AS WE LIVE THROUGH THE FIRST DECADE OF THE TWENTY-FIRST century, it is hard to remember what life was like for blacks in the mid-1940s. Jack Foner, Henry Foner’s older brother, wrote a book called Blacks and the Military in American History. In it Foner recounted the treatment of the more than a million black men and women who were inducted into the American armed forces, half of them overseas. The most shocking fact was that because of the racist policies in place at the time, 90 percent of those soldiers were not permitted to serve in combat units, but were used as laborers, building roads and bridges.

Wrote Foner, “The war provided a fascinating social laboratory in which to observe a nation’s schizophrenic behavior when its professed ideals conflicted with its treatment of one-tenth of its citizenry.”

Before Pearl Harbor, blacks who volunteered to serve were turned down, and those who wanted to work in defense plants were denied jobs. To limit the number of eligible blacks, the army had a literacy standard, fourth-grade reading and writing.

In July of 1940, 4,700 blacks volunteered to serve. Two hundred were accepted as mess attendants to be servants for white officers. In November, eighteen blacks on the USS Philadelphia complained to the Pittsburgh Courier that their work was limited to waiting on tables and making the beds of the white officers. Nine of the men had been placed in solitary confinement. The letter writers warned other blacks not to make the same mistake of becoming “seagoing bellhops, chambermaids, dishwashers, in other words mess attendants, the one and only rating any Negro can enlist under.”

Three of the signees were thrown in prison. The others were discharged.

An editorial in the newspaper P.M. stated, “Negroes cannot help but feel that their country does not want them to defend it.”

When the draft bill was passed on September 14, 1940, nothing was said about protecting blacks from discrimination. A. Philip Randolph, the founder and president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and other black leaders met with government officials two weeks later to present a program to end discrimination. Secretary of War Henry Stimson voiced his opposition to the proposals. The army had millions of Southern white Christian inductees, and he didn’t want to do anything to offend them. The Red Cross even refused to take blood from blacks, knowing how many whites would refuse it if they knew.

Black soldiers with Eleanor Roosevelt. Library of Congress

On October 9, 1940, Franklin Roosevelt announced changes. The armed services would draft blacks in proportion to the population. There would be three National Guard units of blacks, but the officers would be white. Blacks could fly and be eligible for Officers Candidate School. But the policy of segregation would remain, and the policy that prevented blacks from becoming officers also stood.

In January of 1941 a frustrated A. Philip Randolph announced that on July 1 there would be a march on Washington protesting how blacks were treated in the armed forces. To forestall the march, President Roosevelt issued an executive order banning discrimination in defense industries. The result was the placement of blacks in war industry jobs, but nothing changed in the military. Not even after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, a black college student declared, “The Army Jim Crows us. The Navy lets us serve only as messmen. The Red Cross refuses our blood. Employers and labor unions shut us out. Lynchings continue. We are disenfranchised, Jim Crowed, spat upon. What more could Hitler do than that?”

What led to an increase in the number of blacks accepted into the armed services were the increased manpower needs. In March 1942, the Army Air Forces began taking applications from black youths. A month later, under pressure from President Roosevelt, a limited number of blacks were accepted for general service. In the meantime, whites and their families were complaining that the military was taking them while they were turning down single black men. Beginning in June of 1943, inductees previously rejected for failing the literacy test were sent to Special Training Units in the army to learn to read and write. When they passed, they were sent to basic training. By 1945 over a million blacks had been inducted.

But once inducted, most black soldiers didn’t fight. They were concentrated in the service sector, building roads, stevedoring, doing laundry, and fumigating. Even blacks who passed basic training with flying colors were shipped out to perform common labor.

Said one black at an air base, “It is not like being in a soldier camp. It is more like being in prison.” Wrote a compassionate white soldier, “The Negroes are segregated from the minute they come into the camp…the whole picture is a very sad and ugly one. It looks, smells, and tastes like Fascism.”

Suggestions were made over and over to integrate volunteer divisions. The War Department always said no, refusing to tamper with the established American way of life.

Southern whites more often than not were assigned to command the black troops. Wrote one black enlisted man about his superior officer, “His obvious dislike for Negroes seemed to be a prime qualification for his assignment with Negro troops.” When black soldiers complained to the press, the army banned black newspapers in post libraries and from sale at the PXs.

Blacks who knew their rights and insisted on exercising them were threatened with court-martial. They were considered “bad Negroes,” and they would be assigned the most unpleasant and humiliating tasks to break their spirit.

In the summer of 1943, the 92nd Cavalry Division, comprised of black troops, was broken up, and the men were assigned jobs unloading ships, repairing roads, and driving trucks. They were forbidden from writing home about it. Secretary of War Stimson defended the move, saying it was done in the name of efficiency. Said Stimson, “In that so many blacks were poorly educated, many of the Negro units accordingly have been unable to master efficiently the techniques of modern weapons.” As though the white soldiers the army had taken were Rhodes scholars.

The black press called for Stimson’s resignation. The Republicans immediately applied their spin, appealing to blacks to vote for them, saying this was a Roosevelt administration policy. The Democrats blamed the military.

The upshot was that the men were restored to combat duty. The 92nd arrived in Italy in 1944, and they won seven thousand medals. When morale of the division was investigated by Newsweek, the journalists discovered that it was extremely low among the troops. The black soldiers were convinced it was more important to the white cracker officers to make their life miserable than it was to win the war.

After the Battle of the Bulge, which led to great loss of life among American soldiers, the military had no choice but to retrain blacks in supply and service units to turn them into riflemen. The plan was for these men to fight on the line alongside whites on a fully integrated basis, but General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, said no. Blacks were instead organized into platoons to fight alongside white soldiers. But the policy of keeping whites and blacks separate was broken. Twenty-five hundred blacks fought along white soldiers across Germany to the end of the war.

Said Brigadier General Charles T. Lanham to the black volunteers, “I have never seen any soldiers who have performed better in combat than you.”

Afterward the army took a poll of the white soldiers who had fought alongside them. Three out of four said their respect for the black soldiers had grown. The survey was classified and never made public. At the end of the war the blacks were returned to all-black units and discharged.

In the Army Air Forces, six hundred blacks, the Tuskegee Airmen, flew over Africa, France, Poland, Romania, and Germany. Operating as fighter escorts in two hundred missions, not one bomber was lost to enemy fighters. The black fliers were credited with shooting down 111 enemy planes in the air and 150 others on the ground.

Not a single black soldier received a Congressional Medal of Honor.

If treatment was rough for black soldiers, it was far worse for the few black officers, who were regularly abused and humiliated in the presence of their men by white unit commanders. Black officers were required to sit in the back row of an army theater while front seats were reserved for white officers and Italian prisoners. In Italy an officers’ club was set up by black soldiers. When it was completed, black officers were barred from eating there.

In March 1945, black officers of the 477th Bomber Group, an all-black outfit at Freeman Field, Indiana, were refused service and threatened with arrest if they insisted on entering the clubhouse. The officers were required to sign an agreement that they would accept the segregation of the base. One hundred and one officers refused. It was an officers’ club, and they insisted on using it. They all were arrested and held in prison for a month, when the War Department dismissed the charges. Numerous black officers had breakdowns. Many sought transfers and discharges.

When black soldiers in uniform returned to their hometowns, danger awaited. A black sergeant was killed in March 1943 by a city policeman on the streets of Little Rock, Arkansas.

Wrote a black sergeant from the China-Burma-India theater of operations, “I have a very clear idea of what we are not fighting for. We certainly are not fighting for the Four Freedoms.”

Attorney General Francis Biddle warned Roosevelt in November of 1943, “The situation among the Negro voters is still serious. The greatest resentment comes from Negroes in the armed forces, particularly those who have been in southern camps, and they are writing home about it.”

Shortly before the war ended, the War Department called upon Congress to pass a bill making it a federal offense to attack or assault men in uniform. The bill never passed.

In the summer of 1944 a directive was posted to ban segregation in theaters, post exchanges, and buses operating within army camps. The directive was ignored.

Change came only after the death of Secretary of the Navy William F. Knox on April 28, 1945. He was succeeded by James A. Forrestal of New York. The navy abandoned segregation of advanced training schools. Recruit training, though, remained segregated. Blacks were assigned to ships with whites, but they could only make up 10 percent of the crew.

In July 1945, at the Great Lakes Naval Station, two black companies were placed in the same battalion as four white companies. A black company won battalion honors.

In August 1945, Captain Richard Petty, who was in charge, moved to integrate the companies. They shared the same barracks and mess. Not long afterward, the mixed company named a black sailor as its “honor man.”

Said Captain Charles Alonzo Bond, commandant of the service schools, “Segregation was an egregious error. It was un-American and inefficient—a waste of money and manpower.”

Monte Irvin in the uniform of the armed services. Courtesy of Monte Irvin

But for most black soldiers, their experiences during World War II would color their way of looking at whites and at American society forever. Wrote James Baldwin, “The treatment accorded the Negro during the Second World War marks for me a turning point in the Negro’s relation to America: to put it briefly, and somewhat too simply, a certain hope died, a certain respect for white Americans faded.”

Jackie Robinson is justifiably celebrated as the first African-American to break the “color barrier” in major league baseball. But Robinson was Brooklyn Dodger general manager Branch Rickey’s second choice for the job. His first pick was a mild-mannered outfielder for the Newark Giants, by the name of Montford Merrill “Monte” Irvin. He was born in Haleberg, Alabama, in 1919. Irvin’s father was a sharecropper who migrated north in 1927 and settled in Orange, New Jersey, where son Monte became a four-sports star at Orange High School.

He attended Lincoln College for a year and a half, and in 1938, while still in college, played for the Newark Eagles of the Negro Leagues under the assumed name of Jimmy Nelson. When his father called him home to help the family out financially, he quit college in 1939 and joined the Eagles for good at age twenty.

When Jorge Pasqual, the owner of the Mexican League, offered him a significant raise over what the Eagles were paying him, $500 a month, he spent the 1942 season playing in Mexico. It was the best year of his life. For one season he was able to escape the brutal racism of America.

Then came the war, and he was drafted into the army, and those were the worst years of his life. Being black, he was humiliated and harassed by the white Southern officers.

Irvin was discharged from the army in September of 1945, and in October Clyde Sukeforth, Branch Rickey’s scout for the Great Experiment, asked Monte Irvin to sign with the Brooklyn Dodgers, to be the first black player in baseball. Irvin, a bright, gentle man with extraordinary skill, who might well have become as lionized as Muhammad Ali, said no. The years in the military suffering under the abuse of cracker officers and a policy of neglect and abuse by the army had left him in no condition, either physically or mentally, to take on such a challenge. It was bad enough he had been away from the game for three years. But the three years of relentless torture he had endured from having to put up with racism in the army made it impossible for him to face yet another, more difficult struggle of black liberation. Feeling but a shell of himself, Irvin told Sukeforth that after he got back into shape and into the right frame of mind to play, he would call the Dodgers.

Irvin didn’t call until 1949. By then Jackie Robinson had been in the National League two years, and with Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Larry Doby, and Satchel Paige joining major league teams, the presence of blacks was becoming more accepted. Irvin signed with the New York Giants and helped lead them to pennants in 1951 and 1954, and in 1973 he was elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame. Today he lives in retirement in Houston, Texas. He is content. He gives Jackie Robinson all the credit in the world, and he has never looked back.

MONTE IRVIN “I joined the Newark Eagles in Daytona Beach, Florida, in 1939. I was twenty years old. I learned how to play all positions. I was noted for my arm. I had an arm better than anybody. I hit to all fields, hit the long ball, and I could run.

“The Eagles played about 140 games a year. In 1942 I was making $150 a month. The head of Mexican baseball, Jorge Pasqual, sent me a telegram saying he’d give me a salary of $500 a month, and $250 a month for an apartment, if I agreed to come to Mexico.

“I showed the telegram to our owners, Abe and his wife Effa Manley, and they said, ‘We can’t match it.’ I said, ‘I’m only making $150. Just raise it to $200, and I’ll stay.’ He said, ‘No, Monte, I have all these other stars to pay.’ I said, ‘Then I’m going to Mexico.’

“That was the best year of my life. I played right in Mexico City. I was the league’s MVP, was among the home run leaders, hit .397, and had a wonderful time playing there. In Mexico, for the first time in my life, I felt really free. You could go anywhere, do anything, eat in any restaurant, go to any theater, just like anybody else, and it was wonderful.

“In 1942 the Negro League owners and the players took a poll, asking which player would be the perfect representative to play in the major leagues. They said I was the one to do it, the perfect representative. I was easy to get along with, and I had some talent.

“Then I went into the war, where I was treated very shabbily. I was with a black unit of engineers in England, France, and Belgium. More than anything else, we weren’t treated well in the army. They wouldn’t let us do this. We couldn’t do that. The guys said, ‘If they weren’t going to give us a chance to perform, to reach our potential, why did they induct us into the army?’

“We had a lot of problems with our own soldiers and sailors. Other guys said, ‘Maybe we’re fighting the wrong enemy.’

“We trained at Camp Clayborne, in Louisiana. It wasn’t a good situation. There was a black tank outfit at Camp Clayborne, and by the time they came off the field and took a shower, the PX had sold out of everything—no beer, no ice cream, no soda, no soft drinks. The men just got fed up. They got in their tanks and tore all the PXs down with their tanks. They had to send over to Mississippi to get an antitank outfit to stop them. Two weeks later they were shipped over to Africa to fight. They said, ‘Damn, they should have done this many months ago.’

“All of our commanding officers were white. In England we had a Southerner who had no business being a company commander, and he made some remarks about no fraternization with whites, said we couldn’t do this, couldn’t do that. After he spoke, we had a company chaplain who got up and said, ‘Men, you’re members of the United States armed forces. You can do anything anybody else can do. I assure you, this company commander will be gone in two weeks.’ And he was. He was replaced by a lieutenant, a black company commander. This was 1944 in England, in a little town called Red Roof in southern England.

“We didn’t think we were ever going to get back home. We felt like we were thrown away. We built a few roads, and when the German prisoners started to come in, we guarded the prisoners. We said, ‘It would have been better if they hadn’t inducted us and just let us work in a defense plant.’ They wouldn’t let us do anything. We were just in the way. They were going to send us to the Pacific, but then after the bomb dropped, they sent everybody home.

“I got home on September 1, 1945, and in October I started playing right field for the Newark Eagles. I had been a .400 hitter before the war, and I became a .300 hitter after the war. I had lost three prime years. I hadn’t played at all. The war had changed me mentally and physically.

“We played an all-star team in Brooklyn. Ralph Branca and Virgil Trucks struck out about eighteen of us. Trucks and I visit every year, and we talk about the old days. I won’t say, the Good Old Days. The Old Days.

“Clyde Sukeforth, the scout for the Dodgers, had Campanella and me come over to the Brooklyn office in October of 1945. I signed with the Dodgers, but I told them I had had a tough time during the war. I said, ‘I don’t have the skills I used to, and I don’t have the feel for the game I used to.’ I told them I needed a little time to get my act together. They said, ‘Okay, let us know when you’re ready, and we’ll bring you up.’

“In order to get back on track, Larry Doby and I went to Puerto Rico to play in the winter league. They gave us $500 a month. I was paid as high as $1,000 a month in the Negro Leagues.

“I didn’t feel I was ready until I played in the Cuban Winter League in 1949. I called the Dodgers and told them I was ready. Meantime, the Eagles owner, Effa Manley, said, ‘Mr. Rickey, you took Don Newcombe from our team. I’m not going to let you take Monte. You’re going to have to give me at least $5,000.’ So rather than get in a lawsuit, the Dodgers released me, and the Giants gave the Eagles $5,000 and picked up my contract. I didn’t get a nickel of it. I asked for half, but Mrs. Manley said, ‘No, I worked so hard to get this done. I’m going to split it between my lawyer and myself.’ She took the $2,500 and bought a fur stole with it, and when I saw her twenty-five years later, she was still wearing that same fur stole.

“On July 8, 1949, Hank Thompson and I reported to the New York Giants. Leo Durocher came over and introduced himself. And when everyone got dressed, he had a five-minute meeting. He said, ‘I think these two fellows can help us make some money, win a pennant, win the World Series. I’m going to say one thing. I don’t care what color you are. If you can play baseball, you can play on this club. That’s all I’m going to say about color.’

“This was two years after Jackie. They had gotten used to seeing an African-American on the field. It wasn’t a picnic. We heard the names. But we didn’t have it as rough as he did.”

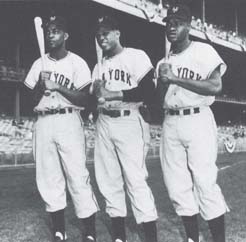

The first all-black outfield-—Monte, Willie Mays, and Hank Thompson. Courtesy of Monte Irvin