IN THE 1980S THE ECONOMIC MIRAGE OF THE REAGAN ADMINISTRATION changed everything, bringing in a pestilence of speculators, developers, and profiteers of all sorts. The empty apartments seemed to fill up overnight, and rents shot up. With rent control and rent stabilization cramping their profits, some of the less scrupulous landlords resorted to dirty tricks: threatening tenants, turning off heat and hot water during the winter, and disabling elevators in high-rises in order to get the tenants to move out so new, higher rent–paying tenants could move in. There were more landlord-tenant disputes and rent strikes than ever before.

Marty Markowitz grew up poor in Crown Heights. His father, Robert, who’d worked as a waiter in Sid’s, a kosher deli, died when Markowitz was nine. A couple years later his mom, Dorothy, moved into subsidized housing with Marty and his two sisters. Markowitz had to work, but that didn’t stop him from getting a college degree. He graduated from Brooklyn College in 1970 after taking night classes for eight long years. It was in 1971 that he decided to fight back against the tactics of the landlords. He organized the Flatbush Tenants Council, and it wasn’t long before his organization grew into what became Brooklyn Housing Services, the largest tenants’ association in New York and probably in the whole country. On a salary of just $10,000 a year he worked seven days a week fighting for Brooklynites who didn’t have the ways and means to defend themselves.

Markowitz became a public figure as a result of his championing tenants’ rights, and he turned to politics as a career. He served in the New York State Senate from 1979 until 2001—eleven consecutive terms—all the while living like a transient in a threadbare hotel room in Albany, returning as often as possible to his Brooklyn home. He held on to his seat even though his constituency went from being 55 percent white to 92 percent black and Latino after being jerrymandered twice.

Jill, Marty, and Sherry Markowitz. Courtesy of Marty Markowitz

While he was a state senator, Markowitz coveted the post of Brooklyn borough president, long held by Howard Golden. The popular Golden, who was elected to the job in 1978, had an iron grip on the position. Golden defeated Markowitz in 1985, and Golden would have kept the job indefinitely, until term limits made him bid adieu. Even though revisions to the city’s charter in 1990 stripped away the power from the borough president’s office by abolishing the Board of Estimate that controlled NYC’s purse strings, Markowitz quickly threw his hat in the ring. In 2001 he defeated Ken Fisher and was reelected in a landslide four years later.

After Markowitz became the borough president in 2001, he became the face of Brooklyn. He attended every parade, every opening, every festival, and issued proclamation after proclamation, all the while promoting his beloved turf like a modern-day P. T. Barnum. If there ever was a true public servant devoted to his hometown, Marty Markowitz is it. Tommy Lasorda always bragged that he bled Dodger Blue. Lasorda has nothing on Marty Markowitz. Especially since before the word “Dodger” comes the word “Brooklyn.”

Markowitz is also bound by term limits, and he is scheduled to depart in 2009. His final political decision looms: whether to run for mayor. Meanwhile, under his leadership, Brooklyn’s economy is booming and Brooklyn residents are feeling very good about themselves and their borough.

“Why not?” asks Markowitz. “Why would you want to live anywhere else?”

Young Marty rides a pony.

Courtesy of Marty Markowitz

MARTY MARKOWITZ “I was born on February 5, 1945, in Crown Heights. My grandparents came from Germany and Romania in 1915, and I lost them when I was very young. I was only eleven when the last of my grandparents passed, so I don’t have any recollection of them except that my grandfather on my mother’s side had very beautiful suits—he must have been very successful in his day. I also remember how he would pour coffee into his saucer and then drink it with a cube of sugar.

“My dad was a waiter in a kosher delicatessen on Empire Boulevard. I remember the pastrami and corned beef. He did that six days a week, and he worked another job six days a week as a shipping clerk for a company called Cardinal Place, which manufactured men’s clothing.

“My dad loved the Dodgers. If the Dodgers won, everyone in the deli seemed to eat more. If they lost, it was a sad day for him. I can remember the Dodgers as far back as 1950, when I was five. I went to the games with my father. He didn’t have that much time off, but when he did, he’d go to the games. We lived two blocks away from Ebbets Field, and we walked there. During batting practice my friends and I would hang out on Bedford Avenue, hoping Campanella or Snider would hit one over and we’d catch a ball, though I was never quick enough to get one. When I was around ten, my friend and I would sneak into Ebbets Field. We waited for the main crowd to come in, and maybe in the second inning nobody was there anymore, and other times the ticket-takers would hand us a ticket.

“I can remember one game when the Dodgers were leading the Milwaukee Braves twenty-four to three, and even though it was the eighth inning, nobody left the game. Absolutely nobody left. That’s how happy we were. And I can remember the Brooklyn Symphony and Hilda Chester and her cowbell.

“The day we won the World Series in 1955 was the most glorious day of all. Brooklyn stopped. A trolley that ran on electrical wires ran in front of the building I lived in, and I remember the passengers coming off screaming and yelling, and people were going crazy in the streets. I went down with some of my friends and watched the procession, which went around Borough Hall. People hugged and kissed and jumped up and down. Looking back, to me it seemed the celebration lasted for about a month. I’m sure it didn’t, but it sure seemed that way.

“To us, the Yankees were a Manhattan team, not a Bronx team. I know they were called the Bronx Bombers, but I looked upon them as being elitists from Manhattan. We were the workers, and they were the elites, the aristocracy.

“My favorite players were Duke Snider, a slugger, and Johnny Podres, who beat the Yankees in that final game in 1955. He was a great pitcher. And I loved Gil Hodges, and when I was young, Jackie Robinson certainly was my idol. He was all the kids’ idol, the most popular player on the team.

“I grew up in a liberal family, and the fact that he was able to play for Brooklyn was an exciting thing. Civil rights movement was beginning—not that my father was active, but there was that sense of civil rights and equal opportunity and stopping the bigotry, even in those days.

“Our joy, of course, was short-lived. The Dodgers left after the 1957 season, leaving us with shock and anger. I was twelve years old. I didn’t know about the role Robert Moses played in not letting the Dodgers build a new ballpark at the Atlantic Yards. But there is no doubt that O’Malley, as the owner of the Dodgers, was a dreaded name. There was shock and disbelief we would lose the Dodgers. It was unheard of, and after they left, we were filled with a great unhappiness, a terrible sadness. After the Dodgers left, of course we were hoping beyond hope that someone would come in and play at Ebbets Field. We wanted another team to come, but obviously that didn’t happen.

Carl Erskine with wrecking ball as the demolition of Ebbets Field begins. AP Photo

“Another sad day came when they knocked down Ebbets Field. I was there because I lived two blocks away, and I saw this big ball knock it down. As I’m talking to you, I can see the crane out in the outfield. I must tell you, on the fiftieth anniversary of our winning the World Series, I went to speak to Little Leagues, and when I told the kids, ‘The Brooklyn Dodgers defeated the other team from the Bronx,’ all I heard was, ‘Boo, boo, boo,’ because they were Yankee fans. They were raised as Yankee fans. I said, ‘God, forgive them. They know not what they do.’ And their parents laughed, and they laughed. Although the parents weren’t around either.

“I went to junior high school in East Flatbush, and then to Wingate High School in Crown Heights. I graduated from Wingate in 1962. I was always interested in politics. I remember when Dwight Eisenhower paid a visit to Brooklyn in 1956, we all went up to Empire Boulevard to see his motorcade. Martin Luther King was an idol of mine in the 1960s, when I became conscious and the country became conscious. I had worked in 1960 to help get John Kennedy elected president. I worked with the local Democratic committee.

“My first experience with civil rights came when I was fourteen. I was in a White Castle, which is still there on Empire Boulevard. At that time you would bring your car in, give your order, and a girl would bring it out. The kitchen staff was black, but the servers were white. Blacks could not serve you. And CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, called for a boycott. I was the only white guy on the line that I can remember. I’m sorry to say an Italian kid swore at me, put me down. So it was in middle school that I began to see images of what was happening in the South.

“Wingate High School was about 40 percent black. I didn’t have any problems. There was a lot of friction between the blacks and the Italians. There were rumbles, because part of Crown Heights was all Italian. The Jewish population picked up on Lefferts Avenue going north up the Eastern Parkway. Crown Heights was Italian, a rough section, and coming home I would have to watch myself. I don’t remember any racism or name-calling in the school itself. Blacks and whites did everything together.

“One of our basketball heroes was Roger Brown, one of the greatest basketball players of all time. [Brown was a small forward with the Indiana Pacers in 1967–75, leading the Pacers to ABA titles in 1970 and 1972. He died of liver cancer in 1997.] I used to hold his coat. I was proud to hold his coat. Oh yes, he was a star. And in the [New York City] finals at Madison Square Garden against Boys High, we lost by one point. Connie Hawkins was their star. There was no name-calling. None of that. Blacks obviously knew there was a significant amount of racism, even in Brooklyn, which was not integrated. It was difficult for blacks who wanted a cab ride, and they lived with poverty, and when blacks started moving into neighborhoods, people fled. Those days are gone. That doesn’t happen anymore.

Assemblyman Markowitz with Coretta Scott King.

Courtesy of Marty Markowitz

“We lived in Crown Heights, and after my dad died of a heart attack, my mom was up against it. She tried to get into public housing, but it took a number of years.

“My mother wrote letters to politicians, and they didn’t give her the time of day. But then she wrote to Jacob Javits, who was our senator, and he helped us get into the Sheepshead/Nostrand Houses. I lived in public housing for five years.

“It didn’t bother me. I was young. I didn’t know anything. Actually, it was a nice development. We had hot water and electricity and modest rent.

“I went to Brooklyn College at night starting in 1962, and during the day I’d work. I had to contribute to my family. My sisters were younger than me, and I had to take care of my mom.

“I had quite a few jobs. I worked at CIT as a commercial factor. It was the days before computers, and my job was reading tallies on commercial properties. I went from there to selling tobacco for May’s, a department store attracting lower-income customers, where my mom regularly shopped. I was a detail salesman for P. Lorillard, makers of Kent cigarettes. In those days I smoked. Everybody smoked. I would call on candy stores, trying to get them to take a couple cartons of cigarettes. I put up posters in windows. I gave out samples to customers coming into the stores. I did it because May’s gave me a company car, and I couldn’t afford my own car. It was a way of having a job and a car. But I didn’t know the car they gave their salesmen didn’t have a backseat. It was filled with cigarettes. Nonetheless, I appreciated having the car very much. But the job only lasted a year and a half. I couldn’t stand it. I gave up smoking in 1973.

“From there I went to Clairol. I called on variety stores and drugstores, selling their products, and then I left that and went into personnel placement, finding people jobs. I did that for a couple years. I was a kid. And then I got a job with a company that specialized in the placement of lawyers.

“I already knew I wanted to go into politics. By the time I was sixteen, I knew I wanted to be borough president. To me that was a bigger deal than Congress. Right after I graduated college in 1970, I took a job as head of the student government at the graduate level at Brooklyn College. And because of doing that, I didn’t have to work in Manhattan. I stayed in Brooklyn, which gave me access to the neighborhood where I lived. I no longer was living at home. I had moved to Flatbush and my first apartment on the short block of Tennis Court.

“In 1969 I became a member of the Democratic Club. I became really active in the club from my neighborhood. Mel Miller was the head of the club. He later became an assemblyman, and I became his campaign manager. My job was ringing doorbells for him, canvassing. It was at that same time in 1971 that I founded a group of tenants, to fight for better conditions in the building.

“Rent regulations kept rents very low for long-standing tenants, but rent regulations also made it almost impossible for a landlord to throw out a long-standing tenant. So the landlords would deteriorate the place to make him leave. Many landlords would bring blacks in, because they knew nothing worked like that did. And it worked. There was an extensive city program that gave the landlord a bounty if they placed a low-income black family. The landlord would get a $2,000 bonus per apartment, because there wasn’t enough housing for low-income people. So the landlords sometimes got a double dime. Not only did they get their bonus, but they got the long-standing tenant paying low rent out of the building. It worked. Needless to say, it’s a fact that it worked. They knew what they were doing. So there was that issue and also the issue of a diminution of the quality of service.

Assemblyman Markowitz speaking. To his right is Howard Golden, the borough president who preceded him. Courtesy of Marty Markowitz. Photo by Deborah Gardner

“Even though I had a job, I helped the tenants organize, and I spent most of my life fighting for tenants’ rights—because I was involved in politics. My regular job paid me $15,000 a year, not a lot of money in 1973 and 1974. The mayor then, Abraham Beame, paid me $10,000 a year more to help organize the tenants, so I lived on about $25,000 a year, and that was all right, because my interest was to develop a constituency.

“I know for sure thousands and thousands of residents were helped directly. No doubt about it. We went on rent strikes, and the strikes worked. I would go to two or three buildings a night. I had a secretary and a two-line phone in my little office, and I did it for years. I got grants. I worked every day of the week and often on Saturdays. The tenants lacked hot water, services in the building, there were broken windows, and roaches. Part of my job was to get the tenants organized. I inspected for the HPD, the city’s Department of Housing Preservation & Development. In those days the agency had the power of making emergency repairs. And that was another incentive for the landlord to fix up the building.

“We held back rents, and the landlords would negotiate with us. We had many successes, as well as a number of failures, either because the tenants were not well organized or because the landlord bought off the tenants. Look, it happens in every walk of life. The landlords had good lawyers.

“I ran for city council in 1973 against Sam Horwitz of Coney Island. My plans didn’t quite work out. The neighborhood at the time was represented by a landlord by the name of Leon Katz, who is now just a blessed memory. Leon was a landlord, owned many buildings, and although he himself was not a bad landlord, he was still a landlord, and how could the district be represented by a landlord when the majority of the people were tenants?

“There was a redistricting [creating the 33rd District of Brighton Beach, Coney Island, and a part of Staten Island], and the district no longer included where most of the apartments were. It became a large homeowner area. But I ran anyway, and the regular Democratic Party endorsed the regular candidate, and I lost by a few thousand votes. I put on a very sturdy campaign. It was the most fun campaign of my career. I came in second out of five candidates.

“So he won reelection, and he got rid of me. He became a council member and he was defeated years later by Bernard Marcus.

“The mayor appointed me to the Conciliation and Appeals Court from 1973 to the end of 1978, when State Senator Jeremiah Bloom, happily for me, wanted to run for the governorship against Hugh Carey, and he announced in the morning, and I announced I was running for his senate seat in the afternoon. Bloom put up his top person, Howard Silverman, his chief of staff, to run against me. I was part of the reform Democrats, and this time I won. I took office on January 1, 1979.

“I really did not like being a state senator in Albany. I loved being a state senator in Brooklyn. It was depressing in Albany. I lived in a hotel room. I didn’t want to rent an apartment, because I never wanted to live there. I always wanted to come home.

“In the senate I was always part of the minority party, since the Democrats have not had control of the state senate since 1955. Before that, they had control from 1932 to 1934. And before that, it was in the eighteenth century. The Democrats have been out of power in the New York State senate for almost the entire creation of the state.

“And the reason for that is simple: reapportionment. The Republicans cut up the districts in a way conducive to their winning. That’s how they did it. In the assembly, the Democrats do the same thing to stay in the majority. The only way the Democrats could take over the senate is if the voters get angry and vote the Republicans out.

“I stayed in the senate almost twenty-three years. I lived out of a suitcase in a motel in Albany, and as soon as the gavel went down, I picked up and raced back to Brooklyn. I knew what I really wanted to be: the borough president. I ran in 1985 against the then-incumbent Howard Golden. There were four candidates, and I came in second. After I lost, I figured I’d take one more shot at it, and when term limits kicked in, Howie had to go. Even if he didn’t have to go, I would have run, because at age fifty-six, it was my last chance, and a new generation of politicians was waiting right behind me, people in their forties waiting for their opportunity.

“On December 31, 2009, I will have to leave. Unless they change the law, which is unlikely, you can serve two terms, and then you leave, and that’s the end of it. Even if most of the residents of Brooklyn feel they’d like to have me stay, I can’t.

“When my term is up I will either run for mayor of New York City or call it a day in my public-service career. I don’t know which way I’m going to go. The good news is I will be almost sixty-five, and it’s not so bad.

“What I have tried to do as borough president is make the job relevant to the lives of Brooklynites. I have tried to make people proud of being Brooklynites. I have put a smile on their faces. And I think I’ve done a good job of providing programs for Brooklyn, whether it’s health care, affordable housing, bringing in the Nets in three years, which I believe will happen, or fixing up City Hall, which was neglected by every administration before Mayor Bloomberg. Those are my accomplishments.

“In my job I bring a little creativity. I didn’t want signs that said WELCOME TO BROOKLYN. That’s not Brooklyn. Brooklyn has an edge. We’re a bunch of meshuggeners. We are, and I’m proud of that. And I like that. I wanted the signs to reflect what we are. One of them is HOW SWEET IT IS! If you remember, Ralph Kramden [played by Bushwick’s Jackie Gleason on The Honeymooners] was a Brooklyn bus driver. Another is BELIEVE THE HYPE! And I also wanted to put up signs when you leave, such as OY VEY and LEAVING BROOKLYN—FUGHEDDABOUDIT. It’s a way to give a Brooklyn attitude. The people who come into Brooklyn should know they aren’t coming into a place that is like most other places. And it gives people a smile. They love it.

Marty stands besides his handiwork, the sign for motorists leaving Brooklyn, before it was hoisted onto the Belt Parkway exit for the Verrazano Bridge. Courtesy of Marty Markowitz. Photo by Katherine Kirk

“Not everyone loves me. Many of them don’t. But the great majority like the work I do. You can’t please everyone. You try to please everyone, but it’s impossible. Impossible. I try. I always try. But it’s impossible.

“Once a Brooklynite, always a Brooklynite. In 1957 we said sayonara to the Dodgers. Even though we have a great little team in Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Cyclones, a minor league baseball team, the truth is that Brooklyn is a major-league city, and it will be back in the major leagues when the New Jersey Nets get rid of the NJ and replace it with BROOKLYN in a beautiful, new, sparkling arena on Atlantic Avenue in downtown Brooklyn, opposite where Walter O’Malley—who we thought was the devil—really wanted to build a new Ebbets Field, right across the street, and Robert Moses destroyed that opportunity. But the good news is, that was then, we’re going to have a major league team in Brooklyn in 2010, and right now I’d say the number one sport in Brooklyn is football, second is basketball, and baseball and soccer are number three, and that’s the truth. Stay tuned.”

Like most Brooklynites who can remember the halcyon days of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Markowitz suffered unspeakable heartache when Walter O’Malley hijacked his baseball heroes and fled west to Los Angeles. It was an ache that never went away. When he campaigned to become the borough president, Markowitz announced that one of his goals would be to bring major league sports back to Brooklyn. Few took him seriously. But during his first weeks in office Markowitz called Dodgers’ owner Peter O’Malley and with a straight face asked if he might be interested in moving the Dodgers back to Brooklyn. His sales pitch: “Mr. O’Malley, it would be great for your family name and everything if you would consider moving the L.A. Dodgers back to Brooklyn.” O’Malley, not amused, declined.

Markowitz, who is nothing if not persistent, determined that he would bring to Brooklyn a major league sports franchise—any franchise, regardless of the sport—and to that end he began calling around to see who might be interested in buying a pro team and moving it to Brooklyn.

His first thought was Donald Trump. But Trump had a casino in Atlantic City, and Markowitz felt there was too much risk The Donald would move the team there and not to Brooklyn. Markowitz then considered Bruce Ratner, whose company Forest City Ratner had jump-started Brooklyn’s downtown renaissance when he built the huge MetroTech Center. By 2002 Forest City Ratner had become the largest developer in the city. Over fifteen years it had finished thirty-five commercial projects—six times the volume of all of their commercial competition combined in New York.

Ratner, who professed little interest in sports, told Markowitz no thanks.

Markowitz, convinced his idea had merit, kept calling Ratner back, two and three times a week. Eventually Ratner saw a way for both of them to fulfill their dreams. He figured out that if he could incorporate a sports arena into a plan for a truly grand development that included millions of feet of retail space and hundreds of apartments, he could own a big chunk of downtown Brooklyn and at the same time return to Brooklyn the sports glory that Markowitz envisioned.

The development, called Atlantic Yards, is on the site where Walter O’Malley wanted to build a new domed stadium for the Dodgers in the 1950s. It will stretch six blocks along the border of Prospect Heights and will include sixteen separate high-rise buildings, one of which was initially proposed to rise 650 feet into the air, towering over the nearby Williamsburg Savings Bank building and becoming by far the tallest building in Brooklyn. It has since been scaled back considerably.

Not surprisingly, Marty Markowitz is the project’s loudest drum-beater. He boasts that 50 percent of the housing will be for low-and middle-income residents whose incomes are between $18,000 and a $100,000 a year. Opponents rail loudly that Markowitz gave Ratner a sweetheart deal and are outraged that Ratner will be allowed to build on such a grand scale. Markowitz is unrepentant, and the plans to build the complex proceed unabated despite a series of lawsuits. In an office that is more ceremonial than power-wielding, Markowitz’s legacy is certain to be the Brooklyn Nets and the Atlantic Yards.

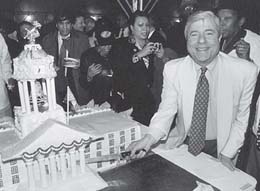

Marty cutting a cake in the shape of Borough Hall upon his election to the borough presidency. Courtesy of Marty Markowitz