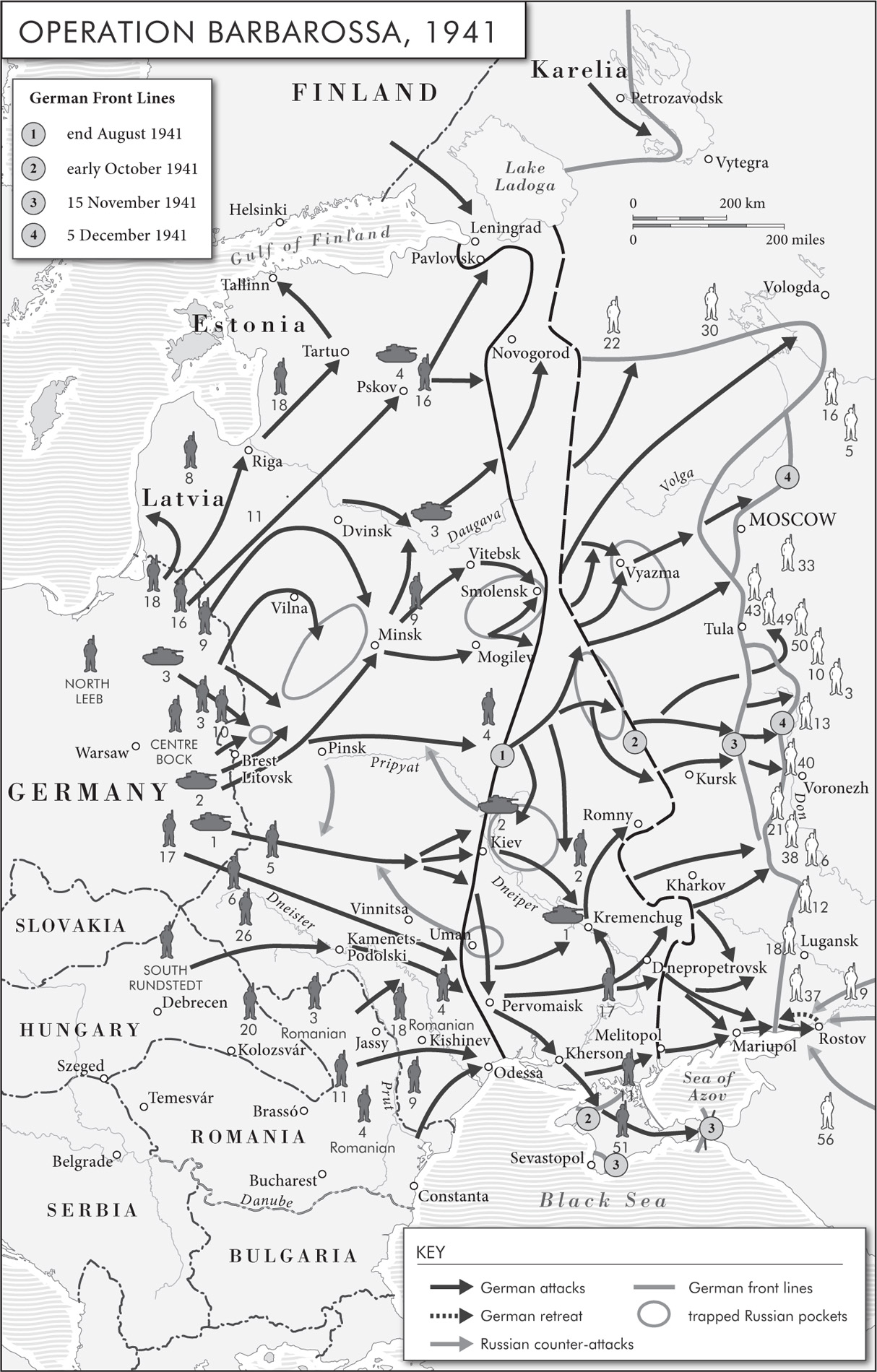

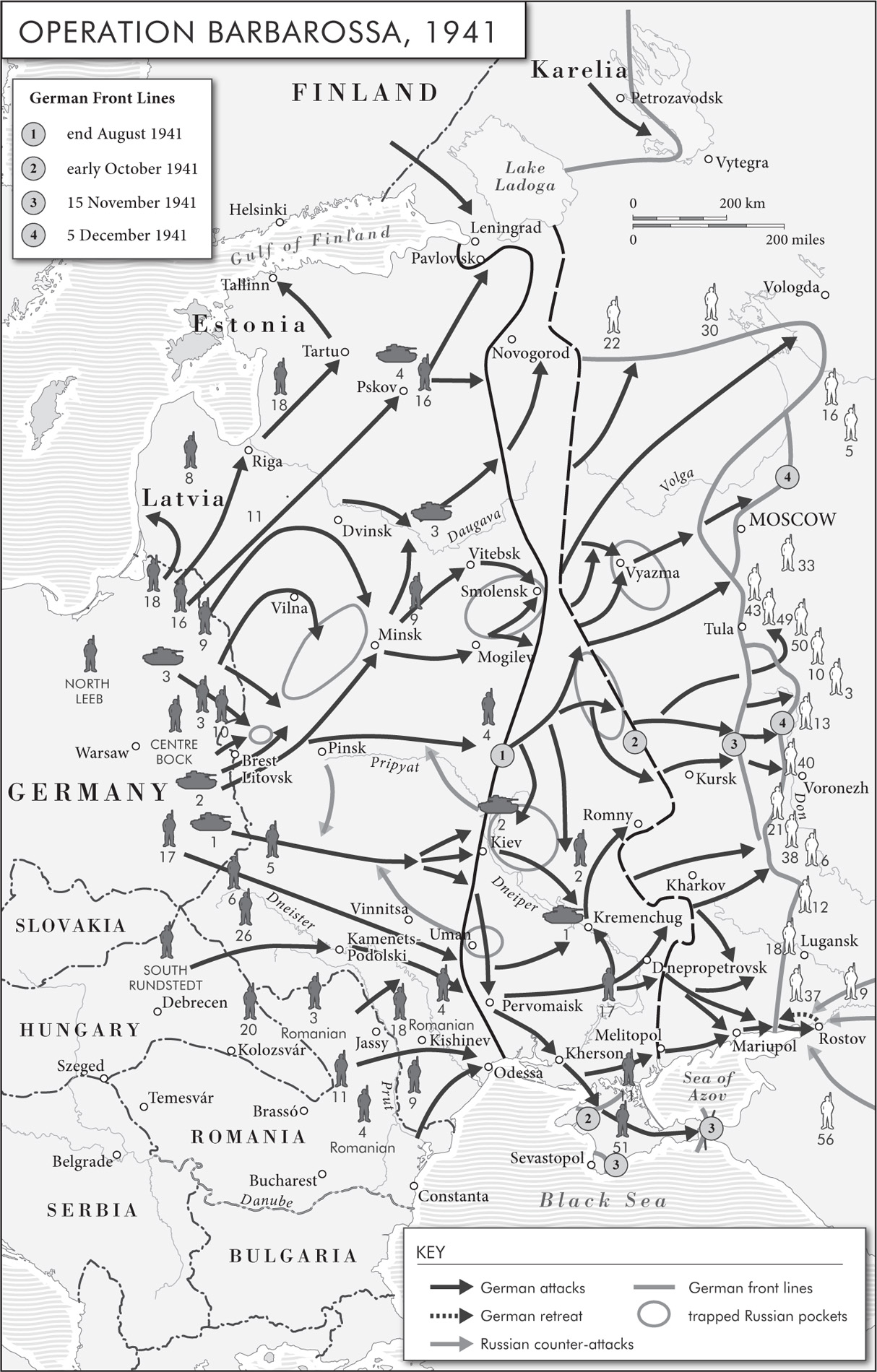

ON SUNDAY, 22 JUNE at 3.30 a.m., German summertime, BARBAROSSA was finally launched. Guns opened up as some 3,600,000 men, more than 3,500 panzers and 2,700 aircraft began streaming across the Soviet border of former Poland along a 1,200-mile front. To the far north, two Finnish armies were also on the move, joining forces with Germany against an enemy that had invaded their country back in 1939; this was their chance for revenge. Now they were heading across Karelia towards Leningrad and supported by 97,000 German mountain troops from Norway. Prior to this massive movement of armies, 800 ‘Brandenburgers’ – special forces disguised as Russians – had crossed into Soviet territory and blown up power stations, cut telegraph wires and other communications, so that at the moment BARBAROSSA began, telephone lines up to 30 miles inside the border had been severed. Soviet security in the border area had proved extraordinarily lax; this augured well for the Germans.

Much to his frustration, however, and despite his proven track record, Oberst Balck was not part of this first wave of German panzer units in the attack on the Soviet Union. To his chagrin, he was called to Berlin where he was to help the beleaguered General Adolf von Schell, the General Plenipotentiary of Motor Vehicles at the OKW, and General Friedrich Fromm, who commanded the Ersatzheer, or Reserve Army, which co-ordinated all personnel from training to replacements sent to the front.

In many ways, however, attempting to streamline military motor production was a greater challenge than fighting the Red Army. Ever since 1938, General von Schell had been valiantly trying to make German motor production more efficient and to make the Army increasingly mechanized. The trouble was that right up to the war and beyond, the German motor industry was both small and disparate, made up of numerous independent companies. Compared with Britain, France – which had been Europe’s leading motor-vehicle producer before the war – or especially the United States, Germany had been, and remained, way behind.

This could not be rectified overnight, particularly in a country so short of resources such as oil and even steel; there were simply too many competing areas, such as ships and aircraft. Nor were there enough factories, or garages, or enough spare parts. Lots of small companies making lots of different models was inherently inefficient and meant large-scale mass production was impossible. Yet Hitler wanted his armies to be increasingly mechanized. It had been von Schell’s task to make possible the impossible. It had been a Herculean one, and he had achieved a great deal, all things considered, but the string of victories had, in many ways, only added to the problems. Part of the booty of war had been vast numbers of captured vehicles, but these were all different too and rarely came with spares. Von Schell had just managed to partially streamline vehicle production in Germany only to be saddled with a whole load more different types.

Repeatedly, he had been told how important it was that the Army have as many vehicles as possible for BARBAROSSA, yet further compounding the challenge had been the campaigns in the Balkans, Greece and North Africa, all of which had been conducted over difficult terrain with few and very poor roads. It was also clear that the wear and tear on vehicles in the Soviet Union was going to be considerable, as it was a country with few properly metalled roads.

Balck arrived in Berlin a few days after BARBAROSSA had begun, only to learn that his young son, a platoon commander, had already been killed in the fighting. Reeling from this blow, he was relieved to have so much work on his hands to take his mind off his family’s loss. The task ahead of him was truly daunting, however, because as matters stood there was not a hope of making the Wehrmacht more mechanized – not with the inevitable strain that would be placed on vehicles operating somewhere as vast and underdeveloped as the Soviet Union, and while vehicle production was still stuttering. Somehow, some way, he was to try to conserve or find up to 100,000 vehicles. It was a lot to expect.

Although BARBAROSSA had an ideological dimension that had been absent from the early campaigns, it was none the less based on the age-old German principles of war. It was to be Bewegungskrieg on a grand scale – that is, heavily front-loaded, with the aim of smashing and annihilating the Red Army swiftly in a gargantuan Kesselschlacht, or encirclement, as close as possible to the western edge of the Soviet Empire in order to keep supply lines and distances generally as short as possible. In other words, the plan was, in essence, the same plan Prussian and then German armies had used for centuries.

To begin with, BARBAROSSA appeared to be going spectacularly well for the Germans, helped by Stalin’s curious refusal to accept any warning signs of an imminent attack. The Soviet leader had been in denial about the build-up of troops near the border in former Poland, as well as intensive German road and airfield building, repeated infringements of their air space, and the mass of intelligence that all seemed to point in one direction; BARBAROSSA had been the world’s worst-kept secret. Despite these indications, however, it was less tactical surprise that caught out the Red Army than overwhelming force at the Schwerpunkt – the point of attack. Sweeping across a 500-mile front, all three Army Groups gouged huge chunks out of the Soviet Union in the first fortnight alone. In the north, Feldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb’s Army Group North overran the Baltic States; in the centre, Generaloberst Fedor von Bock used the panzers of Army Group Centre to charge across Poland and envelop a massive pocket around Białystok; in the south, Feldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt faced stiff resistance, but Army Group South still made huge strides. By 13 July, as the ‘frontier battles’ phase ended, the Germans had advanced between 300 and 600 kilometres and had killed, wounded or captured 589,537 – that is, some 44,000 Red Army troops per day, or the equivalent of three divisions. They had also destroyed 6,857 Soviet aircraft, mostly on the ground.

After giving himself a brief resumé of the situation, on 3 July Halder wrote in his diary, ‘It is thus probably no overstatement to say that the Russian Campaign has been won in the space of two weeks.’1 There then came a caveat: ‘The sheer geographical vastness of the country and the stubbornness of the resistance, which is carried on with all means, will claim our efforts for many more weeks to come.’

By the end of July, German advances were such that their drive looked as unstoppable as it had done in Poland, Norway, France and the Balkans. Guderian had taken Smolensk and now his forces were pushing southwards, while General Hermann Hoth’s to the north looked like they would encircle three Soviet armies. Further to the north, German forces were sweeping towards Leningrad. Victory appeared to be within their grasp. It was not, however – not by any means; rather, Red Army forces were starting to coalesce and even counter-attack. And it was at this moment that the German wheels, literally, began to come off the campaign.

General Walter Warlimont and his Section L of the Operations Staff at the OKW had moved to the field headquarters near Rastenburg in East Prussia, which was called HQ Area 2 but known as the ‘Wolf’s Lair’. It was a mixture of wooden huts and gaily painted underground concrete catacombs surrounded by high barbed wire, with an old and now appropriated country inn at its centre. Warlimont, who felt quite claustrophobic in his underground double room, soon moved into the inn, which became an unofficial Officers’ Mess. From HQ Area 2, Warlimont was able to follow the growing frustrations of both Halder and the OKH General Staff and his own team at Section L as Hitler once again began interfering with the day-to-day conduct of operations. For men such as Halder and Warlimont, hugely experienced in staff work and fully conscious of the enormous task facing the Wehrmacht, it was painfully frustrating to witness the Führer’s glaringly poor, self-taught generalship and incapacity to accept well-tested military principles.

Hitler had already insisted on 19 July that Leningrad in the north and the Ukraine to the south were the priorities and that Army Group Centre was to hand over its two panzer groups once the huge pocket around Smolensk had been crushed. Moscow, he ordered, would be bombed by the Luftwaffe, as though that were enough to bring the Soviet capital to its knees, and even though the Air Force’s track record when operating unilaterally was hardly one to inspire much confidence.

Then four days later the Führer issued a supplementary order, which demanded even further objectives in the south and insisted that the Luftwaffe then turn to support the drive of the Finnish armies. ‘This,’ he declared, ‘will also reduce the temptation for England to intervene in the fighting along the Arctic coast.’2 How on earth Hitler thought Britain would quickly send a task force to the Arctic is not clear, but there were obviously far more important targets for the Luftwaffe. As it was, Moscow was never bombed by anything close to a massed raid.

A further directive appeared on 30 July, with yet another amendment on 12 August, as Hitler obsessed about his flanks and worried about the slowing pace in the south. The trouble was, just as had been feared by the logisticians, the Germans had reached the limits of their lines of supply. The speed of advance had taken a terrible toll on German mechanization. Günther Sack, for example, a young anti-aircraft gunner and now attached to 9th Division with von Kleist in Army Group South, suffered a puncture on their gun carriage, which held them up. On 15 July, their truck broke down with a seized engine. By the time they had a replacement, the rest of their battery was way ahead. Then the trailer broke again and had to spend several days in the divisional workshop that had hastily been set up. Not until 26 July did they finally catch up. Sack’s experience was a common one.

Meanwhile, the Panzergruppen of Generals Guderian and Hoth had smashed Smolensk only by another furious drive that pushed their men and machines to the limits of their capabilities. When that ran out of steam, they were forced to dig in and fight off a string of furious counter-attacks. This was where BARBAROSSA differed from earlier campaigns. The Red Army appeared to have collapsed – but it had not entirely. The German way of war was to knock the enemy off balance, then drive home the killer punch. The Soviet Army had been knocked spectacularly off balance, but was already beginning to get back on its feet again as a further 5 million men were called up. No fewer than seventeen armies were thrown into the counter-attacks opposite Army Group Centre; at this time, Britain barely had one.

Hans von Luck was now a reluctant staff officer with 7. Panzerdivision HQ, part of Army Group Centre. ‘We very soon had to accustom ourselves,’ he wrote, ‘to her almost inexhaustible masses of land forces, tanks, and artillery.’3 The Soviet Union was not France. It had enormous geographical reach with no English Channel or Atlantic Ocean limiting any retreat, vast amounts of manpower and, unlike the Western democracies, it was a totalitarian state whose leaders had not a single humanitarian care for the lives of their men.

In Britain, the reaction to the German invasion of the Soviet Union was mixed. On the one hand, it was good to know that any further plans for an invasion of Britain must have been shelved for the foreseeable future and that the USSR was now bearing the brunt of Hitler’s military ambitions. On the other hand, the prospect of a German victory was terrifying to say the least; British war leaders were every bit as aware as those of Germany that the Soviet Union was a giant expanse containing critical resources of food, fuel, manpower and industrial potential.

British mistrust of Communism and the new Russian order had ensured they had missed the diplomatic boat back in the months leading up to the outbreak of war. There could be no more political reticence, however. Realpolitik needed to trump political sensitiveness. ‘My enemy’s enemy is my friend’ was a mantra that had to be acknowledged and acted upon swiftly; the fact that the British king’s relatives had been murdered by the Soviets, or that the Prime Minister had been among the most eager of British politicians to try to quell Bolshevism, or that the totalitarian control of the Communist state was uncomfortably similar to the totalitarian control of the Nazis, had to be put to one side. Yes, ridding the world of Hitler and the Nazis was Britain’s strategic end-goal, but they had to ensure the safety of their own sovereignty first.

Three weeks after BARBAROSSA was launched, on 12 July 1941 an agreement was signed between Britain and the USSR to provide ‘help and support of any kind in the present war against Nazi Germany.’4 There was most definitely a certain degree of gritted teeth from both parties as they signed the agreement, but what the Kremlin was asking for in the short term was supplies: tanks, aircraft, trucks, uniforms – anything, frankly, that might help the Red Army. Britain, of course, had innumerable demands herself for such war materiel, but it was a question of priorities. Right now, in the second week of July, Soviet prospects did not look good; they needed help and urgently. In any case, it was far better to send tanks and aircraft – which were, after all, only machines – for Red Army troops to be killed and wounded in rather than British. The British strategy of ‘steel not flesh’ could be applied to sending aid to the Soviet Union too. Even so, getting these supplies there would not only place an extra burden on the already overstretched Navy and Merchant Navy, it would inevitably cost British lives too – just not as many lives as would be lost if the Soviet Union was defeated.

The United States, meanwhile, was taking this approach a step further by sending aid not only to Britain but now also to the Soviet Union; far better that British and Soviet servicemen face the fire than Americans. At any rate, it was clear to Roosevelt that the US, like Britain, must hurry to the USSR’s aid pretty darn quickly, and so he sent his friend and most trusted confidant, Harry Hopkins, first to confer with the British once more and then to fly on to Moscow.

It was a frenetic few weeks for the US President’s special envoy. Although Hopkins was only fifty years old, illness had plagued him for years and travel never did much for his precarious health – especially not long-distance travel in a succession of American heavy bombers and flying boats – but he none the less had reached Britain and then London safely, renewed his growing friendship with Churchill, attended a War Cabinet meeting – the first foreigner ever to do so – and arranged for Churchill, Roosevelt and the Chiefs of Staff to meet at Placentia Bay in Newfoundland on 9 August.

While he was in London, Hopkins also met Ivan Maisky, the Soviet Ambassador. During their conversations it became clear to both men that a visit to Moscow would be of enormous benefit. By meeting Stalin, Hopkins could see for himself exactly what Soviet intentions were and precisely what they most needed and hoped for from the United States. Stalin would also be able to draw reassurance from seeing the President’s special envoy in person.

On Sunday evening, 27 July, Hopkins made a broadcast on the BBC from Chequers. ‘I did not come from America alone,’ he told his listeners.5 ‘I came in a bomber plane, and with me were twenty other bombers made in America.’ He also made it clear that Roosevelt was as one with Churchill in his determination ‘to break the ruthless power of that sinful psychopath in Berlin.’ Afterwards, Churchill and Hopkins talked together in the garden; it was around ten o’clock but still light, and the PM spoke of the importance of Russia now being in the fight and the aid Britain planned to send. Hopkins asked if he could repeat this to Stalin.

‘Tell him,’ Churchill said, ‘that Britain has but one ambition today, but one desire – to crush Hitler.6 Tell him that he can depend upon us.’

Hopkins flew to the Soviet Union the next day. It was an exhausting trip for him, but a success. Once again, his unerring ability to charm people with whom, on one level, he had very little in common won him renewed admiration. In two lengthy meetings with Stalin he was able to discern a sense of the Soviet leader’s determination to keep fighting and to convey the earnestness of America’s willingness to help. Hopkins had been careful not to patronize. Equally, he had been impressed by Stalin’s list of requirements. The fact that aluminium was high on his list, for example, suggested the Soviet leader was expecting a long war, not imminent defeat. These were potentially fraught – even surreal – circumstances between two ideologically and politically diverse men. A deft touch of diplomacy was needed from both parties. Both provided it.

Hopkins flew back to Britain in time to join the Prime Minister and the British Chiefs of Staff for the trip across the Atlantic on the battleship HMS Prince of Wales. What a tasty target this giant ship would have been for any skulking U-boat – yet thanks to decrypted German Enigma traffic, known as ‘Ultra’, to high-frequency direction finding – HF/DF, or ‘Huff-Duff’ – and to the 29-knot speed of the ship, it was about as safe a means of travel as any in the summer of 1941. At any rate, they reached Placentia Bay untroubled and made their rendezvous with the Americans on the morning of Saturday, 9 August.

For Churchill this was a big moment. He had been striving to draw ever-closer co-operation from the United States since his time at the Admiralty and was equally eager to forge a sense of common purpose and even friendship. ‘He is excited as a schoolboy on the last day of the term,’ noted Churchill’s secretary Jock Colville before the PM left.7 Certainly he was in his element on board the Prince of Wales – he was the nation’s war leader crossing the Atlantic battleground on a mighty warship, sailors and senior commanders all around him. He found it thrilling.

There was a dinner and discussions on the USS Augusta, then, the following day, a church service and lunch on the Prince of Wales. Finally, on Monday 11th, by which time Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Production and close confidant of the Prime Minister, had joined them, Churchill and Roosevelt had a more intimate, less formal lunch. Much of the discussion was about the growing aggression of Japan, but it was also reaffirmed that if the US entered the war then together with Britain they would focus on the defeat of Nazi Germany before Imperial Japan. US naval participation in the Battle of the Atlantic was also confirmed again, and it was agreed there would be a three-way conference between Britain, the US and the Soviet Union in September, while a pledge of aims, which became known as the Atlantic Charter, was also drawn up and signed.

In it, Churchill and Roosevelt declared to the world eight common principles. They sought ‘no aggrandisement, territorial or other’.8 They also respected the rights of all peoples ‘to choose the form of government under which they will live’. The sixth point dealt directly with Germany: ‘after the final destruction of Nazi tyranny, they hope to see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want.’ It was heady, utopian stuff, and back in Britain caused some embarrassment for Churchill; India, for example, had been on the cusp of independence before the war, but there were many there who believed they were not being given the chance to choose their own government. The Atlantic Charter hardly endorsed empire.

None the less, the charter was significant and placed the war firmly on a moral footing in the eyes of Britain and the United States. This alone set the current conflict apart from those that had come before.

Just as importantly, Roosevelt and Churchill had finally had the chance to meet one another properly and, while neither forgot that theirs was a professional relationship, they liked one another and got on well. Roosevelt was a head of state, Churchill was a chief minister – and there was a difference – but both were global military-politico leaders speaking the same language and with the same essential aims. The importance of this meeting in Placentia Bay has often been played down. It should not be.

While much of the Luftwaffe had been sent east, the burgeoning night-fighter force was continuing to do its best to combat the almost nightly RAF raids over occupied Europe. The night-fighters had been formed into XII. Fliegerkorps under Josef Kammhuber, who had been promoted to general the previous summer and made Inspector-General of Night-Fighters.

In July, Helmut Lent, only twenty-three but already a veteran of Poland, Norway and the Battle of Britain, was given command of 4/NJG1 based at Leeuwarden in Holland. With twenty-seven victories to its name, it was, by some distance, the most successful night-fighter unit and already contained several aces, including the aristocratic Leutnant Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld. Its reputation, however, rested not only on its young aces, but also on the part it was playing in developing night-fighter tactics. As in Britain, the Germans had been trying to harness new technology to interception techniques.

By the time Lent took over 4/NJG1, Kammhuber had developed a defensive line in which a system of controlled sectors, equipped with radar and searchlights, were linked to a night-fighter unit. Each sector was known as a Himmelbett zone of about 20 miles by 15 and included a Freya and later two Würzburg radar sets, a ‘master’ radar-guided searchlight, a number of manually controlled searchlights, and had two night-fighters attached – one primary and one back-up. As an enemy bomber crossed into the range of the Würzburg, one radar set tracked it while the other followed the movement of the night-fighter patrolling that particular zone, or box. The zone’s controller then radioed interception vectors to the night-fighter and, once the attacker was close, his target was lit up by searchlights.

What was setting 4/NJG1 apart, however, was the determination of its pilots to be guided to their targets without the use of searchlights, which they considered unsatisfactory because of the glare and because of the evasive moves a trapped bomber would then make. They felt it was far better to trust one’s instruments and prowl up to a target without the enemy crew realizing. Dunkle Nachtjagd – dark night hunting, as it was known – of course, took huge skill.

Lent’s new command, he told his parents, was ‘fit and cheerful and safe in God’s hands’, and after familiarizing himself with a new Dornier 215 night-fighter, he wasted no time in getting flying.9 Within a week of joining his new Staffel he had shot down three enemy aircraft – no small achievement. ‘Last night my eighth kill went down,’ he wrote to them, ‘that is my fifteenth victory.10 I’m enormously pleased that I’ve been able to get off to such a good start in my new staffel.’

Back in the United States, the US Army was now preparing for war, and certainly the Atlantic Conference was a further step towards full involvement in the conflict. Stalin had kept pushing Hopkins, and Churchill continued to exert pressure, but while the Americans studiously refused to be drawn into any kind of discussion on the matter, it didn’t take a genius to see that it was increasingly a question of when, not if. In any case, to all intents and purposes, their Navy was already at war with Germany.

Certainly the US Army was now preparing for combat and growing in size too. The old pre-war atmosphere of easy laissez-faire had gone, replaced with a new sense of purpose and a determination at the very top to revolutionize the Army into an efficient, modern fighting machine. It was beginning to look different too.

Ever since the last war, the US Army had equipped its men with the standard round-rimmed Tommy helmet, as used by the British. A completely new design was now coming into service, however, known as the M1. This fitted comfortably over the head and covered much of the back of the neck and ears, but its liner was both more comfortable than the old helmet and a closer fit. It was ‘cleared for procurement’ on 7 May 1941 and it was recommended that ‘the item be given priority as essential.’11 It would take time for the changeover to be completed, but in keeping with the rapid rearmament programmes now under way, a variety of civilian firms would be involved in its manufacture, including, for example, the McCord Radiator Company of Detroit, who within a year would be producing no fewer than 400,000 M1 helmets per month.

New uniforms were entering service as well. The US Army had issued its men with a wool ‘OD’ – olive drab – service coat, which was similar to the field tunics worn by many nationalities; it was, in essence, a tunic with big pockets and brass buttons that came halfway down the thigh. By early 1940, however, General George C. Marshall, the Army Chief of Staff, felt it was time for a new look – one that reflected the largely civilian and modern army he hoped it would become, and one that provided both comfort and easy movement. A number of civilian windbreakers were examined, but none quite hit the mark, so Major-General J. K. Parsons, commanding the 5th Division, was given the task of overseeing the design, trials and eventual procurement of a new field jacket. ‘In deciding upon the garment to be recommended,’ he wrote to the Adjutant-General, ‘the needs of the Infantry soldier were given primary consideration.12 It was therefore decided that a suitable jacket to meet his needs must not only be warm and comfortable, but must be light in weight and have the minimum in bulkiness.’ This was much the same brief given the designers of the British Battledress, but in its consideration of comfort for the ordinary soldier, quite radical.

A design was drawn up and produced. Although it was olive drab in colour, it did look very like a civilian windcheater, with a centre zip-and-button combination, generous under the arms and coming down to just below the waist. General Parsons tested the jacket extensively using 400 of his men as guinea pigs. Any adjustments – such as taking the flaps off the side pockets – were due to the advice of the majority of these soldiers.

The Quartermaster General’s office still sent the design to Esquire magazine, who advised further on cloth and, inevitably, the look of the thing, which prompted a rather terse reply from General Parsons. ‘Esquire may be an authority on what a well dressed gentleman should wear,’ he wrote, ‘but a study of its comments and the design of the garment it submitted as a substitute shows plainly that it does not understand the purpose of the garment and is ignorant of the needs of the soldier in the field.’13 Someone else from behind a desk then suggested it was too short and in cold weather might cause kidney trouble. ‘All I can say,’ replied Parsons, ‘is most men have kidney trouble when in the presence of the enemy and it is fear not the length of the garment that causes it.’

The new M1941 field jacket, known, perhaps justifiably, as the ‘Parsons Jacket’, was duly adopted. Made of water-resistant cotton and lined with warm but lightweight wool, there was no other military jacket in the world that looked so casual or modern, nor one that had been designed and adopted with such thorough testing by those who would subsequently be wearing it in combat. As the US Army prepared for war, it was demonstrating a highly pragmatic but forward-thinking outlook – and, crucially, one that was not constrained by its military past.

Having snappy new uniforms in the pipeline was all well and good, but the men in this rapidly expanding Army had to be trained, and with suitable principles of doctrine at both the tactical and operational level. In Washington, GHQ had been renamed Army Ground Forces (AGF), and one of the up-and-coming officers in the US Army, Lieutenant-Colonel Mark Clark, had been promoted two jumps – and over a number of men who had been his senior – to Brigadier-General and Chief of Staff to General Leslie McNair, Chief of Staff at US General Headquarters. After long years in the 1930s barely progressing at all, the tall, 45-year-old Clark was suddenly going places.

McNair had asked Clark to prepare a series of large-scale military manoeuvres so that Army Ground Forces could test the soundness of their logistical doctrine and the men could live, sleep and operate as close to combat conditions as possible. The Louisiana Maneuvers that August were the fruits of Clark’s efforts and those of McNair’s staff at AGF, and marked the first time infantry, artillery and armour were placed on an exercise with air forces too, and in which the medical, signals and other support services were tested together. They were, in effect, a massive war game, in which the Second and Third Armies were pitted against one another.

Among those taking part were Tom and Henry ‘Dee’ Bowles, identical twins from Russellville, Alabama. They had just suffered a terrible blow, because in July they had received telegrams telling them their father was critically ill. At the time they had been carrying out amphibious training, not least because part of the AGF plans were amphibious invasions of Dakar and the Azores. Put ashore, they hitchhiked back to Russellville. ‘Daddy died on 31 July,’ said Henry.14 He had been just fifty-four. Both their parents had now gone.

They had returned in time for the manoeuvres, however, which, if anything, opened their eyes to how ill-prepared the US Army was for war. They were still wearing their old uniforms and wide-brimmed felt hats, and, although they had been issued with the new M1 Garand rifle, they noticed that many of those in the National Guard divisions were still using wooden rifles. Nor did they see any tanks, but, instead, trucks with logs sticking out the front in an effort to simulate armour. ‘You’d have planes flying over,’ said Henry, ‘dropping paper bags full of flour instead of bombs.’15

Another taking part was Sergeant Ralph B. Schaps, from Lastrup, Minnesota. Schaps was twenty years old and, although he had younger brothers and a sister, was, like the Bowles twins, effectively on his own in the world – his mother had died in 1937 and his father had been badly burned in a garage fire back in 1930 and had been in a nursing home ever since. While his siblings had been looked after by uncles and aunts, Ralph had largely managed to fend for himself, attending the Mechanics Arts High School in St Paul, from where he had graduated in 1939. While there, he had also joined the Minnesota National Guard, largely because it had meant being paid $24 every three months for just one three-hour training session per month and a two-week annual summer camp. It seemed like a fair deal. After graduating he had gone to work for his uncle in a garage in Austin, Minnesota, and so transferred to the National Guard there, which was Company H of the 2nd Battalion, 135th Regiment, 34th ‘Red Bull’ Division. Schaps had assumed that he would simply continue in the same vein – working in the garage and attending his monthly training sessions – but on 10 February 1941 his regiment had been activated and placed into the US Army for one year of training and service. Anyone who didn’t want to go full-time could leave with no questions asked, but Schaps had decided to stay. Placed in the 1st Platoon, Heavy Weapons Company, he was posted with the regiment to Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, where he was put through the non-commissioned officers course. Now an NCO with stripes on his sleeves, he had joined the Training Cadre. It was his job to help lick the new recruits into shape.

Everyone in the regiment took part in the manoeuvres, however. Also still kitted out in the old army leggings and Montana peak hats, Schaps and his fellow Minnesotans did not much like the swamps of Louisiana, with their bugs and mosquitoes, and they were resentful, too, that they were still using antiquated kit. ‘There was a lot of griping and bitching among the troops,’ noted Schaps.16 None the less, he thought the manoeuvres did them a lot of good. ‘We learned how to live and get along in the field, and that it was necessary to depend on and trust one another. We learned to get along with one another and work as a team.’

While invaluable lessons were being learned by the Army in Louisiana, the Air Forces were also expanding and preparing for war. On 21 June 1941, the Air Corps had been redesignated Army Air Forces (AAF), with General ‘Hap’ Arnold as chief, and with ‘Tooey’ Spaatz, now a Brigadier-General, as the first Chief of the Air Staff as well as continuing his role as Chief of Plans in what was now called the Air War Plans Division (AWPD). Although still part of the US Army, rather than an entirely independent service, the Air Forces did now have their own staff. None the less, this lack of complete autonomy threatened to come to the fore almost immediately, because on 9 July Roosevelt asked the Army and Navy to prepare a new revised estimation of requirements needed to defeat America’s potential enemies – that is, Imperial Japan and Germany. When Spaatz realized the Army were planning to submit air plans themselves, he asked Arnold to intervene, aware that the Army would view air requirements in terms of close tactical support for the ground forces.

Much to Spaatz’s relief, the Army War Plans Division accepted the argument that the Air War Plans Division should draw up their own appreciation of requirements. The result, prepared in just one week in early August, became the key document in the Army Air Forces’ preparations for war, outlining as it did their strategy for the use of air power as worked out by pre-war study and by observation during the Battle of Britain. The AWPD/1, as it became known, ranged well beyond what the Plans Division had been asked to provide. Key to this strategic vision was to wage a sustained strategic air offensive against Germany and Japan. As far as Germany was concerned, AWPD/1 outlined a sustained strategic air offensive in which industrial, civil and communications targets were identified. In fact, quite specific targets were included, such as power stations, aircraft factories, oil and other war production facilities. They also anticipated supporting a land invasion of occupied Europe. Another assumption was that bombing needed to be accurate and that the only way to do that was by attacking in daylight hours. This was a pre-war view and one that Spaatz had been determined to stick with following his experiences in Britain the previous summer. High-altitude, massed formations, heavy armour and armament, speed, and the sophistication of the pioneering and closely guarded Norden bombsight, which could measure an aircraft’s ground speed and direction as well as flight conditions, were seen as key elements that would ensure success. To achieve these ambitious goals, AWPD/1 called for the precise figures of 2,164,916 men and 63,467 aircraft, of which 4,300 were to be allocated for Britain.

At the time of AWPD/1, there were just 150,000 men in the Army Air Forces, so there was still a long way to go, but around the United States more and more men were undergoing flying training. The Air Forces were expanding, but there were simply not enough facilities or airfields to train the numbers needed for such a sudden increase, so some civilian flying schools were roped in to help. It was as part of these Government-backed civilian training schemes, for example, that Dale R. Deniston managed to get through Civilian Pilot Training. From Akron, Ohio, where his father worked for the Goodyear rubber company, Deniston had grown up obsessed with aviation. Goodyear had built two airships at Akron and as a boy he had followed their construction avidly, joining thousands of others to watch the test flights. Then, when he was still only eleven years old, a friend of his parents took him in a flight over Niagara Falls. It had been unbelievably thrilling. Another year, he managed to save up enough money for a trip on a Ford tri-motor, but while those flights were very rare treats, he still enjoyed spending as much time as he could at the Akron airfield, watching planes. When he grew up, he knew what he wanted to be: a pilot in the US Army Air Corps.

In 1939, Deniston entered Kent State University, and it was while there that he was given the chance to learn to fly. Having got through his civilian pilot training, he then applied for US Army Aviation Cadet Training. With his degree, and after a rigorous medical screening, he was accepted. In February 1941, he was told he was in – part of Class 42-C – and sent to Fort Hayes, Columbus, Ohio, to be sworn in and then posted to begin flying training. ‘Oh happy day!’ he noted.17 ‘I was on my way, hoping to make my dream come true.’ From Fort Hayes, he was put on a train to Los Angeles, California, and from there to Oxnard for Primary Flight Training. Within four days of his arrival, he was flying a Stearman biplane trainer and loving every moment. That he was training for war barely crossed his mind. He was flying. That was all that mattered.

A number of his fellow cadets were thrown out as the course progressed – a fate that had very nearly befallen another trainee pilot, Francis ‘Gabby’ Gabreski. The son of first-generation Polish immigrants, from Oil City, Pennsylvania, Gabreski had similarly developed a passion for flying at an early age. At Notre Dame University, where he had just managed to scrape himself in, he had begun private flying lessons, but discovered to his dismay that he lacked any kind of natural aptitude. After about six hours’ instruction, he ran out of money, but then the Army Air Corps recruiting team showed up on campus. By this time the war in Europe had begun and Gabreski, whose mother still spoke only Polish, was more keenly aware than most that Poland had been invaded and destroyed. He applied to join and was accepted.

He arrived at Parks Air College in East St Louis, Illinois, in July 1940, but two months later was still struggling to master flying. He was just too heavy-handed, and after a particularly dismal flying lesson in which he singularly failed to perform an adequate ‘lazy eight’ manoeuvre, his instructor told him flatly that if he continued training he would probably kill himself and take someone with him. He was putting Gabreski up for an elimination flight.

This would be his final chance to prove himself. The night before, Gabreski took himself off to a Catholic church and prayed hard. And as he did so, a feeling of confidence swept over him.

The next day he went up for his elimination flight and performed lazy eights, loops and slow rolls without too much problem. He even brought the plane down perfectly when his instructor unexpectedly cut the power on him. ‘I think you just need a little bit more time to catch up with the other students,’ his examiner told him.18 And a change of flying instructor. Gabreski had been given a second chance.

In March 1941 he graduated, and with around two hundred hours’ flying under his belt. This was more than either RAF or Luftwaffe pilots would expect to have before going operational. Gabreski knew he wasn’t the best pilot that ever lived, but he had got through and with his wings on his chest he had been posted to Hawaii and, even better as far as he was concerned, to a fighter unit, the 45th Fighter Squadron.

On Hawaii, Gabreski finally got to grips with flying as he notched up another thirty hours or more a month and was able to draw on the experience of his fellow pilots. ‘The training brings about experience,’ he wrote, ‘and once you get the experience, you have that final edge – professionalism.19 I pushed myself to the maximum every time I took an airplane off the ground. I wanted to make that airplane become a part of me.’

The rapidly growing US Army Air Forces had a huge advantage: a vast area of land in which to train in ideal weather conditions and without the threat of interruption by enemy attack. So, too, did the RAF, now that the Empire Training Scheme was fully under way in Canada and Rhodesia; having colonies and dominions around the world was proving very useful in this continuing war.

The same could not be said, however, for either the Luftwaffe or the Regia Aeronautica. The longer the war continued, the harder it was going to be for them to grow their air forces to the scale needed, just in terms of pilots and aircrew, let alone the manufacture of aircraft. It was another reason why German strategy had been to carry out short, sharp, decisive campaigns.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, the world’s only six-star general and Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe as well as President of Prussia, had been against BARBAROSSA. The Luftwaffe was the one arm of the Wehrmacht that had had no break to regroup and regain strength since the launch of the Western campaign on 10 May 1940 – when it had suffered catastrophic losses of some 353 aircraft, by some margin its worst single day since the war had begun. There had been no such catastrophe on the opening day of the campaign in the East, but the Luftwaffe was also conducting operations in North Africa and the Mediterranean, and against Britain from northern France and Norway. It was horribly stretched.

Göring had implored the Führer to reconsider. ‘The sacrifices made so far by the Luftwaffe in its attacks on England would be in vain,’ he told him.20 ‘The British aircraft industry would have time to recover; Germany would renounce certain sure victories (Suez, Gibraltar), and with them the possibility of reaching an agreement with England and, thereby, of guiding Russia’s armament activity into another channel.’ Hitler had replied, ‘You will be able to continue operations against England in six weeks.’

Göring’s arguments would have been more valid had the Blitz shown much sign of affecting British war industry, but he was right in principle. However, by the eve of BARBAROSSA he had acquiesced to the will of the Führer. ‘The rest of us,’ he told the Luftwaffe’s operational chief, Feldmarschall Erhard Milch, ‘we lesser mortals, can only march behind him with complete faith in his ability.21 Then we cannot go wrong.’

But they could. They could go very badly wrong.