AT 8:37 P.M. ON THE SWELTERING NIGHT OF JULY 13, 1977, lightning struck an electrical substation on the Hudson River, tripping two circuit breakers in Westchester County. A second bolt hit the nuclear power plant at Indian Point. Two other major transmission lines became overloaded, and Con Edison was in deep trouble. After two more lightning strikes, by nine thirty the three power lines whose job it was to supplement the city’s power were overtaxed and in serious trouble. When Big Allis, the biggest generator in New York City, shut down, all the lights and energy of New York City went with it. Though Con Ed said the blackout was an act of God, Mayor Abe Beame, leading a city beset by financial woes, was scathing in his rebuke.

Air-conditioners went silent. Elevators stopped. Broadway went dark. Traffic lights went out. New Yorkers couldn’t watch TV, or listen to the news unless they had a battery-powered transistor radio. Those with flashlights or candles who owned books read. Many went on a looting rampage.

This was a whole lot different from what happened on November 9, 1965, when there was a blackout of the entire Northeast. Then, an area from New York all the way north to Canada lay in darkness. During the 1965 blackout, residents milled about outside their apartments on a cool fall evening, trying to enjoy themselves for the most part. This time it was scary different. In the twelve years that followed, the City of New York had nearly gone bankrupt. Unemployment was dangerously high.

John Lindsay had been a congressman from the Silk Stocking District of Manhattan, who had helped draft the 1964 Civil Rights Act. A liberal Republican, he all but disowned his party.

He was forty-three years old, handsome, had gone to Yale, served in the navy during World War II, and graduated from Yale Law School. He was elected to Congress from Manhattan’s Upper East Side in 1958.

In 1965 Lindsay won the election for mayor in an upset. It was expected he would restore pride to the city, but he turned out to be one of the more disastrous mayors in the city’s history. Hours after he was sworn in, the transit workers went on strike and were out for twelve days, shutting down the subway for the first time in history. His attempt at community control of the schools led to a bitter fight between black community leaders and Jewish teachers. For two months teachers went on work stoppages. When it was over, the alliance forged by blacks and Jews in New York had ended.

Lindsay won reelection anyway, some say riding on the coattails of the 1969 Mets’ unlikely World Series victory. During his second term, comptroller Abe Beame warned him that he was way over budget, but Lindsay could not bring himself to cut services. Instead, he borrowed. Bankruptcy loomed.

When his successor, the sixty-seven-year-old Beame, took office in January of 1974, Lindsay had left the city awash in $1.5 billion worth of debts. Beame, as Lindsay’s comptroller, knew what he was getting into, but he stoically took the job anyway. A year later Beame was forced by the banks to freeze all municipal hiring. Then he became a villain when he laid off a couple of thousand city workers, infuriating the unions. In April 1975, Standard and Poors suspended trading in the city’s bonds. In danger were city pensions, subsidized public transportation, rent-controlled apartments, and free higher education. Republican president Gerald Ford had no sympathy for the city. He refused to provide any federal aid. The headline in the New York Daily News read: FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.

Beame was in a box. During the summer of 1975 he had no choice but to fire 38,000 city workers, including 5,000 cops. New York’s Finest picketed. When sanitation workers walked off the job, the city began to smell. After Beame closed twenty-six firehouses, enraged citizens protested. Thirteen thousand public school teachers were fired. A graduate of City College, Abe Beame ignominiously ended free tuition at New York’s public colleges after 139 years.

Library branches and public hospitals closed. New York City was slowly dying.

After the firing of five thousand policemen, crime began to rise dramatically as the city became less and less able to deal with the growing social and economic problems of the poor. In the 1970s, arson became commonplace in poor neighborhoods, such as Bushwick, as landlords, unable to toss out deadbeat tenants, set the buildings on fire to collect the insurance. Some derogatorily called the practice “Jewish lightning.” Vandals also set fires for the fun of it. Entire blocks were burned, one building at a time. As they burned, crime rose. Drug dealing became commonplace.

This time, when a blackout occurred, looters and vandals struck thirty-one neighborhoods across the city, including every poor neighborhood in the five boroughs. Stores in Alphabet City—in the East Village—in Manhattan were looted. East Harlem was pillaged. So was the Upper West Side. The Bronx was hit hard too.

The most damage occurred in Brooklyn. Areas affected included Crown Heights, Sunset Park, Williamsburg, Brownsville, and Flatbush. More than seven hundred stores in Brooklyn were looted or damaged.

Bushwick was hit worst of all. Ten years earlier it had been a middle-class white community, but between 1973 and 1976 the city had lost 340,000 jobs, and white flight to the suburbs accelerated. Black middle-class families moved in, but jobs were hard to find, and when they left, Bushwick became inundated by welfare families, some who had been “temporarily” relocated from East New York and Brownsville as part of a Model Cities program. One problem: the new housing promised was never built.

In 1976 there was more criminal activity in Bushwick’s 83rd Precinct than in any other district in central Brooklyn. Meanwhile, racial tension was growing. Almost all the cops in the 83rd Precinct were white, and most of the residents Hispanic or black, although some Italians still lived along its western border.

On the night of July 13, 1977, Bushwick was populated by a lot of poor people who were angry and frustrated. Temperatures were still in the high nineties. Water levels were dangerously low.

Shortly after the lights went out that night, enveloping the entire city in darkness, the residents of Bushwick vented their anger as thousands, sensing the opportunity, rushed from their sweltering apartments toward the shops on Broadway. Because of the cutbacks, there were exactly thirty-four police officers on duty in an area of a hundred thousand residents. Off-duty policemen rushed to the scene, but without help from other precincts, the men of the 83rd were woefully outnumbered.

When New York’s second blackout occurred in July 1977, many of Brooklyn’s black neighborhoods were decimated by looting. Bushwick was particularly hard-hit. AP Photo

Professional criminals sawed off locks or used crowbars to open steel shutters. They stole tow trucks, then used the tow hooks to pull off storefront gates. Next came the shattering of glass followed by the wholesale looting of jewelry, electronics, and furniture stores. After the professional criminals struck first, alienated adolescents and those motivated by “abject greed” followed in profusion. When many store owners heard about the looting, they rushed back to their stores toting guns—most always too late. When the cops didn’t arrive on time to prevent looters from taking guns and ammo from John and Al’s, a sporting goods store, the situation became even more dangerous.

That night not one single cop from another precinct was sent to help the members of the 83rd.

After the expensive shops and the shoe stores were emptied, the looters next set their sights on the grocery stores and bodegas. After five hours, there was little left to steal. What came next was the burning of Bushwick. Two blocks of Broadway were on fire at one point. When firemen came to put out the fires, residents threw rocks, bottles, and other objects at them.

When dawn timidly arrived, broken glass, mannequin parts, litter, and soot-blackened water covered the area. By the morning, thirty blocks of Broadway were damaged or destroyed, forty-five stores had been looted and torched. More than twenty fires still burned the next morning.

In all, 1,600 stores in New York City were looted or damaged and 3,776 people arrested, the largest mass arrest in the city’s history.

Despite the estimated $300 million dollars in losses, Jimmy Carter, who had run for president on a platform of promising to help New York, refused to declare the city a disaster area, using the excuse that it was not a natural disaster. As a result, the city was denied federal funds. Mayor Beame, whose endorsement of Carter helped him win the election, was bitter. Carter never even made a token visit. The looting gave whites more ammunition to hate and fear blacks.

The power didn’t come back on until 10:39 P.M. the next day.

Abram Hall was living in Bushwick at the time. The night of the blackout of 1977, he says, accelerated the downward spiral from which Bushwick is still trying to recover.

Abram’s father. Courtesy of Abram Hall

ABRAM HALL “I was born on March 10, 1962, in St. Mary’s Hospital in Brownsville. My daddy was from Riegelwood, North Carolina, which was originally called Carver’s Creek, and then it got a little bit more segregated, so they changed the part where the blacks lived to Riegelwood. My daddy died when I was only three years old. Everything I know about him was told to me by my mother and her brother and sisters.

“My daddy was a favorite son. He was the leader of the family in a lot of ways, after my grandfather, who was a bit of a patriarch. My grandfather had a farm. He started out with one wife and one bull, and he built it into a pretty big farm, and even though he had my dad and ten or twelve sisters, every one of them went to college, including my dad. He went to a community college on a basketball scholarship in 1945, and then he went into the army, and he was posted in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1945, and he stayed in Germany for five years. He didn’t want to come home, because North Carolina was so racist.

“Eventually my grandfather got him to come home. He went to the Red Cross and told them he hadn’t seen his boy in five years, and so they contacted the army and got him transferred back home. I didn’t think Daddy was too pleased about that.

“But I guess it worked out for the best because he got transferred back home, went to Washington, DC, and met my mother. She was from Rockfish, Virginia. If you watched The Waltons on TV, that’s where the show took place. Rockfish is a real place in Nelson County, Virginia. My mother knew Earl Hamner [author of the novel Spencer’s Mountain, which became the basis for The Waltons] when they grew up. He lived on one side of the road, and she lived on the other. The thing is, back in the 1940s, there was only one high school, and only white people were allowed to go. My grandmother wanted my mother and her sisters to get an education, so she sent my mother to stay with her sister in Washington, DC. My aunt had a boardinghouse, and my mother stayed with her while she got a degree from a technical high school not far from Howard University.

Abram’s mother, Daisy Hall.

Courtesy of Abram Hall

“My mother became a Washington Senators fan, while my dad became a Brooklyn Dodgers fan, because my uncle still tells me all the people down there in North Carolina all became Dodger fans when Jackie Robinson joined the team. To this day most of my dad’s family will root for National League teams. My aunt Ernestine, who lived in Brooklyn before retiring down there, will always root for the Dodgers, unless they are playing the Mets.

“Most of my relatives from my dad’s side of the family came to New York because that’s where the jobs were. My mom and daddy came to Brooklyn in 1957. They came to Brooklyn because it was more affordable than Manhattan and less racist than Queens. I’m not saying it wasn’t racist. It was less racist. My aunt Ernestine and my aunt Waddy owned a house in Brownsville about two blocks off Eastern Parkway, and by the mid-1960s things had gotten so bad she moved out to Springfield Gardens, where they burned a cross on her lawn. But their attitude was, ‘We’re staying,’ and they did. But you had to be careful.

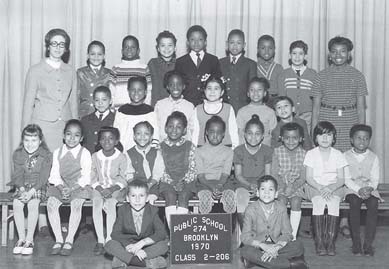

Abram’s second-grade class photo shows the changing demographics of Bushwick. Courtesy of Abram Hall

“My parents first moved to Patchin Avenue in Bed-Stuy. I went to PS 274, the Kosciuszko School. It’s on Bushwick Avenue, one block from Broadway, which served as a dividing line between Bedford-Stuyvesant and Bushwick. We eventually moved into a three-family house on Himrod Street in Bushwick. That’s where I grew up.

“Bushwick was originally settled by the Dutch. And starting around Cooper Street, we had breweries, Rheingold, Shaeffer, and when we were kids we’d go on tours. Some of the large houses in Bushwick had been owned by the brewery owners.

“I went to Amsterdam a few years ago, and the construction and architecture of those houses were exactly the same as the one we were living in. We lived in what they call a railroad flat. You go in and walk straight through all the way to the back. We had a pretty backyard.

“We rented the third floor from a Mrs. Sumter. She used to keep a lot of foster kids. One of them, a guy named Gene, had a little dog, maybe two feet long, named Sputnik. He was the friendliest dog, but he would kill sparrows and rats, and my little sister Patricia was afraid of him.

“When I was growing up it was one of the most beautiful neighborhoods in Brooklyn. There were pretty tree-lined streets, a true bedroom community. Bushwick Avenue was closed to commercial traffic. Bushwick had been predominantly working-class German, Dutch, Italian, and some Irish, and we were the first black family to move in. Next door we had this one girl, Rose Marie, a little bit older than me, but younger than my sister Rita. Her grandmother loved me. She gave me candy and comic books. But I discovered as I got older and began to understand things that a lot of the people weren’t so pleased to see us. My mother was deeply involved in the Bushwick Neighborhood Council, the block association—in a different lifetime she would have been a politician. Ma was a compulsive joiner. She explained to me later that after Daddy had died she needed to keep busy.

“There came a time when more and more white families moved out and more and more black and Puerto Rican families moved in. Our church, which was on the corner of Bushwick Avenue and Himrod Street, started out as a predominantly white church, and then as years went by more and more of them left, and it became more and more a predominantly black church.

“It became more dangerous. We didn’t lock our doors during the day until 1970 or so. Hard crimes started coming in. Hard drugs started coming. And then in July of 1977 we had a blackout.

“I remember it so clearly. I was fifteen in 1977, and I had a summer job at the church. I had returned home and night had fallen, and I was sitting in my sister Rita’s room looking out onto the street and listening to WCBS radio. I was reading The Once and Future King when the lights went out.

“My mother was worried because Rita was going to New York City Tech, which is in downtown Brooklyn. Mrs. Sumter was going to pick her up, but something was wrong with her car, and she couldn’t go. There wasn’t much she could have done, because the traffic lights were out, and there was no way to get down there really.

“And as time went on, this went from, ‘Oh wow, this is fun,’ to where you started saying, ‘Hmmm, there’s something wrong here.’ It was eerie. You started hearing noises. That’s what I remember most, the sounds, the noise. It was no longer pleasant. Something had gone wrong.

“People were running up and down the streets with bags and boxes, and you heard the sounds of windows being broken. At a certain point you didn’t want to be outside, because this was bad. You heard the noises, and you could see the police cars racing up and down Bushwick Avenue. Around eleven, I could see these guys in a station wagon with all this stuff like box springs and mattresses strapped to the top of their car pulling a tight turn with the cops chasing after them, and the cops pulled them over, and they had a spotlight on their car, and the guys were resisting and they had guns. A lot of people started screaming and yelling. Some people threw something at the cops, and this one cop swung around, and he had his gun out, and he said, ‘If you don’t get back in your fucking houses right now…’ My older sister pulled me down from the window.

“The rest of the night we heard things. I heard someone who was walking down Broadway saying, ‘They’ve wrecked Broadway.’

“Broadway was our shopping center. It was a strip that went all the way from Jamaica Avenue to the Williamsburg Bridge. If we had to, we’d go down to Fulton Street and go to A&S or May’s or Korvettes. But Broadway was our main shopping center. As the night went on, I could hear the vandalism. Looting was going on in the stores, and police were fighting with the looters.

“The next morning it was like a storm had passed. Finally I went out to take a walk on Broadway, and it was horrible, nothing but the crunching and tinkling of broken glass. Broadway had been destroyed. Lakin’s Department Store was wrecked. The supermarkets had been ransacked. All the little shops too. My mother had bought a guitar from a music shop, and the store was destroyed. A toy store. The Sunset Shop. It was as though a bomb had hit them.

“To this day I don’t get why there was so much vandalism. I suppose at the beginning it was, ‘Ha ha ha, freebies.’ And then it took on a life of its own, when the professional criminals came in. But Bushwick was in transition, and right after that a lot of arson hit Bushwick, people collecting insurance money. I also heard from one of the elders of my church, a white woman, essentially my godmother, she worked in a bank on Gates Avenue, and she told me point-blank, ‘I’ll never forgive the SOB in the 81st Precinct.’ That was the precinct on the other side of the J train. She said when the looting started, the captain of the 83rd Precinct, in Bushwick, begged the captain of the 81st Precinct to give him some of his men, and the captain of the 81st Precinct refused to give them to him. How was it that Knickerbocker Avenue, which was predominantly white, was protected, and how come our area of commerce was just destroyed? If you do the math, you know the answer. And after that night, our neighborhood was never the same again. The blackout of 1977 was the dividing line. There was no going back after that. That was it. After that I felt danger walking out my front door. Not every minute of the day, not every day, but it was there often enough. Drugs began to take over, and street crime rose. I had to deal with bullies. I had to deal with people trying to rob me. Mrs. Sumter’s mother was mugged I don’t know how many times. She was an old woman. Houses were always being broken into. Cars were being stolen. I wondered, How bad can it get? Pretty bad.

“I didn’t move until after my mother died in 1986. She died the day before her birthday, of a heart attack. My mother had been a teacher for a while, but she developed a heart condition, and she had to retire. Before she died, she was telling me about how she was getting strange phone calls. She’d pick up the phone, and the person at the other end of the line would hang up.

“She died on a Saturday, and her sisters came over and stayed with me. The strange phone calls continued. We went out to the funeral home on Utica Avenue on Tuesday to make arrangements for the funeral. My cousin gave my aunts a lift, and on the way home there was a traffic jam, and they got out to walk the last block, and they surprised guys who were robbing our house. I’m glad I didn’t see them. They had smashed down the door, and when my sisters walked in on them, they ran across the roof. They had stolen pretty much everything of value, except for a few things they didn’t have time to pack up. And I was furious, because my mother was dead, and they had stolen the last Christmas gift my mother had given me.

“Even after the robbery, the strange phone calls continued. Rita said, ‘They’re calling to see if anyone’s home so they can break in again.’ On the day of the funeral I left my uncle Bert to watch the house. He’d been a commander in Vietnam, and he and a couple of his lodge brothers kept watch. They did try to break in, and he apologized to me that he didn’t catch them, but I’m glad he didn’t. I was afraid of what might have happened.

“But after the funeral my sisters said, ‘You have to leave.’ I didn’t want to go. I didn’t want to leave my house. But they said, ‘People are calling at strange times. They’re breaking in. How can you stay?’ So I moved to Manhattan to live with my sister Rita. I lived there for two years. Then I moved back to Brooklyn.”

Abram Hall today in front of his old house at 48 Himrod Street.

Courtesy of Abram Hall