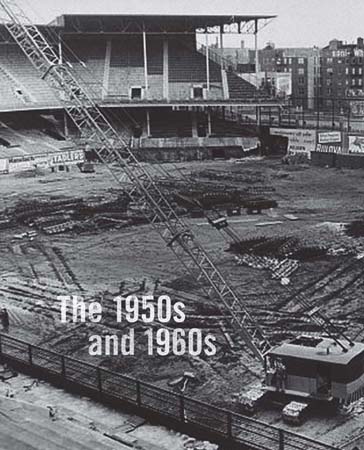

FOR BROOKLYNITES WHO LOVED THEIR DODGERS, THE YEARS between 1947 and 1957 were magical. Six of those seasons Dem Bums won the National League pennant, and during most of this period the Dodger stars remained constants in their lives. Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider, Roy Campanella, Pee Wee Reese, Carl Furillo, Gil Hodges, Don Newcombe, Clem Labine, and Carl Erskine were the bullworks of the dynasty.

For John Lawrence Mackie, who grew up in Sheepshead Bay, the player he admired most was the third baseman, Billy Cox. In 1949, when he was five, Mackie developed polio. After he lost the use of his legs, he was treated by an Australian nurse by the name of Sister Kenny, who came to the United States prescribing a polio treatment that has been scoffed at by mainstream doctors and by history. But according to Mackie, Sister Kenny’s treatments enabled him to walk again, and when he left the Jersey City Medical Center under his own power, a reporter from the Brooklyn Eagle interviewed him. When asked what he wanted to be when he grew up, Mackie told the reporter he wanted to be “the third baseman for the Dodgers, like Billy Cox.” A correspondence between Mackie and Cox resulted. Mackie, who is now sixty-two, has never forgotten his childhood hero.

Cox left Brooklyn at the end of the 1954 season, but Mackie’s love for the Dodgers continued. Baseball in Brooklyn during that era was as important to the residents as breathing the very air itself. It was the glue that held the borough together.

JOHN MACKIE “I was born on April 28, 1944, in St. Peter’s Hospital in Brooklyn. My grandfather Percival Mackie, who they called Percy, came from Scotland. He was a mechanic, a guy who grew up around horse carts, who eventually became an automobile mechanic. I don’t believe the man ever had a Social Security card or ever paid a nickel of Social Security. For years he operated a shop in his backyard. He got up in the morning and walked out to the shop and fixed neighbors’ cars. He got ten bucks here, five bucks there, and that’s how he made his way through life.

“He lived in Sheepshead Bay in a little house on East 15th Street, right off Avenue U and diagonally across from the old 61st Precinct. The Mackies were famous for noisy parties, and the cops would come over and tell them to quiet things down, and of course, they would never leave. They would become part of the crowd.

“My mother’s maiden name was Hawke. She was English and Irish. Her mother’s maiden name was Sullivan. Her parents were born in the United States, but their parents were born in Ireland and England. I don’t know why they came. I guess because they wanted a better life.

“My parents met in Yonkers in the 1940s. My mother was living with her first husband, and my father was operating a bus company there. They got together, and they got married in Hoboken, New Jersey, and they settled in the Midwood section of Brooklyn on Ocean Avenue between K and L. We lived in a place called the Ocean Castle, an austere-looking apartment house with small courtyards. I can remember trolley cars going past the door.

“In 1949 there was a Brooklyn polio epidemic. The epidemic spread throughout the New York metropolitan area, but people were very parochial in those days. Things only happened in Brooklyn. There was no place else. Anyway, I contracted polio.

“I couldn’t walk. I had weakness of the limbs. Our family doctor got me admitted to the Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan, and I lay in bed for two weeks and did nothing, because they didn’t know what to do. Salk had not yet come out with his vaccine, and even if he had, it was already too late for people who had contracted it.

“Polio was a mystery to physicians. However, an Australian nurse by the name of Sister Elizabeth Kenny found a way to treat polio and she brought her methods to the United States. She was given one whole floor at the Jersey City Medical Center. Though she was deemed a quack by the medical profession, she had wonderful results with her methods, and eventually she became state-of-the-art.

“Her argument was, ‘If you don’t do anything with these limbs, they will atrophy further and waste away to the point where they won’t be able to do anything.’ So she would take wool, thick army blankets, cut them into long strips, put them in a barber towel machine, and heat them very hot, and then she’d wrap the limb with them, go up and down the leg to relax the tissues inside the leg, and then manipulate the leg.

Boy standing on table being examined by Sister Kenny. Library of Congress

“I can remember as a kid lying in a room with a big, bright light, and all these orderlies would be manipulating my limbs, making my legs work, bending my back, doing all these contortions with me to keep the limbs and muscles from atrophying. It was absolute agony. I remember screaming. It was as if I was in a torture chamber. “I was there for several months. And then one day I woke up, and I was able to walk. I remember the first day I could run up and down the ward. I was cured. It was amazing. I was cured!

“I was released on Christmas Eve, and as a human-interest story, a reporter from the Brooklyn Eagle showed up and wrote an article with the headline ‘Boy Receives Wonderful Gift for Christmas.’ There was a picture of me being carried out of the hospital in my dad’s arms. The reporter said to me, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ I told him, ‘I want to play third base for the Brooklyn Dodgers, just like Billy Cox.’

“I received a baseball in the mail signed by the entire 1950 Dodger team. Everybody signed the ball. Cox sent it to me with a little letter. My father got back to him, and from that point forward I would get a Christmas card from Billy and Anne Cox and their kids from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. This correspondence continued until 1954, when he left baseball. In the spring of 1955 he failed to show up at the Cleveland Indians training camp. Al Rosen broke his pinkie, and the Indians, who had just gone to the World Series, needed a third baseman. They traded with the Baltimore Orioles for Cox and Gene Woodling, and Woodling showed up, and Cox never did. He went on a two-week bender, just vaporized, and he was out of baseball.

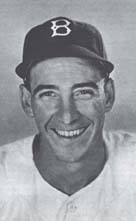

Dodger third baseman Billy Cox, hero to young John Mackie. Courtesy of Peter Golenbock

“Everyone had been amazed that I had been cured. My family was poor. There was no way we could have paid any amount of money to Sister Kenny, but my father wanted to thank her for what she had done. My father, who ran a Studebaker agency in Sheepshead Bay, drove a Studebaker all over Brooklyn and sold raffle tickets for a month, until one day I picked the winner out of a hat. Some guy won a brand-new Studebaker, and all the proceeds went to the Sister Kenny Foundation. In 1946 a motion picture was made about Sister Kenny. Rosalind Russell played the lead. [Russell was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress for Sister Kenny.]

“We lived in Midwood until about 1951, when we moved briefly to a little town called Valley Stream, on Long Island. My parents were no longer living together, and I lived with my mother and my sister. Then in 1953 we moved back to Brooklyn, to Sheepshead Bay, a little apartment in the basement of my older sister’s house. Her husband, a New York City fireman, had bought a home right off Emmons Avenue and they were glad to get the rent. My father, who didn’t live with us, paid. I was so glad to be back in Brooklyn! That’s what I identified with as a kid.

“Sheepshead Bay was the home of a large fishing fleet. Any number of piers ran along Emmons Avenue. Dozens of charter fishing boats operated from there.

“We swam in those waters, much to my mother’s chagrin. If she would have found out, she would have killed me, because she thought I would contract polio again because of the terrible polluted waters. I didn’t care. I swam in those waters, and we would fish, scoop up blue-claw crabs, bring them home and enjoy them.

“I went to elementary school at PS 52, which was on Nostrand and Voorhees avenues. The area was a mix of everything. I played with the Leuci kids, five or six houses down. The Melillos were across the street from me. The kids I played the most with were the Weilguses, Stanley and Lenny. They lived in a house adjacent to the service road of the Belt Parkway. We would paint a little box on the side of that house and play stickball, which was the street game of Brooklyn, and it was a home run if you could hit it over the Belt Parkway. I can’t tell you how many Spaldeens we lost.

“The Leuci family was interesting. Pasqual Leuci lived in a house that had a garage in the back. His father was an ice man. His truck would come along the street at night, and he’d park it. He had this big old wooden-body truck with the ice chutes on the side. He must have been the last ice man to cometh.

“And the old man didn’t speak English. He was truly from the other side. I’d go over on Sunday afternoon to the family gatherings. The mother and the aunts would be stirring this big pot of sauce. The wine would be flowing, and the old man would be plucking a mandolin, playing Italian music.

“The garage in the back was never used to house an automobile. It had a big wooden vat in the middle of it. The whole backyard was one big grape arbor. They took the grapes when they matured and brought them in, and they did the tarantella on the grapes with their feet in this big, wooden tub and made their own wine.

“The Weilgus family also was interesting. I was like a surrogate part of their family. I would go with them on evening rides out to the Rockaways, and maybe we’d stop and get an ice cream someplace. I learned an awful lot about Jews. I learned their songs. I remember being at a seder, and I wore a yarmulke. I knew the Hanukkah song. It went, ‘Hanukkah, Hanukkah, da da da da, top spins round, candle burns da da da da, it’s Hanukkah today, da da da da.’ In the shower I can do it better.

“At PS 52 most of the kids had names like Goldstein and Kammer. It was mostly a Jewish neighborhood because of an apartment complex built along Nostrand Avenue near Avenues X, Y, and Z, which became populated with Jews. I don’t recall Protestants.

“I went to St. Mark’s Church on Avenue X and Ocean Avenue. I was a very religious little boy. Even though I was a public school kid, I would get up every morning at some ungodly hour, like five in the morning, and I’d get on my bicycle and pedal all the way to St. Mark’s and attend a six A.M. mass.

“I was enthralled by the whole idea of religion and the sense that this was a good thing. I was so involved in the idea of the church that at one time I even considered growing up and becoming a priest. Then, when I was ten or eleven, I didn’t go anymore. My interest dwindled, and I would only attend Mass on Sunday.”

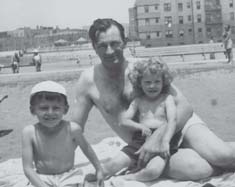

John Gilbert Mackie and his two children, John and Patricia, Brighton Beach, circa 1951. Courtesy of John Mackie

The main religion for Mackie and many of the Brooklyn kids at that time was the Brooklyn Dodgers.

JOHN MACKIE “Although my father and mother were estranged for as long as I can remember—my father didn’t live with us for most of my life—on Sundays he would come and visit my sister Patty and me, and take us out, and he would take us to Ebbets Field to a Dodgers game. He would bribe the ticket taker in the booth, give him an extra $10 to make sure he got us seats right on the third base line near Billy Cox. When I became ten and eleven, I would go to games by myself. I’d catch the subway from Sheepshead Bay and take it all the way down to the Prospect Park station and walk over to Ebbets Field.

“At one time one of their sponsors was Borden’s, and if you collected ten Fudgsicle wrappers or Dixie Cup lids, they would send you back a ticket to Elsie’s Grandstand. There was a pharmacy around the corner, called Littman’s. People would go in there and buy Borden’s ice cream, and as they walked away, they would throw the wrappers on the sidewalk or flip them in the trash can, and I would loiter in the area and collect all of the wrappers and lids and send them in. I even made a little business out of it. I would sell the tickets I couldn’t use to the kids in the neighborhood.

“When I went to the games, I would try to get autographs from the players. It was difficult. I knew where the players’ entrance was, but it was always crowded with people. If you saw one of the players a block away where they parked their car in one of the lots, they were reluctant to stop and sign for you, because that would cause a crowd to collect, and they’d have to stand there for twenty minutes. So what I did, I bought 2¢ postcards and addressed them to myself. I would wait for these guys and catch them as they parked their car either before or after the game, and I’d simply hand them the postcard. They’d put it in their pocket and keep moving. Then the next day in the clubhouse, they’d sign it themselves and in some cases other guys would sign it too, and they’d drop it in the mail. I had a number of autographs. I even got Willie Mays that way.

“I can remember the day I met Sandy Koufax. It was back in ’56. The Dodgers played the Milwaukee Braves in a doubleheader, and Sandy started one of the games. In ’56 he wasn’t the Sandy Koufax we all came to know. He was a young, promising pitcher with an amazing fastball, and he would have been great if he could have controlled it. But you never knew where this thing was going.

“He proceeded to get his teeth kicked in in the first two innings, and after the game I did my usual thing, hanging out near the parking lots, trying to catch the players and give them one of my postcards.

“I walked behind the right-field fence of Ebbets Field where there was an automobile dealership on the other side of Bedford Avenue. I could see Koufax walking toward a car. I trotted up to him. I was the only kid. There was no one else around. He let himself into this big, clumsy Jaguar sedan. I said, ‘Sandy, can I have an autograph?’

“I had the postcard in my hand. He looked at me with a look of scorn, derision, and anger, and he taught me words I had never heard in my life, words I know now very well, but I had never, ever heard them before. If he could have bitten my head off, he would have. He drove away, and I stood there just totally deflated. My mouth hung open for the next ten minutes. I thought, What the hell just happened here? That was a rude awakening after thinking all ballplayers were these wonderful, terrific guys.

“What I remember most about Jackie Robinson was how strong he was. The Dodgers were playing the Pittsburgh Pirates on a hot Sunday afternoon. There was no worse heat than the confines of Ebbets Field. Jackie came to bat with several runners on base, and I remember him turning on a pitch. He was wearing one of those wool uniforms they wore, and he was soaking wet, and when he turned, I could see the sinews of his arms and forearms, and the moisture and sweat when he made contact with the ball, and he hit a rope into the left-field seats. It was a line-drive home run, and it seemed like the ball never started to fall, just went over the third baseman’s head and stayed on a string straight into the seats. What a poke! And I thought to myself, My God, how incredibly strong this guy must be.

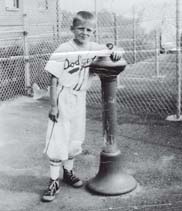

John Mackie in his Brooklyn Dodger uniform, the summer of 1952.

Courtesy of John Mackie

“Jackie was the tail that wagged the dog in that Dodger organization. He kind of got what he wanted. For whatever reasons, he was pretty indulged. Billy Cox years later told me he was traded from the Dodgers because of problems he had with Jackie.

“Every spring training the Dodgers would be trying somebody else at third, trying to find a replacement for Cox. One year it was Don Hoak. Another year it was Don Zimmer. He was like Rodney Dangerfield. He didn’t get no respect. But once the season started, Cox was back at third, and he played the season, and he was considered one of the best third basemen ever to play the game.

“In ’53 Junior Gilliam came up, and Robinson wanted to move to third so Junior could play second. Then Jackie wanted to play left field. But Cox was the yo-yo. Whatever was going to happen, he was the odd man out. And Billy resented it terribly. He thought he was a better third baseman than anything Robinson could have hoped for.

“Also manager Charlie Dressen didn’t like Cox, because Billy liked to drink. Cox and Preacher Roe, the Dodger pitcher, were pals. They roomed together, and they refused to fly. When the team would fly to Boston or to Chicago, they would sit on the train and drink beer from here to Boston or here to Chicago, and Cox would spill himself out of the train when they pulled into the city. Preacher Roe told me that Cox played third one day when he was totally loaded, and he said, ‘I never saw a man play third base so great.’

“In Brooklyn Cox and Roe and many of the Dodgers stayed at the St. George’s Hotel. There was a circular staircase that led from the upper level down to the main floor of the hotel, and that’s where the bar was, so when Cox and Roe would be sitting there at the bar having a beer, they knew if Charlie Dressen caught them there’d be hell to pay. They got the bartenders to put up gypsy curtains along the entrance to hide that area of the bar from the stairwell so Dressen couldn’t see them as he was coming down the stairs.

“They had an early-warning system, and when they were alerted Dressen was coming, they’d hide out until he passed through the lobby and went about his business.

“The Dodgers were my whole life. This was a sense of pride. I always looked at things deeper than my friends did. I said to myself, What are the odds of being born in this world where countless billions of people have been born, lived their lives, and died in abject misery, poverty, and disease, and how lucky can I be to be born in the United States of America AND in Brooklyn?

“There was this belief that this was God’s country, the promised land. This was the greatest place in the world to be. You wouldn’t trade it for Beverly Hills. My thought was, How lucky I am to be living here.

“The Dodgers were part of this grand scheme. They would validate the belief about this being the greatest place in the world, because every year the Dodgers either won the National League pennant or would come close, and of course there was that annual playing of our nemesis, the New York Yankees. It was the poor people of Brooklyn versus the rich guys from New York. We had this need to show them we could beat them, that their wearing fancy pinstripes didn’t mean a thing to us. We were a better team. True, for a lot of years we didn’t beat them, and you’d be saddened by it, but the attitude always was, ‘Wait ’Til Next Year.’ Somehow Brooklyn people found a way to rationalize the losses, and the next year the campaign would start all over again. It was a whole new ballgame, a new fight, a new battle, as we kicked and scratched and clawed to win a pennant so we could get back into the World Series against the Damn Yankees again.

“I can remember in ’51 when Bobby Thomson hit that home run off Ralph Branca to win the pennant. We had a TV. I was watching the game. I remember watching a dejected Billy Cox turn and walk hunched over toward centerfield, ’cause the clubhouse was in centerfield. Billy knew it was all over. No point hanging around.

“That was heartbreaking, because Cox indirectly was responsible. You say, If only certain things had happened. In the middle of the season the Dodgers were twelve games ahead of the Giants. How does a team close a gap like that? But they did. The Giants got hot and won enough to force a playoff.

“But in the middle of the season there was a game against the Giants, and Cox was on third base, and another Dodger hit a long drive out to the outfield, which should have scored him easily, but Willie Mays caught the ball and threw Cox out at home. No one could believe it, because Cox was fast. Cox assumed he could cool-breeze it home, and he didn’t make it. And because of that play, the Giants won that game. Had Cox kicked it into gear and scored, that ’51 playoff never would have happened. IF. The biggest word in the English language.

“We finally won a World Series from the Yankees in 1955. It was another shoot-out at the OK Corral. The people of Brooklyn were so yearning to win a World Series against these Yankees. We listened to each game on the radio. No one went anywhere unless they had a radio connected to them, in their hand or in the car or in their ear at the beach or on a bus. No matter where you were, you could walk down the street and hear the game out windows or cars roaring by. You could hear Red Barber or Vince Scully doing the play-by-play. Everybody was so attuned to it. Each game came and went, and the Dodgers hung on, and in the seventh game this kid Podres, this new guy, was really an unknown factor. He was a young ballplayer.

“We were winning the game late by the score of 2-0. We thought we were in good shape, that we had a shot. And with runners on first and second, Yogila [Yogi Berra] came up. We called him Yogila. Yogila, that number 8, and he swung at a ridiculous pitch, as he always did, and he hit a ball down the left field line, and we thought, There is no way this ball is going to be caught. It’s going to drop in and score runners, and there goes another one. But streaking across the outfield was this guy Sandy Amoros, number 15. He was left-handed, so he wore his glove on his right hand, which helped him catch the ball, because he streaked into the corner, stuck his right hand out, and good Lord, he caught the ball. He turned, wheeled, and fired the ball back to the infield, we got a double play, and that stemmed the rally and was the death knell for the Yankees.

“Horns began blowing along the Belt Parkway. Cars were going down the service road and along Emmons Avenue with their headlights on, horns blowing, cheering, carrying on. Sheepshead Bay was relatively quiet, but I know in other areas of Brooklyn it was all-out lunacy.

“Beating the Yankees was an absolute high, one of those moments in life when you look forward to something, after every year you meet with disappointment after disappointment, and finally you achieve this thing that is so important to you. When you’re eleven years old and this happens, it is unbelievable, as if you had hit the lottery. Nothing better could have happened.

“We won the pennant again in 1956, but there was a lot of talk of Walter O’Malley wanting a new ballpark. O’Malley seemed to think Ebbets Field was poorly situated. He said because the neighborhood was changing from white to black, people were reluctant to go there and attendance was falling, though I don’t believe that. O’Malley was seeing the likelihood of this eventually becoming the case. Only O’Malley knows his motives, and God only knows, but he wanted a bigger stadium with more seats. The bottom line is always the dollar sign.

“When we heard the Dodgers might leave, you thought, Where there’s smoke, there’s fire, but you hoped it would be resolved. Surely the Dodgers would never leave Brooklyn.

“Then it was announced in August of 1957 that the Dodgers were going to Los Angeles. Gil Hodges made the last out at Ebbets Field. And that was it. That was the end of an era. The Dodgers were gone, and not only that, but Roy Campanella got himself creamed in his station wagon on his way home in Long Island, and he broke his neck and turned into a paraplegic. That was very sad, heartbreaking. He never played in Los Angeles.

“In the spring of ’58 life in Brooklyn was dismal without the Dodgers. There just was no electricity in the air. The Dodgers became a tough subject. It was an unpleasant topic. Some people were angry, and others hung on, were still Dodgers fans, but generally speaking, the thrill was gone.

“One weekend in 1971 I decided I was going to play detective and look up Billy Cox. I was a New York City cop, and all I had was an envelope with a return address on it that I had gotten from Cox on a Christmas card back in 1953. It had a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, address. A friend of mine and his wife, and me and my wife got into my friend’s brand-new Thunderbird, and off we went to Harrisburg. We found the address, and it was in the middle of a black ghetto. I thought, No way Cox lives here. It’s been twenty years. How do I find this guy?

“I rode around the neighborhood and came upon a fire station. There were a couple of old white men sitting in wooden chairs, leaning back, chewing the rug with one another. I pulled the T-bird into the fire station driveway. I walked up and said, ‘I’m looking for a fellow who used to live in this neighborhood. Billy Cox.’

“They said they didn’t know any Billy Cox.

“I said, ‘He used to play third base for the Dodgers.’

“‘Oh,’ one of them said, ‘you mean Bill Cox. I don’t know where he is. I heard he moved up to Newport’—which was twenty miles north of Harrisburg—‘but I do know where his sister Daisy lives.’ She lived around the corner.

“I went to a row house, knocked on the front door, and inside I could see a Baltimore Orioles game on the television and a woman ironing brassieres.

“I told her who I was and who I was looking for and why.

“‘Come in,’ she said. ‘Want a beer?’

“‘No thanks,’ I said.

“She said, ‘Today is Sunday, so he’s tending bar at the Loyal Order of the Owls in Newport.’ She gave me directions.

“It was a red-hot day, a hundred degrees. We got there, and my friend and I knocked on the first of two doors like speakeasys had. Our wives had to stay behind in the car. Men only. We couldn’t get in because the county was dry on Sunday, and the only way you can drink is if you belong to a private club, and in Newport, Pennsylvania, the only private club in the town was the Royal Order of the Owls.

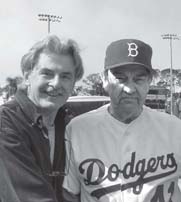

John Mackie and Clem Labine.

Courtesy of John Mackie

“A member finally came by, and when they opened the door for him, I was able to tell the guy at the door what I wanted. He let me in. Inside, Billy Cox was standing at a pinball machine. The balls were banging, and the machine was ding, ding, dinging, and here was a short, balding man with a big potbelly. He wasn’t that lean, thin fella anymore.

“I walked over to the machine, and I said, ‘I don’t know if you remember, but back in the ’50s when you were with Brooklyn, there was a kid who started a friendship with you because he wanted to play third base for the Brooklyn Dodgers just like Billy Cox. You sent him Christmas cards, autographed balls, and got him into the park.’

“He turned and looked at me, in the face and up and down, and he said, ‘You look pretty healthy now, Larry.’

“Larry was my name when I was five. I was born John Lawrence Mackie, but my mother wanted me to be called Larry. I couldn’t stand the name Larry, and when I was twelve I started calling myself John.

“Billy said, ‘I have to go to the bar. I start working in five minutes. You guys got time to stick around?’

“Our wives went to the local hotel in Newport and got themselves established. We sat there at the bar, and Billy got me blown out of my shoes. We sat and talked to him and his cousin Gummy, who used to travel with Billy on the road with the Dodgers.

“We had a great reunion. Cox was a very reticent man and a strange guy, but he treated my friend and me like royalty that day. A number of years later I read that Billy Cox had died of cancer.”