For many long days and nights the pond lay beneath a smothering blanket of ice and snow. But now the warm rays of a spring sun challenge the cold’s indomitable reign over the land. The ice cracks and rumbles like distant thunder. The snow thaws, and water pours into the pond in tiny rivulets and surging streams. The cold makes one last effort to exert authority, but its grasp is short-lived, for all things must yield to the will of the sun.

The pond was formed thousands of years ago by the awesome power of a glacier. The creeping stream of ice gouged out the soil and pushed it along like a blade of a giant bulldozer. Eventually, the glacier’s great power waned before the dominant forces of the sun. The ridge of soil and rock formed a dam across the small valley; the ice melted and filled the depression: a new pond was born. The pond was sterile then, but nature immediately began the long, slow process of reclaiming the land. Throughout succeeding years, soil and vegetation washed into the pond. Microscopic organisms became the pyramidal base for other forms of life that would find their way to this new environment. Year after year, the sediment accumulated; new and varied plants grew in the enriched water and from the muck along its shallow edges. Numerous forms of wildlife increased in great numbers. Unknowingly, and in an infinitesimal way, they contributed to the eventual destruction of their own environment. Through plant distribution, procreation, feeding, and death, they aided the processes that would turn the pond back to dry land. Now, after millennia, the progress of this transition is quite visible: pond—to marsh—to wooded swamp—to forest.

The sun’s rays become warmer, and the last vestiges of winter disappear in the flood waters of springtime. The pond is suffused in a new supply of oxygen, and life therein, mostly dormant during the cold months of winter, responds to the reviving infusion. The time is one of awakening—the rejuvenation of myriad life forms that will make the pond one of the most populous and most active of all outdoor communities.

Life in one of its simplest forms, the plant plankton, floats in the lighted water near the surface. Countless billions of these tiny microscopic plants give a greenish cast to the water. Their function is twofold: through the process of photosynthesis, they provide the pond with a source of sugar and oxygen; also, they are a direct source of food for the animal plankton and for the larvae, nymphs, tadpoles, beetles, snails, and clams that are so abundant in the pond. Water striders, backswimmers, water boatmen, and whirligig beetles emerge from the rotting vegetation and debris on the bottom of the pond and find their way to the surface. The nymphs of mayflies, damselflies, and dragonflies forage along the bottom; eventually, they will leave the pond and, as winged adults, assume a new role in the life of the community. Diving beetles, salamanders, frogs, and turtles free themselves from an encasement of mud and seek the warmth and oxygen of the surface water.

Everywhere about the pond, life responds to the urgency of the season. Seeds and egg cases swell with the beginning of new life, and nymphs and larvae seek the sustenance to acquire adulthood. Along the pond’s edge, large gray tadpoles seek the shallowest and warmest water, but it will take another summer to complete their transformation into bullfrogs. The crayfish have unplugged their winter burrows and feed upon sow bugs and other tiny pond creatures. The earthworms have untangled themselves from the massive balls of hibernation and tunnel toward the surface. The willows have an apple-green hue, and the swamp maples are tinged with red. From the cattails comes the first “konk-ka-ree” of the red-wing, and in the evening, the plaintive “peent” of the woodcock can be heard. These are the first arrivals of the many birds that will depend upon the pond throughout the spring and summer.

Each pond or small lake can be looked upon as a microcosm—an isolated habitat mostly self-contained and largely independent of outside influences. However, each body of water and the life that it supports are affected by such factors as temperature, soil content, and whether it is located in an open or wooded area. Regardless of its physical characteristics and biological contents (barring excess pollution), the lone fact that it contains water is sufficient to attract a large number of birds and other wildlife. Each pond or stream acts as an oasis, and it is probable that at one time or another every species of birds within the surrounding territory can be seen near the water. Recognizing this fact, the bird list on this page includes only those species that are especially attracted to, or in some way directly associated with, this type of fresh-water habitat. Because of the similarity and proximity of fresh-water marshes and swamps, the reader should consult the lists in Chapter 9 for possible additions to this one.

Land absorbs heat more rapidly than water. The sun warms the forest floor; the spring peepers and wood frogs awaken from hibernation beneath their leafy covering. They head toward the pond for courtship and breeding. The night sleighbell chorus of the spring peepers signals the return of other creatures to the pond, now astir with the sustenance of life.

A few male red-winged blackbirds settle in the sedges along the edge of the pond, but the majority of the great flock continues toward the marsh. Here they will rest and feed on insects and last year’s seeds. Some will stay to claim nesting territories, but most of them will continue northward. The flock will thin as additional territories are claimed in marshes, meadows, and fields northward into Canada. Although the nesting locations are selected early, another two weeks or so will pass before the females arrive.

Other birds follow the receding ice line. A family group of Canada geese break their V formation and descend toward the pond. As they land, their broad webbed feet plow the surface momentarily, acting as brakes to slow their forward speed; with an accompanying back motion of the wings, the geese settle gently upon the water. Canada geese mate for life, and their social ties are quite close. Family groups stay together except during the nesting season, when they spread out over a region with rather definite boundaries. The geese in the pond feed on the roots of various aquatic plants. But they are restless; the call of the northland must be answered. Amid much clattering and honking, the flock is airborne once again. There is considerable calling and shifting of positions as they gain altitude and direction. But, as the fading sun tinges the western sky, the long V lances the northern horizon.

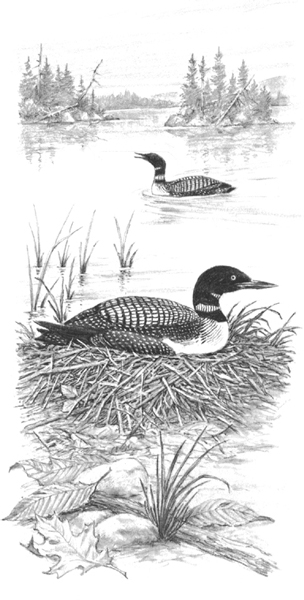

Out in the middle of the pond, a large bird is silhouetted against the glimmering water. It sits low in the water like a heavily laden freighter; it is a common loon. And on the far side of the pond, a pair of pied-billed grebes bob on the wind-blown ripples like a couple of corks. The loon has been on the pond for two days. It must be sure the ice is out and the winter storms are past before it ventures too far north; it cannot take off from land. The grebes, too, will spend several days on the pond, for they are strictly aquatic, also.

Here are some helpful facts to note when watching loons and grebes:

• Loons are larger than ducks, but sit lower in the water. Grebes are smaller than ducks, but sit higher in the water.

• Loons have thick necks and heavy, pointed bills. The necks of grebes are long and thin; the bills are pointed, but are not so heavy.

• Loons and grebes are chiefly fish eaters, and both are expert divers. They both have the ability to gradually sink out of sight by expelling air from within their bodies and from beneath their feathers.

• Loons and grebes need long, running takeoffs across the water to become airborne. When endangered, they dive rather than take flight. Either can swim at periscope depth with just their heads above the water.

• The feet of both families are placed far back on their bodies. The loons’ feet are webbed and used as propellers when swimming; the grebes’ toes are individually webbed, and they, too, are used for swimming. They flare open to give push to the backstroke and close to reduce resistance on the forward stroke.

• The common loon and the pied-billed grebe are the species of their respective families most likely to be seen on eastern fresh-water ponds.

• The common loon has a dark, glossy head and neck. It wears a necklace of white.

• The red-throated loon is seen occasionally on ponds, but is observed most often along the coast in winter.

• The pied-billed grebe has a chickenlike bill with a definite pied marking across it.

• The horned and the red-necked are the two other species of grebes likely to be found on eastern ponds.

With warmer and longer days, the pulse of life surges everywhere about the pond. The willows, alders, aspens, and birches are shrouded in a misty profusion of catkins, and the swamp maples are festooned in the reddest of reds. Pollen drifts through the air, consummating the wonder of pollination; it settles on the water and gathers in floating rafts along the pond’s edge. The pond is encircled with the pale greens of the spring’s new growth. This verdurous carpet is accented by the designs of deep-blue violets, the white of bloodroots, the pink of spring beauties, and the pale lavender shadings of mertensia.

Within the pond, the long period of dormancy has ended for all creatures. Even the lethargic bullfrog has wriggled free of the mud and has taken its place along the edge of the pond. Bugs, beetles, spiders, worms, crustacea, nymphs, larvae, and eggs are present in many forms and astounding numbers. The night chorus is now a mixture of loud, discordant croaks and trills. Frogs and toads by the hundreds have found their way to the pond to mate and lay their eggs. The pond is so full of life that if it all survived, the pond could not hold the massive bulk. But this will not happen, for the physical and biological factors involved in nature’s plan of survival will assure that only a sufficient number of individuals necessary to maintain a balanced environment will survive.

Above the pond, grackles wend their way northward in noisy flocks. Turkey vultures circle, looking for the first casualties of spring, and from beyond the trees comes the “kee-yer, kee-yer” of the red-shouldered hawk. A flock of robins progresses through the trees and shrubbery in a constantly moving wave; they eat hurriedly as they travel. Tree swallows fly low over the pond in loosely scattered flocks. Their flight is so erratic one wonders how many miles they actually travel in reaching their northern destination. Each day and night brings additional species to the pond; some will stay, but for others, home is still far to the north. As the great northward movement wanes, birds about the pond are already busy with the activities necessary to propagate their own kind. The herons have returned and stalk along the shallow edges. Secretively, the bitterns thread their way through the reeds and cattails; the coots squabble and chase each other all over the pond. The ducks have paired and seek nesting sites. Sandpipers and killdeers patter along the shoreline, and overhead the osprey watches for surface-feeding fish. The yellow warbler has returned to the willows, and the loud “tweet tweet” of the prothonotary warbler resounds from the wet bottomlands. Now, the great surfeit of life and energy in the pond will be harvested. There is purpose in abundance.

Much of the life within the pond gathers in the warm, shallow water of the edges. Minnows, frogs, tadpoles, reptiles, shellfish, and aquatic insects are there in great numbers. It is the season of plenty, and for the wading herons, hunting is easy. Although several species of herons depend upon the same basic food supply, there is little competition. Each species is adapted to a slightly different niche in the pond habitat. The green heron is small and comparatively short-legged; it still-hunts in the shallowest water. The little blue heron is an active feeder with a preference for crayfish, frogs, and insects. The Louisiana heron is also quite active when feeding, but it has an exceptionally long neck and bill, and is an expert at spearing fish. The longer legs of the great blue heron permit it to hunt in the deeper waters. The herons have large, slightly webbed feet, which keep them from sinking in the soft mud.1

Masses of frog eggs cling to the submerged plant stems in gelatinous globs. Millions of tiny black specks swell with the expansion of life therein, but nature decrees that only enough shall survive to replace the casualties of the season. The pond ducks are the first check on this potential explosion of life; they consume quantities of this rich food. But thousands of eggs reach the intermediate tadpole stage only to be preyed upon by the herons, reptiles, raccoons, and other shoreline marauders. The long siege in the cold water has ended for the dragonfly nymphs. They climb from the water on the stems of plants, and the miracle of transformation into adulthood begins in the warm rays of the sun. Hundreds will succumb to the patiently watching shore birds and other pondside creatures; others will fly away on transparent wings. But even for them, the incessant pursuit has not ended: they must escape such dangers as the instantaneous flick of a frog’s tongue or the sudden swoop of a hovering sparrow hawk.

Along the downwind shore of the pond, a pair of spotted sandpipers feed at the water’s edge; the pond has trapped a variety of insects which float ashore on the crest of gentle waves. The sandpipers walk slowly and deliberately with a teetering motion, now in the water, now out, picking up insects as they go. A dead fish has floated ashore and attracted a great many flies. The “teeter-tails” now employ a new technique: the teetering is stopped; the head is lowered and pointed forward so that it blends with the mottled background of the body. They stalk their prey and stand motionless until the flies land. With one quick peck of the sandpiper’s bill, an unsuspecting fly is captured. The spotteds will nest on the ground near the water, perhaps on the back edge of a gravel bar, or in the thin grass beyond the water’s reach.

The eastern side of the pond is wooded. From the dry upland woods, the land slopes almost imperceptibly to the water line. During the time of high water, this area serves as a flood plain for the pond; when the water is low, wide mud flats are exposed. Black willows and alders are the dominant trees near the water. The ground is mud-caked and littered with flood debris. Along the back edge of the flood plain, the willows and alders give way to maples, gums, swamp white oaks, and finally to the mixed hardwoods of the dry upland. To this wet, shadowy, and singularly odoriferous niche within the pond’s total environment comes the diminutive golden bird of the wetlands: the prothonotary warbler.

At first, the song is heard: a loud, clear “tweet tweet tweet” without any inflections. One might confuse the song with that of the solitary sandpiper, but the solitary departed the pond days ago and now sings along the lakes in the Canadian wilderness. The coloring of the prothonotary warbler is so distinctive that the bird is easily recognized: a deep yellow (almost orange) head and breast, and gray wings. It is the only cavity-nesting warbler in the East.

The male arrives first and claims his territory by stuffing tree cavities and old woodpecker holes with moss. When the female arrives, she selects the nesting site (frequently in a willow stub 5 or 10 feet above the water) and does most of the work, lining the nest with rootlets, strips of bark, leaves, or whatever soft material happens to be nearby. Like other warblers, the prothonotary is chiefly insectivorous. It feeds low among shrubs, fallen trees, driftwood, and other flood debris.

The yellow warbler also nests in the willows, but it is not so inherently bound to a specific type of habitat. Here it is reasonably free from its perennial nemesis, the cowbird, because the red-wings patrol the pond’s edges with a vengeance against these parasitic intruders.

Swallows come to the pond each day. They fly low over the water, and occasionally they skim the surface for a drink on the wing. The tree swallow is recognized by its dark back that reflects glints of metallic green. A number of them nest in abandoned woodpecker holes near the pond. The bank swallow and the rough-winged swallow are both brown above. The bank swallow has a white throat and sports a brown breast band; the rough-winged is more modestly garbed with a dusky throat.

An osprey hovers above the pond. With partially folded wings, it dives into the water and seizes a spawning blue-gill in its talons. The osprey shakes itself free of water, turns the fish head first to reduce wind drag, and flies to the great nest of sticks in a dead oak at the far end of the pond. The act has been one of frustration; the osprey’s long vigil for a mate has gone unrewarded. Nor will it be rewarded. This lone bird is symbolic of the tragic ending of a great drama. Man has poisoned the land and the water—the final curtain is closing.

There are many plants that grow in and around the pond. Some are submerged varieties such as coontail, musk-grasses, watermilfoils, and pondweeds. The duckweeds float freely; the leafy plants of water lilies and cow lilies float, but are rooted in the mucky bottom. Many plants emerge above the water; these include pickerelweed, rice cutgrass, wild rice, bulrushes, spikerushes, and reeds. Wild millet, chufa, and smartweeds abound on the previously flooded flats. These plants serve a number of purposes in the pond community. They protect the shoreline by breaking the eroding force of waves; they provide various insects and small mammals with a means of getting in and out of the pond; they provide cover and shelter; and perhaps most important of all, they are the chief source of food for a variety of pond ducks.

The number and species of ducks attracted to any one pond, lake, or stream will be influenced by the geographical location and the physical characteristics of that particular body of water. Black ducks and mallards may be content to nest about a pond in the open, but the wood ducks, goldeneyes, and buffleheads prefer woodland ponds. The mergansers like the clear water of northern woodland streams and rivers.

The greatest concentrations of pond ducks are in the central part of our country, but most species can be found in considerable numbers throughout the East. True pond ducks feed on the surface. Their food is chiefly vegetable, but it does include some animal matter such as mollusks, insects, and frog eggs. They feed by skimming the surface with their broad bills, by reaching beneath the surface, and where the water is deep, by tipping up—head submerged, tail straight up, and feet paddling the water. Pond ducks float high in the water, and they can “jump” directly into the air without any preliminary takeoff run. They are a gregarious lot and travel about in flocks except when nesting.

The list on the facing page includes species other than those normally classified as pond ducks. It is composed of those species that can be observed about ponds or streams at one time of the year or another.

The cool clear-running water of a woodland stream has a special fascination for wildlife and man. A stream incorporates movement, sound, and beauty; it is a means of transportation and a source of food. It is difficult to classify as a special type of habitat, for it often supports many of the same plant and animal species that are found in other fresh-water communities. Also, the characteristics of each stream vary according to location, terrain, and source of water. But each stream has some features that make it especially attractive to certain species of birds.

Ecologists tend to classify a stream and its tributaries as an independent evolutionary unit. Through distribution by water, plants and animals occupy every suitable niche along the full length of the stream. For example, the black willow is one of the most common trees along our eastern streams. The cottony down, to which the seeds are attached, floats upon the water, and during the periods of ice-out and flooding, many stems and twigs are broken off and carried downstream to be replanted in mud, sand, and debris. You will find the willows most plentiful at bends in the stream and in the flooded lowlands—places where the seeds and twigs are washed from the main current and find a natural anchorage. These willow bottoms are attractive to the prothonotary warbler and the yellow warbler. Species such as the woodpeckers, tree swallows, and wood ducks will occupy cavities in the soft wood of mature trees.

There are two methods of watching birds along a stream: you can sit on a cushion of moss, lean back against a stalwart tree, and watch the activities within view; or you can follow the stream. Depending somewhat on the stream, one method may be just as rewarding as the other. Personally, I prefer to follow the stream, especially if I can supplement my birding equipment with a pair of boots or waders and a fly rod. Some of my most exciting birding has been while fishing. They are complementary activities that supplement each other beautifully, and I recommend the combination with fervor. The last duck hawk I saw was along a trout stream in Maine; it flashed around a bend and passed so close I could almost touch it with my fly rod. Streams have led me past great colonies of bank swallows, burrows of kingfishers, and nests of spotted sandpipers. Perhaps the most exciting discovery of all—a once-in-a-lifetime experience—happened while I was fishing French Creek near the little village of Knauertown, Pennsylvania. I was following the meandering stream through Lytle’s meadow when I discovered a number of chimney swifts using a large, hollow tree stub as their nesting site. Your discoveries will undoubtedly be different, but around each bend, a new adventure awaits you—and perhaps a brook trout will rise to your drifting fly.

The loud, rattling call of the belted kingfisher is a common sound along our eastern streams and ponds. The metallic-sounding clatter is uttered often, as the bird flies low over the water, and just after landing on, or departing from, a favorite fishing perch. Mostly, the call is given as a warning against possible intrusion by other members of the species; the kingfisher will not tolerate poaching on its selected territory.

The belted kingfisher is the only member of its family to be found in the East. It hunts from a perch over the stream, or by hovering in midair. When a fish is sighted, the kingfisher dives into the water like a tern and captures the fish in its long, heavy beak. If you watch the kingfisher after such a capture, you will see it fly to a convenient perch and then rap the fish against the limb several times. This stuns or kills the fish so that it can be more easily maneuvered into a head-first position for swallowing. The nest of the kingfisher is placed at the end of a burrow, which it digs in the side of a steep, clean bank. The selected bank is usually quite sandy, but it must be compact enough to prevent the burrow from collapsing. The burrow is usually 4 or 5 feet long and about 4 inches in diameter. It is found most often along the bank of a stream, but if the stream banks are too low, or not of the right soil consistency, the kingfisher will nest inland.

The belted kingfisher is easily recognized. Slightly larger than a robin, it has a large, ragged, blue-gray crest and a heavy bill. Both sexes are blue-gray above and white underneath; the male has a single, blue-gray chest band, but the female is a bit more colorful with two chest bands, one blue-gray and the other rusty brown.

Bank swallows also nest in self-dug burrows, often along the bank of a stream, but their requirements for a suitable nesting site are more specific than those of the kingfisher. They are colony-nesting birds, and the bank selected must be large enough to hold a number of burrows. It must be quite high, vertical, and free of vegetation. Also, it must be of the right sand and gravel consistency to permit digging, yet avoid collapse. For these reasons, bank swallows are most abundant in areas of glacial moraine deposits.

Every stream has its spotted sandpipers. They flutter from rock to rock, or for short distances along the shorelines, on stiff, downcurved wings. The clear, loud call of “peet-weet, peet-weet” is very distinctive. One can easily see how this sandpiper gets its name; in breeding plumage, it is the only member of its family with a spotted (rather than streaked) breast.

Certain species of birds are attracted to streams with specific physical characteristics. Small, shaded, woodland streams attract the waterthrushes. Phoebes will nest on stone ledges and under bridges. Black ducks may be at home in slow, sluggish streams, but the mergansers prefer the cool, clear waters of northern trout and salmon streams, where they feed on the small fry, often to the consternation of fishermen.

Regardless of where your favorite stream may be, it is undoubtedly an ideal place to watch birds. In addition to the water birds, warblers and vireos sing from the treetops; the calls of thrushes and ovenbirds echo from the adjacent woodlands; ruby-throated hummingbirds feed amid the jewelweeds and cardinal flowers; and dozens of species come to the stream to drink and bathe. The lure of a stream attracts many birds and is specially rewarding for those who come to watch them.

1 For additional information on the identification and habits of herons, see Chapter 10.