LONG BEFORE THE JEWS LANDED IN AMERICA IN LARGE NUMBERS, the Protestant majority was threatened by the immigration of the Irish. Their feud went back to merry old England, where the Protestants worshipped God first, Oliver Cromwell second, and William of Orange third. Cromwell was loved because he drove out the “treasonous, idol-worshipping, priest-ridden” Catholics. When the Catholics staged a comeback in 1690, William of Orange defeated them at the Battle of the Boyne.

The Protestants banned the practice of Catholicism, so the Catholics had to worship in secret. The Protestants considered them to be spies of Satan, and felt it was God’s demand that they convert them to the freedoms and liberties of Protestantism by any means necessary.

In the 1700s the English passed what were known as the Penal Laws. No Catholic could hold public office. No Catholic could study science or go to a foreign university. No Catholic could buy or even lease land. No Catholic could take a land dispute to court. If a Catholic had been a landowner before the passage of the Penal Laws, he could not leave it to his oldest son. He had to divide it among his children, ensuring poverty within three generations.

Among the most draconian of the Penal Laws was the one that stated that no Catholic could own a horse worth more than 5 pounds. Any Protestant could look at a Catholic’s horse, say it was worth 6 pounds, or 60 pounds, or 600 pounds, and he could take it from him on the spot. The Catholic had no right to protest in court. Said Pete Hamill in his novel Forever, “In a country of great horses and fine horsemen, the intention was clear: to humiliate Catholic men and break their hearts.”

The enmity between the two groups was just as intense in America. There was a lot the Protestant Americans didn’t like about the Catholics: the Protestants saw the Catholics as clannish and intemperate. The Irish were in the habit of sending money back home, and so their loyalty was questioned. Worst of all, they practiced the Catholic religion, and Protestants were convinced Catholic monarchies and the Church in Rome were conspiring to undermine the American Revolution and the Protestant Reformation by sending immigrants to the United States.

Samuel F. B. Morse.

Library of Congress

How deep was the Protestant hatred of the Irish? Samuel F. B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, wrote a book, published in 1835, in which he said of the Irish:

“How is it possible that foreign turbulence imported by shiploads, that riot and ignorance in hundreds of thousands of human priest-controlled machines should suddenly be thrown into our society and not produce turbulence and excess? Can one throw mud into pure water and not disturb its clearness?”

The Irish insisted the initials F. B. in Morse’s name stood for “fucking bigot.”

More than a 100,000 illiterate Irish emigrated to the United States during the years 1843 and 1846, after the potato crop failed and it became a question of life or death. Most landed in Boston, because the fare was cheaper than it was to go to New York City, but large numbers of Irish immigrants nevertheless settled in the Five Points section of Lower Manhattan.

Protestants wondered whether Irish parents who refused to send their children to public schools could be good Americans. At the same time the Protestants gave the Irish good reason not to send their kids to the public schools. In the 1840s, textbooks would disparage them, and their children would be made to sing Protestant hymns and read from Protestant Bibles in public schools. Why should the Irish immigrants’ children have to be subjected to that?

There were anti-Catholic riots in Boston and Philadelphia in the 1830s and 1840s. Protestant mobs attacked Catholic churches. They attacked men they suspected of being Catholic in the street, with cudgels. In the 1850s the Protestants formed an anti-Catholic political party called the Know-Nothings. It was a secret Protestant fraternal organization—the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner—you had to be born a white Protestant to join and you took an oath to resist “the insidious policies of the Church of Rome and all other foreign influences.” When any question was asked about the organization, members were instructed to say, “I know nothing.”

In two years the organization had a million members. In 1856 the Know-Nothing Party, which had by then changed its name to the American Party, received nearly 900,000 votes out of 4 million, but its presidential candidate, Millard Fillmore, carried only the state of Maryland. Fillmore had been elected vice president on the Whig ticket with Zachary Taylor and assumed the presidency upon Taylor’s death in 1850. He did not receive the nomination of the Whigs in 1852. The party had largely faded away by 1860.

Anti-Catholic fervor returned during the Panic of 1893, a time of financial depression. Over time the Irish not only made up the bulk of New York City’s police and firefighters, but they banded together, organizing politically, and they took control of urban governments, whenever possible, to guarantee their rights. In New York they took over Tammany Hall, which controlled city politics until 1960.

Another significant Irish influx into Brooklyn came after the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883. This time they came in droves from Manhattan, as the Irish walked across the big bridge and settled in South Brooklyn, neighborhoods now called Park Slope and Windsor Terrace. Pete Hamill, the renowned journalist and author, grew up in Park Slope long before the area got its name.

PETE HAMILL “I was born in Brooklyn, in Bay Ridge, in 1935. When I was young, we moved to what is now called Park Slope by the real estate people. Nobody had fancy names back then. We called it ‘the neighborhood.’ We lived in three places. The first was right up near Prospect Park, a beautiful street with trees, and then we moved to a place right next to a factory, and that wasn’t so beautiful, and the third was a tenement on Seventh Avenue.

“My father came to America from Belfast, Ireland, in 1923. He was twenty. He was a young guy in Sinn Féin. The British and the Catholics in Ireland were in a war like the Sunnis and the Shia in Iraq. The British Protestants organized pogroms. Mobs would go into Catholic areas and burn houses, and the Catholic toughs, who were protecting what was their little privilege, fought back.

“The Protestants, for example, got all the decent jobs at the shipyards. The Titanic was built in Belfast, and one of the myths of Belfast was, ‘The Titanic hit the iceberg because they didn’t employ Catholics. God wanted to give them a good shot.’ So the deck was stacked against the Irish Catholics, particularly the men, especially if you piled up any sort of record of being in Sinn Féin.

“Michael Collins was the Irish leader, and when he was killed that year [1922], there was nobody left who was going to free them, and my father decided he better go. He had two older brothers who were already in America, so they were able to get him jobs. He came through Boston, which was the cheap ticket, and he came over with a guy by the name of Red Dorrian, who ended up running a very successful Manhattan bar, Dorrian’s Red Hand. They arrived in Brooklyn on July 4, 1923.

“He hated the British. I’d say to him, ‘You know, that Shakespeare was a pretty good writer.’ He said, ‘Yeah, but did you hear about the Sepoy Mutiny in India where the British shoved people into cannons and fired them?’ The British were like the Japanese. The farther they got away from home, the more savage they became.

“My father lost his leg playing soccer in the immigrant leagues in the twenties. He had played in Ireland, and when he got here, he played all over, from Brooklyn to the Bronx. There was an Irish team, a German team, a British team, and a Jewish team called the House of David. He got kicked, and they didn’t have penicillin, and gangrene set in. They sawed off his leg, so he did not go into the war.

“My father got a job in Brooklyn, and so he settled in Brooklyn. I’m sure he got the job through the Tammany organization. He was a clerk at one of the big grocery chains, Roulston’s, whose headquarters were down by the Gowanus Canal, so some of the logic of our moves was to live closer to Roulston’s. He had only gone through eighth grade, but he had good handwriting. He worked until the outbreak of the war, and then he went to work nights in a war plant in Bush Terminal. He worked on making bomb sights.

“My father went to Mass, but religion wasn’t a big deal to him. My mother was more religious because it gave her a certain kind of consolation. And she was better educated. Somehow she finished high school in Belfast. For a woman to do that was astonishing, because more of the girls went off at fifteen to work in the linen mills. And for a Catholic woman to get an education—it was hard to believe.

“My mother was born in 1910, and she had come to America before World War I. Her father had been an engineer with what they called the Great White Fleet, the British fleet that went to Central America and Panama. When she was born, her father decided it was time to live on land, and he didn’t want to live in Belfast, because of the religious strife. That was one of the reasons he and his brothers had gone to sea. Nobody at sea asked any of those questions. It was free.

“I was born in ’35, so the war started when I was six, and for kids my age comic books were the biggest thing. Captain America was always doing battle with a guy by the name of the Red Skull, who was a dirty, rotten, filthy, stinkin’ Nazi. He’d be sabotaging places, and I always worried he would sabotage Bush Terminal and my father. I was young and impressionable.

“And then after the war there was a lull where nobody could get work. All the war plants were closing. We thought our having to go to war was over. They didn’t realize this was just the beginning of the United States as a permanent warrior nation. Dad finally got a job in a factory across the street from where we lived at 378 Seventh Avenue between 11th and 12th Streets. Across the street on the corner of 12th Street and Seventh Avenue was the Ansonia Clock Factory Building, once the biggest factory in Brooklyn in the nineteenth century. Now it’s co-ops. My dad worked in a place called Globe Lighting in an assembly line, making fluorescent lights. So we had fluorescent lights in most of the rooms in our apartment. It turned everybody blue, the worst-looking thing you ever saw. To give you an idea how old these buildings were, we had old gas-lamp sconces on the walls from the time of gas lighting. They had been sealed up.

“The area that is now called South Slope is reasonably intact physically. A number of buildings burned down over the years, but there were no urban renewal projects. Basically the neighborhood was blue-collar. It was a good place to grow up. It was only a couple blocks from Prospect Park, and you could go to the park and walk across. You would see all the tribes of Brooklyn, the Jewish tribe, the Italian tribe, the Irish tribe, crossing the park to go to the ballgame at Ebbets Field. And after Jackie Robinson, finally, the black tribe. They finally got a seat at the table.

“One of the great benefits of my dad working at Globe Lighting was he got into the union, Local 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, Harry Van Arsdale president. So the family was obviously pro-union. The union gave people like that—as we will give the Mexicans, if they ever get legal—a chance to live a life with dignity. And of course they were Democrats.

“In the kitchen of our apartment at 378 Seventh Avenue, top floor right, were two pictures: the Sacred Heart of Jesus over the door and Franklin D. Roosevelt. I grew up with this vague impression that God must have liked Roosevelt—compared to the fucking dope we have who sounds like Tonto.

“The building had six apartments, and they were all working-class, either Irish or Italians. Right across the hall were the Caputos. Other Italian families were scattered about. It wasn’t exclusively Irish. The Jews were fading. There had been more Jews there, but after the war the Jews tended to take advantage of the GI Bill educational benefits, whereas the Irish, by and large, took the VA mortgages and moved to Long Island.

“It was not white flight. There were no blacks yet. The black migration didn’t start until the 1950s. There were a few Puerto Ricans around. A fighter by the name of LuLu Perez lived right up the block. He fought a famous fight against Willie Pep, which Willie dumped, the last time Willie fought in Madison Square Garden. The people in the neighborhood would yell at LuLu, ‘You couldn’t whip Willie Pep on the best day of your life.’ It was sad. LuLu Perez wasn’t in on the fix. He was a pretty good fighter. Everyone knew it was fixed, because Willie was such a bad actor. There’s a film of it, and you can see Willie shaking, trying to get an Academy Award in the second round.

“Within that neighborhood were different class levels. The closer you lived to the park, the better off you were. The people living in the brownstones were doing better than those living in the tenements. And there were brick houses around the corner from the tenements. Jimmy Breslin’s famous line: ‘He can’t be a crook. He lives in a house.’ And scattered in and out were buildings that were slummy.

“I went to Holy Name School. Holy Name was on Prospect Avenue, and Gil Hodges lived on that block while he was playing. I saw him a couple of times. The thing about growing up in Brooklyn, you didn’t ask people for autographs. You weren’t going to demean yourself. But you’d say, ‘Good morning,’ or ‘How are you?’

“I never asked my parents why they sent me to Catholic school, but I’m sure it was because the education level was higher. I ended up at a very good high school called Regis, a Jesuit school on 84th Street and Park Avenue in Manhattan. It took three trains to get there. At the time there were no Jesuit high schools in Brooklyn. There were two in Manhattan, Regis and Xavier, which was a semi-military school.

“The Jesuit schools are famous for creating atheists. I still stay in touch with some of the guys I went to high school with. They are all lawyers, and one of them is in the CIA. I once ran into him in Saigon, and then I realized what he was doing there. And it was a very good school for a young writer, an apprentice writer who didn’t even think he was going to be a writer at the time. We were taught Latin, and I took a year of German.

“I never graduated. I went there for two years, freshman and sophomore years, and then I went to work at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

“I quit for a number of reasons. One, there were money problems at home. Two, I found parts of school—Latin—really tedious. I had other ambitions. I could draw pretty well, and I wanted to be a comic-book artist. I was trying to get laid. How would I talk Latin to a girl from the neighborhood? All kinds of things were overlapping, but part of it was I wanted to get on with my life. And I had never met a single person who had gone to the university. It was common all over the neighborhood to drop out of high school and help support your family, until you had one of your own. And when I lived at home, I was the oldest of six. When I was seventeen, I went to work in the sheet metal shop at the navy yard.

“My mother was very upset by this, because it had been so hard for her to complete high school. ‘How can you do this?’ But my father didn’t care one way or the other. He only went through the eighth grade. I had already surpassed him. But the fact was, nobody ever went to the university.

“I had to take an exam to work in the navy yard. The Jesuits had taught me how to pass exams. I worked in Shop 17 as an apprentice. And the way it worked—a wonderful idea for working-class kids—you worked for four weeks and then you went to school for a week, so there was still more schooling, though most of it was for their purposes. I had to read blueprints, so there was some math. You didn’t get much exploration of Caesar’s Gallic Wars, but it was pretty good, and the great value to people like me was it taught me how to work, how to get up in the morning and get on the train and get there on time and do work I didn’t like, take it or leave it. I didn’t like it, but I didn’t hate it.

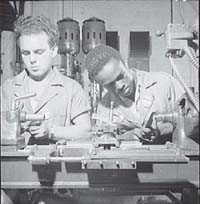

Blacks and whites worked side by side in the machine shop at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Library of Congress

“The basic work that was going on was the conversion of aircraft carriers to jets. Because there was so much vibration from the jet fighters, they had to redo the top couple of decks and that meant we had to take the flight decks apart. It was one of the best jobs I ever had. I worked with a black burner who used an acetylene torch to cut out the old bulkheads. You could never make a clean cut with one of those torches, so I would come along with a twenty-five-pound sledgehammer and smash the hammer down on the wall. I would step over that one and move onto the next one.

“The majority of the people at the navy yard were like the majority of the people in Brooklyn—Irish. I met people there who knew my father when he was playing soccer. But there were black faces all around the place.

“It was federal civil service, so it was integrated. There were black students in the apprentice program. Truman had integrated the armed services, and the navy was supposed to be integrated, but it really wasn’t. It was still segregated by jobs. If you were black, you would make a great cook, but you would not make an airplane mechanic.

“But before the integration of the armed services, before anybody, there was Jackie Robinson. We didn’t learn humanity from our first experience working with a black person in Brooklyn, because we had Robinson. And by then, we had Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe.

“I worked in the navy yard in 1951, and at night I went to the School of Visual Arts on 23rd Street and Second Avenue in Manhattan, which was originally called the Cartoonists and Illustrators School. I studied with a guy by the name of Burne Hogarth, who had been an artist on Tarzan. He was a wonderful teacher. I’d finish at the navy yard at four and then try to go home and change clothes, but if I couldn’t, I took the subway and went to 23rd Street, and there was a library across the street, and I could sit there and doze until class began at seven. I was making forty dollars a week, so I didn’t have much to spare, but it was great. I had a sense of what an art school was.

“I had a wonderful teacher by the name of Tom McMahon, who saw that I had some kind of talent and let me write whatever I wanted to write instead of ‘My Trip to Albany.’ That was a terrific thing—a piece of luck. He had read everything, and he pushed me in certain ways. I read Katherine Anne Porter’s short stories for the first time. I read Dos Passos.

“I worked at the navy yard for a year, when I realized I had fucked up stupidly by dropping out of high school. I thought if I went into the navy proper, I could take the high school equivalency exam while I was in there and be eligible for the GI Bill. And that’s what I did.

“I did well in the navy in everything but manual labor. I would not have been a good airplane mechanic. They made me a storekeeper, and I learned how to type, which was invaluable in a future occupation, and they sent me to Norman, Oklahoma, for a couple months for some kind of advanced training. And then the Korean War ended, and everything froze. I ended up in Pensacola, Florida, where there were seven hundred Baptist churches and one bookstore. But at the base was a great library, and there I first read Hemingway, Fitzgerald, people like that.

“While I was in the navy, I met a guy from Marietta, Georgia, Henry Whiddon, who was a painter in civilian life. He would paint in the back of my storeroom, and my passion began to change from comics to painting. I thought I could be a painter.

“I was twenty years old when I got out, and because of the GI Bill, I could go to any university I wanted to, as long as it was government-approved. I wanted to go to Paris. In 1951 I had seen the movie American in Paris, with Gene Kelly. He was a Mick, and he was painting, and he had Leslie Caron, and I wanted to go there, but I couldn’t afford it. Even then, in 1955, what I got from the GI Bill after the Korean War was $110 a month, and out of that you had to pay tuition, rent, and food. I had been working since I was sixteen, and I didn’t want to have to go to school and take some job as a waiter too.

“This is how everybody’s thinking had changed from what the soldiers coming out of World War II did and what those of us coming out of Korea did with the GI Bill. It was only a matter of a half a generation.

“It wasn’t just Ted Williams who had to go back into the armed services. Korea was five years after we were all dancing in the streets on VJ-Day. And guys from the neighborhood got killed, because that’s the kind of neighborhood that fought both wars. They didn’t profit from them. They fought them. It has to be stressed, not just in Brooklyn, but all over: what ended in the summer of 1945 was a fifteen-year period of deprivation, which included the Depression. The guys who didn’t have work in 1934 or 1935 found work with a rifle in their hand, and when the war was over, they just wanted to marry the girl they left behind and have a home with a backyard.

“By the time of my generation, there was a shift to get an education rather than to buy a house in the suburbs.

“Reality had sunk in. This is the ultimate boredom. You needed a car and gasoline. It was hard. So rather than use the GI Bill to move, which is what we did after World War II, we felt the important thing was to get educated, and then you could make some dough. My brother Tom was two years younger than me, and he went to City College with Colin Powell, and he went off to Northwestern and got a master’s degree in engineering.

“I went to Mexico City. Henry Whiddon, the painter I knew, had heard about Mexico City College. It had a very good arts school, and it was acceptable to the GI Bill. And it was a great place to be, because you had the typical mixture of young dopes—Ohio Staters going for the summer, who went down to Mexico to drink—and there were guys who had been in the Battle of the Bulge.

“We took courses in Spanish and English. When I arrived in Mexico City, all I could say in Spanish was, ‘Hello,’ and ‘Good morning.’ You wanted to take Spanish because you were living there. And one of the accidental benefits of learning a foreign language is that you really learn about your own language, which is why all classical education includes Latin or French or both. The Latin helped me with the Spanish, so I learned fairly quickly how to talk my way out of things, like if I walked into the wrong cantina. And Mexico City College had a very good writing instructor by the name of Ted Robins. He was good in terms of pushing us to do more than just show up. It was a great decision to go there; between the vowels of Mexico and the consonants of New York, I could get a sentence out of myself.

“While I was still in New York I had seen reproductions of the Mexican muralists José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera. After I began to think about becoming a painter, I went to see their actual work, and the one thing reproductions don’t show you is their scale. They are gigantic, overwhelming, and if you’re a kid, like I was—intimidating. In certain ways they turned me off to painting, and my instincts went to writing. When you come from Brooklyn, you’re never in love with the grandiose. Your neighbors won’t let you.

“I was more and more interested in narrative. I wanted to say, ‘This happened, and this happened, and as a result, this happened,’ but I couldn’t figure out how to tell a narrative with paint. And at the time the attempt to do so was sneered at. To art critics there was nothing worse than Norman Rockwell, who told stories in paintings. It took a long time for people to realize he was valuable. So writing more and more began to interest me, and you write the way your heroes wrote, so I wrote like Hemingway and Fitzgerald. My teacher at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, Burne Hogarth, said, ‘There are four stages for every artist. Imitate, emulate, equal, and surpass.’ I wrote it down at the time, and I tell that to students now. So in the beginning it was all imitation, and somewhere in there I discovered James T. Farrell and Studs Lonigan, and there I began to see that I didn’t have to write about bullfighters. There were subjects right up the block in Brooklyn to write about. And then I discovered the Beats. When I got home from Mexico in 1957, I had read the first book in English by Carlos Fuentes, and in 1958 I read an excerpt of On the Road in The Paris Review. It was in The Paris Review that I read Philip Roth for the first time. So I read this excerpt from On the Road about Kerouac being on a bus going into Mexico, and I had taken the same bus trip. And then the novel came out the following year, and I was living in the East Village then, and these guys were living all around the place. The first time I ever saw Kerouac, he looked like Frank Gifford, a big, handsome guy dressed like a lumberjack. Too self-conscious, if you came from Brooklyn.

“In a way all of it went back to Brooklyn. I was shaped by it, but when I think back about the important things, one was the unleashing of this amazing optimism that was in working-class Brooklyn after the war, and it was underpinned by the GI Bill. The optimism said, ‘This is America. You can be anything you want to be.’ And that meant everything. You could be a doctor or a lawyer—or, if you were really lucky, a sportswriter: you could go to the games for free and get paid for it. All those possibilities were there. And it was a very rich time in the newspaper business. You picked up a paper, and there, writing about sports, were Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, Frank Graham, W. C. Heinz, Willard Mullins’s cartoons. It was like a feast, a very high level of work. It was no accident they called them sportswriters, not sports reporters. So all of that was feeding into discovering literature without a teacher. I’m convinced now that all education is self-education, that every decent writer is an auto-didact. But I didn’t know any of that then.

“You look at the sheer accidence of life, and I think emotionally of the optimism at the end of the war, the GI Bill that said, ‘You can do it,’ and I think of Robinson. We didn’t have a phrase like ‘role model,’ but that’s what he was. We knew from reading the papers what he was going through, particularly the first year when Chapman and the Phillies, the fucking assholes, taunted him and threw a black cat out onto the field. And you thought, If he can put up with that crap without exploding, so can we. So it began to shift so you didn’t fight at the drop of a hat, didn’t have to prove what a tough guy you were every waking hour. And yet there was a toughness around that was also different from what you have now. The real tough guys never talked tough. They were tough, and everybody knew it. They weren’t going around showing what tough guys they were, like Dick Cheney and those other pricks who couldn’t punch their way out of a schoolyard.

“All those things made me understand other things, made me understand the other immigrants, made me understand what people had overcome without self-pity. That was a key thing too. I never heard my father curse his fate at having lost his leg. A couple times he slapped the wooden leg—he couldn’t express himself very well, but that was a Belfast Irish thing as well as Catholic. Seamus Heaney has a poem about Northern Irish style called ‘Whatever You Say, Say Nothing.’ There was a great holding back about the most intimate things. I never heard him say, ‘I could have been a contender.’ And it doesn’t mean he didn’t feel it, but he wasn’t going to say it to his kids. And my mother had this other sense of time, which was not that things would get better tomorrow. She wasn’t naive. But they will be better the day after tomorrow. There was a sense that there was a future tense, that you were going somewhere, that each life had a narrative, and we—the Americans—were the lucky ones. We didn’t have to put up with the kind of bullshit that mutilated some of these people in the old country, wherever the old country was, be it Calabria, Sicily, Poland, or Belfast. It was going to be better, and those promises that America gave those people were kept. It wasn’t some right-wing bullshit. The right-wingers were the ones who tried to prevent it.

“Everybody’s story is different, but I bet most of them would have a similar pattern. While I was in the navy, I saw the movie Roman Holiday, with Gregory Peck and Eddie Albert. Peck is a newspaperman in Rome. He has an apartment where the bed folds up in the wall, like in a Marx Brothers’ movie. He never seems to work. He rides around on a Vespa all over Rome, and he’s got Audrey Hepburn, and that was the other formation of another way to live a life. The movies gave these visions of possible lives to the young.

“On June 1, 1960, I began at the New York Post. The Post was my favorite paper, because it had stood up to Joe McCarthy, stood up to Walter Winchell. They did a twenty-three-part series that basically ended Winchell’s career. Every day they had a sidebar box, right out of Winchell, called ‘Winchell’s Wrongos.’ ‘FDR will not run for a third term.’ It was wicked and awful, but great fun. And a great corrective.

“Jimmy Wechsler had brought out a book called Reflections of an Angry Middle-aged Editor, a terrible title, but I read it. One of the chapters was on journalism, and I wrote him a letter. I asked, ‘How do you expect to keep the vitality of newspapers in New York when you’re getting all these reporters who go to the Columbia School of Journalism and then go to work on the paper, who have never lived in New York?’

“He sent me a note, ‘Thank you for writing. Have you ever thought about becoming a newspaperman?’ And I had. I called him and we had lunch, and by the time we finished he offered me a tryout. They kept me on the tryout for the legal extent they could under the guild contract, which was three months. It was June, and they did a lot of tryouts then because they had a lot of people going on vacation. After the three months, they asked for an extension, and the guild gave them one more month, and then they hired me full-time.

“In between I was being taught how to do this. I had not gone to journalism school. I didn’t even know how to slug a story. I didn’t know how to do anything, but I had these amazingly good editors. The assistant night city editor was Ed Kosner, who was younger than I was and later went on to Newsweek, Esquire, and the Daily News. He took pity on this dumb goy in the corner. Other people were there, particularly Paul Sann, who I didn’t see until he came in at six in the morning, but he was the real ball-breaker who made me into a newspaperman. He was amazingly smart. He might have graduated from high school, but barely. They were proving a point with me, that you could make anybody into a newspaperman. If you had the passion, it didn’t matter whether you went to journalism school.

“Ike Gellis was the sports editor, and he was fun. There were a lot of wonderful drifters who would come in and out, guys would get drunk, throw a typewriter out the window, move down to the Journal-American. It was the end of the Bohemian culture that newspapers had. Once you get to 1970, the newspapermen were getting paid what they deserved, and then they became suburbanites. Back then, the wife would throw the guy out, and he’d end up at the Hotel Earle in Washington Square with the alto sax players. It was a wonderful time.

“There were seminars every morning at the Page One Bar, where everybody’d go at eight o’clock and wait for the paper to come out at nine. All the older guys would go through the paper and turn to you and say, ‘You can’t write a fucking lead like that. For Christ’s sake, this is the way.’ It was apprenticeship like at the navy yard, an apprenticeship like Leonardo at Barrochio’s studio, learning how to paint an eyelash.

“Again I was lucky. Had I gone to the Times, which also had its Bohemian element, I might have gotten stuck in school sports for four years instead of covering three stories a night and writing captions in between. It was a great, great school, and I tell the kids at NYU, ‘Whatever you do, get a job on a daily paper somewhere. Even if you want to work on The New Yorker, start on a daily and become fearless at the typewriter.”