“The Italian risotto is a dish of a totally different nature, and unique.”

Elizabeth David, Italian Food, 1954

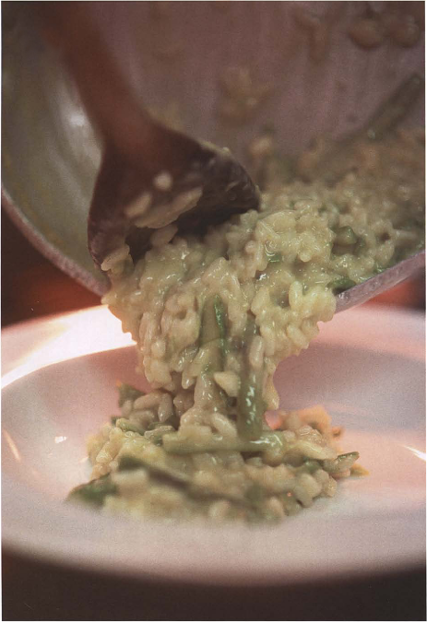

My grandmother’s sister left Italy in the fifties and went to live in Boston, where she married an Italian. When they came home some thirty years later, she always used to complain, “The risotto isn’t good anymore,” because in the time she had been in America the way we prepared risotto had changed. She still remembered how, as a child, she would put a fork into the rice and it had to stand upright; if the fork fell down, it wasn’t a good risotto. Whereas now, in most regions of Italy and especially in the restaurant world, when we think of risotto we have in mind a dish that has a gorgeous soft, loose texture, so if you tilt the plate, the risotto ripples in waves, which we call all’onda.

These days, one of the most important stages of making a risotto is considered to be the mantecatura, which comes from the Spanish word for butter, mantequilla (the Spanish influence in the north dates from Renaissance times, when Lombardia was ruled by the Spanish). It means the beating in of butter and cheese right at the end of cooking, to give the risotto that fantastic creaminess. In my aunt’s day, however, most families couldn’t afford to use so much butter and cheese, so the risotto was quite stiff and unyielding.

In Elizabeth David’s day, risotto was seen as a warming dish very much of the north, where the main rice crop was cultivated (the word risotto comes from the Lombard dialect, even though there are not many rice fields in Lombardia itself; they are in lower Piemonte, on the other side of Lago Maggiore). In Italian Food, she wrote that rice is to the northern provinces of Italy (Lombardia, Piemonte and the Veneto) what pasta is to the South. However, after the Second World War, there began to be a fairer sharing of the land that had once been owned by the rich and cultivated by the poor, and more small companies began to produce rice.

Distribution of food was better throughout the country, so pasta spread to the north, and rice to the south, and people started crossing varieties of rice in order to cultivate different shapes and properties, which began to be seen as just as important in Italian cooking as a particular shape of pasta. And, gradually, all over Italy they began to create their own recipes, which, as always with Italian cooking, changed from city to city, village to village, and home to home. So, eventually, from being just a dish of the north, risotto has come to represent a little bit of all Italy. There is a saying where I come from that even the Colosseum in Roma is stuck together with risotto – one of our many northern political jokes, that it is the money of the north that holds the country together.

In some parts of Italy, though, particularly the central regions and the south, where olive oil is used much more than the dairy products that are so abundant in the north, you will still find risotto that resembles the stiff rice dish that my great-auntia remembered. When I was on vacation with the family in Calabria a few years ago, I remember there was a little bar on the beach by our hotel that was run by a woman who cooked risotto that she ladled out into domes on each plate, and that was the shape it stayed until you worked your fork into it.

By contrast, in the coastal areas such as Venezia, for as long as they have made risotto it has been served all’onda, probably because traditionally their recipes use more fish and seafood, and with such delicate ingredients you don’t want heavy, starchy rice. Others say, more romantically, that around the coast the risotto ripples to mimic the waves of the sea.

There are very few other ways Italians eat rice than in risotto. We rarely use boiled rice, for example, except in insalata (in salad) or in soup – though in Sicilia they traditionally make arancini with boiled rice. Arancini are deep-fried rice balls, about the size of a small tennis ball or orange (arancini means “little orange” ). Often the rice would be mixed with saffron to give it an “orange” color, then it was molded around traditional fillings of meat or ham and peas, dusted in flour, dipped in beaten egg and finally in fine bread crumbs, and deep-fried until the rice balls were golden. Now arancini are made all over Italy, and very often with saffron risotto, rather than boiled rice, sometimes with pieces of mozzarella mixed in (see page 262). You will see them being fried by sellers on street corners, inevitably the mama doing the cooking and the son taking the money. And, around Napoli, they make a more pear-shaped arancini, which they reckon are more appealing and easier for women to eat delicately.

Occasionally, because of its high starch content, rice is used in other dishes as a thickening agent. In Liguria, they have torta di verdura, a pie, or “cake,” made with green vegetables. They make a pasta with flour and water, then take whatever green vegetables they have – like zucchini, spinach or borage – chop them up, take two or three handfuls of rice and mix them in. Then they roll out the pasta quite thin, lay one piece on top of the other, put in the vegetables and rice, lay two more sheets of pasta on top, seal the edges with a little beaten egg or water, brush it with beaten egg and bake the “pie” in the oven. As it cooks, the vegetables release their water, which is absorbed into the rice, and the starch binds the filling together.

I never saw rice used in a dessert until I came to England. When I first saw them making rice pudding at the Savoy in London I was shocked, and when I tasted it I reacted with complete amazement: it was such an alien flavor: rice with milk and sugar and vanilla, which they served with quince … very weird. Once I got used to it, though, I thought it was fantastic. It reminded me that even an ingredient you think you know so well can surprise you, and later at Zafferano, for fun we started to make a “pudding risotto” for the dessert menu, a variation of which we still serve now, at Locanda (see page 552).

To most Italians, though, rice means only the savory risotto they have grown up with. What makes a risotto a risotto – and quite different from any other rice dish in the world – is the way it combines the al dente rice (al dente means “firm to the bite”) with the starchy creaminess that enfolds it. Even the famous French food writer Escoffier, in one of the few mentions he made of Italian cooking, declared risotto to be a completely Italian affair that could not be compared to anything else he knew, a sentiment with which Elizabeth David obviously agreed.

I could never imagine having a restaurant without serving risotto; it has always been such a big part of my life. In our house in Corgeno, risotto was a part of the cycle of preparing and cooking food that went on all the time. One of the secrets of a good risotto is good stock, so if my grandmother cooked a chicken, she always took the time to use the bones to make the stock for the risotto.

When the wild mushrooms were around, we would have mushroom risotto, or sometimes it would be an even simpler affair. My granddad would come in from the garden with some fennel and a big bunch of parsley, and my grandmother would make a fennel risotto, then chop the parsley with a mezzaluna and add it with the butter at the end – such a wonderful fresh flavor. If there was asparagus she would boil it up, putting the trimmings into the stock, then make a risotto simply with butter and grana cheese and serve the asparagus on the side – not so very different from the way we do asparagus risotto now in the restaurant. And, once a year in the white truffle season, my brother and I would go off to Alba with my granddad to buy a precious truffle. Then, when we came home, there would be a little ritual by the stove: my granddad would hand the truffle to my grandmother as she finished the risotto, she would grate the brown sweaty ball over it like Parmesan, and the fragrance that filled the kitchen would be incredible.

Sometimes for our special Tuesday lunch with the whole family she would make her famous risotto allo zafferano, in the traditional way with powdered saffron, rather than strands, which I never saw until much later. I remember the saffron jar in my grandmother’s kitchen. It had a picture of a chef with a big hat on it, and inside were lots of small paper envelopes, which you opened very carefully at one end and then tapped the other, so the rich yellow powder flowed out. My granddad used to say it cost as much as gold, and the flavor and the color were so vivid and fantastic, they have stayed with me all my life. So much so that when I opened my first London restaurant, I could think of only one name for it: Zafferano.

Once upon a time in Italy, the main culture of rice was the variety known as arborio, which was the typical rice cultivated in the feudal Lomellina region, the first recognized area to be planted with rice in the eighteenth century. When I was drafted into the army in 1982,1 stayed near the plantations: so beautiful, with their light green plants separated into squares surrounded by canals and dykes. These days the harvesting and weeding are done by machine, but once it was all done by mondine, women who spent their days with their backs bent double, their bare feet in water, singing traditional communist songs, which we all learned when we were young.

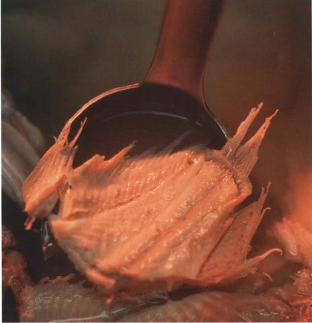

The area around the rice fields was also home to frogs and snails that would find their way into local stews. And now, one of the artisan growers we buy our rice from, Gabriele Ferron in Isola della Scala near Verona, is doing a fantastic thing, raising carp in the flooded fields where the rice grows. The fish eat a lot of the vegetation so they help to keep the weeds down and the water healthy. At the same time the carp grow big and fat. So when the time comes to harvest the rice they also take out the carp and have a big party with risotto and fish.

In a beautiful risotto, within the softness of the finished dish the grains of cooked rice will look like pearls, much as they did when they were raw. This is because risotto rice, which is the type known as japonica, is made up of two different starches. On the surface is a soft starch called amylopectin, which will swell and partly dissolve during cooking – so some of the starch will be absorbed into the rice, making it creamy. Then inside the kernel there is a firmer starch called amylose, which shouldn’t break and which will keep the rice al dente.

There are three grades of rice for risotto: semifino, which is the smallest; fino; and superfino, the largest. Then within each grade, there are different varieties. The three major varieties are arborio, carnaroli (both superfino) and vialone nano (nano means “dwarf”), which is a semifino. Increasingly, people are producing new varieties, such as bal do, a superfino that cooks a little quicker, or trying to invent more and more pretreated, precooked and preflavored rice. One of the popular ideas is to temper the rice by bringing it up to a certain temperature to harden the outside, in order to stop the grains from overcooking and help them hold their shape. Personally, I don’t believe in any of that stuff. The more you treat a grain of rice, the more you lose the starch that is the whole essence of risotto. And surely, if you have a jarful of pure, good-quality risotto rice in your kitchen and you cook it properly, what could be any better than that?

Each type of rice acts in its own way during cooking – and the quantity of each starch it contains is important. If it is very high in surface starch, and you are not careful, the risotto can become too sticky; whereas if it is high in the inner starch, each grain can absorb more liquid, helping to keep the risotto creamy rather than heavy. Of course, every region and every cook will tell you that one variety is better than another for their kind of risotto. I grew up with arborio. It was what my grandmother used, and it is still the rice most people use to cook risotto at home. It was only much later that I started using any other sort of rice, when I left college and began working at a local restaurant on the shores of Lago di Varese, called II Passatore, where the chef was Corrado Sironi. II Passatore was the only restaurant in the area that had a big brigade, twelve cooks, and it was the first time I saw a head chef who didn’t use his own hands, only his knowledge, to teach and direct other people. I never felt that Sironi had just learned his techniques from a piece of paper at college; cooking came naturally to him. Most of all he was famous as the Risotto King, and he was the one who showed me the importance of the grain in a really, really soft, all’onda risotto, which a customer would think quite special.

In the restaurant world, people are looking for more elegance – you don’t want to be served something that looks like a rice pudding – and arborio contains the highest level of the surface starch, amylopectin, so it gives out more starch than it absorbs, making a quite sticky, dense risotto in which the grains have a tendency to lose their shape a little. Sironi taught me that it is best to keep it for soup and use either vialone nano or carnaroli, depending on what kind of risotto you are making.

Vialone nano has a quite round, thick grain that contains high levels of the inner starch, amylose, so it is capable of absorbing a lot of liquid. When you cook it, it becomes translucent on the outside, leaving the kernel inside looking like a pearl, but the tips of the grain can smooth out and lose their shape a little. So it is best suited to more starchy risottos that have robust ingredients mixed into it, as the kernel is less likely to break as it is tumbled about.

Carnaroli is a very thin, very long grain rice, which is lighter and starchier than vialone nano, but because it has a good balance of the two starches – amylopectin and amylose – it becomes almost totally translucent and pearly when it is cooked, but also holds its shape really well, and absorbs enough liquid to give the risotto a lovely creaminess. We use it in simpler, more elegant risottos, such as saffron risotto and seafood risottos, in which you have only a few added ingredients, or something delicate that goes in at the last minute.

A good stock is important for risotto, and the flavor of your stock will determine the taste of the finished dish, so it is best to make your own. I know people get nervous about making stock, either because they think it is complicated, or they think they don’t have the time, but a stock is a really simple and very rewarding thing to make. You can make a big batch, freeze it in ice cube trays, then transfer the cubes to bags, which you can keep in the freezer to use whenever you need them. See page 264 for recipes.

So much has been said about risotto. One cook will tell you, “It is easy; what is all the fuss about?” Others will say no two risotti ever come out the same, that risotto is unpredictable, and if you don’t take care you end up with either soup or heavy mush. Well, I suppose all those things are true. It is easy for me to say that making risotto is simple, because I have done it all my life. The truth is it does come out slightly differently each time, but that is part of the joy of it, and it is easy, once you understand the way a risotto works.

Perhaps more than any other dish, you need to make risotto a few times to get the feel of the way it is built up through five distinct stages, to achieve that gorgeous mixture of rich creaminess and bite. What happens is this:

First you need to have a pan of hot stock ready on the burner, next to where you are going to make your risotto.

You begin with the soffritto, which is the base of the risotto. Making this involves sautéing onions – and sometimes garlic – in butter. Usually this is all, but if you are making a risotto with wild mushrooms, say, you might also add a few soaked dried porcini at this stage to enhance the flavor. Or, if you are making a risotto with robust ingredients, like sausage, you might add this to the base as well – but whatever ingredients you put in at this stage must be able to withstand 20 minutes or so of cooking at a very high temperature.

Next you have the tostatura, the “toasting” of the rice in this mixture so that every grain is coated and warmed up and will cook uniformly. At this point, you usually stir in a glass of wine and let it completely evaporate before beginning to add the hot stock.

Now you start adding your stock slowly (a ladleful at a time) and when each addition is almost absorbed, you add the next one, stirring almost continuously so that the heat is distributed through the mixture and you achieve the rubbing away and dissolving of the starch around the outside of the rice, without breaking the grains.

At some point during this time, unless you are making a risotto just with grana cheese, you will add your principal ingredient: seafood, wild mushrooms, asparagus, etc. The exact point at which you add it varies according to how delicate or sturdy the ingredient is, but most keep their flavor better if they are put in around two-thirds of the way through cooking the rice, rather than added to the base.

When the rice is ready, i.e., tender but still al dente, you need to rest the risotto – just for I minute – off the heat, and without stirring, to bring the temperature down, ready to accept the addition of cold butter and cheese, at the final stage.

This last step is the mantecatura, the beating in of butter, cheese, and so on, which helps gives the modem risotto its unique consistency. Then you are ready to serve – and the sooner it is eaten, the better.

Risotto is something that I do for friends when they turn up unexpectedly – because what do you need for a basic risotto? Rice, stock, Parmesan … and from when you start adding the stock it should take only around 17 to 18 minutes for the rice to be cooked correctly (that is for 4 portions – the rule is the more rice you cook, the less time it takes, because the rice retains more heat). What I do with new chefs when we go through the risotto for the first time is set an alarm clock for 17 minutes, from that point, so that they can get a feel for the timing.

It is quite hard to get the texture right if you cook only a little risotto at a time, because the heat penetrates more strongly, so the rice absorbs the liquid too quickly. If you want to cook a risotto for one person, make enough for three, keep the rest to mold into a cake and bake it in the oven, or form it into little balls and deep-fry them to make arancini (see page 262).

On the other hand, trying to make too much risotto in one go is not a good thing either, because it is harder for the heat to circulate properly through a large quantity and the rice will not cook as evenly. Really, I think that around a kilo of rice (enough for 8 to 10 people) is as much as you can comfortably handle at home. Once, when I was at Zafferano, we made risotto for 280 people at a wedding, but we had 28 pans on the go.

I have seen chefs cook “risotto” for a lot of people in one huge pan, with all the stock added at once, without stirring. If the result tasted good, I would say, “Okay” – but this is not what a true risotto is about. You have to add your stock slowly and stir almost continuously to achieve the right texture at the end. The rule is one ladle of stock at a time, no more, until each addition of liquid is absorbed – no matter how much pressure a chef is under.

All that said, there is one old-style risotto that is magically made without stirring, called Risotto alla Pilota, after the guys who moved the rice around the fields using donkeys and couldn’t stop to stir their risotto at lunchtime. They would have minced meat or pancetta in some stock, then the rice went in in a stream through a cone made with paper, the heat was turned up gently, the lid put on, and it was left until the rice was cooked.

The beauty of risotto is that once you understand how it works, you can make it with anything you like, whatever is in season or you happen to have in the kitchen: seafood, asparagus, quail, mushrooms, peas, pumpkin (my granddad used to use leftover rabbit). At home, my son, Jack, loves the risotto we make with sausages and peas. It has become the dish that we do when we come back from vacation, because everything you need is either in the freezer or the pantry. As I have already mentioned, all that really varies is the time when you add this “garnish.”

Risotto can be a peasant dish, made with quite inexpensive ingredients, or it can be something quite sexy. And there are very few things you can’t add to it. What wouldn’t I put in a risotto? Mussels are possibly the only things. I hate mussels in a risotto; I don’t know why – I have had risotto where the mantecatura has been done with a little bit of mussel stock and lemon juice, which I have enjoyed – but for me, the texture of whole mussels in a risotto feels wrong.

Traditionally in Italy, a risotto is served alone, with the two famous Milanese exceptions of saffron risotto served with osso buco (veal stew) or cotolette alla Milanese (with veal cutlet), but when we used to cater for banquets, and especially weddings, at my uncle’s restaurant, La Cinzianella, we would make a centerpiece of veal and risotto. It was my job to do it. I used to take a saddle of veal and roast it lightly. While the meat was roasting, I would make a mushroom and truffle risotto, then put it in a food processor until the mixture became very sticky. When the meat was roasted I would take off the loin and cut it into thin slices; then, slice by slice, I would rebuild the shape of the saddle, using layer after layer of meat, with the gluey rice in between, then glaze it and put it back into the oven. When it came out, it looked and smelled beautiful, and, when you served it, it was full of magical flavors and creamy, sticky textures. I must have made that dish a hundred times during weekends at La Cinzianella, but I still love it.

Sometimes at Locanda, I also like to break free from tradition and serve risotto as an accompaniment; for example, we might serve a mushroom and black truffle risotto alongside roast quail. You can be as adventurous as you like, but it is hard to beat the classic recipe on page 214.

As beautiful as it tastes, I admit that a plain risotto is not a pretty thing, so in restaurants we need to make it appear more exciting. As a rule, I am not a great builder of elaborate dishes, but a chef must leave his mark. There is nothing worse than someone coming to your restaurant and afterward saying, “I don’t remember what I ate”; and part of what stays in your memory is the way a dish looks. So we might garnish a seafood risotto with langoustine tails or chargrilled crayfish, or a mushroom or pumpkin risotto with slices of those vegetables dried in the oven.

When we make risotto nero with calamari and its ink, we keep some squid back. Then, at the last minute, we heat some olive oil in a pan, put in the squid very briefly and take it off the heat the moment it turns opaque, so that we have a stark white piece of calamari to put on top of the black rice.

Sometimes, of course, you can get too carried away with trying to be artistic. Once when we were experimenting in the kitchen, I made a walnut and eggplant risotto and I decided to make some eggplant “chips” for a garnish. When I deep-fried the strips of eggplant, I thought they looked fantastic, but the other guys in the kitchen kept shaking their heads and saying they wouldn’t work, because there is so much water content in eggplants, they wouldn’t stay crisp. Naturally, the moment I put them on the hot risotto, they just drooped sadly – of course, everyone was standing behind me laughing. “Okay, guys, you were right.”

The easy rule to remember for risotto is to use 2 ¼ cups stock for each ½ cup of rice – that is enough for a hearty bowlful for one person at home. In the restaurant, we are more likely to use a little less rice, because we will usually serve a more delicate-looking portion with a more elaborate garnish.

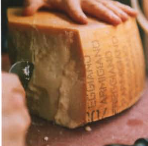

For the mantecatura, we use grana cheese (grana just means “grainy”), either Parmigiano Reggiano (see next page) or the famous cheese of my region of Lombardia: Grana Padano. Amazingly, though Parmesan is the name everyone knows around the world, Grana Padano is the biggest-selling Italian cheese at home and abroad. Both cheeses belong to the same family of grana cheeses, and look very similar. The difference is that the wheels of Grana Padano are stamped with the diamond mark of the consortium and the number of the dairy and date of production within a four-leaved clover. Grana Padano was first made 1,000 years ago, by Cistercian monks, and originated either in Lodi or Codogno in my region of Lombardia. Now it has its own DOP, but unlike Parmigiano-Reggiano, which can be made only in a very small area, the production stretches over a vast area of the Po Valley, from Piemonte and Lombardia to Veneto, as far as Trento, and production is more industrial in scope.

While the cheeses are made in the same way, there are important differences. The grana cows have a less specialized diet, and though both cheeses are made with milk from two milkings, for Grana Padano the two are simply mixed together, without the evening milk going through the Parmigiano process of separation into cream and skimmed milk first.

Grana Padano is aged less than Parmesan and tends to be softer, moister, subtler and lighter tasting. If I want to eat a piece of cheese with a pear, nothing else, then I would want some aged Parmesan, but in cooking, the two cheeses are almost interchangeable, though I can tell you the difference with my eyes closed. I use Parmesan when I want more salinity, and if I want something a little more sweet-tasting, creamy and clean I choose Grana Padano, for example in a quail or saffron risotto.

Incidentally, there is also a third important cheese in the family, which is also seeking its own DOP: Trentingrana, which at the moment is certified by the Grana Padano Association, but has the word Trentino stamped into its rind. It is made high up in Trento, with milk from two collections in the same way as Parmigiano Reggiano, and the farmers still take the cows even further into the mountains to graze in summer, keeping them inside only in winter. The seasonal difference is quite dramatic, and in summer, when the cows produce less milk, production is halved. The cheese is also eaten younger than Parmesan or Grana Padano.

“The king of Italian cheese”

Parmigiano-Reggiano, our wonderful cheese of the north, has the title of the king of Italian cheese, and it is – no question. You only have to put a few shavings of Parmesan over a dish and people say, “Oh how beautiful!” Not only does a wheel of Parmesan look magnificent but it is the biggest cheese in the world, weighing more than 30 kilograms (66 pounds) – and what other cheese enjoys such international celebrity?

Wherever Italians have settled in the world they have taken Parmesan with them. You could literally roll your Parmesan wheel down the street onto the boat and take it to Australia, because it traveled so well. Long before temperature-controlled trucks, Parmesan would still arrive at its destination in perfect condition. It took a little longer to get to Britain, though. When I first came to London, I was amazed to see that Parmesan came already grated, in little shakers. But the real thing is here now, so I am happy.

In Italy, the cheese is so important, they say that when your wife is pregnant, during the last few months you should give her Parmesan to eat, because it makes the milk for the baby more flavorsome. And in my region, when you eat Parmigiano-Reggiano, you never throw any of it away, so even the pieces of rind are collected, put into a bag, and then grilled for the kids to eat as a snack.

Italian food has been found to be high in umami, the fifth, “mouth-filling,” “savory” taste that comes from the amino acid glutamic acid, which is found naturally in ripe or cured, aged and fermented foods, like tomatoes, mushrooms, salami – but most of all Parmesan. Interestingly, the body also produces glutamate, especially in breast milk, so it seems that Italians for centuries have instinctively understood the “wow” factor of Parmesan, and attempted to enhance our appetite for it, even from infancy.

When the Florentine writer and poet Giovanni Boccaccio began his epic collection of medieval Italian tales, The Decameron, in 1348, he talked of a place called Bengodi where there was a mountain made entirely of grated Parmesan, and those who lived there did nothing but make gnocchi, or macaroni, and ravioli, which they used to roll down the mountain, dusting them in the cheese as they went, so the people passing by could pick them up and eat them. Can you imagine? What a fantastic place to live.

Parmesan began to be really well known in Italy somewhere between A.D. 800 and 900; and later, as usual, we Italians influenced French cooking when the Duchess of Parma married a grandson of Louis XIV in the seventeenth century and introduced the cheese to French kitchens. In 1951 they first gave the name Parmigiano-Reggiano to the cheese that is produced by a consortium of small artisanal cheese-makers in Emilia-Romagna; and since 1996 it has been designated as one of thirty DOP (Protected Designation of Origin) Italian cheeses. In order to carry the DOP mark, a cheese must be made in the provinces of Reggio Emilia and Parma (the original production areas), Modena, an area of Bologna on the left bank of the river Reno, or Mantova, on the right bank of the river Po.

There are around 600 of these small producers, called caselli. The word is one we also use for a toll that you pay when you enter a different zone on the highway. In Emilia-Romagna, though, it is used to refer to the fact that each producer makes best use of the different natural characteristics of his land to produce a cheese that is classically made, yet, like wine from a particular estate, it will also have its own individual character.

Each wheel of Parmigiano-Reggiano carries its own ID, printed on the rind, showing the code number of the dairy, the mark of the consortium (which guarantees strict standards) and then the month and year of production, so you can track your cheese all the way back to the beginning – who was the farmer? What was the milk like at that time of year? Everything can be found out.

How do you describe a good Parmesan? Well, the slightly oily rind can range in color from golden to brown and should be around ¼ inch thick. Inside, the color of the cheese can also vary from pale ivory to golden straw, but the flavor should always be quite intense, rich and slightly salty, and the texture should be fine-grained and crumbly – slightly moist when the cheese is young and drier when it is aged.

In Reggio-Emilia, where producers are recognized by code numbers under 1,000, and where many believe the finest, most classic cheese is made, you still find very small cheese makers, producing only 8 to 12 wheels of cheese a day, who still take their cows on the traditional climb up through the hills each summer so that they can graze on fresh mountain grasses and herbs (in winter they would eat hay and stay indoors in barns). We call this cheese Parmigiano di montagna.

However, many producers are now following a new feeding system called the piatto unico, a sort of “big dish” in which fresh grass and hay are balanced with vitamins, proteins, water, and so on. And instead of grazing outside in summer, most cows spend more time lazing in modern, roomy cowsheds, as the farmers believe that this gentler, more sedentary lifestyle produces richer, creamier milk, though the cheese still retains its seasonal nuances: drier and more crumbly in summer; richer and heavier in winter.

The cows are milked twice a day, in the morning and evening, and each batch of cheese is started off with the milk from the evening’s milking. It is put into wide, shallow troughs, and the cream is allowed to rise to the surface. The next morning the cream is taken off and the skimmed milk that is left is mixed with the new whole milk from the morning’s milking. Then it is put into vats and in order to start the fermenting process it is inoculated with enzymes, which come from the soured whey left over from making the previous batch of cheese.

Next, the milk is heated and calves’ rennet is added. Once it has coagulated, the curd is cut into granules (which give the cheese its grainy texture), then heated again and finally transferred to molds in which it is left to drain for two or three days. After that, the cheese goes into a bath of brine for 24 more days to give it its saltiness.

Then the maturing process begins in huge cellars, with the enormous wheels of cheese stacked on racks high up into the ceiling for at least 12 months (when the cheese is known as nuovo), but it can be much longer, according to the quality of each individual cheese. They say that the prime age for Parmesan is at 24 months, when it is known as vecchio and is believed to be at the peak of its organoleptic properties (i.e., its appearance, smell, taste, feel, and so on). This is the age of the Parmesan that we use at Locanda for virtually everything in the kitchen. After that, as it matures, its flavors become more sophisticated, but it loses a lot of humidity and the texture becomes drier. Twenty-four months is considered a good age for eating the cheese just as it is (when it is over two years old, it is known as stravecchio), but you can keep Parmesan for up to three years, and very exceptionally four.

In Italy, especially in the countryside, where they have more space, a restaurant might buy six wheels of Parmesan at a time, so it can have a selection of cheeses of different ages. And it will serve the most special stravecchio at the end of the meal, with great ceremony at your table, using a special knife to scoop out the cheese from the center of the enormous wheel.

In London, though, the market for aged Parmesan is very small, and many cheese shops and restaurants think it is too expensive to bring in – but I don’t care about the price because a fantastic three-year-old Parmigiano-Reggiano is one of the most beautiful things to have after lunch or dinner. We serve ours from the cheese trolley, with a little chutney, or some sliced pears, or just with a touch of 50-year-old balsamic vinegar – for me, these two ingredients, together with a wonderful prosciutto, just sum up the whole idea of what Emilia-Romagna is about.

Made with a base of onions and chicken or vegetable stock, this is finished with Parmesan or Grana Padano, and butter. In our house, as in most houses in the region, grana was the cheese we used most in cooking, while Parmesan was kept for the table. It is the most straightforward risotto of all – the one that everyone in Italy cooks and that you are given as a child when you are sick. First some tips:

Chop the onions as finely as you can (the size of grains of rice): this is because you don’t want the onion to be obvious in the finished risotto, and if you have large pieces, they will not cook through properly.

Grate the grana finely so it is quickly absorbed at the end of the process.

Make sure that your butter is very cold. Cut it into small, even-sized dice before you start cooking and put it into the fridge until you are ready to use it. That way it won’t melt too quickly and it will emulsify rather than split the risotto.

Remember, the more rice you cook, the more heat it will retain, so it will take less time to cook.

10 cups good chicken stock (see page 264)

3 ½ tablespoons butter

1 onion, chopped very, very fine (see tip above)

2 cups superfino carnaroli rice

½ cup dry white wine

salt and pepper

For the mantecatura:

about 5 tablespoons cold butter, cut into small cubes

about 1 cup finely grated

Grana Padano or Parmesan

Put the stock into a pan, bring it to a boil and then reduce the heat so that it is barely simmering.

Making the soffritto

Put a heavy-bottomed pan on the heat next to the one containing the hot stock, and put in the butter to melt. The choice of pan for risotto is important, as a heavy base will distribute heat evenly, preventing burning.

As the butter is melting, add the onion and cook very slowly for about 5 minutes, so that it softens and becomes translucent, losing the pungent onion flavor, but doesn’t brown – otherwise it might add some burned flavor to the risotto and could also spoil its appearance with brown flecks.

I don’t recommend that you add any salt at this point, because the stock that you will shortly be adding will reduce down, concentrating its flavor and saltiness. You will also be adding some salty grana at the end, so it is best to wait until all these flavors have been absorbed and then decide at the end whether you need any seasoning or not.

The tostatura – “toasting” the rice

Turn up the heat to medium, add the rice and stir, using a wooden spatula, until the grains are well covered in butter and onions, and heated through – again with no color. It is important to get the grains up to a hot temperature before adding the wine.

Add the wine and let it reduce and evaporate, continuing to stir, until the wine has virtually disappeared and the mixture is almost dry – that way you will lose the alcohol and tannins. If you don’t let it reduce enough you will get a slightly bitter flavor of wine in the risotto.

Adding the stock

From this point to the end of the cooking, for this quantity of risotto, should take about 17 to 18 minutes (a minute or so less if you are doubling the quantity). Start to add the stock a ladleful at a time (each addition should be just enough to cover, but not drown, the rice), stirring and scraping the base and sides of the pan with your wooden spoon. Let each ladleful be almost absorbed before adding the next.

The idea is to keep the consistency runny at all times, never letting it dry out, and to keep the rice moving so that it cooks evenly (the base of the pan will obviously be the hottest place, and the grains that are there will cook quicker than the rest, unless you keep stirring them around). You will see the rice beginning to swell and become more shiny and translucent as the outer layer gradually releases its starch, beginning to bind the mixture together and make it creamy.

Keep the risotto bubbling steadily all the while as you continue adding stock, stirring and letting it absorb, before adding more again.

After about 15 minutes of doing this, start to test the rice. A word of warning: let it cool before you taste, as risotto retains the heat dramatically, like polenta, and you will burn your mouth if you don’t wait for a moment. The rice is ready when it is plump and tender, but the center of the grain still has a slight firmness to the bite.

When you feel you are almost there, reduce the amount of stock you are adding, so that when the rice is ready, the consistency is not too runny but nice and moist, ready to absorb the butter and cheese at the next stage and loosen up some more. If it is too soupy at this point, once you add these ingredients the finished risotto will be sloppy, whereas if it is not quite wet enough, you can always rescue the situation by beating in a little extra hot stock to loosen it up at the end, after the mantecatura.

Take the pan off the heat and let the risotto rest for a minute without stirring. This slight cooling is important because you are about to add butter and cheese, and if you add these ingredients to piping-hot risotto, they will melt too quickly and the risotto may split. You see this sometimes in restaurants, where the grains of rice, instead of clinging together, seem to stick out, each surrounded by a little pool of oily liquid.

The mantecatura

Quickly beat in the cold butter cubes, then beat in the cheese, getting your whole body behind it, moving your beating hand as fast as you can, and shaking the pan with the other. You should hear a satisfying thwock, thwock sound as you work the ingredients in. The result should be a risotto that is creamy, rich and emulsified.

At this point, taste for seasoning and, if you like, add a grind of salt and pepper. Remember, though, that if your stock is strongly flavored, and once you have added the salty cheese, the risotto may not need any seasoning at all.

Serve the risotto as quickly as you can, as it will carry on cooking for a few minutes even as you transfer it to your serving bowls (shallow ones are best), and you want to enjoy it while it is at its creamiest.

If you have achieved the perfect consistency (all’onda), when you tilt the bowls the risotto should ripple like the waves of the sea.

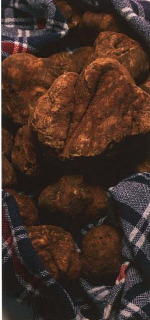

“A smell of people”

Ever since I was little, I have thought of white truffles as exciting and mysterious, and of course expensive. Our family wasn’t rich, but every year we went with my granddad to the fair at Alba to buy the truffles and bring them home so my grandmother could cook a special meal from them – we went just for us, not even to buy truffles for the restaurant. It was an annual tradition: and I think a lot of families did the same thing. It was a fantastic place for a young boy to be. The big square was full of stalls, where the trifolau (truffle hunters) set out their weighing scales and their truffles, mysteriously wrapped up in cloths. You had to haggle with them and do deals over the price of the truffles, and often they would keep their biggest and most valuable ones hidden away, unveiling them with great ceremony only when they recognized a buyer with serious money to spend.

Now, during the short season (from the end of September to early December), we have customers who come in to the restaurant to eat truffles every day. I have always thought, though, that you shouldn’t eat them twenty times, just two or three times in a year, because every time you taste a truffle it should be a special thing, and there should be plenty of it; a big, generous helping. Alexandre Dumas, who was a great lover of truffles (though, being French, he favored the black truffle of Périgord), wrote, “When I eat truffles, I become livelier, happier, I feel refreshed. I feel inside me, especially in my veins, a soft voluptuous heat that quickly reaches my head. My ideas are clearer and easier.” He also believed that the first requirement for something to be a luxury is that you are not mean with it; it must be celebrated in abundance. In other words, true luxury is not snobbish, but three mean little slivers of truffle, now that is snobbish. I think that is exactly right.

The white truffle from the area around the ancient city of Alba Pompeia in Piemonte has become like the blue-and-white pottery of Delft in Holland: something famous and symbolic not only of its own region but of the entire country. The local name for it is the trifola, though its scientific name is Tuber magnatum pico, and it has been enthroned in our society since the days when the custom was that the biggest truffle would be presented to the King of Italy. Now we have no more kings, but the tradition in Alba has still been to present important visitors to the region, such as Marilyn Monroe, Mikhail Gorbachev or Gianni Agnelli, the president of Fiat, with a special truffle. The record so far was the one weighing 2 kilos and 520 grams (5 ½ pounds), which was given to President Truman in 1954.

The first time someone tastes a truffle, they often find it quite disappointing, even off-putting, because usually they have heard so much about them and they expect so much. Sometimes people say to me, “Oh, they smell of feet. Horrible!” It hurts me to hear it, but I understand. If life could be described in a smell, then it is the smell of truffles. They smell of people and sweat. They just remind me so much of human beings; that is why I love them. Also, I think, as you get older, you appreciate truffles more, I don’t know why.

Other people have described truffles a bit more delicately than I do, as the perfect marriage between the flavors of garlic and Parmesan, but it is the smell that is released when a truffle is at body temperature, rather than the flavor, that is so powerful; it fills your nose and stays there for a long time. Scientists say that there is a volatile alcohol in truffles that has a very strong musky character related to testosterone, so maybe that is another reason for their attraction. Remember, though, that a truffle is at the peak of its powers for only around fifteen days – after that it begins dramatically to lose its aroma and flavor.

Because the truffle is such a unique thing, it is traditionally used very simply – shaved over a risotto made with grana cheese, or on top of pasta, beef carpaccio or eggs – so no other flavor can try to compete with it. In Piemontese restaurants during the season, they serve the traditional dish of fonduta, which was once the meal of local farmers but is now considered a luxury. Fontina cheese from Valle d’Aosta is heated with milk, egg yolks and butter until it is creamy, then some white truffle is shaved over the top, and you eat it with slices of toasted bread to dip in it.

The truffle hunt, like the mushroom hunt, is an exciting thing. For many people, especially city folk, it feels too harsh to go hunting for game – to go out with a gun and hack down an animal or bird and see it die – even fishing is something difficult for some people to accept. But if you go out with the dogs hunting for truffles you have all the same sensations: the waiting, searching, chasing, hiding from other truffle hunters – but without the pain. If you see a truffle, the joy and fulfillment is the same as coming across a deer, but there are no losers; no one has to give their blood or their life. Of course, it is a bit depressing when you spend five hours looking, and you find nothing. But you can always find a good restaurant nearby and have a portion of truffles to eat anyway.

In the old days, they thought that truffles were the result of lightning bolts hitting the ground close to trees, because they were such incredible, in explicable treasures: and if anyone could find a way of cultivating white truffles they would make a fortune. Being such a profitable business – white truffles from Alba have fetched $125,000 for 1.2 kilos (2 ⅔ pounds) – it has been studied inside out. They say the last king of Italy, Umberto II, paid people to try to grow truffles, but they just took his money and kept spinning him stories, because nobody has ever come up with the solution.

Truffles are a wild fungus and for them to grow the ground must have certain properties. (What kind of soil the truffles grow in also decides their shape. Smooth truffles grow in soft soil; the lumpy, knotty truffles come from soil that is more compact.) Most of all, though, they need trees, because the way they grow is to absorb water, mineral salts and fibers from the soil, through the roots of the trees. You can tell whether a truffle has grown close to oak, hazelnut, poplar, lime, willow or cherry – the trees the truffle favors – because each tree gives the fungus a slightly different character. (They say the harder the tree, for example oak, the more intense the smell of the truffle; so those that grow close to lime trees are lighter in aroma.) Really, the difference is incredible. Which is why, when we buy truffles, we examine them one by one, because you can have three collected by the same guy in Italy from the same place, yet one will have grown closer to a particular tree than the other, and each will be completely different: one dark, one light, one very, very pungent, another much softer.

People have tried inoculating the exposed roots of trees with spores from the truffles to try to grow more, with some success for black truffles, but not with the white truffle, which keeps its sense of mystery – where it grows has also to do with the microclimate and the phases of the moon. You can’t be in Bournemouth and say, “Okay, I’m going to grow truffles,” because if you look at some of the other places where truffles are historically found, like Albania, Romania or Yugoslavia, they are on the same parallel as Alba, with similar microclimates. In Italy, on that same parallel, all along the Appennino mountain range to Acqualagna in the Marche region, you can find fantastic white truffles – but because they don’t come from Alba, people think they are not as good and they sell for a third of the price. There is nothing wrong with eastern European truffles, either, they just don’t grow as big as the ones from Alba, or have the same mystique.

In the last 50 years, the Piemonte region has also maximized the production of its Barolo and Nebbiolo wines – and some of the original truffle ground is being given up to make space for the vines. So you might have a stretch of wood, then a space, then more wood, which affects the cross-insemination of the truffle spores by animals. So the quantity of truffles (both black and white) has come down, but the demand and the prices have gone up, which is a big problem for the truffle traders of Alba. Every year millions of people arrive from around the world for the truffle fairs, and if there are not enough truffles, the trifolau don’t make their money.

So, if there are not enough truffles, what else can you do but bring some in from somewhere else? In one of the biggest stories to come out of Alba in recent years, a family with a 200-year history of dealing in truffles was found with a cache of 24 tons of black truffles from China.

Tartufi neri

If I were French, I might get more excited about black truffles. If you ask someone from Périgord what are the best truffles in the world. I doubt if he would say the white ones from Alba. Of course, I love black truffles too, but they don’t have the intensity of flavor and smell of the white ones.

While white truffles smell of all human life, black truffles remind me of damp cellars. However, they are still in season when the white ones are finished (they begin in November and go on until March) and they come again in summer, though the winter ones are usually of a better quality.

Our customers love the magic of white truffles so much that I wouldn’t serve black truffles over risotto or pasta, but at home I might. The exception is gnocchi, because black truffles have a particular earthy affinity with potatoes – they seem to bring out the best in each other – and because they are not as crazily expensive as the white ones, they are a way of giving a simple dish a sense of luxury.

I love truffles, but I hate all the by-products – I would never buy truffles in brine, as they don’t have the same flavor, and the thing I detest most is commercial truffle oil, which some people drizzle over everything. It invariably contains a chemical flavoring that messes up your taste buds and repeats on you. Fresh truffles begin to lose their intensity of scent and flavor quite quickly, so they are no good for oil that must be kept for months, which is why most manufacturers resort to artificial means.

At Locanda, we make our own truffle oil (though we don’t use it for risotto), which has to be used within two or three days or it will lose its intensity. In the restaurant, it is inevitable that we end up with lots of small pieces of truffle. When someone pays a lot of money for white truffle to be grated over their pasta or risotto, you can’t just bring a little piece to the table, it has to be a whole (or at least a half) truffle. So the pieces that are left over each day are chopped, crushed and then put into oil in a bottle, which we keep in a bath of warm water, so that the aroma and flavor stay powerful.

If, when you go to buy your truffles, you are allowed to take off a little skin and look at the inside, the truffle should be light to dark brown. If it is white or off-white, it is either not mature enough or it has been found in wet soil and taken in so much water that it has turned white. If you were to keep it in the fridge on a sheet of paper, it would mature a little more – but remember that everything else in the fridge might also smell of truffles, and every day you keep them, they lose moisture and weight.

You can buy truffles already cleaned, but if you need to clean them yourself, put some water into a bowl with an equal quantity of white wine, dip a small, soft brush into it and brush the truffle very lightly, then pat dry.

Make the risotto as for Risotto alla lodigiana (see page 214). You need a white truffle and a teaspoon of white truffle butter, which you can buy at Italian delicatessens. At the final stage of the risotto – the mantecatura – add the truffle butter along with the grana. Serve the risotto in bowls and then shave the cleaned white truffle over it at the table with great ceremony. (See previous page for how to clean a truffle.) For the ultimate truffle risotto, put a truffle into your jar of rice for at least 24 hours before you want to make it, so that its wonderful aroma can infuse the rice.

Saffron has been valued as a spice and a dye since Greek and Roman times. According to one legend, we have to thank the Greek god Hermes, the winged messenger, for saffron (he was also in charge of looking after olive trees, so he was a very useful god). One story is that he was throwing his discus when he hit his friend Crocus, who fell down dead on top of some flowers. To honor him, Hermes turned the stigmas of the flowers scarlet, and it is the stigmas of the species Crocus sativus that give us saffron.

Although saffron was used in Roman times, it may also have been introduced to my region of Lombardia by the Spanish when they invaded in the sixteenth century. And the Spanish may have been introduced to it through trade with the Arabs, who gave saffron its name of zaffer, the root of the Italian zafferano.

One of the reasons that saffron is considered so precious, and is so expensive, is that it takes around 50,000 flowers, which must be harvested by hand, and the stigmas dried, to give every pound of saffron. I spent three days in the village of La Mancha in Spain at harvesttime, and it was a beautiful sight: suddenly there were mountains of flowers everywhere – you wanted to jump into them. Seeing the pillows of flowers, and knowing what care and effort went into producing the spice was another reason why I called my first restaurant Zafferano.

However, it is quite fitting that Hermes was also supposed to be the god of thieves and commerce, because the high prices you can ask for saffron have often meant that people have tried to cheat, by mixing other spices into powdered saffron, like the cheaper turmeric, or safflower, which will add color but no flavor; or even by bulking up saffron threads with the dyed fibers of beet or pomegranate.

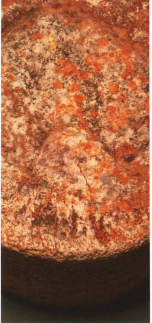

The saffron risotto my grandmother used to cook is also known as risotto Milanese, and is famous in Lombardia. It is the only risotto of my region that is traditionally served alongside meat – with osso buco or cotolette alla Milanese – probably it was designed as a quick lunch for city businesspeople or factory workers who had no time to have first the risotto and then the meat course.

I don’t know what it is about saffron and rice that make them work so well together, but they are natural partners that travel together around the world, from paella to risotto to saffron rice in Morocco, Iran and India.

This risotto follows the recipe for Risotto alla lodigiana, but is made richer by putting in some saffron threads with the first addition of stock – threads feel a little more luxurious, and keep better than saffron powder, which was all my grandmother had to use. Buy the best quality you can find – long threads are often an indication of good saffron.

Traditionally you would also add veal marrow to Risotto allo zafferano, which makes it very rich, but if you prefer not to use marrowbone, then you can make it without, as in the recipe that follows.

If you do want to make the risotto with marrowbone, for four people use five marrowbones. Rinse them first in cold running water for about an hour, then push out the marrow from inside. Preheat the oven to 375°F. Put the marrow from one of the bones in the risotto pan with the butter at the beginning of cooking, and smash it up with a fork, before adding the onions.

Lay the rest of the marrow on a baking tray and sprinkle it with a mixture of 4 tablespoons of bread crumbs and 4 tablespoons of grated Parmesan and, while the risotto is cooking on top of the stove, put the tray into the preheated oven for 4 to 5 minutes, until the mixture is golden on top. Drain off any excess fat from the marrow and then slice it and serve on top of the finished risotto.

Note: When we make the chicken stock for this risotto, we add a little tomato paste to the chicken bones when they are roasting (see page 264). This gives the stock a rosy color and will make the finished risotto look more vivid. Italians wouldn’t normally do this – they would just boil up a whole chicken or a carcass, so they might just add a teaspoon of tomato passata to the risotto as they start to add the hot stock.

Bring your pot of stock to a boil next to where you are going to make your risotto, then turn down the heat to a bare simmer.

Melt the butter in a heavy-bottomed pan, and add the chopped onion. Cook gently until softened but not colored (about 5 minutes).

Add the rice and stir to coat it in the butter and “toast” the grains. Make sure they are all warm, then add the wine. Let it evaporate completely until the onion and rice are dry, then add the saffron. Start to add the stock, a ladleful or two at a time, stirring and scraping the rice in the pan as you do so. When each addition of stock has almost all evaporated, add the next ladleful.

Carry on cooking for about 15 to 17 minutes, adding stock continuously (if you like, you can add a teaspoon of tomato passata to bring up the color). After about 12 to 14 minutes, slow down the addition of stock, so that the rice doesn’t become too wet and soupy, otherwise when you add the butter and Parmesan at the end, it will become sloppy. The risotto is ready when the grains are soft but still al dente. Turn down the heat and allow the risotto to rest for a minute.

For the mantecatura, with a wooden spoon, vigorously beat in the cold butter cubes and finally the cheese, making sure you shake the pan energetically at the same time as you beat. Season to taste and serve.

10 cups good chicken stock (see page 264)

3 ½ tablespoons butter

1 onion, chopped very, very finely

2 cups superfino carnaroli rice

½ cup dry white wine

about 40 good-quality saffron threads (look for long ones)

1 teaspoon tomato passata (optional, see note on page 226)

For the mantecatura:

about 5 tablespoons cold butter, cut into small cubes

about 1 cup finely grated Grana Padano or Parmesan

salt and pepper

For this risotto, we use every part of the asparagus – the tender spears go into the risotto itself and the peelings and woody stems are made into the simple stock. There is also more onion than usual because, as well as using it for the base of the risotto, we cook the asparagus stalks separately with onion.

12 asparagus spears

7 tablespoons butter

2 onions, chopped very, very fine

2 cups vialone nano rice

½ cup dry white wine

salt and pepper

For the stock:

3 tablespoons olive oil

4 onions, diced

For the mantecatura:

about 5 tablespoons cold butter, cut into small cubes

about 1 cup finely grated Parmesan

First prepare the asparagus: wash, then peel each spear below the tip and keep the peelings. Cut off the tips, then trim off the woody part of the stem (keep these back also and crush lightly with the back of a kitchen knife). You should now have three different mounds of asparagus: the tips, the tender spears, and the crushed woody ends and peelings.

To make the stock, heat the olive oil in a deep pan, add the diced onions and sweat them until soft but not colored. Add the asparagus trimmings and the crushed woody stems, cover (to keep in the moisture) and cook for another 5 to 6 minutes.

Cover the mixture completely with about 10 cups cold water, bring to a boil, then turn the heat down and simmer for about 20 minutes.

Remove from the heat and put through a fine sieve, squeezing and pressing the vegetables, to get all the flavor into the stock. Reserve for later.

While the stock is cooking, dice the asparagus spears, reserving the tips.

Heat 3 ½ tablespoons of the butter in a pan, add one of the chopped onions and cook gently until soft but not colored. Add the diced asparagus, cover and cook for 7 to 8 minutes.

Put 2 tablespoons of the cooked asparagus into a food processor and pulse into a puree, then mix in the rest of the cooked asparagus. Season and keep to one side.

Now you are ready to start the risotto. Return the stock to the heat close to where you are going to make your risotto. Bring it to a boil, then turn the heat down to a bare simmer.

Melt the remaining butter in a heavy-bottomed pan and add the other chopped onion. Cook gently until softened but not colored (about 5 minutes). Add the rice and stir around to coat in the butter and “toast” the grains. Make sure all the grains are warm, then add the wine. Let the wine evaporate completely until the onion and rice are dry.

Start to add the stock, one or two ladlefuls at a time, stirring and scraping the rice in the pan as you do so. When each addition of stock has almost all evaporated, add the next ladleful.

After about 10 minutes, add the reserved asparagus mixture and bring the risotto back up to temperature. Carry on cooking for another 5 to 6 minutes until the grains are soft, but still al dente, adding more stock as necessary. Remember, you don’t want the risotto to be soupy when you add the butter and Parmesan, or it will become sloppy.

Blanch the reserved asparagus tips for about a minute in the stock, remove with a slotted spoon, set aside and season.

When the risotto is ready, turn down the heat and allow the risotto to rest for a minute; then, for the mantecatura, using a wooden spoon, vigorously beat in the cold butter cubes and finally the Parmesan, making sure you shake the pan energetically at the same time as you beat. Season to taste and garnish with the asparagus tips.

This is a spring risotto – for when the nettles are growing everywhere. Food for free. Just remember to handle the nettles with gloves, or avoid touching the stalks, which are the part with the sting. In the restaurant, we garnish this risotto with deep-fried nettle leaves.

2 handfuls of young nettle leaves

10 cups good vegetable stock (see page 268)

3 ½ tablespoons butter

1 onion, chopped very, very fine

2 cups vialone nano rice

½ cup dry white wine

salt and pepper

For the mantecatura:

about 5 tablespoons cold butter, cut into small cubes

about 1 cup finely grated Parmesan

Blanch the nettles in boiling salted water for 30 seconds, drain and put into a food processor. Pulse to a puree, adding a little water if the mixture isn’t moist enough.

Bring the pot of stock to a boil close to where you are going to make the risotto, then turn the heat down to a bare simmer.

Melt the butter in a heavy-bottomed pan, and add the chopped onion. Cook gently until softened but not colored (about 5 minutes).

Add the rice and stir it around to coat it in the butter and “toast” the grains. Make sure all the grains are warm, then add the wine. Let the wine evaporate completely until the onion and rice are dry.

Start to add the stock, a ladleful or two at a time, stirring and scraping the rice in the pan as you do so. When each addition of stock has almost evaporated, add the next ladleful.

Carry on cooking for about 15 to 17 minutes, adding the stock continuously in this way. After about 10 minutes, add the nettle puree and bring the risotto back up to temperature. Carry on cooking for another 5 to 6 minutes until the rice grains are soft but still al dente, adding more stock as necessary. The risotto shouldn’t be too soupy when you add the butter and Parmesan at the end, or it will become sloppy. The risotto is ready when the grains are soft but still al dente.

Turn down the heat, to allow the risotto to rest for a minute; then, for the mantecatura, using a wooden spoon, vigorously beat in the cold butter cubes and finally the Parmesan, making sure you shake the pan energetically at the same time as you beat. Season to taste and serve.

“You never heard a mushroom scream”

For me it is very romantic when the first porcini come into the kitchen. Porcini herald the start of autumn, that season that is so wistful but also so dramatic and operatic in its colors and its mood. In the city, you get so little sense of the influence of the seasons. The weather turns cold so you put on a hat and a scarf, or it gets hot so you wear a T-shirt, and that’s it. In the country, the shift of seasons means so much more. In spring and summer, even when you are eating fish and grilling vegetables outside, you are already thinking ahead to preserving vegetables for the autumn and winter; when the tomatoes are plentiful, you make big jars of passata for later. Autumn signals the beginning of the season of warming stews and risotti; it is a time when you smell the fires being lit; a less busy season, when you go through a kind of quietness in preparation for the snow and ice of winter. Above all, it is the time when you get the best food for nothing. Besides the wild mushrooms (funghi), you have chestnuts, and game … but nothing represents that generous idea of free food for everyone more than porcini.

Growing up in Lombardia, you have a kind of mythological admiration for the mountain people and shepherds, who are completely at ease and in tune with nature and always know where to find wild food. There is something a little mystical about these guys. They usually don’t talk too much and often seem a little weird, but there is a magic in the way they always know where to find the biggest mushrooms or the best fish. There was a man called Mauro, a woodcutter, who lived near our village, who would check by the moon which were the best days for mushrooms and then he would be up and out at four?’ clock in the morning. He knew that the mushrooms that grew near the pine trees, underneath all the needles that the tree had shed, would have dark caps and be white underneath, and the ones that grew near the chestnuts would be solid, with dark brown caps and slightly more yellow underneath. He knew how the flavor would depend on the water and mineral content of the ground – the ones near pine, because they had less water, would have a very concentrated flavor: he knew everything … Sometimes he would let us kids go out with him, which was such a privilege. At ten years old, I wanted to be a man of the mountains, like Mauro.

The joy of finding wild mushrooms, as with finding truffles, is similar to the excitement you feel when you hunt or fish, but without the suffering of any creature. You never heard a mushroom scream. Antonio Carluccio told me that after the former Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who is passionate about mushrooms, ate in his restaurant, he sent him a copy of his book. Gorbachev wrote back to thank him, and he talked about “the quiet hunt,” which is the way the Russians describe searching for mushrooms. I love that description.

No one I know ever got rich picking mushrooms, but you could make some kind of living selling them. Near my house, in the season, you would come across women or young girls sitting by the side of the road with a few boxes of porcini, picked that morning – and if you were driving it was fantastic to put them in the car and travel with that beautiful smell wrapping around you. It’s not something you can easily describe; let’s just say it is a benchmark smell – sweet, strong, distinctive, like woodland.

The name porcini comes from porcinus, which means “like a pig” (porcus), perhaps because the mushrooms are fat, like little pigs, though the official Latin name is Boletus edulis. In England, porcini were known as penny buns, but these days most people know them by their French name, ceps. Now in northern Italy, like everywhere, they eat lots of different varieties of wild mushroom, and in our kitchen we often serve a mixture, but for me, though other mushrooms can be beautiful, they don’t capture that flavor of the wild in quite the same way. When I was young, the only mushrooms anyone hunted for seriously were porcini, though sometimes we would take the tiny chiodini, which taste slightly bitter, like chanterelles. (Chiodo is the word for nail, and they were shaped like very tiny nails.) My grandmother used to preserve them under vinegar to serve with salami.

If we saw the Milanese arriving from the city to pick field mushrooms, we laughed because none of us locals ever ate them. There were morels too, but we had no interest in them either. I remember when I went to Paris, the chefs in the kitchens became so excited when the first morels of the season arrived, and we sold diem in the restaurant for $70 a portion. I looked at them, and thought, “I have been kicking those around the woods for 20 years.”

Now the people come from the city to the woods around Corgeno for the porcini too. In the season, the moment the weekend arrives you see the cars with the Milano license plates parked all over the verges and people swarming all over the mountains. Sometimes things can get a bit crazy – it has been known for people to come back to their car and find it gone, or the tires punctured, because they were on someone else’s “patch.” I don’t like the idea of that, because the food of nature is for everybody, and that is what I love about it. The mushrooms are there to be picked – as long as people respect the woods. You mustn’t use rakes or instruments, just the naked eye. Although you must be careful when you put your hand down because there are sometimes small vipers in the undergrowth.

That’s not to say it isn’t a competitive business, just that the local people have a quieter way of doing things. Fishermen will always say: “I caught a fish this big!” and every time they tell the story the fish gets bigger, but the people who hunt mushrooms are completely different. You have to be more secretive. Because the mushroom spores develop underground, porcini usually grow in families. Occasionally it is possible to find just one mushroom, but it is unusual – if you spot one, there will usually be more. As kids, we knew the rule that you never scream out if you see a porcino. You must look around to see that no one else is there, before you say, “I’ve got one,” otherwise someone will come and find the mushrooms next to yours.

Almost every day during the season, my granddad took my brother, Roberto, and me up into the woods to look for mushrooms and he always brought two baskets (you must always use woven baskets when you pick mushrooms, so that they are kept nice and airy and the spores can fall through, back to the earth to reseed). He would put just a few mushrooms into one of the baskets, and the other one would be full. Then, if he saw someone coming, he would hide the full one and say, “Naah, nothing much around here, really bad; look, this is all I have …”

The biggest mushroom we ever found was massive – about 2 pounds. Of course, Roberto and I argued all the way home saying, “I found it!,” “No, you didn’t – I saw it first!,” with my granddad telling us, “Okay, okay! Just don’t break the mushroom!” We came hurtling down the mountain and started to shout to my grandmother, “Look at this mushroom!” We got to the road by our house and, I don’t remember whose fault it was, but in our huge excitement we fell over each other and this fantastic porcino broke into a hundred pieces.

Now I love to go mushroom hunting with my own kids, just roaming around – such a healthy pastime – and in these days when we are not used to getting anything for nothing, it is good for them to see what nature can offer. Of course, the most important thing is to remind everybody that you don’t eat anything if you don’t know what it is. There was a story that used to be told in our village about a man who lived not far away from us, who was said to have killed three of his wives with poisonous mushrooms. Whenever anybody came into the bar next to our hotel and said he had had a fight with his wife, the joke used to be “Mushrooms for dinner tonight!”

Mushrooms grow all over Italy, right down to Sicilia, but their flavor is determined by the different types of woodland and the local climate. As always in Italian cooking, recipes grow up around produce that is grown or raised in the same region. So at home in Corgeno we mostly had mushrooms in risotto, or with pasta, though sometimes my grandmother made a beef stew with red wine and mushrooms, which had a flavor I can still taste. We used to eat it with polenta. Polenta, rice, pasta – all these starchy ingredients seem to go really well with the flavor and texture of porcini. One of my favorite dishes that we serve in the restaurant is new potato ravioli with wild mushroom sauce – fantastic.

Sometimes I see mushrooms being served as a side dish for a main course, which always seems strange to me. In Italy, if you have mushrooms, they are a main part of a meal or the antipasto – not an accessory.

For me, one of the best things about porcini is their slightly slimy texture, which amazes me every time – it seems to be a completely new experience for the mouth. How many foods, except for oysters, have that strange texture, and yet eating them is a pleasant experience? Smell and texture, these are what make porcini special. In a strange way, their distinctive nutty flavor, fantastic though it is, is almost secondary.

I always think that when you cook porcini, it is best to keep the flavors really simple – exaggerate the taste of the mushroom, rather than complicate things with too many other ingredients – and be careful not to overseason them, especially with salt, because they are very receptive to flavors and will take in anything you offer them.

Where I come from in Italy, you would never mix sea and mountain, so I don’t like to eat mushrooms with fish – mushrooms, cheese and fish are three things that I don’t think go well together. However, if you travel not too far away, to Liguria, you find a lot of mushrooms growing up in the mountains close to the sea, and there you do find mari e monti (sea and mountain) recipes; and they are also becoming more common in contemporary Italian cooking.

In the north, we cook porcini simply in butter with parsley and garlic and some white wine. Garlic is a great enhancer of the flavor of porcini. I also like to put a little chile pepper with them, or a squeeze of lemon juice, and I prefer to cook mushrooms in butter rather than oil, because, again, I think it brings out their flavor, whereas if you use a flavorful oil, especially a piquant Tuscan one, that is all you taste.

In the south, where tomatoes are so plentiful, they cook mushrooms with tomatoes, which is something we would never do in the north, but, if it is done well, the acidity from the tomato can really help bring out the sweetness of the mushrooms.

I must admit that one of the most beautiful, really simple plates of pasta and mushrooms I ever had was in Val Varaita, in the north of Italy, made for me by some people from the south. They just cooked the mushrooms in a little oil with some wine, let it reduce, then chopped in some wonderful fresh tomatoes, covered the pan and let everything simmer for about 10 to 20 minutes to reduce the sauce some more, then tossed some tagliatelle through it, and it was fantastic.

Until I left Italy, I never saw mushrooms cooked harshly in a sauté pan, so you get that crisp brown caramelized outside that chefs in France and England like. In Italy, we always cooked the porcini gently in the butter and garlic, letting the mushrooms dissolve,’ without browning. Porcini don’t contain as much water as we think; they have quite a lot of fiber and cooking slowly like this really accentuates the flavor. When I worked for Corrado Sironi, the Risotto King, we used to cook big potfuls of them, with a piece of lemon peel put in as well. In our kitchen now, we use both methods, but I always have to show the new boys in the kitchen how to cook porcini slowly, because it isn’t the fashion in most kitchens.

In Italy, most people have a jar of porcini preserved under oil to serve as an antipasto, and a jar of dried porcini to use in risotto. I never saw porcini wasted at home – even the smaller, harder ones that we sometimes found, usually under the pine trees, where the sun couldn’t reach and the ground was completely dry. When we brought our baskets home, the softer, more mature mushrooms would he cooked straight away, and the harder ones would be either preserved or dried.

To preserve them, my grandmother used to bring to a boil a pan of about three parts water to one part vinegar with some salt, then she would put in the mushrooms, blanch them briefly, drain them, let them cool down, dry them, then put them into a sterilized jar and cover them with olive oil. Some people put in juniper berries or bay or rosemary, too. Preserved mushrooms were never used in cooking; just to serve with plates of salami – with chopped garlic and parsley sprinkled over the top. If I put mushrooms under oil now, I usually use chanterelles (see page 86), which appeal to more people, because porcini done in this way are definitely an acquired taste, a little slimy, like oysters, but I love them. For me, some porcini under oil, with artichokes preserved in a similar way, and cured meats, make a great starter – you don’t need anything more.