“Into your last glass of white wine after luncheon slice a peeled yellow peach. Leave it a minute or two. Eat the peach and then drink the wine.”

Elizabeth David, Italian Food 1954

The rhythm of a traditional Italian meal, with its risotto or pasta course, has enough carbohydrate highs without needing anything elaborate to follow, so the typical Italian dessert repertoire tends to be more humble than that of other cultures. Actually. I love English desserts like sticky toffee pudding and bread and butter pudding, but not alter an Italian meal. Then all I really want is fruit, which in Italy is considered noble enough to be a dessert in itself.

Of course, every region has its cakes and pastries, but these are things we eat out, perhaps in the afternoon at the café or pasticceria (pastry shop), or keep for Sundays with all the family, or for special celebrations. Because we never miss the chance of a feast or a carnival, for every harvest or saint’s day or important occasion in the church calendar there will be something special – torta (cake), frittelle (fritters), biscotti (cookies), or a sweet such as torrone (nougat). Maybe it is just that Italians feel guilty about eating a dessert as well as three other courses, so we justify our favorite things by associating them with saints.

Perhaps the biggest festival of eating and drinking is the Panarda held in Abruzzo, most famously in the village of Villavallelonga. On the feast of Sant Antonio Abbate (abbate means “abbot”), on January 17, an incredible parade of anything from 30 to 50 dishes goes on all night, finishing up with pastries like fiadoni, little envelopes filled with fruit and ricotta. One of the legends – as ever. Italians can never agree on such things – is that a local woman went to draw some water, and when she came home, she found that a wolf had picked up her baby in his mouth. So she prayed for help from Saint Anthony. He was the founder of monasticism, a hermit who was supposed to be a great naturalist and protector of animals, and so the people of Villavallelonga would pray to him to help protect them against wolves. When the wolf let go of the baby, she made a big feast to say thank you to the saint.

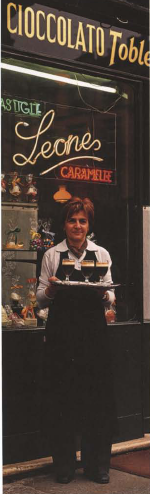

Italians are not ashamed to buy their desserts, so on Sunday mornings the family will go to church and on the way home stop off at a pastry shop like my uncle’s in Gallarate to buy a cake to take home and have after lunch. Going out for a pastry or an ice cream is also a social thing, so in the summer everyone might sit down and have a meal together in the evening, then go out for a walk and end up at the gelateria for an ice cream and a coffee. In America, the tradition is that the ice cream trucks come around and play tunes that appeal to the kids, but in Italy, it has always been considered a grown-up, civilized thing to go out for an ice cream. Sometimes the men will go to the bar or a social club, but the clever places are the ones that combine the bar and the gelateria, so everyone is happy.

At home, my father never finishes a meal without an apple, or whatever fruit is in season. Even if he goes out to a restaurant, that is what he asks for. In our house in Corgeno there is always a big fruit bowl in the kitchen and, if you were to come over for dinner, dessert might be just black and green grapes, in a bowl filled with water and ice. Though there is a school of thought that fruit at the end of the day creates too much acidity in the stomach, my family have all lived long lives eating fruit after dinner.

If you look at old menus and books, it is clear that fruit has always been significant in our religion and culture. We don’t talk about forbidden cakes, do we? The Romans were crazy about exotic fruits and brought them in from all over the world, so we have them to thank for cherries (though some people think they were already known in Italy), for peaches (which originated in China and were brought to Italy from Iran, or Persia as it was then) and for figs. Figs are so important in our history that the story is that Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Roma, were nursed by a she-wolf under a fig tree, which was later considered to be sacred. There is also an idea that the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden was originally a fig, and that much later the Catholic Church changed the story, because apples represented the evil fruit of the Romans who, like the druids before them, celebrated their pagan rituals and festivals by getting high on cider. I like to think of figs as the fruits of Paradise, and I like to serve them as simply as possible – perhaps just with some Mint sorbet (see page 560) and some fresh mint leaves.

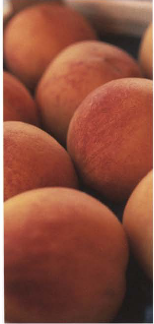

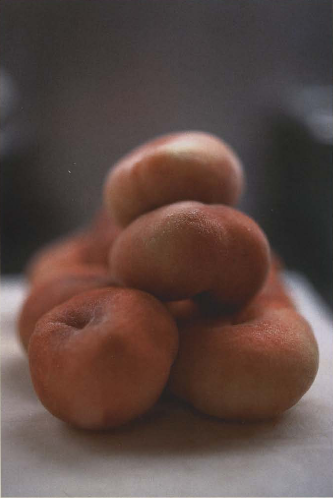

In Italy, because we love fruit so much, we have a great respect for its seasonality and locality. When you go to the market, the fruit there will have been grown in orchards and fields nearby, and because it is picked ripe, it must be sold by the end of the day, or it is wasted. You see the people touching and smelling everything, because a peach isn’t just a peach, a cherry isn’t just a cherry. If you have ever tasted and smelled a peach at that perfect point of ripeness, straight from the tree, you will understand that such a fruit is something beautiful, not just a commodity that can be grown anywhere in the world to the perfect size, shape, color and degree of fake ripeness that the supermarket demands. Fruit shouldn’t be harvested underripe, then kept chilled while it is transported so that it still has a “shelf life” of many more days, but never ripens to the same extent. What sort of mind games are being played with us, when we see these fruits that look ready but are hard enough to play tennis with?

Every fruit has a place in the year that seems to make sense, and that can be appreciated and looked forward to. When I was little everyone had vines, so there would be grapes in the autumn, and each year we would go to visit a friend of my granddad near Asti, famous for its Moscato Bianco (white Muscat) grapes, to have a big lunch and celebrate the start of the harvest. In the north, there is also a big production of pears, and there would be a special dispensation during the apple and pear harvest when the secondary school would close for a week, so everyone could help. I love pears – particularly small ones – possibly even more than peaches, especially the way you can fry them very fast with some sugar and they will be crunchy and colored on the outside, and on the inside soft, but granular, in their peculiar way. And I love the way pears work as generously when you add them to a savory’ dish as in a dessert. There is a famous saying in Italy, “Al contadino non far sapere quanto è buono il formaggio con le pere,” which translates roughly as: “Never tell the fanner how good a pear is with cheese” (or he will charge you more). And it is true: a hard, rich, salty cheese is perfect with a sweet pear after a meal – Parmesan in the north, pecorino farther south. Or it can be a meal in itself. I remember when I was little, seeing people going skiing, and instead of sandwiches, they would take a pear and a piece of Parmesan to eat up on the slopes.

Sometimes we also picked the fruit of the wild apple trees, which we called ranetta (little frogs) because their skins were so rough, like sandpaper. My grandmother would make them into frutta cotta (jam) for a crostata, a very thin, crispy base of pastry with the jam spread over it, or she would cook them with a little sugar and water to make a “fruit cheese’’ or paste, to eat with Parmesan after dinner. When the first oranges came in from Sicilia, you would see people filling big baskets at the markets, and when the cherries and peaches came into season there would be more excitement. In the summer, too, you would see guys selling pieces of watermelon in the street (in the country, they would often keep the melons cool in the river) because, when you are in the blistering sunshine, it is the right time to eat something so refreshing – not imported born South America and packed in baskets al Christmastime.

What relatively few recipes there are for fruit desserts throughout Italy are usually simple transformations incorporating local ingredients but preserving the shape and essence of the fruit, such as pere cotte al vino (pears poached in wine, see page 524), traditional in Piemonte, or pesche ripiene, peaches stuffed with almonds (and/or amaretti biscuits). Two of my favorite fruit desserts are actually French: Poire Belle Hélène, which I eat whenever I go to Paris in a café near l’Opéra, where they do it brilliantly – hot chocolate sauce, ice cream, pear … fantastic; and Peach Melba (see page 528), the most famous of all peach recipes. Both of them have a connection with opera. Poire Belle Hélène was supposed to have been created in Paris to celebrate the opening of the operetta by Offenbach about Helen of Troy, La Belle Hélène; and Peach Melba was created by the famous chef Auguste Escoffier in honor of the opera singer Dame Nellie Melba.

In Italy, the tradition of preserving seasonal food also applies to fruit. Especially in the south, where there is a massive production of citrus fruits, much of it goes into candied fruits and peel, a major ingredient in pastries and desserts. It must have been amazing 100 years ago to eat oranges, lemons and cherries in winter. If you go to shops in Sicilia, they have mountains of candied fruit in glass containers on the counter, which they scoop out for you. Sometimes they are whole, so you cut them up yourself.

Many of our celebratory cakes like panettone (our famous Christmas cake from Milano), pandoro (the Venetian answer to panettone) and panforte from Toscana travel all over the world and are considered “Italian”; other cakes are only famous locally – perhaps made in a particular village café or bar. In Varese in Lombardia, there is a bakery where they make a brilliant torta di Varese: a French-style sablé with nuts in it. Not far away in Gallarate, at the Bar Bianchi, they make their own specialty, torta del Bianchi, which is made with hazelnuts, almonds, eggs and flour, a little like frangipane, but very moist and crumbling at the same time. There are hundreds of different recipes, which might be as humble as pan tramvai (raisin bread, see page 158) or as elaborate as torta alla Milanese, a traditional pie filled with something like old-style English mincemeat: minced roast or stewed beef or veal, mixed with sugar, butter, chocolate, pine nuts, golden raisins and candied fruit.

Even though these days northern and southern Italians have moved around the country and are all mixed up, our cakes and pastries still reflect the way that, as with all Italian food, ideas varied from region to region, depending on local ingredients and influences. In the northeast, especially around Milano, Torino and Venezia, which are so close to the borders of Austria and Germany, you have a great excitement over patisserie, which you eat with coffee or hot chocolate in more bohemian Viennese- or Parisian-style cafés. Whereas in the south, around Palermo and Napoli, they also have fantastic pastries, but they have their place in the more multicultural bars: perhaps just one or two local pastries made in their own kitchens.

In the north you can see the mark of French and mid-European patisserie in the use of locally produced cream and butter, and puff pastry (pasta sfoglia). To make puff pastry successfully it needs to be kept cold, so in the days before refrigeration was available to everyone you would find this kind of rich pastry only in the north. In the hotter south, pastry made with pork fat (lard) was more normal. In Trentino-Alto Adige and Friuli-Venezia-Giulia, close to the border with Austria, Strudel is a typical thing, and at Easter time in Friuli they make a Strudel called presnitz, stuffed with candied fruit and spices. In 1891, in Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, Pellegrino Artusi included a recipe for Strudel, warning Italians in other regions, “Do not be alarmed if this dessert seems to you to be a strange concoction, or if it looks like some ugly creature such as a giant leech or a shapeless snake after you cook it; you will like the way it tastes.”

In the north, in addition to cream and butter, you see a great use of chestnuts (see page 576) and chestnut flour. Chestnuts were an important staple for people during the war, and typical desserts are castagnoli con crema (fritters filled with chestnut cream), castagnaccio (a cake made with chestnut flour, often with golden raisins, walnuts and pine nuts added, and sometimes topped with rosemary) and torta di pasta alle castagne (pasta made with chestnut flour, cooked in a syrup and pressed and set hard into a solid cake, which is very, very good). Since “light” is not a word we use often in the north, you find all kinds of torte di tagliatelle, and also torte di riso (rice cakes), which reflect our love affair with rice.

Further north, in the Valle d’Aosta, they are famous for montebianco, named after the highest mountain of the Alps: chestnuts cooked with milk, sugar and vanilla, then puréed, flavored with rum, piled up to look like a mountain, and chilled. Before serving, the “mountain” is smothered in whipped cream to look like a snowy peak. In Piemonte, they are also known for pannacotta, which literally means “cooked cream,” and another important dessert is the bonèt, which is made with amaretti cookies, eggs, sugar, cream, cocoa and rum in a bain-marie, and served cold. One story is that it is called bonèt because the bain-marie it is made in looks like a hat; other people say that because it was served at the end of a meal, it was called after the hat your friends would put on to go home afterward. Or, I think, because of the local French influence, it could be that it just means the “very good” dessert. Tiramisù (see page 554), which means literally “pick-me-up,” is one of our most loved northern desserts, though it isn’t a traditional recipe at all. It is supposed to have been invented by a restaurateur in Treviso in Veneto in the sixties.

After such excitement over patisserie in the north, as you work down the regions, traditionally desserts become a little boring. Toscana, for example, a region that has produced some of the great classics of Italian cooking, and contributed so much to shaping the idea of Italian food all over the world, is quite poor on desserts. And what there is, like the medieval panforte, tends to be visually a little on the brown side, like the distinctive colors of the land around.

In Abruzzo, they go for cakes like the parrozzo, made with almonds and covered with chocolate. Its name, which comes from pan rozzo, the local round country bread, was given to it by the poet D’Annunzio, who was a friend of the cake maker who created it. Then, when you reach the south, what amazes me about the desserts is that, though you might expect them to be refreshing because of the heat, apart from the gelati (ice cream) and sorbetti (sorbets), in fact they are very sugary and rich, often filled with ricotta (which replaces the mascarpone of the north), candied fruits and nuts. In Napoli you find the Easter pastiera, an elaborate tart of sweet pastry (pasta frolla) spread with ricotta, candied fruits and spices, topped with a lattice of more pastry and baked (see page 548 ). Napoli is also the home of rum baba, which is supposed to have been created by King Stanislao Leszczynsky of Poland, who was the father-in-law of Louis XV of France. While he was exiled in Lorraine, he used to soak stale kugelhupf, the local cake, in rum, and he called his concoction the Ali Baba, because he loved to read The Arabian Nights. When the house of Bourbon took over Napoli, the dessert came too, but just became known as baba.

Sardegna is famous for its honey desserts, and you can see the influence of the Arab invasion in regions like Calabria and Sicilia, where candied fruit figures in many of the local desserts, such as cannoli (see page 545), the famous pastry tubes (made with pork fat) flavored with cocoa, then fried and filled with sweetened ricotta, candied peel, pistachio nuts and pieces of chocolate. Or cassata, a complicated cake made again with ricotta, vanilla, chocolate and candied peel, covered with almond paste and decorated with more candied fruit. Cassata gelata is an iced dessert with similar flavors, which we used to make at Zafferano.

In the south they also play a lot with sweet-and-sour flavors, so you might find desserts made with eggplants and chocolate. In Sicilia, they have their own typical pastries, such as sfogliatelle, sheets of puff pastry, again made with lard, which are rolled up, then shaped around a filling of cooked semolina, ricotta and candied fruits, so that when they are baked they look like clamshells. Like many of our traditional pastries, they were initially made by monks and nuns. Apparently, sfogliatelle were first made in the eighteenth century for guests at the monastery of Croce di Lucca, but they were made famous much later by an innkeeper, Pasquale Pintauro, who prepared them fresh throughout the day, and they were so good, people lined up for them all the way down the streets.

Sicilians also make spectacular use of sculpted almond paste or marzipan (pasta reale). They are crazy about it. When you go into the pastry shops, you find dramatic, kitsch displays of marzipan shapes, which make you want to laugh sometimes. When we go on vacation to Sicilia, even in the villages in the middle of nowhere – so remote and hot, that if there is a puff of wind, the dry branches go rolling down the street as if in a spaghetti western – you can have three coffees in the morning at three different pastry shops, and each shop will be full of different elaborate creations.

Frittelle – fritters, which are more often sweet than savory – are something we have in common from the north to the south of Italy. My grandmother never made cakes, but she would make chiacchiere, which were fried pieces of sweet lard pastry. Usually she made them when we had fish to fry for dinner. She would put a big pot of clean oil on the stove first, and cook the chiacchiere, and then afterward put the fish into the same oil. At one time not everybody had ovens, so frittelle were easy to make, especially for many people in the village square, or at stalls on city streets for festivals or at carnevale. Personally, though I don’t think deep-fried food is generally a good idea, these things are so pleasurable, you just have to forget about what is good for you for a little while.

Every village, town or city has its festa or sagra. The festa is a saint’s day or a national holiday, whereas the sagra is dedicated to an ingredient, or celebrates a local harvest, such as the Sagra del Miele (honey festival) in Sardegna, the Lazio strawberry festival in June, or the Sagra del Dolci Eoliani (festival of typical Aeolian island sweets). At this last, the pasticceria are full of things like piparelli, made with honey, almonds, vanilla and spice, for dipping into the local Malvasia wine; and nacatuli, which are pasta parcels with a filling made with almonds, vanilla, cinnamon and tangerine juice. When I was young, I remember all the stalls being set up in the villages dedicated to different ways to cook and eat whatever ingredient was being celebrated, whether it was pumpkin or honey. In small communities, the festivities would often be around the church; and there would be music and dancing.

Often the feste celebrate very local historical events or saints. Since every saint seems to have his own frittelle, and virtually every day of the year is a different saint’s day, you can imagine how many different frittelle are made all over Italy. Some festivals are celebrated throughout Italy – though, even so, each community will have its own particular cakes, fritters, sweets and biscuits. Carnevale, for example, begins on January 17 and ends on Ash Wednesday, and all the kids have parties at school, so this is a time when the mothers all make special frittelle and they are all looking at each others’, thinking, “mine is better than yours.” In Lombardia, we celebrate with special chiacchiere di carnevale, sweet fritters, flavored with Marsala and dusted with sugar; while in Venezia they have galani, flavored again with Marsala or grappa, but made in the shape of a bow.

On March 19 Italians celebrate the Feast of San Giuseppe (St. Joseph), which is our Father’s Day, and, if you were in Bologna, the pasticceria would be full of ravioli di San Giuseppe, fried sweet pastries filled with jam or almond paste; in Napoli you would find zeppole di San Giuseppe, cream-filled rings of dough, which are fried for you on the streets and decorated with flowers and branches, and in Sicilia, sfingi di San Giuseppe, shells of puff pastry filled with ricotta and lemon and orange zest.

In Lombardia, on October 4, we celebrate the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, who looked after the animals, with mostaccioli, a special cake made with almonds, honey, sugar, spices, vanilla and sometimes orange peel. They say this cake is the only earthly food that St. Francis loved, and he is supposed to have asked for it on his deathbed. At Easter time we have our own special Easter cake, colomba pasquale, which is similar to panettone but made in the shape of a dove, covered with sugar crystals and almonds. Sometimes we serve it a bit like the French pain perdu (French toast), sliced and fried in butter, with ice cream. One of the things I remember most when I was growing up was the pan dei morti, a soft, dry kind of bread, made dark with chocolate, I suppose to signify death, which we eat on Il Giorno dei Morti (the Day of the Dead) on November 2. This is the day when everyone goes to the cemetery to lay flowers on the graves of family and friends; then we remember them and celebrate their lives with big feasts and parties. In other regions they have fave del morti, biscuits made in the shape of black fava beans, which, according to Pellegrino Artusi, were offered to the Fates, Pluto and Persephone, at the gates of Hell, because the beans were believed to contain the souls of the dead.

November 11 is another significant day, the Feast of St. Martino, which marks the end of the season of harvesting and preserving for the winter months, and also the first tasting of the new season’s wine, vino novello, which is often celebrated in festivals along with roasted chestnuts. St. Martino is said to be the protector of drunks, since he cut his cape in half and gave one half to a drunken man on a freezing night, and special biscuits are made to different recipes all over the country. Some of the most interesting are the Venetian biscuits, which are shaped like the saint on horseback.

Christmas, of course, is one of the biggest times for all kinds of traditional sweets, featuring local ingredients. Napoli is famous for its festive struffoli – fried dough balls dipped in a syrup of honey, spices and candied peel, then piled up all together in the shape of a wreath, and sprinkled with diavolilli, colored candied almonds. In Liguria, they make fried ravioli, stuffed with marrow, candied pumpkin and citrus peels; in Basilicata, sweet panzerotti, which are sweet ravioli filled with pureed chickpeas, chocolate and cinnamon; and in Sardegna their fried ravioli are filled with fresh pecorino and covered with honey.

The other things Italians have a big love affair with are biscotti (biscuits or cookies) – the word comes from the Medieval Latin biscotus, meaning “twice cooked.” I sometimes wonder when do we eat all these cookies? We must have hundreds of different recipes around the country. In the north, many biscuits became fashionable as Torino was a big center of commerce (and later in the nineteenth century, the capital of all Italy), so in the afternoons the merchants would break for tea or hot chocolate.

At the Venier pastry and coffee shop in Torino you can still see big cabinets filled with little cookies made by the chef Luciano to traditional Piedmontese and Campagnola recipes.

In Toscana, it is a custom to dip almond cantucci biscotti into the sweet wine, vin santo, and all over Italy, biscuits like savoiardi (ladyfingers) will be served with ice cream or creamy desserts. In any one region, you might have 25 different biscotti recipes, which, like those for our cakes, are mostly all variations on the same ingredients – nuts (almonds or hazelnuts), sugar and golden raisins. These range from the famous almond macaroons, amaretti, from my region of Lombardia, to ricciarelli, the typical almond and honey cookie of Siena, flavored with orange zest, spicy spezzatini or pepatelli, made with black pepper, both typical of Toscana, baci di dama (lady’s kisses), to which chocolate is added, and Umbrian pinoccate, cookies made with pine nuts.

Pellegrino Artusi even includes a recipe for cookies for “birthing mothers’’ that were supposed to be eaten with a spoon and were made with sugar, vanilla sugar, cocoa powder, butter and egg yolks. The recipe was given to him by a lady from Conegliano, and she considered the results “nourishing and delicate, just the thing for restoring the strength of women who have grown weak bringing a baby into the world.”

Then there is a big fight with the French over who invented savoiardi (savoyarde) biscotti – these are the sponge fingers often served with ice cream and traditionally used in tiramisù. The French say they created them in Yenne in the Savoy region, but in Italy people say they were first made in Torino in around 1348 for Amadeus VI of Savoy, who was called Il Conte Verde, the Green Count, because he and his ensign always wore green. Since Torino first came under the control of the French house of Savoy in the thirteenth century, who really knows who influenced whom?

At Locanda, it is hard to put a simple fruit salad on the menu, or the kind of typical tarts or cakes we used to make at Olivo, because most people who come to eat consider a more complex dessert to be a highlight of a restaurant meal. And, anyway, Plaxy wouldn’t allow me to have a dessert menu without at least one chocolate dish on it. On the other hand, especially at lunchtime, we find that people want something light and easy to digest, and then, like Italians, they lean toward fruit, as long as it is presented in an interesting way, with some extra elements and different textures. So what we do is follow the same philosophy as for the rest of the kitchen, and take another look at the typical regional cakes, cookies, ice creams and combinations of fruit that all Italians know and understand, then rework them, give them a new twist, or bring together four or five different ideas on one plate; so we keep the spirit of Italian desserts, but with respect for the different appetites of our customers.

Every major restaurant kitchen has a pastry chef who is in charge of his own section, and concentrates only on the desserts. While I don’t like to see complicated presentation in our starters and main courses, I feel that you have to let pastry chefs spread their wings and fly. Antonio Carluccio once said to me that when you get to the dessert course at Locanda it is almost like going to another restaurant – but I am happy with that, because it means our desserts are a talking point.

Pastry chefs are a different breed from the rest of us in the kitchen. When you are working at the stoves, of course you do as much of the preparation as possible in advance, but when someone orders a piece of fish, you must cook it for them then and there, and it is all about speed, immediacy and spontaneity – no two fish are ever exactly the same; there is always an edge of unpredictability. And if you overwork and fuss over the garnishes and sauces, it is an obstacle to the quality of the finished dish, which gets confused and colder the more you meddle with it.

When you work on the pastry section, though, it is exactly the opposite. Everything is about thinking, planning, weighing, measuring and preparing, quietly and meticulously, so that all the elements look – as well as taste – beautiful, and only need to be assembled at the last moment. And once you have designed a dish the way you want it, that is it – you can repeat it again and again, and it should always be perfect.

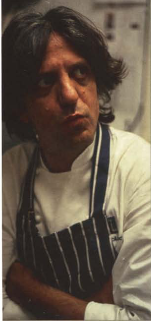

Personally, I never liked working on the pastry section much; I am too impatient. I like to work with handfuls of parsley, not spend my time weighing out every crystal of sugar or every gram of cream – which is what you must do to ensure that the chemistry works. Of course I have my ideas and my opinions, and I taste everything and sometimes, when the boys on the pastry get too carried away, I tell them that all that chocolate and vanilla must have gone to their brains and made them crazy. But we are lucky in that we have had two brilliantly creative pastry chefs at Locanda, who have given a real sense of excitement to what we do. In the beginning, it was Damian Allsop, who was in charge of the pastry and who first came up with all sorts of dramatic desserts. Then he went off to work with the Italian chocolate maker Amedei, and Ivan Icra took over. Ivan is Catalan, from Barcelona, which is a hotbed of new ideas in cooking, and especially desserts. In Barcelona, one of the most talked-about restaurants is Espai Sucre (sugar space), where the whole menu is devoted to desserts. Ivan is one of a new wave of pastry chefs who is excited and influenced by the brilliant Spanish chef Ferran Adrià at El Bulli, with his way of questioning and deconstructing dishes, and building up different textures with jellies and foams – which are easy to do at home; you just need the kind of chargeable siphon you can buy for whipping cream.

Of course, Catalunya is culturally quite close to Italy, because it was once a principality of Aragon, and the Aragonese invaded northern Italy in the fifteenth century. In Alghero, the northern city of Sardegna, which was part of the Catalan kingdom for more than 400 years, many people still speak Catalan, and you find Catalan food in the restaurants. We share a love of many of the same ingredients, like tomatoes and almonds, and we all treasure our special dishes for festival days – so our ideas are very much in sympathy. Though, of course, that doesn’t stop the constant Catalan versus Italian banter that goes on in the kitchen.

As always, though, what we do in the restaurant and what I would do at home are two different things. At home, I wouldn’t make a cake and ice cream and cookies, and a foam and a sauce, all for one dessert. I also think it is important that, if you have cooked a meal for six people, you don’t kill yourself over the pudding; so unless you are feeling ambitious or you really, really love making desserts, you don’t need to do all the elements that we bring together at the restaurant. Maybe just make a cake or a tart, or poach some peaches or pears, and, if you like, you can buy some good ice cream to serve alongside. Or just make an ice cream, and perhaps a cookie. It’s up to you.

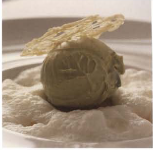

Sorbetto di melone, fragole selvatiche, salsa all’arancio

1 pint wild strawberries

For the orange sauce:

1 cup fresh orange juice

⅓ cup superfine sugar

To serve:

Melon sorbet (see page 560)

When wild strawberries are in season, we serve them with melon sorbet and orange sauce. To make the sauce, simmer the fresh orange juice with the superfine sugar, until you have a spooning consistency, then leave to cool. Arrange the wild strawberries in the center of your plates. Put a scoop of melon sorbet on top of the strawberries and spoon some of the orange sauce around. If you like, you can garnish the sorbet with Melon crisps (see page 581).

This is a lovely fresh dessert that might sound complicated but is actually very straightforward – and the advantage is that you make it the day before you want to serve it. We first made it by chance, really. We have some friends who have a farm near Mumbai in India, and we always give them some seeds of things like arugula to experiment with and, in return, when they visit us they bring us some fruit. One year they came over with about five boxes of mangoes – what were we going to do with them? At the time, we were searching for different ways of serving fruit for the lunchtime menu, and so we came up with this idea of a “fruit lasagne” – layers of fruit, which are pressed. We serve it with a scoop of vanilla ice cream (or sometimes Amaretto ice cream; see page 564) on top of a square of caramel sponge (though if you like, you could substitute a sweet cookie). For this recipe, you need two plastic containers of the same size, roughly 6 x 4 ½ inches and about 2 ½ inches deep.

4 ripe mangoes

14 ounces (about 2 ½ cups) strawberries

For the caramel sponge:

1 ¼ cups tin of condensed milk

⅔ cup (3 large eggs) beaten eggs

¾ cup flour

1 heaping teaspoon baking powder

½ cup butter

2 tablespoons golden syrup

pinch of mixed spices, such as ground cinnamon, cloves, star anise (optional)

a little flour and butter for preparing the baking dish

To serve:

Vanilla ice cream (see page 561)

4 Candied vanilla beans (optional, see page 583)

The day before you want to serve the lasagne, peel the mangoes and slice very thin. Wash, hull and dry the strawberries and slice them lengthwise, just slightly thicker than the mangoes. Keep the trimmings from around the mango stones and blend these with a hand blender to make a smooth puree. Keep in the fridge.

Line one of the two containers with plastic wrap, enough to come over the sides.

Line the base with about a fifth of the mango slices, making sure there are no gaps between the pieces (when it is turned out, this will be the top layer of your “lasagne”). Next, make a layer of strawberries, using about a quarter of the slices. Repeat the layering three more times and finish with a layer of mango slices.

Cover with a large sheet of plastic wrap – again big enough to overhang the sides. Have a flat plate or tray ready that is big enough to put the containers on top of one another, and fit into the fridge. Put the second container on top of the first, hold firmly and flip the two containers over together onto the tray. Put a weight on top (a milk bottle or some cans will do). The idea is that the excess juices from the fruit will drain out onto the tray, so cut away the excess plastic wrap, so that it doesn’t get in the way. Put in the fridge for 12 hours.

To make the sponge, first make a caramel, see page 522.

Preheat the oven to 300°F, grease a rectangular baking dish with butter and dust it with flour.

Whisk the caramel with the rest of the sponge ingredients until you have a smooth mixture. Pour the mixture into the prepared baking dish and bake for 25 minutes, until springy to the touch and a sharp knife inserted in the center comes out dry (if it is moist, keep the sponge in the oven for a little longer).

Turn the sponge out on to a cooling rack and leave to cool, then cut into squares.

When ready to serve the lasagne, take off the weights and remove it from the fridge. Turn the two containers back over together and remove the top one. Put a chopping board over the top of the remaining container and, holding it firmly, turn both board and container over together, so that you turn out the lasagne on to the board. Trim the edges if necessary, cut it into 4 and place a square on each of 4 plates.

If you have a kitchen blowtorch, dust the top of each slab of lasagne with sugar and glaze it quickly with the torch.

Scoop some ice cream on top of each square of sponge, spoon the reserved mango puree around and garnish with strips of candied vanilla pod, if using them.

For this kind of caramel, which we use in lots of desserts, we have a trick that is famous in South America and used in things like banoffee pie.

All we do is put a can of condensed milk into a pan of boiling water and let it simmer away for about 3 to 3 ½ hours, topping up with more water if necessary.

The sugar in the milk caramelizes and when you take out the can (carefully) and open it, you will find a thick, dark toffee, known as dulce de leche, which is much more dense than you could easily make with whipping cream and sugar – and much easier.

The toffee makes a wonderful “glue,” if for example we want to stick a cookie or a piece of pineapple to a plate, so that it doesn’t slide when the waiter carries it - such considerations are very important in a restaurant!

Pere cotte al vino rosso e bianco

We had a big pear tree in our garden in Corgeno and, in the season, we had pears coming out of our ears, so my grandmother often used to poach them in wine. We add some spices and, when we serve them, we go to town a bit, building up different flavors and textures to set off the fruit, with various sorbets and ice creams and cookies. However, you can serve the pears very simply with vanilla ice cream, and, if you like, some sweet biscuits, such as Sablé (see page 578).

4 medium-sized ripe pears

1 ¼ cups white wine

½ cup superfine sugar

2 cloves

2 cardamom pods

1 ¼ cups red wine

1 cinnamon stick

1 star anise

To serve (optional):

Vanilla ice cream and cookies, such as sablé (to make your own, see pages 561 and 578)

Or:

8 Frangipane wafers, in rounds (see page 575)

4 Frangipane wafers, twisted into balls (see page 575)

Mascarpone ice cream (see page 562)

Cinnamon ice cream (see page 569)

Peel the pears and cut them in half, remove the cores, then cut each half lengthwise into thirds.

Put half the pear pieces in a pan with the white wine, half the sugar, the cloves and cardamom pods. Put the rest of the pear pieces in another pan with the red wine, the rest of the sugar, the cinnamon and star anise.

Heat both pans very, very slowly on as low a heat as possible for around 10 minutes – the wine shouldn’t even reach a simmer, as you want to cook the pears through, without their falling apart. When the wine begins to get hot, test the pears with a sharp knife. If it slides into the pears easily, they are ready. Take off the heat and leave to cool.

Lift out the pears (keeping them separate), then boil up each liquid separately (to 250°F, if you have a thermometer) and reduce to a thick syrup – remembering that it will thicken more when it is cold. To check if it is the right consistency, put a spoonful on top of a piece of marble or a cold plate – within seconds it will be cold. If it is watery, it needs to be boiled for a little longer, but if it spreads a little but holds its shape, it is ready.

Serve 3 pieces of each type of poached pear in each bowl, with vanilla ice cream, drizzled with the two different colored syrups, and cookies. Or, if you want to be more elaborate, arrange the two pears separately on plates, drizzled with their respective sauces, together with 2 rounds of frangipane wafers on each plate. Top one cookie with mascarpone ice cream, the other with cinnamon ice cream, and garnish with frangipane wafers.

Pere cotte e crude con zabaione a moscato

If possible, use organic, free-range eggs (we use Italian eggs, the yolks of which are very deep orange-yellow); and try to find really juicy pears. The ones we use are Italian Forelle, which are very beautiful, small and juicy, with a fantastic yellow and crimson skin.

4 pears

¾ cup plus 1 tablespoon Moscato wine

superfine sugar, for dusting

¼ pound puff pastry

For the zabaglione:

8 egg yolks

¾ cup Moscato wine

3 ¼ tablespoons superfine sugar

Preheat the oven to 250°F.

To make the confit, cut two of the pears into dice (about ¼ inch) and put in a pan with the Muscat wine. Cook very slowly until the pear is soft. Leave to cool.

Dust a work surface with superfine sugar and roll out the pastry as thin as you can, sprinkling with more sugar as you go, then cut it into strips about ¼ inch wide (you need 2 or 3 per person), and twist them like loose corkscrews.

Lay the strips of pastry on a baking sheet and put into the oven for 4 to 6 minutes, or until golden. Leave to cool.

Peel the remaining pears, slice them very thin, preferably on a mandoline grater, and keep to one side.

To make the zabaglione, bring a pan of water to a boil and turn down the heat. Put the egg yolks, Muscat wine and sugar into a round-bottomed bowl, start to whisk a little, then put the bowl over the pan of water and continue whisking until you can form a figure eight with the mixture that will hold for a few moments.

Lift the confit pears into a fine sieve and drain off the juice (you could chill it and serve it as a drink, mixed with Prosecco).

Arrange some of the drained pear dice in each of four bowls, then spoon some zabaglione on top. Arrange the slices of fresh pear around the outside, and crisscross the strips of puff pastry over the top.

“Such beautiful, sensual fruits, aren’t they?”

All Italians grow up with a love of peaches, which arrived from China in Roman times via Persia (now Iran), and we have a great respect for their seasonality and locality: the relationship of a particular variety to its native climate and territory. Most of the fruit on sale is grown locally, and the variety among peaches is amazing. The white peaches of the north are probably the most famous. These are the ones we bake stuffed with amaretti, and that are used in the Bellini, the famous drink “invented” in Harry’s Bar in Venezia. (I am sure someone, somewhere made such a drink before – how could you not put two such marvelous ingredients together?)

Nothing compares to a peach plucked straight from the tree – they’re such beautiful, sensual fruits, aren’t they? I love to take the kids to pick them, and see them growing in their natural surroundings. Near Corgeno, next to Lake Monate, there is a consortium that grows Pesche del Lago di Monate: very small trees, hundreds of years old, with each tree giving around 25 to 30 peaches – gorgeous, juicy yellow ones with a quite firm texture, which you can buy from stalls on the roadside.

One of the best peach desserts I have ever eaten was not in Italy at all but Anton Edelmann’s peach melba at the Savoy. It is a dish that generally has a bad reputation in England, since it is often made with canned fruit and ice cream, but the version at the Savoy, served inside a caramel cage, was a complex, perfectly balanced mix of crunch and gorgeous fruit. There they made it with white peaches, but I love to do it with the Pesche del Lago di Monate, because the slight crunch of the peaches is fantastic with the softness of the ice cream. First, you make a tuile basket for each person (see page 574) and some raspberry sauce. For four people you need to puree 10 ½ ounces (about 1 ⅓ pints) raspberries in a blender, add 2 teaspoons lemon juice and 4 ¼ tablespoons confectioner’s sugar, and put the sauce through a fine sieve. Set aside while you poach 4 whole peaches in sugar syrup for about a minute, or until the skin comes off easily, then peel them, let them cool, cut in half and remove the pits. Now you need to make your caramel cage. Mix 1 ¼ cups superfine sugar with ⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon water and 1 ½ teaspoons corn syrup in a pan, and put it on high heat. Brush the sides of the pan with water regularly to prevent the sugars from crystallizing, and cook to “hard crack” stage (300°F on a candy thermometer). Leave to cool until the syrup becomes thick.

Oil the outside of the bowl of a 4-inch-diameter ladle and lay it (round side facing upward) on your work surface. Dip 2 forks into the syrup and pull fine threads of it over the ladle in opposite directions to give a lattice effect. Finish with a thin line of syrup around the edge of the ladle to form the base of the cage. As soon as the syrup cools, carefully remove the cage from the ladle and keep it somewhere cool and dry. Repeat for 3 more cages.

To serve, pour a little of the raspberry sauce onto 4 plates, place a tuile basket in the center, scoop in some vanilla ice cream, top with a peach half, then spoon over a little more sauce. Carefully put a sugar cage over the top.

Spun sugar might seem a bit “eighties’’ now, but I have never thought of this dessert as at all pretentious, and I have never found a better way to serve peaches. All of us in the kitchen at the Savoy were so in love with this dessert – we were always trying to get the pastry cooks to let us have one. When I was in Paris and came back to London for a visit, I went to the Savoy to eat, and when they asked what I wanted, I said. “I don’t care, as long as I have a peach melba.”

Pesche sciroppate, semifreddo di menta e gelatina d’Amaretto

To make the molds for the nougat glace we use clear PVC tape (6cm wide), which you can buy in specialty kitchen shops. We roll it into cylinders about 1 ¼ inches in diameter, secure with tape, then put these inside small pastry cutters of the same size to hold them steady. Alternatively, you could use 4 flexible molds around 2 ½ inches tall and 1 ¼ inches in diameter – or even use a deep ice cube tray and give everyone 3 cubes each.

3 firm but ripe peaches

1 ¾ cups superfine sugar

½ cinnamon stick

1 star anise

8 mint leaves, to garnish

For the nougat glace:

¾ cup plus 1 tablespoon whipping cream

1 bunch (about 1 ounce) fresh mint

whites of 3 large eggs

¼ cup superfine sugar

For the Amaretto jelly:

1 ½ ounces water

2g gelatine leaves, soaked in water and squeezed

3 tablespoons plus 1 tablespoon Amaretto liqueur

For the ginger custard:

¼ cup egg yolks (from about 3 large eggs)

¼ teaspoon ground ginger

2 ½ tablespoons superfine sugar

½ cup milk

½ cup whipping cream

The day before you want to make this dessert, put the whipping cream for the nougat glace into a pan with the fresh mint and heat until it starts to steam (175°F if you have a thermometer). Take off the heat, allow to cool and put in the fridge for a day to let the flavor infuse.

Take the cream and mint mixture from the fridge and pass through a fine sieve, pressing the mint leaves down to extract the maximum flavor. Put into a mixer and whip until it makes firm peaks, then transfer to a bowl.

Clean the bowl of the mixer thoroughly, then put in the egg whites and whisk until they start to foam and white bubbles appear around the bowl. Very slowly, add the sugar, whisking continually until the mixture makes stiff peaks. Stop the machine and carefully fold in the reserved mint cream, keeping as much air inside the mixture as possible. Spoon the mixture into the molds (as described above), smoothing the top. Put into the freezer for at least 4 hours.

To poach the peaches, cut them in half, leaving the skin on, and remove the pits, then cut each into 4 segments. Put the sugar, cinnamon and star anise into a pan with 2 cups water, add the peach pieces and heat very, very slowly on as low a heat as possible for around 10 minutes – the wine shouldn’t even reach a simmer, as you want to cook the fruit through without its falling apart. When the wine begins to get hot, test the peaches with a sharp knife. If it slides into the flesh easily, they are ready. Take off the heat and leave to cool.

To make the Amaretto jelly warm the water in a pan and melt the gelatin into it. Stir in the Amaretto and pour into a bowl. Put into the fridge for around an hour to set.

To make the ginger custard, put the egg yolks, ginger and sugar into a bowl with 1 ¾ tablespoons of the milk. Put the rest of the milk and cream in a pan on the burner, and when almost boiling add the egg yolk mixture and cook (at 185°F if you have a thermometer) until thick enough to coat the back of a wooden spoon.

It should leave a clean mark if you run your finger across it. If not, cook it a little longer. Take off the heat and leave to cool. Lay a piece of plastic wrap over the surface to stop a skin from forming and put into the fridge until you need it.

To serve, spoon some custard on to each of 4 plates, take your cylinders of nougat glace from the freezer and arrange 2 per person on top of the custard. Put a mint leaf on top of each – it will stick to the cream. Lift the peaches from their juice, and arrange alongside, together with scoops of the Amaretto jelly.

Macedonia di nespole e sanguinelle, gelatina di violetta e schiuma allo yogurt

This is a fresh, colorful salad of fruit that is easy to make – you just need a half-liter (2-cup) siphon (the kind used for whipping cream) to make the foam.

8 fresh loquats, peeled and put into a bowl of water with a few drops of lemon juice, to keep the color

8 blood oranges, peeled and separated into segments

For the violet jelly:

2 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon superfine sugar

½ cup plus 1 tablesoon water

violet coloring, optional

violet essence, to taste

2g gelatine leaves

For the yogurt foam:

⅓ cup whipping cream

scant ½ cup superfine sugar

1 gelatin leaf, soaked in water

345g plain yogurt

0.5-liter (2-cup) siphon, plus 1 charge

To make the violet jelly, put the sugar in a pan with the water and bring to the boil. Take off the heat and add the coloring, if using.

When cold, add the violet essence to taste. Put a little of the mixture into a pan and heat gently. Add the gelatin, let it dissolve, then add to the rest of mixture and stir. Pour into a deep container and put into the fridge for 1 to 2 hours until set.

To make the foam, put the cream and sugar in a pan and heat until the sugar has dissolved. Take off the heat and add the gelatin. When it has dissolved, add to the yogurt and mix together. Pass through a fine sieve, and put into the siphon. Charge and put into the fridge for 2 hours.

Serve in deep plates or bowls: arrange the loquats and blood orange segments around the outside, with a square of jelly in the center and the foam on top.

I don’t want to give this an Italian name, because it is a dish that arrived with Ivan and is based on a recipe by Albert Adrià, brother of Ferran Adrià of El Bulli, who runs the restaurant’s famous laboratory in Barcelona. For me, a chef who is trying to impress, and be creative, will always be happiest when he works with ideas and ingredients that he understands – just as when you cook at home, you are always most comfortable when you cook something you know for friends rather than trying something new for the first time. So, of course, the idea of reinventing the famous crème Catalan dessert was quite natural; and we are very proud of it, because what was quite a thick creamy dessert is now transformed into something light and frothy, yet the essence and the recognizable taste are still there. And, you know, in reality I could call this a Milanese cream foam, because the ingredients, the flavor, the creaminess, everything about it chimes with the spirit of Lombardia.

1 pint mixed berries (strawberries, raspberries, blueberries, etc.)

8 tuile biscuits (to make your own, see page 574)

Crème Catalan ice cream (see page 561)

For the Catalan cream foam:

¾ cup whipping cream

¾ cup milk

½ vanilla bean

½ cinnamon stick

peel of ½ orange

peel of ½ lemon

yolks from 4 large eggs

2 heaping teaspoons cornstarch

¼ cup superfine sugar, plus extra to caramelize

0.5-liter (2-cup) siphon, plus 1 charge

First make the Catalan cream foam: put the cream and milk in a pan with the vanilla bean, cinnamon stick and the orange and lemon peel. Bring to a boil. Take from the heat and leave for 30 minutes to infuse. Pass through a fine sieve.

Put the egg yolks, cornstarch and sugar into a bowl and whisk together, then add ¼ cup of the milk and cream mixture, and whisk again.

Have a large bowl of iced water ready. Put the rest of the cream and milk mixture back on the burner and, when it is almost boiling, add the egg yolk mixture and whisk very quickly.

When you see the first bubbles appearing (if you have a thermometer this will be 185°F), take from the heat quickly and put the base of the pan into the ice water to cool it down as quickly as possible.

Before it is completely cold, blend with a hand blender until completely smooth, then put into the fridge until cold. Pass through a fine sieve and then into the siphon. Charge it, and then put the siphon into the fridge for 2 hours.

To serve, arrange some berries on each plate, then the ice cream and foam on top, and some tuile biscuits on the side, which you can use like spoons for the foam. Sprinkle the foam with superfine sugar and use a blowtorch to caramelize it quickly.

Sorbetto di menta, frutta della passione e schiuma di cocco

This is a quite soft jelly that we layer up with the sorbet and foam in a martini glass. Together the three flavors are unbelievable; very different, something you really have to taste for yourself – though some people, I know, don’t like the flavor of real coconut. I have had people tell me that it reminds them of soap or body lotion. I am so against the idea of soaps and shampoos and even household cleaners being made to smell of fruit – because it is so misleading, especially for kids. They think of apple as the aroma of a shampoo, instead of the real thing. I say only food should smell of food.

4 scoops of mint sorbet (to make your own, see page 560)

For the passion fruit jelly:

¼ cup water

⅔ cup superfine sugar

1 ¼ cups passion fruit juice

4g gelatin leaves, soaked in cold water and squeezed

For the coconut foam:

2 cups frozen coconut puree

6g gelatin leaves, soaked in cold water and squeezed

0.5-litre (2-cup)siphon, plus 1 charge

First make the jelly. To make the syrup, put the water in a pan with the sugar, bring to a boil, stirring to ensure all the sugar is dissolved, and then take off the heat and leave to cool. Mix the passion fruit juice and syrup together in a bowl. Warm 3 tablespoons of the mixture in a small pan. Remove from the heat, add the gelatin leaves and stir until dissolved. Add to the rest of the juice and syrup mixture, and stir well. Chill in the fridge for 2 hours until set.

To make the foam, warm 3 tablespoons of the coconut puree in a pan, then take off the heat, add the gelatin leaves and stir to dissolve. Add to the rest of the coconut puree. Put through a fine sieve.

Spoon the mixture into the siphon, charge it and put into the fridge for 2 hours.

Just before you want to use it, take the jelly from the fridge and break it up with a spoon.

To serve, put a scoop of sorbet into the bottom of a martini glass (or similar) and press down to make a neat layer. Add a spoonful of the broken-up jelly, then shake the siphon and squirt some coconut foam on top. Do this gently, to keep it from mixing with the jelly – the idea is to keep the three different-colored layers of sorbet, jelly and foam separate.

This is a very good, easy pastry that isn’t difficult to work with and won’t break if you roll it. We use it to line a nonstick tart pan and bake it “blind,” i.e., empty, so that it can cook a little and crisp up before you add a wet topping of fruit, frangipane, etc. We use ovenproof plastic wrap, filled with rice, dried peas or beans to weight it down, rather than baking paper, as it is tricky to keep this touching the pastry everywhere and keep it completely flat, whereas plastic wrap immediately sticks to it. Make sure you leave enough overlapping the edges to lift it out easily. Six minutes at 340°F is enough to start setting the pastry, then you can take out the plastic wrap and weights and return the tart case to the oven for about 15 minutes, until just golden, or whatever is required for your recipe. Make sure you preheat your oven for a good half hour before you start. It is easier to make double or even triple the quantity you need, as a larger volume will mix better, and you can freeze what you don’t use immediately.

Makes enough for two

11 -inch tarts or eight

4-inch tarts

1 cup butter

1 cup confectioner’s sugar

2 eggs

3 cups plus 2 tablespoons flour

With the paddle attachment on the mixer, blend the butter until soft. Add the sugar and continue to mix until the mixture turns pale. Add the eggs one by one, and when they are incorporated, add the flour. Continue to mix until all the flour is incorporated. Divide into 2 balls.

When the cherry season is over, you can make this with fresh red plums. You can also make one large 11-inch tart if you prefer.

Makes four 4-inch tarts

½ recipe quantity Sweet pastry

2 ½ cups fresh cherries (or plums), halved and pitted

about 2 tablespoons superfine sugar

For the frangipane:

7 tablespoons butter

½ cup superfine sugar

2 eggs

1 cup ground almonds (or hazelnuts)

3 ½ teaspoons flour

Roll out the pastry and use it to line four 4-inch nonstick tart tins. Then put the tins in the fridge for 2 hours to keep the pastry from shrinking in the oven.

Toward the end of that time, preheat the oven to 340°F. Line the chilled pastry cases with plastic wrap, fill with rice or dried peas or beans and bake blind for 4 minutes. Take out the weights, remove the plastic wrap, and put back into the oven for around 5 minutes (7 to 10 for a large tart), until baked but only very lightly colored (the base should feel firm when you touch it). Take out and turn the oven up to 180°C.

To make the frangipane, put the butter into a mixer with a paddle attachment and mix until soft. Add the sugar and continue mixing until the mixture turns pale. Add the eggs one by one until all are incorporated. Turn the speed to low and add the ground almonds and flour. Mix well, then turn the speed up to maximum for 1 to 2 minutes, no more, to incorporate some air, which will make the frangipane a little lighter and fluffier in texture (the mixture will turn paler and expand in volume a little).

Spread the frangipane over the tarts and arrange the cherries (or plums) cut side down over the top. Press the fruit down gently until it is completely embedded in the frangipane mixture.

Put back into the oven for about 12 minutes (15 to 20 for a larger one), during which time the frangipane will rise and turn golden. Halfway through the cooking time, sprinkle with the superfine sugar and return to the oven – some of the sugar will melt and caramelize, and give the tarts a rustic look.

Serve at room temperature.

Peaches and amaretti biscuits are a classic match that you will find in different variations all over Italy. The amaretto cream is really frangipane, with the addition of what, in the north of Italy, we talk about as bitter almonds (see page 576), but are actually bitter apricot kernels. They come not from the apricots we have in the fruit bowl but from immature fruit that looks very like almonds and are cultivated specifically for their kernels. You can buy them in specialty stores and health food shops.

Makes four 4-inch tarts

½ recipe quantity Sweet pastry (see page 536)

1 cup crushed amaretti cookies

10 small peaches

For the amaretto cream:

1 ¼ cups bitter apricot kernels

1 cup plus 2 tablespoons butter

1 ¾ cups superfine sugar

5 eggs

2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons flour, plus more for dusting

1 ½ cups ground almonds

Preheat the oven to 340°F

To make the amaretto cream, put the bitter apricot kernels into a food processor and grind to a powder. Put the butter in the bowl of an electric mixer with a paddle attachment and soften it. Add the sugar and mix for a minute or so until the mixture turns pale. Add the eggs one by one, mixing each one in well before adding the next. Switch off the machine and, with a spatula, scrape around the edges of the bowl until all the mixture is incorporated.

Mix together the flour, ground almonds and bitter apricot kernels, and stir into the butter mixture. Mix at a slow speed until everything is incorporated, then turn the speed up to maximum for 2 minutes to incorporate air. You will see that the mixture turns paler and expands in volume a little.

Roll out the pastry on a floured surface and use it to line four 4-inch nonstick tart tins, or one 11-inch one. Line the pastry shell with plastic wrap, weight with rice or dried peas or beans, and bake blind for 4 minutes. Take out the weights, remove the plastic wrap, and cook for 5 more minutes (7 to 10 minutes for a larger one), until lightly colored around the edges. Turn up the oven to 355°F.

Spoon the amaretto cream into the pastry cases in a layer about ¼ inch thick, smooth with a spatula and sprinkle the crushed amaretti cookies over the top. Halve the peaches and take out the pits. Arrange them alternately, one cut side up, then one cut side down, in a ring around each tart, and press down slightly into the cream.

Put into the oven and bake for about 12 minutes (or 15 to 20 for a larger one), until the amaretto cream is golden and has puffed up around the peaches.

Serve at room temperature.

This is a very thin and crispy tart, so thin we could almost call it pizza di mele – and have a bit of a game with words and serve it alongside the fruit lasagne (see page 521). It is the kind of French-influenced Milanese tart with a “wow factor” that we used to make at Olivo in the mornings, so it would look as though we had a pastry chef, when there were only three of us in the kitchen. You can make one big one or four individual ones. I find it is better to use a conventional oven rather than a convection oven, as you want the heat to be concentrated on the bottom of the pastry rather than circulating around it, so it crisps up quickly and uniformly. In summer, we also make this with halved cherries. Serve it with vanilla ice cream.

Makes four 4-inch tarts or one 11-inch tart

½ pound puff pastry

8 Granny Smith apples

about 2 tablespoons superfine sugar

For the pastry cream:

⅓ cup superfine sugar

½ cup cornstarch

yolks from 6 large eggs

13 ½ ounces milk

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon whipping cream

1 cinnamon stick

peel of 1 lemon (in a strip)

To serve:

Vanilla ice cream (optional, to make your own see page 561)

Preheat the oven to 355°F

To make the pastry cream, whisk the sugar, cornstarch and egg yolks together in a bowl until pale. Put the milk and cream in a pan with the cinnamon stick and lemon peel. Bring to a boil, then immediately take off the heat and leave to stand for 20 minutes for the flavors to infuse.

Slowly whisk the milk mixture into the sugar and egg mixture. Return to the heat, and when you see the first bubble, remove from the heat. Take out the cinnamon stick and lemon peel, and pass the mixture through a fine sieve.

Roll out the pastry into 4 circles of 4-inch diameter, or 1 of 11-inch diameter, and around ⅛ inch thick. Prick all over with a fork. Spread with pastry cream.

Halve the apples and remove their cores. Slice them about 1/16 inch thick (if the apples are just slightly thinner than the pastry, they should both cook properly in the same time). Arrange them in concentric circles, skin side up, embedding them well into the pastry cream – if they stick out they are likely to burn.

Put into the oven for about 20 to 30 minutes (another 5 minutes or so for a larger one), until the pastry is golden and crisp. Halfway through baking time, sprinkle with the superfine sugar, which will melt and caramelize a little to give the tarts a nice sheen – if the apples appear to be cooking too quickly, add a little extra sugar, as this will act as a barrier to the heat.

Serve at room temperature, with ice cream if you like.

Because the lemon and mascarpone mixture for this is quite liquid when it is first mixed, we completely cook the pastry case first, then turn the oven down, so that the topping can set without the pastry cooking further.

Serves 6–8

½ recipe quantity of Sweet pastry (see page 536)

2 egg yolks, beaten

confectioner’s sugar, to finish

For the filling:

1 ⅓ cups mascarpone cheese

¼ cup whipping cream

¼ cup milk

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon lemon juice

½ cup superfine sugar

½ cup egg yolks (from about 7 large eggs)

Preheat the oven to 340°F. Roll out the pastry and line an 11-inch nonstick tart tin with it. Line with ovenproof plastic wrap, fill with rice or dried peas or beans and bake blind for 4 minutes. Take out the weights, remove the plastic wrap and cook for around 10 to 12 minutes, until golden – the color you want it to be at the end.

Take out of the oven, brush the pastry all over with the beaten egg yolks and return to the oven for another 2 minutes. This forms a skin, so that even if there are tiny holes in the pastry, the topping won’t seep through and burn.

Turn the oven down to 230°F. The pastry is now cooked, so all you need to do is set the topping.

To make the topping, mix together the mascarpone, cream, milk, lemon juice and sugar in a bowl. Whisk the egg yolks separately, then add to the mascarpone mixture and incorporate quickly with a hand blender.

Spoon into the pastry and put into the oven for 20 to 25 minutes until the center is set but still the slightest bit wobbly. Leave to cool, during which time the topping will firm up.

To finish, dust the top with the confectioner’s sugar and caramelize it with a blowtorch. Serve at room temperature.

A true cheese is made with the milk of a cow, goat or sheep, but ricotta is made with the by-product of cheese making, whey. The story is that a long time ago, a shepherd left a pot on the fire with some whey in it after he had heated the milk to separate the curds from the whey to make a primitive cheese. When he returned, he found that the whey had been “recooked,” which is what ricotta means, and formed into lumps that tasted sweet.

These days ricotta is still made in a similar fashion, with the whey left over from making cheese such as provolone being reheated to a temperature of around 185°F. This causes the proteins to separate from the whey and rise to the surface in little lumps, which are skimmed off and left in rush baskets to drain. This is ricotta fresca (fresh ricotta), which is pure white, looks a little like cottage cheese, and is sold in tubs all over Italy but is traditional in southern cakes and desserts, such as Cannoli (see page 545) and the Easter tart, Pastiera Napoletana (see page 548) – where it takes the place of the mascarpone or cream of the north. Ricotta fresca is also fantastic in salads, or for mixing with herbs or spinach to fill ravioli.

Most of the ricotta we have in the north, where the production centers around Piemonte, is made with whey from cow’s milk and is very creamy, but it can also be made with the whey from sheep’s milk, which can have a much stronger flavor that isn’t really suitable for desserts, though it can also be quite mild (gentile). The most famous is ricotta romana, which traditionally comes only from the Agro Romano area of Lazio but has become a generic name for most ricotta – even cheese made with cow’s milk.

The curds can also be dry-salted and pressed, then matured in the curing room, so that the ricotta is semi-hard (ricotta salata) and can be grated over savory dishes such as the Sicilian maccheroni alla Norma, pasta with tomato, eggplant and basil. When it is aged more, it is called stagionata, and becomes more pungent and yellow in color, with a slightly piccante flavor. Dry-salted ricotta is also smoked (ricotta affumicata) by shutting it in a room where an aromatic fire is burning. In the north, beech wood is often used; in Abruzzo and Molise, where they make ricotta with the whey from pecorino production, they like juniper wood (ricotta al fumo di ginepro), and in Sardegna, herbs (ricotta mustia). I sometimes use smoked ricotta in a salad with baby onions in balsamic vinegar (see page 82). In Sicilia they do something different again, called ricotta infornata: sea salt is added to the whey, and when the cheese has chained, it is sprinkled with black pepper and baked in a stone oven for about half an hour.

Once when I was in Sicilia with the family, as if in a re-creation of the rustic origins of ricotta, we got talking to a shepherd, who made some ricotta from sheep’s milk for us for lunch over a fire in a field, using a wooden stirrer, and we ate it while it was still warm, or at least Plaxy and I did. As I say, sheep’s milk can be very strong. I thought it was quite incredible, I loved it, but the kids wouldn’t eat it, because they said it tasted too much of the animal. Jack still says it was the worst cheese he ever ate in his life.

I think this is the nicest of all the tarts and cakes we make in the restaurant. On the Amalfi coast in Campania (and also in Sicilia), they produce the cedro (citron), a bigger relative of the lemon that has a thick, nubby, aromatic zest, which is used to make candied peel. You can buy citron confit ready-made from Italian delicatessens – and sometimes, in season, the whole fruit, so you can make your own, as we do in the restaurant. The inspirational Patricia Michelson has them at her treasure trove of a shop and café, La Fromagerie in Marylebone (and High-bury) in London; or you could try Italian delis and also Jewish grocers and delis, as the particular variety of citron known as the etrog has a great significance in Jewish culture. Of course, you can make confit from normal lemons, but they won’t have quite such a distinctive flavor.

The way we do our confit is to make holes all over the skin of the cedri with a skewer, then put the whole fruits into a big pan with enough sugar syrup to cover. We then cook them very slowly over a gentle heat for about 4 hours (make the syrup using a ratio of 70 percent sugar to water, i.e., just under ¾ cup sugar for 1 cup of water). When the pan comes off the heat, we lay some parchment paper over the top of the cedri and place something heavy, such as another saucepan, on top to keep the fruit pressed down under the syrup. They stay like this for 5 to 6 hours, then we check that they are ready by taking one and cutting it in half. The flesh should be completely soft and the pith a uniform dark yellow. At this point, you can put the cedri into a sterilized jar (use disposable kitchen gloves to handle them, so you don’t transfer any bacteria into the jar) and cover with the syrup. That way they will keep for up to a year.

When you want to use the cedri, carefully cut off the peel (discarding the flesh) and cut it into strips. It will have a texture almost like marmalade, and the most fantastic rich flavor, which is beautiful with this ricotta tart.

When cherries are in season, we make this tart in the same way but substitute 1 ½ cups of fresh cherries, pitted and halved, for the citron – you don’t need any garnish.

Serves 6–8

½ recipe quantity Sweet pastry (see page 536)

1 ⅓ cups fresh ricotta cheese

2 eggs, plus 2 extra egg yolks

2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons honey

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

1 tablespoon plus 1 ¼ teaspoons Marsala

2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons caster sugar

1 cup citron or lemon confit (see above), plus more for garnish (optional)

For the meringue:

⅓ cup egg whites (from about 2 large eggs)

2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons caster sugar

Preheat the oven to 340°F.

Roll out the pastry and use it to line a 10-inch square tart tin. Line the pastry shell with ovenproof plastic wrap, fill with rice or dried peas or beans and bake blind for 5 minutes. Take out the weights, remove the plastic wrap and cook for 5 more minutes, until lightly colored around the edges. Turn down the oven to 300°F.

Put the ricotta, eggs and extra yolks, honey, cinnamon, Marsala and sugar into a bowl and whisk everything together, then chop the citron or lemon confit and mix that in.

Make the meringue by whisking the egg whites until you can make a trace with the whisk. Add the sugar very slowly until the mixture is firm and forming stiff peaks.

Take one-third of the meringue and fold it into the ricotta mixture, then fold in the rest very lightly.

Spread the mixture over the pastry base and cook for 15 to 20 minutes until golden. Allow to cool to room temperature to serve, and garnish with more thinly sliced citron or lemon confit if you like.

Traditionally, cannoli are made with strutto – snow-white pork fat that has a clean, quite neutral flavor – but you can use duck fat instead, or lard. You need a clean metal (¾ inch diameter) tube for this – it must be metal, as it has to go into hot oil. We serve this with Amaretto ice cream (see page 564) and Frangipane wafers twisted into corkscrew shapes (see page 575), and make a lighter lemon confit than in the previous recipe.

1 ⅓ cups plus 2 tablespoons flour

1 tablespoon plus 2 teaspoons sugar

2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons strutto, duck fat or lard

1 egg, plus a little more beaten egg for sealing the cannoli

3 tablespoons Muscat wine

vegetable oil, for deep-frying

For the lemon confit (optional):

1 lemon

1 ½ cups water

1 ¼ cups superfine sugar

For the vanilla syrup:

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon water

½ cup sugar

1 vanilla bean

For the filling:

1 cup ricotta cheese

4 ¼ tablespoons candied lemon peel, diced small

4 ¼ tablespoons candied orange peel, diced small

⅓ ounce dark chocolate (70 percent cocoa solids), cut in a similar size to the peel

5 roasted hazelnuts, cut in a similar size to the peel

¼ cup superfine sugar

¼ cup whipping cream

For the chocolate sauce (optional):

¼ cup water

2 heaping tablespoons sugar

2 tablespoons plus 1 teaspoon cocoa powder

⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon whipping cream

To serve:

confectiner’s sugar, for dusting

4 scoops of ice cream, preferably Amaretto

4 Frangipane wafers or cookies of your choice

Make the lemon confit a few horns ahead: peel the lemon (making sure not to include the bitter white pith) and cut the peel into julienne strips. Have ready a bowl of ice water. Bring a pan of water to a boil, then put in the strips of peel and blanch for 30 to 60 seconds. Lift out with a slotted spoon and plunge into the iced water. Discard the water in the pan, pour in some fresh boiling water and put in the peel to blanch again – just for 5 seconds this time, then lift out and put into the cold water again. This process will take out some of the bitterness.

Put 1 ½ cups water into a pan with 1 ¼ cups superfine sugar and heat. When the sugar is dissolved, add the blanched lemon and cook gently for 10 minutes until soft. Take off the heat and cool.

Make the cannoli a few hours ahead. To make the vanilla syrup, put ⅓ cup plus 1 tablespoon water in a pan with the sugar and vanilla bean, bring to a boil, stirring to dissolve the sugar, then take off the heat. Put the flour, sugar and fat into a mixer with a dough hook and mix for 2 minutes on medium until it resembles bread crumbs. Add the egg and mix some more, then add 2 ¼ teaspoons of vanilla syrup and the Muscat wine, and mix into a dough. Wrap in plastic and let rest for a few hours in the fridge.

When ready to use, roll out the dough as thin as possible and cut into 12 squares, about 2 ¾ x 2 ¾ inches. Wrap one square around the tube (see previous page) and seal with a little beaten egg.

Heat some vegetable oil in a deep-fat fryer or a large pan (no more than one-third full) and, with the help of a fish slice or skimmer, carefully lower the tube into the hot oil and fry until the cannolo turns golden brown. Lift out carefully with the fish slice or skimmer and drain on paper towels. When it has cooled just enough for you to touch it, slide the cannolo off the metal cylinder, and wrap the next square around it. Deep-fry as before. Repeat until all the cannoli are done.

Make the filling by mixing all the ingredients together.

To make the chocolate sauce, put the ¼ cup water and the sugar in a pan, bring to a boil, then add the cocoa powder. Bring back to a boil, add the cream, bring back to a boil again, then reduce the heat and cook slowly until the sauce is thick, dark and shiny. To test when it is ready, spoon a little onto a cold surface. It should keep its shape and set. Take the sauce off the heat and leave to cool – but don’t put it in the fridge, or it will lose its shine and become too hard.

Spoon the filling into a piping bag, and fill the cannoli. Dust with confectioner’s sugar. Arrange two small mounds of lemon confit on each plate (you could pack a small pastry cutter with the confit, to make a neat circle). Place a cannolo on one mound of confit, and a ball of ice cream on the other. Dot the chocolate sauce around. Top the ice cream with a Frangipane wafer or other cookie.

This is the traditional tart made in Napoli for the Easter festivities, and was originally made with grains of wheat, but is sometimes now made with pearl barley (soaked overnight and cooked according to instructions). The combination of ingredients may seem strange, but they are associated with ancient Roman celebrations of the rite of spring: flowers, eggs for new life, ricotta from the sheep, wheat and flour from the land – though the tart as we know it today is said to have been created, like so many of our sweet dishes, by a nun in a local convent. One of the many legends associated with the dish involves a mermaid called Partenope. One of the best stories is that she lived in the Gulf of Napoli, and to celebrate the arrival of spring each year she would come and sing to the inhabitants. One year, to say thank you for her songs, they offered her local gifts: ricotta, flour, eggs, wheat, perfumed orange flowers and spices. She was so delighted, she took them to her kingdom under the sea, where the gods mixed them together into a cake.

Serves 8–10

a little melted butter

1 pound (approximately ¾ recipe quantity) Sweet pastry (see page 536)

confectioner’s sugar to dust

For the filling:

¾ cup wheat grains (bulgur)

1 cup milk

pared peel from ½ lemon, left whole, the rest grated

2 pinches of ground cinnamon

½ cup superfine sugar

pinch of salt

1 cup fresh ricotta cheese

4 teaspoons orange flower water

⅓ cup candied citron (or lemon) peel and candied orange peel, chopped

3 eggs, separated