I would never apply the word commodity to human beings. I would say that they are becoming some kind of economic unit that represents a cost and, to the receiving facility or region, represents an economic benefit.

JAMES R. ROBERTS, VICE PRESIDENT OF DOMINION1

THE EMERGENCE OF private prisons in the late twentieth century does not mark the first time private industry has profited from U.S. prisoners. Indeed, whether through slavery or incarceration, the United States has a long history of using captive labor for economic purposes, separate and apart from the moral or ethical questions that these practices present. Incarcerated people, much like slaves, were first and foremost a cheap and disenfranchised form of labor.

Early Prison Profiteers

Before the Revolutionary War, the British government sent thousands of convicted individuals to the Colonies to serve their prison sentences. The practice of “transportation” was deemed beneficial to Britain because it provided a way to remove the criminal element from society. The British government also avoided paying to house and feed these individuals in their jails by paying British merchant shippers the cost of the journey to transport these individuals to the Colonies. Those lucky enough to survive the long journey at sea, which was filled with outbreaks of typhoid and cholera, would become indentured servants. Once the boats arrived, merchants made money by auctioning off the convicted individuals, mostly to plantation owners, who bought the prisoners for their labor. After the war, as the number of slaves grew, especially in southern states, the practice of transporting convicted individuals was replaced with the slave trade.

One early example of how private prisons emerged comes from Kentucky, where prison privatization first took hold in 1825.2 The state leased the eighty-five-inmate Kentucky State Penitentiary at Frankfurt to Joel Scott, a businessman and textile manufacturer who pledged to return half of the net prison labor profits to the state.3 The contract authorized Scott to employ the inmates in “hard labor” and gave him the power to “inflict such punishment, either by solitary confinement or otherwise, as may be reasonable and best calculated” to meet the employment and manufacturing objectives described.4 The incarcerated men constructed chairs, shoes, wagons, sleighs, and engaged in weaving. Two-thirds of the inmates were engaged making rope from hemp. This privatized leasing model continued in Kentucky for fifty-five years.5

Many trace the origins of privatization in corrections to the emergence of the ‘convict lease system’, which became prevalent after the Civil War during Reconstruction. The Thirteenth Amendment—most famous for abolishing slavery—simultaneously abolished “involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” After slaves were released from their owners’ captivity, they were frequently labeled “trespassers,” “vagrants,” and “loiterers” on their former owners’ plantations.6 In 1876, the Mississippi legislature passed the “Pig Law,” which redefined grand larceny as “the theft of a farm animal or any property valued at ten dollars or more.” Violation of Mississippi’s Pig Law resulted in up to five years in prison.7 Once incarcerated for these petty crimes, former slaves found themselves leased to private companies and forced to rebuild after the destruction of the Civil War. The convict lease system emerged as a new form of slavery, with the Thirteenth Amendment’s “conviction” exception functionally imposing a de facto form of slavery that it ostensibly legally abolished.

Convict leasing attempted to solve the labor shortage facing the southern economy and provided southern states with revenue after the Civil War. In practice, a private company would pay a fee to the government for the lease of its convicts, and the private vendor would house, feed, and even discipline the convicted individuals. The convict lease system put these inmates—almost all of whom were former slaves—to work mining coal, logging, creating turpentine, laying railroad track, and working farms and plantations.8 Leasing out convicts allowed industries to pay significantly lower wages than would be paid to workers who were not imprisoned. In 1868, Georgia issued a convict lease for prisoners to businessman William Fort for work on the Georgia and Alabama Railroad. The contract specified “one hundred able bodied and healthy Negro convicts” in return for a fee to the state of $2,500.9

These inmates, almost all black, worked long hours in unsafe conditions and often were treated worse than they had been as slaves. One account notes that those who died as part of these construction projects had their bodies tossed into the excavations where they became part of the levees they were building.10 In South Carolina, for example, the death rate of inmates leased to the railroad industry was 45 percent in the late 1870s.11 Although record keeping was not very meticulous, between 1885 and 1920 “ten thousand to twenty thousand debtors, convicts, and prisoners toiled under these circumstances on an average day, the great majority of them African-American.”12

The convict lease system ended at the close of the nineteenth century, mostly due to the deteriorating economic conditions sweeping the nation. In Tennessee, for example, the economic depression of the 1890s depleted the profitability of the mining industry, which had taken advantage of most of the inmate labor.13 Around this time, a handful of states delegated the management of their prisons to wealthy entrepreneurs. By 1885, thirteen states contracted out their incarcerated populations to private contractors.14

In Louisiana, Samuel James, a Confederate major, was awarded a lease in 1869 to run the Louisiana State Penitentiary.15 Eleven years later, Major James bought Angola, an 8,000-acre plantation where he kept prisoners who were otherwise occupied building levees on the Mississippi River. His son took over the lease after James died in 1894, but media accounts of inhumane conditions inflicted on the prisoners forced the state of Louisiana to retake control of the state penitentiary system in 1901.

California’s San Quentin Prison also traces its roots to private management. Famous today for housing the largest death row in the country, San Quentin was one of the country’s first private prisons. In 1851, California leased San Quentin for ten years to two private entrepreneurs, James E. Estell and Mariano Guadalupe. Although there were only thirty-five state prisoners when the two businessmen signed the contract, a decade later the state prison population had grown to more than 600 inmates.16 According to accounts from the time, inmates slept on a ship offshore at night and built the prison by day, completing it in 1854.17 The prison eventually became notorious for its political corruption and budget woes. The guards mingled and drank with the men incarcerated at the prison, escapes were frequent, and it was rumored that the owners sold pardons for $200.18 Estell allegedly forced prisoners to make bricks and even refused to construct a wall to keep the inmates inside the prison grounds, forcing the state of California to build a wall at the prison. Before the state reluctantly erected the wall, almost fifty inmates escaped every year.19

In 1857, Governor John B. Weller, who disliked Estell and coincidentally happened to be running for the U.S. Senate, took the political opportunity to seize control of the prison in the presence of reporters. Although effective for publicity, the move was eventually ruled illegal by the Supreme Court of California because the lease was still active. San Quentin was returned to Estell, but he soon died and John F. McCauley and Lloyd Tevis became the owners of the prison contract.

McCauley, like his predecessors, turned a blind eye to conditions at San Quentin and was known to ignore prison inspectors and keep “prisoners barefoot and half-clothed.”20 None too pleased by this treatment of state prisoners, the California legislature voided the lease with McCauley, and Governor Weller took back the prison in the spring of 1858. McCauley sued the state and the governor for restitution of the seized property and prevailed in court. The judge ordered the state to return the prison to McCauley with an additional $12,229 plus court costs. On April 14, 1860, McCauley sailed to San Quentin on a chartered boat with a brass band.21 After a short-lived return, McCauley accepted the state’s offer of $275,000 and returned the operation of the prison to the state of California. The state has owned and operated San Quentin ever since.

Foreshadowing the 2016 sudden curtailment by the Department of Justice of relying on private prisons, in 1887 Congress passed a law forbidding contracting for any inmates in the federal prison system. A domino effect ensued; New York banned private prison contractors in 1897, with Massachusetts and Pennsylvania quickly passing their own legislation to eliminate private prisons in their states. Newspaper accounts of appalling conditions, malnourishment, whippings, and overcrowding ultimately motivated states to terminate leases on privately run state prisons in the early 1900s.

This history provides some context for examining modern privatization in corrections. In fact, the privatization of inmates in the United States is inexorably intertwined with how jails and prisons emerged and were formed. Although important lessons can be learned from America’s early dabbling in private corrections, today’s mega corporations operate within a set of norms, rules, and regulations that simply did not exist in the nineteenth century. As UCLA law professor Sharon Dolovich has written: “Today, there is also a stricter standard of political accountability, an extensive public bureaucracy with the capacity to regulate and administer complex institutions, and the default expectation that the state bears the burden of financing the prison system.”22

Despite modern regulations and laws restricting how private corporations operate in corrections, the legacy of slavery morphing into convict leasing casts a pall on modern-day incarceration. African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at a rate six times that of whites, and in five states (Iowa, Minnesota, New Jersey, Vermont, and Wisconsin) the ratio is more than ten to one.23 The nation’s policies created these disparities, but the legacy of profiting off of human suffering still haunts the privatization of corrections today.

Much of the first half of the twentieth century was marked by legislation limiting the privatization of corrections. Between 1929 and 1940, Congress enacted three separate laws aimed at protecting workers who faced stiff competition from the low-wage prison labor supply during the Great Depression. The Hawes-Cooper Act was enacted in 1929 and required that goods produced by out-of-state prison labor be subject to the laws of the importing state.24 As a result, states with laws on the books prohibiting in-state prison goods could restrict the sale of goods produced by out-of-state prisoners. Six years later, in 1935, Congress passed the Ashurst-Sumners Act, strengthening the Hawes-Cooper Act by making it a federal offense to ship prisoner-made goods to a state in which state law prohibited the receipt, possession, sale, or use of such goods.25 In 1940, Congress went one step further and enacted the Sumners-Ashurst Act, which made it a federal crime to knowingly transport prisoner-made items in interstate commerce for private use, regardless of existing laws in the states.26 Since then, goods made by inmates, such as license plates and soap, have been sold to other state agencies and not exported to other states. As unemployment decreased across the nation in 1978, Congress repealed the Hawes-Cooper Act.27 The next year Congress passed the Justice System Improvement Act, which lifted the Sumners-Ashurst Act’s ban on interstate trade of prison labor products and paved the way once again for inmate labor.

Although the next wave of privatization of adult correctional facilities did not emerge until the 1980s, private companies have owned and operated juvenile correctional facilities since the early 1900s. In the early 1970s, it was a common practice for nonprofits and private companies to run juvenile institutions. The Weaversville Intensive Treatment Unit for Juvenile Delinquents was one of the first privately owned high-security institutions operated under contract to the state by RCA Services.28 In 1982, Florida contracted out the operation of the Okeechobee School for Boys to the Eckerd Foundation, a nonprofit organization endowed with $100 million from Jack Eckerd’s fortune from his drugs store chain. In 1983, nearly two-thirds of the 3,000 juvenile detention and correctional institutions in the United States were privately operated.29

Overcrowded Facilities and the Birth of Modern Private Prison Firms

Today, almost weekly, media stories focus on overcrowded conditions in jails and prisons. In 2016, Alabama made headlines with news that it packed more than 24,000 inmates into a system designed to house about half that number. In California, one state prison squished 650 inmates into a makeshift dormitory inside the prison gymnasium, placing bunk beds side by side with almost no room to walk. A few years ago some California prisons were so crowded that inmates slept in triple bunk beds lining the walls of prison gymnasiums. In one of these so-called dormitories, an inmate was beaten to death, and correction officers neglected to notice the incident for several hours. In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court forced California to reduce its prison population because its facilities were so overcrowded and unhygienic that they constituted “cruel and unusual punishment.”30

Prison overcrowding first became apparent four decades ago. Between 1972 and 1985 the nation’s prison population more than doubled to 440,000 inmates, which played a major role in prison riots across the nation. The most notorious was the 1971 Attica uprising, in which inmates took control of a maximum security prison near Buffalo, New York, seizing hostages and issuing demands in front of a national television audience. The five-day riot resulted in the deaths of twenty-nine prisoners and ten hostages, and an additional 118 people had been shot. The 1972 New York Special Commission on Attica called the incident ‘‘the bloodiest encounter between Americans since the Civil War.’’ In Texas, the state prison system was filled to 200 percent capacity, and inmates slept on hallway floors and outside in tents. One Texas prison had to serve meals constantly from 2:00 AM to 11:00 PM to ensure that everyone was fed.31 In the mid-1970s, inmates in states across the country filed litigation challenging conditions of confinement.

Some legal relief occurred in 1980 when a federal judge in Texas ruled in Ruiz v. Estelle that the state prison system violated the Eighth Amendment’s protection against cruel and unusual punishment. The federal court found that conditions in the Texas Department of Corrections were deplorable, noting that inmates were “crowded two or three to a cell or in closely packed dormitories, inmates sleep with the knowledge that they may be molested or assaulted by their fellows at any time. Their incremental exposure to disease and infection from other inmates in such narrow confinement cannot be avoided. They must urinate and defecate, unscreened, in the presence of others. Inmates in cells must live and sleep inches away from toilets; many in dormitories face the same situation.”32 The Texas prison system was immediately placed under court supervision, and this tipped the first domino.

Prisoners across the nation began to win their lawsuits, and by 1985 prisons in two-thirds of the states were under court order to improve conditions that violated the Constitution.33 Caps on how many inmates could be housed in prisons were set, and some states released prisoners early to relieve overcrowding. Three years later the prison systems in thirty-nine states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands were under federal court orders to remedy conditions of confinement that violated constitutional standards.34 In 1983, 500 Michigan prisoners joined approximately 14,000 other formerly incarcerated individuals nationwide whose sentences had been shortened since 1980 because of prisons bursting at their seams.35 Even the federal prison population operated between 27 percent and 59 percent over capacity.36

Not all prisoners could be released early, so the larger effect of overcrowding was a demand for more cells and new prisons. The nation’s willingness to build itself out of overcrowding is perhaps the pivotal moment in the history of private prisons. Policy makers could have invested in treatment and diversion programs, reversing the tide of bodies triple- and quadruple-bunked in U.S. prisons. Instead they gorged on an unprecedented prison spending spree. Taxpayers invested in an expansion of metal and bars resulting in an unparalleled investment in corrections, from slightly under $7 billion in 1980 to $40 billion by 1995.

State after state faced a massive crisis to reduce its prison populations or build additional, expensive facilities, and policy makers had to choose. Taxpayers were soon unwilling to foot the bill to pay for more prisons, but legislators would lose reelection if they appeared to be soft on crime. Any “discussion of alternatives to incarceration was the kiss of death.”37

In 1982 the national unemployment rate topped 10 percent, and more Americans were unemployed than at any time since the Great Depression. Taxpayers voted down bond issue after bond issue to fund state prison expansion. Hypocritically, they continued to call for tougher sentencing laws and more imprisonment to improve public safety. This hypocrisy doubled the nation’s prison population between 1972 and 1984. In 1984 the Department of Justice stated that “prison administrators and staff continued to grapple with a shortage of available housing capacity to accommodate the 1983 population.”38

Modern Private Prisons Emerge

By the mid-1980s, a great many states faced significant budget shortfalls traceable to the increased costs associated with operating their growing prisons systems.39 While correctional agencies raced to comply with court orders to reduce overcrowding, a group of astute businessmen pored over inmate projection reports and analyzed a new growth industry—the privatization of prisons.

Privatization is a contract process that shifts public functions, responsibilities, and capital assets, in whole or in part, from the government to the private sector. Specific services can be contracted out, which requires a competitive bidding process, and most jails and prisons privatize a whole host of services: medical, mental health, educational programming, food services, maintenance, and administrative office security.40 Under this model, the correctional agency continues to run the facility and the day-to-day operations. In another form of privatization—the one most people think about—the government transfers complete ownership of assets and management duties to a corporation. In this model, a private company owns and operates the prison.

The privatization trend emerged as three realities coalesced: (1) the rising belief in the potential of the free market, (2) the skyrocketing number of prisoners, and (3) the price tag of mass incarceration.41 Consistent with President Reagan’s philosophy, this trend stemmed from the growing costs of imprisonment and a desire to reduce the size and scope of the government.

Leaseback Agreements

For a few years in the early 1980s, a 1981 change in the federal tax law encouraged private investment in correctional facilities. This was a precursor to the private corporations of today owning and operating jails and prisons: a “quasi-public body” had the legal authority to sell shares to investors to finance the building of prisons. State and local governments contracted with private companies to build facilities and lease them back to the government. At the time, government agencies saw this as a boon because they were not forced to raise taxpayer dollars to build jails and prisons. Instead, they could invest in businesses that would repay their investment plus interest over the life of the lease. In most cases, the contract provided that the government agency would own the facility at the end of the lease term. In addition, the bonds were tax exempt for investors, and policy makers could sidestep the onerous process of gaining voter approval and authorization for capital expenditures.

E. F. Hutton traced the leaseback structure to a plan they developed for Jefferson County, Colorado, which was under federal court order to relieve overcrowding of an outdated prison facility. Voters twice rejected a proposal to raise the sales tax to finance a new jail.42 The leaseback worked like this: a Los Angeles corporation supplied a little more than $30 million to build a jail for 382 inmates; the county leased the facility until 1992, at which time it was expected to have repaid the $30 million; the county paid investors 8.75 percent interest, and the county would own the facility by 1992.43

By 1985, E. F. Hutton had created a $300 million prison leaseback plan for the state of California in addition to a $65 million jail leaseback for the city of Philadelphia. That same year, Shearson Lehman Brothers announced that it brokered a $32 million prison leaseback for Kentucky, an $18 million jail for Los Angeles, and a $15 million jail for Portland, Oregon.44

Three major Wall Street players—E. F. Hutton, Merrill Lynch, and Shearson Lehman—had high hopes for the future of the leaseback agreements, but “despite some initial ballyhoo, they never swept the nation.”45 The waning interest among investors can be traced to another change to the 1986 federal tax code, which limited the availability of tax-exempt financing for private industry.46 Although not often mentioned in discussions of the history of correctional privatization, tax reforms paved the way for private corporations to profit from the national prison boom.

New York also toyed with tax credits for private prison construction in reaction to what was seen as an out-of-control drug problem in New York City in the 1960s and 1970s, and likely because of presidential aspirations of Governor Nelson D. Rockefeller. The governor signed legislation in 1973 enacting the harshest drug laws in the nation. The penalty for selling 2 ounces or more of heroin, morphine, opium, cocaine, or marijuana, or of possessing 4 ounces or more of the same substances, was a minimum fifteen-year sentence and a maximum of twenty-five years to life in prison, similar to a sentence for second-degree murder.

The prison population skyrocketed as drug offenders in New York’s correctional facilities surged from 11 percent in 1973 to a peak of 35 percent in 1994. Despite the political backing for tougher drug sentences, not all taxpayers agreed. In 1981, a statewide coalition of church and criminal justice groups organized to strike down Governor Carey’s proposed $475 million bond issue to expand state and local prisons.47 New York voters rejected the bond issue that November by a slim margin of 13,000 votes.48 To find a solution to New York’s conundrum, New York Senator Alfonse D’Amato sponsored the Prison Construction Privatization Act of 1984 to sway private industry to invest in prisons by permitting investment tax credits and accelerated depreciation for these investments.49 This solution played out in states across the country because the citizenry demanded public safety, less crime, and more people in jail but didn’t want to foot incarceration’s expensive bill.

Private Prison Corporations Unveiled

The 1980s saw a great deal of activity around innovative ways to lock up prisoners. A 1982 congressional proposal to build a federal prison for serious offenders in the Arctic failed.50 However, the decade also gave birth to the modern private prison, an experiment that has flourished.

The biggest players in the game in the early 1980s—and those poised to notice the tremendous financial potential of America’s penchant for metal bars—were the founders of Corrections Corporation of America (CCA). It was formed in 1983 by Thomas Beasley, formerly head of the Republican Party of Tennessee; Robert Crants, a businessman with connections to Sodexho-Marriot Services; and T. Don Hutto, who served as the president of the American Correctional Association and as the director of corrections in Virginia and Arkansas. Hutto was no stranger to the profit motive when it comes to corrections; in 1978 the U.S. Supreme Court found that Arkansas “evidently tried to operate their prisons at a profit” as inmates were ordered to work on prison farms ten hours a day, six days a week, without appropriate clothing and footwear.51

CCA was originally funded with $10 million raised primarily by a Nashville venture capital firm, Massey Burch Investment Group,52 the financiers of Kentucky Fried Chicken and the Hospital Corporation of America (HCA).53 The Massey Burch Group was headed by Jack Massey, a close friend of Governor Lamar Alexander. Born with political connections and venture capital backing, CCA had the right stuff to convince policy makers to entrust them with the care of America’s inmates.

Beasley told a reporter in 1983 that “CCA will be to jails and prisons that are owned and managed by local, state, and federal governments what Hospital Corporation of America has become to medical facilities nationwide.”54 Founded in the late 1960s, HCA acquired hundreds of nonprofit hospitals claiming that it could run them better and more efficiently. It has achieved some successes, such as “economies of scale and purchasing power,” but HCA’s record has also been spotty. Practices such as reducing staff and accusations of “cherry-picking” patients to “garner profitable admissions” have been criticized.55

The Department of Justice launched a ten-year investigation into the charging practices of HCA, looking into claims that it defrauded the government by exaggerating the seriousness of the illnesses they were treating when it billed Medicare and Medicaid programs.56 In late 2002, HCA settled the complaint and agreed to pay the U.S. government $631 million, plus interest. Although plagued by scandals—filing false cost reports, fraudulently billing Medicare for home health care workers, and paying kickbacks in the sale of home health agencies and to doctors to refer patients—the company remains profitable today.57 In March 2011, HCA sold 126.2 million shares for $30 each, raising about $3.79 billion, making it the largest private-equity-backed IPO in U.S. history.58

Beasley and the other cofounders of CCA held up HCA as a model for how the private sector could more efficiently run facilities. The challenge to CCA’s business model was that the corrections industry is an expensive proposition. Departments of corrections are responsible for the food, clothing, and housing of thousands of inmates, and the largest expense is labor. Prison guards are expensive, almost always unionized, and require benefits beyond salaries such as pensions, health insurance, education, and training.

For the government to turn a profit on any private venture, the contract price must be lower than what the state would pay to operate the facility itself. This puts private operators in a bit of a Catch-22. To save money, private corporations need to run their prisons at a lower cost but ensure that the facility complies with the contract and state and federal regulations. Because the bulk of prison costs stem from labor (65 to 70 percent of operational costs are for staff salaries, benefits, and overtime), private companies tend to rely on cheaper nonunion labor.59 Private correction officers are generally not members of a union, and in 2015 they earned salaries about $7,000 lower than that of the average public corrections officer.60

CCA entered the correctional scene in October 1984 when it signed a contract to manage the Silverdale Detention Center in Hamilton County, Tennessee. This marked the first time that government at any level in the United States contracted out the entire operation of a jail, and the county hoped for a substantial savings. The milestone was noteworthy for another reason; the county learned that it was on the hook to pay $200,000 more than budgeted. Some county officials spoke up that it was a mistake to hand over control of the institution to CCA because the county would have spent less money without the deal.61

CCA contracted to operate the jail for a per diem fee of $21 a prisoner, which was $3 less than the county paid to house the inmates. The deal seemed to make sense at the time, in part due to strict enforcement of the state’s driving while under the influence laws.62 But the inmate population soon exploded, and Hamilton County had not planned for this contingency. The county would have paid only an extra $5 a day to house the overflow prisoners, but CCA’s contract guaranteed a per diem payment of $24 per person when the jail reached a specific capacity. This was an enormous boon for CCA, which eventually double-bunked the inmates. The Hamilton County contract was a harbinger of things to come in thousands of jurisdictions across the country.

Because so many of the costs of maintaining and running correctional facilities are fixed, the total costs are not greatly affected by each additional prisoner. For example, approximately the same number of staff members (guards, kitchen staff, janitors, medical staff) are needed whether the facility is running at capacity or 25 percent below capacity. It costs the same amount to operate a facility at 60 or 70 percent capacity as it does to operate a facility that is full. Similar to the business model for hotels, once cleaning staff, front desk personnel, bellmen, and managers are paid, it is far more remunerative to keep the hotel at its highest occupancy rate. So when a private prison company is paid per inmate, it is almost always more financially profitable to operate at capacity. In Hamilton County, CCA earned massive profits by keeping the facility full.

In November 1984, Thomas Beasley appeared on 60 Minutes to promote CCA’s venture into private prisons. Before turning to Beasley, Morley Safer said, “Just a few years ago, the very idea of prison for profit would have seemed ludicrous, given the escalating costs and problems of running prisons, given that it’s an area of public service that only brings blame and rarely praise. Yet, here they are, companies like CCA.”63 After pointing out that prisons are a “growth industry,” Beasley told Safer, “the prison population in this country has never gone down but twice—during World War I and World War II—and those operations are self-explanatory, I think.”64

CCA Attempts to Take Over Entire Tennessee Prison System

Prison conditions worsened in the decade between 1975 and 1985. In 1985, Tennessee’s prisons were operating under court supervision for prison overcrowding, and a federal court ordered it to reduce the number of inmates because of overcrowding, unhygienic, and unsafe prison conditions. Tennessee’s prisons were under scrutiny for hundreds of assaults, dozens of killings and riots, and a slew of inmate escapes.65 U.S. District Judge Thomas Higgins ordered the state to refrain from adding additional inmates as long as the state prison system remained overcrowded.

By the summer of 1985, Tennessee inmates had reached their breaking point. Furious over new prison uniforms with horizontal stripes, inmates at four Tennessee prisons burned buildings and took guards hostage. The four prisons were the Turney Center in Only, the State Penitentiary in Nashville, the Morgan County Regional Correctional Facility at Wartburg, and the Southeastern Regional Correctional Facility in Bledsoe County. At the state prison in Nashville, inmates refused to release the guards until they had a chance to talk about their conditions during a televised news conference. On live television, one inmate stated, “The stripes, I think, were the main concern. Stripes don’t hold people, bars do.” The inmates also expressed frustration about bad food, overcrowded facilities, and a lack of programming.66

A group of criminal justice experts started working with the Tennessee Department of Corrections and legislators to safely reduce the state’s prison population. Peggy McGarry, from the Center for Effective Public Policy’s National Prison Overcrowding Project, was asked to advise them on how to effectively meet the judge’s mandate while ensuring safe communities. As McGarry sat outside Governor Lamar Alexander’s office in the fall of 1985, a retired Appeals Court judge who chaired the task force of state and local criminal justice experts who were studying the overcrowding issue came out of the governor’s office shaking his head. The judge said that he “had just heard the most amazing thing. Private prisons have offered to take over the entire state!” McGarry said that the “CCA went directly to the governor. They certainly did not work through the task force. We didn’t know about their offer until they told the governor.”67

To McGarry’s dismay, this news was more than mere rumor. CCA lobbyists were seen traversing the halls of the state capitol, and the offer soon splashed across newspapers.68 CCA had offered to take over Tennessee’s entire prison system for $250 million, along with a ninety-nine-year lease. Responding to the unconstitutional conditions of the state’s prisons, CCA President Thomas Beasley told reporters, “If I was the state, I couldn’t do it fast enough.”69

It is not surprising that CCA bypassed the task force and made their bold offer directly to Alexander. The governor had close (familial) ties to CCA. His wife, Honey Alexander, was an early investor in the company, as was Tennessee’s Speaker of the House, Ned Ray McWherter. Considering CCA’s offer, the governor told reporters, “We don’t need to be afraid in America of people who want to make a profit…. This state’s taxpayers would boot us clear into Kentucky if we turned our backs on a plan that would save us $250 million.”70

On the day CCA offered to take over Tennessee’s prison system, the fledgling for-profit corporation had already secured seven contracts to run correctional facilities: two to operate facilities for illegal immigrants in Houston and Laredo, Texas; a federal prerelease treatment center in Fayetteville, North Carolina; two juvenile facilities in Memphis, Tennessee; the Hamilton County Jail, in Chattanooga Tennessee; and a work camp in Panama City, Florida.71 A prescient description of CCA’s aggressive entrance into Tennessee corrections honed in on the core of what would become a debate over private prisons for the next four decades: “There was considerable disagreement as to whether Corrections Corp. of America’s lobbyists, roaming the Capitol halls last week, were cavalry coming to the rescue or profiteers coming to exploit.”72

Despite the severe pressure state officials faced from the federal courts to get their prisons under control by January 1, 1986, some in Tennessee’s government were less than smitten with this business proposition. One of those with grave concerns was state Attorney General W. J. Michael Cody, a President Jimmy Carter appointee in the Tennessee U.S. Attorneys’ office. Cody was concerned about hiring private guards for a “quasi-judicial function” and said, “they are going to impose punishments. They are going to advise parole boards. All of that is very different from private businesses providing government with transportation and food services.”73 In the end, Tennessee did not accept CCA’s proposition, but Governor Alexander proposed a compromise that still would benefit CCA. He recommended that private prison corporations build, own, and possibly even operate two new prisons with room for 500 inmates each. CCA had claimed that it could build the two new maximum security prisons in two years, twice as quickly as the state.

In another nod to the private prison industry, Tennessee passed the Private Prison Act of 1986, which paved the way for private prisons to operate in the state. The legislation granted the Tennessee Department of Corrections the authority “to contract with private concerns on a limited basis to afford an opportunity to determine if savings and efficiencies can be effected for the operation of correctional facilities.”74 CCA also received tremendous free publicity and national attention with the New York Times headline: “Company Offers to Run Tennessee Prisons.”75 Hutto stated that “it forced everyone to take us seriously. The offer ran on a full front page of the afternoon paper. We were a national story.”76

The private prison industry’s moment had arrived. By 1988, private correctional companies were running twenty-four correctional facilities and five detention centers under contract with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).77

Growth of the Private Prison Industry

Remarkably, with almost no track record measuring the effectiveness of their activity, CCA grew quickly. CCA’s first federal contract was awarded by INS, which authorized CCA to build and manage an immigration detention center in Houston. It opened in 1984. The first state contract was awarded to CCA in 1986 to operate a prison in Marion, Kentucky. In 1987, CCA signed contracts for the construction and management of a regional juvenile facility in east Tennessee and two minimum security, prerelease facilities in Texas. In acknowledgment of the profit opportunity the next few decades would bring, CCA’s 1994 Annual Report to shareholders stated, “there are powerful market forces driving our industry, and its potential has barely been touched.”

Although CCA was the biggest private prison firm, it was not the only game in town. The demands on state governments to address crowded prisons encouraged a slew of companies to join the nascent industry. Security services leader Wackenhut Corporation (now the GEO Group) and other companies bid on the management and operation of prisons across the nation. By 1984, Ted Nissen, founder of Behavioral Systems Southwest, held $5 million in contracts with California, Arizona, and the federal Bureau of Prisons to manage halfway houses, and held two contracts with INS to manage immigrant detention facilities.78 Two brothers, Charles and Joseph Fenton, founded Buckingham Security Ltd., which constructed a $20 million, 715-cell maximum security prison north of Pittsburgh in 1985. At the time, the brothers anticipated that they would house prisoners from several states.79

Private prisons began to gain a grip in the corrections field. Because government-run facilities failed to meet minimum constitutional requirements for a safe and humane environment, a market for private prisons emerged. Vendors began to move beyond their traditional role of running halfway houses and juvenile facilities and made proposal after proposal to build or operate jails and prisons.

Private Prisons Get Their First Congressional Hearings

The emergence of the for-profit prison industry in the early 1980s generated a great deal of interest from policy makers on Capitol Hill who had watched from afar. From November 1985 to March 1986, the House Judiciary Committee held its first ever congressional hearings on private prisons. Legislators hoped the hearings would provide insight into certain questions about this budding industry: whether privatization would save money, whether conditions of confinement would be improved in private prisons, and whether the government is even legally authorized to delegate this power to private companies. Ira Robbins, a law professor at the American University Law School, alluded to the feeling among many that “the government has been doing a dismal job in its administration of correctional institutions” and that prisoners are often “kept in conditions that shock the conscience, if not the stomach.”80

The subject matter was so novel that a staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)—an organization that advocates to eliminate private prisons today—testified that the “ACLU probably will not take a position with respect to the public policy aspects of privatization.”81 However, the ACLU warned that privatization “must be examined closely” before the government invests substantial resources into the private sector to run prisons and jails.

Some organizations expressed unease early on. The American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE) warned of impending doom. David Kelly, president of the Council of Prison Locals for the AFGE, said private prison “profit is directly linked to a constant and increasing supply of incarcerated prisoners. For the first time, it is in someone’s self-interest to foster and encourage incarceration.”82

The occasion provided CCA with its first opportunity to testify on Capitol Hill. Richard Crane, vice president of legal affairs for CCA, made the case for the government’s need to save money: “Yes, there are indeed con-artists in this world. But, if we are going to attribute that attitude to everyone then the government better get in the business of running everything from used car lots to taco stands.”83

So novel was the industry at the time that Kentucky Congressman Ron Mazzoli asked Crane, “What do your people wear? Do they wear uniforms?” Crane answered, “Uniforms.” To which Congressman Mazzoli asked, “The same uniform that would be standard, blue trousers and so on?” Crane responded, “No, brown is our color, light and dark brown.”84

Professor Robbins testified about the constitutionality of it all. “Government liability cannot be reduced or eliminated by delegating the governmental function to a private entity.”85 At the close of the November hearings, Judiciary Chair Kastenmeier thanked the witnesses for testifying: “It is something which in year 2000 we may look at in terms of failure or it may have disappeared from the scene or, indeed, it may have become something very significant in terms of this country.”86 The subcommittee met again to discuss this topic in March. The only two witnesses who testified were the director of the Bureau of Prisons and the president of the Council of Prison Locals, American Federation of Government Employees.

Excitement swirled around the idea of expanding the use of private prisons. Government officials and taxpayers alike clung to notions that private industry would raise the initial capital to build facilities more cheaply and efficiently than government. How? Corporations could circumvent years of government studies, bids, and approval by voters to issue government bonds to finance prison construction. Private prison corporations benefited from the political challenges state policy makers faced when fund-raising to build new prisons, and to build them fast enough to meet demand. As Crane testified during the congressional hearings: “We can do it less expensively. We know, for example, that our construction costs are about 80 percent of what the Government pays for construction.”87

CCA Emerges on Wall Street

The congressional hearings and CCA’s offer to take over Tennessee’s entire prison system gave CCA and the emerging private prison industry incredible publicity. Completing the trifecta, in October 1986 CCA went public on the stock exchange with 2 million shares and a total valuation of $18 million. In its prospectus CCA noted that “the corrections system, in whole or in part, of thirty-four states were under court order to improve conditions.”88 The prospectus also pointed out that “the privatization of the prisons and corrections industry offers federal, state and local governmental agencies an alternative in their efforts to comply with federal and state court orders on a cost-efficient basis.”89 The day after CCA emerged as a public company it was reported that the “average contract with the company provides for $31 a day per inmate and it costs CCA $6 a day per inmate, a profit of $25 a day per inmate.”90 In 1991, CCA’s revenues were barely over $50 million. A few years later, law professor and criminologist Norval Morris wrote that “it is unclear whether private prisons are the wave of the future of corrections…there is mixed evidence as to whether they are fulfilling their initial promise of less-expensive, more efficient service.”91

In 1994, Wackenhut Corrections Corporation’s initial stock offering was valued at almost $20 million. On the day of the offering, the corporation managed nearly 8,000 prison beds. By 1997, CCA’s revenues had increased nearly tenfold to $462 million, with a profit margin of over $50 million. At the same time, the number of prison beds CCA managed jumped from about 5,000 to more than 38,000, giving it a U.S. market share of over 50 percent.92

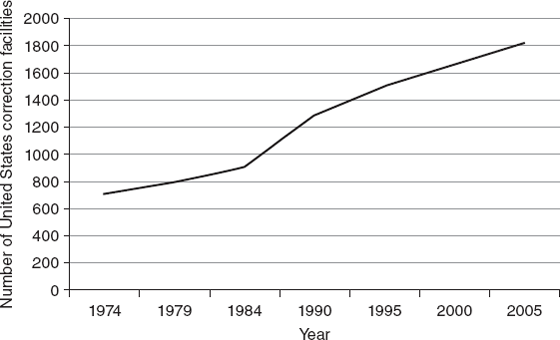

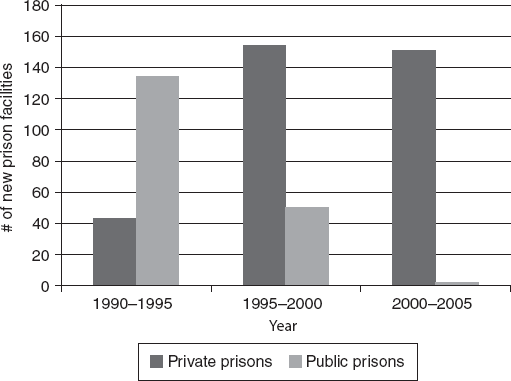

As figure 3.1 indicates, prison construction took off in the late 1980s and continued growing until the late 2000s. As figure 3.2 indicates, between 1995 and 2000, there were more than 150 new private prisons built across the country compared to about 50 public prisons. And, between 2000 and 2005, this trend continued with only two new public prisons constructed versus 151 private correction facilities, which drove almost all of the increase in the number of prisons built.93

Figure 3.1 Growth in Number of U.S. Correctional Facilities Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities,” Series 1974–2005.

Figure 3.2 Rate of Growth in Private and Public Prisons, 1995–2005 Source: Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Census of State and Federal Correctional Facilities,” Series 1974–2005.

If the private prison industry had a pivotal moment, it was in the mid-1980s. The nation, and the world, started to pay attention to the private industry as it wove its way into the fabric of the U.S. correctional system. No longer bearing the names of state departments of corrections and county jails, correction officers’ uniforms suddenly bore corporate logos. In 2011 it was reported that “over time, most states signed contracts, one of the largest transfers of state functions to private industry.”94

Many prison facilities were under emergency court orders to reduce the number of inmates they housed, so state and federal policy makers were reluctant to explore alternatives. Dealing with lagging budgets and barely making court ordered deadlines, most states turned their backs on conversations focusing on safely reducing incarceration, improving sentencing, and reducing recidivism.

It’s difficult to make the case that private industry created mass incarceration, but the very existence of private prisons let policy makers off the hook for recalibrating our nation’s system of punishment. The emergence of private prisons was a diversion from the real discussion about incarceration. They provided much-needed relief to inhumane and overstuffed prison cells, but these corporations promised to quickly build prison after prison, preventing a necessary examination of whether incarceration was the appropriate sanction for so many Americans who violated the criminal code.

Selman and Leighton pointed out that “the debate over private prisons included no discussion of alternatives to incarceration; nor did the congressional hearings or the commission’s final report include the word ‘rehabilitation.’ ”95 Where were the inspiring debates about the proper role of incarceration and punishment? Why were these conversations so rare? Policy makers missed a valuable opportunity to engage in an examination of whether too many people were in prison or whether there were more effective methods for addressing the underlying issues that caused their incarceration. In the next decades, corporations would seize the opportunity to make money off of almost every aspect of incarceration.