Chapter 1. Building Web Apps with WordPress

This book will help you build anything with WordPress: websites, themes, plugins, web services, and web apps. We chose to focus on web apps because you can view them as super websites that make use of all of the techniques we will cover.

There are many people who believe that WordPress isn’t powerful enough or meant for building web apps; we’ll get into that more later on. We’ve been building web apps with WordPress for many years and know that it’s absolutely possible for you to use it to build scalable applications.

In this chapter, we start by defining what web app’s are and then cover why WordPress is a great framework for building them. We also describe some situations in which using WordPress wouldn’t be the best way to build your web app.

What Is an App?

We like the Wikipedia definition: “Application software (app for short) is software designed to perform a group of coordinated functions, tasks, or activities for the benefit of the user.”

What Is a Web App?

A web app is just an app run through a web browser.

Note that with some web apps, the browser technology is hidden—for example, when you’re integrating your web app into a native Android or iOS app, running a website as an application in Google Chrome, or running an app using Adobe AIR. However, inside these applications, there is still a system parsing HTML, CSS, and JavaScript.

You can also think of a web app as a website, plus more application-like stuff. There is no exact dividing line where a website becomes a web app. It’s one of those cases where you just know it when you see it.

What we can do is explain some of the features of a web app, give you some examples, and then try to come up with a shorthand definition so that you know generally what we are talking about as we use the term throughout the book.

Note

You will see references to SchoolPress while reading this book. SchoolPress is a web application we are building to help schools and educators manage their students and curricula. All of the code examples are geared toward functionality that may exist in SchoolPress. We talk more about the overall concept of SchoolPress later in this chapter.

Features of a Web App

The following are some features typically associated with web apps and applications in general. The more of these features there are in a website, the more appropriate it is to upgrade its label to a web app.1

- Interactive elements

-

A typical website experience involves navigating through page loads, scrolling, and clicking hyperlinks. Web apps can have links and scrolling, too, but they tend to use other methods of navigating through the app.

Websites with forms offer transactional experiences. An example would be a contact form on a website or an application form on the careers page of a company’s career website. Forms allow users to interact with a site using something more than a click.

Web apps will have even more interactive user interface (UI) elements. Examples include toolbars, drag-and-drop elements, rich text editors, and sliders.

- Tasks rather than content

-

Remember, web apps are “designed to help the user to perform specific tasks.” Google Maps users get driving directions. Gmail users write emails. Trello users manage lists. SchoolPress users comment on class discussions.

Some apps are still content focused. A typical session with a Facebook or Twitter app involves about 90% reading. However, the apps themselves present a way of browsing content different from the typical web browsing experience.

- Logins

-

Logins and accounts allow a web app to save information about its users. This information is used to facilitate the main tasks of the app and enable a persistent experience. When logged in, SchoolPress users can see which discussions are unread. They also have a username that identifies their activity within the app.

Web apps can also have tiers of users. SchoolPress will have administrators controlling the inner workings of the app, teachers setting up classes, and students participating in class discussions.

- Device capabilities

-

Web apps running on your phone can access your camera, your address book, internal storage, and GPS location information. Web apps running on the desktop may access a webcam or a local hard drive. The same web app might respond differently depending on the device accessing it. Web apps will adjust to different screen sizes, resolutions, and capabilities.

- Work offline

-

Whenever possible, it’s a good idea to make your web apps work offline. Sure, the interactivity of the internet is what defines that “web” part of web app, but a site that still works when you drive through a tunnel will feel more like an app.

With Gmail, you can draft emails offline. Evernote allows you to draft notes offline and then synchronize them to the internet when connectivity is restored.

- Mashups

-

Web apps can tie one or more web apps together. A web app can utilize various web services and APIs to push and pull data. You could have a web app that pulls location-based information like longitude and latitude from Twitter and Foursquare and posts it to a Google Map.

Mobile Apps

Since the first edition of this book was published back in 2012, web apps—and mobile apps in particular—have taken off. On most websites, mobile devices have now overtaken desktop computers as the largest source of traffic (Source: Perficient, Inc.).

In 2012, the quintessential web app looked something like Basecamp, project management software accessed through your desktop web browser. In 2019, the quintessential web app looks like Twitter, a communication app accessed through your iOS or Android phone.

Because in most cases, the majority of your users will be accessing your websites and apps on a mobile device, we support a “mobile first” mindset when designing and developing web apps. We cover how to get your WordPress apps running natively on mobile in Chapter 16. We cover the basics of responsive design and having your websites show up properly for any screen size in Chapter 4.

Progressive Web Apps

Progressive web apps (PWAs) are websites that take advantage of modern browser features to behave as native apps in Android, iOS, or on the desktop. Specifically, websites that use service workers to function while offline have a web app manifest file to define the app to the operating system (OS), and meet a few other requirements so they can be launched as apps directly from the browser.

PWAs have been championed by the Google Chrome team, but are now supported on iOS and most modern web browsers. A feature plugin for PWA support is in development to support the primary features of PWAs in WordPress core. You can use this plugin turn your WordPress site into a PWA, and that is a good idea, but in reality coding a PWA is more of a mindset than a simple conversion. Similar to the “features of a web app” we just described, the main PWA site at Google has a checklist of features expected for most PWAs, including these baseline features:

-

Site is served over HTTPS.

-

Pages are responsive on tablets and mobile devices.

-

All app URLs load while offline.

-

Metadata is provided for Add to Home screen.

-

First load is fast even on 3G.

-

Site works cross-browser.

-

Page transitions don’t feel like they block on the network.

-

Each page has a URL.

In addition to the baseline features, there is a checklist of items for “exemplary” PWAs that covers user experience (UX) and performance. Google’s Lighthouse tool provides automated tests and reports for meeting the PWA criteria. Even fully native apps or apps built for the browser can benefit from some of the suggestions in the PWA checklists and Lighthouse reports.

Why Use WordPress?

No single programming language or software tool will be right for every job. We’ll explore why you may not want to use WordPress in a bit, but for now, let’s go over some situations in which using WordPress to build your web app would be a good choice.

You Are Already Using WordPress

If you already use WordPress for your main site, you might be just a quick plugin away from adding the functionality you need. WordPress has great plugins for ecommerce (WooCommerce), forums (bbPress), membership sites (Paid Memberships Pro), social networking functionality (BuddyPress), and gamification (BadgeOS).

Building your app into your existing WordPress site will save you time and make things easier on your users. So, if your application is fairly straightforward, you can create a custom plugin on your WordPress site to program the functionality of your web app.

If you are happy with WordPress for your existing site, don’t be confused if people say that you need to upgrade to something else to add certain functionality to your site. It’s probably not true. You don’t need to throw out all the work you’ve already done on WordPress, and what follows are great reasons to stick with WordPress.

Content Management Is Easy with WordPress

Developed first as a blogging platform, WordPress has evolved through the years, and with the introduction of custom post types (CPTs) in version 3.0, into a fully functional content management system (CMS). Any page or post can be edited by administrators via the dashboard, which can be accessed through your web browser. You will learn about working with CPTs in Chapter 5.

WordPress makes adding and editing content easy via a WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) editor, so you don’t have to use web designers every time you want to make a simple change to your site. You can also create custom menus and navigation elements for your site without touching any code.

If your web app focuses on bits of content (e.g., our SchoolPress app is focused on assignments and discussions), the Custom Post Types API for WordPress (covered in Chapter 5) makes it easy to quickly set up and manage this custom content.

Even apps that are more task oriented will typically have a few pages for information, documentation, and sales. Using WordPress for your app will give you one place to manage your app and all of your content.

User Management Is Easy and Secure with WordPress

WordPress has everything you need for adding both administrative users and end users to your site.

In addition to controlling access to content, the Roles and Capabilities system in WordPress is extensible and allows you to control what actions are available for certain groups of users. For example, by default, users with the contributor role can add new posts, but can’t publish them. Similarly, you can create new roles and capabilities to manage who has access to your custom functionality.

You can use plugins like Paid Memberships Pro to extend the built-in user management to allow you to designate members of different levels and control what content users have access to. For example, you can create a level to give paying members access to premium content on your WordPress site.

Plugins

There are more than 55,000 free plugins in the WordPress repository. There are many more plugins, both free and premium, on various sites around the internet. When you have an idea for an extension to your website, there is a good chance that there’s a plugin for that, which will save you time and money.

There are a handful of indispensable plugins that we end up using on almost every site and web application we build.

For most websites you create, you’ll want to cache output for faster browsing, use tools like Google Analytics for visitor tracking, create sitemaps, and tweak page settings for search engine optimization (SEO), along with a number of other common tasks.

There are many well-supported plugins for all of these functions. We suggest our favorites throughout this book; you can find a list of them on this book’s website.

Flexibility Is Important

WordPress is a full-blown framework capable of many things. Additionally, WordPress is built on PHP, JavaScript, and MySQL technology, so anything you can build in PHP/MySQL (which is pretty much anything) can be bolted into your WordPress application easily enough.

WordPress and PHP/MySQL in general aren’t perfect for every task, but they are well suited for a wide range of tasks. Having one platform that will grow with your business can allow you to execute and pivot faster. For example, here is a typical progression for the website of a Lean startup running on WordPress:

-

Announce your startup with a one-page website.

-

Add a form to gather email addresses.

-

Add a blog.

-

Focus on SEO and optimize all content.

-

Push blog posts to Twitter and Facebook.

-

Add forums.

-

Use the Paid Memberships Pro plugin to allow members to pay for access.

-

Add custom forms, tools, and application behaviors for paying members.

-

Update the UI using JavaScript techniques and frameworks.

-

Tweak the site and server to scale.

-

Localize the site/app for different countries and languages.

-

Add Progressive Web App support.

-

Launch iOS and Android wrappers for the app.

The neat thing about moving through this path is that at every step along the way, you have the same database of users and are using the same development platform.

Frequent Security Updates

The fact that WordPress is used on millions of sites makes it a target for hackers trying to break through its security. Some of those hackers have been successful in the past; however, the developers behind WordPress are quick to address vulnerabilities and release updates to fix them. It’s like having millions of people constantly testing and fixing your software, because that’s exactly what is happening.

The underlying architecture of WordPress makes applying these updates a quick and painless process that even novice web users can perform. If you are smart about how you set up WordPress and upgrade to the latest versions when they become available, WordPress is a far more secure platform for your site than anything else available. We discuss security in more detail in Chapter 8.

Cost

WordPress is free. PHP is free. MySQL is free. Most plugins are free.

Servers and hosting cost money, but depending on how big your web application is and how much traffic you get, it can be relatively inexpensive. If you require custom functionality not found in any existing plugins, you may need to pay a developer to build it. Or if you are a developer yourself, it will cost you some time.

Responses to Some Common Criticisms of WordPress

Some highly vocal critics of WordPress might say that it isn’t a good framework for building web apps, or that it isn’t a framework at all. With all due respect to those with these opinions, we’d like to go over why we disagree. The following are some common criticisms.

WordPress is just for blogs

Many people believe that because WordPress was first built to run a blog, it is good only for running blogs.

Statements like this were true a few years ago, but WordPress has since implemented strong CMS functionality, making it useful for other content-focused sites. WordPress is now the most popular CMS in use, with more than 60% market share.2 Figure 1-1 shows a slide from Matt Mullenweg’s “State of WordPress” presentation from WordCamp San Francisco 2013. The upside-down pyramid on the left represents a circa 2006 WordPress, with most of the code devoted to the blog application and a little bit of CMS and platform code holding it up. The pyramid on the right represents the current state of the WordPress platform, where most of the code is in the platform itself, with a CMS layer on top of that, and the blog application running on top of the CMS layer. WordPress is a much more stable platform than it was just a few years ago.

Figure 1-1. Diagrams from Matt Mullenweg’s 2013 “State of WordPress” presentation. WordPress wasn’t always so stable.

You can use the Custom Post Types API to tweak your WordPress installation to support other content types besides blog posts or pages. We cover this in detail in Chapter 5.

WordPress is just for content sites

Similar to the “just for blogs” folks, some will say that WordPress is just for content sites.

First, even if WordPress were applicable for only content-based sites and apps, that would account for a large number of apps. The home screen of your phone probably includes a large number of content-based apps like Netflix, Twitter, Facebook, Reddit, and Evernote. These are very popular apps maintained by giant companies. Now, we’re not suggesting these apps should run on WordPress, but we are suggesting that you could build an app similar to these on using WordPress as an application framework.

Second, as we’ll go over in detail in this book, WordPress is a great framework for building more interactive web applications as well. The main feature allowing WordPress to be used as a framework is the Plugin API, which allows you to hook into how WordPress works by default and change things. Not only can you use the thousands of plugins available in the WordPress repository and elsewhere on the internet, you can also use the Plugin API to write your own custom plugins to make WordPress do anything possible in PHP/MySQL.

WordPress doesn’t scale

Some will point to a default WordPress installation running on low-end hosting and note how the site slows down or crashes under heavy load, and thus conclude that WordPress doesn’t scale.

Or maybe when we suggested you could build a site like Facebook using WordPress, you rightly scoffed at the idea.

Note

If you are intending to build an app at Facebook scale, this is not the book for you. Ask your CTO what part of their billion-dollar budget is allocated to your app and which engineers you need to headhunt from Google and Amazon to build your custom solution.

In reality, many high-traffic sites run on WordPress. WordPress.com runs on the same basic software as any WordPress site and is one of the most highly trafficked websites in the world.

As use of your app scales up, you will need to upgrade and swap out individual components to meet that scale. The issues with scaling WordPress are the same issues you have scaling any application: caching pages and data, handling database calls more rapidly, and improving network performance. Large sites like WordPress.com, TechCrunch, and the New York Times blogs have scaled on WordPress. Similarly, most of the lessons learned scaling PHP/MySQL applications in general apply to WordPress as well. We cover scaling WordPress apps in detail in Chapter 14.

WordPress is insecure

Like any open source product, there will be a trade-off with regard to security when using WordPress.

On the one hand, because WordPress is so popular, it will be the target of hackers looking for security exploits. And because the code is open source, these exploits will be easier to discover.

On the other hand, because WordPress is open source, you will hear about it when these exploits become public, and someone else will probably fix the exploit for you.

We feel more secure knowing that there are lots of people out there trying to exploit WordPress and just as many people working to make WordPress secure against those exploits. We don’t believe in “security through obscurity” except as an additional measure. We’d rather have the security holes in our software come out in the open rather than go undetected until the worst possible moment.

Chapter 8 covers security issues in more detail, including a list of best practices to harden your WordPress install and how to code in a secure manner.

WordPress plugins are crap

The Plugin API in WordPress and the thousands of plugins that have been developed using it are the secret sauce and, in our opinion, the number-one reason that WordPress has become so popular and is so successful as a website platform.

Some people will say, “Sure, there are thousands of plugins, but they are all crap.” OK, some of the plugins out there are crap.

But there are a lot of plugins that are most definitely not crap—among them, AppPresser, developed by coauthor Brian Messenlehner. If you like using WordPress to manage your written content or ecommerce store, the AppPresser plugin and platform is the fastest way to get that content or store into a mobile app.

Paid Memberships Pro, developed by coauthor Jason Coleman, is also not crap. Using Paid Memberships Pro to handle your member billing and management will allow you to focus your development efforts on your app’s core competency instead of how to integrate your site with a payment gateway.

A lot of plugins do something very simple (e.g., hiding the admin bar from nonadmins), work exactly as advertised, and don’t really have room for being crap.

Themes and plugins found in the WordPress.org repository are heavily vetted by volunteers for security and code quality. The WordPress.org Theme Review process is notoriously stricter and more comprehensive than processes at other marketplaces. The Tide project is working to add automated tests to the plugin and theme repositories that will result in higher-quality plugins and updates while also detecting compatibility and security issues faster.

Even the crappy plugins can be fixed, rewritten, or borrowed from to work better. You may find it easier sometimes to rewrite a bad plugin instead of fixing it. However, you are still further ahead than you would be if you had to write everything yourself from scratch.

No one is forcing you to use WordPress plugins without vetting them yourself. If you are building a serious web app, you’re going to check out the plugin code yourself, fix it up to meet your standards, and move on with development.

When Not to Use WordPress

WordPress isn’t the solution for every application. This section describes a few cases in which you wouldn’t want to use WordPress to build your application.

You Plan to License or Sell Your Site’s Technology

WordPress uses the GNU General Public License, version 2 (GPLv2), which has restrictions on how you distribute software that you build with it. Namely, you cannot restrict what people do with your software once you sell or distribute it.

This is a complicated topic, but the basic idea is if you are only selling or giving away access to your application, you won’t need to worry about the GPLv2. However, if you are selling or distributing the underlying source code of your application, the GPLv2 will apply to the code you distribute.

For example, if we host SchoolPress on our own servers and sell accounts to access the app, that doesn’t count as distribution, and the GPLv2 doesn’t impact our business at all.

However, if we wanted to allow schools to install the software to run on their own servers, we would need to share the source code with them. This would count as an act of distribution. Our customers would be able to legally give away our source code for free even if we had initially charged them for the software. We must use the GPLv2 license, which doesn’t allow us to restrict what users do with the code after they download it.

Another Platform Will Get You “There” Faster

If you have a team of experienced Ruby developers, you should use Ruby to build your web app. If there is a platform, framework, or bundle that includes 80% of the features you need for your web app and WordPress doesn’t have anything similar, you should probably use that other platform.

Flexibility Is Not Important to You

One of the greatest features of a WordPress site is the ability to quickly change parts of your website to better fit your needs. For example, if Facebook “likes” stop driving traffic, you can uninstall your Facebook Connect plugin and install one for Pinterest.

Generally, updating your theme or swapping plugins on a WordPress site will be faster than developing features from scratch on another platform. However, for cases in which optimization and performance are more important than being able to quickly update the application, programming a native app or programming in straight PHP is going to be the better choice.

If your app is going to do one simple thing, you will want to build your app at a lower level. For example, the Paid Memberships Pro license server is basically a single JSON file of add-on information and a small script to check license keys and deliver zipped files. Jason built that license server in straight PHP, with heavy amounts of caching. The license server runs on a $10/month DigitalOcean Sroplet and serves more than 80,000 sites running Paid Memberships Pro.

Similarly, if you have Facebook’s resources, you can afford to build everything by hand and use custom PHP-to-C compilers and native iOS components to shave a few milliseconds off your website and app load times.

Your App Needs to Be Highly Real Time

One potential downside of WordPress, which we will get into later, is its reliance on the typical web server architecture. In the typical WordPress setup, a user visits a URL, which communicates with a web server (like Apache) over HTTP, kicks off a PHP script to generate the page, and then returns the full page to the user.

There are ways to improve the performance of this architecture using caching techniques and/or optimized server setups. You can make WordPress asynchronous by using Ajax calls or accessing the database with alternative clients. However, if your application needs to be real time and fully asynchronous (e.g., a chatroom-like app or a multiplayer game), you have our blessing to think twice about using WordPress.

Many WordPress developers, including Matt Mullenweg, the founder and spiritual leader of WordPress, understand this limitation. More and more of the functionality of WordPress is being moved into JavaScript, where computation can be pushed off to the browser and frameworks like REACT can be used to create highly interactive experiences. The new Gutenberg editor added in WordPress 5.0 is the best example of this move and is indicative of things to come, but for now you’ll face an uphill battle trying to get WordPress to work asynchronously with the same performance as a native app, or something built entirely in Node.js or other technologies specifically suited to real-time applications.

WordPress as an Application Framework

Content management systems like WordPress, Drupal, and Joomla are often left out of the framework discussion, but in reality, WordPress (in particular) is really great for what frameworks are supposed to be about: quickly building applications.

Within minutes, you can set up WordPress and have a fully functional app with user signups, session management, content management, and a dashboard to monitor site activity.

The various APIs, common objects, and helper functions covered throughout this book allow you to code complex applications faster without having to worry about lower-level systems integration.

Figure 1-2 shows that righthand triangle from Mullenweg’s 2013 “State of WordPress” presentation depicting a stable WordPress platform with a CMS layer built on top and a blogging application built on top of the CMS layer.

The reality is that the majority of the current WordPress codebase supports the underlying application platform. Think of each WordPress release as an application framework bundled with a sample blogging app.

Figure 1-2. The WordPress platform

WordPress Versus Model-View-Controller Frameworks

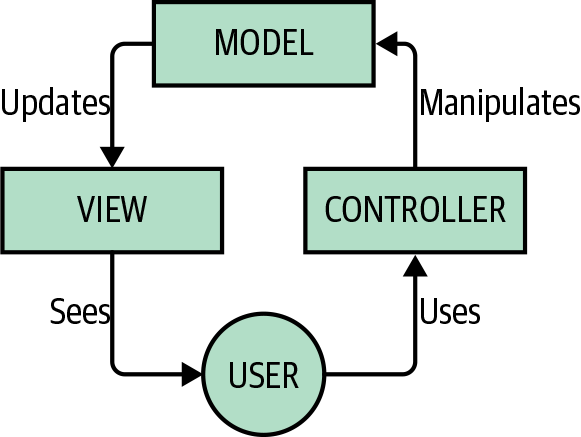

Model-view-controller (MVC) is a common design pattern used in many software development frameworks. The main benefits of using an MVC architecture are code reusability and separation of concerns (SoC). WordPress doesn’t use an MVC architecture, but does in its own way encourage code reuse and SoC.

Here, we’ll briefly explain the MVC architecture, and how it maps to a WordPress development process. If you’re familiar with MVC-based frameworks, this section should help you understand how to approach WordPress development in a similar way.

Figure 1-3 describes a typical MVC-based application. The end user uses a controller, which manipulates the application state and data via a model, which then updates a view that is shown to the user. For example, in a blog application, a user might be looking at the recent posts page (a view). The user would click a post title, which would take the user to a new URL (a controller) that would load the post data (in a model) and display the single post (a different view).

Figure 1-3. How MVC works

The MVC architecture supports code reusability by allowing the models, views, and controllers to interact. For example, both the recent posts view and the single posts view might use the same post model when displaying post data. The same models might be used in the frontend to display posts and in the backend to edit them. The MVC architecture supports SoC by allowing designers to focus their attention on the views while programmers focus their attention on the models.

You could try to use an MVC architecture within WordPress. There are a number of projects to help you do just that; however, we think trying to strap MVC onto WordPress could lead to issues unless the WordPress core were to officially support MVC. Instead, we suggest following the “WordPress Way,” as outlined in this book.

Still, if you are interested, the WP MVC plugin is in active development and helps you to use an MVC framework to create WordPress plugins. If you don’t want or need to go full MVC, there are a couple of ways to map an MVC process to WordPress.

Models = plugins

In an MVC framework, the code that stores the underlying data structures and business logic is found in the models. This is where the programmers will spend the majority of their time.

In WordPress, plugins are the proper place to store new data structures, complex business logic, and custom post type definitions.

This comparison breaks down in a couple of ways. First, many plugins add view-like functionality and contain design elements—take any plugin that adds a widget to be used in your pages. Second, forms and other design components used in the WordPress dashboard are generally handled in plugins as well.

One way to make the SoC more clear when adding view-like components to your WordPress plugins is to create a templates or pages folder and put your frontend code into it. Common practice is to allow templates to override the template used by the plugin. For example, when using WordPress with the Paid Memberships Pro plugin, you can place a folder called paid-memberships-pro/pages into your active theme to override the default page templates. (This technique for overriding plugin templates is covered in Chapter 4.)

Views = themes

In an MVC framework, the code to display data to the user is written in the views. This is where designers and frontend developers will spend the majority of their time.

In WordPress, themes are the proper place to store templating code and logic.

Again, the comparison here doesn’t map one to one, but “views = themes” is a good starting point.

Controllers = template loader

In an MVC framework, the code to process user input (in the form of URLs or $_GET or $_POST data), and decide which models and views to use to handle a request, is stored in the controllers. Controller code is generally handled by a programmer and often set up once and then forgotten. The meat of the programming in an MVC application happens in the models and views. Even so, controllers are an important part of how an app works.

In WordPress, all page requests (unless they are accessing a cached .html file) are processed through the index.php file and processed by WordPress according to the template hierarchy. The template loader figures out which file in the template should be used to display the page to the end user. For example, use search.php to show search results, single.php to show a single post, and so on.

The default behavior can be further customized via the WP_Rewrite API (covered in Chapter 7) and other hooks and filters. You can find information on the template hierarchy in the WordPress Theme Handbook; we cover the template hierarchy in more depth in Chapter 4.

For a better understanding of how MVC frameworks work, the PHP framework Yii has a great resource explaining in detail how to best use its MVC architecture.3

For more on how to develop web applications using WordPress as a framework, continue reading this book.

Anatomy of a WordPress App

In this section, we describe the app we built as a companion for this book: SchoolPress. We’ll cover the intended functionality of SchoolPress, how it works and who will use it, and—most important for this book—how each piece of the app is built in WordPress.

Don’t be alarmed if you don’t understand some of the following terminology. In later chapters, we review everything introduced here in more detail. Whenever possible, we point to the chapter that corresponds to the feature discussed.

Note

This book is not meant to be a “how to re-create the SchoolPress app” book or step-by-step walkthrough guide. When it makes sense, we use SchoolPress in our code examples throughout the book so you don’t have to spend time understanding the context of every individual example.

What Is SchoolPress?

SchoolPress is a web app that makes it easy for teachers to interact with their students outside of the classroom. Teachers can create classes and invite their students to them. Each class has a forum for ad hoc discussion and also a more structured system for teachers to post assignments and have students turn in their work.

You can find the working app on the SchoolPress website. The application’s source code can be found in the SchoolPress GitHub repo.

SchoolPress Runs on a WordPress Multisite Network

SchoolPress runs a multisite version of WordPress. The main site hosts free accounts where teachers can sign up and start managing their classes. It also has all of the marketing information for separate school sites on the network, including the page to sign up and check out for a paid membership level.

Schools can create a unique subdomain that will house classes for their teachers. This setup offers finer control and reporting for all classes across the entire school. Details on using a multisite network with WordPress can be found in Chapter 12.

The SchoolPress Business Model

SchoolPress uses the Paid Memberships Pro, PMPro Register Helper, and PMPro Network plugins to customize the registration process and accept credit card payments for schools signing up.

Schools can purchase a unique subdomain for their school for an annual fee. No other SchoolPress users pay for access. When school administrators sign up, they can specify a school name and slug for their subdomain <ourschool>.schoolpress.me. A new network site is set up for them and they are given access to a streamlined version of the WordPress dashboard for their site.

The school admin then invites teachers into the system. Teachers can also request an invitation to a school that must be approved by the school admin. Teachers can invite students to the classes they create. Students can also request an invitation to a class that must be approved by the teacher.

Teachers can also sign up free of charge to host their classes at schoolpress.me. Pages hosted on this subdomain may run ads or other monetization schemes. Details on how to set up ecommerce with WordPress are discussed in Chapter 15.

Membership Levels and User Roles

Teachers are given a Teacher membership level (through Paid Memberships Pro) and a custom role called “Teacher” that gives them access to create and edit their classes, moderate discussions in their class forums, and create and manage assignments for their classes.

Teachers do not have access to the WordPress dashboard. They create and manage their classes and assignments through frontend forms created for this purpose.

Students are given a “Student” membership level and the default “Subscriber” role in WordPress. Students have access to view and participate only in classes to which they are invited by their teachers. Details on user roles and capabilities are explained in Chapter 6, and Chapter 15 covers using membership levels to control access.

Classes Are BuddyPress Groups

When teachers create “classes,” they are really creating BuddyPress groups and inviting their students to the group. Using BuddyPress, we get class forums, private messaging, and a nice way to organize our users.

The class discussion forums are powered by the bbPress plugin. A new forum is generated for each class, and BuddyPress manages access to the forums. Details on leveraging third-party plugins like BuddyPress and bbPress can be found in Chapter 3.

Assignments Are a CPT

Assignments are a CPT that uses a frontend submission form for teachers to post new assignments. Assignments are just like the default blog posts in WordPress, with a title, body content, and attached files. The teacher posting the assignment is the post’s author.

Note

WordPress has built-in post types like posts and pages and built-in taxonomies like categories and tags. For SchoolPress, we are creating our own CPTs and taxonomies. Find more on creating custom post types and taxonomies in Chapter 5.

Submissions Are a (Sub)CPT for Assignments

Students can post comments on an assignment, and they can also choose to post their official submission for the assignment through another form on the frontend.

Submissions, like assignments, are also CPTs. Submissions are linked to assignments by setting the submission’s post_parent field to the ID of the assignment to which it was submitted. Students can post text content and also add one or more attachments to a submission.

Semesters Are a Taxonomy on the Class CPT

A custom taxonomy called Semester is set up for the group/class CPT. School admins can add new semesters to their sites. For example, a “fall 2019” semester could be created and teachers could assign this semester when creating their classes. Students then can easily browse a list of all fall 2019 classes.

Departments Are a Taxonomy on the Class CPT

A custom taxonomy called Department is also set up for the group/class CPT. This is also available as a drop-down list for teachers when creating their classes, and allows students to browse the list of classes by department.

SchoolPress Has One Main Custom Plugin

Behind the scenes, the custom bits of the SchoolPress app are controlled from a single custom plugin called SchoolPress. This—the main plugin—includes definitions for the various CPTs, taxonomies, and user roles. It also contains the code to tweak the third-party plugins SchoolPress uses like Paid Memberships Pro and BuddyPress.

The main plugin also contains classes for school admins, teachers, and students that extend the WP_User class and classes for classes, assignments, and submissions that wrap the WP_Post class. These (PHP) classes allow us to organize our code in an object-oriented way that makes it easier to control how our various customizations work together and to extend our code in the future. These classes are fun to work with and allow for the code shown in Example 1-1.

Example 1-1. Possible user login events

if($class->isTeacher($current_user)){//this is the teacher, show them teacher stuff//...}elseif($class->isStudent($current_user)){//this is a student in the class, show them student stuff//...}elseif(is_user_logged_in()){//not logged in, send them to the login form with a redirect back herewp_redirect(wp_login_url(get_permalink($class->ID)));exit;}else{//not a member of this class, redirect them to the invite pagewp_redirect($class->invite_url);exit;}

Creating custom plugins is covered in Chapter 3, and extending the WP_User class in Chapter 6.

SchoolPress Uses a Few Other Custom Plugins

Occasionally, a bit of code will be developed for a particular app that would also be useful on other projects. If the code can be contained enough that it can run outside of the context of the current app and main plugin, it can be built into a separate custom plugin.

An example of this would be the Force First and Last Name as Display Name plugin that was a requirement for this project. It didn’t require any of the main plugin code to run and is useful for other WordPress sites outside of the context of the SchoolPress app. We created a separate plugin for this functionality and maintain it in the WordPress.org repository so others can use it and benefit from it.

SchoolPress Uses the Memberlite Theme

The main schoolpress.me site runs on a customized Memberlite child theme. If a school admin signs up for a premium subdomain, they can choose from a variety of Memberlite child themes; they can also change any of the theme’s colors, fonts, and logos to better fit school/class branding. Also, all themes use a responsive design that ensures the site will look good on mobile and tablet displays as well as desktop displays.

The code in the Memberlite theme is very strictly limited to display-related programming. The theme code obviously includes the HTML and CSS for the site’s layout, but also contains some simple logic that integrates with the main SchoolPress plugin (like the preceding branching code). However, any piece of code that manipulates the custom post types or user roles or involves a lot of calculation is delegated to the SchoolPress plugin.

Now that we’ve established what an app is, discussed why you might want to build one with WordPress, presented the “WordPress” way of separating concerns, and described at a high level our SchoolPress example app, let’s dig into the core of WordPress, what’s included, and how it works.

1 Many of the ideas in this section are influenced by the following blog posts: “What is a Web Application?” by Dominique Hazaël-Massieux, and “What is a Web Application?” by Bob Baxley.

2 W3Tech has regular surveys on the use of different content management systems.

3 Yii is an MVC-based PHP framework. Other PHP frameworks, like Laravel, are more popular among WordPress developers and the PHP community in general, but the MVC-related documentation on the Yii website is particularly well written.