Of all the natural habitats in the eastern United States, the hardwood forest is by far the most extensive. Extending from the borders of Canada, where it is in a constant struggle for survival with its coniferous neighbors, it spreads a verdant summer carpet southward across mountain and valley until it fades into the subtropic vegetation of the Gulf states. It reaches westward until inadequate rainfall and excessive transpiration cause it to surrender to the dominant prairie grasslands. From its primeval vastness of nearly half a million square miles, we have carved our great metropolises, our towns, our highways, and our farmlands. Yet despite these intrusions by man, and lacking most of its pristine state, the deciduous forest dominates our eastern landscape.

This great, green carpet does not enshroud the land in its entirety with any singular hue or texture. Stained and blotched by the trampling of three hundred years of “progress,” it struggles constantly to regain its pristine beauty and structure. In all degrees of growth, there is evidence that the forest seizes every opportunity to reclaim the land for its own.

In the southern Appalachians, this struggle ends in a climax forest dominated by the cucumber tree, beech, tulip poplar, sugar maple, white oak, buckeye, and hemlock. This is the geographical heart of this vast forest realm. It is the oldest exposed land mass of the region, and scientists believe a similar forest has existed here since Tertiary times. It is also believed to be the center of origin for many of the widespread hardwood species. Here there is a great variety of trees, and the biological associations are quite complex. There are perhaps twenty or more species (in addition to those just mentioned above) that could be part of a climax condition.

In the northern portions of this mixed mesophytic forest, the beech and the sugar maple strive for supremacy. As the broken forest reaches westward into Wisconsin and Minnesota, the beech gradually gives way to the basswood. A large portion of our eastern coastal forests were dominated by an oak-chestnut association until the Asian chestnut blight made its appearance in New York City in 1904. Forests along the mountains from New England to Georgia were affected by this deadly disease. A variety of oaks, tulip poplar, and some hickory are the prevailing species today. Even in the hardwood’s most southern range, the oaks (in different varieties and association) preempt the enduring forest. Mixed with them are the gum, ash, dogwood, hackberry, and a variety of shrubs.

This great American forest, enriched with ecological diversity, provides homes, food, and shelter for numerous endemic species of birds and wildlife. Even man seeks its sanctuary, for it is in these same middle latitudes—where the hardwood forest flourishes in all its richness and beauty—that man has clustered in the greatest numbers.

Quiet and subdued in the cold grasp of winter, the leaf-less trees stand bleak and lonely in a steel-gray world. The pulse of life is slowed, and all but the hardiest of creatures lie snug in the torpor of hibernation. But there are those who must defy winter’s cruelties and keep the pulse of life astir. The fox plies his stealth in the silence of the darkest night. His coat is thick and warm; he does not mind the cold as long as he can satiate his hunger. The tiny shrew, voracious and bloodthirsty, must hunt almost continuously in order to survive. Neither day nor season gives him rest from his foraging. The cottontail rabbit and the white-tailed deer browse upon the tender shoots of young trees and shrubs—the forest must not be choked by its own lush growth. The staccato hammering of woodpeckers resounds from hill to hill; there are no leaves to buffer its resonance. Chickadees and nuthatches join them in their search for grubs and insect larvae. Visiting grosbeaks, finches, and siskins reap a harvest of late-clinging seeds.

Life within the winter woodland continues—now dormant, now active. Not until the wandering Earth exposes its northern latitudes to the more vertical rays of the warming sun will life resume its hastening pace.

The coming of spring is inevitable. Slowly at first, and then with a resurgence of life that fills the forest with the colors, the sounds, and the aromas of a newborn season, spring emerges.

In the low wetlands, the skunk cabbage and the marsh marigolds have thrust through the mucklike forest floor; the maples are tinged with red, and the spicebush spreads a yellow haze through the valley. The “kon-kor-reee” of the male red-wing can be heard along the stream’s marshy borders. Higher on the ridge, the aspens are draped with fuzzy gray catkins. The ruffed grouse relishes them and welcomes the change in diet. The black and white warbler is there, too, searching the trees for the first hatch of insects. The first butterfly of spring, the mourning cloak, emerges from its winter cocoon and flashes its golden-edged wings. And the sweet smell of arbutus is wafted on the warming winds along the sunny hillside.

Now the flow of spring surges in every forest vein. The bloodroot and the hepatica are in bloom; May apples, wild columbine, Solomon’s seal, and bellwort must make their maximum growth before the closing forest canopy deprives them of sufficient light. The fringe-loving dogwood wraps the forest in a tattered ribbon of white. The songs of birds resound from every level—the ovenbird from the forest floor, the wood thrush from his low perch, and the scarlet tanager from the highest tree. There are warblers and vireos, grosbeaks and orioles, flycatchers and buntings. The rushing tide of spring has reached its crest.

Spring: the season of flowers, songs, mating, birth, and growth—the season of life renewed!

Spring: the season that beckons the inherent traits of man—the season when those of us who are interested in birds must answer the woodland’s call!

As you leave your car and the sterile ribbons of concrete behind you and step into the cool shade of the forest, you are entering the most dynamic of all outdoor communities. You walk down the trail, rest on a decaying log, and survey the green world about you. Everything you see, hear, touch, or smell is in some way involved in a life-building pyramid of ecological events necessary for the forest’s survival. The birds you came to watch fill a significant niche in this mounting struggle for life’s energy.

The square foot of soil beneath your feet is a compact mass of energy that is being produced, stored, and used simultaneously. Its tiniest creature, the soil bacterium, makes its bid for dominance by the simple and rapid procreation process of dividing itself into two complete individuals every half-hour or so. Biologists tell us that if all the offspring of one such bacterium survived, their bulk would be larger than the earth in less than a week. As the soil lives, the energy cycle of control evolves. Protozoa and fungi are the most abundant, but they are preyed upon by mites, springtails, millipedes, and other animals. Earthworms, beetles, weevils, ants, larvae, and grubs build the pyramid higher. They, in turn, are subject to predation by shrews, moles, mice, and ground-feeding birds. Many of the larvae are transformed into insects and spend their adult lives amid the green foliage. Now the insect-eating birds help maintain the ladder of diminishing numbers. The pyramid is now above ground, and the energy-producing processes begin building toward the pinnacle.

The leaf-brown floor of the deep forest is home to the most mysterious and secretive of our woodland birds. The call of the ovenbird resounds loud and clear with unmistakable tones—a call of “teacher, teacher, teacher,” that grows progressively louder. But this ecstatic song is deceptive as to distance, and the bird is not easily found. The woodcock is so secretive and blends so well with the forest floor that it can spend an entire nesting season near a well-traveled pathway without being discovered. The ruffed grouse sits tight and unnoticed until it explodes from near the intruder’s feet with a startling whir of pounding wings.

Like the wood thrush, the ovenbird and the woodcock have comparatively large eyes adapted to the subdued light of the shaded forest. The ovenbird likes to sing from a log or fallen limb that gives it a slight elevation above the forest floor. This is where it is noticed most often. Once it is found, there is nothing reticent about its actions. If one watches quietly, it will continue to sing, or it can be observed walking across the matted leaves, flipping them aside in search of insects. The walk is deliberate and accompanied by a “jerking” or “wagging” of the tail. This action has resulted in such colloquial names as “wagtail warbler” and “woodland wagtail.” The diet of the ovenbird consists mainly of the small creatures found in the upper strata of the forest floor—earthworms, slugs, snails, beetles, weevils, aphids, crickets, ants, and spiders. It also includes some flying insects.

The ovenbird gets its name from the type of nest it builds—an ovenlike structure, roofed over and with a single entrance. It is built on the ground, usually near an opening in the forest or along an old trail, making flight approach easier. The nest is built of a variety of materials including dead leaves, rootlets, bark, moss, and grass. It is lined with fine plant fibers or hair. The nest is so well camouflaged that it is usually discovered by flushing its occupant. Even then it is not found so easily, as the ovenbird will leave the nest and walk several feet away before taking flight.

Woodcocks are rather crepuscular in most of their habits. It is during the twilight hours that we see them settling into the alder and maple bottomlands. They come in singly—not in flocks. They must find soils well supplied with earthworms, for this is their main source of food. They are early spring migrants moving northward with the receding frost line; arrival in New England is as early as the latter part of February or the beginning of March.

The woodcock is a chunky quail-size bird with a long bill. The upper mandible is sensitive and somewhat flexible, enabling the woodcock to feel and capture earthworms by probing. Its large eyes, set well back on the head, are out of the way and allow it to see in all directions when in this rather precarious feeding position. Being mostly nocturnal, the woodcock is rarely seen in the actual process of feeding, but its tracks and borings are often visible in the low flat mudlands.

The dead-leaf coloring of the woodcock, its principal means of protection, gives it a deep trusting sense of security. It is a tight sitter and will not flush until nearly stepped upon; then it zigzags through limbs and treetops and settles down again 50 yards or so away. When it is nesting in a depression of brown leaves, one can look intently at the nesting site without seeing anything unusual. Not until the large eye is noticed is it possible to discern the shape of a bird. The woodcock has a spectacular courtship ritual. Since it takes place mostly in the darkness, it is described in Chapter 15, “Birds in the Night.”

The woods of spring are filled with the exuberant sounds of life, but none is so profound as the drumming of the ruffed grouse. The male seeks a large log on which he can strut and display his prowess—and this he does in a grand manner. First he puffs out his chest, ruffs a ring of neck feathers to frame his profile, and expands his banded tail in fanlike fashion. He then struts back and forth on his stage like an egotistical performer surveying his audience. The wings are extended and held momentarily. All is quiet. The baton falls, and the performance begins. With a forward and slightly upward stroke of the wings, he compresses a pocket of air against his inflated chest. The resulting boom resounds through the forest. The drummer pauses for an instant; all seems well and the beat continues. Slowly, at first, it reverberates, and then with a rapidly increasing blur of wings, until the final flourish echoes like the muffled roll of distant tom-toms.

Wallace Byron Grange describes the ruffed grouse’s drumming as: “Thrump! Thrump! Thrump!” “Thrump —– Thrump —– Thrump — Thrump — Thrump – Thrump – ThrumpThrumpThrump ThrumpThrumpThrumpThrumpThrump-p-p-p-p-p-pppp pppppppp!”

Arthur Cleveland Bent writes of it as: “the throbbing heart, as it were, of awakening spring.”

The diet of the ruffed grouse is quite diversified, consisting of nuts, seeds, buds, catkins, foliage, wild fruits, and a variety of insects. During the summer months, when the birds are rearing a brood of young, they feed mostly on or near the ground. The young leave the nest as soon as they are dry. Their mother teaches them to forage among the leaves for worms, beetles, larvae, flies, ants, snails, and spiders. Strawberries, blueberries, dewberries, and low-growing blossoms and buds are also a part of their summer diet.

The female grouse is a very protective mother. I remember an occasion when I surprised a female leading her brood across an old lumber road. She immediately fluffed her feathers, spread her tail, and went into a charging rage. When this failed to deter me, she feigned a broken wing and went fluttering off across the forest floor. Her ruse worked. I was so busy watching her performance that I didn’t notice the chicks disappear into the surrounding cover. I’ve no doubt that such a devoted mother could give an inquisitive snake or small mammal a rough reception.

Adult ruffed grouse are primarily browsers. The buds and flowers of aspen, hazelnut, birch, and apple are favorits foods. They also relish the leaves of clover, sheep sorrel, wintergreen, greenbrier, and numerous woodland plants.

It is an interesting, and sometimes humorous, sight if one is lucky enough to see grouse in the process of “budding.” They will fly onto the limb of a favorite tree and proceed to pick the buds one after another. They work their way out toward the tip of the limb (where the most buds are) until they have to employ all sorts of contortions to keep their balance on the flimsy branches. Finally they give up, fly to a new limb, and start the process over again.

When the day’s light fades from the forest, and most of its diurnal creatures have quieted for the night, the bell-like tones of the wood thrush peal from the darkening depths. In the Northeast and along the middle ridges of the Appalachians, this hour of song is sometimes shared with the veery, whose treble flutelike song spirals downward with a distinctive “whree-ur, whree-ur, whree-ur, whree.” Both species are primarily ground feeders, but there is a decided difference in their feeding habits. The wood thrush is a thorough hunter; it hops across the forest floor turning over leaf after leaf as it searches for insects. The veery seems more impatient; it will fly to a low limb, log, or stump, hop down to the ground, and feed momentarily. It will then fly to another low perch and repeat the process. The veery undoubtedly covers a wider feeding range than the wood thrush, but perhaps not so thoroughly.

The two thrushes also differ in the way they build their nests. Again, the veery likes to stay slightly above ground level. Lacking a low stump, tree crotch, or bit of brush, it will often build a mound of dead and rotting leaves, sometimes as much as a foot in height. The cuplike nest is lined in the center with dry leaves, rootlets, and plant fibers. The wood thrush prefers to nest 6 or more feet above the ground in understory trees and shrubs. The forked crotch of a dogwood limb is a favorite location. Its nest is somewhat like that of a robin. It uses mud to bind together decaying leaves, rootlets, grass, and weed stems. The wood thrush has the singular custom of placing one or more pieces of something white (rag, paper, or a bleached leaf or grass blades) in the exterior edge of the nest. The reason for this is still a matter of conjecture, but the most plausible explanation suggests this peculiarity is an attempt to break the recognizable contour of the nest. This theory is further substantiated by the fact that brooding females, or fledglings still in the nest, will point their heads upward and display their white throats when disturbed.

Ground-nesting species are subject to the controlling law of predation. Eggs and young are sought by snakes, raccoons, foxes, skunks, weasels, and other creatures that prowl the forest by day or night. Survival is largely a matter of protective coloration and the instinctive understanding of how to use it.

We think of the forest as being shadowy—even dark—but light is one of the most predominant forces within this woodland realm. Growth is controlled largely by surface areas exposed to light. As springtime advances and the rising sap pushes the swollen buds into leaf, plants compete for the direct rays of the sun. Gradually the canopy closes, and the forest is “roofed over” with a lacy pattern of overlapping leaves. This green roof now becomes a controlling factor in the climatic changes and living conditions within the forest. It not only influences the amount of light reaching the understory, but affects the temperature and humidity as well—physical factors that modify, or in some way become a part of, the intricate life cycles of all woodland creatures.

The yellow-bellied sapsucker welcomes this resurgent flow of the trees’ sweet juices. They will be a stable part of its diet throughout the growing season. The green leaves, tender and abundant, become the basic link in countless food chains that transport the forest’s energy on a circuitous route of interdependence. It is the time of insects—the time when their myriad numbers threaten to denude the forest of all living matter. But it is also the time of birds—the time when they, too, are at the peak of their abundance. Permanent and summer residents expend their energy in preparation for the ensuing nesting season. They are joined by a flood of transients wending their way northward. Birds are present in such numbers and varieties that every niche of the forest is subject to their specialized hunting techniques.

The sapsucker sets its trap by drilling a hole in the bole of its favorite tree. It drinks the sap and eats the cambium, the tender layer between the bark and hard wood. The hole is drilled at a slightly downward angle, and acts as a miniature reservoir. When this reservoir overflows, and the sap runs down the tree, the sapsucker is very careful not to get this sticky substance on its body feathers. (If you watch a sapsucker feed, you will notice that only its feet and the spiked tips of its tail touch the tree.) The dripping sap attracts ants, moths, and a variety of other insects; ants are an important part of the sapsucker’s diet. Numerous birds find an easy meal among the trapped insects; the ruby-throated hummingbird and the Baltimore oriole will sometimes drink from the tiny reservoirs.

During the nesting season, when the demand for food is greatest, the sapsucker’s drillings are more numerous. It will drill a series of holes in its “orchard,” and tend them as prudently as a New Englander would tend his sugar-bush.

The trunks and limbs of forest trees are subject to the close scrutiny of a variety of birds especially adapted to this purpose. The tiny brown creeper starts at the base of a tree and spirals its way upward, hitching along in woodpecker fashion. With its long, curved bill, it probes into deep crevices and behind bits of scaling bark, where it finds small beetles, weevils, ants, spiders, and the larvae, pupae, or eggs of numerous insects. The white-breasted nuthatch searches the tree from a different angle; it starts high and works downward in a head-first position. The black and white warbler, unlike most other members of its family, hunts extensively on the trunks and larger limbs of trees. It is like both the creeper and the nuthatch in its actions; it would just as soon feed coming down the tree as going up. Also, it will leave the trunk of the tree, dart into the air, and catch a flying insect in typical warbler style. The woodpeckers inspect the trees from still another viewpoint; with their chisellike bills, they will drill through the bark in search of cambium-feeding and wood-boring grubs. Tanagers and wood pewees patrol the upper reaches of the larger trees.

The forest’s multilayered canopy is subject to increasing hordes of rapacious insects. They are present in such numbers and varieties that every tree and shrub is a potential victim of their foraging. There are leaf-chewing and leaf-mining specialists; others are specifically adapted to eating wood or seeds. Populations are kept within reasonable balance mostly by climate and the abundance of their enemies, especially birds.

Vireos, flycatchers, and certain warblers are common birds of the deciduous woodlands, and they find this great variety of insects much to their liking. The vireos and warblers are quick of flight and are persistent hunters. The flycatchers are watchers; they sit on a favorite perch and dart into the air to catch passing insects. The red-eyed vireo and the redstart (warbler) are the two most abundant birds of our eastern hardwoods. It is reasonably safe to say that every deciduous woods, large or small, from northern Florida to the Canadian border will have at least one pair of nesting red-eyes. They are sometimes joined by other vireos—the white-eyed, the yellow-throated, the warbling, and, in the northern hardwoods, the Philadelphia. But none is so plentiful as the red-eyed. The redstart is at home in the second-growth woodlands from Georgia and Alabama to the Gulf of St. Lawrence and central Manitoba.

Other species of warblers particularly partial to this diversified habitat include the hooded, worm-eating, cerulean, Kentucky, and waterthrush (warbler). Invariably, the Kentucky warbler is found in the low, moist bottomlands, and the waterthrush along woodland streams. The cerulean is a bird of the treetops, and by contrast, the hooded and worm-eating prefer understory thickets.

The great crested flycatcher is the largest member of its family to nest in our eastern woods. It is nearly robin-sized in length, but not quite so plump, and is easily recognized by the long rufous tail and yellowish breast. This is the only flycatcher we will find nesting in cavities. Like the wood thrush, the great crested flycatcher has adjusted to the encroachment of civilization. It will often abandon its woodland habitat to nest in old orchards and open parklands. The same could be said of the least flycatcher; it, too, can be found in the open woods, orchards, and groves. The Acadian flycatcher and the wood pewee still prefer the shaded woodlands, but the phoebe often nests under bridges and the eaves of buildings. The smaller flycatchers are distinguished best by their calls, as the birds are quite similar in shape and coloration. To me, the Acadian says “wits-see” with a rising inflection, while the least flycatcher has a definite and choppy “che-bek.” The phoebe and wood pewee are quite similar in appearance, but each one calls its own name, making recognition quite easy. The phoebe has a phonetically correct “phoe-be.” The wood pewee whistles a slow, drawn-out, “pee-a-wee.”

The scarlet tanager, the summer tanager, and the rose-breasted grosbeak are among the most colorful of our woodland birds. Both species of tanagers are sometimes referred to as “the guardians of oaks,” for it is among these dominant trees that they like to nest and feed. They consume large quantities of insect eggs, larvae, moths, beetles, weevils, caterpillars, and other infectious creatures to which the oaks are a helpless host. Both tanagers are nearly starling size. The males are red, but the male scarlet tanager is distinguished by his coal-black wings. The females are more easily confused—olive backs and yellowish breasts—but the darker color of the scarlet tanager’s wings is the perceptible difference.

The rose-breasted grosbeak is slightly larger than the starling. The male has a big red “strawberry” on an otherwise all-white breast. His head and back are mostly black, making a striking contrast with the white underparts. His mate reminds you of the female red-wing, but the large seed-eating bill is very pronounced. The animal portion of the rose-breasted grosbeak’s food is similar to that of the tanagers, but seeds, buds, and wild fruits make up approximately 50 percent of its diet.

Tanagers and rose-breasted grosbeaks are more plentiful than the novice birder realizes. Their songs are somewhat similar to those of the robin and the red-eyed vireo, and often they are not noticed by the untrained ear.

The great diversity of plant life in the deciduous forest provides a multiplicity of nesting materials and home sites for birds. Just as certain species are adapted to feeding in definite niches within the forest, so are they inherently adapted to using specific materials and locations for their nests. Virtually every substance is used, and all forest levels occupied, by one species or another. But it is the understory trees—the dogwoods, the witch hazels, the hornbeams, and a variety of shrubs and saplings—that are most densely occupied. Here in this shaded layer, we find the homes of the woodlands’ master architects: the vireos.

The red-eyed vireo builds a cuplike nest suspended from a forked branch of a horizontal tree limb. Watching a pair of red-eyes build their beautiful pensile home, a person is reminded of one of nature’s great mysteries. How do a pair of young red-eyes (or the young of any species), returning to the forest for the first time, know what materials to use and what procedures to follow in order to build a model home singularly characteristic of its species? They do not serve an apprenticeship, nor do they have a supervisor to show them what to do. We credit them with an innate sense of perception, but this only adds to the mystery of their actions. Let us watch a pair of red-eyes build their nest so that you have a better understanding of what I mean.

If we are lucky enough to observe the nesting site from the very beginning, we will see considerable hopping back and forth across the selected fork. This is undoubtedly a period of determining whether that particular fork is satisfactory, especially as to size. (I believe that mistakes are made sometimes, because I do not know of another reason why red-eyes will occasionally dismantle a nearly completed nest and use the materials to start a new one nearby.) The actual nest building begins by suspending rather long fibers, usually the supple strands of grapevine bark, from both twigs of the fork. These are “sewed” fast with spider webs, webbing from canker worms and caterpillars, or the silk from various cocoons. More fibers are hung in the same way until there is enough to begin weaving them together to form the bottom. The nest now has a basketlike appearance. This miniature basket is strengthened by adding bits of bark (usually birch), rootlets, fine grasses, paper from wasps’ nests, and portions of dead leaves. All loose ends are woven in, and the whole nest is bound together with quantities of silk and webbing. The outside is usually decorated or camouflaged with bits of lichens.

Although our woodland warblers are quite similar in size and feeding habits (insect-eating), they are quite diverse in their choice of nesting sites. Every level of the forest is utilized, from the floor to high in the canopy. The ovenbird is not the only ground nester of this family. The worm-eating warbler builds a similar nest amid wind-drifted leaves next to an old log or stump, or against the base of a tree. The black and white warbler and the Kentucky warbler will nest on or very near the ground. We look for the nest of the hooded warbler in the densest of thickets, usually no more than 2 or 3 feet above the ground. It is quite partial to thick clumps of laurel and rhododendron. The redstart nests in the understory, but the cerulean secludes its home high in the taller trees.

The redstart is not only the most common warbler of our deciduous woodlands, it is also the most colorful. The male is a striking pattern of orange, black, and white. He is quite cognizant of his beauty and uses it extensively in courtship and territorial displays. He patrols his selected territory with vigor, flashing his orange-banded tail as a warning to all would-be intruders. When courting a female, he also spreads his wings and tail, displaying his brilliance in a most captivating manner.

The usual nesting site of the redstart is in an understory sapling or shrub. The nest is securely wedged into a vertical crotch with three or more branches. The female builds the nest of rootlets, grass, and fibers of bark. The interior is lined with whatever soft material can be found—animal hair, feathers, or fine plant fibers. The outside may be finished with bits of lichens, bud scales, or seed pods.

Still more niches within the forest provide home sites for additional species. The brown creeper tucks its nest behind some loosened bark on the trunk of a tree, the lone white pine may be the home of a long-eared owl, and the dancing shadows on a sparse section of the forest floor may camouflage a brooding whip-poor-will. The grosbeaks and tanagers add their numbers to the populous understory, and the phoebe seeks shelter under an overhanging ledge or against the base of an upturned tree.

As the lush growth of summer tightens the canopy over the forest, plants, too, become involved in the constant struggle for life-sustaining energy. Some must die so others may live. Those that reach the direct rays of the sun, or receive sufficient reflected skylight, will survive; others will succumb in the darkening shade. The natural processes of pruning and thinning begin. Many lower limbs and young trees will die from overcrowding and the lack of light; others will survive to reach ever higher toward the original source of all energy. But nature will continue to harvest the forest in many ways. Wind storms will damage limbs and trunks and uproot entire trees; insects and disease will follow, and the trees will die. Even fire sometimes exerts beneficial controls, for certain trees must have a barren seed bed to perpetuate their own kind. Without periodic fires, they cannot survive.

The mature forest soon heals its wounds, but the scars of broken limbs and trees remain. This is a part of nature’s scheme, for now the woodpeckers and other cavity-nesting specialists forage and live among the dead and dying. The dead will be returned to the soil, keeping the energy cycle intact.

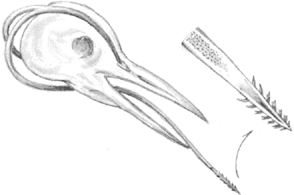

Through the ages, woodpeckers have evolved as specialists, and they fill a particular niche in the delicate balance of the outdoor community that is not covered by other species. Their bills are long, heavy, and chisel-shaped for drilling through bark and wood. The woodpecker’s tongue is exceptionally long and barbed; it can be extended far into drilled holes and the cavities of wood-boring larvae or grubs—its favorite food. When recessed, the long tongue is curved upward and forward following the contour of the skull. The bird’s skull is unusually heavy, protecting the brain from the shock of drilling. The feet of most woodpeckers have two toes forward and two toes rearward to give them better grip and balance when climbing trees. (The three-toed species are exceptions.) Tails are stiff and spine-tipped; they serve as props when the woodpeckers are climbing or drilling.

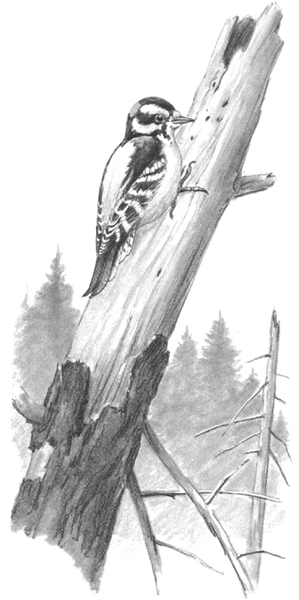

As you sit quietly on your log seat in the woods, you will undoubtedly be treated to the entertaining antics of the downy woodpecker. First you will hear it tapping on some distant tree. You will be tempted to get up and go searching for this familiar woodland sound. But there is no need to move; the downy has probably spotted you already; sooner or later, its inquisitive nature will prevail, and it will move close enough for you to observe each other. The approach will be gradual, first to one tree and then to another, each move bringing it closer to you. Finally, it will settle on the trunk of a tree and pretend to feed. Notice how it hitches up, down, and sideways on the trunk, and how it weaves its head from side to side at each stop. As you observe these actions, you will also notice that the downy is busy all the time and, seemingly, is not a bit interested in your presence. The downy never looks you straight in the eye.

Now watch closely, and you will see how a woodpecker leaves a tree. Using its feet (and sometimes its tail as well), the downy springs backward, turns, and dives to pick up immediate flying speed, all within the fraction of a second.

The hairy woodpecker is not as easily observed as the downy. Although the range and the type of territory inhabited by each species are nearly identical, the hairy is considerably rarer and much more seclusive than the downy. Many smaller woodlots may not harbor a single hairy, but still provide homes for several pairs of downy woodpeckers. Look for the hairy in the deeper woods, and listen for its loud kingfisherlike call, or its loud distinctive drumming. At first the downy may fool you, but once you see and hear the hairy, you are not likely to be mistaken again.

The hairy’s tree-climbing techniques are similar to those of the downy, yet somewhat individualistic. It will sometimes use a creeping motion and spiral about a tree in a manner reminiscent of the brown creeper or the black and white warbler. When it is being observed, it will work mostly on the far side of the tree, hiding much as a squirrel would do.

The feeding and nesting habits of both species are comparable. The largest single item in their diet is the larvae of wood-boring beetles, often as much as 75 percent; ants comprise about another 20 percent. The waxy fruits of such plants as sumac, poison ivy, and bayberry supplement this diet, particularly in the winter. Both are cavity nesters, and they usually drill their holes in a dead limb or in the trunk of a dead tree. The cavities are gourd-shaped and up to 12 inches in depth. A few fine chips are left in the bottom as nesting material. The hairy will often return to the same nesting tree year after year, as long as the structure is sturdy enough to support another family.

The most wondrous of all our woodland woodpeckers is surely the pileated. Big and handsome, it works in the larger timbered areas with the skill of a lumberjack. It is really an exciting experience for the birder who sees this crow-sized woodpecker for the first time. The contrasting black and white coloration and the conspicuous red crest make identification unmistakable. (The nearly extinct ivory-billed is the only other woodpecker with a crest.) Its behavior is equally distinctive. I think I can describe it best by telling about my luckiest observation of this species.

I was in a remote section of Maine, some 10 miles or so north of Lake Kenebago, following a woodland trail en route to a small lake to do some trout fishing. A pileated woodpecker soared across the trail several yards in front of me and, with a few rather slow, rhythmic wing beats, lifted itself up about 30 feet onto the trunk of a decaying sugar maple. There was an immediate call, loud and strong, that sounded like a continuous run of the syllables “wuck-wuck-wuck-a-wuck.” It disappeared on the far side of the tree, and I seated myself amid the low branches of a small beech tree to watch the proceedings; the trout fishing could wait. The maple was obviously a current feeding tree, for there was one vertical trench about 2 feet long already dug, and the interior wood seemed bright and fresh. At first the pileated was a bit reluctant to resume its drilling. It would hitch around the tree, weave its head from side to side in typical woodpecker fashion, and then seclude itself on the far side again. After repeating this act a few times, it started to chisel a new trench a foot or so below the first one. The outer layer flaked off quite easily, and the big woodpecker was soon working on the hard interior wood, obviously cutting its way into a colony of large black timber ants—the main item of the pileated’s diet. I was amazed at the size of the chips that fell to the ground. (Later checking proved some of them to be 3 and 4 inches long.) Actually, some were more like long splinters, and considerable chiseling took place before they fell.

I watched this woodpecker for 10 minutes or more from a distance of about 200 feet, but I never did get to see it feed. It left the tree suddenly with an alarming cackle of “ka-ka-ka-ka.” Later in the day when I was fishing on the lake, I could hear the loud drumming roll of the pileated. It may have been the same bird, but I was more than a mile from where I had seen it.

The range of the pileated woodpecker extends from southern Canada southward through Florida and the Gulf states, but it cannot be considered a common bird. It undoubtedly suffered a depletion in population after the harvesting of our virgin forests. Now there are indications that its numbers are on the increase once again. Many second-growth hardwood and mixed forests have increased sufficiently in size and extent to support this rather exacting woodpecker.

The typical nesting site of the pileated is a large, dead tree stub, usually in a remote section of the forest’s bottomlands. The pileated will return to the same nesting tree for succeeding years, but it will always excavate a new cavity. I have known abandoned cavities to be occupied by screech owls and by wood ducks.

Although the red-headed woodpecker, the red-bellied woodpecker, and the flicker are often found in open woodlands, they can hardly be considered true forest birds. Today, these species are more at home in gardens, orchards, groves, parks, and similar open areas. For this reason they will be considered elsewhere in this book (see the index).

Woodpeckers’ importance as destroyers of insects is quickly recognized, but they make additional contributions to the functioning of the outdoor community that are not noticed so readily. Their drillings and excavations hasten the return of decaying trees to the forest floor. Also, the vacated cavities provide homes for many woodland creatures.

As you wander through the woods, you will notice numerous old woodpecker holes in dead stubs and trees. These are the abandoned homes from previous years, but now many of them have new tenants. The most common hole nesters which follow the woodpeckers in our eastern hardwoods include the black-capped chickadee, Carolina chickadee, tufted titmouse, white-breasted nuthatch, and great crested flycatcher.

Chickadees have long been known as the most sprightly and the most cheerful of our woodland birds. And rightly so, for their familiar “dee-dee-dee” welcomes you to the forest at any time of the year. They are so trustful of man that they will often accompany you along the trail, flitting from tree to tree so close that there is usually no need to use binoculars. As you watch them, you will often find their actions quite entertaining, for they seem to delight in showing off for a captive audience. Their flight from branch to branch is almost instantaneous—so quick that it is often difficult to follow, especially with binoculars. They are constantly on the move, searching for plant lice, insect eggs, spiders, caterpillars, ants, and other bits of food. They will often cling to the outermost bud on the tip of a swaying branch in an inverted position. At times, they will turn completely over in somersault fashion as they search for tiny morsels in a place not easily accessible to other species.

Both species of chickadees will nest in abandoned woodpecker sites, but more often than not, they will excavate their own nesting cavities. Frequently they will finish a site that was started previously by an exploratory woodpecker. Chickadees do not have strong powerful beaks like the woodpeckers, so they select a low, rotting stub of softer wood. They prefer a stub with a wraparound type of bark, such as gray birch or poplar. Often, this strong wrapping of bark is all that holds the stub together at the cavity area.

Considering their diminutive size, chickadees rear large families. The average clutch of eggs will number from six to eight, although ornithologists have recorded as many as thirteen in a single set. The young are heavily feathered when they leave the nest, but they have a decidedly disheveled appearance. It is an interesting sight to see them all lined up on a branch waiting for food. They look like a line of unkempt forest urchins waiting for a handout.

The impelling forces within a maturing forest provide homes for cavity-nesting birds in different ways. In addition to holes drilled by woodpeckers, there are many knotholes scattered throughout the forest as a result of the natural processes of pruning—overcrowding, storms, and insufficient light. When a weakened limb falls to the ground, the remaining scar is subject to moisture, insects, and disease. Gradually a cavity is formed, resulting in a favorite nesting site for the titmouse or the great crested flycatcher. Lightning will split a tree, and the deep cracks provide nesting crevices for the nuthatch. Each force within the forest produces a characteristic change that benefits certain members of the community.

Nature’s most violent methods of harvesting the forest—hurricanes, tornadoes, and heavy ice storms—bring about the most radical changes within the hardwood community. Limbs are broken, and trees are snapped and uprooted. The protective canopy is thinned or eliminated, and a gradual ecological change begins within the open forest. The thrushes, tanagers, grosbeaks, certain warblers, and other species may no longer find this habitat to their liking. But they will be replaced by those that do: towhees, thrashers, chats, buntings, and many more. The abundance of damaged trees and shrubs will eventually bring about an influx of cavity-nesting species adapted to this more open type of environment. Red-headed woodpeckers and flickers will be at home here; house wrens, bluebirds, and tree swallows will compete for the smaller cavities; sparrow hawks and screech owls may vie for the larger openings. These species will thrive here until the forest once again closes its canopy, and the deepening shade invites the return of thrushes and the vireos.

No matter how enticing the environment may be, or how abundant any one species becomes, nothing is allowed to increase beyond reasonable bounds. Nature exerts her relentless forces of control. An abundance of nesting sites is of little value if the surrounding territory lacks sufficient food to support the ensuing families. As the increased population competes for food and cover, the weak and the exposed are prey for patrolling predators. Thus, nature retains the strongest and most alert individuals to propagate the species.

Predation within the bird community exists in many forms. Body lice or internal worms may weaken the individual, making it an easy capture for the sharp-shinned or the Cooper’s hawk. The cowbird’s parasitic habit of laying its eggs in the nests of other birds undoubtedly limits the number of the host species that will survive. The destruction of nests by reptiles and mammals restricts population numbers. Hawks and owls patrol wide areas and help harvest the excess crop.

Among our eastern hawks, three species of buteos—the red-tailed, the red-shouldered, and the broad-winged—are the most common residents of the deciduous hardwoods. The red-tailed is the most widely distributed, but in certain areas of its range it is outnumbered by the red-shouldered or the broad-winged. Two of the accipiters, the sharp-shinned and the Cooper’s hawk, are present in limited numbers, although they have a preference for coniferous or mixed forests. They are seen most often darting through the understory in pursuit of some smaller bird.

The red-tailed hawk and the broad-winged hawk prefer the drier upland sections of the forest, while the red-shouldered hawk is more at home in moist bottomlands and timbered river valleys. All three species show a preference for areas of larger timber, not for reasons of protection, but because it is more open and better suited to their hunting techniques.

In the spring, the buteos announce their arrival by soaring above the woods and uttering their calls of defiance against possible intruders. The red-tailed circles and cries “keeer-r-r-r” on a descending scale. The call of the red-shouldered is a pronounced two-syllable whistle: “kee-yer, kee-yer.” The broad-winged whistles a long-drawn-out “k-wee-e-e-e-e-e.”

Buteos have similar requirements for nesting sites and food, and therefore are not particularly tolerant of each other. You are not likely to find a red-tailed and a red-shouldered occupying the same territory. However, either species will permit one of the accipiters to nest nearby without any noticeable difficulty. Both species nest high (usually 30 to 75 feet above ground) and build their nests in a sturdy crotch against the trunk of the tree. The nests, constructed of sticks and twigs, are lined with strips of pliable bark, dry leaves, moss, and down from their bodies. On occasion, they will rebuild their old nests or build upon the foundations of nests originally constructed by crows, squirrels, or owls. When rebuilding such a nest, they will stake claim to it by placing a fresh green twig on the nest. This is especially true of the red-tailed hawk.

The red-shouldered hawk and the barred owl are quite compatible. A. C. Bent, in his Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey, gives this account: “I have always considered the red-shouldered hawk and the barred owl as tolerant, complementary species, frequenting similar haunts and living on similar food, one hunting the territory by day and the other by night. We often find them in the same woods and using the same nests alternately, occasionally both laying eggs in the same nest the same season, resulting in a mixed set of eggs on which one or both species may incubate.”

The broad-winged is considered to be the tamest of our hawks, yet it is chiefly a deep-woods bird. Like the red-tailed and the red-shouldered, it feeds on small mammals, an occasional bird, and the larger insects. It will also perch along the edge of a pond waiting for a chance to capture snakes, crayfish, toads, frogs, or even an unwary minnow. The nest of the broad-winged is a comparatively flimsy structure, especially when it lacks the base of some other old nest. Like most hawks, the broad-winged rears a small family, averaging two eggs per set.

The broad-winged is typical of the many hawks that have a habit of keeping the nest furnished with one or more twigs of fresh green leaves. Just why they do this has long been a debatable subject among ornithologists. Some believe it is done for sanitation purposes; others believe it is a simple matter of decoration or camouflage. And there are those of a more quixotic nature who believe it is a sign of devotion for the mate—a bouquet of roses for the expectant mother.

And so the forest survives. And so the creatures that it shelters survive, in a balance according to the food and cover it supplies. Trees, shrubs, and ground plants continue their role as basic builders of life, by capturing the energy from the sun and the elements from air, soil, and water. Insects increase in multitudinous numbers, and are preyed upon at every level within the forest. Most are destroyed, but some must survive to pollinate the forest, to help remove the dead, and to propagate their own kind. As the never-ending struggle for life’s energy continues, the pyramid of surviving numbers grows higher and narrower with fewer and stronger species at each succeeding level. In the forest community, the hawk, the deer, or the bear may reach the pinnacle, for they have few enemies other than man. But even they must succumb to nature’s ways, and eventually surrender their place to the young and the strong. And yet, even in death, the energy cycle continues, for now the scavengers—vultures, crows, and beetles—come to the fore to claim their share. And then the bacteria, fungi, and mites return the remaining bits to the soil. The cycle is complete, and the same atoms of energy once again surge through the veins of the forest.