WHEN ROCK AND ROLL BROKE ACROSS AMERICA IN THE mid-1950s, white parents were aghast. Part of the outrage was a concern—no, a fear—that rock-and-rollers like Jerry Lee Lewis, Eddie Cochrane, and Elvis Presley were inciting their sons and especially their fresh-faced daughters to become looser sexually. The parents may not have known it, but the term “rock and roll” for years had been a slang black term for the sex act. The teen generation was ready to get it on.

There was an even bigger fear racing across pre–Civil Rights Act white America among the adults of the Dwight Eisenhower generation: “race” music. Racists were furious that glib and popular white disc jockeys like Alan “Moondog” Freed, Murray the K, and Bruce Morrow were disregarding society’s unwritten code by allowing black acts like the Moonglows, the Crows, Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, Laverne Baker, Ray Charles, and the dangerous Chuck Berry, among others, to poison America’s airwaves over the radio with their sensuous, exciting sound.

These disc jockeys—true, though rarely recognized, civil rights pioneers—were outraged that white artists like Pat Boone could cover (and tone down) a song by a more talented, black artist like Fats Domino or Ivory Joe Hunter and far outsell him, and they were determined to do something about the perceived injustice. They were also convinced that black music was what swayed the audience, moved the audience most, that the best rock-and-roll recordings were coming directly from the rhythm and blues and gospel sounds of the black community. And so, as often as they could, these DJs played these black artists over the airwaves. And when these black acts began appearing on TV with Dick Clark on American Bandstand, and black children danced together on the same floor with whites as millions of teenagers at home looked on in envy, one could argue convincingly that, like Jackie Robinson playing with the Dodgers, performers like Domino, Diddley, Charles, Baker, and Berry, and the black groups of the day—the Moonglows, the Charms, the Crows—along with Clark and the radio DJs who played their music, helped break down racial barriers and make America less intolerant and prejudiced.

With Dick Clark. Courtesy of Bruce Morrow

Freed, a Jew, was the true pioneer. He despaired of the way black artists were ignored by the white media, and though under threats of being fired, he deliberately, defiantly kept exposing America to these black artists, first in Cleveland and then in the biggest market of all, New York City. In both places his station kept attracting more and more listeners until the owners finally had to admit: “He’s making us a lot of money. Let’s leave him alone.” Murray “the K” Kaufman and Bruce Morrow also were instrumental this way.

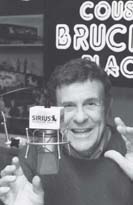

Of the three groundbreaking disc jockeys, only the Brooklyn-born-and-bred Morrow survives. In fact, fifty years since Bruce Meyerowitz from James Madison High School burst upon the scene as a young radio personality on WINS in New York, he is still going strong as a featured performer for Sirius satellite radio. Cousin Brucie was an important part of the lives of several generations of metropolitan New York listeners. Teens may not have seen eye to eye with their parents, but they always had a sympathetic cousin they could turn to in the evening. And he never failed us. We owe him a lot.

BRUCE MORROW “I tell people on the air I was born in Lubbock, Texas, but that’s only my dream, because I loved Buddy Holly. I was actually born in Flatbush, Brooklyn. I’m a 100 percent Brooklyn kid.”

He was born Bruce Meyerowitz on October 13, 1935. He never knew his father’s parents. He thinks they came from Russia. His mom’s parents were Austrian immigrants named Platzman.

BRUCE MORROW “My grandmother said they were not happy over there. They wanted to find the streets paved with gold. They wanted to get themselves a new opportunity in life.”

Meyerowitz’s father designed and manufactured children’s clothing. He called his company The Shop, employing forty workers. The firm designed hats and coats and manufactured them for other designers.

Though Jewish, the Meyerowitzes weren’t very religious.

BRUCE MORROW “They had an awareness of Judaism, but didn’t really follow the faith. I was brought up to be very free in my thinking, and I really thank them for that. It really opened my vistas quite a bit, not being stuck in the past—which is okay if that’s what you want, but I preferred—and I brought up my children the same way—to be free, to be proud of my heritage but not to be stuck to the rules.

“My parents were like that too, very open, never prejudiced. We were never taught that somebody’s skin color or religion made them inferior. I was brought up by my parents to believe in good and evil. If somebody did evil, he was a bad guy. But I try to believe there is good in everybody, and I still believe that to this day. I look for the good in people.”

Meyerowitz grew up in Flatbush on East 26th Street between Avenues V and W. The neighborhood was Jewish, Irish, and Italian. The kids had territorial wars, he said, but they were not fought because of religion.

BRUCE MORROW “We had what I call the Lot Wars. A lot was an empty field, and in Brooklyn in those days we had lots of lots. Our parents used to pack us off in the morning, give us an old Hellman’s mayonnaise jar filled with water, a wax paper–wrapped sandwich—peanut butter and jelly or cream cheese and jelly and white bread—trying to kill us, I guess—and a couple of chocolate cookies my mother baked but always burned on the bottom, and they’d say, ‘Go.’ Nobody had any fears anything would happen. The worst was we’d come home bleeding a little, but that was after playing a game of war. We’d hurl dirt bombs at each other, the 26th Street guys on one side, the 29th Street guys on the other. A dirt bomb would hit the ground and explode and throw dirt in your eyes, and they’d come and tag you.

“On the block itself we’d play ring-a-levio. I was a three-sewer man in punchball. That’s 150 feet. We’d play king and stoopball. The street became our entire theater. It was the arena.

“I used to go to Saltzman’s soda shop, which was right near my school, PS 206 on Gravesend Neck Road and East 21st Street. My favorite theater was the Mayfair on Avenue U and Coney Island Avenue, because it was walkable. We used to go there and stop in the deli, have a couple of hot dogs and a knish. We’d blow 25¢ doing that and another 25¢ to get into the movies, and for 5¢ we’d buy Good & Plentys so we could throw them at the matron. She was the disciplinarian, and when she’d walk up and down the aisle with her flashlight, as soon as she got past us, generally we threw the black ones and the pink ones at her, trying to hit her in the head, and we’d eat the white ones.

“As a child I grew up wanting to become a doctor. All my life I wanted to study gynecology. But my childhood was also deeply affected by the radio.

“I can remember a day in April in 1945. I was ten years old. I left PS 206 and walked the few blocks along the park near Bedford Avenue and Avenue V to my home. I had to be home by three thirty, so we had a little time to goof off, to go to the park or to Saltzman’s, to flirt, play around, tease the girls.

“My mother usually had milk and cookies for me when I got home. On this day I saw my mother on the porch across the street with Mrs. Flick and Mrs. Bloom and a few of these other very strong Brooklyn women, and they looked very upset. I got closer, and I saw them listening to a radio that was in the window, with the windows open. It was warm, and they were listening, and they were crying.

“I got very scared. My mother was crying, and these strong women who I knew were bawling hysterically. I was used to listening to the radio—ours was a little Bakelite box that said Philco on it—once in a while. It was magic, but I never realized it was informational, that it could have such an effect on humanity. Out of the radio came, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States Franklin Roosevelt passed into eternity this morning.’

“And I couldn’t understand why my mother wasn’t home getting my milk and cookies ready. Or getting dinner ready. What could have been so important? But from that day on I became extremely interested in that little black box, that magic box called radio. It’s my first recollection of wanting to get into that box.

“Like all kids, I would hide behind the console and make believe I was on the radio. I used to announce. I would take a newspaper or comic book, and I loved to do different voices. Friends would come in, and sometimes they would sing or play an instrument, and we would make believe we were doing radio shows.

“PS 206 went from kindergarten through eighth grade, and we went right from there to high school. The makeup was mixed: black kids, Jewish kids, and Italian kids. Very few Asians, and now it’s 60 percent Asian in that area. It was a terrific school, because it was a real mixture of different ethnic and religious people, which I think is an essential asset to growing up. Putting a kid in a school with the same background economically, educationally, religiously is cheating the kids. And it’s cheating the parents too.

“This was a great time in our lives. Nobody was afraid. Nobody was bringing guns to school. Nobody feared for their kids not coming home. Nobody had to worry about anything. It made growing up so pleasurable, so relaxed. It was easy, and you were able to develop skills. You didn’t have to worry about anything else. My friends were mixed, and nobody fought. You’d be together, play the Lot Wars, touch football, but you weren’t abusing or hurting anybody else.

“We were brought up to respect people. I was very lucky to be brought up in Brooklyn at that time, ’cause Brooklyn is very different today.”

He was first encouraged to use his oratory powers by PS 206 English teacher Elizabeth Frielisher.

BRUCE MORROW “You have to understand, I was very shy in class. I used to dread being called on. I wasn’t a brilliant student. I did my work, but I didn’t want to stand up in class. But Mrs. Frielisher made me read a poem in front of a microphone, and it sounded pretty good. And then I started doing announcements in school. That was my start.

“We used to have hygiene plays at PS 206. In those days we weren’t allowed to have sex education, because no one was allowed to use the word S-E-X. So it was called hygiene. In those days hygiene meant we learned how to wash under our arms, change our underwear, and brush our teeth. So we were really being prepared for the world. That’s why my generation is so screwed up. All we knew how to do was change our underwear and brush our teeth.

“There was an audition for the hygiene play to be shown in the auditorium, so I auditioned, and surprisingly to me, I passed, and I became an ugly tooth with a big cavity. I sang a song about how my mommy never told me to brush my teeth. And when I got out on stage, something happened to my body. I came out, and it was like somebody turned up the brightness. I was on that stage, and I was liking it. The inner me came out.

“When I was in the eighth grade, Mrs. Frielisher submitted me to the All-City Radio Workshop. It was a group of young people with instructors, professionals, which met at Brooklyn Tech High School that houses the studio and transmitter of WNYE-FM. Instead of taking regular English classes, we took courses in broadcasting. I did this for three years. I had my own radio show, and by the time I went to high school, I was feeling like a pretty big hot shot.”

After graduating from PS 206, Meyerowitz went to James Madison High School on Bedford Avenue between Quentin Road and Avenue P. By that time his father had made some serious money in the clothing business, and he moved his family into an upper-class neighborhood on East 29th Street between Quentin Road and Avenue P. Madison High was only a few blocks away.

When he got to high school, the kids knew him from hearing him on the radio, and his classmates asked him to perform in the Class Sing. Gone was his shyness about appearing in public. He played Goobah the Caveman and sang a parody of “Kisses Sweeter than Wine” by Jimmy Rogers. He was a big hit, and his class won the Sing.

It was in high school that he changed his name from Meyerowitz to Morrow.

BRUCE MORROW “In those days you couldn’t have an ethnic or religious name. You couldn’t be Italian or Jewish. You could be Irish. Irish was a common denominator. So I had to get rid of the name Meyerowitz.

“I was going out with a young woman named Paula, who lived all the way up in the Fort Tryon Park area. Paula and I were going to the Drama Workshop. I was learning how to dance.

“One night I was up at Paula’s house. Paula was extremely talented, and her mother was a kind of pushy stage mom. Her mother said to me that night, ‘If you’re going on the stage you can’t have the name Bruce Meyerowitz. Let me pick you a name.’ I said, ‘Sure. But it has to start with the letter M.’ I don’t remember why. Some kind of Jewish tradition? I don’t know.

“She pulled out the Manhattan phone book. She flipped through it and said, ‘Tell me when to stop.’ I said, ‘Stop.’ My name could have ended up being McGillicuddy or Morony or McCarthy. She put her finger down, went to the left and down and said, ‘Morrow. That’s it. Bruce Morrow.’ And that’s how I got my name.”

Morrow graduated from high school in 1953 and attended Brooklyn College for six months. He didn’t want to go, but his parents enticed him with a new Ford convertible if he’d enroll. Six months later, after skipping more classes than not, he dropped out. For the next six months he bummed around town with his friends.

A friend then told him that New York University was talking about starting a radio station but didn’t know how to begin.

BRUCE MORROW “I knew radio was going to be my life’s work. I went and interviewed for Professor Irving Falk. Right away he took a liking to me, saw something in me. He saw I was a go-getter, and for the first two years of my college career I built the radio station at New York University. It was as though they were waiting for me to come. They needed a student who had Brooklyn balls. I got the money to start it. I strung the wires outside the windows.

“Let me tell you about Brooklyn. Brooklyn gives you a backbone, and when you show somebody from Brooklyn an opening, a light, and the person believes it’s the right way to go, get out of his or her way. Nothing can stop them. They have a tremendous spirit. Brooklyn gives you a tremendous spirit. I am so proud of it, I can’t tell you. And I know I am as successful as I am today because of growing up in Brooklyn.

“I called the dean of the school. He never did give me an appointment, and I got fed up, so I walked into his office. It was snowing and wet out, and I was wearing galoshes, and I trudged sludge onto his brand-new carpet. He freaked. He looked up at me with eyes the size of silver dollars and said, ‘What do you want?’

“I said, ‘My name is Bruce Morrow, and I’m here to get some money so I can build a radio station.’

“He said, ‘You got it. Get out.’ He was furious with me. He gave me $28, and with that money I bought wire and speakers and a little Dynavox phonograph. I put it all together. I put speakers in the lounges all over NYU with the cable I bought, I strung all the wire, and we were on the air. We had a radio station. It aired in all the dorms and lounges at NYU.”

Morrow was at NYU when the rock-and-roll revolution broke over the country. Like teenagers everywhere, to him the popular music of the day—“Old Cape Cod,” “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window,” “Wayward Wind”—was just a bunch of tired acts. When Bill Haley & His Comets sang “Rock Around the Clock,” a new day in pop music had dawned. Morrow listened closely as the music for his generation began to change.

BRUCE MORROW “On the radio in those days was a gentleman by the name of Martin Block. He hosted a show called Make Believe Ballroom, and on Saturday morning he had The Hit Parade. As ’54 and ’55 came around, little by little something called rock and roll started to be heard. Rhythm and blues and vocal harmony started creeping in along with Perry Como and Patti Page and the Crewcuts, which to me was ad nauseam. ’Cause it was bland, monotone, boring, nothing new, but it was very safe. It was our parents’ music. That music only lasted a decade, thank God. By the way, even though it was my parents’ music, I know every single lyric of every single song. I know all the Perry Como songs. ‘Hot diggety, dog diggety, oh what you do to me…’ Little by little rock and roll started sneaking in. You heard Bill Haley & His Comets, then Elvis Presley came around, and we heard harmony, what they call doo-wop, which combined gospel, rhythm and blues, soul, and a little rock and roll.

“And suddenly black music, what we knew as ‘race music’ in those days—a disgrace on this nation of ours—I’m talking 1953, 1954, when the black records would be kept in a certain area of the store. And it was Perry Como and Pat Boone who covered the black artists, and they were the ones who got the air play. This was a very interesting time. Things were starting to change.

“I would go to the record store and buy records. I loved records. I bought the black artists like Bo Diddley. I realized that this was where the real music was. The Chords did ‘Sh-Boom,’ not the Crewcuts, though the Crewcuts outsold them twenty to one. I went to the store and bought the Gladiolas, and I found Laverne Baker and Ivory Joe Hunter, people like that, and I realized then that their music was being suppressed. I couldn’t understand why. It was a matter of finance and money, and then suddenly the record industry, especially the independents, found out there was a market for black musicians, and they started exposing it, and little by little they got some air play.

“By the time I got on the radio, it was no longer called ‘race music.’ It was being integrated perfectly in the play. Because when Alan Freed started his radio career in Cleveland as Moondog, they were trying to stop him from playing all this black music. They didn’t think there was any market for it.

“As a youngster I didn’t realize this was an issue, but by 1955, 1956 I knew. And our parents were frightened when they heard Elvis Presley and then saw him. It was like the devil’s doing. According to the parents, if you watched or listened to him, you would grow hair on your hand. Our religious, education, and political leaders took advantage of this, and they had themselves something to scream about, to yell on the pulpit about, which was absolutely ridiculous. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, some of these religious leaders were abusing little kids.

“In ’57 Jerry Lee Lewis came out with ‘Great Balls of Fire’ and ‘Whole Lotta Shaking Going On,’ great stuff, and by then Alan Freed had come to New York. They give him credit for coining the phrase ‘rock and roll,’ but I think that is not true. Alan Freed borrowed the phrase, because ‘rock and roll’ is an old black slang expression for the sex act. You can go back to the ’30s to find that. But Freed adopted it.

“Chuck Berry sang about rock and roll. There were great performers, and music helped heal a lot of the racial tensions in this land of ours, because suddenly we were listening to records by black artists, and soloists, and realizing, Hey they are just like we are. Whites who listened to them and liked their music became less racist.

“For years black groups like the Ink Spots and the Mills Brothers had huge white audiences, but they weren’t allowed to sleep in the same hotels as whites. This happened in the early 1950s to people like Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry. They would come into town to entertain, and they had to sleep in black hotels. Very sad. So rock and roll, I really believe, had a lot to do with racial healing. That’s been my thesis all my life.”

When Morrow graduated from NYU in 1957, he sent out demo tapes. Even though he had never been far from home in Flatbush, he knew he wanted to work in a warm climate, and he sent the tapes to Florida, Arizona, and Bermuda.

BRUCE MORROW “It was kind of scary. I had never left the nest, my Brooklyn. I didn’t know what lay ahead. I was so protected, I didn’t know there were some ugly things in this world.

“I sent out ten demos. Eight general managers said, ‘Go into your father’s business.’ One guy called me from Panama City and wanted to hire me. I called my father, and he picked up the phone. My dad was always at my side, and I miss him terribly.

“He said, ‘What’s the job?’ The man said, ‘He’ll work at the radio station, be on the air, sell some time four hours a day, and for the other four hours he’ll work in my other business.’ The pay was $75 a week. I had to start the next week. My father asked, ‘What’s the other business?’ The man said, ‘A car wash.’ We turned him down.

“Two days later I got a call from Bermuda, which was like the Magic Kingdom, millions of miles away, though it was really only ninety minutes by air off the coast of North Carolina. It was a foreign country, beautiful, an adventure for a young guy.

“I spent a year there, had the greatest time. Changed my life. Bermuda was settled by what they call the Forty Families. They left England to escape religious persecution. They were on the way to Virginia, and on the way their ship under the flag of Colonel Bermudiatis was shipwrecked on this twenty-mile-square reef. They got there, and they started practicing their own brand of persecution and religious dysfunction, though I have to stress that today things have changed. But this was 1958.

“Ken Bolton, the treasurer of radio station ZBM, took me around Hamilton, and I found a boardinghouse owned by a Mrs. McGuire. She loved me. Loved me. I started dating her daughter, and she was happy as heck about that.

“She was a lady who liked to drink, and one night she said to me, ‘One thing about Bermuda that is great. We don’t have any Jews here.’

“‘Mrs. McGuire,’ I said to her, ‘why do you say that?’

“She said, ‘You know how they are.’ The same bullshit.

“I had the nerve to say, ‘Mrs. McGuire. I’m Jewish.’

“She looked at me, drunk as a skunk, and said, ‘Oh, you’re not Jewish.’

“I said, ‘Why do you say that?’

“‘You don’t act or look like them.’

“Her daughter apologized, but I moved out. I never talked to her after that.

“I remember going to the movies, and blacks weren’t allowed to sit upstairs in the balcony. Orientals came from China, but Bermuda only let men in, not women. They were crazy.

“I used to do a show on the radio called Search Party. I used to have black kids and white kids dancing. It got to the point where I would get threatening phone calls that I better watch myself on the way home, that they were going to kill me.

“It was a ten-minute walk from the station to my home, and every time a palm tree would sway at night, I’d jump a million miles. I used to carry a lead pipe with me.

“I left Bermuda in an interesting way. A black church burned down, and they couldn’t raise the money to rebuild it, and nobody would help them. If you’re not Church of England in Bermuda, you’re dead.

“I held a big dance. I hired a big warehouse in Hamilton Harbor, and I threw a dance. I raised the money, and they rebuilt their church, and after that it was suggested that I leave. ’Cause they didn’t like that I was so friendly with black people.

“So I left Bermuda, but I learned about life there. In Bermuda they used to call me ‘the Hammer,’ because they never heard anyone talk like I did. See, I sounded like the music. I was very early with that. Alan Freed, who was my mentor, was the first one. He had that cacophony. He sounded like a rhythmic machine gun. Alan Freed used to pound on a big telephone book to the music. Rock and roll is a feeling, an emotion. You feel the music, a huge amount of energy. I still have that today.

“So it was time to go home, and I was getting tired. You don’t like getting threatened, and so I went back home to Flatbush, and I started looking for a job. I met somebody who helped me get a producer’s job at WINS. The DJs at WINS were on strike, and when the union pulls out the air staff, management walks in. Since I was hired as a producer, I was part of management. I wasn’t a scab. I wouldn’t have done that. When I was at NYU, WPAT in Paterson went on strike, and they came and offered me a job. I could have gone on the air, but I wouldn’t take it. I wouldn’t cross the picket line.

“I had all this airtime experience, so by the time the WINS strike was over, I had made quite an inroad, because I had my sound. I didn’t sound like the other executives. I sounded like I was having a good time. So they hired me as the staff announcer.”

Morrow joined one of the great lineups of radio history. Among his colleagues were Murray the K, Tom O’Brien, Jack Lacy, Stan Z. Burns, and Al “Jazzbeaux” Collins from the Purple Grotto. This was the heyday of Top Forty radio.

BRUCE MORROW “Top Forty radio started in the Midwest. A man named McClelland, who owned a radio station, took his program director to a bar every night, and they noticed that the customers were playing the same records on the jukebox over and over again. They started counting, and they counted forty different records, and that was the birth of Top Forty radio, as simple as that. People plunked their nickels into the same music over and over, and they kept score, and it became very obvious. And it spread all over the country.”

Bruce Morrow was making a name for himself at WINS, but he was looking for a handle, a name, that would stick in the minds of his listeners the way Alan Freed had called himself Moondog back in Cleveland, the way Murray Kaufman called himself Murray the K. Morrow found his handle quite by accident one night at work.

BRUCE MORROW “One night a security guard came into my studio. He said, ‘There’s a lady who would like to see you.’ I said, ‘Absolutely.’ He opened the door, and this white-haired lady, tiny in stature, walked in, and I motioned for her to sit down next to me. I said, ‘I’ll be with you in a moment.’

“I put a record on. I said, ‘What can I do for you?’

“She said to me, ‘Do you believe we’re all related?’ As soon as she said that, I thought, I’m going to get hit up for money. Because when I looked at her, I could see she wasn’t a rock-and-roll fan. And because I’m a Brooklyn kid, I know.

“I said, ‘Yes ma’am, I do believe we’re all related.’

“She said to me, ‘Well then, cousin, I’m broke. Can you lend me 50¢?’

“She had a sparkle and a beautiful smile, and I said, ‘Sure cousin, here’s 50¢.’ I was cheap. I should have given her a buck. I didn’t know all I was going to get out of those 50¢.

“She said, ‘Thank you, cousin,’ and she left.

“During the rest of the show I didn’t give it a thought, but that night, as I went home to Brooklyn, I was in the middle of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, and a light went on in my head. I repeated, ‘Cousin, lend me 50¢. Cousin. Cousin.’ And I said, ‘Jesus, that’s it. Cousin Brucie.’

“The next morning I called Mel Leeds, the program director. Don’t forget, I was very young, very low on the totem pole. I said, ‘Mel, I got my schtick. I want to be called “Cousin Brucie.”’

“He said, ‘That’s the corniest, stupidest thing I ever heard in my life. You think this is Morgantown, West Virginia? You think this is Cheesequake?’ He named tiny hamlets.

“He was glaring at me, but I felt he was testing me to see how sincere I was. I was a kid, but I garnered up all my energy, and I said, ‘Mr. Leeds, I’m a New Yorker, and you’re not. There’s nobody cornier than New Yorkers. Corny is like going to your cousin’s house and playing with his best toys’—because my cousins always had better toys than I had.

“He said, ‘Good point. I’ll tell you what you do. You try it tonight. But don’t overdo it. Because if you overdo it and you’re wrong, I’m going to fire your ass.’

“He scared the shit out of me. I went on the air. As Brooklyn Brucie, if someone says to me, ‘Try it,’ you don’t tell him to do it without going full-speed ahead. I don’t think a breath came out of my mouth that night without the word ‘cousin’ in the sentence. I cousined them, cousined the cousins.

“The next morning Mel Leeds called and ordered me to come to the office. He pretended he was going to fire me, and then he opened his desk drawer and showed me hundreds of telegrams. He said, ‘We’re putting you under a seven-year contract.’ Cousin Brucie was born.”

In the fifty years of Morrow’s career, the highlight came in 1964, when The Beatles came to America. By then popular music had become tired. It needed a shot of adrenaline. In England, groups devoured the likes of Chuck Berry, the Everly Brothers, and Jerry Lee Lewis, and began making their own sound. When in early 1964 the song “I Want to Hold Your Hand” hit it big on American radio, eyebrows went up. Who were these guys? When The Beatles arrived at Idlewild Airport on Pan Am flight 101, Bruce Morrow was there to witness the beginning of Beatlemania.

BRUCE MORROW “Let me tell you how crazy it got. They get to the airport. I’m stationed there with our news director to broadcast their arrival. The place was going wild, really controlled mayhem. A few hundred kids were on the tarmac, and thousands more were up on the roof. The police controlled it pretty well, but it was enough to allow for some good pictures and to start the hype. And believe me, Beatlemania was hyped. Because most of us geniuses thought it would last six months. And we also knew that radio had gotten very boring, and we could use something to continue the action. Little did we know The Beatles were going to change the entire face of the culture.

“They walked down off the plane, and they had their first press conference. A makeshift press area was put up in the Pan Am lounge, and the boys were very scared. They didn’t know what was going to happen here, even though they had had great success in Europe. This was the big time, the Big Apple, and they were in the United States where the streets were paved with diamonds. When they were looking down from the plane window onto the city, Paul McCartney said to John Lennon, ‘I don’t see any diamonds. Where are the diamonds you were telling me about?’

Cousin Brucie interviews the Beatles in 1964. Courtesy of Bruce Morrow

“Their timing couldn’t have been better. Their PR guy, Brian Epstein, would not bring them over here until they had a number one record in the States. ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ hit very quickly, so they were coming over as conquering heroes, the first of this onslaught of British groups that we knew about.

“So they were at this press conference, and they were very nervous, and if you remember that conference, they were very snippy. They were acting like wise guys. But they were scared, really scared, and the press was after them. You have to remember the press at that time—and they were inundated with press—really represented Mom and Dad. So the questions were pitchforks. ‘When are you going to cut your hair?’ That kind of garbage. The reporters didn’t understand the cultural importance of this group. Nobody really did. But once they arrived, we knew something was going on. It was crazy.

“And I was asked by Sid Bernstein, the promoter of the Beatles’ concert at Shea Stadium, to host the show with Ed Sullivan. Now, Ed Sullivan was the very first one to expose The Beatles on national television. And Ed Sullivan didn’t know The Beatles from salmon croquettes. Ed Sullivan didn’t know whether he was alive or not. He didn’t know if he was uptown or downtown.

“There’s a great story: Ed Sullivan called Walter Cronkite and asked him if he ever heard of this group in England called The Beatles. Walter said, ‘No.’ And then Walter said, ‘Wait a minute.’ And he called over to his daughter, who was sixteen, ‘Did you ever hear of The Beatles?’ And Ed could hear the kid screaming on the phone. The kid went crazy because she was listening to them on the Cousin Brucie show, and all the tabloids and teenage papers had spreads on them. So Walter said, ‘Ed, I’ll put my daughter on the phone. If you put them on your show, she gets two seats.’

“She was at that show and was prominently displayed in the audience. And that’s how Ed Sullivan found out who The Beatles were and booked them.

“Fifty million people watched that show that night, and I’ll tell you where I was: I was outside the theater. ABC asked me to cover this thing. The streets were full like New Year’s Eve on Broadway, and they piped out the sound. And the place was wild. I was outside, where it was exciting, because I was with the people that night.

“I was involved right from the beginning, playing the music and talking to them and doing interviews and having them on my shows. As a result, I was asked to introduce them at their Shea Stadium show.

“Shea Stadium was jammed. The feeling was there was going to be a disaster. I was in the dugout with them and Ed Sullivan, and John Lennon said to me, ‘Cousin, this looks very serious.’ I said, ‘It is.’ He said, ‘Can anything happen?’ I said, ‘No, don’t worry about it.’

“I don’t know if you’ve ever been in a crowd where you could feel its power. This crowd had this power. Con Ed could have turned off their generators, and the energy from the Shea Stadium crowd that day could have turned the dynamos. You felt it in your gut, your belly. It vibrated in your chest. The sound was amazing. You could feel the electricity, and the boys were very scared.

“Sullivan and I were to introduce The Beatles. I introduced Sullivan, and he and I introduced The Beatles. We walked up to the stage like it was a scaffold. Sullivan was in front of me, and he turned and said to me, ‘Cousin Brucie, this can be very dangerous, can’t it?’ I said, ‘Yes, Ed, very dangerous.’ He said, ‘What do we do?’ I said, ‘Pray.’ He turned back, and he very slowly walked onto the stage, scared stiff. I wasn’t exactly ready to dance the polka either. It was a frightening thing. I worried there would be an avalanche of people. There was such pent-up emotion, people could have been killed. Eighty percent of the audience was fifteen-, sixteen-year-old girls.

Cousin Brucie today.

Courtesy of Bruce Morrow

“Anyway, we introduced them, and the place went—I mean, forget it. I have never heard a sound like that in my life.

“Nobody heard their performance. You heard, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah’ once in a while and some percussion, but that was about it. They couldn’t hear themselves. It didn’t matter if they didn’t sing at all. They just had to move and play. But what they didn’t understand—none of us did—was that the kids weren’t there just to hear them sing. They have records. They have radio. They were there to share space. They wanted to be able to say they were with The Beatles live. That’s all that counted. It was a sociological event.

“While they were singing, the police commissioner came over to me with a couple of his men and asked if I would walk with them to help calm down the kids. There was chicken wire all over the place to keep back the crowds. They did everything they could to maintain order. I walked around, skirting the infield to the sides of the seats, talking to the kids. The cops showed terrific restraint. NYPD earned their badges that day. Because nobody got hurt. Nobody died. It was a phenomenal event. I have never experienced anything so electric, so dangerous, so exciting as I did with Beatlemania that evening at Shea Stadium.”