurst, pork, and ham, and we were not allowed to eat in the store because our home was kosher. On occasion, my father would slip me a cream cheese sandwich on a kaiser roll. He would make me swear not to tell my mother, who was super-kosher.

“My father became an American because of baseball. When he first came to this country in 1921, the team in New York was the Giants. The Yankees had not yet won a single pennant. The Dodgers had won two pennants, in 1916 and 1920, but lost in the World Series. By 1921 the Giants had already won six pennants.

“When my father worked for his brother in Manhattan, he would go to the Polo Grounds all the time. He got to know the game really well. He loved the game, and the only sports activity he ever did with me was to take me to the Parade Grounds, about a three-block walk from where we lived, to play catch.

“He had this phenomenal memory for numbers. He knew all the batting averages.

“In 1927 he went for his citizenship papers. He had been in the country six and a half years. My father got all dressed up with a bowler hat, a tie, a white shirt, and a suit, and he had to take a test on American history.

“To study for it, my father went to night school for exactly one session. He fell asleep during class because he worked a twelve-hour day. He never went back. He didn’t know from nothing about American history.

“‘How many states in America, Mr. Dresner?’ My father answered, ‘Eighteen,’ which for Jews is a lucky number.

“‘Who was the first president?’ ‘Warren Harding.’ My father liked him, because his middle name was Gamaliel, a Talmudic rabbi.

“‘What is the capital of the United States?’

“‘New York.’

“My father got all the answers wrong, and every time he answered, he would take out his pocket watch and look at it. Finally, the interrogator said to my father, ‘Mr. Dresner, why are you looking at your watch every two minutes? You’ve been waiting to become an American citizen six years. We can keep you waiting much longer.’

“My father, in his Yiddish accent, said, ‘Your Honor, I don’t mean to be disrespectful in any vey, but dese questions and answers are going on so long. In honor of my becoming an American citizen, I bought two tickets to the Giants-Cubs doubleheader at the Polo Grounds, and if you keep asking me dese kvestions, I’m going to miss most of the first game already, and the Giants are only two games behind. If they win the doubleheader and the Cardinals lose a doubleheader, they’ll be tied for first place.’

Casey Stengel, left, managed the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1934 to 1936.

AP Photo

“At this point, the interrogator said, ‘Mr. Dresner, you are a true American in every way, a lover of baseball, the national pastime. Citizenship granted.’ It was a story my father told many times.

“After we moved to Flatbush, we would go to Ebbets Field maybe thirty games a year. Across the street from Dresner’s was a big apartment building, six stories high, with an elevator, and the entire Brooklyn Dodger baseball team lived there, and they all ate at Dresner’s. In 1933 I sat on Casey Stengel’s lap. He was the manager. Babe Herman used to come in to eat all the time.

“We would get free tickets to any game we wanted, because the Dodgers were a terrible team. It was the ‘Wait ’Til Next Year’ era. They would inevitably finish in seventh or eighth.

“There was no night baseball, so the games started at three P.M. The games were quick. They were over in an hour and fifty minutes. You didn’t have long commercial breaks between innings. There was no advertising, no television. You didn’t have eight pitchers come into a game. A guy would start, and he’d finish.

“If it was a slow day and there wasn’t much business, my father would close up the store at around two thirty P.M. He’d sweep up in five minutes, go to the front door, and switch the sign from OPEN TO CLOSED, and he’d lock the door.

“We would walk half a block to Flatbush Avenue and get on the streetcar. It was a nickel, and I was free because I was four years old. We’d go down to Empire Boulevard, alongside Prospect Park, and we’d get off and walk to Bedford Avenue and into Ebbets Field.

“We had free tickets, and it was almost like I was the mascot of the team. I even got into the dugout a couple of times. I knew all the Dodgers. They had a pitcher by the name of Van Lingle Mungo, who became famous because of a pop song by that name many years later. We had Luke ‘Hot Potato’ Hamlin. They had wonderful monikers for the players back then. I became a real maven in baseball.

“Still, we were Giants fans. I was four and a half in 1933 when my father took me to my first World Series against the Washington Senators. I was about seven when I learned to read my first box score, and I celebrated in 1936 when the Giants won the pennant again.

“My dad and I used to sit down the right field line right near the Giants’ bullpen in the Polo Grounds. My father sat there because he liked the second-string catcher named Harry Danning. Harry was Jewish, and he and my father would schmooze in Yiddish all the time to each other.

“I was a yeshiva bucher. I didn’t go to public elementary school. I started attending in 1935, and took the Thirteenth Avenue bus to get there. The first day my mother went with me, and after that I went by myself. I was five years, nine months old. She talked to the driver, who told her he’d be driving every day, and he promised to make sure I got off at the right stop.

“After a year at the yeshiva, my parents decided we would move closer to the school. Moving day was June 30, and we moved to Borough Park so I could walk to school. It was 1935, the middle of the Depression.

“My mother read the Daily News every day. The News was owned by Cissy Patterson, the sister of the owner of the Chicago Tribune, and it was anti-Roosevelt, anti–New Deal, and pro-Republican, but my mother didn’t read the editorial page, and neither did most of the other 2 million readers, because my mother and most of the people who read the Daily News voted for Roosevelt. So did my father, who every day read a Yiddish newspaper Der Tog, a middle-class, pro-Zionist daily.

“Roosevelt came in on March 4, 1933, and he was reelected in a landslide. In 1936 he won every state but Maine and Vermont. There was a famous expression, ‘As Maine votes, so votes the nation,’ but at a victory dinner a couple weeks later, Jim Farley, the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, got up and said, ‘As Maine goes, so goes Vermont.’

“My dad went bust in 1937. The New Deal improved employment greatly, but in 1937 there was the Roosevelt recession, and my father had huge debts, of around $2,800. He refused to go bankrupt, and it took him until 1944 to pay everyone off. He went to work for one of his distributors, Kings Beverages, delivering soda and soda water on commission.

“My father had to learn to drive, because the company gave him an old Model A with two doors and a rumble seat, and my mother wouldn’t get into it during the daytime, because on each side was painted in white letters KINGS BEVERAGES, and she was embarrassed.

“I never went to camp during the summer, not once. Growing up, I never saw a Broadway play, though my dad would take me to Yiddish theater. Through reading the Daily News and the paper P.M., I developed a keen interest in politics.

“The first election I was really involved in was the Roosevelt–Wendell Wilkie race in 1940. I read the Daily News every day, and in September they had a poll of various counties in New York State. It was a primitive poll. What they didn’t understand was that people change their minds. By Yom Kippur, Wilkie was leading in the polls, and my father was distraught. My father was in such a state of depression, he was sitting in shul, glum. He and this old man with a white beard were talking in Yiddish, and my father was really depressed, and they were talking about the election, and my father said in Yiddish, ‘Even the Jews are voting for Wilkie.’ And the old man looked at my father, and he said in Yiddish, ‘Don’t worry. A Jew lives in drei velt, three worlds. He lives in di velt, this world. He lives in yenna velt, the other world, and he lives in Roose-velt.’ My father started laughing, and it really did snap him out of his funk.

“And in 1940 Roosevelt ended up with 90 percent of the Jewish vote, and of course he won easily. It was normal, if you were Jewish, to be liberal. Jews were still poor, many were immigrants, and Jews were an oppressed group, the most oppressed group in the world.

FDR and Mayor LaGuardia . Library of Congress

“The country had a lot of anti-Semites in it. It was very prevalent in 1940. I was fully aware of the anti-Semitism of Father Coughlin and Henry Ford.

“I went to the yeshiva as far as the ninth grade. I had a scholarship to continue in the high school department of Yeshiva University, which was up in Washington Heights, but beginning two years before that, I had gone into rebellion against Orthodoxy, and I refused to go. I became an atheist. I was a smart fourteen-year-old kid who knows everything.

“I’ve always had a big mouth. I started studying Talmud when I was nine. They had a special class for smart kids, an hour a day with Rabbi Binimovich, an old man with a white beard, who had been the disciple of one of the great Talmudic scholars in Lithuania. As I got older, I started asking the wrong questions, and sometimes I would get a slap in the face.

“Say we were studying the kosher laws. I would say, ‘When the three angels visited Abraham in the book of Genesis, Abraham served them milk and meat at the same time. How was it Abraham, the founder of our faith, was not kosher?’ It was a provocative, subversive question, and Binimovich, who was no dope, knew it, and he slapped me across the face, and I was tired of it.

“Part of my dissatisfaction with Orthodoxy was not knowing there was any other kind of Judaism. It was not until after the World War II that the Conservative and Reform movements became popular. Jews between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five in the army came into contact with Jewish chaplains, who were 99.3 percent Reform or Conservative, because the Orthodox were not able to serve in the army. They couldn’t eat the food, because they were kosher, or they didn’t know enough English, so all the Jewish chaplains were Reform or Conservative, and when these guys got out of the army in 1945 or 1946, they founded Reform or Conservative synagogues. They became the two massive movements in Jewish-American life.

“So I was getting slapped for asking the wrong questions, and Hitler and the war also were on my mind. It was October of 1942, and it looked like the Axis was going to win the war. The Wehrmacht was at the gates of Stalingrad. The Japanese had overrun everything under the sun, conquering the Philippines, Malaysia, the Dutch East Indies, most of New Guinea, and Burma. The American Navy had been destroyed at Pearl Harbor. The Germans had captured one country after another in Europe. We didn’t know yet about the Holocaust, but we did know things were going very badly for the Jews. So I had all sorts of reasons for becoming an atheist. Plus I wanted to be sophisticated, advanced, modern.

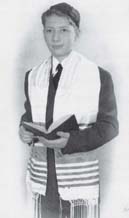

Sy Dressner. Courtesy of Sy Dressner

“I had a friend, Gabey Bloom, with me at the yeshiva. His father had served in the Jewish Legions in World War I. It was a special unit the British had created, open only for Jews. General Allenby was the commander of their Middle East army fighting in Palestine. Gabey was richer than we were. He had a house with a porch, and he joined a Zionist group called Habonim, the Labor Zionist Youth Movement, that urged Jewish kids to go to Israel and live on a kibbutz, and because of Gabey, I joined as well.

“I entered public school in the tenth grade, in Brooklyn, at New Utrecht High School. Utrecht is a Dutch name. The New York City flag has orange in it, and the orange is for the House of Orange from the Dutch days. I became the sports editor of the New Utrecht High School weekly paper, which was known as the NUHS [pronounced “news”]—we were very clever.

“New Utrecht had a great track team. We used to get into the finals every year in the old Madison Square Garden on 48th Street, where we always lost to a Catholic school called Bishop Laughlin. It was the only thing we were good at. Erasmus, our great enemy, would beat the shit out of us all the time in basketball and football.

“New Utrecht was half-Jewish and half-Italian. The school was in an Italian neighborhood, and we got to it on the BMT line. We got off at the 79th Street stop and walked half a block to the high school. Even though we were as numerous as they were, they controlled the neighborhood, so we had to watch our Ps and Qs, otherwise we’d get the shit beat out of us. We had family members of the Mafia in the school. Albert Anastasia was a famous mobster who was gunned down in a barbershop. An Anastasia kid was in my class.

“I ran for president of the GO, the student government. It was the war years, 1944, and there was a morning session that started at seven thirty and ended at noon, and an afternoon session that began at eleven and ended at three thirty. I ran against a kid named Delvecchio, and when the morning results came in, I was leading by 387 votes, and everyone was congratulating me. The girls were kissing me, and then the afternoon results started to come in, and my majority kept falling, and I lost by 6 votes.

“The morning session was juniors and seniors, which was overwhelmingly Jewish, because a lot of the Italian kids had dropped out to go to work or to join the army. The freshman and sophomore classes had a lot more Italians in them, and by the end of the day Delvecchio had more votes than we did. It was a clear-cut case of ethnic politics.”