Epilogue

The Persistence of Family Life as an Engine of Change

This book has been about home and family life and the way ordinary people managed their affairs in the nine or so millennia between the end of the Ice Age and the coming of the Romans. But it has not been a story of domestic complacency. Instead we have seen how families and communities were able to change and to organize the world around them. They established networks of communication over huge distances, and we have seen how they were able to plan and synchronize expansion and development. As a visible legacy, they bequeathed us the remarkable barrows, henges and hillforts that still adorn the British landscape. But these are mere things. To my mind, their greatest contribution was a pattern of regional cultures whose flexibility has allowed the British to play such an extraordinarily creative role on the world’s stage. If I had my way, I would organize an annual holiday in honour of the Unknown Britons.

The arrival of centralized Roman authority, first at Colchester, then soon after at London, marked a fundamental change. I still hold that it was a change ahead of its time, which would have been more appropriate in, say, the 8th and 9th centuries AD, when Middle Saxon England was beginning to trade actively with Carolingian Europe. It was then that the first successful towns began to appear, and with them came the beginnings of the modern world. But sadly, history cannot be rewritten, even to please prehistorians. So I would like to finish this book with some thoughts on how families and ordinary people continued to exert an important stabilizing influence in Roman and early medieval times. Some might see this as the final throes of prehistoric independence, but I’m less pessimistic. I believe that families and family life have continued to play a much larger role in subsequent British history than is generally appreciated. And a good example of this may be found in the social background to the diverse origins of the early Industrial Revolution.1 But that would be another book. Indeed, I would not be surprised if the development of the internet were to trigger yet another series of changes, whose roots lay ultimately in hearth and home. But now we must return briefly to those incoming Romans, and my personal views on them, which I have to confess have not always been very favourable. But again, if I were to be objective, have I been entirely fair? Surely I must concede that Classical civilization was most remarkable? And yes, it probably was, but why do people still think that change can only happen through the use of force? I would suggest that true, lasting transformation can only come from within individuals, families and societies, via education and rational argument. And to be frank, that is why I still regard the Romans in Britain with some distaste.

ROMAN, OR ROMANO-BRITISH?

When I emerged after celebrating being accepted by Cambridge, I can remember wondering what on earth I ought to be reading during the months of my gap year. So I sought advice from James Dyer, perhaps the most important pioneer of archaeological education in English schools – although I did not know that, then. To me, James was the smiling and very personable director of the excavations at Ravensburgh hillfort, high in the Dunstable Downs, not far from Luton – where I was working as a youthful volunteer. I remember he didn’t give me a reading list, but suggested various authors I should look out for when in a library or bookshop. It was a very intelligent suggestion, as it allowed me to use my own discretion. Today, things are more prescriptive: Reading Lists dominate everything and students are not encouraged to use their own judgement – nor, indeed, to make their own mistakes, which can ultimately teach even more. Anyhow, James told me to read anything by Professor Sheppard Frere, of Oxford University. The great man happened to live at Stamford and I met him several times when I was starting work in Peterborough, from 1970. Frere’s superb overview of Roman Britain appeared during my last year at Cambridge, and mindful of James’s advice, I bought a copy – and I still find myself referring to it from time to time.2 On the very first page he makes the point that there was no such thing as a truly Roman Britain, because the province of Britannia was a relative late-comer and although it was a part of the Empire for some three and a half centuries, it never became as closely integrated within the system as many contemporary provinces on the European mainland.

In recognition of this, archaeologists refer to the people, the culture and economy of Britain during the Roman period as Romano-British, or R-B for short. The time period involved (AD 43 to c. 410), is known as Roman (and never Romano-British). I usually try to steer clear of such seemingly narrow distinctions, but in this instance the difference is important; so I abide by the rules.3

Anyone with even a slight interest in Britain’s ancient history will know that the Roman period began in AD 43 with the Conquest. But it is less well known that people across quite a large area of what would later be known as south-eastern England had already adopted a more Roman-style of self-image, complete with Romanized toilet equipment (such as tweezers, fingernail cleaners, ear-wax scoops and compact pestles and mortars for grinding make-up) and large safety-pin-style fibula brooches, which were better suited to holding together the finer fabrics of Roman costume. Both the toilet equipment and the fibula brooches are first found not on early Roman sites, but in Late Iron Age contexts, towards the end of the 1st century BC and into AD – up to two generations prior to the Conquest.4 Indeed, a particularly fine pestle and mortar make-up set was found at Flag Fen.

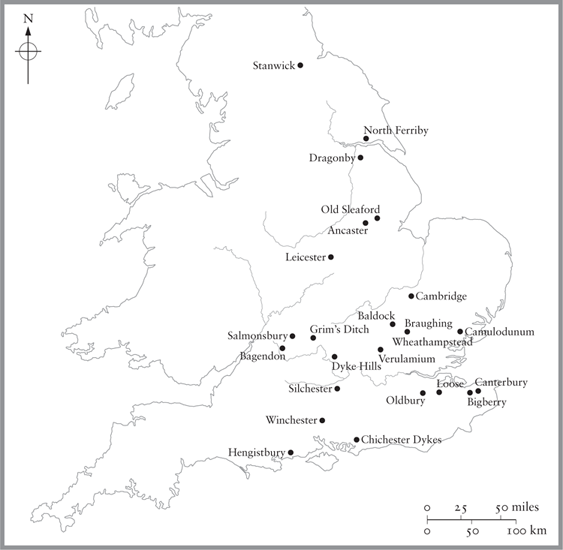

There has been much discussion as to whether the latest Iron Age communities in Britain included urban settlements, as we would understand the term today. My own feeling is that true towns were a Mediterranean concept, and that the large defended town-like settlements of pre-Roman Britain, which prehistorians of the mid-20th century labelled oppida (from oppidum, the Latin for town), are very different. They included substantial open spaces and they lacked the regular street-patterns which are such a clear indication of the strong central planning authority needed to make, and to run, a true town. They also lacked other infrastructural services, such as sewage or refuse disposal. Essentially, they were sizeable villages, but surrounded or partially protected by earthworks or other defensive structures (see Fig. 8.1). Their presence does however suggest that some British tribal kingdoms of the Late Iron Age possessed quite a well-developed hierarchical social structure.

It is interesting that the distribution of known Late Iron Age oppida coincides quite well with that of Roman villas, many of which grew and expanded in the latter part of the Roman period, in the 4th century AD (see Fig. 8.2).5 This large area comprises most of England: the south, south-east, east Midlands and Yorkshire – all but the westernmost Midlands, and the south-west, and of course most of Wales, too (with the notable exception of the south). This part of Britain is generally taken as the most Romanized region of the province of Britannia. But even here, the political systems were far from homogeneous and the populations would have been partitioned into at least eleven tribal kingdoms in, that is, the final centuries of the Iron Age. These kingdoms were used by the Roman administration as the principal sub-divisions of the new province, and were given the name civitates, which roughly translates into ‘counties’ – although in reality most were the size of two or three modern (i.e. Saxon) counties.6

Fig. 8.2 A map of Roman villas in Britain. This is taken from Millett (1990), Fig. 48; I have included both ‘certain’ and ‘probable’ examples here, as time has shown many of the latter to have been ‘certain’.

Evidence for cultural continuity from Iron Age to Roman can be found at almost every level of Romano-British society; it is likely, as we have already seen, that many of the villa owners belonged to families that had been powerful in pre-Conquest times. Again, this suggests considerable social stability, and with it continuity, over two to three centuries and several generations. The most Romanized parts of Britain were those regions that had already developed more centralized forms of tribal authority and were therefore more predisposed to accept Roman ways of top-down government. Beyond these south-eastern areas, ‘Romanization’ was less readily accepted, if at all, in parts of north-western England, most of upland Wales and the far south-west (Devon and Cornwall). Scotland, north of Hadrian’s Wall, lay outside the Empire, although it was heavily influenced, especially in southern, lowland areas. The Highlands and Islands, like much of Scandinavia, lay well beyond the reach of Rome.

The question that then arises is, to what extent was the population of southern Britain, roughly within the zone of villas, a clone of Rome; or was it something new, and different? For a start, I doubt whether the majority of the rural population were Romanized much, if at all. Most would have continued to speak Celtic languages, and everyone had Celtic names. For the first two or three generations of the Roman period, most rural people lived in wooden round-houses, in the traditional style. But eventually stone replaced wood and British round yielded to Roman rectangular.

When I first read how rectangular buildings replaced round ones in most of the ‘core’ Romanized areas of southern Britain, it rather depressed me. Instinctively, I felt that when families changed something as fundamental as the shape of their houses, then they were somehow ‘selling out’, or turning their backs on their traditional culture and way of life. Strangely, I had no trouble accepting that the more Romanized elites would build themselves courtyard villas that quite closely echoed the architectural styles of the Classical world, right down to mosaics and hypocaust (underfloor) central-heating. Somehow, what the elites did back then didn’t matter so much, just as today I don’t care if bankers and footballers build themselves vast and silly-looking mansions with enormous swimming pools and golden bath taps. They are welcome to them. But I was sad that so many ordinary, sensible Britons in Roman Britain seemed quite happy to turn their backs on over eight millennia of tradition.

Now if there is one thing that archaeologists must beware of, it’s jumping to conclusions based on obvious signs of change. And it was a trap I had fallen into. Yes, the shape of houses did change profoundly, but so too did the building materials and the new skills needed to be a builder. Stonework became more fashionable and stone more freely available, thanks to new quarries, quarrying tools and techniques. Roads were better and there was also a more highly developed market system, based around the new Mediterranean-style towns, that were now to be found over most of what was later to become England. Effective saws transformed both carpentry and woodworking, and new, larger and more efficient kilns allowed the production of cheap bricks and tiles for floors, heating ducts and roofs. Hard lime plaster and mortar appeared for the first time. The building trade was transformed and even in more outlying areas, people would mimic the new styles, but in traditional materials: wood, thatch, mud-and-stud, rather than bricks, tiles and mortar. But what I had failed to realize was that the organization of the interior of the new rectangular buildings closely echoed that of round-houses.

As we saw in the previous chapter, everything in a round-house effectively revolved around the central ‘core’, surrounding the hearth, and an outer ‘periphery’, where people ate, socialized, worked and slept, beyond the immediate heat of the fire.7 We see a near-identical core/periphery arrangement in many Roman houses and barns, which were built in a 3-aisled arrangement, with a central and two side-aisles. Indeed, a leading authority on Iron Age houses was so struck by the similarity of the spatial arrangement between traditional round-houses and the new Roman-style 3-aisle buildings, that he saw the persistence of round-houses – well into the Roman period at places like Piercebridge, in County Durham – as ‘a positive statement of cultural conservatism’.8 This should cause few surprises, given that Piercebridge was within the civitas of the Brigantes, which lay well outside the more highly Romanized area of the south-east.

Taken together, the evidence from Britain in the Roman period suggests that the Romano-British possessed a culture that had a strong identity in its own right, and was more than merely an absence of Romanitas, that is to say, of Classical influence. In fact, there can be no doubt that members of the higher echelons of R-B society would have appeared Roman, because it was in their interests to do so. They would have travelled widely and spoken Latin when required; indeed they often had Latinized British names themselves.

Post-war excavations in London and other cities have revealed a wealth of inscriptions on buildings, tombstones and suchlike, but also smaller and more informal, short-lived writing on tablets, such as ‘curses’ and wish-lists placed in springs, or offered at shrines. These were always in Latin, and it is hard to avoid the impression that the language was spoken quite widely in cities, if not in the country. I would suspect that the situation in Roman London might have been similar to that in Indian cities under the British Raj, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, where a significant proportion of the population were bilingual.

I’m sure that there would have been a social divide between the elite and the rest, but on the other hand from the late 3rd and throughout the 4th century AD, towns in Roman Britain declined at the expense of country estates, and the social implications of this are still not fully understood. It was a fascinating time, when Romano-British culture seems to have developed a unique and insular character that was recognizably Romanized, but at the same time very British. This was the so-called Golden Age of Roman Britain, and I find it hard to believe that the owners of many rural estates, whose families were, after all, British too and were raised in the area, suddenly decided to sever relations with the bulk of the population living around them. Were that the case, one might expect to find signs that villas had sprouted defences, or were being attacked, and there is little evidence for this, even towards the close of the Roman period in Britain, when the Empire and the Roman army were growing very much weaker and were under constant threat. So I’m inclined to view the changes in later Romano-British society as a sign, not so much of stress, as of communal coherence and stability. It is worth recalling here that during the late 4th century the province of Britannia was still supplying men and corn to the Roman army, although this was soon to cease.

The nominal date for the withdrawal of Roman authority from Britain is AD 410, but the process had been under way for at least twenty years, or more, prior to that. The Roman-style money-based market economy had reverted more to the earlier, Iron Age, way of doing things, where goods were exchanged, often within and between families, as part of wider social networks. Back in the first and second centuries AD, the Romans had had the good sense to found their new towns close to traditional Iron Age places of exchange and bartering. Then, and as the money-based economy fell out of use towards the end of the 4th century, many of these locations continued to be used, much as in pre-Roman times, although not necessarily as official (i.e. tax-paying) market-places. In other words, southern British society and economy were proving very good at adapting to what would have seemed like powerful global changes going on around them.

The final events of Roman Britain are fascinating. In 408 there was a major incursion by ‘barbarians’ from continental Europe. By then the Roman army was too weak and disorganized to reject these intruders from Britain. So the British elite took charge and removed them themselves. The following year, and probably as part of the same process, they removed what was left of the governing Roman bureaucracy, too. Presumably they saw little sense in continuing to pay taxes to a government and military who were incapable of looking after their interests. This revolt has traditionally been seen as led by peasants, but as the general level of upheaval seems to have been quite slight, it makes much better sense to attribute it, instead, to the existing Romano-British elite, who didn’t do it on their own and who must have collaborated closely with the rest of British society.9 In other words, it was a broadly based revolt that got rid of the creaking authority of Rome, yet retained society’s coherence and allowed Britain to survive into the post-Roman era, without too much strife and bloodshed. Indeed, recent excavations at places like York, Wroxeter and Silchester have demonstrated that while life in and around these towns may not have been the bustling ‘town-life’ of Roman times, it was prosperous nonetheless, and was enjoyed by quite substantial populations, most probably under the care and protection of the emerging Christian Church.10

ENGLAND INVENTS ITSELF (AD 450–650): THE POST-ROMAN IRON AGE?

Ever since I was a boy I have enjoyed a good mystery. But I have always been interested in unravelling, in explaining, them. I don’t share the fascination of some for those events we will never understand, like the abandonment of the Mary Celeste in 1872. Any chances of finding new evidence vanished when the ship was intentionally wrecked by its owner, as part of an insurance fraud, in 1885; when I discovered this, my childhood fascination also vanished. But the Dark Ages are very different. True, there are not many sound written sources to cover the three post-Roman centuries, but the ship of Britain (if I may over-extend a metaphor) has certainly not been wrecked, because we do have archaeology – and lots of it. In fact, I would say we now know as much about the settlements, infrastructure and economy of Early Saxon Britain as of any other period of British history, or prehistory – and I add that, not as an afterthought, but as a realistic contribution. Dominic Powlesland, a good friend over the past four decades, and a man who has made a huge contribution to our understanding of the earlier 1st millennium AD, likes to describe the period as the Post-Roman Iron Age. And as we will see very shortly, he has a wealth of evidence to back him up. But first I must introduce the period.

I very much doubt if archaeologists and historians will ever be able to eliminate that name, the Dark Ages, however much we would like to see it go. Certain terms are unlikely ever to be dislodged. The ‘Dark Ages’ were first mentioned in the 17th and 18th centuries to describe the onset of medieval darkness that was only to become ‘enlightened’ by the Renaissance of the 15th and 16th centuries. Latterly, the term has been used to describe the paucity of written sources on Britain – and hence the historical darkness – in the three centuries following the end of the Roman period. I don’t find the term remotely helpful and prefer to think of British early medieval history in three broad eras, each of roughly two centuries: Early Saxon (AD 410–650), Middle Saxon (650–850) and Late Saxon (850–1066). As all British readers will be aware, 1066 was the date of the Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest.

The Saxon period has not fared very well in the hands of historians, who have generally underplayed its significance, but it is worth noting here that a lot of the innovations popularly believed to have been introduced by the Normans had actually occurred in Saxon times. Many of Britain’s great cathedrals, for example, had Saxon origins; some of them, as at Canterbury, were vast. Saxon Benedictine monasteries, like those at Glastonbury and Peterborough, were already very prosperous before the Norman Conquest. The famous medieval system of collective farming, known as the open field system, had been widely adopted in England before 1066. Even castles, the ultimate symbols of Norman power, were being built on top of large mounds by Saxon earls (the oldest title of the established nobility). But perhaps most important of all, people in the Saxon period created the English language.

I’m not a linguist and I don’t intend to discuss the origins of the English language, but I do know that its closest modern relative is Frisian, a form of so-called ‘Low German’. English is a Germanic language, but one with many classical and other influences, including, of course, French. But how, and why, did it arise? It is quite possible that some people in Britain may have been speaking a Germanic language shortly before the Roman Conquest; as Caesar explicitly states, there was at least one limited migration to Britain from the continent, by a people he describes as the ‘Belgae’.11 Personally I very much doubt whether their influence would have survived long into the Roman period, let alone into Early Saxon times.

I think the answer lies firmly in the Roman period and with the Romano-British population, who, as we have seen, had acquired a strong identity, which doubtless grew even stronger in the post-Roman decades. There is good evidence for Romano-British contacts with the continental mainland during the 4th century, as Britain was an important supplier of grain, and men, to the Roman army. I think it natural that as the influence of Rome diminished, British society turned to its continental neighbours as part of a broader process of cultural realignment. One might wonder why southern Britain did not return to, or retain, earlier, Celtic, roots, but I would suggest that the process of forming the new Romano-British identity had gone too far for that. It would have been easier and more familiar to have turned to similar Romano-hybrid cultures on the European mainland. Of course, we will never know for sure, but I don’t think that the new Saxon-based emerging English culture and language came about through cataclysmic events, such as plague, wholesale invasion or mass-migration – and all three have been proposed. No, I would prefer to see such major changes as the result of longer-term processes of social evolution that had been under way for several centuries.

On the continent, the Early Saxon period is known as the Migration Period, because people were moving around, in the aftermath of the shrinking Western Empire. The Vikings marked the final set of migrations – and just like them, I suspect other groups would have arrived in Britain in earlier post-Roman times. But the archaeological evidence does not suggest that there was wholesale population change in the conventional way, through simple invasion and displacement. If that had happened, then over a million Celtic people from what was later to become England would have fled as refugees to Wales, Cornwall and Scotland; but there is no evidence whatsoever for this. I suspect the change from Southern Briton to English happened quite gradually and was the result of two things: a strong, well-defined Romano-British culture, combined with closer social and economic links to the near continent. It is interesting, for example, that many supposedly straightforwardly Germanic (i.e. from Angeln or Saxony) burial practices in pagan ‘Saxon’ graves in East Anglia can be shown on close analysis to be subtly different from what was happening across the North Sea: the items used are identical or very similar, but they were placed and arranged in the grave in a different, and presumably British, fashion.12

The results of scientific analyses of DNA evidence are starting to throw new light on the composition and origin of the English population in the Saxon period, but as we noted in Chapter 3, this is still a relatively new subject and liable to change. There is, however, firm evidence for the arrival of new people in eastern England at this time. We are not talking about mass-migration, so much as a significant influx. Interestingly, genetic links with people in Angeln can clearly be seen in the counties around the Wash, which ties in well with those graves in East Anglia; but given the subtle changes in the way the ‘foreign’ objects were arranged in the graves, this might suggest that the newcomers had settled into existing social groups who had already modified continental practices. In other words, this limited ‘invasion’ was not necessarily hostile, and even in the region around the Wash (where the concentration of continental DNA was the highest in England), it amounted to no more than 9–15 per cent of the population.13 Stephen Oppenheimer reckons that the average figure for England as a whole was about 5.5 per cent. To put these figures into some kind of perspective, estimates of current immigration into Lincolnshire, largely based on National Insurance Numbers allocated to overseas nationals, suggests there were some 45,000 migrants in 2010/11, out of a total county population of 713,665.14 This would suggest that in one year alone, the Lincolnshire population increased by 6.3 per cent, due to immigration. The Saxon figure is the total spread over a very much longer period – maybe a century or more, giving an annual rate of well under 1 per cent. Although today, in towns like Boston and Peterborough, where numbers of migrants are high, some tensions have emerged, local communities are already working to accept the new residents, who are themselves adapting to local ways. Indeed, relations have improved hugely over the past two or three years – and I can speak from personal experience, as I live in the heart of the Lincolnshire Fens, where most of the immigrant workers earn their living.

The way the post-Roman cultural changes happened will, I think, be worked out in the next decade or two, and our understanding of the various processes will certainly be greatly aided by detailed studies of DNA and stable isotope analyses – a technique that can produce surprises, as we saw in the case of the Amesbury Archer. Science, however, is unlikely to answer why these changes occurred, and again, I’m in no doubt they were not the result of a single, or indeed a series of, top-down decisions. I suspect that with the rapid decline of the Roman Empire, the Romano-British of southern Britain were spontaneously seeking new identities. Maybe we can see evidence for changes in attitude towards outsiders in what has been termed an Anglo-Saxon ‘presence’ in Britain well into the Roman period; this was, moreover, long before the Empire would have been showing any signs of military or political weakness.15 Without further coordinated research, we cannot state positively whether these were early indications of changes that were really happening, or were merely a coincidence; but I suspect the former.

Very often in prehistory, and in archaeology, we can throw light on wider interpretive problems by ‘drilling down’ to the detail, as we saw earlier at Durrington Walls and Flag Fen. Sometimes the answers to quite difficult questions suddenly become apparent. I can recall there was a huge debate in the 1950s and ’60s about the extent to which the many changes observable in British Iron Age culture could be attributed to innovation brought about by ‘invaders’ from the continental mainland. These ideas were strongly backed by no less an authority than Christopher Hawkes, Professor of Archaeology at Oxford University.16 I remember reading about his suggestions – which amounted to a fresh invasion every few generations – and coming to the conclusion that the whole of southern Britain would have resembled Heathrow in mid-August. These ideas could not be demolished by citing common sense, but by looking at certain sites in detail, where the evidence showed no sign of any change during one of Hawkes’s periods of ‘invasion’. In fact, the quite widely accepted idea of incursions of Celtic newcomers early in the Iron Age was firmly rejected when detailed studies – including projects like our own at Fengate and Flag Fen – showed clear evidence for continuity and none for change of population. Using the same argument, it seems to me that our best chance of understanding what was going on in the Early Saxon period lies not so much in grand ideas of social realignment and changing identities, enjoyable as these can be, but in detailed analysis of information out there, in the trenches. And when it comes to the Saxon period, nobody understands its landscapes better than Dominic Powlesland, who has lived in, surveyed, excavated and closely analysed the country around West Heslerton, in North Yorkshire, continuously since the later 1970s.

The landscape in question is almost within sight of Star Carr, that remarkable post-Glacial settlement with which I opened this book. Both are positioned in the Vale of Pickering, but the later landscapes of West Heslerton are towards the southern edge of the Vale, extending up the lower slopes of the most northern of the Yorkshire Wolds. Dominic and his team have pioneered techniques of remote-sensing and geophysical survey that have allowed them to construct detailed plans of a huge area (almost 10 miles across) along the southern margins of the Vale. They were also pioneers of digital archaeology and have an excellent website.17 Their best-known discovery was the so-called ‘Ladder Settlements’, which began in later prehistoric times and flourished in the Iron Age and Roman period.18 They were given the name because of their distinctive shape when seen from the air: a series of routes and droveways linking the ‘rungs’ that were the boundary ditches of farms and settlements, each one of which had its own cemetery.

To date, the Ladder Settlements have been found in line extending for over 9 miles. These settlements and cemeteries were continuously used and occupied for over a millennium, but the very latest inhabitants, in the 4th and 5th centuries AD, had already adopted Anglo-Saxon houses (distinctive structures, with underfloor cellars, otherwise known as SFBs, or Sunken Floor Buildings), pottery and burial rites. Dominic is firmly of the opinion that these people were not invaders from outside as they occupied precisely the same settlements as their immediate R-B predecessors; their graves in the cemeteries, like those of the Roman period in general, honour those of the Iron and Bronze Ages. Again, this isn’t what one would expect of unwanted newcomers. As time passed, and as conditions in the Vale altered, the settlement pattern shifted, but again continuity is evident: certain routes and field boundaries continued to be respected. There was absolutely no evidence for disjunction or conflict – hence Dominic’s deliberate use of the term ‘post-Roman Iron Age’ to describe the period.

The biggest surprise, however, came when they carried out a survey on bodies from the West Heslerton cemetery.19 The technique used was stable isotope analysis, which I have already mentioned. This process can determine from tooth enamel whether a person grew up in the same area where he or she was buried. The results from eight prehistoric graves showed that all bodies probably came from North Yorkshire. This was what had been expected. But the samples from the earliest Anglo-Saxon (Anglian, in actual fact) graves were surprising. The artefacts found in the graves were all typical of what one might expect to find in the Angeln heartlands, around the southern Baltic and Jutland region. Indeed, any visiting authority on the subject might well have declared that these were the bodies of pioneering Anglian warriors, from overseas. Twenty-four bodies were analysed and of these, just four proved to have been from the continent. But were these the warriors? No, far from it. In fact they were female and one of them was a juvenile. Even more peculiar, none of them (to judge by the possessions buried with them) was particularly well off; so ideas of ‘high-status wives’ from overseas don’t apply, either. And what about the remaining twenty bodies: where did they come from? And again, there were more surprises: ten were local, but the others all came from west of the Pennines – which would suggest that even in the depths of the so-called ‘Dark Ages’, the infrastructure of northern England was in a good state and people could move around with ease. So this does not agree remotely with conventional notions of post-Roman Britain, which supposedly ‘reverted’ to dark forest and muddy, rutted trackways.20

Towards the end of the Early Saxon period, Dominic’s ‘post-Roman Iron Age’ societies of south-eastern Britain had developed into the early Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, much as they had done in late pre-Roman times. The best known of these early rulers is King Raedwald, who died around 625 and was ruler of Essex (the East Saxons). He is well known today, not for any particularly great deeds, but for his fabulously wealthy tomb in a ship beneath a great mound at Sutton Hoo, in Suffolk. We now know – thanks to a recent discovery at Prittlewell – that very rich burials were not confined to royalty in the emerging Kingdom of Essex. I can remember being very forcibly struck by the similarity of the arrangement of the Prittlewell tomb with another very rich and possibly ‘royal’ burial, this time from the Late Iron Age (15–10 BC), beneath the huge mound of the Lexden Tumulus, on the outskirts of Colchester. The closely similar arrangement of the two tombs surely suggests that the early Saxon kingdoms were essentially a reinvention of a much earlier tradition, which was put on hold, as it were, during the Roman period.21

That earlier tradition was, of course, tribal, and was therefore embedded within a family structure. Indeed, there is no other way that such close continuity can be explained. But these rich Saxon graves, with their lavish use of imported wine and of exotic objects, would not have seemed out of place in the Iron Age: Lexden was by no means unique. Others have been found, for example at Welwyn, in Hertfordshire, and at Snailwell, Cambridgeshire.22 Earlier examples in broadly the same tradition can be found as far north as East Yorkshire, where they date back to the late 5th century BC.23

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that wealth in Saxon Britain, like today, was mostly confined to the south-east, as the recent discovery of the breath-taking Staffordshire Hoard so vividly illustrates.24 The process we are witnessing here began to gather pace in the later Iron Age and might best be described as the centralization of power, and with it, wealth. But it would be unwise to view this as a simple process, because it was embedded within many centuries of tradition, custom and practice, all of which were ultimately based on tribe, clan and family structure. As we have seen throughout this book, it was these structures that provided the checks and balances necessary for the regulation of any system of governance. But what I find truly remarkable is that they still persist and affect the lives of everyone living in Britain today.