IF THERE WAS A GROUP THE CHRISTIAN CONSERVATIVES HATED more than the Jews, it was the African-Americans or blacks—or, as they were called in the South before the civil rights movement made people watch their tongues, the niggers. They started out as slaves, captured in Africa and brought to America half-dead in the hold of fetid ships. They were sold as chattel in the slave markets of southern cities like New Orleans, Atlanta, Montgomery, and Savannah to Christian plantation owners, and northern ones like New York City and Boston to merchants and households as well as to farmers. Black families were split up, the individuals forced to work for their white masters for no money.

Early on, the liberals in the North wanted to end slavery, but the southern Christian conservatives, including Founding Fathers Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe, were resolute in their desire to continue the practice. They felt the economic viability of their large plantations depended on it.

To back up the legitimacy of what they were doing, churchgoing slaveholders could quote Bible passages chapter and verse. The primary passage had to do with Noah and his three sons, whose descendants repopulated the earth. According to the way the Bible was interpreted, after the flood, Noah’s son Ham, whose descendants were black Hamites, was cursed. Says the Bible, “Noah cursed Ham to be a slave to his brethren Japheth.”

Since Japheth’s lineage goes through Europe and the Caucasus Mountains, the interpreters of the Bible concluded that God meant for Ham’s descendants to be slaves.

It’s hard to imagine a person using religion to justify keeping another human being in bondage, but for hundreds of years the Christian right not only used their religion to justify slavery—after it was abolished, they used it to justify segregation.

It took a civil war, of course, to end the practice of slavery in America, and for more than two decades the North administered the southern states, allowing blacks to vote in over a hundred of their kind to the legislatures of North and South Carolina alone.

Then, in 1876, the nation’s centennial election was held. Neither of the presidential candidates—Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden—had the votes to win. Hayes’s people made Tilden’s people an offer he couldn’t refuse: if you throw your electoral college votes my way, I will withdraw the northern army from the three southern states still being occupied by northern troops: Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Tilden agreed. Hayes became president, and for the first time since the end of the Civil War, the South completely controlled its future.

Immediately, the Southerners in those states did what the Southerners did in the other states after the withdrawal of federal troops: they threw out all the blacks that had been elected to office, and they passed laws making sure they would never return. Since slavery had been abolished by the Constitution, they could only do the next best thing: pass laws to make sure blacks ended up as badly off as when they were slaves.

As part of these Jim Crow laws, blacks were effectively banished from white society. They weren’t allowed to eat in the same restaurants as whites, stay at the same hotels as whites, shop in the same stores as whites. They had to use separate bathroom facilities, go to separate schools—if blacks were allowed to go to school at all—drink from separate drinking fountains, and ride in separate train cars. Some cities even designated where blacks could and could not live and shop.

The poor white Southerners didn’t know it, but they were being sold a bill of goods by the Southern aristocrats. No matter how badly off they were, they were told, they were still in better shape than the Negro.

Ku Klux Klan rally. Library of Congress

To make sure the Negroes kept their place, an organization called the Ku Klux Klan was founded. It was begun right after the Civil War by six former Confederate soldiers in Pulaski, Tennessee. The name kuklux was a form of kuklos, the Greek word for circle. These men rode horses through the countryside while draped in white sheets and pillowcase hoods. It wasn’t long before it evolved into a multistate terrorist organization designed to frighten and kill emancipated slaves using lynching, shooting, burning, castration, pistol-whipping, and other forms of intimidation.

Membership in the Klan was restricted to those who believed in the strict interpretation of the Protestant Bible. To join, you had to swear that you believed in three Christian principles: the virgin birth of Jesus; the literal infallibility of the Bible; and the bodily resurrection of Christ. To enforce the notion that the Klan was a terrorist group fighting in the name of Christianity, it chose as its symbol the cross, and when it wished to show its power, the Klansmen would burn a large cross on the property of those they wished to intimidate. They were an army likened to crusaders, only their targets weren’t the infidels but rather fellow Americans of the Catholic, Jewish, and black persuasion.

A primary task of the Klan was keeping blacks in their place.

In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant went before the House and spelled out the aims of the Klan: “By force and terror, to prevent all political action not in accord with the views of the members, to deprive colored citizens of the right to bear arms and of the right of a free ballot, to suppress the schools in which colored children are taught, and to reduce the colored people to a condition closely allied to that of slavery.” Through legal and military intervention, Grant seriously curtailed the Klan. After Hayes took office in 1877, it was once again free to roam the land in support of the white race.

Whites in the South between 1890 and 1910 did everything to make sure black leaders who spoke out against Jim Crow were silenced. Ida Wells was run out of Memphis for her outspoken opposition to lynching. After race riots in Atlanta in 1906, Jesse Max Barber, editor of Voice of the Negro, was given three choices: leave town, recant his opinions on the causes of the riots (that it was the whites’ fault), or serve on a chain gang. He fled to Chicago.

What brought about a renewed resurgence of Ku Klux Klan activity was the movie The Birth of a Nation, which exploded onto the scene in 1915. In an age in which most movies cost a nickel, this one cost two dollars, and the lines stretched around the block in every city in which it appeared. More than 25 million tickets were sold.

Written and directed by D. W. Griffith, the movie portrayed the Klan as the protectors of America. Blacks during Reconstruction were the villains of the piece. Thomas Dixon, who wrote the novel upon which the film was based, went to visit President Woodrow Wilson, his college classmate. Wilson, a Virginian who had segregated the formerly integrated federal bureaucracy, said, “At last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.” He also is reported to have said about the movie, “My only regret is that it is all so terribly true.” Wilson’s feelings about Jews were so open and notorious that Eugene Debs, writing in the Dearborn Independent, called the president “the nation’s premier anti-Semite.”

A few days before the film opened in Atlanta, Colonel William Joseph Simmons climbed Stone Mountain, burned a cross, and announced the rebirth of the Klan. The Klan’s message combined hyper-patriotism and moralistic Christianity with the disdain for elites, cities, and intellectuals, and a hatred for blacks, Jews, Catholics, and foreigners. By 1920 the Klan had 8 million members.

LeRoy Percy, a U.S. senator and a large landholder in the Mississippi Delta, who defeated the Klan in a local election in 1923 on a platform of decency, fairness, and humanity, blamed the Protestant Church for its proliferation. He wrote: “No class of American citizenship can escape responsibility to its duty as the protestant ministry. The repudiation of this sulking, cowardly, un-American, un Christian organization as the champion [of] Protestantism should have been instantaneous and wide spread and such a repudiation would have sounded its death knell…[but] the rank and file of the Baptist and Methodist ministry has either acquiesced in it or actively espoused it.”

According to the Klan, the world was falling apart, but the Klan would make things right. Out of fear, the Klan enforced a conformity of hate. It was “us” against “them.”

As John Barry described it, “The ‘them’ has often included not only an enemy above but also an enemy below. The enemy above was whoever was viewed as the boss…Wall Street, or Jews, or Washington; in the 1920s the enemy below was Catholics, immigrants, blacks, and political radicals.”

Little had changed in the country by the 1940s. Both the Republicans and the Democrats were deathly afraid of losing the Southern bloc, so neither party dared voice any objection to the status quo. The people who were brazen enough to take up the cause of the Negro were mostly white, immigrant Jews—members of the Communist Party, which in 1924 proclaimed that “the Negro workers of this country are exploited and oppressed more ruthlessly than any other group.” Negroes, with few exceptions, did not campaign to end Jim Crow. It was too dangerous. They could be tarred and feathered, or lynched. The Jews who suffered such treatment under the czar sympathized, and they banded together to see if they could help their black brethren get a fairer shake in American society.

In 1928 the Communist Party made twelve demands to end black oppression. One of them was ending race discrimination. Full social equality was another. Because the Palmer Raids and the Red Scare had been successful in marginalizing the Communists, few right-thinking Americans paid any attention. (Forty years later, segregationists in Congress read the Communist Party’s platform into the Congressional Record in an attempt to undermine civil rights reform.)

That same year the Communist Party attempted to organize in Harlem. Their candidate was Richard Moore. The Communists had so little sway with the black community that Moore garnered exactly 296 votes.

In the 1930s there were two major trials that resulted in such obvious injustice against black defendants—the Scottsboro Boys and later Angelo Herndon—that America was embarrassed by public opinion around the world. The Scottsboro case marked the emergence of the Communist Party in Harlem more than any other event.

In that case, a group of twelve black boys riding a freight train were accused of driving a group of white boys off the train and then attacking two white girls. One of the girls cried rape and pointed out her attackers. The problem was that when the girls arrived at the station, they never said anything about being attacked. Doctors who examined them said that though the girls had had sex, they had seen no signs of injury or struggle. It was only after a group of vigilantes arrived to avenge the attack by the black youths on the white boys that the girls made their rape charges. The National Guard had to be called to prevent a lynching. The Communist Party made the Scottsboro case the focus of its antilynching campaign. The prosecutor announced he was seeking the death penalty for all the defendants. In his summation, the prosecutor said to the jury, “Show them that Alabama justice cannot be bought and sold with Jew money from New York…”

It didn’t take long for the jury to agree to put the first defendant, Haywood Patterson, to death despite the lack of evidence. It was surely a legal lynching. Communist lawyers handled the appeal. When the Supreme Court agreed to hear the appeal, the legitimacy of the Communist Party in America greatly increased.

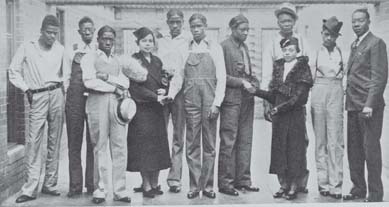

The Scottsboro Boys. Library of Congress

The Communist Party led a powerful march on Washington on May 6, 1933. That month, Harlem congressman Adam Clayton Powell threw his support to the Communists. He said, “The day will come when being called a Communist will be the highest honor that can be paid an individual and that day is coming soon.” In June of 1933 the jury verdict in the Patterson case was overturned, and a new trial ordered.

The next big case was that of Angelo Herndon, who was prosecuted because he was black, a union activist, and a member of the Communist Party. His father had died from “miner’s pneumonia” when Angelo was nine. He saw that segregation was used by the Lexington, Alabama, mine in which he worked as a “cunning” device to keep the union out, and at seventeen he became a recruiter for the National Miners’ Union. When members of the Communist Party came to talk to them, he was impressed.

“They believed that Negroes ought to have equal rights with whites. It all sounded okay to me…” he said.

In 1932, at age nineteen, he traveled from Cincinnati to Atlanta to become an organizer for the Communist-led Unemployed Council, mobilizing jobless workers, their wives, and children, who were literally starving to death while the Georgia authorities did nothing. Herndon was attempting to get the County Commissioners of Atlanta to pay $6,000 to whites and blacks for unemployment relief when he was arrested without a warrant by the Atlanta police on charges of being a vagrant and of “attempting to incite negroes [sic] to insurrection.” The law he was accused of breaking was first passed in 1861, through the influence of slaveholders who were scared that their slaves might revolt after listening to Northern antislavery propaganda. The only penalty under the statute was death. The law was revised in 1871 to include all incitement to insurrection. No mention, of course, was made of slaves. It was aimed at the carpetbaggers who had taken over the South’s governments. Herndon was never charged with any specific act. His crimes included attending public assemblies, persuading people to join the Communist Party, and circulating Communist literature.

Herndon was held in jail for six months. The fact that he had organized whites and blacks together was what really riled the racists in the prosecutor’s office. The prosecutor sought the death penalty.

During his six months in jail awaiting trial, he was systematically starved.

He was represented at trial by Ben Davis, a black Harvard Law graduate and a member of the Communist Party, and a young white Atlanta lawyer by the name of A. W. Morrison. At trial the prosecutor told the jury, “This is not only a trial of Herndon, but of Lenin, Stalin, Trotsky, and Kerensky. As fast as the Communists come here we shall indict them and I shall demand the death penalty in every case.”

Said the prosecutor about Herndon’s championing of equal rights for blacks: “Stamp this thing out with a conviction.” He asked for the death penalty, but the jury was “lenient” and he was sentenced to eighteen to twenty years on the chain gang.

The prosecution witnesses constantly referred to Herndon and other blacks as “niggers” and “darkies,” over the objection of the defense. The judge clearly was hostile to Herndon. The literature in Herndon’s room had been seized without a search warrant, but the judge allowed it into evidence anyway.

Because of the national and international publicity of the case, Atlanta suffered a black eye in the court of public opinion, and Herndon was released after a year in jail. He was greeted by six thousand supporters when he arrived by train from Georgia at New York’s Pennsylvania Station.

In the 1930s many college students were looking to understand the Depression and why it happened, and because of the vacuum left by the Republican and Democratic Parties, which had no answers to explain why capitalism had failed them, they joined the CP’s Southern Negro Youth Congress, another organization dedicated to civil rights and to the rights of workers to unionize. The Southern Negro Youth Congress supported the CIO’s blue-collar organizing, established campus cooperatives and student labor unions, and campaigned against segregation in college area stores, services, recreational facilities, athletic teams, and in university admissions. It also sought to battle Jim Crow in the South.

The organization gained in strength until August of 1939, when Stalin entered into a pact with Hitler and Nazi Germany. When this happened, American Communists were left demoralized and confused. Nazi Germany had been the enemy. Fighting fascism always had been the primary goal. At the end of September of 1939, the Comintern ordered the American Communists to change their target—they were ordered to attack President Roosevelt so as to keep America out of the war. Some Communist leaders did this, which put them on the same side as the America Firsters like Joe Kennedy and Charles Lindbergh. A few American Communists went along, but most members became disgusted and dropped their membership. By 1940 the student movement in the Communist Party was about over. By the end of World War II, the CP had very little influence left. Russia was no longer an ally, and overnight it had become the enemy that had stolen our secrets and threatened our way of life. When the reprisals came, it was open season on anyone who had ever been a member of the party or one of its many organizations.

The civil rights work done by the Southern Negro Youth Congress, however, should not be forgotten. It was among the very first organized efforts to do something about Jim Crow. It was also part of the campaign to force major league baseball to hire a black player.

Dorothy Challenor, who was born in 1915, was one of the pioneers of that movement. She grew up in Clinton Hill, a small neighborhood in north-central Brooklyn. East of Bedford-Stuyvesant, it was a community where blacks and whites lived in interracial harmony. A block from where Challenor lived, stately mansions lined Clinton Avenue, home of millionaires’ row. Challenor’s dad was a janitor and her mom cleaned houses for whites, but she never let her lack of means deter her from getting an education. When she began attending Brooklyn College in the mid-1930s, she met influential teachers who led her on a path of trying to change the world.

After the public trials of the Scottsboro Boys in 1931 and Angelo Herndon in 1932, Challenor became aware of how much worse Southern blacks had it than she did. She and fellow Brooklyn College students Edward and Augusta Strong helped form an organization called The American Youth Congress, a group dedicated to social justice and racial equality. After driving to New Orleans in 1938 to attend a conference of another group dedicated to civil rights, the Southern Negro Youth Congress, Dorothy learned firsthand the trials of traveling in the South while black.

Dorothy met and married Louis Burnham, and for the next seven years the two would live in Birmingham, Alabama, working with the unions of black steelworkers and black coal workers to pressure Southern political leaders to repeal the poll tax. When black veterans returned from World War II, she organized them to increase the pressure to repeal the oppressive measure. Alas, despite their efforts, Southern resistance remained steadfast.

One white who was moved by their efforts was Eleanor Roosevelt, who saw how hard the poor—and poor blacks in particular—were struggling to get a fair shake, and it is fair to suggest that planks of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal came directly from the yearnings expressed by groups such as the Southern Negro Youth Congress. As a result, federal laws were passed preventing discrimination in housing and health care, and it was under Roosevelt that laws were passed calling for a minimum wage, social security, and the end of job discrimination.

By 1940, the establishment was ready to fight back, and it did so with a vengeance, under the Smith Act, which decreed that anyone who willfully advocates the overthrow of the U.S. government shall be imprisoned or fined. The bill was sponsored by Representative Howard W. Smith of Virginia, a racist Democrat who supported the poll tax and was a leader of the antilabor bloc of Congress. The bill was signed by President Roosevelt. What Roosevelt did not anticipate was that all prosecutors had to do was charge a defendant with being a Communist and then cite Karl Marx’s desire to overthrow the government. The argument would be made that if Marx wanted revolution, then so did the defendant. Dozens of those charged under the Smith Act, who had done nothing but push for civil rights, social justice, or unions, were convicted. Worse, anyone accused of being a Communist was stained as being a traitor, when the truth was that many of the defendants were just the opposite: fighters for freedom, and lovers of a just America. The Supreme Court in 1957 would declare many convictions under the Smith Act unconstitutional. The smear campaign that was the hallmark of the 1950s McCarthy era also meant that anyone branded a “Communist” would disappear from history, no matter how important his or her work in helping to create a better world for workers, blacks, or the poor.

By 1953, the Southern Negro Youth Congress was out of business, as organizers were arrested, their families harassed, and donations dropped precipitously. Dorothy and Louis Burnham moved to Harlem, where he and Paul Robeson started Freedom magazine. Robeson, who was blacklisted and couldn’t work, moved to Europe. Louis and Dorothy Burnham together continued their work until Louis’s death in 1960. The saintly Dorothy Burnham, now ninety-three, who risked life and limb so that African-Americans could live in freedom, resides in anonymity in Brooklyn, still hoping for better days for the working class.

DOROTHY BURNHAM “My father was a shoemaker who grew up in Barbados, but the shoemakers’ union in Brooklyn kept him from working at his trade because of racism, and so he became a janitor. He did work at the I. Miller shoe company off and on, but he was steadily employed as a janitor. My mother was a house worker and a factory worker.

“I grew up in the Clinton Hill area of Brooklyn. When I was growing up, the neighborhood was integrated. There were fairly well-off people living there, so the schools were good. I went to PS 11, and then I went to Girls High School on Nostrand Avenue. I had white friends and black friends. There was no obvious discrimination at school that I remember, though there were no black teachers in either elementary or high school, and sometimes the white kids were treated a little bit better than the black children. But it wasn’t obvious.

“My mother knew one black teacher. My sister and some of her friends went to the Maxwell Training School for teachers, and there were two or three blacks in her class, and they didn’t let them pass the oral exam because they spoke with a Southern accent, so there was discrimination in that way. When my sister graduated, it took her a while before she got a job teaching, but she finally did get a job.

“The segregation wasn’t open, but the real estate companies wouldn’t sell houses to black people in white neighborhoods in Brooklyn. There were expansive mansions on Clinton Avenue, a block from our apartment, and that was limited to white people. There were no blacks at all living on many streets. In 1935, when I was twenty, I remember a friend was married to a white man, and he went and got an apartment, and when they moved in, there was a big hullabaloo about it. We organized, and they had to let them stay, but right after that that apartment house became mostly black, because the white people started moving out.

“A number of the restaurants in Brooklyn wouldn’t serve blacks, so there were places we couldn’t go. One we could go into was Horn and Hardart. You put nickels in the slots and took your food. It was like the McDonald’s of its day.

“I went to Brooklyn College because it was free. The average to get in was in the eighties, and my grades were good enough, and at that time there was a very small minority of black students. There were two or three black girls in my class, and we got together and organized a group and met fairly regularly. It was an opportunity for us to get together and talk.

“At Brooklyn College I met some teachers who were very much interested in changing the world. They were socialists and communists, and they talked about discrimination and poverty, and they explained what we had to do to end it, and they gave us reading materials, made me interested in changing the world.

“I learned about the Angelo Herndon case and what happened to him. And then there were the Scottsboro Boys, who were falsely accused of rape. There was a black woman a year ahead of me in school who started organizing support for the Scottsboro Boys. And then she introduced me to other people in the movement. The Scottsboro case made me understand the racism that was going on in the South. What moved me most into the movement was my hearing about the discrimination and the lynching of blacks in the South.”

While Dorothy was studying at Brooklyn College, in 1936 her friends Edward and Augusta Strong organized a civil rights group called The American Youth Congress, and another friend, James Jackson, organized another civil rights group that called themselves the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC). A year later Dorothy was invited to attend SNYC’s second annual national meeting in New Orleans.

DOROTHY BURNHAM “I was living in Brooklyn at the time, and I and several friends of mine in the movement drove to New Orleans for the conference. It was the first time I had traveled South, the first time I saw open discrimination. I just remember we had to be very careful where we stopped. We could only stay at the black YWCAs or YMCAs. In Brooklyn there was a white YWCA and a separate black YWCA. The pool was at the white YWCA, and we could only swim in it once a week. Once we got South, we had to find the few black restaurants along the way.”

In 1940 Dorothy met Louis Burnham, an active member of the American Youth Congress and of the student movement at City College. He was a fiery orator on the street corners of Harlem, a man dedicated to ending discrimination wherever he saw it. They married in Brooklyn in 1941, just before he was asked to move to Birmingham, Alabama.

DOROTHY BURNHAM “Louie ran for assemblyman on the Labor Party ticket. He talked mostly about discrimination, racism, and opportunities for working-class people. He attended a lot of street-corner meetings, and he would speak around Lenox Avenue, Seventh Avenue. In 1941 he was invited to replace Ed Strong as the executive secretary of the Southern Negro Youth Congress. Their primary task: getting blacks the vote.

“The poll tax was one of the ways the whites were able to keep people from voting, especially blacks, and there was resistance to what we were doing, because they wanted to exclude blacks from making decisions about what happened with their lives. Blacks couldn’t vote, and as part of our campaign we fought for equal opportunity and the right to vote in a democracy.

“We would get letters from people threatening the offices of our organization. ‘Stay away.’ I don’t remember actual threats to our lives. We were especially active getting the black coal miners and steel workers to help us organize in our fight to end the poll tax.

“It was a big struggle. I don’t think they ever did do away with it. At that point they weren’t quite ready, but it was the beginnings of the struggle in the South. And when the black soldiers came back from the war, Henry Mayfield tried to organize the veterans, but that didn’t work either. The cops would push people away from campaigning or walking the picket lines. They’d come and arrest us.

“One of our members, Mildred McAdory, got on a bus one day, and she refused to move to the back of the bus—that was long before Rosa Parks—and they arrested her. When Rosa did it, there was enough backing to mount a campaign for her, thank goodness. They took Mildred off to jail, and we had to pay a fine, and they released her. She didn’t have to serve any jail time. But her actions didn’t have any further repercussions either.

“My husband, Louie, was eating in a restaurant with three white teachers from Talladega one time. It was a black restaurant, and occasionally whites would come over and eat in a black restaurant, but this time somebody gave the signal, because they were Southern Negro Youth Congress people, and the cops were alerted and arrested the four of them for eating together in a restaurant and took them to jail. They spent half the night in jail before they were let out. They had to go to trial, and they were fined.

“Louis was never beaten up, but some of our members picketing in New Orleans were beaten when they were arrested. New Orleans was rough. James Jackson went down to New Orleans to work with Raymond Tillman, who was organizing. Ray lived in New Orleans, and it became too dangerous, and both of them finally had to leave.”

In 1942 the Southern Negro Youth Congress invited Paul Robeson to sing at their meeting in Tuskegee, Alabama. What made the concert more notable than usual was that it was integrated.

DOROTHY BURNHAM “Paul was a person very outspoken about civil rights. He refused to sing before segregated audiences. I remember one year Marion Anderson came to Birmingham, and she couldn’t stay in a hotel. She stayed with a woman near us who had a rooming house, who entertained the black guests as they came through the city. Marion sang to an audience that was segregated, but Paul would not. He rarely performed in the South because of that. In Tuskegee, when he came and sang, the audience was integrated. When Glen Taylor, who ran for office with Henry Wallace, came to Birmingham to speak, we decided the audience would be integrated, and they arrested the minister of the church and my husband.”

Though their civil rights work may not have had much short-term effect in the South, what is clear, looking at history, is that their actions had an important effect on President Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal.

DOROTHY BURNHAM “Esther Jackson was James’s wife, and I do know that she and some of the young members of SNYC once met with Eleanor Roosevelt. Eleanor was interested in the youth and the youth congress, and they met and discussed some of the items on the agenda of the youth organization. She saw there were organizations out there really struggling, and Franklin Roosevelt’s actions in the areas of housing and health care were certainly in response to the pressure he was getting from these organizations. The unions, which were much stronger than they are today, also were able to apply pressure, and many of the unions supported the black movement.

“One of the campaigns I participated in in New York was to get baseball desegregated. I was involved in some of the marches to get black players into the league. We marched in New York. In Brooklyn I also campaigned on Fulton Street to get the Woolworth’s store, which was in the middle of Bed-Stuy, to hire black salespeople. They had all white salespeople, didn’t hire any blacks. Blacks were only working as cleaners in the department stores. A&S didn’t even have a black elevator operator. So we campaigned in front of Woolworth’s many, many months, and they finally gave in and started hiring black salespeople. At the same time, in Harlem, Adam Clayton Powell was leading the demonstrations on 125th Street against the Woolworth’s there.

“As for Jackie signing with the Dodgers, any struggle we won was big. We could realize that if you struggled for something hard enough, you might be able to win a change in the system.”

Paul Robeson and Ben Davis.

Library of Congress

Robinson’s entry into baseball was one of the last successes of the Progressive Movement before the right-wingers in the government used the repressive and unconstitutional Smith Act to destroy anyone they wished who was connected in any way with the Communist Party. Though not a single one of the 140 defendants was ever found to have committed a single act against his country, the wording of the Smith Act enabled prosecutors to dismantle and scatter groups dedicated to social justice and racial equality.

After firing hundreds of college and high school teachers in New York City under the Rapp-Coudert Commission hearings and under the Feingold Law, the House Un-American Committee, under the Smith Act, prosecuted anyone who was a member of the Communist Party. Many civil rights and union activists were stopped cold. Some were jailed. Some went into hiding. Others fled the country. Illegal or not, the right-wingers used the Smith Act to end any effectiveness these people might have had. And all their dangerous, hard work for social justice and civil rights in hostile cities across the country has been forgotten or, worse, ignored.

DOROTHY BURNHAM “Many of the teachers who were prosecuted were people who had been active in forming the teachers’ union, and in prosecuting them they tried to scare away other people and scare away business, and in that they were quite successful. I was friends with James Jackson, who had to hide, and with Claudia Jones, a very close friend who had to leave the country. It was really very hard to take. I attended some of those trials. It was difficult. McCarthyism was a really bad time. The best teachers I had at Brooklyn College were prosecuted and lost their jobs. The FBI followed us. They even followed my children to school. Our phone conversations were tapped. We had to be careful what we said on the phone, because we knew anything we said was being recorded. It was very difficult.

“Because of the continuing efforts of the FBI, the financial support for SNYC dwindled. Some of our advisors, who were college presidents and professors, were threatened, and they resigned, so it was difficult to keep the organization going. That’s when we moved back to New York. Louie came back and worked on the Henry Wallace [1948 presidential] campaign. Louie and Paul Robeson then started Freedom magazine, and they got people in the movement to contribute to it. Paul wrote a weekly column, and Alice Childress and Lorraine Hansbury were contributors. It lasted a few years, but it was difficult to keep going because you had to continually fund-raise, and there were no automobile ads to pay for it. What I remember most about Paul was that in spite of the fact he was so famous, he was a very friendly and open person. He was very open and anxious to get to talk to people and get to know them. He and his wife, Essie, were really dedicated to changing conditions of black people in the United States, that’s for sure.

“It surprises me that our civil rights work in the South has disappeared from the history books. I’m surprised at that, because many of the liberals bought into that, the idea that the Communist Party was completely negative, pushing for totalitarian government. I didn’t know a single person who advocated the overthrow of the American government. They were advocating changes in racism and discrimination policies, to get equality, but certainly not to overthrow the government. I’m proud to say we did play a role nationally and internationally, because we were able to send people to conferences to talk about the segregation and racism in the South, so people could understand.

“I can’t explain why no one talks about our work in the South, but my feeling is for the children of this generation and the coming generation, it’s going to be very, very difficult in terms of our getting all the things people need—housing, health care, and so forth. The poor and the working class are getting out of reach, and the organizations have been splintered. The trade unions have to be rebuilt, and you have the threat from globalization, which didn’t exist before. The problems of people interested in change are very great.

“It’s a different world, but it’s not working in favor of the working class—yet.”