WHEN YOU TALLY THE DAMAGE INFLICTED BY JOSEPH MCCARTHY and HUAC, you could argue that compared to the 20 million Russians Stalin killed, the purge victims in America got off easy: a few foreign-born socialists were deported, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were put to death, about 150 people went to prison for a year, two years at the most, and perhaps 10,000 others lost their jobs.

As in 1940, when the Rapp-Coudert Committee targeted Jewish teachers, ten years later HUAC came back for a second shot at them. Never mind that this was supposed to be a nation that cherished academic freedom or that someone’s political activity away from the classroom should have had nothing to do with his ability to teach. The way Joe McCarthy and HUAC witch hunters defined it, anyone who had been a member of the Communist Party or who refused to testify before his committee had surrendered the right to teach.

The Senate tried to stop McCarthy in June of 1950, after his scattershot charges about Communists in the State Department. Congressman Millard Tydings issued a report on his charges, calling McCarthy a “fraud and a hoax on the Senate.” But McCarthy, before seeing the report, undermined the findings by saying any such report would be a “disgrace to the Senate, a green light for the Reds.” When McCarthy pushed on, making more undocumented charges, he was backed by the Christian right and by Republicans wanting to give President Harry Truman and the Democrats a black eye. In the next Senate election, Democrat Millard Tydings was beaten in Maryland. The winner, John Butler, had received a potful of money from McCarthy’s rich oilmen backers. As part of the campaign, Butler’s henchmen displayed a doctored photo of Tydings standing with Earl Browder, the former head of the Communist Party. Karl Rove would have been proud.

McCarthy never let up. Every day he demanded Truman be impeached and Secretary of State Dean Acheson be fired. For the next four years McCarthy poisoned America’s air, turning this country into everything he said he feared. The only person who could have stopped him, Dwight Eisenhower, Truman’s successor, decided for political reasons it was best to remain quiet, a mistake he would later regret.

What was notable was that before the Communist witch hunts began, many of the teachers who were later fired—teachers who had been teaching for years—had never been accused of recruiting students or teaching the party line. Most had been active Communists in the past, but after they realized that Stalin was a monster and that the Soviet Union held no panacea, their pro-Communist political activity had waned. None of that mattered to HUAC or to Senator McCarthy, whose boldness seemed to grow along with his notoriety.

Most of the firings came after a target exercised his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. With the nation gripped in fear of Soviet domination, the courts allowed the Wisconsin demagogue to suspend constitutional protections.

The ordeal usually came in two stages. First a representative from an official agency, such as a school superintendent, would investigate, followed by a hearing in front of McCarthy. Splitting the job made it easier for the school superintendent to shun responsibility for a person’s dismissal. He could rationalize his actions by saying that McCarthy had ordered the firing.

Once someone was fired, the victim stayed fired. The victim’s name remained on a blacklist that everyone denied existed, and getting another job in the field—or even in another line of work—became almost impossible.

Terry (Ted) Rosenbaum, whose mission in life was to teach high school students the joy of learning, was one of the victims of McCarthyism. He was fired in April 1954, and he would not be vindicated until 1972, when the United States Supreme Court ruled that a person could not be fired for taking the Fifth Amendment. Rosenbaum would get benefits and his pension for the years he taught, but he could never again get back what he had lost: his life’s work. He became a fund-raiser for the Educational Alliance for a children’s hospital on Long Island. To his everlasting credit, Ted Rosenbaum found a way to do good for others, despite his ordeal.

Ted Rosenbaum was born with the given name Terry in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn on February 7, 1918. His father, a baker who came from Poland, arrived at Ellis Island at the beginning of the twentieth century, in the wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. He met his wife in Brooklyn, and they had three children. Spurred by their mother, Terry and his siblings all had top grades in high school, and all graduated from college. Terry’s goal in life was to teach American history, and he was well on his way to a brilliant career, when his civic activities on behalf of black citizens attracted McCarthy’s attention.

The incident that put him directly in McCarthy’s gun sight occurred in Brooklyn in 1951, when Henry Fields, a black man driving carelessly, scraped a parked car. The owner of the parked car, furious, summoned the police, who chased Fields five blocks in a squad car and after cornering him ordered him out of the car. Fields turned, and, without provocation, the policeman shot him three times in the back.

The blacks were furious and threatened to riot. Rosenbaum, a popular community leader who four times had run for assemblyman on the American Labor Party ticket, was known for his connections to the black community. In the early morning, he went to the police station to help ease tensions.

Not long afterward the superintendent of the New York City public schools called Rosenbaum in for a meeting, and so did Senator Joseph McCarthy. There had been complaints about his behavior. When Rosenbaum asked what he had done, he was asked, “Are you a member of the Communist Party?” Rosenbaum wasn’t, in fact, but his knowledge that the Constitution protected him from having to answer such a question emboldened him. He told the superintendent it was none of his, or anyone else’s, business. When he was called in personally by Joseph McCarthy, he told the senator from Wisconsin the same thing.

Rosenbaum’s license to teach was revoked, and he would have to wait eighteen years before the Supreme Court ruled that his job—and all those people whose jobs had been taken away after Smith Act convictions—had been taken from him illegally and unconstitutionally.

Unable to find work of any kind, Terry Rosenbaum changed his name from Terry to Theodore, and he spent the rest of his life raising money for charitable organizations. In addition to his livelihood, the loss was also borne by the hundreds of high school students denied the opportunity to learn from his inspired instruction.

Nettie and Abe Rosenbaum married in 1916 and lived their entire lives in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Courtesy of Ted Rosenbaum

TED ROSENBAUM “My father left Poland because life for Jews was made unbearable there. He was discriminated against in all sorts of ways. The jobs he could hold were limited. His income was limited. He was a baker who worked very hard, but he made a bare living. He told me about the pogroms, where Cossacks would ride into his town and murder Jews. Life was very uncomfortable there. Every time he thought about his past, tears would come to his eyes.

“His brother had come to Brooklyn a couple years before, and he came too, and he had a tough job earning a living. He finally got a job as a baker, and he met my mother through mutual friends who knew my mother’s family. They were introduced, and they got married.

“My mother also was Jewish, but she was not an immigrant. Like so many other Jewish mothers and fathers, but mostly mothers, she made sure her children were going to get an education. That was their way to liberation. ‘You have to get good marks,’ was all we heard.

“I was the oldest of three children. I have a younger brother and sister. All three of us graduated from college, because she was on our backs every single hour of every day. I can never forget it. One day when I was in the fifth grade I came home, and I said, ‘Mommy, I got a ninety-eight on my report card.’ She looked at me, and she said, ‘What happened to those other two points?’

“I went on to get a master’s degree at Columbia; my brother, Lloyd, became a professor at MIT [Lloyd, denied employment as a professor because of anti-Semitism, changed his name to Lloyd Rodwin. He went on to become the chairman of the Urban Studies program at MIT], and my sister graduated Brooklyn College and also had a career working for various businesses. She was very competent.

“Brownsville was a poor, poor working-class area. It was 85 percent Jewish and 15 percent black. The main shopping street was Pitkin Avenue. On both sides of the street there were stores: shoe stores, clothing stores, candy stores, restaurants. On weekends all the working people came there to shop and eat, and on certain streets pushcart peddlers sold all kinds of things. It was very rich culturally.

“There were synagogues all over the place. We did not belong to the synagogue. My father and mother were atheists, and I was too.

Twenty-eight year old Terry Rosenbaum and his parents, Abraham and Nettie. Courtesy of Ted Rosenbaum

“We played punchball and stickball and handball in the playgrounds, and basketball. We played stickball in the streets, using broom handles for bats. We were rabid Brooklyn Dodger fans even though we couldn’t afford to go to Ebbets Field.

“I went to Samuel J. Tilden High School. It was a good school located just outside of Brownsville. Fortunately I was able to walk there, because it was not easy for us to pay for buses. I graduated in 1932. I was young—fifteen. My mother was always on my back, and I skipped several grades. From one point it was good for me, but from another, I was always the youngest, youngest, youngest in the class, and it made life socially more difficult.

“I was three years younger than the other students when I enrolled at City College. In my day CCNY was the top of the pyramid. The school had a terrific reputation, and getting in was something. I got on the subway every morning, and I rode for an hour and ten minutes to get from Brownsville to the 137th Street station in Manhattan. And I’d return home the same day. I did my studying on the train. I was a big guy with long legs, and people would trip over my legs while I studied.

“I wasn’t involved in any politics there. I went to classes, and after school I worked at the Thom McAn shoe store on Pitkin Avenue. We were a poor family. I didn’t have much spare time.

“After I graduated from CCNY, I went to Columbia University, where I got a master’s degree in history. My goal was to be a teacher of American history in the New York City high schools. Which I did. I loved teaching.

“You had to search around for placement until you got your teacher’s license, and my first job was in the East New York Vocational School. I walked in there, and I’ll never forget, the kids’ attitude was: I’m learning auto mechanics and similar trades, why do I need this?

“They even said it to me. One kid told me, ‘My mudda sent me here to loin a trade. Why are you giving me this goddamn history?’

“It wasn’t one or two kids. It was in general. And it devastated me. I had just come out of college, and I was going to be a teacher, make young people interested in American history, and then this. I can’t tell you how devastated I was.

“I was there about two weeks, and I thought, I have to make a decision. I have to prove to these kids that learning American history is vital to their future.

“I took a week off and prepared a series of lesson plans, the title of which was ‘Why History Is as Important to Me as My Trade.’

“I came into class, and I said to the class, ‘I’m going to be a lawyer for the defense, defending my subject.’ And for a week I gave them lessons. I gave them simple concepts. I said, ‘You’re an auto mechanic. There’s a depression, and you can’t earn a living. Or you don’t have money to buy things. Or your job is menaced. Your wages go down.’ Or, ‘You say to yourself, “Why do I care about the farm problem?” Because farmers, when they’re poor, they can’t buy, and when they can’t buy, your job is menaced. Or you get lower wages.’

“I went down a whole list of things, and at the end of the week I turned to them, and I said, ‘You’re the jury now. I gave you my case. How do you feel about this? Am I right or am I wrong?’

“Some of the kids were crying. ‘I didn’t realize,’ they said. It was the greatest thrill of my life. A couple of years later [April 14, 1953], one of those kids was a sergeant in the army in Europe, and the New York Sun had pages on education, and my former student wrote a letter and in it he said, ‘I had a teacher, Terry Rosenbaum, who taught me American history. He made me understand why it’s important (I get tears when I talk about it), so I always wanted to join the army, because I felt as though it was my duty as an American. There is one thing Mr. Rosenbaum made us learn, and that was the heart of the Declaration of Independence. I’ll always remember it, as long as I live.’

“I taught for close to a year, and then I transferred to Samuel J. Tilden High School, where I had been a student. It was a very special feeling to work there. I taught there for eleven years.

“I loved teaching. I loved teaching history. I must say I was very popular with my students. They could feel my interest in history and my enthusiasm and my willingness to interact with the students, getting their opinions. Those were fruitful years, except they didn’t last too long.”

Rejected by the army because of bad ears, Terry Rosenbaum did his patriotic duty by raising money for the war effort. Away from the classroom, he also became an active member of his community. His first civic act was to expose a New York City patrolman who was distributing anti-Semitic literature. He then became chairman of the Brownsville CIO Community Council and the legislative director of the Brownsville Neighborhood Council. He was also cochairman of the Brownsville Red Cross Drive.

He joined the American Labor Party because, he says, it was the only party at the time interested in the health and welfare of poor working folk. It worked on campaigns relating to rent control, minimum wage, more library facilities, and better working conditions, and in 1944 he was asked to run for the New York State Assembly.

TED ROSENBAUM “The American Labor Party was pretty strong in Brownsville. I liked what it was doing, and I became active. Various members of organizations, both Jewish and black, came to me and asked me to run for the assembly, which was the farthest thing from my mind. At first I wasn’t sure if I should do it when they asked me to run, but it occurred to me that one of the best ways to promote the issues, rent control, price control, discrimination, was to get active in politics, so I agreed to run. I felt so strongly about the issues in those days with the war on. Working-class people were taking an awful licking, so I became a candidate, and I ran four times.

“The American Labor Party was the only party interested in helping the working class. The Republicans, just like today, were just reactionary. The Democrats were supposed to be the liberals, but when it came to action on issues—better schools, discrimination—they did much better than the Republicans, but in terms of real action in the community, they did nothing of consequence.

“Helping in my community is what turned me on. I worked very closely with the black community, with black leaders like Justice Hubert Delaney, who was a justice of the domestic relations court, and with dozens of black ministers. The black community needed jobs. They needed tenant rent controls and rights. Many of them were unfairly evicted. Our party represented not only the blacks, but poor whites as well, but we especially fought for black rights. I don’t want to exaggerate our influence, but at the time Jackie Robinson came to the Dodgers, we had helped create an atmosphere of tolerance in Brooklyn.

“I had no expectation of winning but at least it gave us an opportunity to raise the issues and verbalize them and bring them before the public and debate them, and that was something I relished, because it was our way of getting our issues on the public agenda.

“It was part of the movement generally in those years to liberalize the Democratic Party, and in that sense it was successful. If we hadn’t raised the issues, no one would have. That’s why a third party can serve a useful function, so long as it doesn’t help the most reactionary people get and keep power.

“The only American Labor Party candidate ever to win was Vito Marcantonio [New York State congressman from East Harlem, 1935–37, 1939–51] in Manhattan. What a guy! He thought very highly of me. I did very well, and two years later, in 1948, I ran, and the Democratic candidate, Alfred Lama, was so scared because I was quite popular, that they got the Republican Party and the Liberal Party to endorse him. He had three lines on the ballot to my one line.”

He sings:

Terry Rosenbaum, ALP,

Cast your vote for democracy.

There’s a man in this community,

Who fights for victory, unity.

Send him up to Albany!

Vote for Terry Rosenbaum.

Rosenbaum’s life proceeded as planned until a fateful day in 1951, when in the middle of the night he was called to go down to the police station to help quell a disturbance.

TED ROSENBAUM “My wife and I had attended a family gathering in New Jersey. We went to bed, and I was awakened at one in the morning by a phone call from Max Gilgoff, a teacher colleague of mine who worked with me in the American Labor Party. What a guy!”

Gilgoff, like Rosenbaum, was a teacher and a community activist. Gilgoff was chairman of the East Flatbush Child Care Center, which he organized to help working mothers during the war. Gilgoff and Rosenbaum together had organized a community service to help people who had landlord and welfare problems.

TED ROSENBAUM “He called to say there was a near riot in Brownsville. A twenty-six-year-old black father of four had been shot and killed by a cop. He was driving and apparently turned the corner and nicked a parked car in front of a grocery store and kept going. The owner of the car came out and called a cop, who was nearby, and the cop chased him in his police car five blocks, and with people sitting out on their stoops in the street—in those days that was their way of getting sunlight and fresh air—the cop swung in front of Henry Fields’s car, backed up, got out of the car, pulled a gun, and ordered him out of the car. Fields was so shocked when he saw the cop with the gun, he turned away, and the cop shot him three times in the back and killed him.

“It hit the press the next day, and the black community went nuts, as you can understand. That’s why the black community besieged the police department that night, and why my friend called me, because he knew I was well respected by the ministers. I went to see what I could do to pacify the situation. I ran down there at two in the morning, and it was really a hell of a scene. I led delegations to the police department and to the mayor of the city of New York, protesting against this terrible thing. We didn’t want this incident to serve as a role model for other cops.

“Not long afterward I got a letter from Dr. William Jansen, the superintendent of the board of education of New York, to come down to his office. He had gotten reports I was doing terrible things in the community.

Terry Rosenbaum presented a challah to Paul Robeson. Robeson campaigned for Rosenbaum when he ran for the New York State assembly in 1948 . Courtesy of Ted Rosenbaum

“I came down, and after he asked me a few questions about the Fields case, I told him, ‘Look, I am a teacher of American history. You’re a superintendent of schools. One of our obligations is to teach our students the value of democracy and to practice what we preach. That’s exactly what I did in this horrible incident. And you’re calling me in?’

“‘I got letters of protest,’ he said.

“‘From whom did you get them?’ I asked.

“‘Are you a member of the Communist Party?’ he asked.”

Rosenbaum was not, but so what if he was? The question offended him greatly.

TED ROSENBAUM “I said, ‘You called me down about the Fields case. Here’s your letter. Why are you asking me if I’m a Communist? What does my political position have to do with anything? I’m not answering such an unconstitutional, illegitimate question.’”

He was told to expect another letter. It came in November of 1953, and this time he was ordered to appear before Senator Joseph P. McCarthy, who was on a witch hunt to oust suspected Communists he contended were plotting to overthrow the government from such disparate places as the federal government, Hollywood, and the army. His target at the time Rosenbaum was called was army personnel at Fort Monmouth in New Jersey. In that Rosenbaum had never been an employee of the federal government, he was perplexed as to why McCarthy, who stood for everything Rosenbaum abhorred, was calling on him to testify.

TED ROSENBAUM “McCarthy voted against almost every law that would benefit the average American: housing, schools, hospitals, laws against discrimination. He has opposed the truce in Korea. He was supported by almost every anti-Semitic and anti-Negro group—who have made him their hero. He has sabotaged the Bill of Rights more than anyone in our history. So you see that McCarthyism hurts all the American people. Therefore, like Hitler, to scare people, he calls anyone who disagrees with him either Communist, pro-Communist, a tool of the Communists, or a ‘Fifth Amendment Communist.’”

At the time Rosenbaum was called, McCarthy was holding hearings in New York on the army. Rosenbaum said to himself, I was never a member of the army. What the hell does he have to do with the board of education?

TED ROSENBAUM “I was called down to McCarthy’s special hearing room at Foley Square in Manhattan, where he and Roy Cohn, his henchman, conducted an inquisition. You can imagine how horrifying this was. I got myself a lawyer, who advised me, ‘The best, smartest thing you can do is keep your mouth shut. If you answer one of his questions, you’ll have to answer them all. Not that you have anything to hide. But he has no right to cross-question you.’”

Before McCarthy could question him, Rosenbaum felt the need to give the senator a history lesson. He said, “The Fifth Amendment was written into the Bill of Rights by real patriots to protect innocent people from public officials. Taking the Fifth Amendment does not mean a person is guilty of any wrongdoing. It compels government officials to obey the principle that a person is innocent until proven guilty.” Rosenbaum said he had committed no illegal acts, either in or out of the classroom.

Senator Joseph McCarthy and his wife. Library of Congress

TED ROSENBAUM “Sure enough, he asked me, ‘Are you a member of the Communist Party?’ I gritted my teeth. Oh boy, was I fuming. I said, ‘You called me down here because presumably I did something wrong. What did I do wrong?’

“He cited me for contempt. We went up and back, and when it came to it, I refused to answer. Before I left the session, I had sixteen citations for contempt, and it killed me, because I would have liked to have told him off. But my lawyer looked at me, warning me to keep quiet, and when I walked out of that room I figured I’d be going to jail for the next ten years. I came home, and my wife and I were petrified.”

When it became known that Rosenbaum and Gilgoff were being investigated and might be fired as teachers, a petition to retain them was signed by Justice Delaney; Lindsay White, past chairman of the NAACP; Rabbi Louis Gross, the editor of the Jewish Examiner, and more than fifty ministers, rabbis, and other community leaders—both white and black. Said the petition, “Their threatened dismissal would be a victory for McCarthyism in our schools, and a threat to our democratic institutions.”

Wrote Justice Delaney, “The public should become aroused and concerned about the sincerity of purpose of a Board of Education which goes easy on a May Quinn, who admittedly spreads anti-Negro and anti-Semitic poison in her classroom, which on the other hand, it tries to pin the red label on teachers who fight to keep alive in their community the spirit of the Bill of Rights.”

An editorial on November 23, 1951, in the Jewish Examiner said, “Instead of injecting the red issue into a clear and shocking case of injustice, the Board of Education should have publicly commended the two teachers for their social conscience and courageous initiative in coming to the aid of a Negro family.”

The pleas fell on deaf ears.

On April 30, 1954, Rosenbaum was fired from his teaching job and blacklisted.

TED ROSENBAUM “I was dismissed by the New York City Board of Education because I had refused to answer questions posed by a federal authority. And I was kept from teaching for eighteen years! In those days, the atmosphere, I can’t tell you, was so horrible. I couldn’t get a job anywhere, and I was Phi Beta Kappa and I had a wonderful record as a teacher.

“A friend of mine, Herbert Kurz, head of the Presidential Insurance Company, offered me a job. He said, ‘How about working for me? You’ll make a wonderful insurance agent.’

“‘Who the hell wants to be an insurance agent?’ I said. But in desperation I succumbed to him, and I filed an application with the state superintendent to sell insurance with Herb’s recommendation attached. A week later he got a call from the state superintendent.

“‘Do you know this guy?’

“‘Yes, I do.’

“‘Tell him he has no chance. I am sending out my response today.’

“That was the atmosphere in those days. So I didn’t get the job. It wasn’t until 1972, when an outfit called the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a public employee may not be lawfully dismissed under section 903 of the New York City charter under circumstances that infringe upon his constitutional privilege against self-incrimination. At the end of that year the New York City Board of Education amended its by-laws to reinstate all employees like me, who had been dismissed under section 903, and in December of 1972 I was reinstated, and in 1976 I was granted the annual retirement allowance from the New York State teachers’ retirement system, based on my twelve years of service. That included health benefits, which I am receiving to this day.

“Unable to get work, I decided to change my name. Terry was an unusual name, and so I changed it to Theodore, which is my name today. Ted Rosenbaum. And I pursued another career, that of a fund-raiser. I was hired by the Educational Alliance on the Lower East Side, the second-largest settlement house in America next to Hull House in Chicago. It was formed at the end of the nineteenth century, and it provided housing to immigrants, to some of the greatest names in Jewish history, entertainers like Eddie Cantor, George Jessel, and Sam Grosz.

“When I started, my goal was to raise a couple million dollars, to double the size of the facility. You don’t raise that much money by knocking on doors and getting nickels and dimes. No, you have to go for the big bucks.

“I began researching the board of trustees of the Alliance, whom they knew, when one of the guards outside came over and said, ‘Mr. Rosenbaum, I got to tell you a story you might find helpful. For years a big limousine would pull up, and out of it came a man, a very dignified man, evidently very well-to-do, and he’d come in, walk to the lobby, and then walk into the auditorium, where he’d sit down for a couple of hours without saying a word. And then he’d leave. Year after year.’

“You didn’t have to be much of a brain to figure out who the man was. First, he had a big limousine and he had money. Second of all, he must have been emotionally involved to come back year after year. I figured, I’d better find out who knows him and get an interview with him. The mystery man, it turned out, was David Sarnoff, the founder of RCA.

“I went to see him, and I told him who I was and what I was doing. I said, ‘Tell me. What made you come up year after year and sit in the back of the auditorium?’

“Tears came to his eyes. He said, ‘My father was an immigrant.’ (He was this powerhouse, and I can see him crying now.) He said, ‘I sold newspapers outside the Alliance to earn a few pennies for my family, and one day they called me in and said, ‘Would you like to be in a play we’re putting on?’ Sarnoff said, ‘I was scared stiff, but I couldn’t say no. I was afraid they wouldn’t let me stand outside selling newspapers. So I joined the play. I had one line: “Cleanliness is next to Godliness.”’ And he said, ‘I was on the stage with the other kids, and I forgot my line!’

“I told him of our plans, to extend the Alliance facility to make it possible for hundreds of new immigrants to stay. And he gave half a million bucks to start with, and he got friends of his to kick in several million bucks more. And that was how I started my career in fund-raising.”

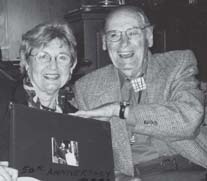

Ted (nee Terry) and Beth Rosenbaum celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary in 2001. Courtesy of Ted Rosenbaum

Rosenbaum’s next job was working for the Long Island Jewish Hillside Medical Center. They had heard about Rosenbaum’s success, and they wanted him to head the effort to build the first regional children’s hospital, covering forty-three communities in Queens and Long Island. Each local hospital treated children, but none had the expertise or the equipment to treat the most seriously ill cases.

TED ROSENBAUM “I don’t have to tell you, knowing my background, how excited I was to be part of building a children’s regional hospital. I took the job, and I worked there eighteen years, and in 1983 it was opened and dedicated by Governor Mario Cuomo.”

In 1990 Rosenbaum moved to Leisure World, the largest retirement community in the state of California. He is one of eighteen thousand residents. When he arrived, other members of the community began talking about setting up an organization for universal health care. It was an issue right up his alley, as he describes it.

TED ROSENBAUM “I became their political consultant, and then their president, and for the last seventeen years I’ve been working on that project. There is now a bill in the state legislature called the Senator Kuehl bill SB-840, which passed the Senate and is now being processed through the California assembly. It has to go through a couple more committees, but at this point, with the political mess taking place, I doubt that Governor Schwarzenegger will sign it, because of the tax implications. And we’ll need a two-thirds vote to override his veto.

“We have 6 million uninsured people in California alone, and over 15 million underinsured. This issue turns me on, even at age ninety-plus. I’m up to my goddamned ears.”