IRELAND ALWAYS WAS AN IMPOVERISHED COUNTRY BECAUSE THE English Protestant majority, which ran the country, made certain it stayed that way through its laws, which not only prevented industrialization but barred Catholics from owning land, reducing the bulk of the Irish to peasant status. They could only rent, and between 1740 and 1840 the rents continued to rise until they had to sell their wheat crop to pay the rent, leaving the Irish Catholics to live on a diet of potatoes.

England, whose aristocracy historically treated the Irish little better than the czar in Russia had treated the Jews, passed a law in 1838 that shifted its responsibility to care for the poor from the government to the landlords, who figured out it was better for them economically to kick out their tenants and switch to sheep and cattle grazing. When a tenant couldn’t pay rent, he was evicted.

Between 1845 and 1847 the Irish potato crop failed, and almost half the Catholic population either died or left. Most—half a million—went to America, only to find that the Protestants who hated them in England also hated them in America. It was not uncommon to see NINA (NO IRISH NEED APPLY) signs in shop windows.

The Irish in America worked menial jobs. Three out of four Irishmen were unskilled laborers.

The Irish were only accepted after the influx of Jews, Slavs, and Italians, as hostility shifted to the newer immigrants. At the turn of the twentieth century, the Irish became cops and firemen, lawyers and politicians. The Irish political boss would ask, “What do the people want?” And he would do his best to provide it, whether he was honest or crooked. Thus the Irish were able to lift themselves up through politics—much to the Protestant majority’s disgust.

Many of the Irish who lived in Brooklyn were rough-hewn, tough guys who lived hard, drank hard, and fought hard as they scratched out a livelihood. John Ford, a kid who grew up on the streets of Flatbush, started out in a gang, but maturity and the army provided him with a route to middle-class respectability.

On September 31, 1939, Michael Ford, a sailor, jumped 250 feet off the deck of the Brooklyn Bridge into the East River, swam to shore, walked into a South Street saloon, and ordered a drink. The article in the New York Times the next day went on to say that he had a laceration of his left leg, which he dismissed as nothing, and that he was then taken to Bellevue Hospital to have his head examined.

John Ford, Michael’s son, a Brooklynite most of his life, said that his dad and his dad’s five brothers were roustabouts, guys just trying to make a living.

John, who was born in 1934, was something of a hard-ass himself. A member of a small gang called the Irish Dukes, John Ford and his buddies spent their childhoods drinking, making mischief, and getting into fights. After skipping school almost every day for two years, he dropped out of Boys High School in the eleventh grade, but after serving in the navy during the Korean War, John Ford took advantage of the GI Bill and went to college at night while working for the phone company and running a bar he owned in Flatbush. He got his associate’s degree from Brooklyn College and his BA from Pace College—after first getting a diploma from the school of hard knocks.

JOHN FORD “I can’t tell you much about my father’s father, Simon Ford, except that he was born in County Cork, and he left Ireland because the Black and Tans [Royal Irish Constabulary Reserve Force] were after him. The rumors were he was fighting the British. He went over to London, got a job on the ships, and then he jumped ship in New York harbor and swam ashore. For the rest of his life occasionally he would disappear because he would get this inkling the Black and Tans were after him.

“My mother’s parents came from Heidelberg, Germany. She came by herself when she was sixteen. In them days you had to have a sponsor, and she went to live with her cousin. She was a domestic servant most of her life.

“They settled in what they now call Bedford-Stuyvesant, but we always called it the Ninth Ward. Nobody ever called it Bedford-Stuyvesant. I didn’t hear it called that until it became infamous, if you know what I’m saying.

“I was seven when the war started. My father went off to war, and my mother was working upstate New York, so I lived with my grandparents. They lived above a glass store. The building had three stories. They had five children in the war. In them days you used to put stars in the window, and a Gold Star was put up when my uncle Junie was killed.

“My father was born about 1916. Before the war he just knocked around. He worked on the docks. He was a bartender. Whatever work he could pick up. It was the Depression, and he told me he would shovel snow working for the WPA. He would sign up on one side of Prospect Park and start shoveling snow, and when the boss turned his back, he’d run across to the other side of the park, sign up there, and start shoveling snow. Running back and forth, he got paid twice.

“One of the jobs he had was the head waiter for the Bluebird Casino in Coney Island, in the days when it was bustling. During lunchtime he told me he would give the wealthy-looking customers the dinner menu, which was twice as much as the lunch menu, and pocket the difference.

“He was friends with Milo the Mule-faced Boy, who had the ugliest face you’d ever want to see. After Milo quit and ran across the street to join the competition, he became Milo the Dog-faced Boy. Milo lived in my neighborhood. He even had a girlfriend.

“My father was an amazing man. He never got past the third grade in school but from a third-grade education he became an officer in the navy. They wanted to make him a captain but he didn’t feel he had the writing skills, and when he came out, he went into the MSTS, Military Sea Transportation Service, which used to bring the troops back and forth from Korea. He was a chief steward on the USS Muir, which meant he was the guy who fed everybody. He was in charge of the whole thing.

“I showed you the article in the New York Times about the time my dad jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge. The headline of that article was ‘Tipsy Sailor Leaps.’ His version was that he wasn’t drunk, that he was sitting in a bar with his friends, and his bookie was in there, and they were talking about betting.

“The guy said, ‘If I bet you $100 you wouldn’t jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, would you do it?’

The Reinhold wedding. Ford’s parents are seated in front. His father once jumped off the Brooklyn Bridge and lived to tell about it. Courtesy of John Ford

“‘Sure,’ he said, so off they went. They got in a cab, drove halfway over the bridge, and bing, he jumped over. He said he tied a towel around his crotch. He lived, but the guy never paid him. He said, ‘I don’t pay off on bets like that.’

“It’s a wonder my father and his five brothers didn’t wind up in the river or get their legs broken. One was badder than the other, roustabouts, guys just trying to make a living.

“Mostly my father was working the ships. He used to have this big, long coat with seven or eight pockets. He would come home all filled up with whatever he could take. He was offered a job on the docks as a checker, which was a big job, but checkers were tied to the Mob, so he turned it down. He figured he’d wind up in jail, because the guys with the bent noses don’t take the rap. He does.

“The last job he had before he retired was working as the chief oiler of the presses of the New York Times. He went around oiling things. They liked him so much they gave him a management title.

“I have no idea how my father and mother met. She was a German Protestant, and he was an Irish Catholic, which didn’t sit well in them days. My father was the patriarch of the clan, so they didn’t mess too much when he was around, but she was never treated as one of the group, nor did she want to be part of that group, because they were hard-drinking, tough people, and she was a gentle person.

“I was born in September of 1934 in Bedford-Stuyvesant. I was baptized in the St. Peter Klaver Church. My parents were separated when I was a kid, and I didn’t meet my father until I was seven years old. I lived in East Flatbush with my mother. The area was all-white. The dividing line in Brooklyn was Bergen Street. Blacks never went past it.

“I belonged to a gang called the Irish Dukes. We had ten guys. It wasn’t huge, but it was big enough. We would sell chance books for a quarter so we could buy our jackets and put IRISH DUKES on the back. We used to fist-fight with the Garfield Boys and the Park Slope Boys. They’d come down in a mob and nail a couple of us. Wasn’t anything personal. Some of them guys were my friends. But if you didn’t know how to fight, you were in deep shit. Everybody was in the same boat. Everybody thought that was the way you were supposed to live.

“I remember when Jackie Robinson came up to the Dodgers in ’47. The Irish were pissed off. When the blacks came to Ebbets Field, they didn’t flock there. They came tentatively. In those days everybody was a ‘nigger.’ They asked, ‘Who’s going to sit next to all these niggers?’ That’s the way the people thought in them days.

“When I was a kid, Dixie Walker was my favorite player, but they got rid of him because he was the biggest racist on the club. That’s why they traded him. He wouldn’t play with Robinson. Dixie was the People’s Choice. That was our man. But I loved all the Dodgers. They were all super players. Any one of them was an all-star. Our motto was, ‘Wait ’Til Next Year.’ We were loyal fans. I loved the Dodgers.

“I was going to Boys High, which was in a black neighborhood, and I had become friends with a black kid by the name of Hughie DeShan, and we were such good friends that Hughie used to come and swim off the piers with us. We even made Hughie an honorary Irish Duke. He used to come to our dances on Sunday night at St. Teresa’s. He was the only black guy there. He used to do the Hucklebuck, and those white girls would go apeshit. At the same time we were calling them ‘niggers.’ Because you didn’t know any better.

“There were a good number of blacks at Boys High. If you went to the bathroom, you had to fight your way out. One time after school I fought this one black kid—another friend—and two hundred people stood around and watched. After the fight was over, we were still friends. But you had to fight. You didn’t back down. I never backed down in my life. That’s the way it was.

“So the people in the bars where I hung out—the Irish and Italians—were upset when Robinson came to the Dodgers. They were really outraged. But when he started playing, when they saw what kind of player he was and how he conducted himself, he was our hero. If he had done half the shit these black players do today, they would have found him dead someplace. He was the only one, and we would have gotten rid of him and that would have been the end of the experiment. That’s just the way it was. The element I hung around with was not the intelligentsia. We were just knock-around saloon guys. But when Rickey picked him, he picked the right man.

“My father, an uncle, and another guy ran a parking lot outside Ebbets Field right next to a bar that was behind left field on the corner of Montgomery and Sullivan Streets. As kids, we used to sell the Dodgers scorecard and the Brooklyn Eagle. Then we sold Who’s Who in Baseball, and then we worked for a guy who gave us a board with buttons, hats, bats, and pennants, and we’d sell them, and he’d give us a cut. Pretty soon we figured out, ‘Screw him,’ and we made our own boards. We went down to Chinatown, and we’d get buttons with the team name or a player like Robinson or Newcombe, and we’d buy a row of ribbons and put a ribbon on each button, and we’d buy miniature bats, pennants, and we sold them ourselves. If we were too near the stadium, sometimes a cop would chase us, so we’d go down near the subway on Flatbush Avenue, which was right near Hugh Casey’s bar. Remember Hugh Casey? He was the original relief pitcher. I heard he blew his brains out.

“My father knew the traveling secretary of the Dodgers, Bert something, and he used to let me get into the game through the press gate at the rotunda at Ebbets Field. If I got caught doing something wrong, my father made me work the parking lot. One day I snuck into a warehouse across from our house on Park Place. My buddies and I went in through the skylight, and we robbed the place of pencils and other shit. Somehow my father knew it was me, so my punishment was I had to go to the parking lot every day while the Dodgers were in town and help park cars.

“In ’53 my father and I decided we’d make some money scalping World Series tickets, so we paid people $20 to get on line and get us tickets. You were only allowed a couple tickets apiece, and I spent $200 buying tickets for the sixth and seventh games of the series, and wouldn’t you know the Yankees won it in five games, and the series never did come back to Brooklyn. And I was going to use that $200 to get married.

John Ford at his first communion from St. Teresa’s, 9th Ward, Brooklyn. Courtesy of John Ford

“As a young boy I went to St. Teresa’s, a parochial school, and in them days the nuns didn’t screw around with you. They’d hit you on the hands, smack you on the head. If you missed church on Sunday, you better have a note. If you were absent, you had to be half-dead. They made you toe the line.

“The better days of my life were spent down in Sheepshead Bay, where the fishing boats used to pull in. Piers stuck out into the bay, and every gang had its own pier. The Pier 9 Boys were from Sheepshead Bay. The Garfield Boys were from South Brooklyn. We had our pier. We didn’t have a name for it. It was just ours.

“When we were thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, we would dive for coins. People used to go down and buy fish off the boats, and others would stroll along Sheepshead Bay, and they’d throw money into the water, and we’d dive down and stick the coins in our mouths. We could be treading water for a half hour.

“We used to go into the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens and swim there naked. People would stroll by, and here were these raggedy-assed kids, and the cops would chase us up the back. We used to sneak into Girls Commercial School and swim in their pool. There were so many things we did. When we were fourteen, fifteen, we would drink Five Star muscatel. It cost 35¢ a pint. We would give the 35¢ to one of the crazy Smitty brothers—they supposedly hung a black guy from a lamppost one time—and he would buy the Five Star, and we would give him a couple of swigs, and then we’d finish off the rest, and we’d stagger home. Nobody thought it was odd. It sounds like the Dead End Kids, but we were living it, and we didn’t even know it. My mother was working, and my father was working. I never went home to a house with anybody in it. I was a latchkey kid, but I never felt neglected. You just went your own way. I used to go over to my friend Johnny Ryan’s house, and his mother would let us smoke. We were nine or ten. She used to get us cigarettes. We’d go into the basement of her house and crawl into the basement of the adjacent grocery store, and we’d steal eggs and bring them back to her.

“During that time, around 1947, 1948, there was a polio epidemic, and they closed the beaches at Coney Island and Riis Park. We always thought we were immune to polio, because there were sewer pipes near where we swam, and shit came floating out of there. None of us got polio, but two of the Irish Dukes got MS.

“Nobody had any money. Of course not. We put oilcloth in our shoes after the big hole came. We never paid for transportation. We all hung off the back of the streetcars. We’d open up the back window, and everybody would crawl in. We never paid on the subway. We used to go down to Park Place in Brooklyn, go up a girder, cross another girder, come up under the station, go upstairs, and take the train to Sheepshead Bay. Coming back we went in the back, crawled up a girder, climbed over a fence, walked along the fence, jumped up onto the station platform, and caught the train home. We never paid—nah. The trolleys were 3¢ with a penny transfer, but we still hung on to the back.

“We didn’t pay to go to the movies either. There were two movie theaters, the Savoy and the Lincoln, which were right next to each other on Bedford Avenue. The Savoy had first-run movies and the Lincoln second-run. The only way you could get into the Lincoln was to have one guy pay, and then he would open the side door and everyone would run into the place. To get into the Savoy, we would go next-door and open the cellar door, go down into the cellar, and we’d crawl out and come out into the bathroom of the theater. We’d go in the back, climb up stairs, and wind up on the roof, and from the roof we could go into the balcony. The problem was the balcony was for adults only. We’d get on our bellies and wiggle, like a snake, and if they saw us, we’d run away and hide.

“I didn’t like school. I used to come in late every day for a year and a half. If you were marked absent, they would send a card home. I would show up every day, but I’d skip seven classes. I would get seven cut cards a day. I had no interest. You’d have figured after six months they’d have wised up. As it was, a group of five or six of us would come in late every day, and we’d go up to Jackson’s Pool Room and shoot pool. Boys High was in the black section of town, and if the people there saw the teacher coming into the pool room to check it out, they’d hide us in the back. We would go to the movies downtown or play basketball at Girls Commercial. That’s how I spent my teen years.

“When I was sixteen, I hung out at a dangerous place called the Snake Pit, on St. Mark’s Avenue. We were kids, but we had draft cards that said we were thirty-five, and as long as we had a draft card, nobody gave a shit. The Snake Pit was just down from Bergen Street, so we used to have black guys come in there, but they were our buddies. One time a gang came in there after the Irish Dukes, and there were only two of us there, my friend Pete and I. These two giant black guys, our friends, said to us, ‘You stay over there.’ They said to the gang, ‘Let’s go outside, boys.’ And then they went outside and beat the shit out of the two gang members. We sat there drinking our beers when they came back in and said, ‘That’s it, guys.’

“I had friends who became gangsters. My cousin’s husband, a cop, tried to screw with my friend Andy Jukakis, and Andy sliced the side of his head with a knife. Later they found Andy dead in a lot. There was this guy Tommy Cronin, who we called T-Cro. He had his own gang. He died when he went into a back room and blew his brains out. Then there was Charlie, my really good friend. We hung around a lot and we could have gone either way.

“Charlie, who was a nasty son of a bitch, traveled with a gun. I can remember being in a bar on Flatbush Avenue when Charlie walked in. He said to the bartender, ‘I want you to leave.’ The bartender said, ‘What do you mean?’ Charlie said, ‘If you don’t get out of here in five minutes, I’m going to kill you.’ The guy left, and Charlie went behind the bar and served free drinks to everybody. I left before the cops came.

“We used to play in our Friday-night card game. We played at this guy’s house, and come to find out he was queer—that’s what we called them in them days—and Charlie murdered the guy. He beat him to death.

“Charlie was sent to Rikers Island, from where he and a few others escaped. They swam across the East River to LaGuardia Airport. He then tried to hold up this doctor’s office in Bay Ridge, and he got shot. They sent him back to Rikers, and again he escaped, but this time he didn’t make it. They found him floating in the Narrows. That was the end of Charlie.

“I was in so many tight spots that I don’t even like to talk about them. I could have gone either way. It doesn’t take much to take the wrong turn, and once you make that turn, it’s hard to go back. The navy saved my ass to a certain extent. Having a family, going to school. And again, my father. He was my hero in life. I was the only guy in our family who ever went to college and graduated. He was so proud of that fact that I had to graduate.

“When I was seventeen, in 1951, I was walking down Franklin Avenue with my friend Joey Preston, when he said, ‘I’m going to join the navy.’ Joey had three brothers in the navy already. I said, ‘I’ll go with you.’ But we had to wait until February for Joey to turn seventeen. And my father had to sign for me. What the hell? It was better than the half-assed job I had working in a stationery store.

“Joey and I went in. The Korean War was still on. Joey got sick, so we didn’t graduate boot camp together. I went to radio school, and I was assigned to the USS Ross, a destroyer out of Norfolk, and I spent my entire military career on that ship. We were never shot at. We took a world cruise. We started in Norfolk, went past Florida, went through the Panama Canal, came back around the Suez Canal, and visited many, many countries. We were relief for the Seventh Fleet.

“About the time we showed up in Korea the armistice was signed. I can remember going up the Yalu River. The captain did this either because we earned an extra ribbon or just to be there.

“One day an officer said to me, ‘John, I see you don’t have a high school diploma. Would you like to take a test?’ I sat and took that test, and I did very well, and when I got out of the service, they had passed the GI Bill, which was the savior for this country in a lot of ways. A lot of people went to school because of it. I said, ‘Let me try this and see what happens.’

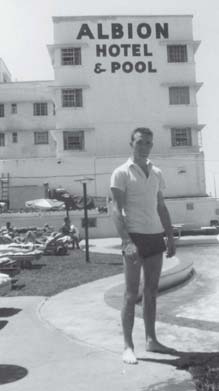

John Ford at the Albion Hotel in Asbury Park, New Jersey. Courtesy of John Ford

“I was working for the New York Telephone Company during the day, and I went to Brooklyn College at night, so I got half-pay, plus they were paying me $9 a credit to go. And I kept going until I got an associate’s degree. I had to find a college that would recognize my credits from Brooklyn College, and Pace University down on the Bowery was recommended to me, and after seven and a half years of night school, I got my BA degree.

“One reason I did it was I had a family to support. My wife had had six kids in nine years, and I needed a better-paying job. I thought I could make some extra money, so while I was doing all of this, my father and I bought a bar on Nostrand Avenue and Clarkson called Ford’s Bar. I owned it for a year and a half, but I didn’t make any money. I was afraid if I didn’t sell it, I’d end up in jail. Fuggedaboutit.

“One time this guy was giving me a hard time, and we went outside, and we were rolling on the ground and I was smacking him in the head, when a bus came by and almost ran over his head.

“I was behind the bar on Fridays, and these local guys, who would eventually wind up in prison, came in, and they were sitting there when this black guy walked in. The bar was right down the street from Kings County Hospital, which had a lot of black employees. When he came in, everyone treated him with respect, didn’t say anything, but then he said to me, ‘I’d like to buy these guys a drink.’

“Those guys were not interested in him buying them a drink, and I told him so.

“‘Why, is it because I’m black?’ he asked.

“I said, ‘It has nothing to do with your being black. The guys don’t feel like having a drink.’

“So he pulled out a knife. We backed him out the front door, and about eight or nine of us ran down the block after the son of a bitch, and we caught him, and down he went, and one guy kicked him in the head. One of the other guys suggested taking the guy down to Sheepshead Bay and throwing him in the river.

“I said, ‘Stop. No no no.’

“One of the guys, Peter Lawler, said, ‘I’ll wait here and tell the cops he pulled a knife on us. We’ll get him locked up. We’ll do it legal.’

“I said, ‘Good.’ They would have killed the guy.

“We went back to the bar, and the cops locked both the black guy and Lawler up. We had to get him a lawyer.

“Three weeks later Lawler was in the bar, and three big black guys walked in. My uncle was behind the bar. One of the black guys says, ‘My little brother was in here a couple weeks ago when somebody beat him up.’

“I thought, Holy Geez. My uncle, who was a tough son of a bitch, would have dropped two of them. And there sat Lawler at the end of the bar. I said to him, ‘Shut up. You keep quiet.’ I went outside, crossed the street, and phoned the cops.

“I went back to the bar and told my wife to get out and go back to the car. Eventually the three black guys left and started to walk away when this crazy bastard Lawler went outside, picked up a garbage can, and started running after them.

“‘Are you guys looking for me?’ he said.

“I locked the bar door.

“Two months later Lawler came in. I was behind the bar. He was pissed at me for locking the bar. I said, ‘Pete, are you crazy? You went after them guys with a garbage can. What do you expect me to do? I couldn’t have done shit.’

“He threw his keys at me, and he leaped over the bar at me. I got him around the neck, and I wrestled him to the ground, and his head hit the ground, missing the step going into the back room by half an inch. It would have cracked his skull open and killed him. I told him, ‘Don’t ever come in this place again.’

“This was what life was like in Brooklyn. Just growing up there was an adventure. But we didn’t know it was an adventure. It’s only as you look back and say, ‘Look at all the crazy shit we did.’”

After John Ford got out of the navy in 1955, his parents decided it was time to move out of their apartment in the Ninth Ward (Bedford-Stuyvesant). The economy was booming. People were finding work. Levittown on Long Island was opening, and people for the first time had an opportunity to move out of their small apartments and move into single-family homes with grass and gardens and two-car garages. John Ford, unlike many who moved to the suburbs, didn’t want to leave Brooklyn. He had saved $75 a month from his navy pay, and his family and his parents moved into a two-family home in Flatbush.

John Ford today. Courtesy of John Ford

JOHN FORD “My father was working. My mother was working. I was working. If you had an opportunity to buy a house—it was unheard of—so we did.

“When we owned that two-family house, Flatbush was a really nice neighborhood. There was a housing project there, but it was middle-income, mostly white, a good place. There were seven buildings, and Mayor Lindsay bought them and made them into subsidized housing. Little by little, poor blacks moved in there, and the place went to hell in a hand basket, just went down the tubes. I don’t know if people panicked. They probably did, and then they started leaving Flatbush. And I was like the last guy to leave. I told myself, I’m not leaving here. But my kids were going to parochial school at St. Edmonds, and they started having problems. There was crime. They were getting hassled. Bikes were stolen. I then said, ‘I gotta get out of here.’

“The blacks who first moved in were hard-working people, because now they were getting a chance to buy houses of their own, which was unheard of in their era. First the poor whites bought them, and then the blacks. But when blacks started selling to blacks, that was like the plague. The housing values started going down, and I said, ‘I better get out of here while I can get something.’

“I moved down near Sheepshead Bay. I bought a house on Avenue U. I held on to that house until around 1990, when I sold it to Asians. I was separated at the time, and I decided to move to Florida.

“I wouldn’t have traded Brooklyn for the world. I’m glad my kids grew up there. All my kids are college graduates and successful people. One of them is a millionaire.”