I’m a visual filmmaker. I do films that are kinetic, and I tend to focus on character as it is created through editing and light, not stories. … I was always coming from pure cinema—I was using the grammar of film to create content. I think graphically, not linearly.

[Steven Spielberg] may have different aims from the aims of people we call artists, but he has integrity: it centers on his means. His expressive drive is to tell a story in shots that are live and hopping, and his grasp of graphic dynamics may be as strong as that of anyone working in movies now. The spatial relationships inside the frame here owe little to the stage, or even to painting; Spielberg succeeds in making the compositions so startlingly immediate that they give off an electric charge.

It is easy to think we understand what George Lucas is claiming when he says he is a “visual filmmaker,” not interested in “stories,” and furthermore, to quickly dismiss the rest of his statement about “pure cinema.” Both Lucas and Steven Spielberg have their contemporary champions. However, for their many doubters, it is just as tempting to view them primarily as CEOs of profit-making entertainment machines. Regardless of how one feels about them as filmmakers now, in the context of 1977 both directors’ public images and professional reputations were quite different from what they became in the ensuing decades. The stated investment in visual filmmaking and graphic dynamics places Lucas and Spielberg alongside the critically embraced auteurs of the New Hollywood generation like Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Terrence Malick, and Francis Ford Coppola. Auteurism, an approach specific to mid-century filmmaking initiated by French critics and filmmakers such as André Bazin and Alexandre Astruc, François Truffault and Jean-Luc Godard (but quickly spread around the world), and which valorized personal expression in resistance to the industrial machine, came to the U.S. mainstream comparatively late. Certainly, auteurism has been subject to many kinds of critiques over the last several decades, not least of which centers around the implausibility of one person controlling all aspects of the most collaborative art.3 I am not interested in reviving auteurism as an interpretive schema, but instead prefer to stress its historical importance to filmmakers of the film school generation, who were certainly suffused with the auteurist ethos from their art and film school teachers and American critics. Furthermore, while most critics perceive the special effects–driven blockbuster as the opposite of the auteurist-driven “personal” film, instead I see these films, especially Star Wars and Close Encounters, as extensions of this ethos, not rejections of it. As the Kael quote suggests (and other examples will show), most critics in 1977 did take both directors seriously as auteurist filmmakers, and as interesting and exciting ones seeking to establish a signature aesthetic style. This critical approbation did not last long, as many of the same critics, concerned with the effect blockbuster filmmaking was having on all production, would shortly begin to turn against Lucas and Spielberg. What were the factors that made Lucas’s and Spielberg’s 1977 films, Star Wars and Close Encounters, feel so original and innovative, both to critics and audiences? What social and cultural context helped spur their immense popularity? And which of those same factors later caused critics to view the kind of “visual filmmaking” they exemplified as the start of a dangerous trend that turned its back on the ideals of the 1970s out of which they emerged? Placing both films within their social and cultural historical context of 1977 illustrates how these films started to aesthetically transform popular filmmaking.

It is easy to think we understand what George Lucas is claiming when he says he is a “visual filmmaker,” not interested in “stories,” and furthermore, to quickly dismiss the rest of his statement about “pure cinema.” Both Lucas and Steven Spielberg have their contemporary champions. However, for their many doubters, it is just as tempting to view them primarily as CEOs of profit-making entertainment machines. Regardless of how one feels about them as filmmakers now, in the context of 1977 both directors’ public images and professional reputations were quite different from what they became in the ensuing decades. The stated investment in visual filmmaking and graphic dynamics places Lucas and Spielberg alongside the critically embraced auteurs of the New Hollywood generation like Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Terrence Malick, and Francis Ford Coppola. Auteurism, an approach specific to mid-century filmmaking initiated by French critics and filmmakers such as André Bazin and Alexandre Astruc, François Truffault and Jean-Luc Godard (but quickly spread around the world), and which valorized personal expression in resistance to the industrial machine, came to the U.S. mainstream comparatively late. Certainly, auteurism has been subject to many kinds of critiques over the last several decades, not least of which centers around the implausibility of one person controlling all aspects of the most collaborative art.3 I am not interested in reviving auteurism as an interpretive schema, but instead prefer to stress its historical importance to filmmakers of the film school generation, who were certainly suffused with the auteurist ethos from their art and film school teachers and American critics. Furthermore, while most critics perceive the special effects–driven blockbuster as the opposite of the auteurist-driven “personal” film, instead I see these films, especially Star Wars and Close Encounters, as extensions of this ethos, not rejections of it. As the Kael quote suggests (and other examples will show), most critics in 1977 did take both directors seriously as auteurist filmmakers, and as interesting and exciting ones seeking to establish a signature aesthetic style. This critical approbation did not last long, as many of the same critics, concerned with the effect blockbuster filmmaking was having on all production, would shortly begin to turn against Lucas and Spielberg. What were the factors that made Lucas’s and Spielberg’s 1977 films, Star Wars and Close Encounters, feel so original and innovative, both to critics and audiences? What social and cultural context helped spur their immense popularity? And which of those same factors later caused critics to view the kind of “visual filmmaking” they exemplified as the start of a dangerous trend that turned its back on the ideals of the 1970s out of which they emerged? Placing both films within their social and cultural historical context of 1977 illustrates how these films started to aesthetically transform popular filmmaking.It has become commonplace for critics and bloggers to claim that Star Wars changed everything in Hollywood, for better and for worse.4 While typically overblown, this rhetoric is not just empty exaggeration. These films represent a shift away from the unobtrusive Classical Hollywood cinema diegesis designed to be the optimal vehicle for narration transmission. Star Wars and Close Encounters transformed the parameters of a cinematic diegesis along a number of fronts. Rather than portraying a fictional setting that simply stages a fantasy narrative, these films drew attention to the intricately realized fantasy environment. Instead of the classical narrative economy of only presenting the viewer with the most salient narrative elements, the spectator is encouraged to imagine and explore the subsidiary storylines and locations. While this kind of fantasy engagement was available before to the particularly imaginative viewer, Star Wars and Close Encounters turned these explorations into a necessary part of the mediated experience. The films were only the jumping-off point of an expanded media experience.

Perhaps above all, narrative’s role shifted to become another area of potential attraction, instead of the primary organizing factor of the diegesis. Rather than a consequence of spectacle-driven filmmaking, filmmaker rhetoric suggests this shift was strategic and purposeful. This would be in contrast to what we consider the Classical Hollywood cinema, perceived by many New Hollywood filmmakers as an overly novelistic, story-driven style. When asked by an interviewer in 1977 if he was reconciled with classical narrative, Lucas replied:

No, I come from experimental cinema; it’s my specialty. … My friendship and my association with Coppola compelled me to write. His specialty is “literature,” traditional writing. He studied theater, text; he’s a lot more oriented towards “play writing” than I am: mise-en-scène scene, editing the structured film.5

Although Star Wars and Close Encounters maintain the expectations of mainstream narrative conventions, the kind of “experimental cinema” Lucas is talking about uses narrative as a structure for ordering audiovisual sensations and effects. Indeed, reviews and accounts suggest that spectators experienced these films as “a leap forward in realism,” and a visual absorption in the mise-en-scène was designed by idealistic filmmakers and special effects supervisors to stimulate what they conceived as a new, more “cinematic,” or visually based intelligence.6 This kind of visual communication, over traditional forms of “literature” or “text,” was more up-to-date and more in tune with what was perceived as the rapidly changing, technologically driven society.

Nevertheless, in large part because of the omnipresence Star Wars still enjoys in the culture, there is a general sense that both it and Close Encounters have been academically combed over for decades. However, though nearly all would agree on the films’ historical importance, there has been in fact very little close academic scrutiny paid to either film in great detail, outside of attention to their economic importance.7 Despite these films’ evident significance to the development of contemporary popular filmmaking, their enduring popularity (especially Star Wars) means that they have been effectively hiding in plain sight. A precise account of how these films attained such a pivotal place in cinema history deserves a detailed study.

There is little doubt, based on press coverage, fan magazines, and reviews, that Star Wars and Close Encounters succeeded with audiences in large part due to their spectacular, highly visible, and convincing special effects.8 How did it come to pass that special effects became the focus of these films’ production energy, and so central to their overall aesthetic program? Special effects have long been expensive, time-consuming, and risky. What did special effects provide that other methods could not? Why did these filmmakers believe that it was worth putting so much money and effort in special effects rather than to other areas of filmmaking? In addition to the influential aesthetic design of these two films, the production history behind their elaborate special effects demonstrates how feature filmmakers were able to convert the innovations made by Kubrick’s 2001 production into a viable working model for the rest of the industry.

Certainly, the success of Star Wars and Close Encounters initiated a shift in priority toward more special effects–driven filmmaking and had economic ramifications well beyond the effects business. As David Cook and others have pointed out, one of the major ways these films, along with earlier films such as The Godfather (1972) and Jaws (1975), changed much of the economics of Hollywood filmmaking was by convincing the conglomerates which had recently acquired movie studios that films could earn the same kind of serious money as other sectors of manufacturing.9 Focusing production energy toward more big-budget films and expensive stars to drive them has led to widespread economic changes in the industry—in production, exhibition, and ancillary markets as well as around deal-making, marketing and budgeting, and corporate “synergy.”10

Too often, an economic focus means discussions of Star Wars and Close Encounters become entangled and muddied by evaluative approaches. When academics and critics claim that Star Wars changed everything, it is often implied or stated outright that Star Wars changed Hollywood filmmaking, and specifically the aesthetics of filmmaking, for the worse. Star Wars very often stands as the prototype for the noisy, overproduced, expensive, juvenile Hollywood blockbuster that pushed out the more “mature” and “sophisticated” films by American auteurs such as Hal Ashby, Robert Altman, and Sidney Lumet, leaving the cinematic field to fourteen-year-olds and toy manufacturers.11 Regardless of one’s preferred style of filmmaking, it is more important to understand precisely how these films instigated a historical shift with implications and changes that mirror many aspects of the industry-wide shift to sound in the late 1920s and early 1930s—in aesthetics, technology, economics, and exhibition—and further, to understand that these films exhibit a recognizable and historically specific style that cannot be reduced to economic functionality. In other words, although making a lot of money is an important driving factor, filmmakers have other motivations and strategies in mind while designing the films.

The focus on economics and narrative in most examinations of special effects–driven films means that the look of these big-budget films, including today’s CGI-animated blockbuster, also tends to written off as “noisy,” “over-stuffed,” “frenetic,” and many other words associated with bad taste, and therefore not deserving of our attention. More neutrally, we may describe the characteristics of the special effects–driven blockbuster’s aesthetic as overflowing with kinetic action, taking place within a minutely detailed, intricately composed mise-en-scène, comprising an all-encompassing, expandable environment. Richard Maltby has influentially referred to a commercial aesthetic (with emphasis on the commercial), which might be stated more colloquially as “All the money is up there on the screen.” In a persuasive approach that explicitly “privileges economic relations rather than product styling,” Maltby’s commercial aesthetic understands the (loosely described) aesthetic as by-product of the commercial.12 In other words, blockbuster films look the way they do because they are designed with market forces in mind and because more money can mean more elaborate, expensive special effects, and therefore more production value. This aesthetic as Maltby describes it can be seen in many popular films of the last few decades—from Blade Runner to The Lord of the Rings films to The Matrix trilogy—in the way they foreground the marketable aspects of the movie’s style, and can be extrapolated into ancillary merchandise (“tie-ins”) bearing a recognizable logo associated with the style of the film.

Putting more consideration on the aesthetic side of the coin, Justin Wyatt characterizes Maltby’s commercial aesthetic in terms of high concept.13 He argues that blockbuster filmmaking, focusing primarily on 1980s filmmaking in the wake of the highly profitable 1970s blockbusters, reduces the film to a “pitch,” defined as a striking, easily reducible narrative, which offers a high degree of marketability.14 Importantly, the emphasis on salability does not end with the narrative. Using E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), Flashdance (1983), and Top Gun (1986) as exemplars, Wyatt also identifies a high-concept visual aesthetic, greatly indebted to advertising and practiced particularly by filmmakers who began as directors of TV commercials, notably Ridley Scott and Adrian Lyne. The high-concept aesthetic as Wyatt characterizes it permeates the film’s production, starting with a striking logo that sets the tone for all levels of the film’s visual style, driving the visual “look” of the production.15

Wyatt’s arguments certainly describe accurately the role of marketing in films of the 1980s. However, one begins to suspect that Wyatt is actually providing an answer to the implicit question, “Why are so many 1980s films so bad ?” It is precisely when he extends the notion of high concept in order to account for the aesthetic of the individual films that his argument becomes problematic and value-laden, effectively reducing “high-concept” films to advertisements for the more important ancillary products.16 While the altered relationship between the film and its ancillaries is an important factor, it need not be characterized as a devaluation of film art. Films have always been part of a web of entertainment economics. Therefore, rather than understanding the influence of advertising and ancillary commercialization as cheapening cinema as an art form, it is more useful to analyze and describe their aesthetics as parallel phenomena.

What clearly is suspect to Wyatt and others about the high-concept aesthetic is its emphasis on style. Although Wyatt’s study is undeniably provocative and well argued, it is weakened by a few common but unsustainable assumptions, the first being that foregrounded (“excessive” or “unmotivated”) style necessarily serves to weaken the all-important narrative. Second is the related worry that privileging style and aesthetics over narrative diminishes the film’s artistic significance.17 Unlike what we might call the “unity argument” in favor of Classical Hollywood’s unobtrusive (narratively motivated) style, or New Hollywood’s loosely narrated anti-style (as a rejection of Classical Hollywood storytelling), the flashy high-concept style is clearly to Wyatt and many others an indicator of the intellectual and political barrenness of individual films and the 1980s film industry as a whole. Although this demonizing of aestheticization and spectacle is beginning to dissipate as a leading critical stance in academe, it continues to hamper much of the meaningful discourse about the style of contemporary popular filmmaking.18 This approach devalues or ignores the fact that filmmakers were actively and consciously developing style-heavy aesthetics as part of an auteurist ethos.

Certainly, the widespread influence of Tom Gunning’s well-known “cinema of attractions” argument, while problematic to apply directly to post-early cinema, has served as an inspiration in recognizing how different kinds of films carry diverse pleasures. Furthermore, Gunning has provided a model for understanding the excitement and pleasure of filmmaking via its aesthetic effects.19 Moreover, it must be pointed out that a high-concept approach alone is not sufficient to carry a film. Regardless of how the film is marketed and conceived, and however it fits into a larger synergistic network, (variously talented) filmmakers and highly professional teams must still make a film that they believe is more than the sum of its marketing.

Focusing on aesthetics and the various pressures and influences over the many levels of production that make up a film’s (not always consistent) aesthetic program helps illuminate the contemporary critical enthusiasm for these films. A close look at the moment between the assumed heyday of the New Hollywood of the late 1960s and early 1970s and the commonly held “high-concept” nadir represented by the 1980s is instructive. It has been tempting to view the appearance of Star Wars and Close Encounters as the beginning of an end. However, it is clear from reviews and critical commentary that both films were received enthusiastically as a fresh and exciting development in auteur-driven popular filmmaking. On the whole, Star Wars and Close Encounters were better reviewed than 2001, even by the more prominent critics.20 Moreover, many critics such as Pauline Kael, Vincent Canby, and Stanley Kauffmann focused their enthusiasm on the films’ visual aesthetics.21

Moreover, it is not only that these mid-1970s style-driven films and their 1980s descendants look different though “cinema of attraction” eyes. The filmmakers behind Star Wars and Close Encounters were developing and modeling a then-fashionable notion of visual cinema. As Kubrick put it in relation to 2001,

movies present the opportunity to convey complex concepts and abstractions without the usual reliance on words. I think that 2001 [… succeeds] in short-circuiting the rigid surface cultural blocks that shackle our consciousness to narrowly limited areas of experience and is able to cut directly through to areas of emotional comprehension.22

Or, as he puts it more succinctly, people should be less word-oriented and more picture-oriented.23 Therefore, rather than dismissing films and filmmakers of this era for putting style before substance, it is more productive to recognize the substance of the style.

One might ask at this point, did Lucas, Spielberg, and Coppola, as well as the other young filmmakers of this era, consider themselves auteurs in Andrew Sarris’s meaning? On one hand, yes: they discussed in interviews their inspiration by the studio-era auteurs championed by Sarris and the Cahiers du Cinéma critics in the 1950s and 1960s, directors such as Howard Hawks, John Ford, and Orson Welles.24 Lucas, Coppola, and Spielberg explicitly considered themselves an extension of this auteurist tradition. This meant, first of all, they believed that the director should be in control of all elements of the film, and that the film itself would be a reflection of his or her own worldview. While at times this assumed control certainly broke down, Lucas and Spielberg believed themselves to be the ultimate arbitrators of all elements of the film. The filmmaking team and the press coverage assumed this as well. Finally, this perceived need to control, and the struggle over control (more on the part of Lucas than Spielberg), led largely to the shape of the special effects business as it has today become.

As filmmakers of this generation were taught over and over again in film school, and witnessed through the examples of their peers, one of the most marked aspects of an auteur was a recognizable style. In other words, filmmakers of the era had great personal stakes in developing and being recognized for an individual style, and for a while they were critically rewarded for it. However, they also considered themselves a new kind of auteur, more in keeping with social changes and technological innovations. Developing a personal style through developing special effects techniques was a strategic move away from Astruc’s “textual” caméra-stylo (or “camera-pen”) approach of previous models of authorship (where the filmmaker presents his or her view of the world in visual but essayistic form). Instead, the new-style auteur would seek to present his or her worldview “graphically,” rather than textually or literarily. Moreover, special effects offered directors the ability to control additional elements of visual design, to stamp the diegesis with their own imprimatur. Ironically, as then-critic (now film director) Olivier Assayas pointed out in a series of articles for Cahiers du Cinéma in 1980, the kind of highly technical, special effects–heavy films that Lucas and Spielberg were famous for undercut the “auteur genius” role they were cultivating.25 Because such films required an enormous amount of collaboration across a huge number of departments, how was one to keep them all in line with the auteur’s vision? And when the special effects on a film like Close Encounters were so remarkable and so publicly the product of a well-known effects artist like Douglas Trumbull, is Spielberg still the auteur? These questions, prominent in the public rhetoric, demonstrate the importance in defining the role of the auteur in a newly unstable production hierarchy.

The special effects–driven aesthetic developing in the late 1970s sought inspiration from many kinds of visual sources, both old and new. While casting an eye toward contemporary filmmaking and its precedents in the 1970s, Star Wars and Close Encounters, we must understand them as embedded within a matrix of filmmaking aesthetic traditions, from Hollywood’s “Golden Age” (as it was conceived at the time) to experimental practices, advertising, and animation, but also as attempts to inaugurate a new kind of popular Hollywood film. As noted in chapter 1 (with a nod to Gene Youngblood’s influential 1970 experimental film manifesto), I call this imagined popular/experimental hybrid the expanded blockbuster. For Lucas, Spielberg, and others, the expanded blockbuster would not just aim to make money and entertain the masses. They envisioned a popular style of filmmaking that would also be informed by the world auteurist movements of the 1960s and the U.S. avant-garde, especially the West Coast experimental scene championed by Youngblood. Instead of conveying ideas through didactic scripts and novelistic “themes,” the expanded blockbuster would take its cue from Kubrick’s 2001: it would be picture-oriented, or express its ideas and narration visually, on a more visceral and sensual level. And their most impassioned dream was that these films would remain in the creative hands of auteurist filmmakers, not corrupted by the corporate studio hierarchy. In other words, the ideal of 1970s filmmakers was to be like Jean-Luc Godard, John Ford, and Louis B. Mayer all rolled into one: someone who could strike a balance between “meaningful” and “personal” films, but also devise them to be popular and profitable enough to maintain independence and control the means of production. Although history has dubbed them the “Movie Brats,” their projects were conceived within post-hippie idealism, and with perhaps a conservative or naïve yearning for other kinds of worlds, for galaxies “far, far away” and not wracked by the problems of 1970s America.

However one interprets either film’s politics, it is important to remember that the Star Wars and Close Encounters of 1977 were a different beasts than the blockbuster progenitors most people consider them today. Its detractors often characterize Star Wars as mostly a cynical bid by Lucas to make a lot of money.26 What many nonenthusiasts tend to forget is that before its 1977 release, Star Wars was financed and produced more like a Roger Corman independent exploitation film than a big studio blockbuster in the way we think of the term today. It was explicitly budgeted, marketed, and expected to be a modest moneymaker for the science fiction and juvenile audience.27 Today, it is typically only widely known among Lucas’s fans that in the 1970s, based largely on THX-1138 and his student films that had made the festival rounds, George Lucas had the reputation as one of the artier and more esoteric of the young film school graduates. Contemporary reviews of Star Wars received it with the same kind of winking knowingness at past adventure genres they believed Lucas had meant it to be. They assumed Lucas was merely having ironic fun with an old-fashioned genre picture, but also making a kind of “statement” by choosing such a self-consciously retro project.28

Close Encounters, on the other hand, was conceived and produced as a bona fide studio project. As the new film from the director of Jaws, it had a much bigger budget and greater expectations. When asked to compare Close Encounters to Jaws, Spielberg responded:

Close Encounters has been more of a personal movie-making experience than Jaws. Jaws was a great physical challenge, but in a way it was a lot easier. A film like Jaws comes more naturally to my movie sensibilities than a film like Close Encounters, which is more experimental and daring in concept. Jaws is really a “one swallow” story, while Close Encounters contains a little more philosophical grey matter.29

Although Spielberg, then and now, resists intellectualizing his films, it is striking that after the enormous popcorn film success of Jaws, he claimed he was also looking to inject philosophical ideas and meaning, or as he put it, “grey matter,” into popular filmmaking, in terms expected from ambitious filmmakers of the era.

Comparing these two films, we can see how the many possible approaches to special effects production in the 1960s and 1970s were brought together on two of the biggest hits of the era, two films that (along with Jaws) define blockbuster film. Specifically, they established the model for the special effects–driven blockbuster still with us today. The two films had very similar technological programs and special effects problems they felt they needed to solve. However, they pursued surprisingly divergent aesthetic programs. Again, Kubrick approached 2001 as an expensive one-time-only experiment, without an eye toward future special effects productions. The way the Star Wars and Close Encounters productions were able to employ much of the same technology for very different aesthetic results in part shows the flexibility of the new imaging systems the productions developed that helped spawn a whole new industry for feature film special effects production.

In order to achieve the aesthetic goals they set for themselves, both film productions had enormous technical tasks at hand. And certainly, the technology used determined to some degree the resulting aesthetic. Also, in both cases, Star Wars and Close Encounters set out to flaunt their technology, precisely by displaying its aesthetic potential. Star Wars begins with the famous Imperial cruiser flyover. It is a 30-second, all-effects shot: planets, model ships, a star field, and so on are composed and composited to make a completely imaginary mise-en-scène. Everyone involved was fully aware that the film would succeed or not by how convincing they made those thirty seconds. Conversely, Close Encounters spends its first half hour or so establishing Roy Neary’s (Richard Dreyfus) mundane, average existence as a telephone repairman in suburban middle America with a nagging wife and bratty kids. The first full UFO sighting is delayed for about thirty minutes, in part to build suspense and anticipation, and in part to heighten the contrast between the dazzling and awe-inspiring UFOs and the ordinary setting.

By shifting a good deal of energy and money toward postproduction, the special effects in Star Wars and Close Encounters exemplify the newly restructured hierarchy of conventional support skills. Traditionally, the studio effects department, like the costume or construction departments, was only one of the many artisanal divisions taking orders from production heads. Each department was important to the film in its way, but not typically involved with creative input in the planning stages. In the 1970s, as productions began to rely so heavily on the success of their effects, the director and/or producer (often the same person) had to rein in the effects sector of production. As the division between the main unit and the effects unit began to blur, relations between the director and the effects supervisors became more important. They also could, and did, as was the case with Star Wars, become tense.

How could producers control the huge number of elements needed to create these multilayered composites, and how were they to corral the approaches of the huge number of diversely trained artist-technicians needed to mold such a huge project into their personal visions? Star Wars’ and Close Encounters’ sheer density of effects, both in an individual shot (or frame) and in the film overall necessitated the careful planning of principal photography for the effects to be added later. In other words, the auteur theory to which so many young filmmakers like Lucas and Spielberg subscribed ran into the problem of sheer unwieldy size, undreamt of by their studio-era heroes or scrappy independents. Put simply, how do you get your personal vision on the screen when you have so many people to contend with?

1970s Filmmmaking Aesthetics: Thinking Graphically

I’m interested in pure experience rather than linear plot. … I saw [Close Encounters’] major end-sequence as an experience that almost transcends plot.

Trumbull’s quote suggests a question: if the sort of optical animation being developed through special effects production is meant to harness the kinetic and sensual qualities “beyond plot” of expanded cinema, how does that translate to a narrative feature film, from which spectators expect character-based narrative coherence? This also leads to the question, what was it about Star Wars and Close Encounters that looked so fresh to so many critics and filmgoers? The contemporary trend for “graphic dyanmics” and “thinking graphically” were particularly urgent topics in the 1970s for filmmakers. These filmmakers looked to the many experimental filmmakers such as John Whitney Sr., Jordan Belson, and Pat O’Neill, who were also concerned with the graphic potential of abstract (or abstracted) imagery to produce various kinds of effects and/or experiences in the viewer. Although differing from filmmaker to filmmaker, and from film to film, a few consistent preoccupations included a sense of forward momentum, rapid variation, hypnotic absorption, soothing pattern recognition, pulsating energies, and, sometimes, jarring discontinuities in the viewer. It was these shared concerns, along with more practical matters of the economics of filmmaking, that brought these two groups together in the late 1970s.

Although experimental animators were among the first to take up and develop the notion of graphic dynamics, the concept was not only conceived of in terms of deliberately paced graphics and carefully framed compositions. Editing played an important role as well. Many film schools taught well-known examples of avant-garde editing techniques, such as Soviet montage, in particular Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), which were also studied obsessively by film students and filmmakers on the art film circuit.31 For example, as many of Lucas’s 1970s interviewers attest, Lucas kept a poster of Eisenstein in his editing room, an emblem of his USC film school education.32 However, it is important to note that what is at stake is not a replication or modification of Eisenstein’s or Vertov’s specific theories and techniques. On occasions in 1960s and 1970s filmmaking discourse where Eisenstein’s name is mentioned, he more often appears as a byword for creative or “artistic” editing, someone who diverged from traditional Hollywood continuity editing.33 Rather than Eisenstein’s better known “intellectual montage” (which created mental associations through conflict), the kind of editing that caught on in the film schools was more often his ideas emphasizing the musical analogy of visual rhythm.

Filtered through Vorkapich, this became graphic dynamism. Vorkapich helped pioneer the “montage sequence” as it is popularly understood today: the compression of time or space represented by a series of overlapping, graphically arranged images, usually set to music (the rousing training montage in Rocky [Avildsen, 1976] or the opening of Woody Allen’s Manhattan [1979], set to George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” can serve as familiar examples). Like Kubrick, many 1970s filmmakers and theorists were looking for what was considered the visual power of cinema to carry ideas and to create sensations that were specifically cinematically induced, such as Kubrick’s “disembodied” virtual camera movement through space in 2001, or startling visual juxtapositions such as the film’s famous bone/spaceship match cut. Gene Youngblood also bolstered awareness of Vorkapich’s ideas in Expanded Cinema.34

Montage sequences generally, and Vorkapich’s in particular, help to illustrate one crucial way this 1970s sense of “thinking graphically” hinged on the design and execution of the special effects. Montage techniques as they had been applied in the past allowed a limited number of elements that could be composed at any given time (due to the difficulty of compositing many elements at once). In montage sequences, the film frame is usually split up into discreet “windows,” either strictly contained or expressionistically superimposed. Through habit, the viewer knows he or she is not meant to take these images as an illusionistic, integrated photoreal composite. As in Vertov’s split screens, Eisenstein’s superimpositions, Vorkapich’s transitional techniques, or Linwood Dunn’s elaborate wipes made with traveling mattes, we can recognize an in-frame montage technique that is often meant to carry visual energy and dynamism over to the next sequence, with varying degrees of narrative motivation. Graphic dynamics in the 1970s modifies this tendency by removing the connotation of time/space compression and also by blurring or breaking down the montage sequence’s imposed boundaries. Instead, the illusionistic composite mise-en-scène retains some of the associated energy of a montage sequence—in its rapidly changing pace and dynamic and thought-provoking juxtapositions of images which, naturalistically, shouldn’t be in the same space. Most importantly, 1970s dynamic graphics ramp up the amount of elements to be composed and often make them appear to be part of the same coherent diegetic space. In other words, 1970s graphic dynamics combine the impact of graphic design with the integrated spaces of traditional special effects composite techniques. Both Star Wars’ and Close Encounters’ productions wanted to design the effects to have a more graphic look and dynamic impact than just the traditional ship flying horizontally across the frame, filmed by a static, locked-off camera.

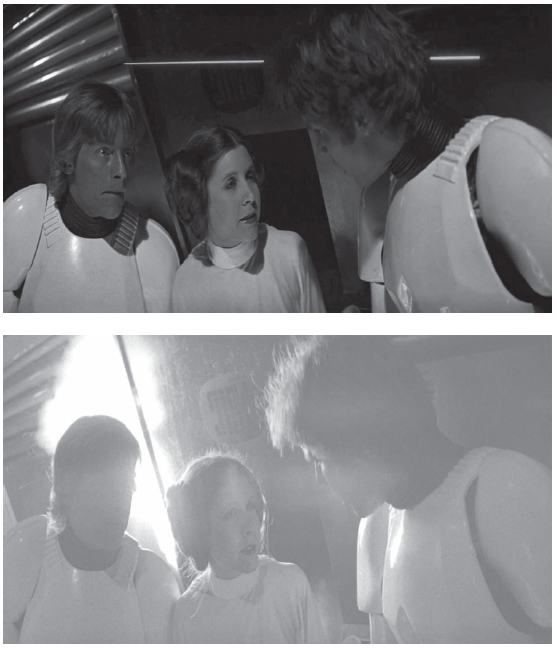

Vorkapich believed that “since the nature of the cinema is movement, filmmakers should best exploit cinematic technique for maximum dynamism and kinesis.” According to Vorkapich, graphic dynamism offered a cinema-specific, “vivid kinesthetic experience” that reached the artistic level and complexity of poetry or symphonic music.35 When Lucas promotes “thinking graphically” over thinking linearly, he is suggesting that composing the frame so that the juxtaposition of composed elements, how they move, and the effect of that movement, is as important as the the way the order of the story is presented. A simple example might be the graphic wipes in Star Wars, or the way the aerial laser fights are edited to string together the animated streaking laser beams, followed by a brightly colored filtered explosion, with sparks, and a color strobe of the screen in quick succession, repeated many times over the course of the fight (figs. 3.1 and 3.2). A more elaborate example might be the attack of the Imperial Walkers on the ice planet Hoth, in The Empire Strikes Back, with the distinctively elephantine movements of the Walkers contrasted with the zippy fighter planes and the faux point-of-view shots that capture them (fig. 3.3).

Needless to say, Star Wars and Close Encounters also feature a familiar classical sense of narrative forward momentum. It is no doubt an important aspect of their popularity that the films manage to supply conventional narrative drive and a fresh staging of visual storytelling at the same time. In fact, one of the ways these films were distinguishable from (and, in the opinion of both directors and many contemporary critics, improved upon) the legacy of 2001: A Space Odyssey was by picking up the pace of the storytelling and situating the graphic visuals within a compelling narrative populated with charismatic actors and vivid characterizations. That said, both films, though superficially conforming to classical narrative standards, nevertheless upset the priorities of the classical narrative drive in important ways. They maintain coherent characters and plots, but at the same time shift attention away from them and toward the more loosely organized excitement generated in the action sequences. This is the very excitement that Luke Skywalker craves at his aunt and uncle’s ranch, and that Roy Neary finds lacking in his role as suburban father. Further, these films provide influential models for narrative patterning for later special effects–driven blockbusters. Despite many critics’ complaints to the contrary, contemporary blockbusters certainly maintain screenplay patterns and structures as traditional as any classical screenplay, as Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell have argued.36 However, although one could analyze films like Titanic (1997) or Transformers (2007) and find they have a perfectly classical narrative structure, it is safe to say that the attraction of those films, and the reason people go to the cinema to see them, must be described as that of sensation, kineticism, and spectacle.

Even more far-reaching than narrative shifts, 1970s special effects work altered the sense of a cinematic diegesis toward one concerned with establishing a fully realized fantasy environment to imagine and explore, rather than just a fictional setting for the story. In terms of the special effects, the diegesis shifted from being largely a matter of compositing the foreground and background (as it had been in the classical era where the latter is clearly subordinate to the former) in the most unobtrusive way possible, to the freeing up of the picture plane to be as plastic and mutable as animation.37 The ability to completely design and mobilize the mise-en-scène, as in the opening shot of Star Wars, to manipulate its photographic elements and present a more densely packed and composed composite, is optical animation in a nutshell. The technology developed for Star Wars provides compositional control of the image within the frame rather than in the editing between frames. A major impact of Star Wars was not only that many elements were composited together photorealistically but also that their sounds and movements were equally designed and choreographed for graphic effect. In the case of Trumbull’s effects for Close Encounters, the “pure experience” over plot (as Trumbull puts it in the opening quote to this section), is meant as a mobilization of a different order of intelligence, one that understands visually and, more precisely, cinematically rather than novelistically.

The sheer number of elements used to produce this kind of graphic dynamic impact was enormous. In the original 1977 Star Wars, it is still remarkable to notice not just the densely packed frame38 but also the often irregular, heterogeneous visual material.39 Some effects shots used live-action, miniatures, projection, animation, rotoscoping, and still photography in the same sequence—for example, when Luke swoops in and out of the canyons in the destruction of the Death Star. How did all this heterogeneity manage to cohere into a fictional diegesis? On a visual level, I have argued they did not, whether purposefully or not. As already suggested, the Star Wars team was required to blend a great deal of diverse special effects practices and filmmaking and design styles, which, following the musical analogy, tended to result in visual cacophony. However, for the late 1970s, psychedelia-accustomed viewer, instead of experiencing the heterogeneity of special effects techniques and approaches as confusing and incoherent, viewers found them arranged and composed in such a way as to be constantly changing, textured, and varied.40 We can also relate the overstuffed frame to live-action examples of New Hollywood filmmakers like Robert Altman (especially Nashville [1975]), who piled characters, soundtracks, and narrative incident into the same frame.41

Often, the filmmakers framed their rhetoric about density in terms of increased visual sophistication demanded by viewers in the information age. As Douglas Trumbull said, “I think that people’s ability to assimilate information is tremendously high, and the reason most movies are unsuccessful is because they don’t have any impact.” What Trumbull means is that most movies are statically staged and visually staid.42 For both Trumbull and Lucas, “impact” meant a kind of visual density combined with kinetic movement. For both films, in fact, the intense concentration of visual information was considered highly (and, often, pleasantly) disorienting at the time of their release.43 The visual dynamics lit up the conventional narratives and infused them with the kind of “impact” Trumbull was looking for.

However, the expanded blockbuster is not just a barrage of colored lights or succession of kinesis-inducing shapes and patterns. Filmmakers believed it had to work conventionally as well, and that meant using special effects more traditionally to build a coherent environment for the narrative. Vitally, what made these films so striking as mainstream films and so influential to later films is their complex combination of photography, animation, and graphic design—not to fool viewers to mistaking that what they see is “real” but, more accurately, presenting a new style of photorealism that struck viewers as both fantastic and strikingly realistic.44 Star Wars’ aim was to make a fantasy world seem both plausible and fully realized. Conversely, Close Encounters brings fantastic elements into a mundane, familiar context. As discussed in the last chapter, the very active and diverse independent service companies—specifically, the title, optical, and effects houses of the 1960s and 1970s—provided a training ground in the practical, hands-on optical techniques for effects teams that would contribute so crucially to Star Wars and Close Encounters. The various skills and qualifications of such “on the job” training contributed directly not only to the look of Star Wars and Close Encounters but also affected how we have arrived today at the nearly fully animated Hollywood special effects–driven blockbuster.

Credible and Fantastic at the Same Time: Special Effects Aesthetics Circa 1975

I remember [going to George Lucas’s house], and I saw he had some Flash Gordon Comic strips, drawn by Alex Raymond, on his desk, and a picture of Eisenstein on his wall, and the combination of those two were really the basis for George’s aesthetic in Star Wars.

We had to be down on earth with totally believable illusions. Putting a UFO on screen is like photographing God. So the general look we went for was one of motion, velocity, luminosity and brilliance.

—DOUGLAS TRUMBULL (1977)46

Although Jay Cocks’s statement should be taken with caution, a “combination of Flash Gordon and Sergei Eisenstein” is an apt summation of the wide-ranging interests and influences of the so-called New Hollywood directors, of whom Lucas and Spielberg were certainly a part.47 As Thomas Elsaesser put it, U.S. filmmaking in the 1970s is marked by “the unlikely blend … of avant-garde and exploitation.”48 This was partly because many of the filmmakers in question (e.g., Martin Scorsese, Peter Bogdanovich, Monte Hellman, James Cameron) famously made their first films as professionals for Roger Corman’s “quick and dirty” production companies, AIP (American International Pictures) or New World Pictures. As is well known, at Corman’s, as long as the picture came in on time and on budget and contained enough exploitation elements (some violence, mild nudity) to play at a drive-in, the filmmakers were free to do whatever they wanted.

Lucas and Spielberg did not work for Corman (although Lucas’s Star Wars producing partner Gary Kurtz did), but they were among the same peer group of directors who directed their first features for him. Although journalists have well documented Lucas’s and Spielberg’s careers over the years, it is worth briefly rehearsing their stories for the uninitiated. Of course, the two directors have always been closely associated with the turn to blockbuster filmmaking, as well as with each other. Their business association extends back to the time of Star Wars and Close Encounters, when they gave each other profit-sharing “points” for one another’s films, and has continued for decades.49 However, by the mid-1970s the two men had quite different reputations and were at different points in their careers. Spielberg’s previous film, Jaws (1975), had opened huge (becoming the then-highest-grossing movie of all time), and for Close Encounters he had the full resources of the studio system behind him. Lucas had had a surprise hit with American Graffiti (1973), but bad blood with the studios persisted from editing battles over that film and his previous film, THX-1138. Lucas was considered doubly problematic by the studios, for being both esoteric and willful.

Lucas attended USC film school, where he was known for semiabstract and surprisingly polished prize-winning student films. His professional career started with Coppola’s American Zoetrope, an independent production company that had distribution deals with the studios, specifically Warner Bros. Lucas’s problems with the studios began with the commercial failure of the feature version of his bleak and edgy student film THX-1138, which caused the studio to withdraw Zoetrope’s funding. He followed THX with the huge surprise success of American Graffiti, a mix of pre-hippie nostalgia (“Where were you in ’62?”) and neon-lit, minimally narrative musical sequences.50 Both films, however, had been subject to what Lucas considered arbitrary studio interference and cuts. This experience of loss of control over his films appears to have bruised his auteurist ego, and it seems he has spent the rest of his career, and used his considerable wealth, consolidating his power over his productions and companies. In 1977, in attempting to launch his own production company with Star Wars, Lucas knew he first had to amass a great deal of money if he wanted the artistic freedom to make his “visual films.” Star Wars was conceived as a film that would test his idea of a popular film mixed with elements of “pure cinema.”51

Spielberg’s self-taught career trajectory is equally well-told.52 He started making narrative short films as a boy in his parents’ backyard (with his little friends as World War II soldiers), and then showed them in the basement to neighbors. He studied filmmaking at Long Beach State (not the more prestigious Southern California film schools USC or UCLA), and at twenty-one finagled a job on the Universal lot. His first professional jobs were shooting TV episodes for Universal series such as Night Gallery (starring Joan Crawford), Marcus Welby, MD (with Robert Young), and Columbo (with Peter Falk). After receiving positive critical recognition for Duel (1971), a suspenseful TV movie that played in some European film festivals, and making a well-regarded splashy feature debut with The Sugarland Express (1974), Spielberg directed his monster hit Jaws. Though lauded for his obvious filmmaking talent and his commercial instincts, Spielberg was at that point not taken as seriously as an auteur as Lucas53

After Star Wars, Lucas learned a lesson from the financial failure of American Zoetrope, Coppola’s attempt to create a more director-friendly studio outside of Hollywood. Instead of creating a European-style filmmaking collective, Lucas took his Star Wars profits and reproduced the top-down, producer-based control of the studio system in miniature with Lucasfilm, but far away from Hollywood in Northern California’s Marin County. Lucasfilm would, first of all, produce films with recognizable popular appeal.54 In order to elevate his status within his peer group, Spielberg had to figure out how to add “depth” and “grey matter” to the popcorn films that came so easily to him. Always known as more collaborative and open to others’ opinions than Lucas, Spielberg publicly resisted the auteur label. Starting production on their 1977 films with the self-imposed goals of making both a popular and a significant film, they looked to popular and avant-garde precedents to realize that aim.

Again, the significance of these films would ride in large part on their fresh approach to visual aesthetics. Like 2001 before them, what made Star Wars and Close Encounters so remarkable at the time was that not only were the effects convincing but they also had a specific, designed look that carried through to all levels of production. Unlike the imperceptible studio-era ideal, what was surprising and impressive about Star Wars and Close Encounters was that the filmmakers designed their effects to be seen and admired. The effects were to be experienced as both entirely in keeping with the diegesis and as a technological attraction in themselves.

The emphasis on verisimilitude is prevalent in their discussions of special effects; the filmmakers’ goal of greater realism seems indisputable. What gets lost in focusing on the desire for credibility is the second half of the formula: it must be credible and fantastic—a believable illusion. What should be stressed is less the fantastic in favor of the credible (or vice versa) than their historically specific relationship, and the way the two films negotiated this relationship in different ways.

Ironically, despite the wide-ranging expertise of the personnel available within the independent effects industry, neither Lucas nor Spielberg initially looked to the broader service and supply industry to staff their productions. Rather, they canvassed the only other people who had experience in such large-scale effects projects—the remaining old-hand studio technicians.55 Unhappily, when hiring for Star Wars and Close Encounters began, many effects-heavy projects were already under way by the studios (including the disaster films, the de Laurentiis King Kong remake, etc.), which tied up many of the (rehired) traditional studio technicians and mainline independent houses, such as Dunn’s Film Effects Hollywood.56 Lucas and Spielberg were forced to look farther afield to less established outside sources, for their supervisors and crews.

In both cases, they first considered Douglas Trumbull. Trumbull and Lucas apparently did not see eye to eye, and Trumbull passed on Star Wars. As Lucas put it (well after the fact):

If you hire Trumbull to do your special effects, he does your special effects. I was very nervous about that. I wanted to be able to say, “It must look like this, not that.” I don’t want to be handed an effect at the end of five months and be told, “Here’s your special effect, sir.” I want to be able to have more say about what’s going on. It’s really become binary—either you do it yourself, or you don’t get a say.57

Lucas’s statement offers more evidence of the kind of producer-centered control he was building in independent form at Lucasfilm. However, in a study of the aesthetics of special effects, it also brings up a thorny issue: who’s aesthetic is it? Lucas acknowledges the reality that the visual effects supervisor can have a disproportionate influence over the final look of the film, so that it matters who is in charge. As Scott Bukatman has convincingly argued, as special effects became more visible and spectacular in the 1970s, the industry saw the rise of what he calls the “special effects auteur.” However, he seems to argue that Trumbull is the only one who consistently fulfills such a role.58 As we shall see, there are historical reasons that the special effects auteur failed to endure beyond the 1980s. Certainly, Trumbull was instrumental in developing a more prominent role for the special effects supervisor and putting his personal stamp on a recognizable aesthetic. However, it is important to place Trumbull in a broader historical context, instead of overemphasizing his uniqueness.

As a heuristic, it is tempting to starkly contrast the different cases of Star Wars and Close Encounters. Nevertheless, one should not fall into the trap of setting up too sharp a divide in the Lucas/ILM versus Trumbull/Future General binary, especially one that favors one side over the other. In 1975 they had as many points in common as they did points of divergence. The two men rose from similar training backgrounds, shared many of the same technological goals, and hired many of the same personnel in their organizations. Both wanted to work independently of the studios while at the same time still needing them for wide distribution. Both were looking to revitalize the very idea of popular entertainment and reshape what audiences wanted. They sought to update exhibition technologies and practices. And they both believed that making special effects more credible and more fantastic at the same time was the key to revitalizing the popular blockbuster formula. The challenge will be to carefully map out the terrain they both occupied, and where they diverged.

Many special effects artists got into the business initially because of 2001 and the prominent and creative role the effects had in the overall film. After Star Wars demonstrated the increased importance of postproduction, all ambitious effects supervisors began to understand their position as keepers of a highly specialized and desirable skill set. Instead of being considered mere hired hands, Dykstra, Trumbull, Rob Blalack, and other prominent effects supervisors of the era began agitating in the press for more recognition of their considerable efforts, and more influence over productions. Dykstra even foresaw a day when special effects artists might receive the same recognition as actors: “Special effects people are not technicians, they are artists, and deserving of the same kind of deference that is given to the people in ‘star’ roles.”59 Not surprisingly, directors and producers, and even production designers (i.e., those in the traditional positions of power), did what they could to undermine that impulse, and many power struggles played out over special effects for the ensuing decades. The specific case between Lucas and his own Star Wars effects supervisor, John Dykstra, along with the problems faced by the burgeoning independent feature effects industry, will be discussed in more detail later.

In large part, the economic dominance of Star Wars and its two sequels in the early 1980s generated a style and technique of special effects that would become characterized as the Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) house style. As already discussed, the ILM style has become the dominant model for how all special effects are described and judged. More specifically, I previously characterized the ideal ILM aesthetic as perfectly executed, seamless photorealism, with an emphasis on character-based anthropomorphism, and kinetic movement having a flashy graphic quality within a busy, zippy frame. Additionally, these visible and dazzling effects would continually seek to refresh the “wow” factor of cinematic spectacle, rather than pass by unnoticed as perfect illusion. However, this characterization does not exhaust the many facets of ILM’s effects production. More importantly, we should remember that, however natural ILM’s effects might seem to us today, the ILM aesthetic is a style, and a historically determined one.

It is easy to think we understand what George Lucas is claiming when he says he is a “visual filmmaker,” not interested in “stories,” and furthermore, to quickly dismiss the rest of his statement about “pure cinema.” Both Lucas and Steven Spielberg have their contemporary champions. However, for their many doubters, it is just as tempting to view them primarily as CEOs of profit-making entertainment machines. Regardless of how one feels about them as filmmakers now, in the context of 1977 both directors’ public images and professional reputations were quite different from what they became in the ensuing decades. The stated investment in visual filmmaking and graphic dynamics places Lucas and Spielberg alongside the critically embraced auteurs of the New Hollywood generation like Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Terrence Malick, and Francis Ford Coppola. Auteurism, an approach specific to mid-century filmmaking initiated by French critics and filmmakers such as André Bazin and Alexandre Astruc, François Truffault and Jean-Luc Godard (but quickly spread around the world), and which valorized personal expression in resistance to the industrial machine, came to the U.S. mainstream comparatively late. Certainly, auteurism has been subject to many kinds of critiques over the last several decades, not least of which centers around the implausibility of one person controlling all aspects of the most collaborative art.3 I am not interested in reviving auteurism as an interpretive schema, but instead prefer to stress its historical importance to filmmakers of the film school generation, who were certainly suffused with the auteurist ethos from their art and film school teachers and American critics. Furthermore, while most critics perceive the special effects–driven blockbuster as the opposite of the auteurist-driven “personal” film, instead I see these films, especially Star Wars and Close Encounters, as extensions of this ethos, not rejections of it. As the Kael quote suggests (and other examples will show), most critics in 1977 did take both directors seriously as auteurist filmmakers, and as interesting and exciting ones seeking to establish a signature aesthetic style. This critical approbation did not last long, as many of the same critics, concerned with the effect blockbuster filmmaking was having on all production, would shortly begin to turn against Lucas and Spielberg. What were the factors that made Lucas’s and Spielberg’s 1977 films, Star Wars and Close Encounters, feel so original and innovative, both to critics and audiences? What social and cultural context helped spur their immense popularity? And which of those same factors later caused critics to view the kind of “visual filmmaking” they exemplified as the start of a dangerous trend that turned its back on the ideals of the 1970s out of which they emerged? Placing both films within their social and cultural historical context of 1977 illustrates how these films started to aesthetically transform popular filmmaking.

It is easy to think we understand what George Lucas is claiming when he says he is a “visual filmmaker,” not interested in “stories,” and furthermore, to quickly dismiss the rest of his statement about “pure cinema.” Both Lucas and Steven Spielberg have their contemporary champions. However, for their many doubters, it is just as tempting to view them primarily as CEOs of profit-making entertainment machines. Regardless of how one feels about them as filmmakers now, in the context of 1977 both directors’ public images and professional reputations were quite different from what they became in the ensuing decades. The stated investment in visual filmmaking and graphic dynamics places Lucas and Spielberg alongside the critically embraced auteurs of the New Hollywood generation like Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, Terrence Malick, and Francis Ford Coppola. Auteurism, an approach specific to mid-century filmmaking initiated by French critics and filmmakers such as André Bazin and Alexandre Astruc, François Truffault and Jean-Luc Godard (but quickly spread around the world), and which valorized personal expression in resistance to the industrial machine, came to the U.S. mainstream comparatively late. Certainly, auteurism has been subject to many kinds of critiques over the last several decades, not least of which centers around the implausibility of one person controlling all aspects of the most collaborative art.3 I am not interested in reviving auteurism as an interpretive schema, but instead prefer to stress its historical importance to filmmakers of the film school generation, who were certainly suffused with the auteurist ethos from their art and film school teachers and American critics. Furthermore, while most critics perceive the special effects–driven blockbuster as the opposite of the auteurist-driven “personal” film, instead I see these films, especially Star Wars and Close Encounters, as extensions of this ethos, not rejections of it. As the Kael quote suggests (and other examples will show), most critics in 1977 did take both directors seriously as auteurist filmmakers, and as interesting and exciting ones seeking to establish a signature aesthetic style. This critical approbation did not last long, as many of the same critics, concerned with the effect blockbuster filmmaking was having on all production, would shortly begin to turn against Lucas and Spielberg. What were the factors that made Lucas’s and Spielberg’s 1977 films, Star Wars and Close Encounters, feel so original and innovative, both to critics and audiences? What social and cultural context helped spur their immense popularity? And which of those same factors later caused critics to view the kind of “visual filmmaking” they exemplified as the start of a dangerous trend that turned its back on the ideals of the 1970s out of which they emerged? Placing both films within their social and cultural historical context of 1977 illustrates how these films started to aesthetically transform popular filmmaking.