Library of Congress

THE LAW THAT GAVE RISE TO THE PERSECUTIONS OF THE LEFT in the 1940s and the 1950s was written by an antilabor, segregationist congressman by the name of Howard W. Smith, a Democrat from Virginia. Formally titled the Alien Registration Act, but more widely called the Smith Act, it made it a federal offense for anyone to “knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association.”

It was the first statute since the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1789 to make a crime out of advocating an idea.

The bill was signed into law by Franklin Roosevelt in 1940.

The first prosecution under the act was against Communist leaders in Minnesota who were advocating that the Teamsters strike for better wages. The Communist Party at the time was also campaigning to stay out of the war.

The evidence the prosecution used were readings from the Communist Manifesto as well as writings by Lenin and Trotsky. They also called two witnesses who said that a couple of the defendants had told anti-war soldiers to complain about the food and the living conditions.

On December 8, 1941, one day after fear gripped the country in the wake of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the jury handed down its sentences. Twelve defendants got sixteen-month terms, and eleven others received a year in jail.

In 1944, there was another trial, this time in Washington, DC, of men accused of supporting the Nazis. Charles Lindbergh was not a defendant, and neither was Joe Kennedy, even though they were well-known Nazi sympathizers. But under the Smith Act, they could have been. After the prosecutors failed to come up with any evidence, a mistrial was declared and everyone went free. Freedom of speech won out this time around, but certainly not the next.

Howard W. Smith. Library of Congress

The framework for the House Un-American Activities Committee, with its platform for hunting out Communists in the 1950s had its beginnings in 1938 with the establishment of the Dies Committee. The sole function of this body was to “expose” threats to America’s way of life. It was supported by liberals like Congressman Samuel Dickenson, who had become alarmed at the growth of the German Bund and of anti-Semitism. Its focus, however, always was anticommunism.

Representative Martin Dies Jr. of Texas originally supported the New Deal, but by the late 1930s he had become a vocal opponent of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal programs, as he had become obsessed with what he saw as the subversive threat from the left. He introduced to the House a resolution calling for a special committee to investigate “un-American propaganda” instigated by foreign countries. His intention was to investigate Communists, Socialists, Trotskyites, and those who were not members of those organizations but who held similar beliefs. On May 26, 1938, the House voted to establish the committee, and Dies became its chairman. His chief investigator was J. B. Matthews, publisher of Father Coughlin’s anti-Semitism-laced book, Social Justice.

Dies wanted to go after those who were advocating change. But Dies had one unmovable roadblock in his way—Franklin Roosevelt, whose social reforms included welfare, taxation, and the WPA, and who drove the conservatives and especially the Christian right to hate everything he stood for. William Randolph Hearst, a fierce Roosevelt critic, called the president “Stalin Delano Roosevelt” for his “bastard taxation” program, which was “essentially Communism.” As long as Roosevelt was alive, Dies and his committee would constantly be frustrated and blunted. But even Roosevelt couldn’t stop them from wreaking some havoc.

The American Federation of Labor was battling the Congress of Industrial Organizations for control of labor unions. Dies’s first witness was John Frey, the president of the Metal Trades Department of the AFL. Frey testified—without providing any evidence—that the CIO was filled with Communists. He identified as Communists 283 CIO organizers. Dies accepted his testimony, and headlines and firings followed.

Martin Dies. Library of Congress

The next witness, Walter Steele, a self-appointed “patriot,” testified that there were Communists in the Boy Scouts and in the Camp Fire Girls. Reporters rushed to print the allegations, as ridiculous as they may have been. Again, those who were named were not accused of having done anything. It was accepted that just belonging to the Communist Party was enough to find one in the wrong.

The political nature of why Dies was doing what he was doing was highlighted when he went after the Federal Theater Project of the Works Project Association, which employed several thousand writers and actors. Dies hated that Roosevelt and his government were spending money on keeping artists and writers from starving. Dies, moreover, didn’t like the kind of plays being staged. As far as Dies and his committee were concerned, any play with a social issue at its core was a “Communist play.”

When the director Hallie Flanager was asked about an article she had written about the English playwright Christopher Marlowe, Congressman Joe Starnes ignorantly asked her, “Is he a communist?” All across America there were howls of protest and derision. Nevertheless, the investigation was enough to kill the theater project.

Dies’s House Un-American Activities Committee was scheduled to expire in 1938, but Dies petitioned to keep it going. The public was very supportive. All the while Dies accused President Roosevelt of refusing to pursue subversives.

In 1939 Dies went after an organization called the American League for Peace and Democracy. It had twenty thousand members, and it presented Dies with yet another opportunity to try to embarrass President Roosevelt.

When the offices of the ALPD were raided, on the list of members were Harold Ickes, the secretary of the interior, and Solicitor General Robert Jackson. The release of 560 names on the list created a firestorm. President Roosevelt condemned HUAC’s action as a “sordid procedure.”

Dies pushed to prosecute the organization, but Attorney General Francis Biddle said it hadn’t broken any laws. Nevertheless, the notoriety caused the organization to dissolve.

In 1940 Dies began to investigate the Communist Party itself. It raided the party’s office in Philadelphia and carried off documents. A U.S. district court judge, upset by the lawlessness and unconstitutionality of HUAC’s action, ordered the investigators arrested. Dies accused the judge of protecting “agents of foreign dictators.” Even though Dies pressed the campaign, the Communist Party officials, citing their rights under the constitution, refused to testify.

Under the law, Dies was obligated to go before the full House to ask for contempt citations. He ignored the law, and he got warrants without having the authority to do so. Dies brought the hearings to a close without further action.

Then in 1940 Congress passed the Smith Act. The bill passed the House by 382 to 4. The one country that heaped praise on Dies and HUAC was Nazi Germany. When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the Russians became our wartime allies, but Dies nevertheless viewed the Communists as a greater danger to our national security than the Nazis.

Pursuing his political agenda, Dies went after Vice President Henry Wallace. Then in 1941 he ordered the Justice Department to investigate more than a thousand federal employees accused of “subversive” activities. After all 1,121 were investigated, Attorney General Francis Biddle fired exactly 2. Dies, furious, accused Biddle of dereliction of duty.

Dies released yet another long list of federal employees to be investigated. One employee, William Pickets, who was black, was singled out, and the House moved to cut his salary. An uproar ensued. The resolution to cut his salary was killed.

When Roosevelt ran for a fourth term in 1944, Dies went after him again. He attacked Sidney Hillman, the chairman of the CIO Political Action Committee, a close advisor to FDR. The CIO PAC had been campaigning to defeat all the members sitting on HUAC. Dies said that this proved they were pro-Communist.

In 1945 Dies, in poor health, announced he would not seek reelection. But HUAC did not expire with his departure.

The man who saved HUAC was John Rankin, a racist from Mississippi. Using his knowledge of procedure, Rankin offered an amendment to make HUAC a permanent committee and also gave it broad investigative powers.

When FDR died on April 12, 1945, HUAC could start operating without its most powerful foe. In 1945 Rankin went after subversives in Hollywood. None of the victims was found guilty of anything. Those convicted were convicted either of contempt or perjury. Then, in November 1946, Republicans took control of both houses of Congress. One of the new members of HUAC was Richard Nixon of California.

One of the first actions of President Harry Truman was to ask Attorney General Tom Clark to make a list of subversive organizations. The list included any group for workers’ rights and especially for civil rights. Said Jack O’Dell, a civil rights activist, “Every organization in Negro life which was attacking segregation per se was put on the subversive list.”

In 1947 Truman warned the nation of the Cold War with the USSR. In a speech he said it was up to the United States to support “free peoples of the world in maintaining their freedom.” His approach to international relations would be called the Truman Doctrine. The Communist threat now would be seen in global, apocalyptic terms. The Soviet Union was now our enemy, and anyone who in the past had supported the communist ideology was now suspected of being disloyal or subversive by definition.

On March 21, 1947, nine days after his Truman Doctrine speech, Truman signed an executive order creating a loyalty program for federal employees.

It was up to the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover to enforce the Truman Loyalty Program, which meant that Hoover now had carte blanche to repeat, if not improve, his performance during the Palmer Raids of 1919. The antiblack, antiunion Hoover was to become both the chief investigator and the mastermind of the Great Inquisition known as the McCarthy period. The “high priest of American anticommunism,” Hoover was seen as a Christian soldier fighting for peace in America.

Hoover had taught Sunday school as a high school student. He became a lawyer through going to night school while working as a messenger at the Library of Congress. He was a file clerk at heart, but he had the power to conduct an inquisition. His FBI staff had limitless power. His domain was secret, and secrets. He used hearsay, rumor, snitching, backbiting, and innuendo. He was not above using blackmail, even against the nine presidents he served.

The great irony was that the one country that condoned such secrecy as practiced by its police was the Soviet Union, followed later by East Germany. When Attorney General Charles Bonaparte proposed a Bureau of Investigations in 1908, Congress turned down his request because it felt such a unit would create a “blow to freedom and to free institutions.” A month after Congress adjourned, Bonaparte established the future FBI anyway. He was supported by President Theodore Roosevelt, who accused Congress of being soft on crime. The United States now had a secret police that rivaled the one of czarist Russia.

Said historian Richard Gid Powers, “All the institutions young Hoover joined—Sunday school, church, Central High—regarded themselves as defenses against the immigrant threat to the nation, hegemony, its character as all-but-officially Christian nation, and to the national leadership of the old-stock American.”

This was as true in 1949 as it was in 1919. America after World War II was changing. Urbanization, increased social mobility, the rise of consumerism, a shift toward the emancipation of women and blacks and most of all the decomposition of traditional religious patterns—all of this scared the shit out of conservatives. For Hoover, the immigrant and the radical were part of what he saw as a larger pattern of lawlessness belonging to a modern world.

Hoover felt the ground under his feet moving, and he became scared. In the 1920s he had gone after Emma Goldman and her ilk, and it hurt his reputation in the eyes of the public. He then turned to gangsters like John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, and Baby Face Nelson, and with a savvy media campaign he became known as America’s G-Man.

By the mid-1930s Hoover was famous, and after the death of Franklin Roosevelt, he would be unleashed by Harry Truman to go on the warpath against communists. Along the way he not only wiped out the Communist Party in America, he went after a generation of men and women devoted to social justice, the labor movement, and civil rights.

Hoover was a Red hunter in the same way the Puritans were witch hunters. Both were fueled by superpatriotism and fear. Hoover, a stone-cold racist, justified what he was doing by saying that if the FBI didn’t do it, America’s citizens would.

Hoover, who was both obsessive-compulsive and gay, began attacking the sexuality of Americans in the 1920s. He went after those who violated the Mann Act—people who crossed state lines to have sex. He said it was essential for the law to attack “the problem of vice in modern civilization,” and he said he was not going to rest until America’s cities were “completely cleaned up.”

He talked about communists in sexual terms, calling them “lecherous enemies of American society.” He often referred to the left wing as “intellectual debauchery,” and warned his agents of the “depraved nature and moral looseness” of student radicals.

After civil-rights worker Viola Liuzzo was murdered, Hoover sent President Johnson a memo saying: “A Negro man was with Mrs. Liuzzo and reportedly sitting close to her.” Due to the presence of a Negro with her, Hoover refused to investigate, feeling she deserved what she got.

Martin Luther King Jr. was his special target. Hoover called him a “tomcat with obsessive degenerate sexual urges.” After King was assassinated, Hoover planted an item with columnist Jack Anderson, saying that James Earl Ray had been contracted to kill King by a white husband whose wife had borne King’s child.

The average American did not really care very much about communists, but because Hoover was sexually tormented, he went after gays in the U.S. government, causing more homosexuals to be fired by the State Department than communists. He focused his efforts by displacing a whole range of dangers onto the one master signifier of communism. Thus he could blame on communism everything that wracked his twisted soul, using the power of his image as the “omniscient, incorruptible protector to convince others that the attack would bring security to all Americans.”

Hoover may have had a twisted soul, but he needed a front man to conduct the witch hunt that he so desperately desired. That man appeared quite by accident on February 9, 1950, in Wheeling, West Virginia, at a meeting before the Ohio Country Women’s Republican Club. During dinner the man, Joseph McCarthy, a senator from Wisconsin who had come into office in 1946, along with California senator Richard M. Nixon, was discussing with his cronies how he could revive his flagging political fortunes. When he got up to speak, he told the assemblage that “While I cannot take the time to name all of the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring, I have here in my hand a list of 205 names…” McCarthy went on to say that the secretary of state had their names but allowed them to work anyway. In a similar speech in Salt Lake City the next day, he must have noticed a bottle of Heinz ketchup on the table, because to that assemblage he said he had a list of “57 communists in the State Department.”

It was nonsense, of course. Hoover had told McCarthy that there were Russian spies in the State Department, but McCarthy didn’t know who they were and had no way of uncovering them. As A. Mitchell Palmer had done in the 1920s, McCarthy merely assumed that anyone who had ever belonged to the Communist Party was subversive. It may have been a fishing expedition, but it was exactly what J. Edgar Hoover and wealthy conservative Christians such as oil moguls Clint Murchison, Hugh Roy Cullen, and H. L. Hunt wanted to hear. It was Hunt who once said, “Communism began in this country when the government took over the distribution of the mail.” The oilmen were strident haters of all Franklin Roosevelt had stood for. Roosevelt, after all, put a cap on how much oil their companies could drill, and he and the Democrats were behind laws that forbade them from drilling sideways into neighboring oil fields, a shabby practice that had gone on for decades.

Once the media spread the word of what McCarthy was saying, it wasn’t long before he in the Senate and the equally determined House Un-American Activities Committee launched the most far-reaching witch hunt since the Salem trials.

The McCarthy and HUAC rampage was fueled by fear, and there was no greater fear than of the Soviet Union after it tested its first atomic bomb in 1949. Stalin, once our ally, now had nuclear weapons. That year Mao took over in China, turned it Communist, and in 1950 the Korean War broke out. There was panic in the land. A ferocious repressiveness became the order of the day. Only a secure suburban home, populated by a nuclear family, Dad presiding, could provide protection against the outside agitators. It was an era when a lot of people built bomb shelters to house their family in case the worst occurred. And here was a U.S. senator saying that members of the State Department were card-carrying Commies who were out to destroy our way of life.

When it came to the communists, McCarthy was an opportunist and a demagogue, but J. Edgar Hoover was truly psychotic.

Once the Inquisition began, the important question was no longer whether you were a communist. Rather it became whether you were not an anticommunist. If you dared criticize McCarthy, you became one of them. Throwing away the Constitution, the investigators employed snooping, accusing, and informing as they looked into civil service, unions, industry, universities, local school boards, and churches.

Sam Kanter organizes a union. Courtesy of Stan Kanter

Meanwhile, the Christian right was in its glory. It was hunting season, and all they had to do was accuse someone of being a communist, and he was a dead man. The truth had nothing to do with it. The FBI would come poking around, asking your neighbors about you, and before you knew it, your landlord wanted you out. It became so nuts that the YWCA and the Girl Scouts were combed for Reds. But for the victims of this witch hunt, there was nothing funny about it as civil liberties were abused and jobs—and sometimes lives—were lost.

Stan Kanter, who was born in June of 1938, grew up poor in Brighton Beach, his father a union organizer for the American Labor Party, his mother a secretary at the Communist newspaper, the Daily Worker. As a boy, Kanter attended a constant string of biracial union rallies or meetings at home at night in an attempt to bring better pay and safer conditions for the working man. Another of their causes was the end of Jim Crow, in America in general and in baseball in particular.

In the early 1950s the witch hunt for Communists, launched by Senator Joseph McCarthy, began to claim its victims. Communist Party officials, fathers of Kanter’s best friends, were jailed, accused under the Smith Act of undermining the U.S. government. Then one day Stan’s mother informed him that his father had “gone away,” on the run from the FBI. His father hadn’t really done anything more than organize unions, but under the Smith Act, he could be arrested, and he wasn’t taking any chances. He went into hiding, returning several years later, after the evil era of madness had passed. Before the witch hunt was over, 6.6 million people had been investigated. Except for the Rosenbergs, not a single case of espionage was proven in court. But despite the failure to find subversion, the Red hunt gave the appearance that the government was riddled with spies. The lives of thousands of men and women, including the Kanters and their friends, whose singular desire was the betterment of the poor and powerless, were left in its wake in shambles.

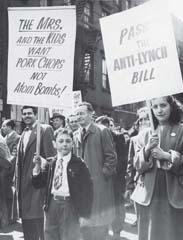

A young Stan Kanter pickets for peace.

Courtesy of Stan Kanter

STAN KANTER “When I was five, we moved from Manhattan to Brighton Beach. We lived in a condemned building. My father, who was often out of work, was a union organizer.

“Most of my young childhood memories were union meetings or rallies just about every night. My parents couldn’t afford babysitters, and I was taken to these things. If I was home, it was because there was a meeting at the house, thirty people I didn’t know, sitting around, talking.

“I was always taken to May Day parades, rallies, picket lines. As a little kid I was always walking around carrying picket signs.

“We really weren’t communists. We didn’t know about communism really until Joe McCarthy started talking about it. What my parents were were members of the American Labor Party. They believed in better working conditions, in workers’ rights. My father organized unions for people who worked in factories, where there were fires every day, always unsanitary conditions. He went around trying to organize.

“They also believed in equality of the races. At the union meetings at our home, half the people who attended were black. We all read Lester Rodney in the Daily Worker. Rodney had been championing getting blacks into the major leagues ever since he began his column. My father was an avid reader of Lester Rodney, and it became his cause too. Integrating baseball was also a cause the American Labor Party was pushing, and my father would take petitions around and speak on street corners. When Robinson was playing for Montreal, he would say, ‘We need Robinson in the major leagues.’ He’d attend rallies. We couldn’t have made phone calls. We didn’t have a phone. There’s a tremendous picture of my father and Jackie Robinson shaking hands on Jackie Robinson Day (September 23, 1947). He worked very hard to get Jackie into the major leagues, and so there was a picture of him shaking hands with Jackie at home plate.

Sam Kanter shakes hands with Jackie Robinson on Jackie Robinson Day, September 23, 1947. Courtesy of Stan Kanter

“When I was growing up, Brighton Beach was middle class. On one side is Manhattan Beach, which is ultra-wealthy. There were guards at every entrance and only doctors, lawyers, heads of corporations, and congressmen lived there. To the other side of Ocean Parkway was the Coney Island area, which was very poor, lower class, gangs and street fighting all the time, and in between was our Jewish middle-class area, very, very, very left-wing. The elementary school I went to, PS 253, had pictures of Paul Robeson hanging in the auditorium, and pictures of left-leaning author Howard Fast [he wrote Spartacus]. Kids would do reports on Fast’s books. They used to hold mock presidential elections, and in 1948 Henry Wallace [who was nominated by the Progressive Party] won in our school over both Truman and Dewey.

“Almost no one I knew had a car. We played in the streets all the time, stickball, punchball, and we never had to worry about a car coming. There were mothers looking out the windows. None of the other mothers went to work. We’d come home from school and go down into the street and play ball. We had almost no interaction with girls. We didn’t know from girls. The wealthy Manhattan Beach kids knew from girls, and the toughs who lived on the other side of us seemed to be hanging around with girls from the time they were nine years old.

“In the winter we played basketball at the after-school centers. We always got home at a respectable hour, when it was getting dark. Once a week we would be allowed to go to a neighborhood gym in the evening with a whole bunch of guys, and each mother approved. We had to go as a group to a home and say, ‘Can Eugene come with us to the gym today?’ ‘Yes, if he’s home by nine.’ And you’d be back on time. That was the kind of neighborhood it was, wholesome and nice.

“For junior high school I had to go into Coney Island. Half that school was Jewish kids from Brighton, who were walking to the other side of the tracks, and the other half was Italian street gang–type kids, who lived there. We could only walk to school if we all walked together, like thirty of us. When we got within two blocks of the school, we ran just as fast as we could, because there were gangs waiting for us.

“We didn’t have confrontations. You can’t call them confrontations. You would call it getting beat up. These were tough street kids. They wanted to fight. They enjoyed a good fight, and they found out quickly they couldn’t get a good fight out of us. Nobody would even punch back. We’d be crying and whimpering, so it didn’t even pay for them to beat us up. Most of the time we were so pitiful, they didn’t even bother. It wasn’t like they could rob us. We didn’t have any money. Nobody had lunch money. We had a little sandwich that they didn’t want. After a while, they said, ‘No point even harassing them anymore.’ But we still had to be careful. We didn’t dare go to school alone.

“I ended up becoming friends with some of these toughs. We played ball together in gym class, and they could see I was pretty good, and I ended up tutoring a couple of them, because I felt sorry for them, big galoots who were good athletes, but the math teacher would pick on them mercilessly, would really make fun of these Italian kids who knew from nothing and who liked the Jewish kids who knew the answers. I would help them with their math during lunch hour, and in return they would protect me from the other kids. So it worked out very nicely. When I got to Lincoln High School, it was the same situation. I never really got beaten up, because some tough guy would come by and say, ‘I know him. He’s okay.’

“I was not religious. My parents were nonreligious. We were well aware we were Jewish. We were very interested in a Jewish ballplayer, a Jewish comedian, a Jewish singer. My friends had bar mitzvah lessons. I went to shul a half hour a day to learn Yiddish, but it barely took. We were not kosher. We all went to Nathan’s to buy hot dogs. We could walk along the boardwalk to get there. My friends all ate them, whether they were kosher or not. But in their houses it had to be kosher. In those days the only restaurants were a Chinese, where we would eat chow mein, and a deli, where we could get a corned beef sandwich or frankfurters once in a while. Mothers made supper. I didn’t know from going out to eat until I got married.

“On special occasions—somebody’s birthday—we would go to Lundy’s in Sheepshead Bay. We didn’t have a car, but somebody always did, a relative, friends, somebody to get us there. Lundy’s was a huge barn of a place, where they served shrimp and lobster. There was no maître d’. You got there on a Sunday afternoon, the only time people seemed to go, and you stood over the table. You’d hover over a table and say, ‘It looks like they’re almost done.’ Every table had two or three families standing over who was eating, fighting. ‘We’re next. We’re next. We’re getting this table. Aren’t you people done yet? Come on.’

“The people at the table would say, ‘Get away. We’re still eating.’

“The waiters, who barely spoke English, were mean and hostile. It was a very hot place. There was no air conditioning. I don’t know why everybody loved to go there. But the food was good and inexpensive. You could get a lobster dinner for $3, with muffins and shrimp. It was a very special thing to go there.

“We moved many times in Brighton in those years. Basically, my parents could never pay the rent. Union organizing didn’t pay practically anything. And my mother worked at the Daily Worker as a secretary, and most of the time she didn’t get paid. We really had no money. They’d go seven or eight months without paying rent, and my father would just find another place and move a little closer to the ocean. At one point we lived with another family in a three-family house, and the guy who owned the house couldn’t afford to keep it anymore, and he offered it to my father and the other family who we were friends with. He said, ‘For a hundred dollars, you can have it.’ But nobody knew from a hundred dollars. Today it’s worth a million dollars.

“In that house we had two families living together in a one-family apartment. My parents had one bedroom. The other set of parents had the other bedroom. Two daughters from the other family slept in the living room. There was no bedroom for me, so I slept on the kitchen floor.

“I never resented it. I realized we were poor. I’m sure if my parents had money, we’d have lived better. I didn’t know any different. Most of my friends didn’t have any money. My friends’ fathers got up in the morning, went to the train several blocks away, came home late at night, ate dinner, lay down on the couch, and took a nap. In the case of my parents, they went to meetings. I didn’t know you were supposed to have money.

“We went to the movies on Saturday to see a film that took place in Hollywood—a fantasyland. It had no relation to us. There were two movie theaters in Brighton Beach, the Oceana and the Tuxedo, where you could get in for a nickel. They had double features and cartoons and shorts and newsreels and we’d get there about noon and stay right through the double feature. We went for the serials, and the deal was if you went to the first eleven, you got into the twelfth for free if you kept all the stubs. I would always get sick on the eleventh week. You could never hear the films, because there were hundreds of kids screaming in the theater. One week we went to see Go Man Go!, the story of the Harlem Globetrotters. The other picture was Seven Brides for Seven Brothers. We said, ‘Do we have to sit through this so we can see Go Man Go! again?’

“And we all got captivated. All these big studs were saying, ‘This picture isn’t half bad.’

“There was one other movie theater, called the Lakeland, which we called ‘the Dumps,’ because you could get in for about 2¢. The seats were all broken, and it smelled of urine. It was awful.

“There were two theaters in Coney Island, the Loews and the RKO, which were a little fancier. They were 20¢. That’s where the pictures came to first, but two weeks later they’d be at the Oceana and the Tuxedo. We knew to wait.”

More than for any other attraction, Kanter’s great passion was for his beloved Brooklyn Dodgers.

STAN KANTER “Before Jackie Robinson was Pete Reiser, who they said would have been better than Mickey Mantle. His first year he led the league in hitting. But he kept crashing into walls. He came out of the hospital with a concussion, couldn’t even walk, and Leo Durocher sent him up, and they deliberately walked him, even though he couldn’t lift his arms. Pete was on the team Robinson’s first year, and the two of them were just spectacular on the base paths.

“I remember the first time I saw Jackie Robinson play. I couldn’t believe any athlete could be that exciting. Did you ever see him in his early days?

“Pete Reiser would be on third base, and Robinson would be on first, and Robinson would deliberately leave the base, and they’d have to throw over, pay attention to him, and he’d stay in the rundown until Reiser could score—and most of the time he got out of it. It was phenomenal watching him.

“And Robinson would steal home. Whoever saw anyone steal home? I always got taken to Pirates games, because Ralph Kiner, who hit home runs, was a big attraction. I saw the Cubs with Hank Sauer and Frankie Baumholtz, and the Giants, who had big, lumbering guys. Robinson was the first real runner.

“I loved Duke Snider. He had the most graceful swing I ever saw. We liked to watch him miss as much as connect with the ball, because his whole body wound up, an amazing swing. He was also a graceful outfielder, climbing the fences.

“Snider was a terrifically nice person, and in left field a lot of times we had Cal Abrams, who was Jewish, so you really cared about him.

“There was a TV show before the games called The Knothole Gang. They would have three kids out in the field trying out. A Dodger would hit balls to them, and then pick which kid was the best. No matter what Dodger was there, he was so nice and friendly and wholesome. You could admire any one of these guys and say, ‘I would like him to be my father or pal.’ There wasn’t one who was arrogant or stupid. Now you watch interviews with ballplayers and you say, ‘My God, I wouldn’t want to be in a car with this guy for ten minutes.’ Every Dodger seemed so nice, and if you ever saw one of them outside the ballpark and asked for an autograph, it was the same thing. ‘Hi kid, how are you doing?’ ‘How are you doing, Duke?’ They always smiled. They were always nice. Cox was a little bit sullen and withdrawn, and Furillo wasn’t a great outspoken guy, but Reese, Hodges, Snider, Abrams, and Campanella were nice, warm people, and most of them lived in the neighborhood. You knew that Gil Hodges lived on Bedford Avenue. People saw the players shopping for groceries, working a part-time job at a gas station. In those days they weren’t multimillionaires, above the fans. They were just nice people who were terrific athletes living in the neighborhood. This was a team you could really root for. The Yankees, of course, were U.S. Steel. We hated them.

Stan Kanter listens to Red Barber on the radio. Courtesy of Stan Kanter

“During the World Series, when I was in elementary school, we sat in the classroom, and they piped in the game over the loudspeaker. Whenever the Dodgers were in the World Series, which was about every year from 1947 to 1957—we missed 1948, 1950, 1951, and 1954—we’d sit in class and listen to the games, and then at three o’clock, when the bell rang, we’d go, ‘Oooh, we’re missing a pitch.’ You’d leave school and walk home. Dodger games were always on the radio, and as we walked home from school, we’d hear it coming out of every window. It was early October, still pretty warm, and there was no air conditioning in those days. People had their windows open. When you got home, you listened to the end of the game.

“I was home by the time Bobby Thomson hit that home run in the final game of the 1951 season. The Thomson home run was not a happy thing. I remember all of us walking out into the street and sitting on stoops quietly, nobody talking. It was sad.

“I didn’t blame Ralph Branca. Not at all. No. This was a team you rooted for. Nobody ever felt anything negative, not that I know of. None of my friends. We never thought anything negative about anything the Dodgers did. Losing to the Giants that day wasn’t so terrible. Although the Giants were our rivals, they were a National League team, and they played fair. See, the Yankees weren’t and didn’t. Every year at the end of the year the Yankees would wrap up their pennant with a month to go, because there was no competition in the American League. The Dodgers were fighting the Giants, the Cardinals, the Phillies, and they’d go down to the last day, and they’d enter the World Series with their pitching staff spent. One year they started Joe Black, a relief pitcher, in the first game, because no starters were available. The Yankees would be rested for three weeks. They’d have their rotation in order. They would buy National League stars, pick up terrific players, to help them in the Series. They bought Ewell Blackwell, Johnny Mize, Enos Slaughter. Their payroll was always much higher, and these guys would make a difference in the World Series.

“The Giants were like the Dodgers. We didn’t want to lose to them, but I loved Willie Mays, a tremendous player. Stan Musial was an all-time favorite, even though he was an opponent. I liked Richie Ashburn and Robin Roberts from the Philly team. I didn’t feel bad losing to those guys. The Yankees, who were an all-white team, were the one team I could never root for. I rooted against them—always. I didn’t feel horrible if the Giants, Phils, or Cards would win. It was just the Yankees. I knew they were going to the World Series. So I didn’t feel horrible about Thomson. If you remember, the slogan in Brooklyn was, ‘Wait ’Til Next Year.’

“My mother worked at the Daily Worker, which was not a mainstream newspaper. It was the paper of the Communist Party. In those days there were twelve daily newspapers in New York City. Most of the kids read the Daily News and the Daily Mirror. There was also the Times, the Post, the Journal-American—which was always right-wing, the Herald Tribune, and the Sun, plus the Compass, the Brooklyn Eagle—plenty of newspapers. Those papers, which were owned by capitalists, were always attacking unions, attacking the Daily Worker, attacking anything that was leftist. If workers went out on strike, every editorial in the city supported the corporations, and the workers were thrown in jail. The Daily Worker was the one paper saying, ‘No, the workers are right. They deserve raises and better working conditions.’ It was in the best interest of the other papers to give a black eye to the Daily Worker, badmouth it all the time. It wasn’t a crusade, but if you were a reader of the other papers, you would come across the line ‘that left-wing rag, the Daily Worker,’ and people were just going to have a negative opinion of it, which was so hard to understand. When I became a teacher, I noticed that every black teacher I worked with read the Daily News. I said, ‘All of their editorials are antiblack. Why do you read this paper?’ They said, ‘I know. I know. I like the sports section. My mother likes it.’ It was hard to understand. They should have been reading the Daily Worker instead. I have friends who are teachers today, who vote Republican, and I say, ‘You’re so interested in health care, and the Republicans are doing everything to destroy health care. Why do you vote for them?’ And they turn a deaf ear.

Sally Kanter was a secretary at the Daily Worker. Courtesy of Stan Kanter

“So the Daily Worker was not a paper you wanted people to know you had in your house, even before McCarthyism came in. My mother would get Knicks tickets under the basket for me and my friends from Lester Rodney, the Daily Worker’s terrific sports reporter. My friends would have been appalled to know how I was getting them. Since I kept getting Knicks tickets from Lester Rodney, I told him once, ‘I’d like to cover the games.’ I wrote one up, and he printed it in his column. He just wrote, ‘By Stan.’ But I couldn’t tell any of my friends I had written a column in the Daily Worker. I was shocked the next day when one of my teachers came over to me and said, ‘I saw your column in the newspaper. I’m very impressed.’ I thought, There’s a teacher in my school who reads the Daily Worker! I can’t believe that. But none of my friends ever knew. Nobody knew. Years later my closest friend, Ernie Brod, was on the Columbia Spectator, and he was assigned to do a story about something happening at the Daily Worker, and he called, and my mother answered the phone. He said, ‘This is Ernie Brod from Columbia,’ and she almost blurted out, ‘This is Sally Kanter. How are you, Ernie?’ It would have been quite a shock to him. I never let my friends in the neighborhood know.

“None of my friends from Brighton ever knew from blacks. There was one kid in our elementary school, Michael Gordon, who was black. So they didn’t know from black people. But every summer I went to interracial camps.”

Kanter was sent by his parents to a union-sponsored summer camp in upstate New York’s Catskills Mountains on White Lake, called Wo-chi-ca, which was shorthand for Workers’ Children’s Camp. The ideology dictated that since children were the future leaders, summer camp would be a perfect place to instill in them core values. The goal was to prepare these children to be leaders in the fight for peace, civil rights, and social justice. To the townspeople, these kids were dangerous Commies and subject to attacks. In an attempt to lower the animosity, the name of the camp was changed from Wo-chi-ca to the less-threatening Wyandotte.

STAN KANTER “I went there for two weeks for several summers. The first year I went there I was put in a bunk with several kids whose fathers were the first Smith Act victims. Bill Gerson’s father was Sy Gerson. There was Fred Jerome and Pete Berry, and half of the fourteen kids in my bunk were black, and I became friends with them.

“When I first went to camp there, I was shocked at how much more my camp friends knew than my neighborhood friends. Most of the kids in the neighborhood had never been out of Brooklyn. They might have been to Manhattan once in their lifetime to see a show. Most of these kids from camp lived in Manhattan, and they had been all over, to California, to Canada, even to Europe, and they knew about everything. They read newspapers and magazines I had never heard of. They were so much smarter. They were really bright, won awards, went to Cooper Union or Columbia. They were really bright because they had grown up reading. My friends who I met in camp knew about everything that went on in the world.

“During my teens I led a double life in the afternoons. I had my neighborhood friends, and every once in a while I’d get on the train and go to Manhattan, and meet my camp friends. The group was called the Young Communists, but we weren’t Communists. It was the Labor Party youth group.

“I would have to come home to the neighborhood and really tone it down. A teacher would ask some questions about Russia, and I would know everything going on in Russia, but if you seemed too knowledgeable, it would be, ‘What are you, a communist or something?’ So I had to be careful in school, even in having conversations with them. I couldn’t seem too knowledgeable. ‘How do you know all this stuff?’

“Later on I worked as a busboy at a place called Camp Unity, which was run by the labor unions but which had the reputation of being a communist camp. A lot of the blacklisted actors worked up there on the entertainment staff. Pete Seeger was the resident folk singer. My friend Bill couldn’t stand him, because he used to hold his concerts on the basketball court when we wanted to shoot baskets. We had constant battles with him.

“Paul Robeson was always at the camp. The Peekskill event [where he was pelted with rocks by “patriots”] was really big in our family. My father had gone up there and gotten pelted with stones. Most of the people who met in our house had been there, and they had rocks thrown at them, and their car windows were smashed. At the camp Robeson would sing “Old Man River,” and songs by the Weavers, who used to perform there. They were such nice people. They cared about people. They cared about the workers. They cared about equal rights for people. Women’s rights. Medical insurance for people. And for them to be blacklisted…they were such good guys. It was a pleasure to listen to them.

“Hesch Bernardi [actor Herschel Bernardi, who was blacklisted in the 1950s] was a wonderful person. I was a kid, and he was a grown entertainer, but he knew the busboys and waiters weren’t getting much to eat, and he’d say, ‘Come to the canteen. I’ll buy you a sandwich.’ Lorraine Hansbury, who wrote Raisin in the Sun, was on the staff. Lionel Stander with that gruff voice and Les Pyne were there too as was a guy named Paul Draper, who was the best tap dancer I ever saw.

“It was at the camp that I was introduced to jazz, which wasn’t popular in my neighborhood. Back home everyone listened to Perry Como and Eddie Fisher, but at the camp there were black entertainers, great jazz musicians, and these guys would play all day long, rehearse for hours. I fell in love with the trumpet. Jazz concerts were held almost every night. They were terrific. And then I would go back to my neighborhood, where kids didn’t know from anything.

“‘Where were you?’

“‘At the camp.’

“It was during my junior high years that we started getting visits from the FBI. My parents would be out working during the day, and every once in a while the doorbell would ring, and two FBI men would be there asking questions.

“‘What time will your father be home?’ I was told never to answer anything. ‘I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know.’ My father would come home, and I’d tell him, ‘Two FBI guys were here.’ ‘Did you tell them anything?’ ‘No. All I said was, “I don’t know.”’ ‘Why did you tell them that?’ Whatever I said, he would say, ‘Why did you tell them that?’

“We got this every few days, and they would interview neighbors in the building, and this was another reason we would have to move, because the landlord would say, ‘The FBI guys keep coming here and bothering me, and they say you’re a communist. Why am I allowing you to live here?’

“The landlords were sympathetic, because they were working-class Jewish people, but after a while they would start to get scared. I wasn’t privy to all the conversations, but I gather they would say to my parents, ‘Listen, I really don’t need this anymore. See if you can find another place.’

“I didn’t care. I figured, If you have to find another place, you move. And we were moving in the same neighborhood. I kept the same friends. It wasn’t like I was living in a beautiful room in a beautiful house to begin with. All we had were books, which most people didn’t have, and we always took the books.

“I attended Lincoln High School, which was probably the best high school in the city. We had an incredible teaching staff. They were the top teachers in their field, and they kept winning citywide awards. Joseph Heller came out of there, and Arthur Miller. Our senior class president, Louie Gossett, was appearing on Broadway in Take a Giant Step. Neil Sedaka had been a classmate since we were in the second grade. I’m probably the only kid who never beat up Neil Sedaka. They’d say, ‘Let’s beat up Neil.’ I’d say, ‘What are you going to beat up Neil for?’ Neil Diamond was a classmate. The principal of Lincoln was very interested in theater, and they would put on shows! Our star basketball player was Mark Reiner, who we thought was one of the greatest players of all time, but he went to North Carolina as the only Jewish ballplayer, faced anti-Semitism, quit the team, went to NYU, and was never the same. Our football team won the city championship, and many of them were all-city players, but none of them became famous. They didn’t go to the pros. They were Jewish. They used football to get into college, to pursue their studies. I graduated in 1956.

“Around the beginning of my high school years, McCarthyism started to take flight, and it became a very unpleasant situation, because you couldn’t even say the word ‘Russia’ in a classroom. ‘Does anyone know where Russia is?’ If you raised your hand, everyone said, ‘He must be a Commie. He must be a Commie.’ Russia was a dirty word. To us, it was the Soviet Union.

“Once McCarthy started appearing on TV, talking about Communists infiltrating the government, the army, the country, things got worse. When the first Smith Act trial was held, twelve defendants were accused of conspiring to stage a violent overthrow of the government. As I said, a number of these men were my friends’ fathers. One of them, Fred Jerome’s father, was a little rabbi scholar type, a man who never raised his voice, who wouldn’t step on an ant. If a fly came and someone said, ‘Swat that fly,’ he’d say, ‘No no, you don’t kill things. You don’t hurt things.’ They were all that way. I’m thinking, The violent overthrow of the country by these people?

“The one who wasn’t like that, Sy Gerson, was a big, strapping guy, a war hero, an athlete, who ran for office and got elected to the city council. His campaign was, ‘Peace, prosperity, and a pennant for the Dodgers.’ Sy was cut loose from the other eleven because he had been a war hero. Bill Gerson and Fred Jerome were my closest friends, and their fathers were on trial. After school, I’d take off and go down to Foley Square in Lower Manhattan and watch the Smith Act trials. It was amazing, watching the prosecutor point at these people saying, ‘They are trying to overthrow the government by violent means.’ I would look at them and think, All they know from is how to read. They were such quiet little types.

“After they were put in jail, they started to have hearings in Hollywood. People all over were being thrown into jail, including a distinguished teacher from my sixth-grade class. Everyone wanted to be in his class. One day he suddenly disappeared. I asked, ‘Where’s Mr. Lipschitz?’ ‘He isn’t coming into work anymore.’ I found out afterward he had been arrested after he was asked to give names, and he wouldn’t. Suddenly people were disappearing all over the place.

“I can’t say my father felt any pressure about losing his job when McCarthyism heated up, because he never really had a good job, and we never had much money. The union wasn’t going to get rid of him, because he was working for practically nothing. The Daily Worker wasn’t going to get rid of my mother. They weren’t going to lose their friends, because their friends were other left-wingers. Although friends started to disappear. They would go into hiding. I do remember one of my uncles wouldn’t come over because he didn’t like my parents’ politics. So life didn’t change much—until my father didn’t come home one day.

“My mother said, ‘Dad has to go into hiding. They are arresting people, and for his own good, he has to disappear.’ The fathers of my close friends were in jail. Suddenly I didn’t see some of the left-wing fathers of my other friends. Mothers began running the houses. At this point my grandmother came to live with us. My mother was out working, and my grandmother did the cooking, if you call it cooking. Reheating leftovers was more like it. I was older, and I had to take care of my younger sister, walk her to school and pick her up after school and get an after-school job, because we needed money in the house.

“I wanted to be president of NBC, but I couldn’t get that one so I worked in a candy store, in grocery stores, delivering, stocking groceries, crummy, low-paying jobs. I had to deliver milk cartons to school. We used to get free milk, little, teeny cartons of milk, which would sit all day in school until milk time, at which point the containers were all warm and the wax would drip into the milk. I carried these huge cartons to the school, a five-or six-block walk, because we didn’t have bikes or cars.

“I never kept the money. They were very low-paying jobs, and I gave the money to my parents. When I had a summer job, working as a counselor or busboy, the arrangement was to mail the money home to my parents. We lived on allowances, and the highest I ever got was a quarter a week. But what did I need? A notebook every year. My parents took me to buy clothing and sneakers. Books we had in the house, and I went to the public library all the time. I didn’t buy records. We didn’t have that in those days. So I didn’t need much money, just some school supplies, and it was the same for all my friends, which is why we weren’t dating. We didn’t have the money to spend on girls.

Sam Kanter. Courtesy of Stan Kanter

“We didn’t know we were poor, because there were poorer kids in Coney Island. You would walk through there and see really broken-down hovels. We lived what we considered a middle-class life. We were living in two-family houses as opposed to tenements. It didn’t seem bad.

“During the time my dad was away, anywhere between three to five years—I’m really bad with time—I didn’t see him more than a half dozen times. It was like out of a movie. I would be given instructions what to do: we’d get on a train at the Brighton Beach station, get on the express train, get off at the next stop at Sheepshead Bay, and both the express and local would be standing there on opposite sides of the platform. We would stay on the platform until the last second, and we’d hop on the local. We kept changing cars all the way to Manhattan, making sure no one was following us. We’d take a bus somewhere, get off where they told us, wait on a corner, and someone would pick us up in a car and drive us somewhere. I have no idea where. Seemed to us like upstate New York.

“We would get out, and another car would take us somewhere remote in the country. My father would walk out of the woods, give us a hug, and say, ‘How is everything?’ We’d talk to him for two minutes, and a car would come and pick him up. It seemed ridiculous.

“When I was working at the camp, once or twice we made the same arrangement. Someone would say, ‘Come with me. Get in the car.’ And he’d drive somewhere up a hill and around winding roads, and I’d get out, and another car would come and take me. I’d get out, and my father would come out of another car, and we’d talk for a few minutes.

Stan Kanter today. Courtesy of Stan Kanter

“I found out years later that in the last year of his hiding he was staying with very wealthy friends on Bedford Avenue and Avenue M. I had once babysat there. I loved it, because that house had beautiful rooms and beautiful Heritage books. The kid would watch television, and I could watch too. While my dad was living in this millionaire’s house, we were living in Coney Island in a slum, a fifth-floor walk-up, the only white people on our block, because we couldn’t afford Brighton anymore. Before that, he never told me where he was living. He was on the move a lot, just to keep from getting arrested. During that period the FBI kept coming to the house. ‘Have you heard from your father?’ It’s conceivable they never would have arrested him. I don’t think he was that important a person. But he didn’t want to take the chance. Same thing with several of my other friends’ fathers. They didn’t want to take the chance, and they went into hiding.

“Things started to get better when McCarthy was finally revealed to be the fraud he turned out to be. I watched while Edward R. Murrow challenged him, and then at the army hearings, Joseph Welsh, the army lawyer, went after McCarthy, exposing him, and that brought tears to everyone’s eyes.

“To me and a lot of people, McCarthy really was evil. I had been a great fan of John Garfield. Body and Soul had been on the Million Dollar Movie, on Channel 9 in New York. They showed the same movie every night for seven nights. I watched that every night. It was a sensational movie, and McCarthy drove Garfield to his death. He wrecked a lot of lives.”