“I still remember my surprise at being offered such an unlikely combination as fish and broccoli in a restaurant in Bologna, where dishes outside the traditional, yet excellent, range of local cooking are viewed with suspicion.”

Anna Del Conte, Entertaining all’Italiana

Italian people tend to cook and eat in a very purist way – almost ferociously so sometimes. If you order fish in a traditional restaurant in Italy, that is exactly what you get – no vegetables, not even any salad leaves, just fish, usually whole, with its head on, and a piece of lemon. And I have to admit that some of the best meals I have had in my life have been that simple, just concentrated on one or two brilliant flavors. What is most important is not what you serve with the fish but its quality and how well you cook it.

Almost everywhere in Italy has access to fish: three-quarters of our regions have their own coastlines, and the rest have lakes and rivers. Even if fresh fish wasn’t readily available, there would always be cod that had been preserved either by salting at sea and then drying (baccalà), or by air-drying (stoccafisso or stockfish).

Italians also love sushi, perhaps because in certain areas, especially Puglia, Abruzzo and Marche, we have our own tradition of raw fish dishes. You go to a little restaurant in Puglia and they might bring you some raw prawns, just chopped in half with a lemon to squeeze on top; or there might be raw fish marinated in lemon juice or vinegar. And, at La Madonnina del Pescatore near Ancona, Moreno Cedroni has made famous his “susci and sushi” (he wrote the book of the same name) – an Italian take on the Japanese way with raw fish and rice.

I would like to say that we should eat fish as much as possible, because it is such a light healthy food, but we all know the damage we are doing to our seas with our greed for fish. We used to think we could go on taking what we wanted and the fish would just multiply and replenish themselves forever, but now we know that isn’t true. Seventy-five percent of the world’s fish stocks are either exhausted or overfished – cod and haddock are in real danger of extinction in the Atlantic – and it is a scandal that the enormous trawlers that rake the seabed, and destroy ecosystems in the process, pull in so much fish that is wasted because it is too small. Surely everything that comes up in the net should reach the market – not be chucked back into the water, dead?

I don’t think that farmed fish are the answer either. The biggest industry for farmed fish is salmon, which affects us very little at Locanda, as salmon is not a fish Italians traditionally cook (although smoked salmon has now become very popular for the Christmas lunch) – but what are these farmed fish eating? Mostly feed made from small fish – which only plunders the oceans even more. And what chemicals are being put into the water to control disease? It has become fashionable to create salmon farms in rough waters around the coast, so that the fish develop firm flesh from swimming against the tides, but when they are situated in the mouths of salmon rivers, do they pollute the wild fish on their way to the sea, or even escape and mate with them, creating weird unnatural hybrids?

If we aren’t going to rob the sea of its treasure forever, perhaps we have to learn to enjoy different varieties of fish – and to ask hard questions about whether it comes from sustainable sources, and how it was fished.

In Italy, we have a rather different tradition of sea fishing from that in the UK and the States. Instead of big trawlers staying out at sea for weeks, catching big fish that are destined to be cut up, Italian fleets tend to be smaller, spending less time out at sea, and often specializing in small “blue” fish, like sardines and mackerel, which I consider extremely valuable for our health, because they are rich in omega-3 oils. They are also so quick and easy to cook, perhaps wrapped in prosciutto and quickly fried in a pan with some red wine and vinegar whisked in to make a warm vinaigrette.

The fish come in from two seas, the cold, deeper waters of the Mediterranean and the warmer, shallower waters of the Adriatic, but even from coastline to coastline, though the species may be the same, the habitat changes, and with it the nature and quality of the fish – and also, confusingly, the name. In Italy, the same fish can have twenty-five different names. At Locanda, the boys in the kitchen are all the time coming into the office saying, “What is the English for this or that?” and looking things up in books so they can learn the words for the menus, and, when it comes to fish, there is a big, noisy “discussion,” because we cannot even agree a common name in Italian, let alone English.

You must remember that in Italy it is only relatively recently that ingredients have moved around the country, rather than staying localized. Now when I go to the Milano fish market the choice of fish from all over Italy is amazing, but at one time you ate only what was caught on your stretch of coastline, or the freshwater fish from the nearest lake or river.

In our house in Corgeno, we always had fish on Fridays, and often two or three more times during the week, but I only rarely saw anything other than the freshwater fish from Lago Comabbio, below my uncle’s hotel, La Cinzianella, or from nearby Lago Varese or Maggiore. The exceptions were the occasional mackerel from the Ligurian coast, the red prawns that came from San Remo once a week, and the salted cod (baccalà), bought in slabs, soaked in water or milk, and then cooked slightly differently in every region and village. In Lombardia, it was often cooked “in umido” – stewed with onions and tomatoes and served with polenta. Around Liguria, it was traditional to cook it with spinach, or fry it and serve it with a sauce made with garlic and bread crumbs; in Firenze it was first pan-fried and then stewed in tomato sauce; in Roma battered and deep-fried.

The lakes around Corgeno are deep, with a continuous force of water pushing through them from the rivers and glaciers in the mountains: perfect for the likes of eel, carp, pike, perch and the lavarello (which, just down the road around Lago Maggiore, is called coregone, or whitefish). This fish belongs to the salmon and trout family, and for many generations it was a staple for local families. It is a beautiful, distinctive fish with a white belly, silver sides and a back that is sometimes olive-green. Because it eats insect larvae and crustaceans instead of feeding from the muddy bottom of the lake, it has white, tasty flesh.

As with sea fish, however, stocks are suffering. Not, for once, from over-fishing, but because pollution – which has now been tackled – and more recently the warming of the planet are taking their toll. The waters of the lake are not as cold as they once were, so the habitat is changing, and not as many eggs are being produced, so there is a big regeneration process going on now, to restore the stocks of fish to the levels they were at when I was little. They were then so plentiful, you could put down a rod and you would catch something almost immediately.

Eel from the lake is traditionally stewed, usually with tomatoes, and in the spring with peas. Then there is pike (there is an old saying: “carne de lusso carne de musso,” which means that the flesh of the pike is a little like donkey meat) and also carp. These three are the predators, the sharks lurking and feeding in the murky slime at the bottom of the lake, and, to varying degrees, they can have a flavor that is “muddy” – not unpleasant, but just different from sea fish, and needing robust ingredients, such as onions and vinegar, to help their flavor. I read about a Chinese emperor who was so in love with one kind of freshwater fish – probably carp – from a particular region that he constructed a series of ponds all the way to his palace at the Forbidden City, so that the live fish could be transferred from one pond to another until they reached him. Maybe I am not that dedicated, but still I would love to get the English excited about freshwater fish, especially perch – my favorite – which, like the lavarello, eats insects and fish larvae, rather than other fish, and so doesn’t have such a muddy taste as carp or pike. Perch are native to England’s lakes and rivers – but how often do you see them in fish markets or restaurants?

Freshwater fish like perch tend to have softer flesh than sea fish. To turn that defect into an asset, we would usually fry it, so that you would have a crispy contrast on the outside. Often we would make a carpione, which is similar to a scabeccio, in that the fried fish is marinated in vinegar and oil with garlic and herbs, but it is usually served cold. Once the fish was under the marinade, it could be kept for 4 to 5 days, and the taste became even better as the time went on.

Another favorite local dish that I remember so well is perch with almonds. The almonds would be picked during the summer and dried in the sun, so that in September, when the perch is at its best, they would be ready. First you crushed your almonds, then filleted the fish and dipped the fillets in a batter made by first mixing egg yolks and flour, then whisking in the egg whites – and maybe a little beer – and some salt and pepper. The battered fish would be pan-fried in sunflower or vegetable oil, so that it was softer than the quite hard, crunchy batter that characterizes English fish and chips – which I love. While the fish was frying, you heated a little of the very white local butter in a pan, and then added some sage leaves and the almonds, let the butter bubble and froth until it just turned golden, then poured it over the battered fish. The nutty sweetness of the almonds infused the butter, and the flavors were brilliant. It sounds simple, I know, but it is one of those dishes that stays in your mind.

Despite my love of these kinds of fish, at Locanda I have to respect the fact that when people want to eat fish, they expect to see the varieties that are considered a bit more elegant, or fashionable: like turbot, sea bass and sole. Even so, when we cook them we draw upon the bread crumb and herb or tomato crusts, the olives, and the walnut pastes that my chefs all recognize from their mothers’ and grandmothers’ kitchens.

The perfect time to cook fish is within a few hours of its being caught, when the rigor mortis has disappeared but if you touch it, the flesh will spring back and your fingers will leave no dent. Always buy fish that smells only of the sea – it should never, ever smell fishy, as this means that it is old. Really fresh fish is lightly covered in clear slime (not opaque slime, which also shows that it is old), will be vivid red under the gills and have bright, shiny eyes.

At home, I love to bake big fish whole in the oven, but in restaurants, you have always to think in terms of individual portions – and we are the generation of the fillet, aren’t we? Twenty years ago, you ordered fish in a restaurant and it came with its skin and bones and head – the only thing you had filleted was smoked salmon. Now no one wants to see any bones, which is a great, great pity, because the bone – which imparts its milky gelatinous juices into the flesh of the fish as it cooks – has a great influence on flavor and texture. We have people in the restaurant saying, “I can’t eat turbot unless it is off the bone,” but if you cook a rich heroic fish like turbot without the bone, it loses its magic. So we say, “Okay, we’ll cook it on the bone, then take it off for you,” and they really notice the difference in flavor.

If you do want fillets, I would always say that instead of buying them in packages in the supermarket, you should try to buy the whole fish and take them off the bone yourself – or ask your fishmonger to do it for you – assuming you are lucky enough still to have a fishmonger – and ask him to give you the trimmings to make fish stock (see page 267).

Whereas meat can be quite forgiving if you overcook it a little, fish punishes you if you take your eye off it. If you are cooking fillets or steaks, the best way is to use a nonstick pan – almost essential in every restaurant kitchen these days. There is no point in talking about how long to cook a piece of fish, because it depends on its thickness – the trick is to know how to recognize when the fish is ready.

Heating up oil in a pan can be dangerous if you take your eyes off it, so heat the dry pan first, then you can put in a thin film of oil and, as it hits the hot pan, it will come up to temperature right away. You do need the oil to be really hot, because we are talking here about some aggressive cooking to crisp up the skin quickly – don’t be afraid of a bit of smoke.

Season the fish well, just before it goes into the pan. The salt will draw out a little moisture, helping the fish to crisp better (but if you season it too early, it will dry out the flesh). Then get your pan good and hot, put in the oil and, when you put in the fish, skin side down always, leave it where it is while the skin becomes really golden and crisp. Don’t be tempted to fiddle with it because, if you move it or try to turn it too early, you will leave the skin behind.

While the skin is crisping up, watch the flesh. As the heat travels upward through the fish, you can see that it turns from translucent to white and opaque. Keep watching and, as soon as it has turned opaque almost all the way up the thickness of the fish (by now the skin should also be crisp), flip it over, then immediately take the pan off the heat, and it is ready. Sometimes, especially if we are cooking fish in a bread crumb crust that we want to be really crunchy, we start the cooking on the stove, then transfer the fish (still in its pan) to a very hot oven – as in the sea bass recipe on page 408. In this case, to compensate for the extra few minutes of cooking time in the oven, we would flip the fish over earlier – when it has turned opaque about halfway up its thickness.

When my grandmother cooked fish, she would go out into the garden with the scissors and cut everything that grew there: sage, parsley, rosemary, chervil, wild garlic, the whole lot … her idea was that if an herb was growing next to the lake in which the fish was growing, all the flavors would naturally work together. I like the notion that what grows together goes together and I don’t think you should get fussy about what herbs go best with what fish.

I remember once, while on holiday, seeing a chef chop up parsley, sage, rosemary and garlic, packing the mixture on top of some oysters, topping them with bread crumbs, and putting them under the grill, then finishing with a grating of lemon zest. I thought, “Rosemary and sage? Surely they are reminiscent of red meat, not oysters?” And yet the combination was fantastic. The only herb I wouldn’t use is thyme or lemon thyme. For some reason, I just don’t like the flavor of thyme with fish.

The herb I probably love most is parsley – and when I say a handful of parsley, I mean a good, big handful. Ask my wife, Plaxy. Whenever she is cooking, I always seem to be telling her, “Put in some parsley,” then I see her chopping some puny little sprigs, and I say, “No! No! I mean really put parsley in! Masses.”

Branzino alla Vernaccia in crosta di pomodoro

For this dish, we use Vernaccia wine from San Gimignano, the quite dry, fresh and spicy wine that was favored at the royal court in Toscana during Renaissance times. It is a very simple recipe that relies on perfect fish with crispy skin and flesh that is just cooked through. You can really use any fish you like, other than flatfish like sole, hut if you are using sea bass, try to find wild fish, which are bigger and taste better. The sea bass we get are really big, weighing about 5 to 10 pounds each, and they give us fillets about ⅝ inch thick, which we can cut into portions. You are more likely to find smaller fish, but try to find the thickest fillets possible, because they are harder to overcook. With thinner fillets, by the time the skin crisps up the flesh is already in danger of being overdone.

2 tomatoes

3 tablespoons diced green olives

1 tablespoon sun-dried tomatoes

2 tablespoons bread crumbs

4 thick sea bass fillets (see above), each about 7 ounces

juice of 1 lemon

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

⅔ cup Vernaccia, or other spicy dry white wine

3 tablespoons fish stock

2 tablespoons chopped parsley salt and pepper

For the artichoke puree

2 large globe artichokes

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 white onion, thinly sliced

⅔ cup white wine

3 tablespoons heavy cream

3 pats of butter

Blanch the tomatoes, skin, quarter and deseed (see page 304), then cut into dice about the same size as the olive dice.

Put the sun-dried tomatoes into a food processor, process them quickly, then add the bread crumbs and whiz again until the tomato is absorbed into the bread crumbs and it looks a bit like a crumble mixture. Spoon out onto a tray and flatten down. Leave in a warm place in the kitchen for an hour or so to dry out.

Preheat the oven to 390°F and take your sea bass out of the fridge so that it can come to room temperature. Squeeze the lemon juice, put half to one side and add the rest to a bowl of water. Have this ready before you start preparing the artichokes for the puree.

To make the puree, snap off the artichoke stalks and discard them. With a small paring knife, starting at the base of each artichoke, trim off all the green leaves and put the artichoke into the bowl of water with lemon juice while you remove the leaves from the next one. Repeat with the remaining artichokes. Using the same paring knife, begin to trim away the white leaves from each artichoke until you are left only with a few tender ones surrounding the heart. Put back into the bowl of water and continue to trim the other artichokes, putting them into the water as soon as they are ready, so that they don’t discolor. Cut each artichoke heart in half, scoop out the hairy chokes and discard them. Leave the remaining hearts in the bowl of water until you need them.

Heat a saucepan, add the olive oil and then the sliced onion. Cook for about 10 minutes until the onion is soft but not colored. Thinly slice the artichoke hearts, add them to the onion and cook for another 5 minutes, then add the white wine. Allow the alcohol to evaporate completely (about 15 to 20 minutes) and then add 1 cup water. Continue to cook for another 20 minutes or so, until the artichokes are soft and all the water has disappeared – keep an eye on the pan and stir as the water evaporates, to avoid the artichokes catching fire and burning.

Transfer the contents of the pan containing the artichokes to a food processor and puree until smooth.

Put the cream in a pan and boil it to reduce it by half. Add the artichoke puree and let it cook for a few minutes. The resulting puree should be soft but firm enough for the sea bass to sit on top; if you feel that it is too wet, let it cook a little longer to dry it out. When it is ready, season to taste, cover and keep to one side.

Take an ovenproof nonstick frying pan big enough to fit all the fillets comfortably and get it hot on the burner. (If you don’t have a big enough pan, you will need to cook the fillets in two batches.) Lightly season the fish on the skin side, put a tablespoon of olive oil into the pan (it will heat up instantly) and add the fillets, skin side down. As the heat goes through the fish, it will turn from translucent to white and opaque.

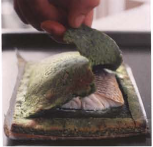

As soon as the fillet has turned white halfway up the fillet, turn it over (the skin should now be crisp and golden) and sprinkle with the dried bread crumb and tomato mixture. Pour the wine into the pan (around, not over the fish) and transfer to the oven for a couple of minutes. The bread crumbs will crisp up and become darker in color.

Take the pan from the oven and lift the fish onto a warm plate. Put the pan back on the heat, add the olives and fish stock, and bubble up so that it reduces by half. Then put the sea bass back into the sauce, crust upward, for a minute or so to heat through.

At the same time, put the artichoke puree back on the heat to warm through. Stir in the butter and, when the puree is hot, spoon it onto your plates and put the fish on top.

To the pan in which the fish has been cooked, add the reserved lemon juice, the rest of the olive oil and the parsley then spoon this mixture around the fish and serve.

Branzino in crosta di sale e erbe

Baking inside a crust of salt is one of the oldest ways of cooking fish, which has become fashionable all over again. Originally it would have been done by simply sprinkling a layer of sea salt in a dish, laying the whole fish on top, then burying it with more salt and perhaps some herbs, and sprin-kling the salt with water, so that it stuck together and formed a crust. The idea is that, as the fish cooks, the salt flavors the flesh but also forms a barrier against the heat, so all the juices stay inside. In the restaurant we do this more elegant version, using a more sophisticated crust, which is more like a dough, made with salt, flour and egg whites, which can be easily molded and becomes rock-hard in the oven. It is important that the fillets of sea bass are all the same thickness, rather than, say, two thick ones and two thin tail ones, so that they all cook for the same length of time.

At home, though, it is lovely to do this with a whole fish (scaled and cleaned) – stuff the cavity with some fresh herbs, and allow around 20 minutes baking time for a fish of about 4 pounds (test to see if it is ready, as in the recipe below).

You need a lot of egg white for this recipe, but don’t waste the yolks – you can use them to make pasta (one of the reasons we dreamed up this way of making the crust is that we always have lots of egg whites left over after we have made our pasta).

If you happen to have any aged balsamic vinegar (see page 46) – which is very expensive but beautiful – then, instead of the dressing, just pour a little around the fish, with some good olive oil.

4 handfuls of spinach

5 ounces basil, trimmed

5 ounces parsley, trimmed

1 ounce rosemary leaves

1 ounce sage leaves

4 cups sea salt

5 ¼cups all-purpose flour

⅔ cup egg whites (about 6–8 eggs), plus 1 yolk for brushing

4 sea bass fillets, each about 7 ounces, of a consistent thickness, i.e., with no thinner tail parts

2 pats of butter

1 tablespoon olive oil salt and pepper

For the balsamic dressing:

8 tablespoons good balsamic vinegar

1 teaspoon honey about

1 tablespoon sugar

juice of ½ lemon

½ tablespoon olive oil

2 drops of Worcestershire sauce

Preheat the oven as high as it will go.

Blanch the spinach leaves in boiling salted water for the briefest time (5 to 10 seconds only), then drain and squeeze out the excess water.

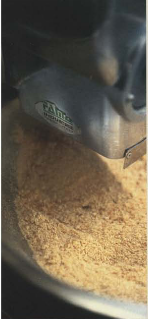

Mix the herbs together. Either put the sea salt into a food processor and crack it a little, then add the herbs and process until the herbs are very finely chopped, or do this by hand.

If you have a food processor, put the flour, egg whites and the salt and herb mixture into it, and process to a green dough. Otherwise, mix the flour and the salt and herb mixture well in a mixing bowl, then transfer to a clean work surface, pile up like a small mountain (which we call a fontana or fountain) and make a well in the middle. Beat the egg whites lightly in a bowl, then pour them into the well in the flour. Put in your hand and slowly and gently turn it, working in a little of the flour mix at a time, so that the egg white is absorbed gradually and forms a dough.

Knead the dough for 3 to 4 minutes. If it feels too hard as you work it, wet your hands with a little water, which should help to loosen it. The dough needs to be firm and elastic enough to enclose the fish without breaking but not too loose; otherwise when it cooks it will release too much moisture, and the fish wont cook properly. Wrap the dough in plastic wrap and keep to one side.

Make the balsamic dressing: put the balsamic vinegar in a bowl, add the honey and sugar, and leave in a warm place (but not on the stove), so that the honey and sugar can dissolve into the vinegar. When they have, add the lemon juice, olive oil and Worcestershire sauce. Taste and, if you think it is too sharp, add a little more sugar to taste. Keep to one side.

Roll the dough out to about ½ inch thick. You need to cut this into 8 rough squares of dough – 4 to go beneath the fillets (make these about ¾ inch bigger all round than the fish) and another 4 to go over the top of each fillet to enclose them completely (these top squares will need to be about 1 ¼ inches bigger all around than the fish). Each fillet will be slightly different, so use them as a guide when you are cutting out your dough.

Lay out the 4 squares of dough that will go underneath the fish and place a fillet on top of each, skin side facing upward, then brush the edges with beaten egg yolk and put the top square on top. Seal tightly and trim the edges neatly. Make sure there are no holes in the dough; if there are any, take a piece of the dough trimmings, wet it with water and use it to patch the hole. Brush with more egg.

Line a flat ovenproof tray with baking paper, put the sea bass “parcels” on it and place in the preheated oven. The length of cooking time will depend entirely on the thickness of the fish, so start testing after about 7 minutes (but bear in mind you might need up to 10 minutes or so more). Take one of the sea bass out – the crust will now be golden and hard – and, with a sharp knife, cut around three sides, so you can lift up the crust like a lid, and check the fish inside. Press your finger against the fillet: if it is soft, then it is ready; if the flesh of the fish is resistant, replace the “lid” and put back in the oven. Test again after a couple of minutes or so.

When the sea bass is ready, take it out of the oven and leave it in its crust, while you warm up the spinach in a saucepan with the butter and the olive oil. Season with salt and pepper. Arrange in the middle of your plates.

With a knife, cut the crusts all the way round and lift off the tops. With a spatula, lift out the fish and put them on top of the spinach. Finish with the balsamic dressing and serve.

The rich flavor of sea bass marries really well with basil and potatoes. When you make potato puree, it is important to use the right potato – you want ones that are not too starchy. As always, we cook them with the skin on to keep in all the flavor. Once the water comes to the boil, we turn down the heat and let them cook very slowly This will keep the skins from splitting, and stop water getting inside, which will spoil the floury texture. The potatoes are ready when a sharp knife goes through them easily. If they fall apart, they are overcooked. When they are ready, you need to work quickly – have the milk ready and warm, peel the potatoes as soon as they are just cool enough to handle, and put them through a very fine sieve right away (it does need to be very fine, so that you get a smooth puree). Return them to the hot pan and make sure once they are pureed that they are kept hot. If you lose the heat, the puree will lose flavor and become grainy in texture.

2 large bunches of basil, trimmed

7 tablespoons unsalted butter, softened

2 large red potatoes, preferably Desiree, unpeeled

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon milk

4 teaspoons sunflower or vegetable oil

4 sea bass fillets, each about 7 ounces

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

salt and pepper

Put the basil leaves in a food processor and chop them, then add the butter and process to a bright green paste. Spoon into a container and leave in the fridge until you need it.

Put the whole unpeeled potatoes in a pan of cold salted water. Bring to the boil, then turn down the heat to a simmer and cook until soft (about an hour, depending on the size).

When the potatoes are nearly cooked, warm up the milk in a pan – don’t let it boil, just heat it through, so that it wont bring down the temperature of the potatoes when you add it to them.

Peel the potatoes when cool enough to handle and, while still hot, put through a fine sieve. Add the milk and season. Keep in a warm place.

Meanwhile, heat two nonstick pans and divide the sunflower or vegetable oil between them.

Season the fish fillets and put them into the pans, skin side down. Gently press the fish down, so that the skin is all in contact with the pan, and cook until it turns golden and crisp, and you can see the flesh gradually turning white and opaque almost to the top. Turn the fillets over and turn off the heat.

Cut the basil butter into cubes. Put the potato puree back on the heat and beat in the cubes of basil butter.

Spoon some of the potato puree into the middle of each of your serving plates. Lift the fish out of the pan, place on top of the puree, drizzle each fillet with olive oil and serve.

You can also do this with swordfish (pesce spada), which is actually more typical in Italy. Ask your fishmonger to give you quite large steaks, not cut from the tail, as you need them to be about 3 ¼ to 4 inches in size and around ⅝ to ¾ inch thick. This a recipe that is best in the summer, when the tomatoes are good – look for the juiciest, sweetest ones you can find. Whenever we are serving a salad of arugula and tomatoes, we season the tomatoes separately, as they need more salt and vinegar.

4 tuna or swordfish steaks, each about 7 ounces

around 24 cherry tomatoes, or 5 large tomatoes

3 tablespoons white wine vinegar

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

4 handfuls of arugula

3 tablespoons Giorgio’s vinaigrette (see page 51)

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 lemon, cut into quarters salt and pepper

Get a griddle pan or grill smoking-hot. Meanwhile, take the fish out of the fridge and let it come to room temperature.

Cut the tomatoes in half if small, quarters if large. Put into a bowl, season well with salt and pepper and toss with the vinegar.

Season the fish steaks and sprinkle with parsley. Cook the steaks 2 at a time for about 2 minutes on one side, then turn them over and give them another couple of minutes on the other side for fish that is still rare in the middle (cook for longer if you don’t like it like this). Keep warm while you cook the other steaks.

While the fish steaks are cooking, season the arugula with salt and pepper and dress with Giorgio’s vinaigrette.

Arrange the tomatoes on the plates, the rocket on top and place the fish steaks on top of that. Finish each steak with a little extra virgin olive oil and serve with a lemon quarter.

“You have to smell them all”

When we are out shopping, my wife, Plaxy, always says, “Why does it take you two hours to buy three lemons?” “Well,” I say, “because there are so many lemons, and there must be some that are good, some not so good; so you have to smell them all.” For me the leaves tell the tale. The fresher the leaf, the less time the lemon has been off the tree. Look for lemons that are unwaxed and have a lively-looking skin. A good lemon feels firm when you squeeze it. My favorites are the really thick-skinned ones, whose juice seems to have a slightly less aggressive flavor.

Lemons are so important in Italian cooking – we use their zest and juice in everything from fish dishes to salads, stews, and desserts. Around the country you will find risotti flavored with the zest and juice, and pasta tossed with lemon juice, butter, cream and Parmesan. But we are not talking about just any old lemons – they have to be big and scented, and full of powerfully flavored juice that has a slight sweetness, taking the edge off the acidity. So, if you squeeze them over cooked fish, the flavor is less harsh, and if you use them in a marinade, they don’t “cook” the flesh too quickly.

The lemons I love best are from either Sorrento or Sicilia, where we go on vacation sometimes in the summer and where every house seems to have a lemon tree. You see the old men picking boxes of lemons in the morning when the sun comes up, then driving them in their three-wheelers to the local bar; and the scent that rises up from the fruit is fantastic. Order a fish in a café or restaurant, and they don’t just give you a slice of lemon, or a quarter, they give you a whole lemon to squeeze over it.

From Sorrento, we get the beautiful Femminello lemons, which are the ones that are used for the local limoncello liqueur, made by infusing the lemon peel in alcohol. Since 2000, Sorrento lemons have achieved Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) status, which specifies that they can be grown only in the Sorrento peninsula, or on Capri, and they must weigh at least 3 ounces. They are planted in straight lines on terraced slopes going down to the sea and sheltered under pagliarelle (straw mats) that are attached to chestnut poles, to protect against the salty sea air and help the fruit to ripen evenly.

The lemons grow all year round, but are at their best between May and the end of October. During the peak times for picking you see everyone running around like monkeys, with bags of lemons on their backs, picking from miles and miles of terraces covered in bright yellow perfumed fruit; it is quite beautiful to see.

Hake, also known as whiting, is such a lovely fish, but it isn’t used as much as it should be. You can do this dish either with fillets or, if the hake is quite small, ask your fishmonger to cut steaks – across the fish – arid serve it on the bone. You really need a mandoline for this, so you can slice the fennel very, very fine. As the hot scabeccio is put on top of the fennel, it cooks some of the slices slightly, softening them. It is this contrast with the lovely crunch and freshness of the rest of the fennel that makes it come alive and sing out above the other flavors.

4 hake fillets or steaks (see above), each about 7 ounces

2 lemons

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 small fennel bulbs salt and pepper

For the scabeccio:

8 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, thinly sliced handful of parsley leaves

8 tablespoons white wine vinegar

pinch of sugar

Preheat the oven to 390°F. Prepare 4 pieces of foil, each twice the length of the pieces of fish. Cut one of the lemons in half and squeeze some juice over each piece of foil. Place the fish toward one end of each piece of foil and season. Drizzle each with 2 teaspoons of the olive oil. Fold the remaining foil over the top and fold the edges over to seal all the way round, so you have 4 foil parcels. Make sure the fish is sealed in properly and there are no holes in the foil; otherwise the steam will be lost and the fish won’t cook properly.

Slice the fennel very, very thin and put the slices into a bowl. Mix the juice of the other lemon with the remaining oil and use to dress the fennel. Season.

Put the fish parcels in the oven. Depending on the size, you will need to cook them for between 4 and 8 minutes. Check the largest fillet (they will inevitably be slightly different sizes) by testing with your linger: the flesh should still be soft and moist – don’t worry if you think it is slightly undercooked, as the hot sauce you are going to pour over it will finish cooking it on the plates.

While the fish is cooking, make the scabeccio: heat a small pan, add the olive oil and the garlic, and let it fry gently. When it starts to color, add the parsley – be careful, as the water in the parsley may cause the oil to spit a little. Leave for a minute or so to bring the oil back up to temperature, then, very slowly, add the vinegar and then the sugar. It will bubble up and evaporate a little, leaving its flavor without the sharp smell.

By now the fish should be ready, lake it from the oven but don’t open the parcels immediately.

Arrange the fennel salad in the middle of your plates. Open the parcels and lift out the fish with a spatula. Place on top of the fennel. Spoon the juices over the top, followed by the sauce, and serve.

Sgombro alla griglia con crosta di erbe

Mackerel is another fantastic but underrated fish, which is marvelous cooked inside a crispy herb crust that protects the fish, keeping it moist and trapping in all the delicate flavors. You can do this with mackerel fillets, too, in the same way, but leave out the stuffing and cook the fillets, skin side first, for 2 to 3 minutes depending on the thickness, then turn over for a further 2 to 3 minutes.

4 tomatoes

½ cup plus 1 tablespoon olive oil

4 white onions, cut into about ½inch dice

3 tablespoons white wine vinegar

4 tablespoons salted capers (preferably baby ones), rinsed

4 medium-sized mackerel, gutted

4 sprigs of rosemary

4 garlic cloves

4 handfuls of mixed salad greens

4 tablespoons Giorgio’s vinaigrette (see page 51) salt and pepper

For the herb crust:

small bunch of parsley, trimmed

small bunch of rosemary, trimmed

bunch of basil, trimmed

bunch of sage

1 scant cup bread crumbs

3 tablespoons olive oil

Blanch the tomatoes, skin, quarter and deseed (see page 304), then cut into ¾-inch dice.

Get a griddle pan or grill smoking hot.

To make the herb crust, put the herbs into a food processor with the bread crumbs and a little of the olive oil, and process. Then slowly add the rest of the oil until you have a quite oily paste. Transfer to a large tray or plate.

Put 2 tablespoons of the olive oil into a pan, add the onions, cover and cook gently for about 10 minutes, until they become translucent but not colored. Add the vinegar and cook for another 2 to 3 minutes. Add the capers and set aside.

Season the fish lightly inside and stuff each one with the rosemary sprigs and garlic cloves (crush them lightly first). Season the outside of the fish. Brush another 2 tablespoons of the remaining oil over the fish, then roll it in the herb and bread crumb mixture, making sure it clings well.

You should be able to cook 4 fish at the same time. Place them on the hot griddle pan or grill and cook for about 4 to 5 minutes on one side (depending on the size) so that it marks well but doesn’t burn (turn down the heat if necessary). Turn over and cook for another 4 to 5 minutes.

While the fish is cooking, put the salad leaves in a bowl, season and toss with the vinaigrette.

Put the pan with the onions back on the heat to warm through. Check and adjust the seasoning, if necessary. Stir in the diced tomato.

Divide this mixture between 4 plates and arrange the salad on one side of each. Lay the fish on top of the onions and drizzle the remaining olive oil over.

I wish I could entice more people to eat eel. The Romans loved it and it often appears on the menus of Renaissance banquets. In Italy, there are two ways to cook it: braised slowly (though I never saw eels in jelly before I came to London), or cooked hard over a high heat. I love it chargrilled in an herb and bread crumb crust, or the way Vincenzo Borgonzolo cooked it for me one night after service had finished at Al San Vincenzo. He tossed it in flour, then pan-fried it and squeezed lots of lemon juice over it. Before I tasted it, I would never have believed that lemon would be good with eel; the two seem to be such opposite flavors, but the lemon seems to grab hold of the oiliness of the eel, and change its character completely so that it melts in your mouth, and the flavor is brilliant. If you gave that dish to 20 people, probably only a few would recognize it as eel. Such a simple, perfect piece of cooking.

I later discovered that this dish has its roots in some of the old recipes collated by Artusi, the great nineteenth-century Italian food writer, who reckoned that medium-sized eels can be cooked on the grill without skinning (which is necessary for large ones), as the skin “when seasoned with lemon juice at the moment of serving, is not unpleasant to the taste when you suck on it.” Often the eel is threaded on skewers, interspersed with sage or bay leaves and pieces of bread, and then put on the grill for 10 minutes or so until the eel is cooked through and the bread toasted. Then it is served, again with lemon juice squeezed over.

In my region of Lombardia, it is stewed with tomatoes and, sometimes, peas. Peas are also a favorite in eel recipes from around Venezia. Elsewhere, it is typically stewed in wine. According to Artusi, in Firenze they marinated the eel in oil and salt and pepper, then rolled it in bread crumbs and cooked it with garlic, sage and seasoned oil in a cast-iron pot, “with fire above and below.” Then, when it started to brown, they added a little water to the pan.

Many of the recipes come from the lagoons of the Valli di Comacchio in the Po delta, in the northeast of Italy, where the best eels are reckoned to come from. Here they tell beautiful stories about the dark stormy nights of la calata “the descent,” when in November and December the eels leave the fresh water in which they have spent most of their lives and head out to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. The fishermen built intricate traps in a series of linked basins, called lavorieri, to catch them at this time, when they have changed color from yellow or brown to silver and would be at their fattest, ready to take on the long journey. Then when the young “glass eels” or elvers returned from the sea in January and February to make la montata, the ascent into the marshes and rivers, they would be caught again in the lavorieri, and the salt water would have enhanced their flavor. During the brief season, bands of eel workers would arrive in Comacchio and stay in special very basic houses, called casoni, from where they sent the live eels in boats to Venezia, or fried them, marinated them in oil and vinegar and packed them in big barrels.

Everywhere you go in Comacchio today there are shops selling live eels, or eels that have been smoked, or fried and then marinated in the traditional fashion, and they are on every menu in every restaurant, maybe salted, or with cabbage or in brodetto or risotto. Artusi reports an old recipe from this region that he tried for eel “stew” or umido (which means “humidity”) that I particularly like the idea of. You take a couple of pounds of medium-sized eels, with the skin on, and cut them into segments, but leave them connected together by a strip of flesh. Then you coarsely chop three onions, a celery stalk, and a carrot and some parsley, and parboil them in about two glasses of water with the peel of half a lemon and some salt and pepper. Then you take an ovenproof pot and put in a layer of eel, followed by a layer of vegetables (discard the lemon at this point), then another layer of eel, and a final layer of vegetables, and top with their cooking water. You cover it tightly with a lid and let it cook very slowly in the oven (Artusi buried his pot of eels in ashes and coals in front of a wood fire) so that the eel gives up its own juices, shaking and turning the pot, but not stirring or you will break up the eel. When the pieces of eel start to pull apart and are almost cooked, you add a generous tablespoonful of strong vinegar mixed with a touch of tomato paste, taste and season generously if necessary. Bring it to the boil for a little longer, to finish off cooking the eel, and that is it; you take it off the heat and serve it with warm bread.

Trancio di merluzzo con lenticchie

I made this for the first time in Olivo. Tony Allan, who supplied our fish, brought me some cod, which I cooked in a pan, and I happened to have some lentils there for another dish. I put the two together, and thought the flavors were amazing; and the flakiness of the really fresh cod worked so well with the flouriness of the lentils. In Italian cooking you find some stews of fish with lentils, but they are longer-cooked, whereas part of the pleasure of this dish comes from the crispy skin of the pan-fried cod. God is one of the most overfished fish, so buy it only from genuinely sustainable sources, and preferably line-caught rather than landed by trawler.

2 handfuls of parsley

½ cup plus 1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

4 large cod fillets (from the center of the fish), each about 8 ounces (½ pound)

3 tablespoons sunflower or vegetable oil

3 ½ tablespoons butter, cut into small cubes

a few rosemary leaves to garnish salt and pepper

For the lentils:

1 ½ cups green lentils (preferably lenticchie di Castelluccio)

1 white onion

1 carrot

1 celery stalk

1 small leek

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

3 ½-ounce piece of unsmoked pancetta sprig of rosemary small bunch of sage

2 bay leaves

6 cups vegetable stock (see page 268) handful of parsley, chopped

3 ½ tablespoons butter, cut into small cubes

Prepare the lentils: soak them in water for half an hour, then drain. While they soak, finely chop the vegetables.

Heat half the olive oil in a pan and add the chopped vegetables and the piece of pancetta. Cook for 5 to 10 minutes, until the vegetables are soft but not colored. It is important that the vegetables be soft, so that they release all their sweetness, flavor and moisture into the lentils.

Add the lentils together with the herbs, all tied together, and cook for 5 minutes, stirring until everything is well mixed and the lentils start to stick to the bottom of the pan. Don’t season at this point, as salt will make the lentils harden.

Add around 4 cups of stock (to cover the lentils by about a linger) and keep the rest hot on the burner in case you need it. Bring the contents of the lentil pan to a boil, turn down the heat and simmer for 4 5 minutes until the lentils are soft, adding more stock if they begin to get dry. Remove the pancetta and keep the lentils on one side, but keep the stock hot in case you need to loosen the lentils before serving.

Put the 2 handfuls of parsley into a food processor with the olive oil and process as quickly as possible until you have a bright green sauce.

Season the fish. If you have two large nonstick frying pans, heat them at the same time and divide the sunflower or vegetable oil between them. When it is just beginning to smoke, put in the fish, skin side down, and keep pressing down and checking underneath – the skin should turn crispy and golden brown. You will see the flesh beginning to turn opaque. When it has turned white almost all the way through, turn it over. Divide the butter between the two pans.

While the butter is foaming, put the pan of lentils back on the heat – the lentils need to be the consistency of a risotto, not “soupy,” or they will be too loose after you add the butter: so, if necessary, drain off a little of the liquid. Add the parsley and stir in the butter. If, on the other hand, the lentils are not loose enough, you can add a little of the reserved hot stock. Check the seasoning and adjust if necessary.

Spoon the lentils onto the plates, with the parsley sauce on the side. Tilt each pan containing the fish toward you so that the buttery juices collect in one spot, then spoon this over the top of the fish. Lift the fish out and serve on top of the lentils.

This is a favorite dish that we have been cooking for many years. John Dory has a kind of metallic taste that I like, which amazingly comes through the flavors of the crispy potatoes, the wine and olives. We use Cerignola olives for this – the giant green ones from Puglia – but any large olives are good. Just remember that, if they are salted, you need to wash them well before you use them, or the salt will affect the flavor of the dish. I love to make this with Jersey Royal potatoes when they come into season, because they are so light and less floury than many other varieties.

16 new potatoes (whole and scrubbed but unpeeled)

around 20 very big green olives, with pits

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil, plus more to serve

1 wineglass of dry white wine

about 5 tablespoons Fish stock (see page 267)

2 tablespoons sunflower or vegetable oil

4 skinless John Dory fillets, each about 6–7 ounces

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

1 lemon

salt and pepper

Cook the potatoes in salted water from cold for about 15 to 20 minutes until slightly undercooked. Take off the heat, drain and, when cool enough to handle, peel. Cut the potatoes in half and keep to one side.

With a knife, take the flesh off the olive pits and set aside.

Heat half the olive oil in a large sauté pan, then put in the potatoes and cook until nice and golden and crusty – don’t worry if they break up a little. Add the olives and toss for a minute or so. Add the white wine and allow to evaporate, then add the fish stock and cook for a minute or so more. Season and turn off the heat.

If you have two nonstick pans, get these hot at the same time. While they are heating, season the fish. Divide the sunflower or vegetable oil between the two pans – it will get hot immediately. Put in the fillets (if you can tell on which side the skin has been, this should be facing upward – if not, don’t worry). Cook on one side until golden underneath – you will see the heat going upward through the fish, turning it opaque. When it is opaque almost to the top, flip the fish over, then turn off the heat and leave to rest for a minute or so.

While the fish cooks, turn the heat on again under the pan of potatoes and cook for a minute or so, until the mixture is quite soupy. Add the parsley, spoon on to the plates, and serve the fish on top. Drizzle with extra virgin olive oil and a squeeze of lemon juice.

Coda di rospo in salsa di noci e agrodolce di capperi

Monkfish needs to be treated more like a beefsteak than some of the more delicate fish – partly because the flesh is firm and dense and “meaty,” and partly because it contains more moisture than other fish. So you need to sauté it quite aggressively at first on both sides, then turn the heat down to let it cook through gently. The fish should be nice and golden after 3 to 4 minutes (if it doesn’t color much, it isn’t absolutely fresh). You can buy good walnut paste in Italian delicatessens, or make it (see page 322).

You need only around 1 ½ tablespoons of the agrodolce sauce, but it is easier to blend a larger quantity. Any you don’t need you can keep in the fridge for several weeks and use with roast fish or meat (remember, though, that it is quite sweet, so it is good to offset it with something a little bitter, like chicory or endive or Swiss chard).

2 tablespoons walnut paste

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 Swiss chard stalks with leaves

2 tablespoons vegetable or sunflower oil

4 monkfish tails, each about 8 ounces (½ pound)

4 tablespoons Giorgio’s vinaigrette (see page 51)

12 caper berries

2 handfuls of arugula salt and pepper

For the agrodolce sauce:

5 tablespoons white wine vinegar

⅓ cup sugar

3 ½ ounces (about ¾ cup) capers in brine, drained, washed and dried

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

Make the agrodolce sauce by putting the vinegar and sugar in a small pan and letting it bubble up and reduce to a clear syrup.

Hand-blend the capers, very slowly adding the syrup (as if making a mayonnaise), then blend in the oil (again very slowly, so that the sauce doesn’t split) until creamy Transfer to a small pan and keep on a very low heat, without boiling, for about 15 to 20 minutes, until any excess liquid disappears and the sauce is very thick. Leave to cool.

Mix 1 ½ tablespoons of the agrodolce sauce with the walnut paste, then slowly mix in the vinegar and half the olive oil. The sauce will become paler. Keep warm.

Separate the chard stalks from the leaves. Cut the stalk across into batons about ¼ inch wide. Blanch these in boiling salted water for a couple of minutes, lift them out with a slotted spoon and keep on one side. Then put the whole leaves into the water and blanch for a minute or so. Drain and squeeze the leaves, then chop coarsely. Put the stalks and leaves in a bow4, mix together and keep on one side.

Put a nonstick pan (or two, if necessary) on to heat. Add the vegetable or sunflower oil. Season the fish, put in the pans and cook quickly for 3 to 4 minutes on each side (depending on the size), then turn the heat down, and let the fish relax for a couple of minutes.

Season the chard and toss with half the vinaigrette. Mix the caper berries with the rocket, season and toss with the rest of the vinaigrette.

Spoon the reserved sauce onto the plates, arrange the chard on top, then the fish on top of that. Spoon the pan juices over, drizzle with the rest of the olive oil and finish with the arugula and caper berry salad.

Trancio di rombo ai funghi porcini con pure di patate

Roasted turbot (or brill) with porcini and potato puree

My granddad would turn in his grave if he knew I cooked mushrooms with fish. He would never ever have put them in the same dish, but there is something about the two flavors, brought together with parsley, that I have to say is weird, traditionally, but works very well, because of the richness and sweetness of the turbot (or its cousin, brill – this is one dish I wouldn’t do with a “poor” fish). You need to make it when the porcini are abundant, so you can choose ones with large caps (cappella). The trick is they go in right at the end, so when the dish arrives at the table, you smell them first.

2 large red potatoes (preferably Desiree), scrubbed but unpeeled

14 ounces fresh porcini (ceps), sliced very thinly

7 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 garlic cloves, chopped

½ wineglass of white wine

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon milk

2 tablespoons sunflower or vegetable oil

4 turbot or brill steaks on the bone, each about 7 ounces

handful of chopped parsley

salt and pepper

Put the whole unpeeled potatoes in a pan of cold salted water. Bring to a boil, then turn down the heat to a simmer and cook until soft (about 30 minutes to an hour, depending on the size). While the potatoes are cooking, brush, clean and slice the porcini (see page 239).

Melt 2 tablespoons of the butter in a sauté pan, add the garlic and cook without allowing it to color for a minute or so. Add the mushrooms and gently toss without frying. Add the white wine and let the alcohol evaporate. Season, then turn down the heat, cover with a lid and let the mushrooms stew gently for a couple of minutes. Take off the heat and keep on one side.

When the potatoes are nearly cooked, warm the milk in a pan.

Peel the potatoes as soon as they are cool enough to handle, and push through a very fine sieve. Put back into the pan and beat in half the remaining butter and the warm milk (you should have a very smooth puree). Season with salt only. Keep warm (cover the pan with plastic wrap to stop the potato from becoming dry and crusty on the top).

Meanwhile, heat 2 nonstick pans if you have them and divide the sunflower or vegetable oil between them. Season the fish and put into the pan, skin side down. Cook until the skin turns golden and crunchy, and you can see the flesh has turned from translucent to white and opaque almost to the top. Turn over and turn off the heat.

Return the pan of potato puree to the heat. Warm through and then beat in the remaining butter.

Put the pan containing the mushrooms back on the heat, and heat through. Stir in the parsley.

Spoon some of the potato puree into the center of each of your serving plates, arrange the mushrooms around it and place the fish on top.

Sogliola arrosto con patate, fagiolini e pesto

Sole isn’t big in Italy, but the Dover sole you can buy in the U.S. is a beautiful fish that deserves everything good that has been written about it. This is a late spring/summer dish, which is the time when the Dover sole are at their best. The mixed vegetables are held together in a “sauce” that is made using just potatoes and onions cooked together and pureed in a blender. The cooking of the vegetables may seem a bit time-consuming – we cook each one separately, drain them and refresh under cold water before putting the next vegetable into the cooking water – but each vegetable will taste much better and keep its bright color.

You don’t need to include all of the vegetables; you can vary them, according to what you have – just fresh peas, if you like, in season. The important thing is that if you use fava beans, cook them last. If you were to put them in first, they would turn the cooking water dark green and any delicate vegetables that followed, like peas, would darken too.

3 medium potatoes

5 tablespoons olive oil

1 white onion, chopped

4 tablespoons fresh peas

4 snow peas

12 long green beans

4 tablespoons fresh fava beans

4 tablespoons cooked cranberry or cannellini beans (see page 183 for how to cook the beans)

3 tablespoons vegetable or sunflower oil

4 Dover sole, each about 1 pound, heads and skin removed, and trimmed

4 squash flowers (if available)

4 tablespoons Pesto (see page 309) salt and pepper

Peel the potatoes and cut 2 into ½-inch dice. Put into a pan of salted water, bring to a boil, then turn down to a simmer for a minute or so, turn off the heat, cover with a lid and leave to finish cooking.

In a separate pan, heat a tablespoon of olive oil, add the onion and cook gently for about 5 minutes, without allowing it to color.

Roughly slice the third potato and add to the onion. Cook for a couple of minutes. Add water to cover and cook until the potato breaks up.

Bring another pan of salted water to a boil, put in the peas and let them cook for a minute or so, lift out with a slotted spoon and refresh under cold running water, then transfer to a dish or plate. Next, put the snow peas into the cooking water and repeat the cooking, draining and refreshing process. Keep these separate from the peas. Do the same thing with the long green beans, and finally the fava beans (these need to be last, or they will turn the water dark green, see above).

Put the onion and potato mixture into a blender and blend until you have a thick “sauce,” the consistency of a milk shake.

Split the green beans lengthwise, and slice the snow peas. Drain the potato dice, add to the beans and snow peas, then add the peas, fava beans and cranberry or cannellini beans. Season and mix lightly.

Heat 2 nonstick oval pans if you have them and divide the vegetable or sunflower oil between the two. Season the fish and put 2 in each pan. Cook gently for about 6 minutes on one side until golden, then turn and cook for another 6 to 8 minutes. If you press with your thumb the fillets should start to pull apart.

While the fish are cooking, put the mixed vegetables into a saucepan, add the potato “sauce” and warm everything up. Season.

Spoon this mixture into the middle of your plates. If you have any zucchini blossoms, arrange these around the outside, place the fish on top of the potato and vegetable “sauce,” spoon some of the remaining olive oil over each piece of fish, and drizzle the pesto around.

I love this dish. I’m very proud to have stolen the outline of the idea from a dish created by Jacques Rolancy at Le Laurent in Paris, which he based on something he had seen done by the great French chef Alain Chapel. In Paris the dish was overcomplicated, with quenelles of tapenade and shaped tomatoes and potatoes, but the combination of the flavors of fish, spinach, tapenade and balsamic vinegar was a fantastic one. When we opened Zafferano, I remembered it and started to work on the idea, putting in some crunchy chives and radish, some spinach, and a dressing made with balsamic vinegar. I only occasionally put balsamic vinegar with fish, because it has such an intense flavor, but here it is softened by honey and lemon, and we use a light Ligurian olive oil, as you don’t want one that is too strong and peppery. Over the years we have played around with this dish so much, but now I think we couldn’t get it any better. I am very wary of saying that I “created” anything in the kitchen – but this dish I do now consider to be “mine.”

4 handfuls of spinach

5 large radishes small bunch of chives, cut into batons

4 sea bream fillets, each about ½ pound, cleaned and pin bones removed

4 teaspoons sunflower or vegetable oil

2 tablespoons unsalted butter

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

4 teaspoons black olive paste (tapenade)

4 tablespoons Balsamic dressing (see page 411)

1 tablespoon sesame oil salt and pepper

Blanch the spinach in boiling salted water for 10 seconds – virtually just in and out – so that you keep the flavor, color and texture. Drain, squeeze out as much water as possible and set aside.

Slice the radishes and then cut the slices into matchsticks roughly the same size as the chives. Mix with the chives and keep on one side.

Season the fish on both sides. Heat 2 nonstick pans if you have them and put half the sunflower or vegetable oil into each. Add the fish, skin side down. When you put the fish in, it will arch upward from the first contact with the heat. Leave it for a minute or so to warm through, then slowly press the flesh down, from the tail end upward, so that all the skin is in contact with the pan and crisps up evenly. You will see some excess fat coming out of the fish between the flesh and the skin – so blot this up with some paper towels to help the skin to crisp up even more.

As the heat travels upward through the flesh, you will see it starts to turn white and opaque. When it is white almost to the top (probably only after about 2 ½ minutes in all), turn it over and then quickly take it out of the pan. Transfer to a warm tray or plate, flesh side down.

While the fish is cooking, put the spinach in a pan with the butter and warm through. Season and stir in the olive oil.

Spread the skin of the fish with the olive paste. Divide the spinach among 4 plates and spoon the balsamic dressing over. Place the fish on top. Season the radishes and chives and mix in the sesame oil. Arrange on top of the fish and serve.

Trancio di rombo liscio all’acquapazza

Acquapazza means “crazy water” – which is the way they describe the thin, watery sauce with tomatoes and olives in Napoli, where the dish comes from. I suppose the name is derived from the way the fishermen used to cook the fish on the shore, by taking a bit of water from the sea, crushing in a few tomatoes (you needed no salt, because it was already there in the seawater), boiling it up over a fire, then putting in the fish.

We make this dish with scarola, a crunchy Italian winter lettuce with a yellow heart – romaine lettuce is a good substitute. Usually in the restaurant we cook the brill on the bone – so if you can, ask your fishmonger to cut it into steaks, with the bone in, rather than fillets. If he has any extra brill bones, you can also make a very simple fish stock to use for the sauce, by putting them in a pan with some halved onion, chunks of carrot, celery, a handful of parsley stalks, a bay leaf and some peppercorns. Put in enough water to cover, bring to the boil, then turn down to a simmer, cook for 20 minutes and strain. If you don’t have the bones, or the time, just use water.

12 giant green olives, preferably Cerignola, with the pits

4 teaspoons sunflower or vegetable oil

4 skinless fillets of brill (or steaks, see above), each about 72 pound

1 wineglass of white wine

8 cherry tomatoes, halved

1 tablespoon tomato passata

2 garlic cloves, crushed

1 head romaine lettuce, separated into leaves

5 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

juice of 1 lemon

handful of chopped parsley

salt and pepper

Pit the olives, and cut them in half.

Heat 2 nonstick pans if you have them and divide the sunflower or vegetable oil between them. Season the fish and put into the pans. Fry on one side quite fast, so that they become nice and golden underneath (this will take about 3 minutes for fillets, about 6 if you are using steaks). Turn them over and immediately lift the fish out of the pans. Keep warm.

Divide the white wine between the two sauté pans and allow the alcohol to evaporate. Add half the tomatoes, then the passata and olives and a garlic clove to each pan and gently squash a couple of the tomato pieces. Add a ladleful of water (or, if you have made any fish stock as above, add this instead).

Let the sauce reduce for a minute or so, then put in the fish and gently heat it through.

Blanch the lettuce leaves in boiling salted water for 10 seconds – virtually just in and out – so that you keep the flavor, color and texture. Drain and toss the lettuce in a couple of tablespoons of the olive oil.

Arrange some lettuce in the middle of each of your serving plates. Lift the fish from the sauce and place on top. Mix together the 2 pans of sauce, add the lemon juice, parsley, and the remaining olive oil. Mix in and spoon over the fish.

Filetti di passera al basilico con patate e olive

Plaice is a fish I never saw in Italy, and here it seems very underrated – the ugly sister of the likes of sole – but it is fantastic when it is properly cooked. The problem with plaice is that because it is thin it is easily overcooked. Often people fry it in butter to crisp it up, but the butter burns, and everything tastes horrible. By cooking it in an herb crust you can turn the disadvantage of its thinness into a virtue, because you can get the crispiness without burning it, and the fish stays moist and protected inside. For the crust, we took some of the ingredients of pesto – including Parmesan, which goes against the rule of serving cheese and fish – and mixed them with some ciabatta, soaked in water, and bread crumbs. (In Italy, from north to south, everyone has bread crumbs in the kitchen – see page 436.)

2 bunches of basil, trimmed

bunch of parsley, trimmed

1 garlic clove

½ cup extra virgin olive oil 2 slices (4 ½ x 3 ¼ x ¾”) ciabatta, crust removed and soaked in water

1 tablespoon bread crumbs

1 tablespoon freshly grated Parmesan

8 new potatoes, unpeeled

4 tablespoons tomato passata

8 skinless plaice fillets, each about 5 ounces

12 black olives, preferably Tagiasche; buy them pit in, then take out the pit

4 teaspoons sunflower or vegetable oil

salt and pepper

Keeping back a few leaves, put the basil into a food processor with the parsley leaves, garlic and 4 teaspoons of the olive oil. Process until the herbs and garlic are chopped, but not too fine.

Squeeze the excess water from the bread and add to the herbs and oil. Add the bread crumbs and Parmesan and continue to process until you have a bright green paste. Put into the fridge until needed.

Put the unpeeled potatoes into cold salted water, bring to the boil, turn down the heat and cook until just tender (about 15 to 20 minutes), then drain.

Put the tomato passata into a small pan, season and add 2 tablespoons of the remaining olive oil. Leave over a low heat to reduce and thicken to a sauce-like consistency.

Peel the potatoes and cut in half.

On a clean work surface, lay out the plaice fillets and cut each one across in half. With a small table knife or spatula, spread each fillet with some herb paste, leaving a border all the way around the edge about ¼ inch wide. Cover with plastic wrap to avoid the crust darkening.

Heat a nonstick pan, put in a tablespoon of the remaining olive oil, add the potatoes and cook them until golden all over. Add the olives and toss for a minute or two – don’t let the olives get too dry. Turn off the heat.

Heat 2 more nonstick pans to medium-hot and divide the sunflower or vegetable oil between them. Lift each piece of fish and put it into the pan, crust side down. Season the flesh and let the fish cook until the crust becomes slightly golden and the borders of fish around it become completely golden.

Turn on the heat under the potatoes and olives. Add the reserved basil to the pan containing the tomato sauce.

When the fish has become white and opaque almost to the top, turn it over, then immediately take the pan off the heat.

Spoon the potatoes and olives onto each of your serving plates and drizzle the tomato sauce around. Lift the fish out of the pan, place on top of the potatoes and drizzle the rest of the olive oil over. Serve.

Pangrattato

“No one throws away bread”

From the north to the south of Italy, everyone uses bread crumbs. There is always bread in the house – no one eats a meal without it, and no one throws away bread, ever. My grandmother always had leftover bread drying by the oven. She would grate it (before the time of food processors) and store the crumbs in separate jars: one for fine crumbs, which would be used as a binder in polpette (meatballs), and one for thick crumbs, which might be mixed with herbs to make a crust in which to bake fish. Some bread crumbs she would put into the oven until they dried out but barely colored. These are the ones she would use to coat pieces of veal to make Scaloppina Milanese, and the toasted crumbs would add a nutty flavor and extra crunch.

Bread is our thickener: big chunks in soups, thick crumbs in stews, finer ones in sauces. We rarely use flour as a thickener in the way that other countries do (for example, in France they would make a roux with flour and butter; in Asia they might use corn flour). The only time I remember my grandmother doing something similar was when she browned some flour in the oven to thicken onion soup, which no doubt owed something to the classic French soup.

In the south of Italy, especially around Calabria, if they made pasta with olive oil, garlic, chile pepper and tomato, and it was too expensive to grate cheese over the top, they used bread crumbs.

We also use torn bread with the crust taken off, which we call mollica. It might be soaked in milk, wine, water or vinegar, according to the dish. In Toscana they make panzanella, with (unsalted) Tuscan bread that is a few days old. At its simplest, the bread is torn up and mixed with chopped tomatoes, onions and basil (though sometimes people will add some capers, or chopped cucumber, peppers or celery), tossed in vinaigrette, then left overnight in the fridge, so that all the flavors develop. We serve it with chargrilled sardines (see page 438).

Filetti di passera con castelfranco finocchi e bagna càôda

This is a very light dish but with a very full flavor. Normally, I prefer not to buy anchovies in oil because, unless you are sure of the quality, they can sit around too long and become rancid. Traditionally in Piemonte, however, they use them for this dish, so just try to buy good-quality ones. Alternatively, buy salted anchovies, soak them, pat dry and put them under oil yourself. In winter we use Castelfranco, a type of radicchio that looks like a yellow rose with red spots (see page 468), but you can use arugula instead.

8 skinless plaice fillets, each about 5 ounces

2 fennel bulbs

4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

3 garlic cloves

3 tablespoons milk

10 anchovy fillets in oil

4 teaspoons sunflower oil

1 head of Castelfranco radicchio (see above) or a large bunch of arugula

juice of 1 lemon

salt and pepper

Lay each plaice fillet between 2 sheets of plastic wrap and, with a meat pounder or rolling pin, very gently pound to make the fish thin enough to roll. Remove the plastic wrap, then carefully roll up each fillet into a cylinder, trim each end, and secure with a cocktail stick.

Cut the fennel bulbs in half lengthwise, then slice lengthwise again, fairly thickly – each slice should be around ¼ inch thick.

Heat a tablespoon of the olive oil, crush one of the garlic cloves and add to the pan, with the fennel. Cover with a lid, and stew gently for about 5 to 6 minutes, adding a little water if necessary. The fennel should be cooked but still slightly crunchy. Turn off the heat and leave to cool in the cooking liquid.

While the fennel is cooking, put the milk into a small pan with the rest of the garlic, bring to the boil, turn down to a simmer, and cook until the garlic is completely smashed (about 10 minutes).

While the garlic is cooking, put the anchovies into a small bowl over the top of the pan and stir to “dissolve” them – it will only take a few minutes. Push through a fine sieve.

When the garlic is cooked, hand-blend it with a little of the cooking milk. Add the anchovies and 2 tablespoons of the remaining olive oil.

Heat 2 nonstick pans and divide the sunflower oil between them. Season the fish rolls and put into the pans, each roll standing on its end. Cook for 2 minutes until the bases turn golden, then turn each roll over on to the other end, and cook for another 2 minutes. Turn the heat down and leave to rest for a minute or so in the pan, to cook through.

While the fish is resting, toss the Castelfranco or arugula with a mixture of lemon juice, the remaining olive oil and salt and pepper. Arrange in the middle of your serving plates with the fennel around it. Drizzle with the anchovy sauce, then place the fish on top of the salad.

Panzanella is a very old Tuscan tradition – a salad made with leftover bread, which would be unsalted, in the local style. It is a summer dish, which you would make when tomatoes and basil were good and plentiful. If you want to make it the day before you eat it, the flavors will have longer to infuse and it will taste even better.

When you cook the sardines, it is very important to get your griddle pan really hot; otherwise the sardines will stick and you won’t be able to turn them without breaking them up.

12 large sardines

5 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

For the panzanella:

7 ounces (about 7 slices 4 ½ x 3 ¼ x ¾”) stale Tuscan bread or ciabatta, without crusts, torn up

4 tablespoons white wine vinegar

3 tomatoes on the vine

1 large red onion, cut into ¾-inch dice

big bunch of basil

5 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

salt and pepper

First, get a griddle pan smoking hot; otherwise the sardines won’t release their fat and will stick to the pan.

To make the panzanella: soak the bread in the vinegar. Take the tomatoes from the vine, dice and add to the bread, together with the chopped onion. Tear the basil and add that too. Add the olive oil and season with salt and pepper. Stir together and set aside.

Scale and fillet the sardines (see page 94).

When all the sardines are prepared, season, brush with a little of the olive oil and put in the hot griddle, 6 at a time. Let them get crusty on one side (about 3 minutes), then turn over and do the same on the other side (about 2 minutes).

While the sardines are cooking, spoon some of the panzanella on each serving plate, then put the sardines on top, drizzle with the remaining olive oil and serve.

MY last year in Paris was traumatic, an experience I have virtually blanked out of my memory. At the Four d’Argent, we were expected to give everything, but got nothing back. At the end of service, even on Christmas Day. I would sit on a trash can eating two sausages, while people in the restaurant were paying half of what: I earned for a portion of spinach à la crème. It felt so unjust. I told myself that my own restaurant wouldn’t be this way. Your staff has to have quality in their lives. It is the people who make the restaurant, and if they are miserable, you have a miserable restaurant. After nearly a year, I woke up one morning and said: “That’s enough.”

I handed in my notice and, at first, the chef wouldn’t accept it. He gave me such a hard time about wanting to leave I felt even more pressured, but I told myself, “If you don’t want to work there, don’t do it, they can’t come hunting for you …” So I left and went back to Italy, totally depressed and unwell. I didn’t even know if I wanted to cook anymore. I was smoking a lot and barely eating. I weighed nothing, and I was coughing all the time.

My mother took me to the doctor, and she and my grandmother were so worried about me, they thought I was going to die. But I got back on my feet, put on some weight, borrowed some money from my brother and took off with my good friend Mario on our motorcycles to travel around Morocco and Spain. Mario was a big guy and he loved food, so eating and drinking were our priorities. His father was a wealthy man, and he saw our trip as a last chance for two young guys to have some fun before knuckling down to proper work, and so he kept sending us money.

We had a brilliant time, lost in a completely different world, totally free, just us, our bikes and the clothes on our backs. We were reinventing ourselves every day in a different place, stopping wherever we wanted, usually where we were drawn to somewhere selling simple and inspiring food. On the way home we stopped in Barcelona – what a place! We met some girls and staved on … so in the end the month we were supposed to be away had turned into nearly three.