Chapter 11

Responding to Criticism

You’re painting your bedroom, feeling good about getting the job done. The room looks like new. Somebody comes in and says, “It looks pretty good. Is that the color it will be when it dries? Did you really want it that bright? Uh oh, look at all the splatters on the floor. You’ll never get that enamel off if you let it dry.”

Your mood is ruined. The room that looked so fresh and sparkling now looks garish and sloppy. Your self-esteem withers under the criticism.

The negative opinions of other people can be deadly to self-esteem. They say or imply that you are not worthy in some way, and you can feel your own opinion of yourself plummet. Criticism is such a powerful deflator of weak self-esteem because it arouses your own internal pathological critic and supplies him with ammunition. The critic inside senses an ally in the critic outside, and they join forces to gang up on you.

There are many types of criticism. Some is even constructive, as it is when the critic is motivated by a desire to help and couches the criticism in terms of good suggestions for change. Other times, criticism is just nagging, a pointless, habitual recitation of your failings. Often your critic is engaging in one-upmanship, trying to appear smarter, better, or righter than you. Or perhaps your critic is being manipulative, criticizing what you’re doing in an attempt to get you to do something else.

Whatever the critic’s motive, all criticism shares one characteristic: it is unwelcome. You don’t want to hear it, and you need ways to cut it short and prevent it from eroding your self-esteem.

Actually, criticism has nothing to do with true self-esteem. True self-esteem is innate, undeniable, and independent of anyone’s opinion. It can be neither diminished by criticism nor increased by praise. You just have it. The trick to handling criticism is not to let it make you forget your self-esteem.

Most of this chapter will deal with the arbitrary, distorted nature of criticism. Once you understand and have practiced the skills of discounting criticism, you will go on to effective ways to respond to critics.

The Myth of Reality

You rely on your senses. Water is wet. Fire is hot. Air is good to breathe. The earth feels solid. You have found so often that things are exactly what they seem to be that you have come to trust your senses. You believe what they tell you about the world.

So far so good, as long as you stick to your sense impressions of simple inanimate objects. But when people enter the picture, it gets more complicated. What you expect to see and what you have seen before start to affect what you thought you saw. For example, you see a tall blond man grab a woman’s purse and jump into a tan two-door sedan and roar away down the street. The police come and take your statement, and you tell them exactly what you saw. But the woman who lost her purse insists it was a dark-haired, short guy. Another bystander says the car was gray, not tan. Yet another person is sure it was a 1982 station wagon, not a sedan. Three people claim to have noted the license, and by cross-checking their stories the police think it was LGH399 or LGH393, or maybe LCH399.

The point is that in the heat of the moment, you can’t trust your senses. Nobody can. We all select, alter, and distort what we see.

A TV Screen in Every Head

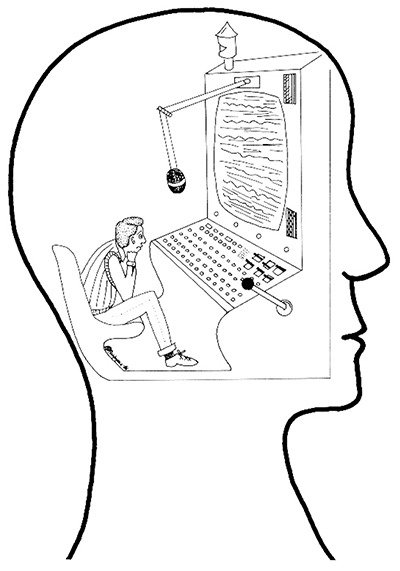

The example above shows that you rarely perceive reality with 100 percent accuracy and objectivity. Most often you filter and edit, as if your eyes and ears were a TV camera and you were seeing reality on a screen in your head. Sometimes the screen is not in focus. Sometimes it zooms in on certain details and omits others. Sometimes it magnifies or minimizes. Sometimes the colors are off or the picture shifts to black and white. Sometimes when you are remembering the past, the screen shows you old film clips, and you see no “live” reality at all.

Your screen is not usually a bad thing. Essentially it reflects the way your senses and your mind are wired together. Without the ability to manipulate images on your mental screen, you could never cope with the flood of information assailing you from the outside world. You could never organize and use past experience. You could never learn or remember. As suggested by figure 1, your screen is a fabulous machine, with lots of buttons and levers to play with.

Here are some important rules about screens:

- Everybody has one. It’s how human beings are wired.

- You can only see your screen, not reality directly. Scientists train rigorously to become as perfectly objective as they can. The scientific method is a very precise way to make sure that what researchers are looking at is really there and is really what they think it is. Nevertheless, the history of science is rife with examples of sincere scientists who have been betrayed by their hopes, fears, and ambitions into propounding false theories. They mistook their screens for reality.

- You can’t fully know what is on someone else’s screen. You would have to become that person or possess telepathic powers.

- You can’t fully communicate what’s on your screen. Some of what affects your screen is unconscious material. And the messages on your screen come and go much faster than you can talk about them.

- You can’t automatically believe what’s on your screen. A little skepticism is a healthy thing. Check things out. Ask around. You may be able to become 99 percent sure about what’s on your screen, but you can never be 100 percent sure. On the other hand, you shouldn’t be so suspicious that you don’t believe anything you see or hear. That is the road to alienation, conspiracy theories, and all-out paranoia.

- Your internal self-talk is a voice-over commentary on what you see on the screen. Your self-talk can contain the destructive comments of your internal pathological critic or your healthy refutations of the critic. The voice-over interprets and can distort what you see. Sometimes you are aware of the voice-over, but often you are not.

- The more distorted your screen becomes, the more certain you will be that what you see there is accurate. There is no one so sure as someone totally deluded.

- You can control some of what you see on your screen all the time. Just close your eyes or clap your hands.

- You can control all of what you see on your screen some of the time. For example, meditation can take you to a place where you are intensely aware of only one thing. Hypnosis can narrow your focus down to one thought or past event. But outside of these special states, total control is rare.

- You can’t control all of what you see all of the time.

- You can improve the quality of the picture on your screen, but you can’t get rid of the screen. Reading a self-help book like this one is a way to improve the accuracy of what you see on your screen, so is studying physics, painting a still life, asking questions, trying new experiences, or getting to know someone better. As good as your screen gets, though, you’re stuck with it. Only dead people don’t have screens.

- Critics don’t criticize you. They only criticize what they see on their screens. They may claim to see you clearly, better than you can see yourself. But they are never seeing the real you, only their screen portrait. Remember, the more adamant a critic is about the accuracy of his or her observation, the greater the chance that his or her screen image of you is distorted.

- Your perception of reality is only one of the inputs to your screen. These perceptions are colored by your inborn abilities and characteristics. Your perceptions can be influenced by your physiological or emotional state at the time. Your view of reality can be distorted or impaired by memories of similar scenes from your past, by your beliefs, or by your needs.

Let’s examine this last rule in more detail. There are many input ports, as it were, through which images may reach your screen. Only five of them have anything to do with reality—sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. And these five can be influenced or overridden by many other inputs.

For example, you see a gray-haired man with wrinkles on his face get out of a car and walk into a bank. This is what your senses tell you. Your innate constitution will determine how quickly and intensely you react to your sense impressions. If you have just had a hard time finding a parking place and you’re worried about being late for an appointment, you will be irritable and likely to make a negative judgment of everything you see. Your past experience of gray-haired, wrinkled men tells you that he is about fifty years old. Your knowledge of cars tells you that his is an expensive Mercedes. His solemn expression reminds you of your uncle Max, who has an ulcer, so you think that this man probably has an ulcer. Your past experience of banks and men’s fashion tells you that he probably has money. Your beliefs and prejudices tell you that this guy is a rich, hard-driving businessman who wrings money out of those who need it more than he does. He is probably possession-proud, since he drives an expensive Mercedes, and he’s probably unable to fully express his feelings, just like your uncle Max. Your need to feel kinder, more noble, and more caring than others leads you to rank this stranger below yourself in these important categories. You don’t like him. You feet quite critical. Given the opportunity, you might express your criticism of this unfortunate man to him. And if he suffers from extraordinarily weak self-esteem, he might agree with your snap judgment of him. And the whole exchange would be a waste of your time and his because it would have little to do with reality. It would be a result of the mishmash of observations, feelings, memories, beliefs, and needs that you had on your screen at a given moment.

Screen Inputs

In this section we will examine some of the powerful inputs, besides unadulterated reality, that can determine what you see on your screen.

Innate constitution

Certain things about everyone are genetically determined. Not just hair color, eye color, and the like, but certain behavioral tendencies appear to be established from birth. Some people are just more excitable than others. They react sooner and more vigorously to all sorts of stimuli. Some people are more nervous or quieter than others. Some people seem to require frequent social contact, while others prefer solitary pursuits. Some people are smarter or have quicker reflexes. Others are more intuitive or sensitive to fine shades of meaning or feeling. Some people adapt easily to new things, while others shun change or innovation, preferring the traditional, familiar ways. Some people are morning people, and some are night people. Some people can get along with little sleep, and others can’t function without their eight hours every night. Some people just seem naturally friendly, while others keep their distance.

These innate personality traits can easily color what people see on their screens. Night people may see a dim, gloomy world in the morning, and they are more likely at that time to be critical of others than at night, when they feel energized and ready to boogie. Loners see social functions as something to be endured, while party people see a quiet evening at home as a dreary prospect.

If someone criticizes you for being too shy and retiring, perhaps that person is innately gregarious and just can’t see that the way you present yourself is okay. Or a critic who blows up at you over little things may have been born with an irritable temper, and his outbursts may have little or nothing to do with the few small mistakes you might make.

People vary considerably in how they process outside stimulation. Some are naturally “levelers.” This means that when they see or hear something, they automatically, without thinking about it, damp down the sensation. It’s as though the brightness and volume knobs on their screens are permanently turned down. Other people are “sharpeners” who do just the opposite. Their volume and brightness controls are turned up high, so that every whisper comes across as a shout, every firecracker as a cherry bomb. Fortunately, most people are somewhere in the middle ground. Extreme levelers are in danger of becoming psychopaths because they need increasingly intense stimulation to exceed their threshold of excitement. Extreme sharpeners often become neurotic after years of being bombarded with stimuli that seem too intense and overwhelming.

In short, no matter how balanced, intelligent, or perceptive you are, you have innate, constitutional tendencies that prevent you from perceiving reality with perfect objectivity. And so no one can be a perfectly objective critic. You can only criticize what is on your screen, and that picture is not reliable. It is always a little distorted or incomplete.

Physiological state

What you see on your screen can be influenced by fatigue, headache, fever, stomachache, drugs, blood-sugar level, or any one of a hundred physiological events. You may or may not be aware of your physiological state. Even if you are aware of it, you may not notice what it is doing to your perception. And even if you do know what it is doing to your perception, you still may not be able to do anything about it.

For example, a man with an undiagnosed thyroid condition was suffering from fatigue, depression, and occasional anxiety attacks. He was alternately unresponsive and irritable with his family. At first he didn’t notice that he felt or was acting any differently than usual. His physiological state was affecting what he saw on his screen without his knowledge. When his condition was diagnosed and stabilized with medication, his critical behavior lessened. But if he forgot to take his medication, he could get very listless or jittery. At these times, he was aware of his physiological state and how it was affecting his behavior, but he couldn’t do anything about it until the medication took hold once more.

If someone often nags you, the problem could be an ulcer or a migraine, and not you at all. Your critic’s unpleasant attitude may be a result of consuming a dubious chili dog, not a result of your failure to pick up the living room.

Emotional state

When you’re really angry, you see the world through a red haze. When you are in love, the glasses change to the rose-colored variety. Depressed screens are tinted blue, and the soundtrack is uniformly gloomy. If you are what you eat, then you see and hear what you feel.

How many times have you seen this on TV? The hero works himself up into a rage, finally tells off his domineering boss or his unfaithful girlfriend, and then stomps out of the room. On the way out he encounters the office boy or the dog, to whom he screams, “And that goes for you, too!” Big laugh and dissolve to next scene.

This happens in real life too, but unfortunately without the painless dissolve to the next scene. Often you take the brunt of anger or rejection that has nothing to do with you. You are as uninvolved as the office boy or the dog. Your only fault was to be unlucky enough to encounter the critic who was still emotional about some earlier experience.

Sometimes critics are in a state of general arousal. They’re feeling tense or worried or stressed by life in general. Then you cross them in some minor or even imagined way, and they blow up. Their state of arousal is expressed as anger, and their tension is released for a while.

For example, your boss chews you out for wasting money. You bought some necessary office supplies and furniture, nothing very extravagant, and you got good prices, too. If your self-esteem is fragile, you might conclude that you lack judgment and that you will never be a success in your job. However, you might learn later that your boss had just received a financial setback and was feeling particularly paranoid about keeping expenses down. There was nothing wrong with your judgment—the blowup was caused by your boss’s free-floating state of arousal, and you became a chance opportunity for release.

Habitual behavior patterns

Everyone has coping strategies that have worked in the past and that will probably work in the future. These strategies tend to be applied automatically, regardless of the situation. For example, a child of violent parents may learn to avoid notice by not speaking up, by hiding needs, and by trying to anticipate what others want without actually asking them. These strategies will be carried over into adulthood, where they will not work very well for achieving a satisfying relationship with another adult.

Another example would be a woman who grew up in a family where an ironic, sarcastic style of humor was the norm. Outside her family circle, she often turns people off. Her habitual behavior pattern of satirizing and parodying those around her is taken as a critical, negative attitude.

Often when you feel criticized or slighted by someone, you find out later from the critic’s friends that “he’s always like that.” What they mean is that his habitual behavior patterns lead him to be critical or negative with some kinds of people in some situations, regardless of the objective reality at the time.

Everyone drags an enormous baggage of old behavior patterns around all the time. More often than not people are reaching into their bag of tricks for a familiar way of reacting, instead of basing their reaction on a fresh, accurate assessment of the situation and your role in it. They are watching old tapes on their screen instead of concentrating on the live action reported by their senses.

Beliefs

Values, prejudices, interpretations, theories, and specific conclusions about an ongoing interaction can all influence what people see on their screens. People who value neatness may exaggerate all the sloppiness they see in the world. Those who are prejudiced against blacks or Jews or Southerners cannot trust what they see on their screens concerning the groups they hate. If a man believes strongly in independence, he will tend to interpret cooperation as weakness. If a woman has a theory that all traumatic weaning causes weight problems in later life, then she will see obese people in light of her theory, not in the clear light of objective reality. If you lean back in your chair and cross your arms while talking to an insurance salesman, he may interpret that gesture as resistance to his sales pitch and redouble his efforts. His view of you on his screen will be determined by this interpretation, right or wrong. But you might have leaned back because your muscles are stiff or because you wanted to get a view of the clock.

Beliefs are tied very strongly to past experience of what life is like, what works, what hurts, and what helps. The bank officer who rejects your loan application is probably not rejecting you personally. She is responding to her past experiences of people in similar financial situations who either did or didn’t pay back their loans. The same goes for the woman who turns you down for a date. She is very likely operating out of her beliefs based on experience. She may believe that tall men are not for her, or that she must never date a Pisces, or that she must not get serious with anyone over a certain age. She is rejecting who she believes you are, not who you really are. The real you isn’t on her screen at all.

Needs

Everybody you meet is trying to get needs met all the time. This imperative affects what people see on their screens. A hungry man has a keen eye for food on the table, but might not notice a roaring fire in the fireplace or the magazines on the coffee table. A woman who feels cold, entering the room, will go straight for the fire and not notice the food or the magazines. A bored person waiting in the room would seize immediately on the magazines as a source of diversion. A thirsty person would find nothing in the room to satisfy that need and hold a lower opinion of the surroundings than the other three.

Emotional needs work the same way to distort screens and bring on criticism that has nothing to do with the actual situation. A man who wants to impress his date in a restaurant might be quite critical about the food and complain about the service, when in fact both are excellent. A less obvious case is that of the guy who is quite belligerent about asking you for your help because he has a strong need to be in control of every situation. Another subtle example is an acquaintance who is often very catty about other people’s appearance as a result of her own need to be constantly reassured about her own physical attractiveness.

Criticism that is out of proportion to the occasion is often motivated by some hidden agenda. The critic shames you into doing something that you wouldn’t do if you knew the real reason behind it. For example, let’s say that your boss asks you to stay overtime or work on the weekend and then becomes very critical when you turn him down. His request and reaction make no sense to you—there just isn’t enough work to do to justify the inconvenience. The real situation may be that your boss is just trying to impress his boss by saying that he had staff in over the weekend or that he needs you there to receive an important phone call, and he’s too lazy to come in and wait for it himself. There could be several hidden agendas, none of them having anything to do with your job or your performance.

Sometimes critics are fully aware of the emotional needs or hidden agendas that motivate them, and sometimes they’re not. But since you’re the person on the receiving end of the criticism, their awareness doesn’t matter to you. All that matters to you is recognizing that needs distort a critic’s perception of reality, and therefore no criticism can be taken at face value.

Exercise

Go around for the rest of the day or all day tomorrow imagining that your eyes are a camera. Your ears are microphones. Be the director of a documentary. Consciously compose a voice-over commentary on what you see and hear. Shift your attention to emphasize the negative or positive aspects of a scene. When someone says something to you, pretend that both of you are characters in a soap opera. Imagine several possible responses besides the one you would normally give. Imagine several possible motivations for what other people do besides the motives you assume are correct. Notice how this distancing exercise changes your awareness of reality. It should make you realize that there are many more possible ways to see reality than the one you usually use. It should also point out how automatic and limited your usual perception of the world is.

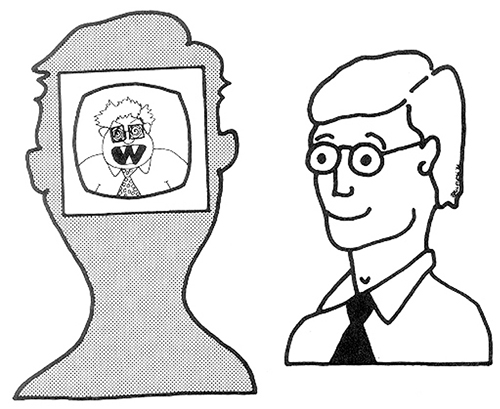

The Screen as Monster-Maker

The figure below reflects a simple, everyday encounter. The reality is simple and blameless: two men meet at a party. The man in glasses asks a newcomer what he does for a living, trying to make conversation and put him at ease. The newcomer is here with his wife. These are his wife’s friends, not his. He’d rather be at home watching the ball game or drinking beer with his buddies. He hates this sort of party and didn’t want to come in the first place. He thinks most of his wife’s friends from work are stuck-up wimps who don’t know how to have a good time. All this background and his current arousal level affect what he sees on his screen, and he responds to the distorted image with a thinly veiled insult.

Inputs:

Reality: Short guy with glasses, tie, asks, “So, what do you do?”

- + Innate constitution: Warning, new encounter, be careful, expect attack.

- + Physiological state: Short of breath from running up stairs, sweaty, heart rate high.

- + Emotional state: Aroused. Irritated at being late, angry at wife for making me come.

- + Habitual behavior pattern: Take the psychological high ground. Get in the first blow and establish dominance.

- + Beliefs: Here’s another intellectual twerp in glasses and a tie. These stuck-up eggheads are always looking for a chance to put a working man down.

- + Needs: To relieve tension of anger and anxiety. To appear powerful, tough, competent.

- = Response: Loud, chest out, leaning forward into the twerp’s face: “I work for a living. What do you do?”

Mantra for Handling Criticism

The moment you hear a critical remark, ask yourself, “What’s on this person’s screen?” Immediately assume that there is at best a tenuous, indirect connection to reality. You will stand a far greater chance of being right than if you assume that all critical remarks arise from some shortcoming in yourself.

Remember that people can only criticize what’s on their screens and that their screens are not reliable. It’s very unlikely that any criticism is based on an accurate perception of you. It’s much more likely that the critic is reacting to emotions, memories, and behavior patterns that have almost nothing to do with you. Thinking poorly about yourself because of such criticism is a mistake. It’s like running scared from a little kid with a sheet over his head who pops out behind a bush and says, “Boo!” You may be startled at first and pull back, but then you laugh and think, “It’s okay; it’s nothing real.” Just so with criticism. You may feel briefly taken aback when someone criticizes you, but then you smile and say to yourself, “Boy, I wonder what’s on his screen to make him so critical of me?”

Responding to Criticism

Does all this seem a little unrealistic? Do you find yourself saying, “Wait a minute, some criticism is based on facts. Sometimes the critic is right on the money, and you have to acknowledge it. Or sometimes you need to defend yourself. You can’t just secretly smile and keep mum!”

If this is what you’re thinking, you’re right. Often you have to respond in some way to criticism. The mantra “What’s on his screen?” is just a brief, but essential, bit of first aid for your self-esteem. Remember that all criticism shares one characteristic: it is unwelcome. You didn’t invite people to dump the distorted contents of their screen on you. You may feel that you owe some critics a response, but you never owe a critic your self-esteem.

Ineffective Response Styles

There are three basic ways to go wrong in responding to criticism: being aggressive, being passive, or both.

Aggressive style

The aggressive response to criticism is to counterattack. Your wife criticizes your TV viewing habits, and you counter with a cutting remark about her affection for social media. Your husband makes a snide remark about your weight, and you counterattack by mentioning his blood pressure.

This is the “Oh yeah?” theory of how to handle criticism. Every critic is met with a hostile “Oh yeah?” attitude, and a response that varies in intensity from “How dare you even think of criticizing me?” to “Well, I may not be much, but neither are you.”

The aggressive style of responding to criticism has one advantage: you usually get people off your back right away. But this is a short-term benefit. If you have to deal again and again with the same people, they will come back at you with bigger and bigger guns. Their attacks and your counterattacks will escalate into all-out war. You will turn potentially constructive critics into destructive enemies.

Even if your aggressive counterattack succeeds in shutting a critic up for good, you have not necessarily won. If people have genuine grievances with you, they may go behind your back and use indirect means to get what they want from you. You will be the last to know what is going on.

Consistently responding to criticism aggressively is a symptom of low self-esteem. You lash out at critics because you secretly share their low opinion of you and violently resist any reminder of your shortcomings. You attack your critics to bring them down to your own level, to show that although you may not be very worthy, you are more worthy than they are.

Consistently counterattacking your critics is also a guarantee that your self-esteem will remain low. The process of attack, counterattack, and escalation means that you will soon be surrounded by critics who besiege you with evidence of your worthlessness. Even if you had some self-esteem to start with, it will be battered down in time. Furthermore, your bellicose style of relating to people who are even slightly critical of you will prevent you from forming any deep relationships.

Passive style

The passive style of responding to criticism is to agree, to apologize, and to surrender at the first sign of an attack. Your wife complains that you are getting a little overweight, and you cave in: “Yes, I know. I’m just becoming a fat slob. I don’t know how you can stand to look at me.” Your husband tells you you’re following the car ahead of you too closely, and you immediately say that you’re sorry, slow down, and promise never to do it again.

Silence can also be a passive response to criticism. You make no response to criticism that deserves a response. Your critic then continues to harass you until you provide some belated verbal reaction, usually an apology.

There are two possible advantages to the passive style of responding to criticism. First, some critics will leave you alone when they find that they arouse no fight in you. It’s not enough sport for them. Second, if you don’t make any response at all, it saves you the trouble of thinking up something to say.

Both these advantages are short-term ones. In the long term, you will find that many critics enjoy shooting fish in a barrel. They will return time and again to take potshots at you, just because they know that they can get an apology or an agreement. Your response lets them feel superior, and they don’t care whether it’s sporting at all. And even though you’re saved the trouble of thinking up a verbal response, you’ll still find that you are expending a lot of mental energy in thinking up purely mental retorts. You don’t say them, but you think them.

The real disadvantage of the passive style is that surrendering to others’ negative opinions of you is deadly to your self-esteem.

Passive-aggressive style

This style of responding to criticism combines some of the worst aspects of both the aggressive and the passive styles. When you are first criticized, you respond passively by apologizing or agreeing to change. Later you get even with your critic by forgetting something, failing to make the promised change, or engaging in some other covertly aggressive action.

For example, a man criticized his wife for not clearing out an accumulation of magazines and books. She promised to box them up for the Goodwill truck. After being reminded twice to do it, she actually did call the Goodwill and make the donation. While she was at it, she culled some old clothes from the closet, including a favorite old shirt of her husband’s. When he got angry about her giving his favorite shirt away, she apologized again, saying that she didn’t realize that it was so important to him, and if he was so fussy he could call Goodwill and handle it himself next time.

In this example, the woman was unconscious of any plot to get even. Passive aggression is often unconscious. You make understandable mistakes. Your intentions are good, but somehow you screw up one little detail. You prepare a special dinner to make amends with your girlfriend, but you forget that she hates cream sauces. You are late for an important date or buy the wrong size or put a dent in the car.

Passive aggression lowers your self-esteem twice. Your self-esteem suffers first because you have agreed with someone about your shortcomings. Then your self-esteem gets taken down another peg when you covertly strike back. You secretly hate yourself, either for being sneaky if you’re conscious of the counterattack or for being fallible if the retaliation takes the form of an unconscious mistake.

A consistently passive-aggressive response style is hard to change because it’s indirect. The vicious circle of criticism-apology-aggression is a covert guerrilla war fought deep in the underbrush. It’s very hard to break out of the circle and achieve a level of honest, straightforward communication. The passive-aggressive person ends up too scared to risk open confrontation, and the other person has had all trust and confidence destroyed by repeated acts of sabotage.

Effective Response Styles

The effective way to respond to criticism is to use the assertive style. The assertive style of responding to criticism doesn’t attack, surrender to, or sabotage the critic. It disarms the critic. When you respond assertively to a critic, you clear up misunderstandings, acknowledge what you consider to be accurate about the criticism, ignore the rest, and put an end to the unwelcome attack without sacrificing your self-esteem.

There are three techniques for responding assertively to criticism: acknowledgment, clouding, and probing.

Acknowledgment. Acknowledgment means simply agreeing with a critic. Its purpose is to stop criticism immediately, and it works very well.

When you acknowledge criticism, you say to the critic, “Yes, I have the same picture on my screen. We are watching the same channel.”

When someone criticizes you and the criticism is accurate, just follow these four simple steps:

- Say, “You’re right.”

- Paraphrase the criticism so that the critic is sure you heard him or her correctly.

- Thank the critic if appropriate.

- Explain yourself if appropriate. Note that an explanation is not an apology. While you are working on raising your self-esteem, the best policy is never to apologize and seldom explain. Remember that criticism is uninvited and unwelcome. Most critics don’t deserve either an apology or an explanation. They will have to be satisfied with being told they’re right.

Here’s an example of responding to criticism with a simple acknowledgment:

Criticism: I wish you’d be more careful with your things. I found your hammer lying in the wet grass.

Response: You’re right. I should have put that hammer away when I was through using it. Thanks for finding it.

This is all that needs to be said. No explanation or apology or pledge to reform is needed. The respondent acknowledges a minor lapse, thanks the critic, and the case is closed. Here is another example of simple acknowledgment:

Criticism: You almost ran out of gas on the way to work this morning. Why didn’t you fill the tank yesterday? I don’t see why I always have to be the one who does it.

Response: You’re right. I noticed we were low on gas, and I should have gotten some. I’m really sorry.

In this example, the respondent has caused the critic some real inconvenience and adds a sincere apology. Here’s another example of a case where some explanation is in order:

Criticism: It’s nine thirty. You should have been here half an hour ago.

Response: You’re right; I’m late. The bus I was on this morning broke down, and they had to send out another one to pick us all up.

Advanced acknowledgment involves turning a critic into an ally. Here’s an example:

Criticism: Your office is a mess. How do you ever find anything in here?

Response: You’re right; my office is a mess, and I can never find what I want. How do you think I could reorganize my filing system?

Exercise

After each of the following criticisms, write your own response using the full “you’re right, paraphrase, explain” formula.

Criticism: This is the sloppiest report I’ve ever seen. What did you do, write it in your sleep?

Response:

Criticism: Your dog dug a giant hole under our fence. Why can’t you keep it under control?

Response:

Criticism: When are you going to return those books to the library? I’m sick of asking you. You’ve promised to do it twice now, and they’re still sitting on the hall table.

Response:

Acknowledgment has several advantages. It is always the best strategy for quick and effective deflation of critics. Critics need your resistance in order to keep hassling you. They want to fully develop their theme, hitting you time after time with examples and restatements of your failings. When you agree with a critic, you go with the force of the blow, as in judo. The criticism is harmlessly expended on empty air. The critic is left with nothing more to say, since your refusal to argue has made further talk unnecessary. Very few critics will persist after acknowledgment. They get the satisfaction of being right, and that is worth being denied the luxury of raking you over the coals at length.

Acknowledgment has one big disadvantage: it doesn’t protect your self-esteem if you acknowledge something that isn’t true about yourself. Acknowledgment only works to protect your self-esteem when you can sincerely agree with what a critic is saying. When you can’t agree fully, you are better off using the clouding technique.

Clouding. Clouding involves a token agreement with a critic. It is used when criticism is neither constructive nor accurate.

When you use clouding to deal with criticism, you are saying to the critic, “Yes, some of what is on your screen is also on my screen.” But to yourself you add, “And some isn’t.” You “cloud” by agreeing in part, in probability, or in principle.

- Agreeing in part. When you agree in part, you find just one part of what a critic is saying and acknowledge that part. Here is an example:

- Criticism: You’re not reliable. You forget to pick up the kids, you let the bills pile up until we could lose the roof over our head, and I can’t ever count on you to be there when I need you.

- Response: You’re certainly right that I did forget to pick up the kids last week after their swimming lesson.

In this example, the blanket statement “you’re unreliable” is too global to agree to. The charge that they will lose the roof over their heads is an exaggeration, and the “I can’t ever count on you” just isn’t true. So the respondent picks one factual statement about not picking up the kids and acknowledges that.

Here is another example of clouding by agreeing in part:

- Criticism: Miss, this is the worst coffee I’ve ever had. It’s weak and watery and barely warm. I heard good things about this place—I hope the food is better than the coffee.

- Response: Oh, you’re right; it’s cold. I’ll get you another cup from a fresh pot right away.

In this example, the waitress finds one objective truth that she can agree with and ignores the other complaints.

- Agreeing in probability. You agree in probability by saying, “It’s possible you’re right.” Even though the chances may, in your mind, be a million-to-one against it, you can still honestly say that it’s possible. Here are a couple of examples.

- Criticism: If you don’t floss your teeth, you’ll get gum disease and be sorry for the rest of your life.

- Response: You may be right. I could get gum disease.

- Criticism: Riding the clutch like that is terrible for the transmission. You’ll need an overhaul twice as quick. You should just let it out and leave it alone.

- Response: Yes, I may be doing the wrong thing here.

These examples show the essence of clouding. You are appearing to agree, and the critic can be satisfied with that. But the unspoken, self-esteem-preserving message is “Although you may be right, I don’t really think that you are. I intend to exercise my right to my own opinion, and I’ll continue to do just as I damn well please.”

- Agreeing in principle. This clouding technique acknowledges a critic’s logic without necessarily endorsing all of a critic’s assumptions. It uses a conditional “if…then” format:

- Criticism: That’s the wrong tool for the job. A chisel like that will slip and mess up the wood. You ought to have a gouge instead.

- Response: You’re right; if the chisel slips, it will really mess up the wood.

The respondent is admitting the logical connection between tools slipping and damage to the work, but has not actually agreed that the chisel is the wrong tool. Here is another example:

- Criticism: You’re really taking a chance by claiming all these deductions you don’t have receipts for. The IRS is really cracking down. You’re just asking for an audit. It’s stupid to try to save a few bucks and bring them down on you like a pack of bloodhounds.

- Response: You’re right; if I take the deductions, I’ll be attracting more attention to myself. And if I get audited, it will be a real hassle.

- This response agrees with the critic’s logic without agreeing with the critic’s assessment of the degree of risk.

Exercise

In the space after the following three critical statements, write your own responses. To each criticism, agree in part, in probability, and in principle.

Criticism: Your hair is a fright. It’s dry and frizzy, and it must be months since you had it cut. I hope you’re not going out in public like that. If you do, people will be laughing behind your back. How can you expect people to take you seriously when you present yourself to the world like that?

Agree in part:

Agree in probability:

Agree in principle:

Criticism: You spend all your money on appearances: your clothes, your apartment, your car. How things look is all that matters to you—keeping up a good front. How do you expect to handle any emergencies if you never save anything? Suppose you got sick, suppose you lost your job? It just makes me sick seeing you squandering every dime you make.

Agree in part:

Agree in probability:

Criticism: Is this the best you can do? I wanted an in-depth analysis, and this just hits the high points. This report should be twice as long, with discussion of all the points I raised in my memo. If we turn this in to the planning department, they’ll just toss it back. You need to try it again, and put a little thought into it.

Agree in part:

Agree in probability:

Agree in principle:

The advantage of clouding in its various forms is that it quiets critics without sacrificing your self-esteem. The critics hear the magic message “you’re right” and are satisfied with that. They don’t notice or don’t care that you have said that they are only partly right, probably right, or right in principle.

Sometimes it’s hard to content yourself with a clouding response. You may feel compelled to give voice to your real, fully developed opinions and feelings on the subject. It’s tempting to argue and attempt to win the critic over to your point of view. This is all right if the criticism is constructive and the critic is amenable to a change of viewpoint. But most criticism with which you disagree isn’t worth dignifying with an argument. You and your self-esteem are better off clouding the issue with a token agreement and then changing the subject.

You may feel guilty when you first try clouding. It may seem sneaky and manipulative. If that’s the case, remember that you don’t owe anything to a critic. Criticism is unwelcome and uninvited. Criticism is often a sign of critics’ basic negativity and insecurity: they have to harp on what’s wrong with life instead of enjoying the positive side. They have to tear you down in order to bolster themselves up. Most critics are manipulative themselves: rather than directly ask you to do something, they try to influence you indirectly by complaining about you. Especially when criticism is incorrect or not constructive, you are perfectly within your rights to be just as manipulative as the critic. Your self-esteem comes first.

The only disadvantage of clouding is that you may use the technique too soon. If you don’t understand the critic’s motives or message fully and you use clouding to cut the exchange short, you may miss hearing something beneficial. Before jumping in with your clouding response, make sure that you understand what is being said and determine if the critic is trying to be constructive. If you can’t tell exactly what the critic means, use probing.

Probing. A lot of criticism is vague. You can’t tell what the critic is driving at. You must use probing to clarify the critic’s intent and meaning. When you have uncovered the full message, then you can decide if it is constructive, if you agree with all or part of it, and how you will respond.

By probing, you are saying to your critic, “Your screen’s not clear to me. Could you adjust the focus, please?” You keep asking the critic to clarify until you have a good picture. Then you can say, “Oh yes, I have the same channel on my screen” or “Well, yes, some of what you have on your screen is also on mine (and some isn’t).”

Key words for probing are “exactly,” “specifically,” and “for example.” Here are some typical probes: “How exactly have I let you down?” “What specifically bothers you about the way I do the dishes?” “Can you give me an example of my carelessness?”

“Oh yeah?” “Prove it!” and “Says who?” are not examples of proper probing. You should keep your tone inquisitive and nonargumentative. You want further information, not a fight.

When you are probing a nagger, it’s helpful to keep asking the nagger for examples of the behavior change he or she wants you to make. Insist that the complaint be put in the form of a request for a change in your behavior. Lead your critic away from abstract and pejorative terms such as “lazy,” “inconsiderate,” “sloppy,” “grouchy,” and so on. Here is an example of probing a nagger:

He: You’re lazy.

She: Lazy how, exactly?

He: You just sit around.

She: What do you want me to do?

He: Stop being such a slug.

She: No, really, I want to know what you’d like me to do.

He: Well, clean out the basement, for one thing.

She: And what else?

He: Stop playing with your smartphone all day.

She: No, that’s what you don’t want me to do. What actual things do you want me to do instead?

This approach forces the nagger away from name-calling and vague complaining toward some real requests that you can seriously consider. It directs the focus away from a recitation of past sins and toward the future, where the possibility of change exists.

Exercise

For each of the following three vague criticisms, write your own probing responses.

Criticism: You’re not pulling your weight around here.

Criticism: You’re so cold and distant tonight.

Criticism: Why do you have to be so stubborn? Why can’t you give a little?

The advantages of probing are obvious. You get the information you need to figure out how to respond to a critic. You may find that what sounded like criticism at first was actually a reasonable suggestion, an expression of concern, or a cry for help. At its best, clarifying your critic’s message can turn a casual complaint into a meaningful dialogue. At worst, probing a critic will confirm your suspicion that he or she is maliciously attacking you and therefore deserves your most adroit clouding tactics.

The only disadvantage of probing is that it is an interim tactic. It just clears up your understanding of the critic’s intent and meaning. You still have to choose whether to acknowledge the criticism or to use one of the forms of clouding. The decision tree in the next section will help you review which responses to make based on your probing.

Putting It All Together

The first part of this chapter taught you what to do the moment you first suspect that you are hearing something critical: Apply your mantra, “What’s on the screen?” Remind yourself that the critic is only being critical of the content of his or her screen, not of reality. It has nothing to do with you directly. Resist the automatic agreement of your own internal pathological critic. Tell yourself to take your self-esteem out of the circuit.

Once you have your self-esteem out of the circuit, you can concentrate on what the critic is actually saying. Listen first for the critic’s intention. Hear the tone. Consider the situation and your relationship to the critic. Is the criticism constructive? Is the critic trying to help or hassle?

Look at the decision tree in figure 4. It shows all the possible appropriate, assertive, high self-esteem responses you can make to any criticism.

If you can’t tell whether the critic means to help or hassle you, you need to use probing until the intention becomes clear. Once you have determined the intention, ask yourself if the content of the message is accurate. Do you agree with it?

If you find that criticism is meant to be constructive, but is simply inaccurate, all you have to do is point out the critic’s error, and the case is closed. If constructive criticism is accurate, all you have to do is acknowledge it, and again the case is closed. The same goes for criticism that is not constructive but happens to be completely accurate: you just agree with it and spike the critic’s guns.

The only case that is left is the one in which the critic is not constructive and not accurate. This critic not only is out to hassle you, but he or she has also got the facts wrong. This critic deserves a clouding response—agree in part, in probability, or in principle, and stop there.

Exercise

Use some examples of criticism from this chapter or from your own life. Run them through the decision tree (which is also available in printable form at http://www.newharbinger.com/33933) and see how you would respond, depending on what is constructive and what is accurate.