ITALY WAS A TERRIBLE PLACE TO LIVE DURING MOST OF THE eighteenth century. Only a third of the land was cultivated. People were poor. Food was scarce. Few homes were heated. The country was run by the autocratic Hapsburgs, a ruling elite that owned most of Italy’s wealth, and they paid very low wages. Moreover, little money was spent on education for the masses, and most people were illiterate. Upward mobility was rare. And no one could leave, because the Hapsburgs made emigration illegal.

In 1871, when Italy’s reunification was more or less complete and the various states had formed themselves into a nation, the ruling class imposed a brutal tax on the workers. Italians started to leave, but most went to other European countries, and many of those returned. Many of the emigrants who left toward the end of the nineteenth century went to South America, mostly to Brazil and Argentina.

The flood of Italians to the United States began in 1891 and continued until immigration was halted by the Congress in 1917. Four million Italians came to America between 1890 and 1920. Family members would come over, then write home letters glowing with promises of low taxes, plenty of work, and freedom. Some towns in Calabria and the Basilicata lost as much as 20 percent of their population.

La familia—the family—provided Italians with protection, assistance, and friendship. Italians defined themselves by the part of Italy they came from. They came as Venetians, Calabrians, Neapolitans, and Sicilians. They settled where their former neighbors lived. Italian immigrants did not feel isolated, rarely became public charges, and rarely suffered from alcoholism or from mental illness.

Another reason they banded together was that they were Catholic, and the American Puritans were hostile to them because of their darker skin and their religion. The Protestants didn’t want them living next door.

Library of Congress

The wealthier northern Italians tended to move west, as far as California, where they raised grapes and made wine. The poorer southern Italians stayed in New York and other eastern cities, replacing the Irish on work gangs, building subways, skyscrapers, and fixing streets. Italian women joined the garment industry.

Life for the new Italian immigrants was hard. They worked long hours for little pay. They were targets of both the police and the mafiosi who preyed on them.

Though the Italians and the Irish had the Catholic Church in common, the Irish were prejudiced against the Italians because they weren’t orthodox enough. The Irish were contemptuous of the Italians’ love of processions during which they carried around tall statues of their favorite saints. For their part, the Italians felt the Irish too puritanical and cold. The Italians also were contemptuous of the Irish always hitting up their parishioners for money.

The worst of anti-Italian feeling came in 1920, during the Sacco and Vanzetti trial. Sixteen witnesses swore the two men were miles from where the murder in question took place, but they were convicted anyway. The jury foremen called them “dagos.” There were whispers that they were anarchists. In the midst of A. Mitchell Palmer’s Red Scare, they were given the death penalty. Like the Salem witch trials, it was a travesty.

In 1917, the Congress passed legislation demanding that immigrants be literate. A yearly quota was established at six thousand, and it remained that way until 1965.

Because most immigrants from southern Italy came from a farming background, they were suspicious of the public schools. Moreover, first-generation Italians wanted their children to go to work for the good of the family. They had a saying, “Don’t make your children better than we were.” As late as 1960, only 6 percent of students at City College had Italian names.

The second generation was tired of hearing how life was in the old country. They sent their kids to school, adopted a different manner of dress, became more American.

Curtis Sliwa, the founder of the Guardian Angels, was the son of a strict merchant seaman of Polish ancestry and a doting mother of Italian descent. As a child, he grew up in Canarsie in the home of his maternal grandparents. In the Italian culture, the youngest child took care of the parents in their old age, and so, in 1959, when Curtis was five, the Sliwas moved in with the rest of the Bianchino clan so his mom could watch over them. With his father away most of the year, young Curtis, the only male child, was the mamaluke in the family. He could do no wrong in the eyes of his kin. On the street he learned from the gavones who populated Canarsie and the Jewish kids with whom he went to school. Growing up in a Roman Catholic household, more than anything, he learned that selflessness and sacrifice would bring him closer to God.

CURTIS SLIWA “I was born in Brooklyn Hospital in downtown Brooklyn on March 26, 1954. It was Dr. Duckman who slapped my tuchas and caused me to start jawboning for the very first time, and I haven’t stopped since.

“I was eleven pounds, eight ounces, born to Frances Sliwa, a little Italian-American woman. I was heavy, and I had slanted eyes, so the medical staff assumed I couldn’t be her baby after they saw my father, Chester, with his blond hair and blue eyes, and my mother with her dark hair and dark eyes. They said, ‘Neither of you have Asian features. This can’t be your kid.’ It took twenty-four hours to straighten it out.

“Ironically, Dr. Duckman’s son became a judge who actually got defrocked and thrown off the bench in Kings County for caring more about a convict being able to take care of his dog—that’s why he released him and let him go home—than about the woman he was stalking who he wanted to kill. So guess what he did? When he got let out of jail, he went and killed the girlfriend. A tremendous bloodline there.

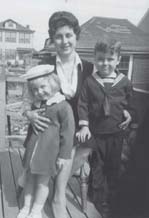

Curtis Sliwa as a young boy with his mother and sister. Courtesy of Curtis Sliwa

“My dad, the oldest of four boys, was born on the South Side of Chicago. My grandfather Anton and my grandmother Wanda were both born and raised in Poland. They met in Chicago, which had a huge Polish enclave.

“My mother was the thirteenth and last child in her family, and the only one born in America. Her parents, Fidele and Nicoletta Bianchino, were from Bari, Italy. Fedele could not read or write, but my grandmother was very learned, very educated. They were an odd couple.

“They came here after World War I. Fedele served in the Italian army in the Alps. He had volunteered as an English interpreter, even though he didn’t speak a word of English. Anything to avoid being hung or shot by the Austrians or the Hungarians. His attitude was, ‘You need an English interpreter? I want to learn English. I want to go to America.’ He couldn’t read or write. He survived the war, and he was living in poverty. He said, ‘Let me go to America. I’ll see if the streets are really paved in gold.’

“He came to Brooklyn and went back, and he said, ‘It’s a hell of a lot better than living in a mud hut with twelve kids and a horse.’ And the horse had the most room. As my grandfather said to his kids about the horse, ‘He makes money. You cost me money.’

“He arranged for the whole family to come to America. His cousin Lemesta, who owned a funeral parlor, was going to vouch for him. But Fidele told him he only had four kids. So when Lemesta arrived at Ellis Island, he was taken by surprise when he saw Fidele, Nicoletta, and he counts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve kids, and he sees that she’s pregnant with my mother.

“Lemesta said to the customs official, ‘I never saw that man before in my life.’ Remember, if you sponsored someone, you had to be responsible for him. If they couldn’t make it on their own, there was no welfare, no social services. You had to pay their bills. So Lemesta freaked.

“My grandfather went nuts, and they quarantined him on Ellis Island. He eventually was able to contact another cousin who took them in. If not, the whole family would have been shipped back. My uncle Leonard had a mastoid ear infection. Eventually he would die of it, but they wouldn’t let him in. My aunt Mary had a cough, and she was terrified they would think it was whooping cough. She had heard the horror stories about not passing the physical. Even if you had lice, that was it. Back you went.

“My grandparents had a tough survival, but they always reveled in how many failures they had had to endure before the ultimate success—from getting their first apartment, a cold-water flat on Skillman Street and Myrtle Avenue in the heart of Fort Greene.

“Fedele had told the landlady, ‘We have just five kids.’ Because five was the limit.

“‘If I see any more kids, Mr. Bianchino, out you go.’ So every day he would have the younger kids wait in the school yard of the public school on Kent Avenue until it was very dark and then he would wagon-train them into the apartment. Good weather, bad weather, they would have to wait until the landlady went to sleep.

“One night she must have had agita, no Brioschi, and there she was, eagle-eyed, and she started counting, ‘Seven, eight, nine, ten…’ After Grandpa got them all into the apartment, she knocked on the door. She came in and said, ‘Esci fuori da questa casa.’ Which means, ‘Get out of this house.’ And that was it. There were no social services, no shelters. They took what little they had, and out in the street they went.

“Nowadays, you tell a story like that, and you lie on a couch watching Oprah, and she explains why you’re dysfunctional, why you can’t seem to have a relationship, why you became a dope fiend, and there’s my grandparents and my uncles and aunts telling their story, busting their buttons and britches with pride, saying, ‘Yeah, it was cold. We had nowhere to go, but we all pulled together, and we walked for hours until eventually we found a place to stay.’

“They walked all the way out toward Canarsie, which is a long haul. Canarsie was God’s country back then, because the farther you went east, you would start hitting undeveloped areas, fields and lots, old farms still, and to my grandfather, this was nirvana. He felt like Lewis and Clark of Brooklyn. He said, ‘I’m going to save my money, and I’m gonna buy a house in Canarsie.’ People would look at him and say, ‘Canarsie?’

“Canarsie was known for three things: the dump; a mini–Coney Island called the Golden Gate, right by Jamaica Bay; and a red-light district. Back near Paerdegat Bay were the houses of ill repute built on poles stuck in the water, the shanty shacks, and people like Mae West and others would perform in the jazz clubs, because jazz was considered the evil music, the cultural debaucher of the time. You’d drink at the gin mill and try to saddle up with a lady, and then go from the hooch mill to the brothel. That was what would attract people to Canarsie. It was out of the way, out of sight, out of mind. But the rest of Canarsie was like the Little House on the Prairie, undeveloped land, and eventually my grandfather saved his nickels, dimes, and pennies working a variety of manual-labor jobs, and he bought his house on Remsen Avenue.

“Back then a traditional Italian household would always be occupied by the extended family. Aunts, cousins, nieces, nephews—this was a huge family in the Bianchino compound, where my grandfather would work in the dirt-rock garden. No grass. No concrete. Italians were known for that. Just dirt, rocks, tomato plants, fig trees, parsley, and basilico [basil], and that was heaven, a slice of the old country.

“The extended family would contribute to the family’s welfare. My grandmother Nicolette was a seamstress. She would do piecework at home while she raised the kids.

“My grandfather would wake up in the wee hours of the morning and go to work as a manual laborer, a pick-and-shoveler, to dig. He said, ‘We were the bottom of the ethnic food chain, guineas, wops, and dagos.’ And it was worse if, like him, you couldn’t read or write. If they needed an extra body, he was hired, but they would go through the other ethnics first. The Italians were like the Puerto Ricans later on. Most times he didn’t get picked, so he would have to walk all the way back. He would have to find a piece of cardboard to put in his shoe where the leather wore out. Because he didn’t have the nickel for the trolley. So he walked miles, just to shape up, to be told most times, ‘Go home.’

“My grandfather would be out from sundown to sundown, literally dark to dark, six days a week, shaping up. My mom would say, ‘I wonder who that man on Sundays is,’ because she was the youngest, and she’d usually be asleep when he came home. If he didn’t hustle, the family would have starved. As I said, there was no food stamp program, no welfare. He never held a regular job until he was in his eighties.

“When we moved in with him in 1959, he was eighty-one and I was five. They had started building subdivisions in Canarsie, and he was hired as a night watchman, a job he took super-seriously.

Curtis Sliwa’s maternal grandparents, Fedele and Nicoletta Bianchino.

Courtesy of Curtis Sliwa

“Back then there were many organized-crime families in Canarsie. That was their burial ground. The gavones, the shadrools, the muscleheads with muscles between both ears, the up-and-coming cugines, would earn their stripes by developing their track record of being able to steal and earn, and the way they would do that was by going to these work sites late at night and stealing materials.

“The job of the typical night watchman was to make sure they didn’t get greedy, to make sure their skim wasn’t excessive. Not my grandfather. He would say, ‘What do you mean, skim? What do you mean, vig? What do you mean, percentage? Not on my watch. I was hired to see that nobody steals. That means nobody steals.’

“My grandfather hated the Cosa Nostra, the Black Hand. Sometimes I would go with him on his route checking the different sites. He realized he couldn’t cover the entire enormous area of subdivisions, so he would set up booby traps. He used nails and broken glass. He dug holes the thieves would fall into. And he would catch them and turn them over to the cops, and this was considered disgracia. When he had information, he’d say, ‘Juan yowan,’ meaning ‘Come with me.’ And he’d go to the 69th Precinct and demand to speak to a detective. This was not the police department of Rudy Giuliani. This was a police department that had been corrupted, that had links to organized crime, and the cops would turn around and tell the old-timers, who I call the Geriatric Psychotic Espresso Killers of Organized Crime, with the pinkie rings, that this crazy old man was ratting out their nephews as they were trying to earn their stripes. So they would approach him, sometimes in my company.

“‘Hey Pops, who do you think you are, the FBI—Forever Busting Italians?’

“‘Old man, you know the custom from the old country. You be swimming with the fishes in Jamaica Bay. You gotta big mouth.’

“‘This is my job,’ he would say. ‘If the boss doesn’t like the way I do my job, he’s gonna fire me. I’m paid to make sure nobody steals, and that means you, your cousins, your nieces, your nephews, my sons, my daughters. Nobody steals.’

“He wouldn’t bend, would not fold like a cheap camera. He stood resolute.

“They acted like they were going to whack him, but they didn’t, because he was eighty-one. They treated him like you would your crazy uncle on gatherings, Thanksgiving, or Christmas. They would say, ‘The old man is oobatz, he’s meshuggener, he’s tetched.’ To punish him, they exiled him from the boccie court, where all the old-timers would come together and network, talk, exchange stories from the old country. Because he was such an in-your-face anti–organized crime guy, they wouldn’t associate with him, wouldn’t let him around them. He basically had to exist as a loner.

“There was him and me, and when he began developing cataracts and hardening of the arteries, I got him a big dog, part German shepherd, part Great Dane, to protect him. The name of the dog was Butkus. After the football player Dick Butkus, because he would tackle people. If you got too near the old man, Butkus would take you down. And Butkus was huge. In Italy my grandfather had had a hunting dog called German, named after Germany, and he would go out with the dog and shoot pigeons for the family meal. Pigeon soup was considered a delicacy in Italy. In America you’d say, ‘Are you out of your mind? Eating a flying rat?’ But in Italy it was considered a delicacy. He’d go hunting all day with German and come back with one or two pigeons.

Chester Sliwa. Courtesy of Curtis Sliwa

Frances Sliwa. Courtesy of Curtis Sliwa

“My grandfather was starting to have his senior moments, and so he would think Butkus was German, and he’d think he was going out hunting on the streets of Canarsie. He would see the pigeons, and he’d aim his phantom rifle. Butkus would look at him like, This guy really is oobatz.

“My mom, who lived at home with my grandparents, went to Tilden High School, the same high school that produced Al ‘Slim Shady’ Sharpton years later, and a host of others, including Willie Randolph, who was the manager of the Mets. It was a very good school, and she did fairly well and went into clerical work. She started working in an office in Manhattan before World War II, and she met my dad, a merchant seaman.

“My dad went to Lane Tech in Chicago, but he was the oldest son, and because of the Depression he had to go to work. He sailed flatboats down the Mississippi. Once at the port of New Orleans, he was able to sail on banana barges to Central America in order to make more money to send home, and eventually he worked on cargo ships, which prepared him for World War II. He went to Officers’ Candidate School with the merchant marine. They sent him to a training facility where Kingsborough Community College is now. He would have to row out into the middle of Jamaica Bay in the winter, and they would throw him over, and he’d have to survive. This was in preparation for the Liberty fleet, where they knew ships would go down in the North Sea in the Atlantic, and you’d perish in a matter of minutes because of exposure, so they were trying to prepare them.

“My dad was an excellent swimmer. The idea was to stay afloat, swim, avoid the riptide, avoid the currents. He was assigned to a ship berthed out of Brooklyn, and networking in Manhattan he met my mom. They got married in St. Patrick’s Cathedral right before the war, and when the war started, he got shipped out.

“He was a second mate, and he’d be on watch at night with all the lights out, knowing that as soon as they left the Port of Brooklyn and went through the straights of Verrazano out past Coney Island, the German wolfpack would be waiting. They would start with a convoy of sixty-five ships, and the subs would start picking them off one by one, and by the time they arrived in England, they’d be lucky if thirty-eight made it. It was night, and there was nothing you could do. His boat was never hit, but he had a lot of close calls. Toward the end of the war, after Germany had given in, he went to the Pacific until Japan surrendered, and he continued to sail right through the Korean War.

“When I was a boy, my dad was away eight months of the year, sometimes ten. Back then if you went into a port, it took days to unload and load. He would go from port to port in the Middle East and then to Asia and then to California and through the Panama Canal and down to Argentina.

“My dad being away affected me in only the most positive way. Others would say, ‘My dad was away. I didn’t have a male role model.’ I was the only boy in an Italian household, and I became a mamaluke. To your mom and your aunts you could do no wrong. The girls would grow up like they were living in a convent. They had a curfew. If guys looked at them the wrong way, your cousin would hit them so hard their mothers would feel the vibration. They were under constant observation. Guys? We had the freedom to do whatever we wanted. And I was never wrong in the eyes of my grandmother, my mom, or my aunts. Like I said, I was a mamaluke, the king, the prince, the jambeen. My dad wasn’t of the Italian culture. He was more brusque. Along with four brothers, he had grown up with all men in his family, other than his mother, so it was a totally different energy. It was great to have him home a few months of the year, because he was great at telling stories and painting pictures of all these unbelievable ports of call. He would say, ‘You could see the powerful Nile sweeping down and seeing all the crops growing and the Egyptians in their ancient boats, and yet a modern city, Cairo, but you also had to watch out for Ali Baba and the forty thieves, ’cause merchant seamen were considered easy prey.’

“He would say, ‘A merchant seaman was the most despised pariah. It was thought, Lock up your women. They’re drunks, thieves, crooks; they have syphilis, and scurvy—but, he told me, ‘We were the most avid readers, because that’s all we could do on our off time.’ There was no radio or TV on the ship. They read books. So he would bring home with him a treasure trove of 25¢ classic books. They were the most learned. They would write great prose, but the minute they hit shore, the cops were out looking to bust them. Everyone was fearful of the seamen, though they were just hardworking guys who came from all over to sail. He would also explain the different ethnic groups, because we lived in a melting pot, New York City.

“I grew up around a lot of mobsters in Canarsie. My grandfather, who wouldn’t be bullied by them, would say, ‘Look at these men. They sit on the steps all day. They eyeball the working man, the man who goes back and forth to work, who opens and closes his store. They scheme all day, thinking, ‘How am I going to take that guy’s money without ever having to work a day in my life?’

“My grandfather said to me, ‘You shake their hands, and their hands are soft. ’Cause even though they act tough, they never worked a hard day in their life.’ So I would be walking through the neighborhood, and you would see exactly what my grandfather described. And worse. These older men would take under their wing young, impressionable teenagers, many of whom I played ball with, associated with, and I could see them eating up their minds with negative propaganda. They could dazzle the young people with their talk about chasing skirts, hanging out, carousing.

“They would say to the kids, ‘What are you going to get from a book? You a freakin’ moron? You gonna collect ten trillion Green Stamps so you can buy a toaster? You can own the store that sells the toasters. You’re just not out front. You’re protecting the man’s business.’

“And I would say to the kids, ‘Who are we protecting it from? We are protecting them from us. We’re protecting the guy’s store from us, so we don’t burn it down or don’t break his window. What are you, some kind of moron?’

“And the answer would come back, ‘If we don’t do it, the guys on the other block will.’

“That’s how it would start. They might say, ‘You look like a bright kid. Didn’t you ever want to go joyriding in a car?’ The kid would say, ‘We’ve done that.’ The old man would say, ‘Why just joyride? The car is valuable. For parts.’ They start talking economics, supply and demand. ‘If there’s a demand, say for a Lincoln Town Car, you joyride the car, you bring it to the chop shop, and you get money. It’s not that hard to do. You’ve already taken the car. Bring it in and you make some moola.’

“When they started out, my friends like Joseph Testa, Anthony Senter, they were pretty boys, real Italian stallions, lover boys. Over time the Old-Timers would work on them, and they would change. One vicious predator, Roy DeMeo, was a total psychotic killer. He didn’t live in Canarsie, but he would come to Canarsie at the Amoco Station across from South Shore High School, and he would hang out, and he’d get these kids to come there, and they’d start stealing cars, get money for parts, and he’d be infecting their minds. Before long, he had a crew of created psychotic killers. There were no doubts in my mind Roy DeMeo’s furniture upstairs was arranged in the wrong rooms.

“As they were reaching their late teens, early twenties, I couldn’t even recognize them. For instance, when Joseph Testa was a little kid, we were playing with a slingshot. We would go to the open fields, the lots where some people dumped debris, and we would shoot at blackbirds and rats. Naturally we couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn. But this time Testa pulled the slingshot back with a rock in it, and he hit a sparrow in a tree, and the bird fell down, and it was flapping around, and the kid started crying like somebody had turned on a faucet. This was no hard-core, stone-cold killer. So how does that person ten years later become impervious to any human sentimentality? Was he born that way? No, but Roy DeMeo and the other Old-Timers kept feeding it. And Roy DeMeo and his crew went on to become the most vicious killing crew, hired out by John Gotti Sr. and others to do their dastardly deeds.

“Years later we found out what they were doing. They would meet at the Gemini Lounge on Troy Avenue in East Flatbush, just outside Canarsie, or they would meet at the Veterans & Friends Social Club, a main hangout in that same section of Brooklyn, and there were other gin mills where they’d hang out some. But in this den of doom and gloom, the Gemini Lounge, they would get the contract to kill guys, and they became so proficient, it became a slaughterhouse.

“They’d get contracts, lure their victims to the Gemini Lounge, and they’d have girls there, drink, have a good time, and then they would lure the victims into the back area, and they’d stab them. They perfected the art of draining the body of blood. They’d hang them upside down in the bathroom, drain the body of blood, chop up the body parts, package it for disposal in plastic sheets, and have a private carter pick up the plastic bags, and they’d be dumped in the Spring Creek dump along the Belt Parkway. Or the body would be put in a barrel, filled with concrete, and dumped in Jamaica Bay. Occasionally, they didn’t put enough concrete in, and the barrel would surface, and the NYPD would have another murder case. Guys suddenly would be missing in action, off the street, boom, gone.

“DeMeo used to be referred to as the Murder Machine. The Gambino guys were terrified of him, because he was a total psychotic. One day in the 1980s he was found in the back of his car, shot multiple times.

“There are guys I’m having trouble with today who come out of the Gotti wing of the Gambino crime family. I grew up with Little Nick Corozzo, who is now underboss and the titular head of the Gambino crime family. No one wants to be labeled the don, because they fall fast and furious under indictment. So Little Nick is the titular head, and his brother JoJo is the consigliere. And JoJo’s son Joseph is a criminal defense attorney who has represented his father. That’s intimidating, because you are not going to want to be cooperating with the government when Joseph Corozzo is the lawyer.

“Little Nick’s father was Big Nick Corozzo. Little Nick-Nick and I used to play stickball together when we were about eight years old. This one day I was batting, and there must have been a tornado behind me, because I hit the Spaldeen with the sawed-off stick from my grandmother’s broom, and it had to have gone two and a half sewers, which was like a miracle. There was a strong gust of wind, and I lifted the ball, and it hit the windshield of this all-red Cadillac Eldorado with the top down and the little dice in the front and the Italian horns, the cornu with the crown on it.

“This well-dressed guy was sitting on the stoop talking with this Old-Timer, who may have been sixty. The Old-Timer was smoking the Italian stinker. The ball bounced off the car, and the guy in the suit, who was in his twenties, grabbed the ball, walked up to us, and he had an ominous look. He stared at us, and we were frostbitten from the tips of our noses to the tips of our toes.

“‘Whose fucking ball is this?’ he asks. Our reaction was ‘Ubabubbabubbabubba.’ We were barely able to speak. He pulled out a switchblade knife, sliced the ball in front of us as if he were slicing an apple, and he said, ‘The next person who hits a ball anywhere near my car I will gut out like a pig.’ And he used the term schifosa, which is a word you would never say in public. It’s a nasty, nasty word.

“We were terrified. We went all the way down the block so we would have had to hit the ball five sewers to hit that red Eldorado. I was seven or eight. We were shaking. And Nick Corozzo grew up to be an out-of-control, psychotic killer.

“This was the 1960s, early 1970s, and the city itself was beginning to change. The Old-Timers were getting kids into the traditional rackets, like stealing cars, but now the Old-Timers are having them trafficking in drugs: speed, cocaine. They’d get hyped up, really on edge. They were taking bathtub crank, methamphetamines, cocaine powder. Those drugs gave them a feeling of invincibility. They thought they could take on the world. But they also had drugs like Quaaludes and downers to lure the young ladies and break down their inhibitions. Man, if you had those, these girls couldn’t get enough of them. That was like candy to them. So one minute they might be playing stickball with me, playing street games, and they were also getting to be a little bit of wise guys, getting into a little bit of trouble. They were getting JD cards—juvenile delinquent cards—from the coppers, and don’t forget, at the time almost all the cops were Irish. We called them O’Hares or O’Haras.

“Meantime, most of the troublemakers were Italian kids. Jewish kids in that neighborhood were studying Torah, were in the library, were doing extra-credit reports. Occasionally one of them would become psychotic and want to be a wise guy, and since the Italians and the Jews got along, they’d adopt him. They’d say, ‘You’re going to be our accountant when you get older. You being a Jew, who knows? You may be on the parole board when we’re looking at twenty-five years to life.’

“But that kid was the rarity.

“Most people would say that life becomes better for them as they mature, get older, acquire wealth, equity, and are able to make decisions. I would go back in an instant, without hesitation, to the ages of six to twelve. I wish every kid could have had an opportunity to grow up in a place like Canarsie, Brooklyn. The neighborhood was, for me, nirvana.

“First of all, if you were Roman Catholic, you identified by what parish you belonged to. There were three in Canarsie; Our Lady of Miracles was mine. It was called OLM, and if you were a hard-core Roman Catholic you went to OLM or to Holy Family. These were the traditional parishes, called old-school parishes. OLM still had the Latin Mass, and when they shook the incense during the service, they’d shake the thing so thick you’d have to wear a gas mask not to pass out. We’re talking hard-to-the-core Roman Catholic service. Whereas the New Jack parish, St. Jude’s, which had just opened up and had no credibility, was artsy-fartsy, practicing with the Peter, Paul, and Mary folk Mass. And it was in English, not Latin.

“The other thing you identified your neighborhood by was the candy store/luncheonette. My cousin Lenny ‘Beans’ Bianchino’s dad, Uncle Ralph, owned the local luncheonette, and we would visit his mother, Aunt Sylvia, there. She was behind the counter, and she would smoke unfiltered Chesterfields nonstop like a chimney, and she had a raspy voice. We used to call her the Chesterfield Queen.

“One day she was bending over, using elbow grease to Ajax the counter, getting it to shine, when I saw the Star of David, what I called the Ben Hur symbol, drop out of her blouse. I thought, Oh, my God. I said, ‘Lenny, your mother. What’s with the Ben Hur symbol?’

“‘My mother is Jewish,’ Lenny said. I couldn’t believe it. We thought we’d be excommunicated if there was a Jew in our family. Her maiden name was Rosen. She was from Brownsville. At that time a Catholic was not supposed to marry a Jew, or vice versa, so it had to be very rough. Lenny wasn’t raised very religiously, either Catholic or Jew, but I couldn’t help but think, Lenny is going to be excommunicated. The Flying Nun is going to come down, and that’s it, buddy. No chance for you. Straight to hell without an asbestos suit. You can imagine the shock for me!

“But being in the luncheonette became the identity for your slice of the neighborhood. The guy behind the counter was usually a World War II vet, a guy named Sam or Louie. You would see his World War II picture behind him. He was a corporal at Guadalcanal, and he had a Japanese flag as a souvenir. He’d say, ‘Those nips. Those krauts. We taught them.’ In those days I couldn’t wait to read the comic Sgt. Fury and the Howling Commandos. It was so politically incorrect. They would never allow a comic like that nowadays.

“The person behind the counter took pride in how he made the egg cream. It was a science. The first thing you learned as a little kid was, ‘There is no egg in egg cream.’ I wanted to know, ‘Why do they call it an egg cream?’

“‘You ask too many questions. Just drink it.’

“The secret of the egg cream is the chocolate syrup, the glass being chilled appropriately, a chilled spoon, a long spoon, and the seltzer being spritzed in at the right level, and then naturally the wrist action where you’re beating the chocolate syrup and the seltzer to get that fizz.

“People prided themselves on how they made their egg cream. They were so proud that it wouldn’t foam over. They always had the proper texture, and naturally you had to have a salted pretzel rod—always so fresh—that came in one of those little canisters.

“The other thing we tried to do was bamboozle some pure Coca-Cola syrup, because we didn’t know it, but this was a drug: a little cocaine action. It was so good. You didn’t become addicted, but it was so sweet, so good, that you had to come up with a reason—a ruse—to get some. ‘My mom says I’m coming down with strep throat.’ Or ‘I have a stomachache.’ He was a combination soda jerk/pharmacist. If you were sick, your mom would send you down for it. ‘I have strep throat.’

“‘You have a lot of strep throats.’

“‘Yeah, and the doctor said they have to take my tonsils out.’ And he would buy it! Oh, it was so good. They only gave you a little bit.

“As for going to the movies, we went to the Canarsie Theater on Avenue L. The theaters were magnificent, with organ pipes and fine carpet and gargoyles. The Canarsie Theater wasn’t the most magnificent in Brooklyn—no way, those were along Flatbush Avenue—but for a local theater, everyone knew it. [It was gutted and turned into a banquet hall in 2004.]

“The big day was Saturday, matinee day. You went early, about ten o’clock, and you didn’t get out until two or three. You got to watch a few cartoons, and they would show a picture, and then they’d have a raffle—you could win a Big Chief Schwinn bike, dolls, a pancake mitt. I never won—and then they’d show another picture. The first flick was always better than the second flick. Before they invented day care, the movies on Saturday was it. The cost was a nickel, cheap.

Chester Sliwa in his sailor suit. Courtesy of Curtis Sliwa

“I was trained by Lenny ‘Beans’ Bianchino. I was the young guy, the shrimp. I had to earn my stripes. Every time I was there, about halfway through the movie, he’d say, ‘Curtis, there are ten of our friends outside. When I tap you on the shoulder, you’re going to act like you’re going back to buy some Jujubes or some Good and Plenty, and you look for the exit sign, and you break through, open the door, let the other guys in, and keep running.’

“Lenny’s friends were waiting, and once I let them in, they would run in all different directions, because the blue-haired matron with the white gloves and the K-Light flashlight knew someone was bum-rushing the door once she saw the light pierce the darkness.

“The matron was like a track star. They hid, but she had radar with night vision built in. If she caught someone she knew hadn’t paid, she’d grab him by the nape of the neck and the next thing you’d see, she’d be kicking them outside.

“Lenny’s friends would hide in the men’s room, because a woman walking into the men’s room was not good. She’d have to come in real quick and leave, so if you could stand on the porcelain palace, she’d look under the door and leave, and when they started the next show, you could run out and watch the movie.

“Sometimes we would go to Coney Island, but I preferred Rockaway Playland. We had a ’54 Ford station wagon with wood-paneled sides and white-wall tires. My dad came out of the Midwest, and he believed in Fords. The Italian side of the family said, ‘Ford? Ugh. The worst.’ They wanted GM. But Ford was a fixture in our house, and Mom would load us into the car, my older sister Alita, my younger sister Marie, and myself, and sometimes my friends, and she’d say, ‘We’re not going to Coney Island. It’s too crowded. You can never get on the rides you want, because you have to wait on the better ones, and the water is not the cleanest in the world. We’re going out to Rockaway Playland.’

“We were so excited. We’d take the Belt Parkway to Cross Bay Boulevard. On the way we’d stop at Aunt Mary’s in Howard Beach. We’d continue on Cross Bay Boulevard and pass Broad Channel, an island that separated the Rockaways from Howard Beach, and then you made a right, and you were at the Irish Riviera.

“You knew you were in Rockaway Beach because all the kids had freckles. No Italian kid had freckles. Maybe a mole. Never a freckle. But all the Irish kids had freckles, and every girl was named Colleen. They had blond hair, blue eyes. You would fall in love with the Colleens.

“Rockaway Playland had a roller coaster, had a Ferris wheel, had everything Coney Island had but was smaller and less crowded, and the beach was better. Rockaway Beach was on the Atlantic Ocean, not sheltered like Coney Island, so the waves were better.

“You couldn’t bring food onto the beach. The only ones who were permitted to sell food were the guys in the safari hats and the shorts selling Bungalow Bars, which was like a Klondike bar. It would melt in your mouth. They looked like they were on Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom.

“If you walked on the boardwalk, you’d better have a T-shirt on, or the O’Haras were going to cite you, and if you weren’t respectful, they would give you a wooden shampoo—hit you with their nightstick, billy club, blackjack, or truncheon. Oh yeah. ’Cause the Irish Riviera was their turf. You’re an Italian guy? Or you don’t look Irish? You don’t have freckles? Their attitude was, ‘You’re lucky you’re here.’

“We played all sorts of street games. The Italian kids competed in a game we called stretch. This was the ultimate test of total manhood. It was the predecessor of chickity-out, when you finally got a hot rod, and you’d race and come close to the other car, and the first one to veer away lost.

“In stretch you’d take a switchblade and throw it in the dirt. You put your foot right there, and the next guy would take the switchblade and throw it next to the foot as close as possible. The question is: Are you going to keep your foot there? How close does the knife come? It’s the ultimate test. And sometimes a guy would have to go to the emergency ward of Brookdale Hospital, because he wasn’t going to move his foot, and the other guy’s aim needed a little straightening out. Right into your foot!

“Some guys would just close their eyes. When they’d hear the click and the blade would go in the ground, they knew it hadn’t hit their foot, and they could open their eyes like they were tough guys. ‘You closed your eyes, punk. You’re supposed to stare.’ Oh, it was great.

“I was taught the game by my uncle Ralphie’s son, my cousin Lenny ‘Beans’ Bianchino, who was four foot eight, eighty pounds soaking wet. Lenny was so short he had a Napoleonic complex. He would challenge all the big guys, even though they were going to turn him into a speed bump.

“‘Don’t go up to that guy,’ I’d say to Lenny.

“‘No,’ he’d say. ‘Nobody treats me like that.’ And they’d pick him up and slam him down on his head. But he was tough. And Lenny loved baseball. We didn’t have Rawlings or Spalding gloves. We had the pancake mitt that was made in Formosa, aka Taiwan. You didn’t want to show it, because it didn’t have a brand name, and it didn’t have a signature, like Bobby Richardson of the Yankees or Rod Kanehl of the Mets. It only had that tag: Formosa. Everyone knew it was cheap, so you kept it tucked under your wing. The glove was bigger than Lenny was, but to make a good pocket, he’d take a hard ball, and then he’d take 22,000 rubber bands, and he’d tighten the ball up inside the glove so it made a pocket, and then he’d put the glove in the freezer.

“‘What are you doing, Lenny?’ I asked him.

“‘This makes a pocket,’ he said.

“We’d go to sleep at night after talking with my uncle Ralph, who was a degenerate gambler. At ten o’clock he would walk down to the local candy store and get the night-owl edition of the Daily News so he would have the racing form for the next day. It would also have the pari-mutuel results from that day, so you knew whose numbers won. So if you were playing the numbers, the bookie couldn’t rip you off, because you knew the right numbers from the night. At night there would be lines. Sometimes more people bought the night edition of the News than the paper in the morning.

“We’d go to sleep. The glove would be in the freezer overnight, and we’d wake up the next morning to go out to the fields and play hardball. He took the glove from the freezer, and it was like a rock, and he let it thaw out, and damn if it wasn’t a perfect pocket! It had such a perfect pocket the ball would just cuddle into it and not fall out. And he had oils. He put 10W-40 on it, and he’d work it, massage it. That glove was like an appendage, an extension of him. It became his personality, and he was very good with it.

“Lenny was three years older than I was, and it was he who taught me how to survive in the streets without being a sucker. He was in Little League, and I was there watching, and another kid came over and said to me, ‘Can I borrow your bicycle? I’m just going to ride it around the block. I’ll bring it right back.’ I was willing, but Lenny, who was in the on-deck circle, saw this, and he came running over with the bat, and he said to the kid, ‘I’ll knock your head off.’

“‘No, Lenny, I just wanted to take it for a ride.’

“‘You’re trying to steal that bike. That’s my cousin. If you steal his bike, I will come for you.’

“‘No problem, Lenny.’

“The guy was twice Lenny’s size, but Lenny just didn’t take shit from nobody. Lenny had this fearlessness he had developed. He was like my mentor, and I learned from him. I was able to accept what I felt was necessary and discard some of the other stuff that was over the top.”