SAY WHAT YOU WILL ABOUT BRANCH RICKEY’S MOTIVES FOR bringing Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers, the fact remains that not only did Robinson become a great player who led the Dodgers to National League pennants in 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1956, but the UCLA-educated Robinson was exactly the sort of role model that Rickey envisioned him to be. Kids, both white and black, wanted to be Jackie Robinson. Playing on the streets, the kids tried to run the bases like him, emulated his batting stance, holding their bat high like he did, and through the phenomenon of hero worship, they intuited that Jim Crow not only was evil, but that racism’s premise that whites are better than blacks was a lie. It is safe to say that the American civil rights movement went into high gear with the coming of Jackie Robinson to Brooklyn.

IRA GLASSER “When I was a young boy growing up in Brooklyn, I was aware that no blacks were allowed to play major league baseball. Everybody I talked to who grew up in Brooklyn was aware of it. I was aware because my mother spoke of it, because it was a very big issue. She would say, ‘It’s outrageous.’ My father was a little grumpier about it. My mother thought Jackie Robinson coming to the Dodgers was social justice. I can remember her saying, as Branch Rickey intended her to say, ‘He’s a college-educated man, and he speaks so well.’ She bought into it. ‘Why shouldn’t a black man have a chance,’ she said. ‘This is America. What did we fight the war for?’

“My mother presented this to me in ways that made the racial situation in America a different version of anti-Semitism. What had happened to the Jews in Germany and what the blacks were suffering through in America were different examples of the same phenomenon.

“Years later, when people were talking about Norman Podhoretz and Commentary magazine, and how it had turned to the right, I said, ‘There are two kinds of Jews politically and racially. If you grew up in Brooklyn the way I did, you were taught to believe that racial injustice was the same thing as anti-Semitism in Germany, that what led to the concentration camps was the same thing that led to slavery and Jim Crow justice, that they were all aspects of the same thing, and therefore, if you were a Jew, racial justice was your issue. That they were part of the same phenomenon, judging people on the basis of criteria that were out of their control and irrelevant to their character and abilities. Later that came to be embraced with the disabled and women and gays. But that was not explicit then.

“The other kind was what I came to call the Norman Podhoretz Jew, Jews who grew up and were taught and came to believe that of all the forms of discrimination, anti-Semitism was the first among equals, that it was something special and extraordinary, that there was nothing worse than the Holocaust, including slavery. And for those Jews, they grew up protecting themselves against the demands of blacks. So the race issues became competition instead. These were Jews who weren’t for affirmative action, for example. These were Jews who opposed the blacks who wanted community control of their schools in Ocean Hill–Brownsville in the 1960s.

“During my early years at the ACLU, there were a bunch of Jewish lawyers around my age, who all shared the same sense of race and anti-Semitism as I did. And, with one exception, they were all Dodger fans. And they would tell you the same story. My love for Jackie Robinson wasn’t just my private obsession, it turned out. We all discovered we all thought the same thing. And that’s why I began to see it as a sociological and political phenomenon that was more serious than I first thought.

“The way I think it happened was this: my mother reacted to Robinson becoming the first black baseball player in the major leagues even though she wasn’t a baseball fan. So where did I learn about Robinson and what he had to go through after he joined the Dodgers? I was nine when Robinson came up, and most of us didn’t read the papers much. We were kids. And in those days sports columns weren’t sociological the way many of them are now, so you couldn’t learn about it from that. There was no television. There was just radio, which we were glued to. We lived on the radio. And no question, Red Barber, the Dodger announcer, reported what was happening to Robinson. Not only did he teach us baseball, explaining the strategy of the bunt and the sacrifice fly and the stolen bases that announcers today often don’t describe, but we knew what Robinson was going through because of Barber. We all remember—I’ve had this conversation with fifty different people. We knew the story about Rickey saying to Robinson, ‘You have to turn the other cheek.’ We knew that Robinson’s fiery temper was under wraps the first two years. We knew about Ben Chapman and the Phillies and the way they threw a black cat onto the field and shouted racial epithets at him.

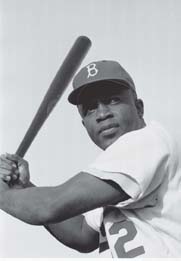

Jackie Robinson. Library of Congress

“Barber was from Mississippi, and he had a crisis of conscience as to whether he could stay the Dodger announcer. He wrote about how he gave up his racist attitudes to keep his job. I remember, when I was nine, learning from his broadcasts about Jim Crow segregation and public accommodations in hotels and restaurants. I learned that when Jackie and Campanella and Newcombe went on their road trips to St. Louis, they couldn’t stay in the same hotels as the white players, couldn’t eat at the same restaurants. That was the first time I learned about segregated public accommodations, and that was how I came to hate it.

“We were very connected, not just to the baseball part of it, but we all knew about Lena Horne, and we all listened to the Joe Louis fights and knew about the Louis–Max Schmeling fight. But there was no event that in 1947 was capable of communicating in a way that did not require a lot of book learning, a lot of explanation, no laws, no Supreme Court arguments, no Congressional debates, in an emotional way what was wrong with America and what had to be set right. And we ingested it. I say ingested, because it wasn’t cognitive. It was visceral, and everybody I ever talked to who was within three or four years of my age who grew up in Brooklyn in those years, knew all the stories. And we didn’t learn it because it was taught to us in the history books. It wasn’t talked about in school. There were no television discussions. It wasn’t because of Martin Luther King Jr. Most of it we learned in a general way from Red Barber, and it was important, because the Dodgers were our guys, and they were fucking with them. We would have hated it if they had done it to Duke Snider. I often joke that had I been a Yankees fan, I undoubtedly would have been a racist and would have had no sympathy for Robinson. I had a number of Yankee fan friends who deeply opposed racial subjugation, but what was a fact was that the Yankees were one of the last teams in the majors to have a black player, and that didn’t come until nearly a decade after Robinson came into the league. So what young Dodger fans went through with Robinson was different. What was important to us was not the color of his skin. What was important to us was the color of his uniform.

“Cause and effect are funny things. Part of who you end up rooting for as a kid is accidental. But whatever caused me to be a Dodger fan, it reinforced all those feelings about Robinson and race, and without quite expecting it, all of us were suddenly thrown into the middle of this incredible experiment in civil rights, which was unprecedented. This was just one year after World War II ended. This was before Truman’s order to desegregate the armed forces. This was eight years before Rosa Parks sat down on that bus. This was seven years before Brown v. Board of Education. As a nine-year-old boy who loved Jackie Robinson, I was confronted with this.

“On this team of heroes, there were many. But on that team all of us wanted to be like Jackie Robinson. I played a lot of serious fast-pitch softball into my forties, and my stance was always Robinson’s. I copied it when I was twelve years old, holding the bat high, taking your right hand off the bat as the pitcher wound up, and brushing your right hand on your hip, the little nervous tic he had. We modeled the way we ran the bases from him.

“Once in the 1970s one of my kids asked me, ‘Who today is like Robinson?’ I said, ‘To imagine Robinson dancing off third base, imagine the great Knicks basketball player Earl Monroe. No one had ever seen anything like that before, his fall-away slides, his hook slides, the way he would charge off third base, go way down the line, and come back. And he’d steal home. Kids today never saw anyone do that, because no one does it.

“The other thing that was significant about those years and that was visceral and entered our souls in a most effective way was Ebbets Field. In 1947 Ebbets Field was the only integrated public accommodation in America. It was an astonishing experience for a nine-year-old boy. I would go with a couple of friends, or by myself. My friend Donald Shack is ten years older than I am, and he remembers Ebbets Field as entirely white. I remember it as integrated. I remember going to Ebbets Field as a ten-year-old and sitting in the grandstands next to this guy who I thought of as old, but who might have been in his thirties, this burly black guy in an undershirt and a bowler hat, with a big cigar and a beer, and the two of us were sitting next to each other, and we were Dodger fans. If Furillo threw somebody out at third base, we were up punching each other in the arm, and if Robinson took second on a pop-up to short left field, we were hugging. There was no color there. But there was color everywhere. Where else in 1948 could a ten-year-old boy be sitting next to a black man in a comfortable, familiar way and in common cause? Embracing physically? Touching? And feeling natural and safe. And not being aware of it. Only years later did I realize, Oh my God, what an incredible psychological experience in the kind of society we lived in in 1948! And you learned early from watching Robinson and Campanella and Newcombe that what my mother said when I was five was true: that skin color was as meaningless as eye or hair color, that it said nothing about whether a man could steal second base or hit a baseball, and from there it was not hard for a kid to think ten years later that it also meant nothing as to whether a black man could teach mathematics or run for office, that it was not a quality that had any relationship to talent or character, and because Robinson was not just a talent, but a man of incredible character, the linkages that got established in an unconscious and visceral way for kids nine, ten, and eleven went way beyond the simple notions of ‘A black man should have a chance.’ The whole experience destroyed the mythologies that perpetuated racism.

“So the Robinson experiment was enormously underestimated—not only underestimated but unrecognized for decades as a value-driven impact on white kids at a time when America was segregated, even in a city like New York. As I said, where I lived, I could walk as far as I could walk in any direction and not find anyone who wasn’t white or Jewish, but suddenly I’m sitting in Ebbets Field, and I’m identifying with the struggles of a black man for equal opportunity. I want to play like number 42. If I’m playing in an empty lot in Brooklyn, I’m copying him. And what that meant for a nine-and ten-year-old kid, modeling yourself and identifying with him, that was unrecognized and underestimated as a force. And it tells you something about the way value education actually takes place. It had far more of an impact than the traditional highlights of the civil rights movement, starting with Brown v. Board of Education, Rosa Parks, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.”

Ira Glasser, upper right, and friends in Cooperstown.

Courtesy of Ira Glasser