Demolition of the Thunderbolt, 2000. It last operated in 1983.

Library of Congress

RICHARD PORTELLO WAS BORN IN BAY RIDGE HOSPITAL SIX months before the assassination of President Kennedy. His great-grandparents had come to Brooklyn in the 1880s from Italy and settled in Brooklyn. The family congregated in a one-block area by Avenue T and West 9th Street.

His relatives, born of immigrants, were hardworking, productive members of society. His dad’s father worked for the A&P supermarket chain, testing olives. After he was laid off, he worked for the R. J. Reynolds tobacco company. His grandmother did beadwork on wedding dresses. His mom’s dad drove a truck.

Portello’s father spent most of his life as a butcher. The shop had been around the corner from their home, and Portello’s father began working there as a youngster, making pennies a day. As he grew up, he was taught how to cut meat, and it became a career.

Portello, who was born in 1963, grew up in Bensonhurst on West 5th Street between Avenue O and 65th Street. He was raised Catholic. No meat was served on Friday nights. The Portellos usually ate pizza or some kind of macaroni. At two P.M. sharp, Sunday afternoons, the whole Portello clan gathered for dinner.

Tony’s, a candy store, sat on one corner. To this day, says Portello, he has never tasted better malteds or egg creams. The movie theater he attended most frequently was The Marboro on Bay Parkway. It’s where he saw Jaws and where he experienced his first kiss. [The theater was demolished in 2007.]

When Portello was in his early teens, his mother, not wanting to go alone, would wake him up in the middle of the night and drive the fifteen minutes to Nathan’s in Coney Island for a hot dog.

“She would just be in a mood,” he says. “Then when I was in my late teens and early twenties, every Sunday night during the summer my friends and I would go to Coney Island and ride the Cyclone and the Jumbo Jet.”

From first through eighth grade Portello went to St. Athanasius Catholic School on Bay Parkway between 61st and 62nd streets. From there he went to William E. Grady Vocational High School, a vocational-technical school specializing in air-conditioning and TV repair as well as the automotive, electrical, and printing trades.

Richard Portello with his grandmother on the day he was promoted to lieutenant. Courtesy of Richard Portello

As a kid, Portello lived down the street from the corner firehouse. He spent a great deal of his time there with the men, and for years he swore that when he grew up, he was going to be a fireman. Then he entered high school, took climate control, and when he graduated in 1981, he began a career repairing and maintaining oil burners.

Unhappy with the way his life was going, when he heard from a friend about an upcoming fire department test, Portello decided to apply.

First came a written test. There were math questions. If a hose length is fifty feet and you need to drag the hose three hundred feet, how many lengths of hose do you need?

There were questions asking in which direction a gear turns. There was a memory section, where the applicant was shown a picture, and he had to remember what he saw.

Forty thousand men and women took the test. Twenty-seven thousand made it to the second round. Portello was one of them. He scored a ninety-eight.

Next came the physical test, which was designed to separate those who would be hired from the thousands rejected. An applicant needed to get a hundred in order to get hired.

The test was strenuous. First you had to pick up a length of hose and run with it fifty feet. Then, with another length of hose, you had to run up a flight of stairs and run to a window, and then drag the length of hose into that window. You then had a hundred seconds to walk from one side of the armory building to the other, then you had just over two minutes to jump over a six-foot wall, pick up a twenty-foot ladder lying on the ground, stand it up, climb it to a platform, run back down, pick up a 15-pound dumbbell, go up three more flights of stairs, pick up an 80-pound tire, carry it twenty feet across a table, crawl through a twenty-foot tunnel two feet high by two feet wide, then carry a 180-pound dummy around the twenty-foot table.

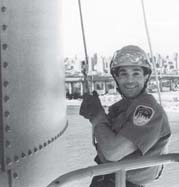

In training for a high angle rope rescue, Portello repels from a 360-degree tower. Courtesy of Richard Portello

To prepare, Portello paid to take a review course. After the course, he figured the test would be a piece of cake, but just to be sure, he decided to take a second practice course, this one run by an FDNY lieutenant by the name of Pudgy Walsh. It was a good thing he did. After being put through his paces by Walsh, Portello discovered just how difficult the test was going to be. He practiced hard, and when it was time to perform for real, he made a perfect score.

Twenty of his buddies had taken the test with him. Of the group, Portello was the only one to score a hundred and get hired.

“It was probably the happiest day of my life,” says Portello. As for the others? “Everybody else became cops.”

Portello’s first assignment was to Ladder 118 in Brooklyn Heights.

RICHARD PORTELLO “Here’s how the fire department works: there are engine companies, ladder companies, squad companies, and rescue companies. Our 118 was a ladder company. We had one of only fourteen ladder trucks left in the city, which you still drive the front and the back.

“In a [ladder or] truck company, basically what happens, there are five positions: when you get to the fire, the ladder company forces entry into the building, the men look for the fire, they find the fire, they search for people, and they vent windows.

“Then the engine company stretches the hose and actually puts out the fire. It may not look like it, but there is a very particular order in which things are done. For instance, one of the jobs of the truck company is to go up to the roof of the building, and that guy will open up and vent the roof so the heat and smoke has someplace to go.

“First he will open up anything he can, and if the fire is on the top floor, he will cut the roof with a saw. Then what happens, the engine company pulls up, and sometimes there’s just a lot of smoke. The men on the truck have to go in and locate the fire. Once they do, they let the engine men know, ‘It’s third down on your right.’ The engine team will stretch the hose, go to the third room on the right, and once they have water, are ready to put out the fire, and are ready to move in; there’s a man from the truck team outside the building who will break the window and give a place for the smoke and heat to go. It’s very orchestrated.”

Portello served with Ladder 118 for three years, in the end given the important job of vent man. He then transferred to Engine 214 in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

RICHARD PORTELLO “There were quite a few more fires there than my first company, and I got a chance to work with some of the guys who were in the fire department from what we call ‘the heyday.’ Those guys were on the job in the 1960s and 1970s during the blackout and the riots. I was fortunate to get to work with those guys. They had so much experience. And as long as you were interested and asked questions, they were very good about sharing their experiences.

“They told quite a few stories. The night of the [1977] blackout they would be putting out one fire and look up the block and see another fire, and they’d have to leave the first fire and go to that one, and there’d be two more fires burning on the next block.

“The same with the riots. They told of a Brooklyn dispatcher asking on the department radio if there were any companies available in Brooklyn. There weren’t.

“Firefighting is very much a team effort. Any time you see a fireman being interviewed after a rescue, you will always hear him say, ‘It was a team effort. Everyone did a great job. I just happened to be the one.’ And truly we depend on each other. That’s what makes the job so great: the camaraderie and the fact we would do anything for each other, and we would do anything we could for anyone trapped in a fire. You just keep going until the fire is out and you get everybody out.”

Portello wanted to return to a truck company, and in 1991, just as the citywide crack epidemic was winding down, he transferred to Ladder 103 in East New York.

RICHARD PORTELLO “It was pretty incredible to me, the devastation of the neighborhood from the crack epidemic. When I got to 103, we were the only building on an entire square city block. The only building. Everything else was weeds.

“In the late ’50s and early ’60s there were apartment houses on the block—tenements, we called them—but they all burned down during the heyday, and then it was all vacant lots except for the firehouse. It was pretty amazing. I went there recently, and all the buildings have been rebuilt. Wow, what a difference!

“But when I arrived there, East New York, like Bed-Stuy, was very busy. There were a lot of fires during the seven years I was there.”

In 1997 Portello was promoted to lieutenant, and he got the job of “covering,” working at night and bouncing from company to company as needed. By September of 2001 Portello was assigned to Squad 41 in the South Bronx.

RICHARD PORTELLO “Squad 41 is part of Special Operations Command. There are only seven squads in the entire city. A squad at a fire has a pretty big response area. Squad 41 covers all of the South Bronx and Manhattan. We cover from 80th Street on the East Side and 100th Street on the West Side all the way up to the northern end of Manhattan.

“A squad can be used as an engine or as a ladder, depending on what the chief needs. We are manpower. We find out how the chief wants to use us when we arrive at the scene.

“We are veterans, and in addition to the fires, we respond to hazardous material incidents. We respond to subway derailments, car accidents when people are trapped, confined-space rescues, and building collapses.”

On September 11, 2001, Squad 41 responded to the greatest building collapse in history, the toppling of the twin towers of the World Trade Center after each was attacked by Al Qaeda terrorists who flew jetliners into the buildings. After the towers fell, trapping thousands under the debris, the body count began. Of the 2,752 men and women who died in New York on 9/11, 343 firemen lost their lives, including 12 from Squad 41. Years later, 9/11 remained a topic that Portillo found just as painful to discuss as though it had happened yesterday.

They say that timing is everything, and on that beautiful sunny morning in September, Richard Portello wasn’t at his post. He was home in Staten Island.

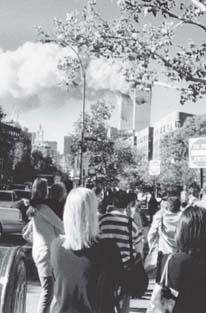

The Twin Towers on fire on 9/11, looking south on Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village. Doug Grad

RICHARD PORTELLO “I wasn’t working that day. In the squad it was change of tours, and everyone met to be given positions by the officer. Then after the first plane hit, they were relocated to Manhattan to cover Squad 18’s area, after Squad 18 was sent to the Trade Center. Then after the second plane hit, Squad 41 also was sent to the Trade Center.

“So I was home and had gotten dressed to go when somebody called me to say a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center. I was going to drive, but then I said to myself, ‘Who am I kidding? If I get on the Gowanus Parkway, I’m going to be stuck in traffic like being in a parking lot.’

“I was watching on TV to see what was going on, and then the second plane hit, and then I knew it was terrorism, and I got in my car to head in. By then the Verrazano Bridge was closed, so I went to Rescue 5, the firehouse on Staten Island, and a bunch of us went to the Staten Island ferry and got across on the ferry.

“By the time we got on the ferry, the first building had collapsed and the second one was still on fire. When we were halfway across to Manhattan, the second one came down.

“It was incredible to look at. I stood there, not believing what I was seeing. We landed in Manhattan, and there were thousands of people at the ferry terminal looking to leave Manhattan. There was a city bus there, and we all got on it, and we had the bus take us to the site.

“There was a division chief on the ferry boat going to Manhattan, and he assigned five firemen to a lieutenant or captain, and we wrote down on a piece of paper what we call a ‘riding list.’ What happens normally, the officer keeps a copy on him, and a copy goes on the fire truck with everyone who is riding that day. The chief made us fill out a ‘riding list,’ and he took one copy, and each officer kept a copy. Once we got to the Trade Center, we went wherever we were needed or wherever we felt we could do some good.

“As we were walking up to the site, there was this white stuff all over the place. It almost looked like snow. It was very quiet. I was assuming the white stuff muffled a lot of noise. It was very, very quiet. All you heard was the occasional voice of someone you were walking with. White stuff covered everything. Lower Manhattan was pretty empty by then.

“We got up to the site, and it was total devastation. We just went to wherever we thought there were voids, and we searched the voids to see if we could find people. All six guys from Squad 41 were missing, five firemen and a lieutenant. And this was true of companies all over the city. There were roughly four hundred men in Special Operations Command, and we lost ninety-three.

“I was there until one in the morning. We realized it was fifteen hours after the fact, and we needed to let the families know they were missing and that we were looking for them, to tell them to say your prayers and let them know we were doing everything we could.

“I notified the wife of one of the men, and I went home for two hours, and then I went right back to the site. I spent weeks there. I can’t tell you how many.

“It was a very difficult experience, but you know what? We looked at it as our job, and we also knew it wasn’t nearly as difficult as what those guys did that day. So we just wanted to find as many people as we could, both civilians and firemen. And hopefully give their families closure. And in between spending all that time at the site, I went to a lot of funerals, as many as I could. It had a psychological effect on me—it did on everyone, including civilians. As time went on, I spoke to a lot of New Yorkers, and I would hear their stories.”

Squad Co. 1, after a fire. Portello is fourth from left.

Courtesy of Richard Portello

One result of the death of so many firefighters was that there were openings in the hierarchy. The Sunday after Tuesday’s World Trade Center attack, Richard Portello was told he was being promoted to captain and that he would head Squad 1 in Park Slope, starting in late January. When he finally reported, he saw that the squad, which had lost twelve men in the disaster, including their captain, James Amato, was well on its way to being rebuilt.

RICHARD PORTELLO “The guys were doing a tremendous job. They didn’t need me to get them going. We started bringing in some new men, and the old guys did a great job teaching the new guys. And the new guys learned quickly. Everybody did an incredible job. It was a total team effort. We all worked hard, with the common goal of rebuilding the company. It was very important, because twelve guys got killed, and we were all determined to bring the place back to what those guys had worked so hard to build.”

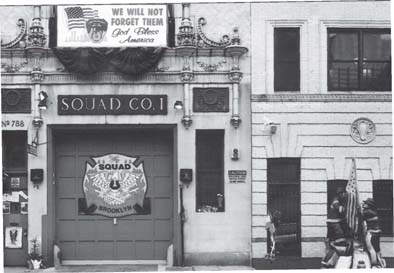

The front of Squad Co. 1. The 9/11 memorial is to the right. Courtesy of Richard Portello

To the right of the firehouse sits a wooden memorial to the men from Squad 1 who lost their lives on 9/11. Like the soldiers at Iwo Jima, the sculpture depicts firemen hoisting an American flag amid the rubble of the fallen towers. According to Captain Portello, it was donated by an artist from Oregon and placed on the site owned by the Park Slope Food Co-op next door. On the wall of the Squad 1 firehouse the names of the men who fell on 9/11 are listed: Captain James Amato, Brian Bilcher, Gary Box, Thomas Butler, Peter Carroll, Robert Cordice, Lieutenant Edward D’Atri, Lieutenant Michael Esposito, David Fontana, Matthew Garvey, Lieutenant Michael Russo, and Stephen Siller.

RICHARD PORTELLO “When you go to a fire you depend on each other so much. This, and every other firehouse in the city is very tight. The camaraderie is amazing, and that’s every firehouse in the city.”