“It is true that man does not live by bread alone; he must eat something with it.”

Pellegrino Artusi

Italians are very impatient people. We can’t sit for more than a minute in traffic and we hate to wait for our food. That is why we invented antipasti, which literally means “before the meal [pasto].” When I first came to England, I thought it so strange to see people at parties and weddings standing around having drinks before they ate. Italians just want to get to the table as soon as possible, so the bread can arrive. Not just bread – we also want salami, prosciutto, maybe some marinated artichokes, some olives … We want to enjoy a glass of wine, to talk and argue, because everything we do in a day is a small drama and everyone has an opinion on it – but we need to eat while we are discussing it. Once the antipasti are on the table, that is the signal to relax, get into the mood and interact, because you have to pass the plates and everyone is saying, “Oh, what is this?” and “Can I have some of that?” It is all about conviviality and sharing and generosity.

A few miles from my home in Corgeno, in Lombardia, on the way to nowhere, is the village of Cuirone, with its pale, yellow-washed houses; a place that has hardly changed since I was a child. In the middle of the village is the Società Mutuo Soccorso, the cooperative shop and restaurant with a bakery attached, where they make fantastic chestnut and pumpkin bread, as well as the big pane bianco, which is the everyday bread. Inside the bakery, they have a basket full of drawstring bags, some gingham, some flowery. Each family makes its own bag, and the bakers know which bread they have, so in the morning when the loaves come out of the oven, the bags get filled up and delivered by scooter.

At one time in our region of Italy, most of the villages had a cooperativa, run by the locals, where everyone could bring their produce to sell and where you could get a simple lunch for not much money. Everything you ate would be produced locally. You have to remember that Italy has been a united country for not much more than a hundred years. Before that it was made up of different kingdoms, dukedoms, republics, and so on, each influenced by different neighbors and invading armies throughout its history.

Also in Italy you have a massive geographical change, from mountains to coastlines, from the colder north with its plains full of cows giving beef and milk for cheese, to the hot south, on the same parallel as Africa, where they grow a profusion of lemons, tomatoes, capers and peppers. So in every region, town and village, they have their own particular ingredients and style of cooking, which of course they will insist is absolutely the right way – and that what everyone else does is wrong.

In Corgeno, the cooperativa was next to my uncle’s restaurant, La Cinzianella, overlooking the lake, and when you turned twenty years old, you were asked to run it for the summer (the year my friends and I took charge we had a fantastic time). But now the space is rented out as a cafá and restaurant. In Cuirone, though, the cooperativa is still thriving, and sometimes, especially when I come home to visit, my mum and dad and my aunts, uncles and cousins all meet up there for lunch at the weekend. Lunch is at 12:30, and 12:30 is what they mean, so you don’t dare be late.

It’s a very simple place: a large room with a long bar down one side and wooden tables and chairs where the farmers and the old men of the village drink red wine and play cards. But the moment you sit down, big baskets of bread from the bakery arrive with bottles of local wine, and then the plates of antipasti: salami, prosciutto, lardo, carpaccio, local cheeses, artichokes, porcini. As one plate is taken away, more arrive, and so it goes on and on. Then, just when my wife, Plaxy, especially, is thinking that there can’t be any more food, out comes a pasta dish – maybe a baked lasagne – and then a fruit dessert.

The antipasti are based around simple produce, just like in people’s homes and most small restaurants. The members of the cooperativa bring whatever they have that is fresh that day, along with ingredients such as artichokes and mushrooms, prepared when they were in season, then preserved in big jars under vinegar or oil, or salamoia (brine). In Italy, things are done differently from in the UK, especially London, where you buy your food, eat it, and then buy some more. Most people in Italy still behave like they did in the old days, when you would always have a store cupboard full of dried or preserved foods because you never knew when there would be a war or some other disaster.

In smarter restaurants, the kitchen would have the chance to show off a little more with the antipasti. In my uncle’s kitchen at La Cinzianella we really worked at our antipasti, bringing out some fantastic flavors, because we knew that this prelude to the meal said a lot about what we were trying to achieve with our food, and about the dishes that would follow. The slicing machine was right in the middle of the big dining room, so everyone could see the cured meats being freshly cut, and we would prepare seafood salads and roasted vegetables. Imagine how I reacted the first time I went to a French restaurant and they sent out some canapás before the meal – those tiny, bite-sized things. I was shocked. I thought, If this is what the rest of the food is going to be like, forget it! Italians don’t like to fiddle about with fancy morsels, they just want to welcome people by sharing what they have, however simple, in abundance. An Italian’s role in life is to feed people. A lot. We can’t help it.

In Italy the concept of the “starter” – individually plated dishes that you eat by yourself, just you – is quite a modern thing. Only in the last twenty years or so have restaurants started putting them on the menu. Traditionally, after the antipasti the real “starter” was the pasta course, or first plate (i prini piatti). Then came the second plate (i secondi piatti), which would be meat or fish, and, to finish, fruit or a dessert (i dolci).

When I look at the books I have of old regional recipes, no mention is made of “starters” as we think of them today. One of the books I love most is La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene (Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well) by Pellegrino Artusi. All Italian cooks know about Artusi – he was a great gourmet and one of the first writers to gather together recipes from all over Italy. He published the book himself back in 1891, in the days when Italian food was considered a bit vulgar in “smart” society because the food of the royal courts was French.

Artusi spent twenty years traveling around Italy and his knowledge of regional produce and cooking was remarkable. His stories are full of beautiful descriptions and witty comments, sometimes using old Italian words that I have to look up. I keep his book in my office in the kitchen at Locanda to research ingredients and old recipes. But even Artusi has only a short section on “appetizers,” which is really just an acknowledgment of the moment before the meal when you show off your capacity to bring out food of a high quality. (Interestingly, he says that in Toscana they did things differently from other regions and served these “delicious trifles” after the pasta, not before.) Artusi talks about various cured meats, caviar and mosciame (salted and air-dried tuna), but the only “recipes” he gives for appetizers are a selection of crostini: fried bread topped with ingredients such as capers, chicken livers and sage, or woodcock and anchovies.

Traditionally, the kind of antipasti you ate was determined by where you lived. Around the coast there would obviously be more seafood, while inland there were cured meats. Every region would have different breads to serve with the antipasti: light, airy breads in the north, white unsalted bread in Toscana and enormous country loaves made with harder flour in the south – fantastic for bruschetta, which these days has become rather elevated in restaurants, but is really just chargrilled stale bread with a bit of garlic and tomato rubbed over it and some oil drizzled on top.

Even now, food in Italy is very regional, but after the Second World War, when everything became more abundant and people began to travel more, some chefs started to be a little inventive and borrow ideas for their antipasti from other regions, and from the street food you see cooked in cities such as Napoli by vendors with gas burners on trolleys: arancini (rice balls), crocchette (mashed potato croquettes), panzerotti (little pasties filled with meat, cheese, tomatoes or anchovies, then deep-fried), mozzarella in carrozza (mozzarella “in a carriage” – deep-fried between slices of bread), and frittelle (fritters filled with artichokes, mushrooms or prawns).

Nowadays in Italy – in the cities at least – like everywhere else in the world, the way people want to eat is changing, though perhaps a little more slowly than everywhere else. Not everyone wants a meal of several courses anymore. They want to be more relaxed, so you can order just a bowl of pasta and nobody thinks anything of it. And there are now city bars serving only antipasti, where you make yourself up a plate of whatever you want, and that’s all you have. Then there are the newer, smarter restaurants, which try really hard to make their starters more imaginative than a plate of carpaccio or an insalata caprese (tomatoes and mozzarella).

As for me, I am an Italian chef who has cooked in Paris and come of age in London, and inventive starters are what people expect from me. I might have in the kitchen a salami that is so beautiful it makes you cry, but I can’t just slice it and put it out with some artichokes and bread. I have to present it in a more sophisticated way. We must include such starters in the restaurant, but we can’t lose the pasta course, so the modern Italian menu usually has four sections: starters, pasta, main courses and dessert, which I know can seem daunting. Sometimes customers say, “What should I do? Do I have to have a starter, then pasta and a main course after that? Or can I have just pasta and a dessert?” Of course, you can do what you like; we just try to give a selection of everything an Italian would want to be offered, so you can eat as few or as many courses as you want.

However sophisticated our menu may be at Locanda, it always has its roots in classic regional Italian cooking. Sure, some of our favorite starters have come about, like all good dishes, from getting excited about a particular ingredient that comes into the kitchen, but many of them are simply our interpretation of the traditional elements of the antipasti misti – the artichokes, porcini and cured meats with which I and most of my kitchen staff have grown up. We look at them, rethink them and work at representing them in more imaginative or surprising ways.

The key is always to concentrate on just a few flavors. I think it is terrible to eat out in a restaurant and not remember afterward what you had because there were too many tastes happening at once on your plate. It is better to buy primary ingredients that have their own fantastic flavor and then you have to do less with them.

One of the great things that has happened since I came to this country is the revolution in the quality of ingredients. When the first Italian immigrants came to the UK and set up their restaurants, they brought what they could over from Italy and created a limited Italian kitchen, making Anglo-Italian dishes that catered to British tastes. Then when people began to be more interested in the genuine food of Italy, and were prepared to pay for real Parmigiano Reggiano and prosciutto di Parma and mozzarella di bufala, the best-quality food began to be imported, and producers in this country began to think, “We can do this, too,” So now there is a wonderful mix of high-quality Italian and British produce that you can use in your antipasti.

Very little of the traditional antipasti misti involves hot food – just a few deep-fried dishes, such as zucchini blossoms or squid, or the panzerotti and frittelle I mentioned earlier. Personally, I don’t like to eat too many fried foods at the start of a meal. So, instead, for our hot starters at the restaurant we look to the kind of main dishes that every Italian knows – great classics with brilliant flavors, such as sardines baked in bread crumbs, or pig’s feet – then we refine them and scale them down into starters. We play a bit of a game with the presentation, or make them easier for people to eat in a restaurant environment. Sometimes, when I see some of our famous customers thoroughly enjoying an appetizer of gnocchi fritti with culatello, it makes me smile to see something that you would find in any antipasti bar in Italy being celebrated in such a way, when I am only playing around with an idea that was worked out hundreds of years ago in Mantova. But perhaps that is the magic of a restaurant like Locanda – with a little imagination, the essential flavors and combinations of ingredients that have stayed in people’s hearts and minds for centuries can be elevated into something glamorous.

What we do in the restaurant and what we do at home, however, are two different things. At home, the idea is to keep things simple. But if you can approach cooking for family and friends with a little of the organization we need in a professional kitchen, you will enjoy a good meal as well, instead of being in the kitchen with smoke everywhere and your hair standing on end, so when someone comes in and says, “How are you?,” you want to scream. Use this chapter more as a source of inspiration than as a series of recipes. You don’t have to serve the dishes as individual starters, as we do in the restaurant. If you are having friends over, use the idea of shared antipasti to your advantage. Buy some good prosciutto, salami or mozzarella, which need nothing done to them, then choose a few of the recipes and dedicate your time to working on them, doubling the quantities if necessary, so you can serve everything on big plates to hand around. You can make your dessert in advance too, so you have only a main course to cook, which can be as simple as you like. It is my job to stay in the kitchen and cook for people. Your job is to make life as easy as possible, so when your friends arrive you can just put everything down on the table and sit and have a drink and talk with them.

At home in Corgeno I don’t remember my grandmother ever making a salad that was a dish in its own right, or had any sophistication, but salads have become an important part of the way we eat now. As with all our dishes in the restaurant, we look to classic Italian combinations of ingredients and flavors for our inspiration. What is exciting is to play with whatever is in season and what is good from the market: porcini mushrooms in autumn, root vegetables in winter, asparagus in spring, tomatoes in summer.

Like any other dish, a good salad needs structure – different textures, such as something soft, something with a little crunch. Throw in some pomegranate seeds and people think you have done something fantastic. Italians often find it difficult to put fruit in salad, but a chef who has been a real inspiration to me is David Thompson at Nahm, such a clever man – I really like what he does with Thai food. I came up with the idea of putting pomegranate into a winter salad after eating at Nahm, and having a brilliant salty-sweet warm salad, layered with leaves and peanuts and fruit such as mango and papaya – almost like a lasagne.

When we eat, we experience taste sensations in different parts of the mouth: sweet, sour, salty, bitter – and the most recently recognized, umami. Think about balancing ingredients that satisfy all these tastes, so that when you eat the salad it fills your whole mouth with flavor. A tomato can give sweetness; maybe you want something peppery, like arugula, or something aniseed, like raw fennel, which is so underused in salads in the UK. And remember that salad leaves all have different flavors and textures, so it is good to include a mixture.

I don’t like to see ready-prepared salads and vegetables in supermarkets, though – all those bags of mixed leaves, looking perfect thanks to a little cocktail of pesticides and kept going in their “modified-atmosphere” bags, alongside packets of shelled peas, and beans with their tops and tails cut off. Vegetables and leaves begin to lose some of their nutrients, especially vitamin C, the moment they are plucked or cut up, so who knows what value is left in prepackaged ones by the time they reach your plate?

I know not many of us are lucky enough to do what my grandmother did and just go out into the garden and pick a few heads of this and a head of that, depending on what my granddad had planted. But I would far rather buy a variety of different salads in their entirety at a farmers’market, from someone I know doesn’t use chemicals, and mix them myself. What I get especially mad about are those bags of romaine lettuce with their little packets of ingredients ready to make Caesar salad. If you simply buy a head of lettuce, make up a vinaigrette and grate in some cheese, you achieve double the quality at half the price.

If you are serving salad leaves with hot ingredients – for example, seared scallops or grilled porcini mushrooms – try to use the more robust leaves, such as wild arugula, which will not “cook” and wilt too quickly. And if you are serving your salad on individual plates and want it to look good, arrange the heavier ingredients on the plates first, then the lighter ones, such as leaves, on top.

Finally, you need careful seasoning and a good vinaigrette or other dressing to pull all the different elements together. Again, I love the way Thai people make dressings out of crushed peanuts, fish sauce and lime juice to bring everything together. That is what we are aiming at – to transform an assembly of ingredients into something exciting.

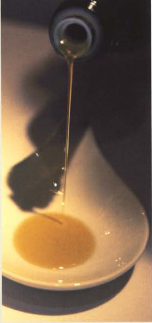

“Liquid gold”

In Italy, olive oil is still considered something you buy from someone you know, either direct from a small local producer, or via a shop that will probably only stock a few oils, mostly local. The bigger national companies often export more of their oil around the world than they sell at home in Italy. Margherita, my daughter, asked me one day why, when Noah sent one of the doves out from the ark, it flew back with an olive branch in its beak; and I explained to her that the olive – and the oil that is pressed from it – has always been seen as the fruit of peace, and often prosperity.

Olive oil has been made since around 5000 B.C., first in ancient Greece and then in countries like Israel and Egypt, eventually being introduced to Italy by the Greeks around the eighth century B.C. The Romans planted olive trees everywhere throughout their empire. It seems strange that something that has been made and used since ancient times should almost have been reinvented, at least outside the Mediterranean countries, over the last twenty years or so, since everyone started talking about its health-giving properties. Good extra virgin olive oil is rich in antioxidants that can help fight bad cholesterol and prevent heart attacks and cancer. Even in ancient times, however, people understood that olive oil had special properties, that it was good for the body, and in some cultures it has an almost mythical significance. Homer called it “liquid gold"; and it was considered so precious that champion athletes at the Olympic games were presented with it instead of medals. Olive branches were even found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, and Roman gladiators used oil on their wounded bodies. And as far back as A.D 70, the Roman historian Pliny the Elder wrote that “olive oil and wine are two liquids good for the human body.”

The highest grade of oil, extra virgin, means first that it is “virgin” olive oil, that is, the liquid from the fruit is extracted purely by cold pressing – with no heat or chemicals used. Then, to be “extra virgin” and therefore the best quality, the oil must have less than 1 percent oleic acidity – a higher percentage than this would suggest that the acids had been released because the fruit was damaged or had been roughly handled. If an oil is labeled just “olive oil,” it will be a blend of inferior oil that has been refined, probably using chemical treatment, and virgin oil.

When I was growing up in Lombardia we used very little olive oil, except in salads and minestrone, and what we had was the light gold, fruity, quite delicate oil from Liguria, made from Taggiasca olives, which I still love. There is also a beautiful, sophisticated oil from the Lombardia shores of Lago di Garda, which we use in Locanda. It is made right on the northern limits of where olives can grow and now has its own DOP (Denominazione di Origine Protetta, or Protected Designation of Origin, and any producers who want to use its symbol must meet strict criteria).

In our house in Corgeno, if an olive oil was peppery it was considered a defect, whereas in Britain, since everyone fell in love with Toscana, the deep green, peppery, often prickly oils that characterize that region are more fashionable. When I first came to London, Antony Worrall Thompson was the man at Mánage à Trois – and one of the first to serve little bowls of olive oil with the bread, instead of butter. His idea of oil was the more peppery, the better. Then, when the River Café opened in London, Tuscan oil became even more popular. I remember when I was working at the Savoy; I took a bottle of River Cafá oil home to Corgeno. My dad tasted it and said, “Take it back to England!” Peppery oil has its place, of course, but not for everything: if you steam a delicate fish, like sole, the sweetness of the fish juices can make a strong oil taste almost rancid. And if you use a peppery oil with an equally hot leaf, the two will just clash.

When I cook a dish from a particular area, I like to try the oil that comes from there too; as with all Italian food, local produce – even the oil – determines the flavors. In general, olives that have had more exposure to the sun and more dramatic variation in temperature between day and night give more peppery oils; whereas in more temperate areas, the oil is lighter. Even within a region, though, the character can vary dramatically, and from producer to producer, as so much depends on the variety of the fruit, the altitude at which it is grown, the time of harvest and the care taken in handling the olives. For example, Tuscan oils made from olives grown around the coast, which really soak in the sun, have a different character from those grown in the Chianti hills, which are picked when only just ripe, before the frost, and so can produce young, herbaceous, almost prickly oils. Umbria can make oil that is sweet and fruity, or spicy; Marche and Abruzzo tend to make oils that are similar to Tuscan ones, whereas the ones from Puglia (the biggest production area), Calabria and Sicilia are mostly intense, but they might be almondy or very green and grassy. In Sicilia there is also a rare and beautiful oil made from the Minuta olive, which is unusual for the island in that it is delicate and fruity.

I’m not suggesting you have a kitchen full of bottles sitting around waiting to turn rancid, but it is good to taste a few different good-quality oils from various regions and get to know the flavors that you like. Read the labels carefully first. Just because an oil is bottled in Italy doesn’t mean that the olives have been grown there, too. It hurts my heart to say it, but there is a big scam where olive oil is concerned. We sell millions of liters a year, but we don’t grow nearly enough olives for that. Instead, a poor farmer in somewhere like Spain or North Africa sends his olives to Italy, because the oil is worth more if it says on the bottle that it was “produced” in Italy. That, to me, is completely wrong, because I believe first of all that an oil should have something of the character of the region it comes from, just as a wine should represent its “terroir.” And second, how much quality of the olives is lost in transportation? If the farmer had pressed his olives there and then in his own country, I believe it would be better oil. Because of such problems, scientists are developing amazing tests that use infrared spectroscopy to detect the geographic origin of the oil and could be used in the future to prevent cheating, and the European Commission has tightened up the laws, so that if the olives are not grown in Italy, this should be declared on the label. Also, if a producer wants to say that his oil comes from a particular region, he must meet the strict criteria of the DOP or Indicazione Geografica Protetta (Protected Geographical Indication or PGI), which is awarded to food where at least one stage of production occurs in the traditional region, but doesn’t specify particular production methods.

However, if you want to be sure what you are buying is good quality, look for bottles that state that the oil has been made from olives grown, and preferably handpicked, pressed and bottled on the same estate. Such oils are now being regarded almost like fine wines and, on the best estates, the olives will have been picked at just the right moment, to give the maximum flavor and the optimum level of health-giving polyphenols. They may cost you $30 a bottle, but what is that really – 40 cents per tablespoon? Not that much to pay for something so good for you, that gives so much pleasure and adds so much flavor to a dish. Think how much we pay for some bottled waters, when very little has been proved about their health-giving properties in comparison with olive oil.

When you taste an oil, do so like wine: pour some into a spoon or glass and check the aroma first; there should be a connection with the fruit there, rather than just an oiliness. Then taste, holding the oil in your mouth until you really experience the flavors.

What happens to the fruit on the tree and during the pressing is only part of the story. Just as important is the way it is bottled, and the way we the consumers store the oil, which must be away from heat, light and air, otherwise it will quickly lose its particularity, and its health-giving properties will begin to deteriorate. I only fully understood this from talking to Armando Manni, who makes the most expensive but probably most healthy oil in the world, high up on Mount Amiata in Toscana. His oil has levels of polyphenols that can reach 450mg per liter, compared to 100 to 250mg in other high-quality oils. It is truly beautiful, but most special because, in order to keep the oil as “alive” and valuable to the health as the day it was bottled, instead of using clear glass to show off the color of the oil he uses dark ultraviolet-resistant glass, and only tiny 100ml bottles. So when they are opened the oil won’t deteriorate as quickly as it would in big bottles. He also treats the oil like wine in that he puts in a layer of inert gas to help prevent oxidization, before corking the bottles with a synthetic stopper, rather than cork, which he believes can contaminate the oil.

Cooking with olive oil

The last thing to know about the best extra virgin olive oil is not to use it for frying. For a start, when it is heated to a high temperature it burns easily, changes flavor and the polyphenols begin to lose their properties. Use a lesser olive oil, or even a vegetable, sunflower, or other interesting oil, and keep your extra virgin oil for making dressings, or drizzling over fish or pasta, so that it has the maximum impact.

“A big, big difference to every salad you eat”

As with olive oil, the flavor of vinegar and how much you use of it is quite a subjective thing – if you were to eat a salad dressed the way my mother likes it, you might spit it out, because she loves the flavor of vinegar to come through really strongly. At home in Italy, there will always be one bowl of salad on the table just for her, and a big one for everyone else.

I use very little white wine vinegar; I prefer red wine vinegar, and what I actually like most of all is not officially classed as vinegar in Italy (which by law must have 6 percent alcohol per volume) but is known as condimento morbido (morbido means “soft"). This is brewed in the same way as vinegar but is filtered through wood chips, which smooths it out and takes away some of the sharpness, leaving a “condiment” with lower acidity and alcohol – only 3 percent.

When we talk about good wine, we often think of there being great merit if the production is small and intimate, but with wine vinegar, providing you begin with good grapes, there is no such advantage. You can make millions of liters and still have the same quality; it is like brewing beer. However, you can usually be sure that if you buy vinegar from a producer who makes good wine, the vinegar will also be good quality. People tend to think that it isn’t worth spending a few more pounds on a bottle of good vinegar. But, as I always say when people complain about the price of good olive oil, if you think about how little you use at a time, you are only talking about a few cents, which will make a big, big difference to every salad you eat. And the vinegar isn’t going to go bad, unless you actually put it in the sun with the top off and let it evaporate.

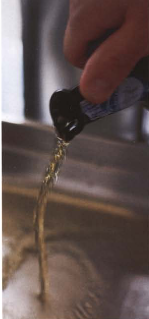

Balsamic vinegar, which comes from Modena and the surrounding region of Reggio Emilia, is something completely different, which I use only occasionally and sparingly. As far back as 1046, a visiting German emperor, Henry II, wrote about a special vinegar that “flowed in the most perfect manner,” and it has been eulogized ever since as a mysterious, precious elixir. Originally, it was taken as a tonic as much as it was used in cooking – balsamic actually means “health-giving.” However, it remained something of a local secret, made in small quantities that you used when a guest came to visit, or at Christmas, but not every day. In Lombardia, I never saw balsamic vinegar until I was about sixteen and started working in restaurants. We didn’t even have any in the kitchen at La Cinzianella. Then, like sun-dried tomatoes, balsamic vinegar suddenly became fashionable all over the world, and people fell in love with it, using it for everything. Because the traditional production in and around Modena was so small, people began manufacturing it commercially to meet the demand – so now there is great confusion about what is the authentic vinegar and what is just an industrial product that resembles it. In America, especially, there are even balsamic “sauces,” “glazes” and “creams” that you can buy in squeezy bottles, like ketchup.

Unlike other vinegars, true balsamic vinegar is made not from wine but from the must of the Trebbiano grape that has been cooked slowly to concentrate it. This is blended with aged wine vinegar, then matured for at least twelve years in a series or family (acetaia) of barrels, which range downward in size, and are made from different woods (typically oak, cherry, chestnut, mulberry, ash and juniper), so that each adds its own character. Each year, as some of the vinegar evaporates, the smallest barrel is topped up with liquid decanted from the next smallest one, and so on, until finally, the last and largest barrel is topped up with freshly cooked must from the new grape harvest. It is a continuous, complex, serious art, which produces a naturally thick, syrupy vinegar with a taste that should have a perfect balance of sweetness and acidity. (The barrels are traditionally stored in attics under the rooftops, where the heat of summer and then the cold of winter are intensified, as this naturally prompts the processes of fermentation and oxidization.)

In 1980 a controlled denomination of origin for the vinegar was set up, and by law, for a vinegar to be called aceto balsamico tradizionale, it has to be produced according to these methods and approved by the Consortium of Producers of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar (Consorzio fra Produttori di Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Reggio Emilia). If you are a producer, you must send your vinegar to them; they taste it blind and, if it is good enough quality and meets all the requirements, they bottle it in their special tulip-shaped bottles. They then mark it with different-colored stamps: red for up to 50 years, silver for a minimum of 50 years, and gold for a minimum of 75 years. Production of this balsamic vinegar is very limited, and for some of the people who supply their vinegar to the consorzio it is almost more of a hobby than a business: some will only make 100 or so bottles a year. We are talking about vinegars that cost up to $200 a bottle, but when you taste the real thing, the experience is extraordinary.

There is another category of balsamic vinegar that is either produced outside the designated region of Reggio Emilia, and so cannot be called “tradizionale,” or is made by people who don’t want to deal with the consorzio – maybe they have such a small production that it isn’t worth their while. Or sometimes, producers of “tradizionale” also make other, high-quality vinegars that haven’t been aged for so long. Such vinegars must be labeled condimento balsamic vinegar and although they can’t be called “tradizionale” they are made using identical methods, so they can be fantastic quality, and are usually cheaper. I have stayed near Modena and seen people go to the local producers with their own bottles, which the guys fill up for them – and it is beautiful vinegar – but, of course, you have to rely on local knowledge to find out where to go.

The big difficulty is over bottles that are just labeled “aceto balsamico di Modena.” Ever since the world “discovered” balsamic vinegar there has been a huge industrial production, which bears no relation to the true artisanal product. The legal definition of this vinegar is very loose. Much of it is only white wine vinegar with caramel added. I could make it for you in a pot in the kitchen in 15 minutes – but what an insult to the people who have been making beautiful vinegar in the proper way for hundreds of years. Some of it, though, has been made in a way that is similar to the traditional methods, using at least some cooked grape must, and aged in wood for at least a few years. So how to tell? Often “aceto balsamico” vinegar comes in elegant bottles, sealed with wax, with beautiful labels that suggest ancient traditions, but it is important not to be distracted by the lyrical descriptions that the producers tend to use, and go straight to the ingredients list. The first thing to be listed should be the must of the grape, and there should be no mention of caramel, or any added flavorings. Look for a vinegar that says it has been aged in wooden barrels – as “aged in wood” can sometimes mean that wood chips have been added as the vinegar ages.

There is yet another type of vinegar, called vincotto ("cooked wine"), which is similar to balsamic, made in a serious way but without the aging and complexity. They say vincotto has its roots in the old Roman tradition of pressing grapes that had been partly dried, then fermenting them to make raisin wine. It became something farmers would make as a sweet dressing for festivals, or as a tonic, but is now being produced commercially, using the Trebbiano grape in the north. As you move further south it is more likely to be made with the Negroamaro and the Black Malvasia, which are left to dry on the vine or on wooden frames before being “cooked” and reduced for 24 hours. The syrup goes into small oak barrels with some of the “mother” or “starter” vinegar from their wine vinegar production, and it is then aged for four years.

In the kitchen at Locanda we use various different balsamic vinegars, and also sometimes vincotto, but for the table we use only the “tradizionale,” which we often dispense with great ceremony, using a syringe. It is very expensive, but used sparingly it will last you a long time. I would say that if you can afford to buy only one bottle of it in your life, it is worth it, because only by tasting the true traditional vinegar can you begin to understand what balsamic vinegar is about. It is something I would like everyone around the world to experience, because then it can be used as a benchmark by which to judge other, less expensive, balsamic vinegars.

Almost everyone likes the taste of a true balsamic vinegar, kids especially. At one time, the only way we could get my daughter, Margherita, to eat a green bean salad was to toss it in balsamic vinegar. It is like a natural flavor enhancer. Good balsamic vinegar needs to be used very simply, though, with specific ingredients. Its combination of sweetness and acidity is at its best with salty, fatty things: so a few drops are perfect with Parmesan, especially the concentrated flavor of an aged cheese. A lovely thing to serve before dinner with an aperitif is just a sliver of Parmesan on a spoon with a drop of vinegar on top. Or sometimes, when we have held parties at Locanda, we have put out half a wheel of Grana Padano cheese, which is similar to Parmesan (see page 209), so that people can pick up small pieces, drizzle some vinegar over it and eat it with a glass of Prosecco. I always keep a good bottle of balsamic vinegar at home and sometimes, if I go home late at night from the kitchen, that is all I have – a big wedge of Parmesan with a little vinegar. Since both the cheese and the vinegar originate in the same region of Italy, there is an affinity there that comes with produce of the same land, and so the combination is very satisfying.

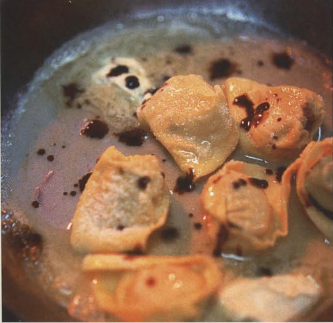

Sometimes we make agnolotti with Parmesan, tossed in a little butter, with a couple of drops of balsamic vinegar added; and I love to serve balsamic vinegar with pork belly, or with calves’liver, in a simple sauce made with golden raisins and nuts (see page 484). A little drop is amazing with plainly cooked wild salmon, and balsamic vinegar and strawberries is another famous combination.

I don’t think balsamic vinegar works with bland food. With a cheese like mozzarella, the effect is wasted, and I wouldn’t usually use it to dress a leaf salad, as it loses its impact, unless you are using strongly flavored leaves like chicory, radicchio or arugula. And I completely disapprove of serving bread with a bowl each of oil and balsamic vinegar – oil yes, but if you dip good bread into balsamic vinegar, you ruin both things. For me it doesn’t work with complicated dishes either. If you were to spoon balsamic vinegar over an elaborate fish dish with lots of different elements, yes, it would add another level of flavor, but again it would be a waste of something special that deserves to be treated with respect.

There is no real Italian equivalent for the word vinaigrette because traditionally, when you went into a restaurant and ordered a salad, they would bring the oil and vinegar and some salt to the table – or if you wanted oil and lemon, you would just ask for olio e limone. Nowadays, if a salad comes ready-dressed, we just borrow the French term. Or we might use the word condimento, which can mean any kind of seasoning or flavoring as well as a dressing; or even aspretto – from aspro, meaning “sour.” We usually use this term when we create a dressing in which there is an element that we have made ourselves – such as our saffron “vinaigrette,” which we would call aspretto di zafferano.

When my brother, Roberto, and I were kids, we were sometimes taken to a local restaurant where dressing the salad was considered a bit of an art. Usually we didn’t want to eat salad at all; we just wanted to watch the waiter perform his ceremony at the table. He would take a silver spoon, put some salt into it, then pour in the vinegar and let the salt dissolve in it. Then he would drizzle a line of oil into the salad bowl and pour in the seasoned vinegar at the same time, so the two met in a stream. Finally, he would put in the leaves and toss everything together in front of us.

The point is that dressing salad leaves should be done at the very last moment before serving, to preserve some crunchiness. Wash the leaves well, trying not to squeeze them, let them drain naturally in a colander, then finish off in a salad spinner. Dress the leaves very lightly so that the dressing just coats them without drowning them and when you toss everything together, really lift up the leaves so that the dressing coats every single one.

If you are dressing a more complex salad that includes other ingredients besides leafy greens, think about their consistency before you add the dressing. It is only the delicate leaves that need to be dressed at the last minute, so if, for example, you are making an arugula and tomato salad, the heavier, denser tomato will need more seasoning – earlier – than the arugula. What I would do is put the tomatoes in the salad bowl with some dressing, season them and leave them for ten minutes or so to soak up the flavors and release the juices that the salt will bring out. Then, at the last minute, I would throw in the arugula and toss everything together, adding a little more vinaigrette if necessary – a lovely thing to do at the table.

I will never understand why people buy ready-made vinaigrette in a bottle when there can hardly be anything simpler than mixing together some good oil and vinegar, seasoning it with a little salt (I also add some water, just to soften the dressing), putting it into a bottle with a cork in it and storing it in the fridge. That’s it. My children make vinaigrette at home without even thinking about it. So how can commercial manufacturers tell us that what they put in a bottle is better? Some of them seem to have invented a machine that leaves the dressing in a state of permanent emulsion, which people think must be a good thing. But all you have to do to emulsify a dressing is shake your bottle of oil and vinegar.

There is, of course, no rule that says you must use olive oil for everything – not even in an Italian kitchen would we be that partisan. Sometimes we use other oils, including walnut and hazelnut, to give a different taste to a salad. Just think about your flavors before you add a very distinctive – tasting oil, so that your ingredients and your dressing complement each other and von have no violent clashes.

The reason this is called Giorgio’s vinaigrette is not that I am doing anything special – millions of people around the world make exactly the same thing. It just happened that when I was at Zafferano there was a young Algerian chef who could never remember which dressing was which, because we used several in our kitchen. We would shout to him, “Vinaigrette!“ and he would say. “What does it look like?” Eventually he stuck a label on each bottle and he called this basic vinaigrette, with oil and vinegar. “Giorgio’s vinaigrette” – so the name has stuck.

I like to mix the vinegar and oil in the ratio of one part to six, but the flavor of vinaigrette is a very subjective thing and everyone has their own ideas. Personally, I don’t like to use a strong Tuscan oil, nothing too peppery and strong for vinaigrette, and you might prefer to add more or less vinegar. It also depends on the quality of the vinegar and its alcohol level. Make up some vinaigrette, taste it and adjust it as you like. The important thing to remember is that if you try it alone, it will taste more powerful than when you mix it with a salad. So, either test it with some greens, or do what I suggest to my chefs: take a little of the dressing on a spoon, put it into your mouth, then suck it in quickly – it should be sharp enough to make you cough slightly, but not so strong that it really catches in your throat.

Buy the best-quality oil and vinegar you can afford, because you can’t put in flavor that isn’t already there. And make up a big bottle, so that you use it all the time. I would be a very happy man if every British family had a bottle of Giorgio’s homemade vinaigrette in the fridge.

Makes about 1 ½ cups

½ teaspoon sea salt

3 tablespoons red wine vinegar

1 ¼ cup extra virgin olive oil

2 tablespoons water

Put the salt into a bowl, then add the vinegar and leave for a minute so the salt dissolves.

Whisk in the olive oil and the water until the vinaigrette emulsifies and thickens.

Pour into a bottle, seal and store in the fridge, where it will keep for up to 6 months. It will separate out again into oil and vinegar, so before you use it, just shake the bottle.

Put the white wine, vinegar and saffron into a pan over low heat and bring to a boil. Simmer until reduced by three-quarters, then remove from the heat, stir in the sugar until dissolved and leave to cool. Whisk in the oil.

Makes about 3 ¼ cups

2 cups plus 2 tablespoons white wine

2/4 cup white wine vinegar

1 level teaspoon saffron strands

1 tablespoon superfine sugar

about ½ cup extra virgin olive oil

Store the vinaigrette in the fridge, where it will keep for up to 6 months in a screw-top jar or bottle – or a plastic squeeze bottle. Take it out of the fridge half an hour or so before you need it, and shake to emulsify before use.

Condimento allo scalogno

Finely chop the shallots, then put them in a bowl and season with salt and pepper.

Makes about 1 cup

2 banana shallots or 4 ordinary shallots

⅓ cup red wine vinegar

⅔ cup extra virgin olive oil

salt and pepper

Add the vinegar and leave to stand for 30 minutes.

Whisk in the oil and use right away.

Condimento all’aceto balsamico

Put the salt into a bowl, then add the vinegar and leave for a minute so the salt dissolves. Whisk the oil into the vinegar.

Makes about 1 ½ cups

1 teaspoon salt

1 cup plus 2 teaspoons balsamic vinegar

about ½ cup extra virgin olive oil

This will keep in the fridge for up to 6 months in a screw-top jar or bottle – or a plastic squeeze bottle. Take it out of the fridge half an hour or so before you need it, and shake to emulsify before use.

Olio e limone

Put the salt into a screw-top bottle or jar, then add the lemon juice and leave for a minute so the salt dissolves.

Makes about ¾ cup

pinch of salt

3 tablespoons lemon juice

⅔ cup extra virgin olive oil

Add the oil, put the top on, and shake well to emulsify. It is best to use this dressing immediately.

Put the egg yolk in a mixing bowl and break it up a bit.

Add the salt and mustard with half of the vinegar and whisk together for a couple of minutes (this is very important as it helps the mayonnaise to emulsify once you start to put in the oil).

Makes about 2 ½ cups

1 egg yolk

pinch of salt

1 teaspoon dry mustard

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

2 cups plus 2 tablespoons vegetable oil

juice of ½ lemon

Slowly start to add the oil, whisking continuously, until it is completely incorporated. If it starts to get too thick, add the rest of the vinegar; and if is still too thick add a tablespoon of hot water – just enough to loosen it.

When the oil is completely incorporated, add the lemon juice and adjust the seasoning to your taste – add a little more vinegar or lemon juice if you like it a little sharper.

“All about balance”

At home, when I cook something that Plaxy regularly makes, my kids often say my version tastes different – the reason, I think, is the seasoning. I was shocked the first time I saw chefs using salt in a restaurant kitchen because the proportions seemed enormous: handfuls were going into every pot, over meat, fish, vegetables. I remember going home to my grandmother and saying: “They use so much more salt than you.”

As a chef, you are taught to see salt in a different way. You have to think about how we taste our food, receiving different sensations in different parts of the mouth. If you underseason, you are taking away a whole layer of flavor; if you overseason, you block out all the other sensations. Salt can also help you experience sweet flavors in a more pronounced way. Heston Blumenthal of the Fat Duck in Bray does an experiment with a glass of tonic water – if you keep adding salt a little at a time, it gets to the point where it tastes sweeter; then obviously if you carry on, the saltiness takes over. At Locanda, we do a tomato “soup” for a dessert with basil ice cream. When we first made it, we served it with sweet sablé biscuits, then we tried it with slightly salty biscuits, and the difference was amazing.

Seasoning is all about balance, so you must be constantly tasting and adjusting. Of course, it is also true that taste is a subjective thing, and I would never be so fussy as to get angry with anyone in the restaurant who wanted to add extra seasoning to their food, as some chefs famously have. I only hope that people taste first.

These days everyone is rightly concerned about the quantity of salt that children, in particular, are eating, but most of the damage is done not when we cook fresh food, but by the salt we often unconsciously eat in processed food. Also, if you taste and season carefully as you are cooking, allowing the salt time to dissolve and do its job of flavoring properly, you will end up using far less than if you taste at the end, panic because everything is bland, and start seasoning crazily.

Most chefs have cut back the quantity of salt in cooking over the years, and looked for different ways of amplifying tastes, for example bubbling up juices and sauces in the pan, so that they reduce and thicken and the flavor intensifies. Also, we are constantly trying to find producers and farmers who value traditional methods and believe that flavor is more important than fast-grown, perfect-looking homogeneous products that will please the supermarkets. So, when you have a carefully and slowly reared, properly hung piece of meat, a terrific vegetable that has not been forced under glass, or a fish straight from the boat, you don’t need to season heavily, or you will distort the essential flavors.

On the other hand, everyone is crying, “Salt, salt, salt!” as if it were a demon, but we all need a certain amount of it for our bodies to function properly. We can take a lesson from the behavior of animals in the wild, whose trails will often lead to natural sources of salt, because it is essential for them to stay alive. I remember reading about the big apes, the ones that are so human that they look like us and have a “spouse” and family – at certain times of the year they will head toward mountains which they know form natural rock salt and lick the salt.

Because we are so used to refrigeration, we underestimate the importance that salt has played in our civilization and politics. As well as keeping the body healthy, and flavoring food, when it was first discovered that you could use it to extract moisture from meat or fish, and therefore cure and preserve foods so you had something to eat year-round, it must have seemed a magical thing. No wonder whole communities were built around the production and trade of something so precious. In Italy, Venezia owes much of its splendor to its position at the center of the salt trade (along with Genova). Roads were built: especially to transport salt; wars were fought over it, taxes raised on it – all of which Mark Kurlansky brings together in his brilliant book called Salt: A World History.

The first proper saltworks date back to 640 B.C., when one of the early Roman kings, Ancus Martius, built an enclosed basin at Ostia and let in seawater, which evaporated under the sun, leaving behind sea salt. The road that the salt traveled in order to be sold was called the Via Salaria, and the soldiers who protected it were often paid in salt, which is where the word salary comes from. If someone didn’t do his job properly he was considered “not worth his salt.” The word salami (pork preserved with salt) comes from the Latin sal for salt, as does salad (it was used to describe the Roman way of adding salt to greens and herbs, perhaps to draw out bitter juices in the way that we do with eggplant, then dressing it with oil and vinegar).

We have Parma ham because people in the region needed to preserve meat, and salt could be brought in from Venezia, with payment in either money or hams. Of course, there was a massive trade in smuggling in order to avoid paying the taxes that were levied on salt. The route the smugglers used is called La Via del Sale (the road of salt) and runs all the way from the Appeninos to Liguria. Nowadays part of the route is used for a fantastic endurance motorbike race, also called La Via del Sale.

What we are talking about is natural sea or rock salt, very different from “table salt,” which is bleached and refined, often has chemicals added and has a harshly salty flavor. I always thought what a great job it would be to spend your days skimming off the perfect little crystals at some natural salt pan, somewhere wild and beautiful. This is the kind of salt you can pack around a piece of meat or fish for baking in the way that has been done for thousands of years. (Originally, you would have dug a pit in the ground, put in the fish or meat in its salt crust, covered it over and built a fire over the top.) As it cooks, the salt crust becomes rock hard, sealing in all the moisture and juices, and gently seasoning at the same time, but without making the cooked meat or fish taste “salty.”

When Thomas Keller, the inspirational chef of The French Laundry in California, came to Locanda to eat, we got talking and he told me about the way he served foie gras with five different salts, including Dead Sea salt and Jurassic salt. When he went back to America he sent me some of the Jurassic salt, which is mined in Utah. It is incredible to think that it comes from a geological layer underneath that of the dinosaurs. At one time most of North America lay below a shallow sea, which evaporated over millions of years, leaving behind the salt, then in the Jurassic era volcanoes erupted around the old seabed and sealed the salt inside volcanic ash. The salt comes in a pinkish block that you have to grate, and it has a flavor that is amazing; it almost has an almost fizzy quality. We sprinkled it over some carpaccio and served it with nothing else but a piece of lemon and it was beautiful.

When you are seasoning, it is important to remember that salt has the function of extracting moisture as well as flavoring. You need to season meat or fish before you start to cook it, because once the outside has been sealed, your salt and pepper won’t penetrate in the same way. However, once you season a piece of meat or fish with salt, it will start to “sweat” out its juices, so if you do this too far ahead of cooking it the flesh will become tougher. The trick is to season your meat or fish with salt and pepper just before you cook it – then, especially if you are cooking it over a high heat, the meat will be properly seasoned, and the salt and pepper will help form a nice “crust” around the outside of the meat, while the juices will be sealed inside.

With some dishes you also need to consider how much salt is contained in the ingredients you are cooking before you add any extra. I will taste and season a risotto, for example, only right at the end, because you are working with a lightly seasoned stock all the way through, which will intensify in flavor as it reduces, and then it will be finished with pecorino or Parmesan, which is also quite salty.

And remember that when you cook beans or pulses in water, unlike other vegetables, they should be seasoned only at the end of cooking, as the salt will draw the moisture from their skins and toughen them up if you put it in at the beginning.

At home, we always have a pot of sea salt crystals in the kitchen, which we keep away from the heat and moisture from the steam around the cooker, so that it keeps dry. Then we put a little of it into the grinder at a time.

Always also use freshly ground black pepper, which has much more warmth and aroma and a cleaner taste than white pepper. As with all spices, the flavor is held in the volatile oils inside the peppercorns, which are quickly lost once they are released; so ready-ground pepper, especially if it is exposed to warmth or sunlight, will lose its potency very quickly. I hate big pepper grinders, not only because they remind me of the way many “Italian” restaurants were when I first came to England, but because everyone fills them up and leaves them for years. I prefer small ones that you can fill with a couple of teaspoonfuls of freshly bought peppercorns on a regular basis.

“Such an Italian flavor”

Parsley and garlic… the mixture has such an Italian flavor. It has become a joke in our house that whenever I am wondering what to cook – “Shall I do this? Shall I do that?” – Plaxy always tells me, “Just do your parsley and garlic!” She knows that whatever I do, I will use them, and also that by the time I have stopped talking and finished chopping, I will have decided what I am going to cook.

Every morning in the restaurant kitchen, one of our jobs is to chop parsley and garlic, ready to sprinkle into dishes whenever needed. We put the garlic cloves on a chopping board and squash them to a rough paste with the back of a knife. Then we put the parsley on top and chop it quite fine, so that the crushed garlic is chopped too. That way the garlic becomes almost a pulp, and it releases its flavors into the parsley and vice versa.

By parsley, I mean flat-leaf parsley, not the curly sort that was once the only kind available in the UK and the U.S. The first time I saw curly parsley, I thought it looked beautiful – but then it was the nouvelle cuisine era.

Now I can’t imagine cooking with anything else but the flat-leaf variety, which has a much more refined flavor – though I have had a few discussions about the merits of curly parsley with Fergus Henderson of St. John restaurant. A big champion of English food, and one of the few chefs I know who loves to use the curly variety, he persuaded me to try it chopped in a salad, and it wasn’t bad. Not bad at all.

Caponata is a Sicilian dish of eggplant and other vegetables, cut into cubes and deep-fried, then mixed with golden raisins and pine nuts, and marinated in an agrodolce (sweet-and-sour) sauce. In some parts of Sicilia, it is traditional to mix in little pieces of dark bitter chocolate. Because it is such a southern dish, I had never even tasted it until I started cooking at Olivo. Then, one day when we were looking for something sweet-and-sour as an accompaniment, I found the recipe in a book and I remember thinking: “This will never work!’’ But we made it, the explosion of flavor was incredible, and it has become one of my favorite things. You can pile caponata on chunks of bread, or serve it with mozzarella or fried artichokes (see page 70). Because it is vinegary, it is fantastic with roast meat, as it cuts through the fattiness, particularly of lamb. Traditionally it is also served with seafood – perhaps grilled or fried scallops (see page 108), prawns or red mullet. With red mullet, I like to add a little more tomato to the caponata.

We often cut some fresh tuna into 1 ½-inch dice and either sauté it in olive oil or grill it until it is golden on the outside but still rare inside (to test whether it is ready, cut open a piece and it should be a nice rose color in the center). Then we add the tuna to the caponata just before serving and toss everything together well.

If you don’t like fennel or celery, leave them out and increase all the other ingredients slightly. Keep in mind that this is not a fixed recipe; it is something that is done according to taste and you can change it as you like.

1 large eggplant

olive oil for frying

1 onion, cut into ¾-inch dice

vegetable oil for deep-frying

2 celery stalks, cut into ¾-inch dice

½ fennel bulb, cut into ¾-inch dice

1 zucchini, cut into ¾-inch dice

3 fresh plum tomatoes, cut into ¾-inch dice

bunch of basil

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon golden raisins

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon pine nuts

about ½ cup extra virgin olive oil

5 tablespoons good-quality red wine vinegar

1 tablespoon tomato passata

1 tablespoon superfine sugar

salt and pepper

Cut the eggplant into ¾-inch cubes, sprinkle with salt and leave to drain in a colander for at least 2 hours. Squeeze lightly to get rid of excess liquid.

Heat a little olive oil in a pan and gently sauté the onion until soft but not colored. Transfer to a large bowl.

Put the vegetable oil in a deep-fat fryer or a large, deep saucepan (no more than one-third full) and heat to 350°F. Add the celery and deep-fry for 1 to 2 minutes, until tender and golden. Drain on kitchen paper.

Wait until the oil comes back up to the right temperature, then put in the fennel. Cook and drain in the same way, then repeat with the eggplant and zucchini.

Add all the deep-fried vegetables to the bowl containing the onion, together with the diced tomatoes.

Tear the basil leaves and add them to the bowl with all the rest of the ingredients, seasoning well. Cover the bowl with plastic wrap while the vegetables are still warm and leave to infuse for at least 2 hours before serving at room temperature. Don’t put it in the fridge or you will dull the flavors. It is this process of “steaming” inside the plastic wrap and cooling down very slowly that changes caponata from a kind of fried vegetable salad, with lots of different tastes, to something with a more unified, distinctive flavor.

People think deep-frying is easy, but it isn’t at all, and it can be dangerous. If you shallow-fry something you can touch and turn it easily, but with deep-frying you enter into a contract with the oil in which you have no control. Little home fryers are brilliant because they have safety mechanisms and you can set the temperature, which is so important, to avoid having something that is burnt on the outside and raw on the inside, or vice versa. If you must use a pan, never put more than 6 cups in a 1- gallon pot because not only will the level rise when you add your ingredients, but oxygen is released and so the expansion will be even greater. And use a thermometer.

Insalata di radicchio, prataioli e gorgonzola piccante/dolce

In Lombardia, we call Gorgonzola erborinato, after the “parsley green” color of the mold. In the old days, it was made in damp caves around the Lombardia town of Gorgonzola, where it was left for up to a year so the mold developed naturally. Nowadays the mold is introduced by piercing the cheese with steel or copper needles when it is around a month old. In the restaurant, we use 90-day-old Gorgonzola, which is harder and saltier (piccante), instead of the young creamy one (dolce), but you could use either.

2 small round heads of radicchio

2 tablespoons olive oil

4 handfuls of button mushrooms, sliced

½ wineglass of white wine

2 ¼ ounces (about ⅓ cup) mature Gorgonzola cheese

2 to 3 tablespoons mayonnaise (see page 53)

1 garlic clove handful of flat-leaf parsley

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

salt and pepper

Clean the radicchio, removing all the white parts from the base and keeping the small red leaves whole. Tear the larger leaves into halves or quarters.

Heat the olive oil in a pan, add the mushrooms and sauté until golden. Add the wine and stir until that has evaporated. Season, remove from the heat and keep warm.

Break up the Gorgonzola and melt it gently in a bowl placed over a pan of simmering water until it is creamy. Allow to cool slightly and mix into the mayonnaise to make a dressing.

Squash the garlic to a paste with the back of a knife, put the parsley leaves on top and chop it, so that the two combine.

Season the radicchio and toss with the extra virgin olive oil. Arrange the radicchio in nests on 4 serving plates, so the whole leaves are around the outside. Mix the parsley and garlic with the mushrooms and spoon into the middle. Drizzle with the Gorgonzola dressing and serve.

Insalata di porcini alla griglia

This is a dish for those times when you go shopping and just happen to see fantastic fresh porcini (see page 232). Whenever I find them, I buy 2 pounds, use some for a risotto, put some in a veal stew and keep back the most beautiful ones to grill for this salad. In the restaurant, we serve quite a smart porcini salad with reduced veal stock and beurre fondu drizzled around the plate. This is too complicated to do at home, but it is just as good simply to grill the mushrooms, dusted with chopped garlic and parsley, as suggested below, and then rub your plates with a cut lemon before you put the porcini on them.

½ garlic clove

2 handfuls of flat-leaf parsley

10 ½ ounces small porcini mushrooms (ceps) (see page 239 for preparation)

a little extra virgin olive oil

½ lemon

2 handfuls of mixed green salad leaves

5 celery stalks, cut into matchsticks

1 ¼ ounces Parmesan

4 tablespoons Oil and lemon dressing (see page 52)

small bunch of chives, cut into batons

salt and pepper

Preheat the grill or, preferably, a ridged griddle pan. Squash the garlic to a paste with the back of a knife, then put the parsley on top and chop it so that the two mix together well.

Cut the mushrooms lengthways into slices about ¼ inch thick (cutting through the stem, too) and reserve any trimmings. Season the slices and brush with extra virgin olive oil, then dust with the parsley and garlic mixture.

Grill the porcini slices, turning them over to cook the other side as soon as they start to brown. Rub the serving plate or plates with the halved lemon and arrange the porcini on top.

Slice any reserved porcini trimmings very fine and mix with the salad leaves and celery strips. Grate about 2 tablespoons of the Parmesan, season the salad and mix with the grated cheese.

Toss the salad with the dressing, then pile it on top of the porcini and scatter with the chives. Shave the rest of the Parmesan and sprinkle it over the top.

“A fish that deserves respect”

Sometimes it seems to me that people in the United States and Britain don’t think of the anchovy as a fish at all but as something in a category all of its own, something that goes on top of pizza or into a salade niςoise. In Italy, though, we have great respect for anchovies. The ancient Romans ate them fresh and it is thought that, together with sardines and mackerel, they also saturated them in salt and let them ferment in the sun, sometimes adding herbs and wine, to make a sauce called liquamen for seasoning food – rather like Thai fish sauce. In the north, they sometimes add anchovies to osso buco. In Sicilia, they like to cook them al beccafico – boned, sprinkled with a little vinegar, covered in bread crumbs and herbs and grilled or baked. In Trentino–Alto Adige, they specialize in speck (the hind leg of the pig, cured in salt, pepper, juniper and bay, then smoked over wood and juniper berries), which they serve with anchovies mashed into butter. In the south, anchovies are used in a sauce for pasta.

When I was a child, at Christmas and on special occasions, such as my granddad’s birthday, we used to have anchovies in salsa piccante (the only time I ever tasted chile pepper when I was growing up), which came in small gold tins decorated with three little dwarves, like the ones in Snow White, wearing yellow, red and green hats. They were made by a company called Rizzoli in Parma, which still produces them, in a sauce it has been making to a secret recipe for a hundred years. Whenever I go to Italy and see the gold tins in a delicatessen, I still can’t resist them.

Another thing I adore is dissolved or “melted” (sciolte) anchovies. You put some anchovies into a pan with some olive oil, turn on the heat and warm gently to “melt” the anchovies, rather than fry them, or they will lose their flavor. If you buy a pound of salted anchovies, rinse off the salt, dry them, then “melt” them like this, you can transfer the paste to a sterilized jar and cover it with a layer of olive oil. It will keep for six months in the fridge, so you can take it out and spoon some over pasta whenever you want. “Melted-down” anchovies are the basis of the famous Piemonte autumn dish bagna càôda, which literally means “warm bath” (see page 146). Like so many Piemontese recipes, it is a dish that needs lots of people to gather round the table with a bottle of good Barolo and share big plates of vegetables, usually raw but sometimes boiled, which you dip into the bagna càôda. It is made with anchovies, garlic (soaked first in milk), oil and butter, and is kept warm in an earthenware pot over a spirit flame in the middle of the table. Sometimes, when only a little of the sauce is left, people break in some eggs and scramble them. Such a fantastic, convivial thing to do.

It is a funny thing that Piemonte, one of the only regions of Italy that doesn’t touch the sea, has a dish based on anchovies as one of its specialties. The reason is historical. About 300 years ago, the Piemontese people harvested salt and made butter in the mountains. These were traded along the ancient salt routes in return for anchovies from Liguria. A traditional thing that many Piemonte bars do in the early evening is to put out little sandwiches made with butter and anchovies, which you can eat with a glass of wine. Even now, there are still associations of anciue (anchovy sellers) in and around the old trading town of Val Maira that hold dinners to celebrate the relationship between salt, anchovies and butter.

In British fish markets, you rarely find the blue-green and silver fresh anchovies. So you usually have to buy them either still on the bone and preserved in salt (the fish are layered with sea salt in small barrels), or filleted and preserved in olive oil. Frequently, though, the oil is cheap and tastes rancid, and if the fillets are in upright jars they are squashed in so tightly that the ones in the center become mashed and broken (the fillets laid flat in tins are better), so I always prefer to buy the ones in salt. I have to admit that I buy Spanish ones, because the quality is so good. You have to soak them first in water to get rid of excess salt, then take out the bones and pat the fish dry. Then you can either marinate them in good olive oil, a little vinegar and some chopped herbs and serve them as part of an antipasto, or use them in whatever recipe you want.

Insalata di puntarelle, capperi e acciughe

Puntarelle (Catalogna chicory) is difficult to get in this country, but beautiful, especially raw, rinsed and kept in a bowl of ice cubes to get rid of the bitterness. It’s a real thirst-quencher. When people ask me what puntarelle is like, I usually compare it to fennel, because they share very similar characteristics, apart from the aniseed flavor of fennel. The puntarelle season runs from October to January or February, but as time goes on it can become more bitter and woody, so you need to wash it much more, and also eventually discard the tougher parts. Otherwise, the closest you can get is regular chicory cut into strips, but don’t put these in ice.

When we make this dish, we usually discard the outer leaves of the puntarelle, but, if you like, you can keep them to serve as an accompaniment to fish or meat, especially barbecued meat. Blanch the leaves briefly in boiling salted water, then drain, chop and sauté in a little olive oil. Mix with some toasted pine nuts and some golden raisins that have been soaked in water for half an hour or so to plump them up. You could even add the mixture to this salad – spoon it onto your plates first, then arrange the salad on top.

2 tomatoes

2 heads of puntarelle (or chicory)

8 anchovy fillets

2 tablespoons baby capers (or 3 tablespoons larger capers)

small bunch of chives, cut into batons

4 tablespoons Oil and lemon dressing (see page 52)

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

salt and pepper

Blanch the tomatoes, skin, quarter and deseed (see page 304).

Discard the outer green leaves of the puntarelle, slice the hearts very thin lengthways, then wash well under cold running water until the water is clear – the puntarelle will turn the water green at first – to take away some of the bitterness. When you serve the puntarelle it needs to be really crisp, so put it into a bowl with some ice cubes and leave in the fridge for a couple of hours, adding more ice if necessary, and it will curl up beautifully.

Drain the puntarelle well and pat dry. In a bowl, mix together the tomatoes, anchovies, capers, chives and finally the puntarelle. Season, but be careful with the salt, as the anchovies and capers will add quite a lot of saltiness. Toss with the oil and lemon dressing and serve as quickly as possible, drizzled with the olive oil.

“Unique and pungent”

Capers are beautiful things, with a unique pungent flavor, which we use a lot in Italy, especially with antipasti, but also with meat and fish. When Prince Charles talked about boiled mutton with caper sauce at a celebration of English mutton and they said this was an old English sauce, I was amazed. Of course you see capers in jars all over the world these days, but I had always thought of fresh capers as Italian. Then I did some research, and found out that in the 1700s there were merchants who brought Marsala wine and capers over to England from Italy.

The best capers come from the islands of Salina and Pantelleria off Sicilia, with their volcanic soil and hot climate. The capers, which are not seedpods, as many people think, but tiny tight flower buds of the shrub Capparis spinosa, grow everywhere. The shrubs are planted in special trenches which are dug to hold them firm and protect them from the sirocco wind. And of course, the people of each island say that their capers are the best.

Like saffron, capers are harvested by hand, in the late spring to early summer, before they begin to open. It is only if you pick them at just the right time that you get the proper, stratified texture. If the bud hasn’t developed enough, they are too compact. Like olives, they must be cured, as they are too bitter to eat as they are. The best are laid down on canvas outside, to get the sun for a couple of days, then layered with salt in wooden barrels, though they can also be put into brine or wine vinegar.

We use them in tartar sauces, hot caper sauces, sweet-and-sour sauces and salsa verde, and serve them with any kind of dish where you want their saltiness and special flavor to cut through a fatty ingredient. Sometimes, also, we soak them for 24 hours, then crush them, and fry them as a garnish for fish dishes. It is always best to add capers to dishes at the end if you are using them in cooking, or they will be too strong.

If the buds are allowed to stay on the bushes, they open into beautiful white flowers that seem to turn the whole island into a sea of white, before developing into fruit, which we call the caper berry, or cucunci. They look a little like green olives on stalks, but when you cut them in half they are full of tiny seeds. They have a flavor similar to capers but are less intense. Sometimes we combine capers and caper berries in the same dish, as in Monkfish with walnut and caper sauce (agrodolce, see page 426) in which the caper berries go into an arugula salad.

Insalata di endivia e Ovinfort

Ovinfort is a fantastic Sardinian blue cheese that didn’t exist ten years ago. Now I think it beats any French Roquefort – though I would say that, wouldn’t I? In the north of Italy we are more used to blue cheeses made from cow’s milk, but this is made from very high-quality sheep’s milk and matured for 90 days, so it has quite a strong spicy flavor. People sometimes forget that cheeses have seasons – like every other natural product – and this one is available most of the year except between September and mid-December, when the ewes need their milk for their lambs. If you can’t find Ovinfort, you could use a hard Gorgonzola, or even Roquefort – just don’t tell me.

If you want to serve this dish for a party, you could use each chicory leaf to hold the pear and cheese. Drizzle a little mayonnaise into each leaf, put a slice of pear on top, followed by a slice of cheese, and let everyone help themselves.

Peel, quarter and core the pears, then slice them thin lengthways.

Cut the base off each head of chicory, so that the leaves come away. Mix the mayonnaise with the mustard and add 2 to 3 tablespoons of hot water to loosen it up enough to be able to drizzle over the salad.

Put the chicory leaves in a bowl, season and toss with the vinaigrette. Put a layer of chicory on each serving plate, followed by a laver of pear, then more chicory. Drizzle with the mayonnaise and, using a potato peeler, shave the Ovinfort over the top.

2 ripe pears, such as Cornice

2 heads of yellow chicory and

2 of red chicory (if possible, otherwise 4 yellow)

2 tablespoons mayonnaise (see page 53)

1 teaspoon dry mustard salt and pepper

2 tablespoons Giorgio’s vinaigrette (see page 51)

5 ¼ ounces Ovinfort cheese (or mature Gorgonzola)

“Beautiful, purple, perfect…”

In the restaurant kitchen we get through one box of baby globe artichokes a day when they are in season in the spring – usually carciofi spinosi from Sicilia or the purple violetta di chioggia. They are such beautiful things, less intensely iron-flavored than the bigger ones, so they make a perfect raw salad. Slice them very thin, mix with some salad leaves, season with salt and pepper, and dress with a little lemon juice or vinegar and oil mixed with a tablespoon of grated Parmesan. Finish with a handful of chopped chives and some shavings of Parmesan over the top – beautiful.