AT THE TENDER AGE OF TWENTY-THREE, JANET BRAUN-REINITZ already had made history when, in the fall of 1961, this well-to-do suburbanite from Rye, New York, rode a Greyhound bus from St. Louis into the heart of the racist South to test the Jim Crow practices as one of the “freedom riders.” The first stop was Little Rock, and the bus was met by hundreds of screaming whites. After arrival, she and four others went to the waiting room of the bus station, where she was arrested and taken to the city jail. Unprepared, she was terrified. It was the lead story on the Huntley-Brinkley Report.

After spending three days in jail, the freedom riders were told they would get suspended sentences if they’d leave Little Rock. After two stops in Texas, the bus moved on to Shreveport, Louisiana, where a large gathering of angry whites and police awaited them. To avoid trouble, they left town at two in the morning. At their last stop, New Orleans, she and a black civil rights protester were served at the lunch counter. Reinitz would say later that her civil rights activity was inspired by the coming of Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers.

Upon her return to New York, her husband was accepted to graduate school at the University of Rochester. She would have to take her civil rights work with her.

Braun-Reinitz joined the Rochester CORE chapter and immediately became involved in the case of Rufus Fairwell, an attendant at a gas station. On August 23, 1962, he was closing up when the police pulled up. Sure that he was robbing the place, the police arrested him; he wound up in a wheelchair, with two cracked vertebrae and a severely damaged eye. Back in the 1960s, blacks got shot by the police all the time, and nothing ever happened. This time it was different. The civil rights movement was slowly building.

Her husband died in 1979, and in 1987, after her children were off to college, Braun-Reinitz moved to Park Slope. A mural painter, she was able to pursue her craft on a grand scale. Her work can be seen all over Brooklyn, especially in East New York.

On September 7, 2001, she moved from Park Slope to Clinton Hill, between Fort Greene and Bed-Stuy, across the street from Pratt University.

Four days later she was a tad late for an early-morning meeting at 7 World Trade Center. After watching the second plane hit a tower and explode in an orange ball, she decided it would be best to get off Manhattan island. She walked across the Brooklyn Bridge as the cloud of debris from the fallen towers rose behind her.

If she was horrified by the events of the day, she was even more upset by the actions of President George W. Bush, as she waited in vain for him to rush to New York to show New Yorkers he cared. Several days later, when the president finally did arrive, he promised money to help repair the damage and ease the pain, but his promises would prove to be empty. Then came his invasion of Iraq in 2003, a sovereign country with seemingly little or no connection to the Al Qaeda terrorists who brought down the towers. After Bush’s administration spent countless billions mounting an unpopular war, the Republican Party had the nerve to hold their 2004 National Convention in New York. Braun-Reinitz once again marched in protest.

JANET BRAUN-REINITZ “After Rufus Fairwell was gunned down by the Rochester police, I felt very strongly that we had to do something about this, and so we had a meeting at our house, and all sorts of people came: ministers, a rabbi, a really good group of people, and we talked well into the night about what we were going to do. The people who came from the university were full of verbiage and analysis, but no action. Finally at two in the morning, I said, ‘I’m sick of this. I don’t know what the rest of you are going to do, but I’m going to sit in at the police station.’ One of the black schoolteachers said, ‘I’m coming with you.’ No one else volunteered.

“The wife of one of my husband’s fellow graduate students said, ‘I’ll stay out here and do the PR. I’ll call UPI and AP and I’ll check on you about seven in the morning.’ She did a great job, because by nine in the morning there were a hundred people sitting in at the police station.

“What we were asking for was a police review board. Meanwhile, Malcolm X was scheduled to arrive in town to speak at the university. He was also going to be speaking at a settlement house in front of a black audience. We went. There were six white faces in the audience, and he was mesmerizing. To watch him was an experience unlike anything I had ever had. Malcolm was smart. He was powerful, and he scared the hell out of me, because he talked about the blond-haired, blue-eyed devils. And there I was: brown eyes, brown hair, but it was the same deal.

“When Malcolm spoke at the University of Rochester, it was a different kind of speech, much more intellectual and controlled, and afterward he and CORE got together for a meeting on the campus. He had bodyguards. There were about twelve of us there, and Malcolm laid it out. He said, ‘Right now these people’—the city—‘think you’re the radicals. And they are not going to give you the right time of day. But if they perceive that we have joined the fight, we will be perceived as the radicals, and you will be just where you need to be, which is right in the middle ground.’

“Malcolm X spoke out about the Rufus Fairwell case, and it all worked. Rochester became the second city in the United States after Philadelphia to have a civilian review board. And Fairwell sued the city and won, a victory though the man was still in a wheelchair. How often did a black victim get compensated? Never. But we won through that very simple tactic and timing—Malcolm made his statements at a crucial moment, and I am forever in his debt in a thousand different ways.

“I also met Martin Luther King. I chatted with him a little bit. I met him through a mutual friend, a black woman who was hounded by the FBI for being active in the movement.

“Our phones were tapped. We knew that, because we could hear it. These days the FBI has all sorts of people they are after—terrorists, environmentalists, critics—so I don’t suppose anyone would bother to tap my phone, but just in case, HELLO, HOW ARE YOU? But it was like that.

“I am permanently paranoid. I rarely use a credit card. I don’t book my own flights. I don’t have e-mail. I’m not kidding. After my husband died in 1979, I wanted to get his FBI file. I had a lawyer write to get both of our files. His came back describing his having stowed away to get to Europe when he was seventeen, which he did, but everything else was blacked out because he had been in the Young Socialists League. They said they had no record of me and could I please give them some information so they could find it. My lawyer wrote me a letter. It said, ‘I don’t know what they’re after, but I suggest you drop it immediately.’ Which I did.

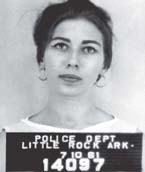

Janet Braun’s mugshot.

Courtesy of Janet Braun-Reinitz

“For a while I used to cross the street so as not to walk past a policeman. I finally got over that, but I am of that paranoid generation. I told my daughter, ‘You won’t find me on Google.’ She said, ‘Mom, there are fourteen pages on you on Google.’ That’s where they found my mug shot from my booking in Little Rock. I had never seen it. I looked pretty good. The kids had the photo put on a mug. Hilarious.

“Everybody has had a moment—it’s not possible now not to understand at a very early age, even if you’re white and privileged, that the world is segregated and that people are discriminating against you. But you could live that way without understanding it.

“I got involved in the women’s movement. I got involved in the antiwar movement, though I must say that I always felt that the antiwar people were extremely disorganized. When they were tear-gassed, they would go, ‘Oh my God, we’re being tear-gassed.’ I kept thinking, Doesn’t anyone train anyone? Don’t they know? Why aren’t they disciplined? It always made me angry when people whined when they got tear-gassed and were taken off to jail.

“After my husband graduated, he taught at Hobart and William Smith in upstate New York. After he died, I promised my children I would stay in Ithaca until the last one graduated from high school. We had brought them to Brooklyn in 1974, when my husband swapped jobs with a friend of his, and so we lived in the city for a year. But my kids were small-town kids, and they were not happy. And when the last one graduated, I came to Brooklyn, and I began painting murals. I had been to Nicaragua. I had been to Georgia in the former Soviet Union, painting murals. I had painted one in Ithaca. And I had really gotten the bug to take my art to the streets and work for a mass audience. What I liked most in life was to be out on a scaffold on the street.

“I moved to Fifth Avenue in Park Slope [in 1987], an old Italian neighborhood as well as a black and Latino neighborhood. It wasn’t long before it would become the most elite place in Brooklyn, but it wasn’t then.

“I lived over a butcher shop. The building was owned by the butcher. There weren’t many restaurants or bars, no movie theaters, but there were good things, like cobblers. When the cobbler goes, the neighborhood is gone, as far as I’m concerned. At that point there were no Starbucks. It had a great flea market. Not much else was there, but it was close to Prospect Park, and it was pretty, not too noisy, and affordable.

“Then about five years later, about 1992, the change came. My building got sold, and the new owner, an Italian, was planning on putting in one of the first chic restaurants in Park Slope. He really wanted to put his workers in the building. Meanwhile, a homeless man moved onto our roof, and at some point I wasn’t happy anymore.

“I hooked up with another artist, Rochelle Shicoff, and we rented a great, big, walk-through apartment, still in Park Slope. Each of us had our own studio and bedroom and our own sitting room. We shared the kitchen and the bathroom.

“She’s a great person, and we have collaborated on painting murals. During this time I hooked up with the United Community Center, a community organizing group in East New York. Mel Grizer, the director, understood the power of murals for community organizing, and for the last ten years I have been out there during the summer, painting murals. This has been my living.

“The very first mural I did, at 999 Blake Avenue in Brooklyn, was a baseball mural. In 1988 I was asked to go out to East New York—I knew nothing of East New York—but I went out and looked at the wall in an industrial park, a very rough place. I designed a 150-foot mural called Home Run that wrapped around the corner of the building. It’s all silhouette of someone at the plate hitting a home run. On the other side of the wall is a dugout, and there’s a crowd in which I painted all my favorite baseball players. I’m a Mets fan, so Doc Gooden was pitching, Darryl Strawberry was hitting the home run. Mookie Wilson was on base. Keith Hernandez was at first, and Ozzie Smith was at shortstop. In the dugout was Henry Aaron, and then there was this huge baseball about four feet high on the wall where the baseball was autographed by Jackie Robinson, Stan Musial, and a lot of players. When people came and wanted to do graffiti, they would write their name on the baseball. The workers would come out of the factories at lunchtime while I painted, and there would be a discussion of baseball during lunch hour. It was wonderful.

“Home Run,” corner of Hinsdale and Glenmore, East New York, Brooklyn. Courtesy of Janet Braun-Reinitz

“Then I met the people at the United Community Centers, and I did about ten murals for them. The United Community Centers was started around the idea that working-class people should be able to live together in an integrated and positive way. By the time I got there, East New York was the murder capital of the city. But UCC had gotten a building and ran a day-care center, and took up the issues that arose in the community. When private interests tried to put a sewage plant in East New York, the UCC hooked up with our assemblyman, Charles Barron, a young man with ambitions, and stopped it. The UCC has never sold out. As a result, it has been politically committed, not politically smart, and therefore very poor. But Mel Grizer understood that painting murals in a community is a sign that people care. Among the murals I’ve painted is one called From Somali, West Africa, to East New York, Brooklyn. We used traditional signs and symbols and invented others for the neighborhood, so that we have the symbol of the gun with the X through it and hot dogs and Brooklyn Bridge and headstones from old cemeteries.

“Another mural is the Woman’s Wall. It reflects the health issues of women in the community. Another painted in Martin Luther King Park is called Freedom Train and Interracial Journey. We paired Thurgood Marshall and Earl Warren. We paired Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey, Eleanor Roosevelt and Marion Anderson. Wilma Rudolph, Roberto Clemente, Maya Angelou, and Alvin Ailey, the dancer, are represented, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and Louis Armstrong.

“Last summer we did the biggest one yet, in Bed-Stuy, called When Women Pursue Justice. It’s seventy-six feet long and forty-six feet high and features ninety mostly twentieth-century women activists. Shirley Chisholm is there, of course. She stands four feet by six feet, along with Emma Goldman, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, Wilma Mankiller, Fanny Lou Hamer, Dorothy Day, and Margaret Sanger, who is controversial in the black community because she believed in eugenics. When the radical money ran out, she took a lot of money from the eugenicists, and the black community never forgave her, because she didn’t speak out against it. Ever.

“I moved from Park Slope to a little slice of Brooklyn called Clinton Hill. It’s between Fort Greene and Bed-Stuy. I moved in in September of 2001. I like Clinton Hill very much. We have a wonderful coffee shop, just not a chain. People do not sit there all day with their computers. You can go in any direction, and there are varieties of people, and it’s very nice, integrated by age, race, and by class, where Park Slope is white, upwardly mobile, double strollers and nannies. There are more nannies in Park Slope than other people. It’s supposed to be a liberal place, but it was, ‘You don’t want to build a halfway house in our neighborhood.’ Some things don’t change.

“Four days after I moved to Clinton Hill, I was headed to an all-day meeting at the Deutsche Bank building at the World Trade Center. I never go to that part of town, but it was an art meeting for an organization I work with in the public schools. It was primary day in New York, so I had stopped to vote, and I was late. I was supposed to be there at eight thirty in the morning, and I was a little late, and as I came out of the subway at Fulton Street, the first plane had already hit.

“When Women Pursue Justice.” Courtesy of Janet Braun-Reinitz

“I asked a cop what was going on, and he said they thought a private plane had hit the tower. There was a streak of orange across the building against this bright clear blue sky. I have to say—it sounds awful—that it was beautiful. I said to the cop, ‘I have to get to this meeting.’ He said, ‘Lady, you can’t go down there.’ I said, ‘I have to. I’m late.’ I paid no attention to the gravity of the situation. None. I started on my way anyway—until I saw the second plane hit the other building. They say there wasn’t a lot of noise or a lot of panic, but it depends on what you think noise is and what you think panic is. Because you could feel the noise bouncing off the buildings in those canyons. It was all around you and very personal. It sounded like explosions—all around, which you couldn’t see. And it kept reverberating.

“My instinct was to get off Manhattan island. I had a little radio with me, because I was going to be in this meeting all day, and it was September, and there were ballgames I had to know the scores of. I needed to know how the Mets were doing.

“The artists who had gotten there on time were held in that building, and they evacuated just at the time the towers collapsed. No one was hurt, but they were caught in the mess, and they suffered from a lot of posttraumatic stress and a lot of inhaling of nasty things.

“I ran as far as City Hall Park, and then I tried my cell phone, and it was dead, and I listened to my radio trying to figure out what was going on, but that didn’t work very well either. I decided the best thing for me to do was simply walk across the Brooklyn Bridge. It was open for traffic going out of Manhattan, and it was open for people walking out of Manhattan. Nothing was allowed in except for emergency vehicles.

“This was before the buildings had actually collapsed. I got onto the bridge, and I kept looking back, and I kept my radio on, and when I got about halfway, I could see a group of five or six guys running across the bridge, and my thought was, They know something I don’t know. This bridge is about to go. I felt, If it does, I’ve had a moderately long and interesting life, and it’ll be okay. I turned my back to the smoking towers, and I walked with some haste. By the time I got off this long, long ramp onto Tillary Street, I heard on the radio that a plane had attacked the Pentagon and a fourth plane had crashed. I have to say I didn’t quite understand the gravity. I had just moved to a new apartment, and I was very busy trying to figure out where I was and how I could get home.

“The scope of it didn’t really hit me until later in the day. Then I went and gave blood, which was what everybody did. The one thing I was waiting for was for Bush to come to New York. Rudy Giuliani, who was hardly my favorite mayor, was doing very well, coming on the television, saying, ‘I don’t have any answers, but it’s okay.’ You could see from where I live the cloud over Manhattan coming toward us. And I kept waiting for Bush to arrive.

After the World Trade Center fell on 9/11, the smoke blew right over Brooklyn, as seen from the Manhattan Bridge. Doug Grad

“If you remember the accident at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, Jimmy Carter, a nuclear engineer who knew how dangerous it was, came immediately. Unlike Carter, Bush didn’t come. And he didn’t come. And he didn’t come. And I had that feeling all over again that for him New Yorkers weren’t really Americans, so no one in the federal government was coming to take care of us. It was dreadful.

“Aside from what happened to the city, our government’s answer was not to take care of us but rather to go find a scapegoat and make war.

“During the run-up to the war, New Yorkers turned out by the hundreds of thousands to show they didn’t want war. It was clear to a lot of people that Bush intended this war no matter what anybody thought. It was very interesting being in Europe and hearing people talk about Bush. They don’t understand how Americans could have voted for him—twice.”

On Sunday, August 28, 2004, hundreds of thousands of protesters filled the streets of Manhattan to protest the presence of the Republican National Convention and the war in Iraq. As marchers passed Madison Square Garden, they would at times erupt into chants of “Liar, Liar.” Janet Braun-Reinitz and her son were among the marchers.

Janet and friends protesting the Bush agenda.

Courtesy of Janet Braun-Reinitz

JANET BRAUN-REINITZ “There were hundreds of organized events around the convention. If you were a woman and wanted to march against the Republican policy of choice, you could. If you wanted to go and march to protest what was going on in Darfur, you could. You could march with labor, march on immigration, march for peace.

“My son and I marched over the Brooklyn Bridge. In one demonstration we marched in front of the Fox television headquarters. We went to the Sudanese embassy to protest the genocide in Darfur. We marched up and down Fifth Avenue [in Manhattan].

“There were a huge number of people in the streets. The cops were cordoning us off. The usual stuff. At one point I said, ‘I know where we can go to rest. We can go down by Macy’s, where there’s a little park.’ But CNN had set up their outdoor interviewing headquarters there. When we got there, it became very dicey.

“One of the things about having been in the civil rights movement, you have a different antenna for crowds. We were two blocks from Madison Square Garden. I saw more police. The traffic was stopped. All the streets were cordoned off, and there were a lot of empty buses in anticipation of arrests.

“I just felt uncomfortable. I said to my son, ‘Let’s get out of here.’ We ducked into the subway, got in through the turnstiles, just before the police blocked all the entrances. We got on the train that was on the platform—I don’t remember if it was even going in our direction—but we got out of there.

“There were a lot of arrests. It wasn’t Bull Connor–ugly, but it was such an insult to see the Republicans in the city. They said the convention was going to help our economy, to show solidarity with us. When you think how antithetical they are to anything about this city, it was just one more slap in the face.

“Bush never did give us the money he said he was going to give us. And whatever facilities we have in this city, we pay for. We’re paying for it, and we have to do this because of the policies of Bush and the feds. If Bush had not waged war on our behalf, and that’s the point—on our behalf—we wouldn’t have as many potential terrorists. It seems so clear and sensible that what he has done is so irrational, and the fact it’s all being done in our name—it just rubs the wrong way every day—every time there’s something the city needs money for, something other than security. I get so angry. It’s not something I can be completely rational about.

“We New Yorkers know we really don’t have a place in Bush’s government. As far as going out in the streets to protest, the truth is, at this point we know it won’t make any difference in terms of federal policy. But it does make one feel better. I think there’s a little less hopelessness. It was so different for civil rights, where the targets of who we were going after were so clear. Here, to be anti-Republican is very amorphous. Primarily because we really haven’t a clue as to what’s really going on in Iraq. Plus the amount of money that disappeared to Halliburton—you would think that alone would cause Americans to vote them out.

“I was talking to Bob Filner, a freedom rider who is now a congressman from California. He told me when he first ran, his opponent questioned the validity of it—was he really a freedom rider? And he lost. The next time he ran he won.

“We’ve come to expect these Republican attacks. The Swiftboat campaign against John Kerry was another example. There was no outcry, because he wouldn’t stand up. That was surprising. But people are not going to protest for someone who won’t protest on his own behalf.

“We’ll see what they dig up this time.”