Rome & Lazio

Rome & Lazio Highlights

Rome

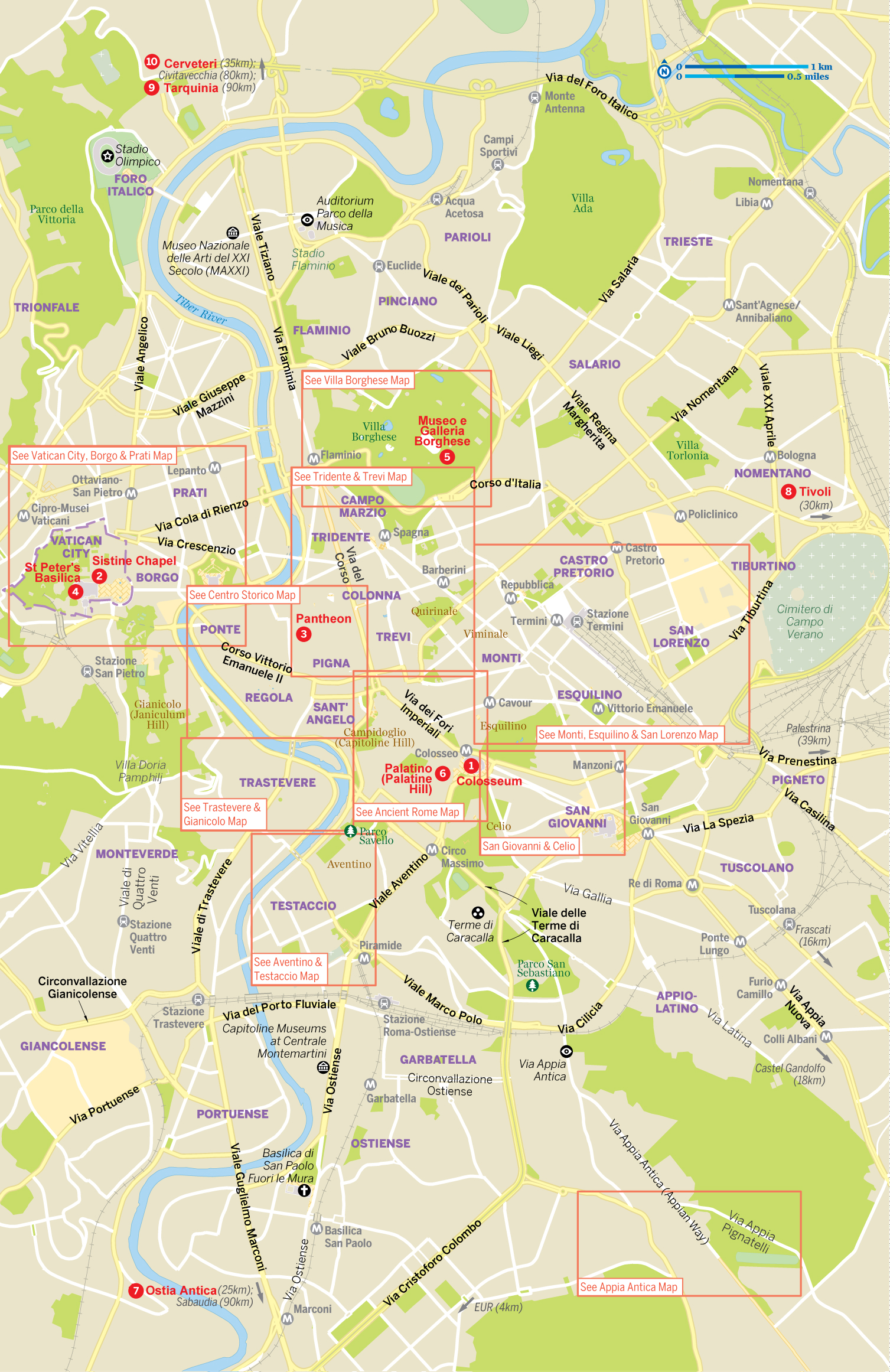

Neighbourhoods at a Glance

Colosseum

Palatino

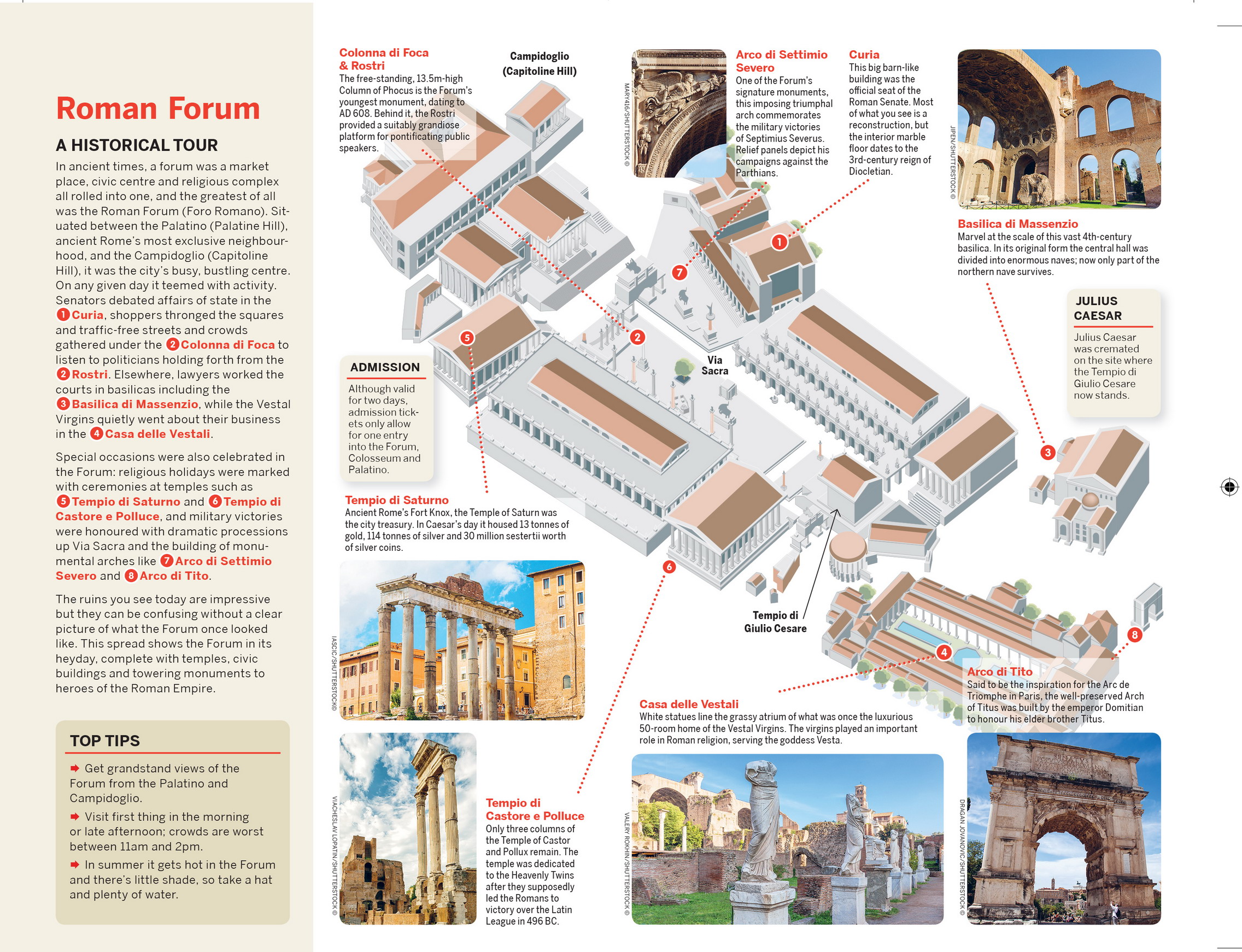

Roman Forum

Capitoline Museums

Pantheon

Piazza di Spagna & the Spanish Steps

Trevi Fountain

St Peter's Basilica

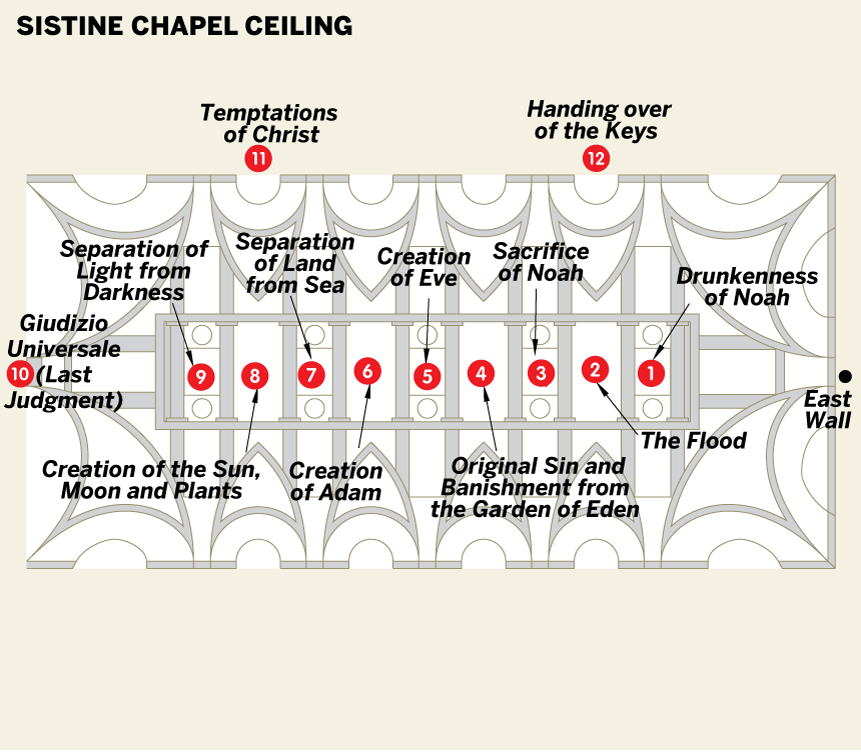

Vatican Museums

Lazio

Ostia Antica

Tivoli

Cerveteri

Tarquinia

Viterbo

Castelli Romani

Palestrina

South Coast

Isole Pontine

Rome & Lazio

Why Go?

From ancient treasures and artistic gems to remote hilltop monasteries, sandy beaches and volcanic lakes, Lazio is one of Italy’s great surprise packages. Its epic capital needs no introduction. Rome has been mesmerising travellers for millennia and still today it casts a powerful spell. Its romantic cityscape, piled high with martial ruins and iconic monuments, is achingly beautiful, and its museums and basilicas showcase some of the world’s most celebrated masterpieces.

But beyond the city, Lazio more than holds its own. Cerveteri and Tarquinia’s Etruscan tombs, Hadrian’s vast Tivoli estate, the remarkable ruins of Ostia Antica – these are sights to rival anything in the country.

Nature has contributed too, and the region boasts pockets of great natural beauty – lakes surrounded by lush green hills, wooded Apennine peaks and endless sandy beaches. Add fabulous food and wine and you have the perfect recipe for a trip to remember.

When to Go

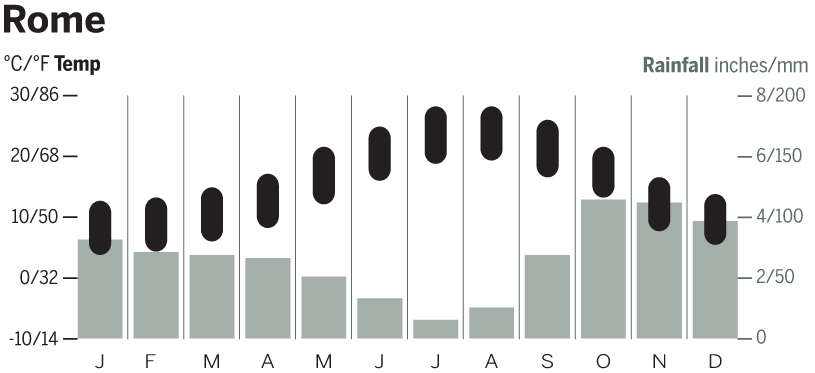

- Apr–Jun The best time for visiting Rome is spring. Easter is busy in Rome and peak rates apply.

- Jul–Aug Lazio's beaches and lakes get very busy in the peak summer months

- Sep–Oct Autumn is a good time for visiting regional sites. Festivals and outdoor events are on.

Best Places to Sleep

Rome & Lazio Highlights

1 Colosseum Getting your first spine-tingling glimpse of Rome's great gladiatorial arena.

2 Sistine Chapel Marvelling at Michelangelo's legendary frescoes in the heart of the Vatican Museums.

3 Pantheon Gazing heavenwards in this extraordinary Roman temple.

4 St Peter's Basilica Being blown away by the super-sized opulence of the Vatican's showpiece church.

5 Museo e Galleria Borghese Going face to face with sensational baroque sculpture.

6 Palatino Enjoying fabulous views from Rome's mythical birthplace.

7 Scavi Archeologici di Ostia Antica Strolling the fossilised streets of ancient Rome's main seaport.

8 Villa Adriana Poking around the monumental ruins of Hadrian's vast Tivoli estate.

9 Necropoli di Tarquinia Delving into frescoed Etruscan tombs in Tarquinia.

a Necropoli di Banditaccia Exploring rows of grass-capped tombs at Cerveteri's haunting city of the dead.

Rome

![]() %06 / Pop 2.86 million

%06 / Pop 2.86 million

History

Rome’s history spans three millennia, from the classical myths of vengeful gods to the follies of Roman emperors, from Renaissance excess and papal plotting to swaggering 20th-century fascism. Everywhere you go in this remarkable city, you’re surrounded by the past. Martial ruins, Renaissance palazzi (mansions) and flamboyant baroque basilicas all have tales to tell – of family feuding, historic upheavals, artistic rivalries, intrigues and dark passions.

Ancient Rome, the Myth

Rome’s original myth-makers were the first emperors. Eager to reinforce the city’s status as caput mundi (capital of the world), they turned to writers such as Virgil, Ovid and Livy to create an official Roman history. These authors, while adept at weaving epic narratives, were less interested in the rigours of historical research and frequently presented myth as reality. In the Aeneid, Virgil brazenly draws on Greek legends and stories to tell the tale of Aeneas, a Trojan prince who arrives in Italy and establishes Rome’s founding dynasty. Similarly, Livy, a writer celebrated for his monumental history of the Roman Republic, makes liberal use of mythology to fill the gaps in his historical narrative.

Ancient Rome’s rulers were sophisticated masters of spin and under their tutelage, art, architecture and elaborate public ceremony were employed to perpetuate the image of Rome as an invincible and divinely sanctioned power. Monuments such as the Ara Pacis, the Colonna di Traiano and the Arco di Costantino celebrated imperial glories, while gladiatorial games highlighted the Romans’ physical superiority. The Colosseum, the Roman Forum and the Pantheon were not only sophisticated feats of engineering, they were also impregnable symbols of Rome’s eternal might.

Legacy of an Empire

Rising out of the bloodstained remains of the Roman Republic, the Roman Empire was the Western world’s first great superpower. At its zenith under the emperor Trajan (r AD 98−117), it extended from Britannia in the north to North Africa in the south, from Hispania (Spain) in the west to Palestina (Palestine) and Syria in the east. Rome itself had more than 1.5 million inhabitants and the city sparkled with the trappings of imperial splendour: marble temples, public baths, theatres, circuses and libraries. Decline eventually set in during the 3rd century, and by the latter half of the 5th century, the city was in barbarian hands.

Emergence of Christianity

Christianity entered Rome's religious cocktail in the 1st century AD, sweeping in from Judaea, a Roman province in what is now Israel and the West Bank. Its early days were marred by persecution, most notably under Nero (r 54−68), but it slowly caught on, thanks to its popular message of heavenly reward and the evangelising efforts of Sts Peter and Paul. However, it was the conversion of the emperor Constantine (r 306−37) that really set Christianity on the path to European domination. In 313 Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, officially legalising Christianity, and later, in 378, Theodosius (r 379−95) made it Rome’s state religion. By this time, the Church had developed a sophisticated organisational structure based on five major sees: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem. At the outset, each bishopric carried equal weight, but in subsequent years Rome emerged as the senior party. The reasons for this were partly political – Rome was the wealthy capital of the Roman Empire – and partly religious – early Christian doctrine held that St Peter, founder of the Roman Church, had been sanctioned by Christ to lead the universal Church.

New Beginnings, Protest & Persecution

Bridging the gap between the Middle Ages and the modern era, the Renaissance (Rinascimento in Italian) was a far-reaching intellectual, artistic and cultural movement. It emerged in 14th-century Florence but quickly spread to Rome, where it gave rise to one of the greatest makeovers the city had ever seen. Not everyone was impressed though, and in the early 16th century the Protestant Reformation burst into life. This, in turn, provoked a furious response by the Catholic Church, the Counter-Reformation.

The Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation, the Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation, was marked by a second wave of artistic and architectural activity as the Church once again turned to bricks and mortar to restore its authority. But in contrast to the Renaissance, the Counter-Reformation was also a period of persecution and official intolerance. With the full blessing of Pope Paul III, Ignatius Loyola founded the Jesuits in 1540, and two years later the Holy Office was set up as the Church’s final appeals court for trials prosecuted by the Inquisition. In 1559 the Church published the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books) and began to persecute intellectuals and freethinkers. Galileo Galilei (1564−1642) was forced to renounce his assertion of the Copernican astronomical system, which held that the earth moved around the sun. He was summoned by the Inquisition to Rome in 1632 and exiled to Florence for the rest of his life. Giordano Bruno (1548−1600), a freethinking Dominican monk, fared worse. Arrested in Venice in 1592, he was burned at the stake eight years later in Campo de’ Fiori.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the Church’s policy of zero tolerance, the Counter-Reformation was largely successful in re-establishing papal prestige. And in this sense it can be seen as the natural finale to the Renaissance that Nicholas V had kicked off in 1450. From being a rural backwater with a population of around 20,000 in the mid-15th century, Rome had grown to become one of Europe’s great 17th-century cities.

Neighbourhoods at a Glance

1Ancient Rome

In a city of extraordinary beauty, Rome’s ancient heart stands out. It’s here you’ll find the great icons of the city’s past: the Colosseum; the Palatino; the forums; and the Campidoglio (Capitoline Hill), the historic home of the Capitoline Museums. Touristy by day, it’s quiet at night with few after-hours attractions.

2Centro Storico

A tightly packed tangle of animated piazzas, cobbled alleys, Renaissance palazzi and baroque churches, the historic centre is the Rome many come to find. Its romantic streets teem with boutiques, cafes, restaurants and stylish bars, while market traders and street artists work the crowds on the vibrant squares. The Pantheon and Piazza Navona are the star turns, but you’ll also find a whole host of monuments, museums and art-laden churches.

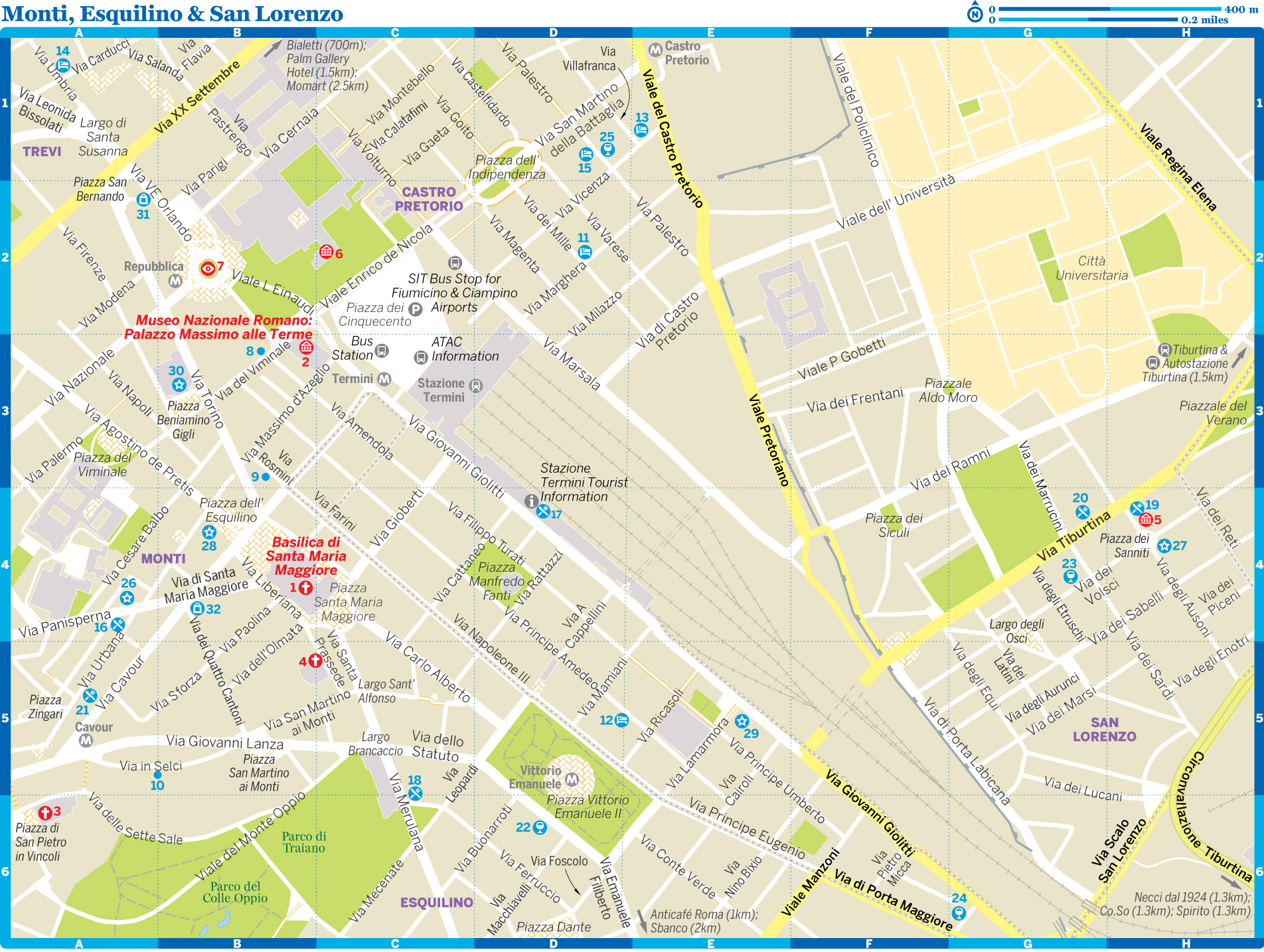

3Monti, Esquilino & San Lorenzo

Centred on transport hub Stazione Termini, this is a large and cosmopolitan area which, upon first glance, can seem busy and overwhelming. But hidden among its traffic-noisy streets are some beautiful churches, Rome’s best unsung art museum at Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, and any number of trendy bars and restaurants in the fashionable Monti, student-loved San Lorenzo and bohemian Pigneto districts.

4San Giovanni & Testaccio

Encompassing two of Rome's seven hills, this sweeping, multifaceted area offers everything from barnstorming basilicas and medieval churches to ancient ruins, colourful markets and popular clubs. Its best-known drawcards are the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano and Terme di Caracalla, but there are heavenly views to be had on the Aventino and Villa Celimontana is a lovely, tranquil park. Down by the river, Testaccio is a trendy district known for its nose-to-tail Roman cuisine and thumping nightlife.

5Southern Rome

Boasting a wealth of diversions, this huge area extends to Rome’s southern limits. Glorious ancient ruins lounge amid pea-green fields and towering umbrella pines along the cobbled Via Appia Antica, one of the world's oldest roads and pot-holed with subterranean catacombs. By contrast, post-industrial Ostiense blasts visitors straight back to the 21st century with its edgy street art, dining and nightlife. Then there's EUR, an Orwellian quarter of wide boulevards and linear buildings, which risks being the new fashionista hot spot with the arrival of Italian fashion house Fendi.

6Trastevere & Gianicolo

With its old-world cobbled lanes, ochre palazzi, ivy-clad facades and boho vibe, ever-trendy Trastevere is one of Rome’s most vivacious and Roman neighbourhoods – its very name, ‘across the Tiber’ (tras tevere), evokes both its geographical location and sense of difference. Outrageously photogenic and pleasurably car-free, its labyrinth of backstreet lanes heaves after dark as crowds swarm to its foodie and fashionable restaurants, cafes and bars. Rising up behind all this, Gianicolo Hill offers a breath of fresh air and a superb view of Rome laid out at your feet.

7Tridente, Trevi & the Quirinale

With the dazzling Trevi Fountain and Spanish Steps among its A-lister sights, this central part of Rome is glamorous, debonair and tourist-busy. Designer boutiques, fashionable bars, swish hotels and a handful of historic cafes and trattorias lace the compelling web of streets between Piazza di Spagna and Piazza del Popolo in Tridente, while the Trevi Fountain area south swarms with overpriced eateries and ticky-tacky shops. Lording over it all, the presidential Palazzo del Quirinale exudes sober authority – and wonderful views of the Rome skyline at sunset.

8Vatican City, Borgo & Prati

The Vatican, the world’s smallest sovereign state, sits over the river from the historic centre. Centred on the domed bulk of St Peter’s Basilica, it boasts some of Italy’s most revered artworks, many housed in the vast Vatican Museums (home of the Sistine Chapel), as well as batteries of overpriced restaurants and souvenir shops. Nearby, the landmark Castel Sant’Angelo looms over the Borgo district and upscale Prati offers excellent accommodation, eating and shopping.

9Villa Borghese & Northern Rome

This moneyed area encompasses Rome’s most famous park (Villa Borghese) and its most expensive residential district (Parioli). Concert-goers head to the Auditorium Parco della Musica, while art-lovers can choose between contemporary installations at MAXXI, Etruscan artefacts at the Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia or baroque treasures at the Museo e Galleria Borghese.

TOP SIGHT

Colosseum

An awesome, spine-tingling sight, the Colosseum is the most thrilling of Rome's ancient monuments. It was here that gladiators met in mortal combat and condemned prisoners fought off wild beasts in front of baying, bloodthirsty crowds. Two thousand years on and it's one of Italy's top tourist attractions, drawing more than six million visitors a year.

The Exterior

The outer walls have three levels of arches, framed by decorative columns topped by capitals of the Ionic (at the bottom), Doric and Corinthian (at the top) orders. They were originally covered in travertine and marble statues filled the niches on the 2nd and 3rd storeys. The upper level, punctuated with windows and slender Corinthian pilasters, had supports for 240 masts that held the awning over the arena, shielding the spectators from sun and rain. The 80 entrance arches, known as vomitoria, allowed the spectators to enter and be seated in a matter of minutes.

The Arena

The stadium originally had a wooden floor covered in sand – harena in Latin, hence the word ‘arena’ – to prevent combatants from slipping and to soak up spilt blood.

From the floor, trapdoors led down to the hypogeum, a subterranean complex of corridors, cages and lifts beneath the arena floor.

Hypogeum

The hypogeum served as the stadium’s backstage area. It was here that stage sets were prepared and combatants, both human and animal, would gather before showtime.

‘Gladiators entered the hypogeum through an underground corridor which led directly in from the nearby Ludus Magnus (gladiator school)’, explains the Colosseum’s Technical Director, Barbara Nazzaro.

A second gallery, the so-called Passaggio di Commodo (Passage of Commodus), was reserved for the emperor, allowing him to avoid the crowds as he entered the stadium.

To hoist people, animals and scenery up to the arena, the hypogeum had a sophisticated network of 80 winch-operated lifts, all controlled by a single pulley system.

The Seating

The cavea, or spectator seating, was divided into three tiers: magistrates and senior officials sat in the lowest tier, wealthy citizens in the middle and the plebs in the highest tier. Women (except for Vestal Virgins) were relegated to the cheapest sections at the top. And as in modern stadiums, tickets were numbered and spectators were assigned a precise seat in a specific sector – in 2015, restorers uncovered traces of red numerals on the arches, indicating how the sectors were numbered.

The podium, a broad terrace in front of the tiers of seats, was reserved for the emperor, senators and VIPs.

TOP SIGHT

Palatino

Sandwiched between the Roman Forum and the Circo Massimo, the Palatino (Palatine Hill) is an atmospheric area of towering pine trees, majestic ruins and memorable views. It was here that Romulus supposedly founded the city in 753 BC and Rome’s emperors lived in unabashed luxury.

Historical Development

Roman myth holds that Romulus founded Rome on the Palatino after he'd killed his twin Remus in a fit of anger. Archaeological evidence clearly can't prove this, but it has dated human habitation on the hill to the 8th century BC.

As the most central of Rome’s seven hills, and because it was close to the Roman Forum, the Palatino was ancient Rome’s most exclusive neighbourhood. The emperor Augustus lived here all his life and successive emperors built increasingly opulent palaces. But after Rome’s fall, it fell into disrepair and in the Middle Ages churches and castles were built over the ruins. Later, wealthy Renaissance families established gardens on the hill.

Most of the Palatino as it appears today is covered by the ruins of Emperor Domitian's vast complex, which served as the main imperial palace for 300 years. Divided into the Domus Flavia, Domus Augustana, and a stadio (stadium), it was built in the 1st century AD.

Stadio

On entering the Palatino from Via di San Gregorio, head uphill until you come to the first recognisable construction, the stadio. This sunken area, which was part of the main imperial palace, was used by the emperor for private games. A path to the side of the stadio leads to the towering remains of a complex built by Septimius Severus, comprising baths (Terme di Settimio Severo) and a palace (Domus Severiana) where, if they're open, you can visit the Arcate Severiane, a series of arches built to facilitate further development.

Casa di Livia & Casa di Augusto

Among the best-preserved buildings on the Palatino is the Casa di Livia, northwest of the Domus Flavia. Home to Augustus’ wife Livia, it was built around an atrium leading onto frescoed reception rooms. Nearby, the Casa di Augusto, Augustus’ private residence, features some superb frescoes in vivid reds, yellows and blues.

Domus Augustana & Domus Flavia

Next to the stadio are the ruins of the Domus Augustana, the emperor’s private quarters in the imperial palace. This was built on two levels, with rooms leading off a peristilio (peristyle or porticoed courtyard) on each floor. You can’t get down to the lower level, but from above you can see the basin of a big, square fountain and beyond it rooms that would originally have been paved in coloured marble.

North of the Museo Palatino is the Domus Flavia, the public part of the palace. This was centred on a grand columned peristyle – the grassy area with the base of an octagonal fountain – off which the main halls led: the emperor's audience chamber (aula Regia); a basilica where the emperor judged legal disputes; and a large banqueting hall, the triclinium.

Museo Palatino

The grey building next to the Domus houses the Museo Palatino, a small museum dedicated to the history of the area. Archaeological artefacts on show include a beautiful 1st-century bronze, the Erma di Canefora, and a celebrated 3rd-century graffito depicting a man with a donkey's head being crucified.

Orti Farnesiani

Covering the Domus Tiberiana (Tiberius’ palace) in the northwest corner of the Palatino, the Orti Farnesiani is one of Europe’s earliest botanical gardens. Named after Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, who had it laid out in the mid-16th century, it commands breathtaking views over the Roman Forum.

TOP SIGHT

Roman Forum

The Roman Forum was ancient Rome's showpiece centre, a grandiose district of temples, basilicas and vibrant public spaces. Nowadays, it's a collection of impressive, if sketchily labelled, ruins that can leave you drained and confused. But if you can get your imagination going, there’s something wonderfully compelling about walking in the footsteps of Julius Caesar and other legendary figures of Roman history.

Via Sacra Towards Campidoglio

Entering from Largo della Salara Vecchia – you can also enter from the Palatino or via an entrance near the Arco di Tito – you’ll see the Tempio di Antonino e Faustina ahead to your left. Erected in AD 141, this was transformed into a church in the 8th century, the Chiesa di San Lorenzo in Miranda. To your right, the 179 BC Basilica Fulvia Aemilia was a 100m-long public hall with a two-storey porticoed facade.

At the end of the path you'll come to Via Sacra, the Forum’s main thoroughfare, and the Tempio di Giulio Cesare (also known as the Tempio del Divo Giulio). Built by Augustus in 29 BC, this marks the spot where Julius Caesar was cremated.

Heading right up Via Sacra brings you to the Curia, the original seat of the Roman Senate. This barn-like construction was rebuilt on various occasions and what you see today is a 1937 reconstruction of how it looked in the reign of Diocletian (r 284–305).

In front of the Curia, and hidden by scaffolding, is the Lapis Niger, a large piece of black marble that's said to cover the tomb of Romulus.

At the end of Via Sacra, the 23m-high Arco di Settimio Severo is dedicated to the eponymous emperor and his sons, Caracalla and Geta. Close by are the remains of the Rostri, an elaborate podium where Shakespeare had Mark Antony make his famous 'Friends, Romans, countrymen…' speech. Facing this, the Colonna di Foca rises above what was once the Forum's main square, Piazza del Foro.

The eight granite columns that rise behind the Colonna are all that survive of the Tempio di Saturno, an important temple that doubled as the state treasury. Behind it are (from north to south): the ruins of the Tempio della Concordia, the Tempio di Vespasiano and the Portico degli Dei Consenti.

Via Sacra Towards Colosseum

Returning to Via Sacra you'll come to the Casa delle Vestali, home of the virgins who tended the flame in the adjoining Tempio di Vesta.

Further on, past the Tempio di Romolo, is the Basilica di Massenzio, the largest building on the Forum. Started by the Emperor Maxentius and finished by Constantine in 315, it originally measured approximately 100m by 65m.

Beyond the basilica, the Arco di Tito was built in AD 81 to celebrate Vespasian and Titus’ victories against rebels in Jerusalem.

Chiesa di Santa Maria Antiqua

The 6th-century Chiesa di Santa Maria Antiqua is the oldest Christian monument in the Forum. A treasure trove of early Christian art, it boasts exquisite 6th- to 9th-century frescoes and a hanging depiction of the Virgin Mary with child, one of the earliest icons in existence.

In front of the church is the Rampa imperiale (Imperial Ramp), a vast underground passageway that allowed the emperors to access the Forum from their Palatine palaces without being seen.

TOP SIGHT

Capitoline Museums

Housed in two stately palazzi on Piazza del Campidoglio, the Capitoline Museums are the world's oldest public museums. Their origins date to 1471, when Pope Sixtus IV donated a number of bronze statues to the city, forming the nucleus of what is now one of Italy's finest collections of classical sculpture. There's also a formidable picture gallery with works by many big-name Italian artists.

Entrance & Courtyard

The entrance to the museums is in Palazzo dei Conservatori, where you'll find the original core of the sculptural collection on the 1st floor, and the Pinacoteca (picture gallery) on the 2nd floor.

Before you head up to start on the sculpture collection proper, take a moment to admire the marble body parts littered around the ground-floor courtyard. The mammoth head, hand, and feet all belonged to a 12m-high statue of Constantine that once stood in the Basilica di Massenzio in the Roman Forum.

Palazzo dei Conservatori

Of the permanent sculpture collection on the 1st floor, the Etruscan Lupa Capitolina (Capitoline Wolf) is the most famous piece. Standing in the Sala della Lupa, this 5th-century-BC bronze wolf stands over her suckling wards, Romulus and Remus, who were added to the composition in 1471.

Other crowd-pleasers include the Spinario, a delicate 1st-century-BC bronze of a boy removing a thorn from his foot in the Sala dei Trionfi, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini's Medusa bust in the Sala delle Oche.

Also on this floor, in the modern wing known as the Esedra di Marco Aurelio, is an imposing bronze equestrian statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius – the original of the copy that stands in the piazza outside. Here you can also see the foundations of the Temple of Jupiter, one of the ancient city's most important temples that once stood on the Capitoline Hill.

Palazzo Nuovo

Palazzo Nuovo is crammed to its elegant 17th-century rafters with classical Roman sculpture.

From the lobby, where the curly-bearded Mars glares ferociously at everyone who passes by, stairs lead up to the main galleries where you'll find some real showstoppers. Chief among them is the Galata Morente (Dying Gaul) in the Sala del Gladiatore. One of the museum's greatest works, this sublime piece, actually a Roman copy of a 3rd-century-BC Greek original, movingly captures the quiet, resigned anguish of a dying Gaul warrior.

Next door, the Sala del Fauno takes its name from the red marble statue of a faun.

Another superb figurative piece is the sensual yet demure portrayal of the Venere Capitolina (Capitoline Venus) in the Gabinetto della Venere, off the main corridor.

Also worth a look are the busts of philosophers, poets and orators in the Sala dei Filosofi – look out for likenesses of Homer, Pythagoras, Socrates and Cicero.

Pinacoteca

The 2nd floor of Palazzo dei Conservatori is given over to the Pinacoteca, the museum's picture gallery. Dating to 1749, the collection is arranged chronologically with works from the Middle Ages through to the 18th century.

Each room harbours masterpieces but two stand out: the Sala Pietro da Cortona, which features Pietro da Cortona's famous depiction of the Ratto delle sabine (Rape of the Sabine Women; 1630), and the Sala di Santa Petronilla, named after Guercino's huge canvas Seppellimento di Santa Petronilla (The Burial of St Petronilla; 1621–23). This airy hall boasts a number of important canvases, including two by Caravaggio: La Buona Ventura (The Fortune Teller; 1595), which shows a gypsy pretending to read a young man's hand but actually stealing his ring, and San Giovanni Battista (John the Baptist; 1602), an unusual nude depiction of the youthful New Testament saint with a ram.

TOP SIGHT

Pantheon

A striking 2000-year-old temple, now a church, the Pantheon is Rome's best-preserved ancient monument and one of the most influential buildings in the Western world. Its greying, pockmarked exterior might look its age, but inside it's a different story, and it's a unique and exhilarating experience to pass through its vast bronze doors and gaze up at the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built.

History

In its current form the Pantheon dates to around AD 125. The original temple, built by Marcus Agrippa in 27 BC, burnt down in AD 80, and although it was rebuilt by Domitian, it was struck by lightning and destroyed for a second time in AD 110. The emperor Hadrian had it reconstructed between AD 118 and 125, and it's his version you see today.

Hadrian’s temple was dedicated to the classical gods – hence the name Pantheon, a derivation of the Greek words pan (all) and theos (god) – but in 608 it was consecrated as a Christian church after the Byzantine emperor Phocus donated it to Pope Boniface IV. It was dedicated to the Virgin Mary and all the martyrs and took on the name by which it is still officially known, the Basilica di Santa Maria ad Martyres.

Thanks to this consecration, it was spared the worst of the medieval plundering that reduced many of Rome’s ancient buildings to near dereliction. But it didn't escape entirely unscathed – its gilded-bronze roof tiles were removed and, in the 17th century, Pope Urban VIII had the portico’s bronze ceiling melted down to make 80 canons for Castel Sant’Angelo and to provide Bernini with bronze for the baldachin at St Peter's Basilica.

During the Renaissance, the building was much admired – Brunelleschi used it as inspiration for his cupola in Florence and Michelangelo studied it before designing the dome at St Peter's Basilica – and it became an important burial chamber. Today, you'll find the tomb of the artist Raphael here alongside those of kings Vittorio Emanuele II and Umberto I.

Exterior

Originally, the Pantheon was on a raised podium, its entrance facing onto a rectangular porticoed piazza. Nowadays, the dark-grey pitted exterior faces onto busy, cafe-lined Piazza della Rotonda. And while its facade is somewhat the worse for wear, it's still an imposing sight. The monumental entrance portico consists of 16 Corinthian columns, each 11.8m high and each made from a single block of Egyptian granite, supporting a triangular pediment. Behind the columns, two 20-tonne bronze doors – 16th-century restorations of the original portal – give onto the central rotunda.

Little remains of the ancient decor, although rivets and holes in the brickwork indicate where marble-veneer panels were once placed.

Interior

Although impressive from outside, it’s only when you get inside that you can really appreciate the Pantheon's full size. With light streaming in through the oculus (the 8.7m-diameter hole in the centre of the dome), the cylindrical marble-clad interior seems vast, an effect that was deliberately designed to cut worshippers down to size in the face of the gods.

Opposite the entrance is the church’s main altar, over which hangs a 7th-century icon of the Madonna col Bambino (Madonna and Child). To the left (as you look in from the entrance) is the tomb of Raphael, marked by Lorenzetto’s 1520 sculpture of the Madonna del Sasso (Madonna of the Rock). Neighbouring it are the tombs of King Umberto I and Margherita of Savoy. Over on the opposite side of the rotunda is the tomb of King Vittorio Emanuele II.

The Dome

The Pantheon’s dome, considered the Romans’ most important architectural achievement, was the largest dome in the world until the 15th century when Brunelleschi beat it with his Florentine cupola. Its harmonious appearance is due to a precisely calibrated symmetry – its diameter is exactly equal to the building’s interior height of 43.4m. At its centre, the oculus, which symbolically connected the temple with the gods, plays a vital structural role by absorbing and redistributing the dome's huge tensile forces.

Radiating out from the oculus are five rows of 28 coffers (indented panels). These were originally ornamented but more importantly served to reduce the cupola's immense weight.

TOP SIGHT

Piazza di Spagna & the Spanish Steps

A magnet for visitors since the 18th century, the Spanish Steps (Scalinata della Trinità dei Monti) rising up from Piazza di Spagna provide a perfect people-watching perch: think hot spot for selfies, newly-wed couples posing for romantic photos etc. In the late 1700s the area was much loved by English visitors on the Grand Tour and was known to locals as the ghetto de l’inglesi (the English ghetto).

Spanish Steps

Piazza di Spagna was named after the Spanish Embassy to the Holy See, but the staircase – 135 gleaming steps designed by the Italian Francesco de Sanctis and built in 1725 with a legacy from the French – leads up to the hilltop French Chiesa della Trinità dei Monti. The dazzling sweep of stairs reopened in September 2016 after a €1.5 million clean-up job funded by luxury Italian jewellery house Bulgari.

Chiesa della Trinità dei Monti

This landmark church (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 679 41 79; Piazza Trinità dei Monti 3;

%06 679 41 79; Piazza Trinità dei Monti 3; ![]() h7.30am-8pm Tue-Fri, 10am-5pm Sat & Sun;

h7.30am-8pm Tue-Fri, 10am-5pm Sat & Sun; ![]() mSpagna) was commissioned by King Louis XII of France and consecrated in 1585. Apart from the great city views from its front steps, it has some wonderful frescoes by Daniele da Volterra. His Deposizione (Deposition), in the second chapel on the left, is regarded as a masterpiece of mannerist painting.

mSpagna) was commissioned by King Louis XII of France and consecrated in 1585. Apart from the great city views from its front steps, it has some wonderful frescoes by Daniele da Volterra. His Deposizione (Deposition), in the second chapel on the left, is regarded as a masterpiece of mannerist painting.

Fontana della Barcaccia

At the foot of the steps, the fountain of a sinking boat, the Barcaccia (1627), is believed to be by Pietro Bernini, father of the more famous Gian Lorenzo. It’s fed from an aqueduct, the ancient Roman Acqua Vergine, as are the fountains in Piazza del Popolo and the Trevi Fountain. Here there's not much pressure, so it's sunken as a clever piece of engineering. Bees and suns decorate the structure, symbols of the commissioning Barberini family. It was damaged in 2015 by Dutch football fans, and the Dutch subsequently offered to repair the damage.

TOP SIGHT

Trevi Fountain

Rome's most famous fountain, the iconic Fontana di Trevi in Tridente, is a baroque extravaganza – a foaming white-marble and emerald-water masterpiece filling an entire piazza. The flamboyant baroque ensemble, 20m wide and 26m high, was designed by Nicola Salvi in 1732 and depicts sea-god Oceanus’ chariot being led by Tritons with seahorses – one wild, one docile – representing the moods of the sea.

Coin-tossing

The famous tradition (since the 1954 film Three Coins in the Fountain) is to toss a coin into the fountain, thus ensuring your return to Rome. Up to €3000 is thrown into the Trevi each day. This money is collected daily and goes to the Catholic charity Caritas, with its yield increasing significantly since the crackdown on people extracting the money for themselves.

Chiesa di Santissimi Vincenzo e Anastasio

After tossing your lucky coin into Trevi Fountain, nip into this 17th-century church (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; www.santivincenzoeanastasio.it; Vicolo dei Modelli 73; ![]() h9am-1pm & 4-8pm;

h9am-1pm & 4-8pm; ![]() mBarberini) overlooking Rome's most spectacular fountain. Originally known as the 'Papal church' due to its proximity to the papal residence on Quirinal Hill, the church safeguards the hearts and internal organs of dozens of popes – preserved in amphorae in a tiny gated chapel to the right of the apse. This practice began under Pope Sixtus V (1585–90) and continued until the 20th century when Pope Pius X (1903–14) decided it was not for him.

mBarberini) overlooking Rome's most spectacular fountain. Originally known as the 'Papal church' due to its proximity to the papal residence on Quirinal Hill, the church safeguards the hearts and internal organs of dozens of popes – preserved in amphorae in a tiny gated chapel to the right of the apse. This practice began under Pope Sixtus V (1585–90) and continued until the 20th century when Pope Pius X (1903–14) decided it was not for him.

TOP SIGHT

St Peter's Basilica

In a city of outstanding churches, none can hold a candle to St Peter’s, Italy’s largest, richest and most spectacular basilica. A monument to centuries of artistic genius, it boasts many spectacular works of art, including three of Italy's most celebrated masterpieces: Michelangelo’s Pietà, his soaring dome, and Bernini’s 29m-high baldachin over the papal altar.

Interior - The Nave

Dominating the centre of the basilica is Bernini’s 29m-high baldachin. Supported by four spiral columns and made with bronze taken from the Pantheon, it stands over the papal altar, also known as the Altar of the Confession. In front, Carlo Maderno's Confessione stands over the site where St Peter was originally buried.

Above the baldachin, Michelangelo’s dome soars to a height of 119m. Based on Brunelleschi's design for the Duomo in Florence, it's supported by four massive stone piers, each named after the saint whose statue adorns its Bernini-designed niche. The saints are all associated with the basilica's four major relics: the lance St Longinus used to pierce Christ's side; the cloth with which St Veronica wiped Jesus' face; a fragment of the Cross collected by St Helena; and the head of St Andrew.

At the base of the Pier of St Longinus is Arnolfo di Cambio's much-loved 13th-century bronze statue of St Peter, whose right foot has been worn down by centuries of caresses.

Behind the altar, the tribune is home to Bernini’s extraordinary Cattedra di San Pietro. A vast gilded bronze throne held aloft by four 5m-high saints, it's centred on a wooden seat that was once thought to have been St Peter’s but in fact dates to the 9th century. Above, light shines through a yellow window framed by a gilded mass of golden angels and adorned with a dove to represent the Holy Spirit.

To the right of the throne, Bernini’s monument to Urban VIII depicts the pope flanked by the figures of Charity and Justice.

Interior - Right Aisle

At the head of the right aisle is Michelangelo’s hauntingly beautiful Pietà. Sculpted when he was only 25 (in 1499), it’s the only work the artist ever signed – his signature is etched into the sash across the Madonna’s breast.

Nearby, a red floor disc marks the spot where Charlemagne and later Holy Roman emperors were crowned by the pope.

On a pillar just beyond the Pietà, Carlo Fontana’s gilt and bronze monument to Queen Christina of Sweden commemorates the far-from-holy Swedish monarch who converted to Catholicism in 1655.

Moving on, you'll come to the Cappella di San Sebastiano, home of Pope John Paul II's tomb, and the Cappella del Santissimo Sacramento, a sumptuously decorated baroque chapel with works by Borromini, Bernini and Pietro da Cortona.

Beyond the chapel, the grandiose monument to Gregory XIII sits near the roped-off Cappella Gregoriana, a chapel built by Gregory XIII from designs by Michelangelo.

Much of the right transept is closed off but you can still make out the monument to Clement XIII, one of Canova’s most famous works.

The Facade

Built between 1608 and 1612, Maderno’s immense facade is 48m high and 115m wide. Eight 27m-high columns support the upper attic on which 13 statues stand representing Christ the Redeemer, St John the Baptist and the 11 apostles. The central balcony is known as the Loggia della Benedizione, and it’s from here that the pope delivers his Urbi et Orbi blessing at Christmas and Easter.

Running across the entablature is an inscription, 'IN HONOREM PRINCIPIS APOST PAVLVS V BVRGHESIVS ROMANVS PONT MAX AN MDCXII PONT VII' which translates as 'In honour of the Prince of Apostles, Paul V Borghese, Roman, Pontiff, in the year 1612, the seventh of his pontificate'.

In the grand atrium, the Porta Santa (Holy Door) is opened only in Jubilee years.

TOP SIGHT

Vatican Museums

Visiting the Vatican Museums is a thrilling and unforgettable experience. With some 7km of exhibitions and more masterpieces than many small countries can call their own, this vast museum complex boasts one of the world’s greatest art collections. Highlights include a spectacular collection of classical statuary in the Museo Pio-Clementino, a suite of rooms frescoed by Raphael, and the Michelangelo-decorated Sistine Chapel.

Pinacoteca

Often overlooked by visitors, the papal picture gallery displays paintings dating from the 11th to 19th centuries, with works by Giotto, Fra' Angelico, Filippo Lippi, Perugino, Titian, Guido Reni, Guercino, Pietro da Cortona, Caravaggio and Leonardo da Vinci.

Look out for a trio of paintings by Raphael in Room VIII – the Madonna di Foligno (Madonna of Folignano), the Incoronazione della Vergine (Crowning of the Virgin), and La Trasfigurazione (Transfiguration), which was completed by his students after his death in 1520. Other highlights include Filippo Lippi's L'Incoronazione della Vergine con Angeli, Santo e donatore (Coronation of the Virgin with Angels, Saints, and donors); Leonardo da Vinci’s haunting and unfinished San Gerolamo (St Jerome); and Caravaggio’s Deposizione (Deposition from the Cross).

Museo Chiaramonti & Braccio Nuovo

This museum is effectively the long corridor that runs down the lower east side of the Palazzetto di Belvedere. Its walls are lined with thousands of statues and busts representing everything from immortal gods to playful cherubs and ugly Roman patricians.

Near the end of the hall, off to the right, is the Braccio Nuovo (New Wing), which contains a celebrated statue of the Nile as a reclining god covered by 16 babies.

Museo Pio-Clementino

This stunning museum contains some of the Vatican’s finest classical statuary, including the peerless Apollo Belvedere and the 1st-century BC Laocoön, both in the Cortile Ottagono (Octagonal Courtyard).

Before you go into the courtyard, take a moment to admire the 1st-century Apoxyomenos, one of the earliest known sculptures to depict a figure with a raised arm.

To the left as you enter the courtyard, the Apollo Belvedere is a 2nd-century Roman copy of a 4th-century-BC Greek bronze. A beautifully proportioned representation of the sun god Apollo, it’s considered one of the great masterpieces of classical sculpture. Nearby, the Laocoön depicts the mythical death of the Trojan priest who warned his fellow citizens not to take the wooden horse left by the Greeks.

Back inside, the Sala degli Animali is filled with sculpted creatures and some magnificent 4th-century mosaics. Continuing on, you come to the Sala delle Muse (Room of the Muses), centred on the Torso Belvedere, another of the museum’s must-sees. A fragment of a muscular 1st-century-BC Greek sculpture, this was found in Campo de’ Fiori and used by Michelangelo as a model for his ignudi (male nudes) in the Sistine Chapel.

The next room, the Sala Rotonda (Round Room), contains a number of colossal statues, including a gilded-bronze Ercole (Hercules) and an exquisite floor mosaic. The enormous basin in the centre of the room was found at Nero’s Domus Aurea and is made out of a single piece of red porphyry stone.

Museo Gregoriano Egizio

Founded by Pope Gregory XVI in 1839, this Egyptian museum displays pieces taken from Egypt in ancient Roman times. The collection is small but there are fascinating exhibits, including a fragmented statue of the pharaoh Ramses II on his throne, vividly painted sarcophagi dating from around 1000 BC, and a macabre mummy.

Museo Gregoriano Etrusco

At the top of the 18th-century Simonetti staircase, this fascinating museum contains artefacts unearthed in the Etruscan tombs of northern Lazio, as well as a superb collection of vases and Roman antiquities. Of particular interest is the Marte di Todi (Mars of Todi), a black bronze of a warrior dating to the late 5th century BC.

Stanze di Raffaello

These four frescoed chambers, currently undergoing partial restoration, were part of Pope Julius II’s private apartments. Raphael himself painted the Stanza della Segnatura (1508–11) and the Stanza d’Eliodoro (1512–14), while the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo (1514–17) and Sala di Costantino (1517–24) were decorated by students following his designs.

The first room you come to is the Sala di Costantino, originally a ceremonial reception room, which is dominated by the Battaglia di Costantino contro Maxentius (Battle of the Milvian Bridge) showing the victory of Constantine, Rome’s first Christian emperor, over his rival Maxentius.

Leading off the sala, but often closed to the public, the Cappella Niccolina, Pope Nicholas V's private chapel, boasts a superb cycle of frescoes by Fra' Angelico.

The Stanza d’Eliodoro, which was used for the pope's private audiences, takes its name from the Cacciata d’Eliodoro (Expulsion of Heliodorus from the Temple), reflecting Pope Julius II’s policy of forcing foreign powers off Church lands. To its right, the Messa di Bolsena (Mass of Bolsena) shows Julius paying homage to the relic of a 13th-century miracle at the lakeside town of Bolsena. Next is the Incontro di Leone Magno con Attila (Encounter of Leo the Great with Attila), and, on the fourth wall, the Liberazione di San Pietro (Liberation of St Peter), a brilliant work illustrating Raphael’s masterful ability to illustrate light.

The Stanza della Segnatura, Julius’ study and library, was the first room that Raphael painted, and it’s here that you’ll find his great masterpiece, La Scuola di Atene (The School of Athens), featuring philosophers and scholars gathered around Plato and Aristotle. The seated figure in front of the steps is believed to be Michelangelo, while the figure of Plato is said to be a portrait of Leonardo da Vinci, and Euclide (the bald man bending over) is Bramante. Raphael also included a self-portrait in the lower right corner – he’s the second figure from the right in the black hat. Opposite is La Disputa del Sacramento (Disputation on the Sacrament), also by Raphael.

The most famous work in the Stanza dell’Incendio di Borgo, the former seat of the Holy See's highest court and later a dining room, is the Incendio di Borgo (Fire in the Borgo). This depicts Leo IV extinguishing a fire by making the sign of the cross. The ceiling was painted by Raphael’s master, Perugino.

From the Raphael Rooms, stairs lead to the Appartamento Borgia and the Vatican’s collection of modern religious art.

Sistine Chapel

The jewel in the Vatican crown, the Cappella Sistina (Sistine Chapel) is home to two of the world’s most famous works of art – Michelangelo’s ceiling frescoes and his Giudizio Universale (Last Judgment).

Museum Tour: Sistine Chapel

Length: 30 minutes

On entering the chapel head over to the main entrance in the far (east) wall for the best views of the ceiling.

Michelangelo's design, which took him four years to complete, covers the entire 800-sq-metre surface. With painted architectural features and a colourful cast of biblical figures, it centres on nine panels depicting stories from the Book of Genesis.

As you look up from the east wall, the first panel is the 1Drunkenness of Noah, followed by 2The Flood, and the 3Sacrifice of Noah. Next, 4Original Sin and Banishment from the Garden of Eden famously depicts Adam and Eve being sent packing after accepting the forbidden fruit from Satan, represented by a snake with the body of a woman coiled around a tree. The 5Creation of Eve is then followed by the 6Creation of Adam. This, one of the most famous images in Western art, shows a bearded God pointing his finger at Adam, thus bringing him to life. Completing the sequence are the 7Separation of Land from Sea; the 8Creation of the Sun, Moon and Plants; and the 9Separation of Light from Darkness, featuring a fearsome God reaching out to touch the sun. Set around the central panels are 20 athletic male nudes, the so-called ignudi.

Straight ahead of you on the west wall is Michelangelo's mesmeric aGiudizio Universale (Last Judgment), showing Christ – in the centre near the top – passing sentence over the souls of the dead as they are torn from their graves to face him. The saved get to stay up in heaven (in the upper right) while the damned are sent down to face the demons in hell (in the bottom right).

The chapel's side walls also feature stunning Renaissance frescoes, representing the lives of Moses (to your left) and Christ (to the right). Look out for Botticelli's bTemptations of Christ and Perugino's great masterpiece, the cHanding over of the Keys.

Ancient Rome

1Top Sights

1Sights

6Drinking & Nightlife

7Shopping

1Sights

Ancient Rome

Arco di CostantinoMONUMENT

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via di San Gregorio; ![]() mColosseo)

mColosseo)

On the western side of the Colosseum, this monumental triple arch was built in AD 315 to celebrate the emperor Constantine's victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312). Rising to a height of 25m, it's the largest of Rome's surviving triumphal arches.

Carcere MamertinoHISTORIC SITE

(Carcer Tullianum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 6989 6375; www.operaromanapellegrinaggi.org; Clivo Argentario 1; adult/reduced €10/5;

%06 6989 6375; www.operaromanapellegrinaggi.org; Clivo Argentario 1; adult/reduced €10/5; ![]() h8.30am-4.30pm;

h8.30am-4.30pm; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali)

gVia dei Fori Imperiali)

Hidden beneath the 16th-century Chiesa di San Giuseppe dei Falegnami, the Mamertine Prison was ancient Rome's maximum-security jail. St Peter did time here and while imprisoned, supposedly created a miraculous stream of water to baptise his jailers.

On its bare stone walls, you can make out traces of medieval frescoes depicting Jesus, the Virgin Mary and Sts Peter and Paul.

Imperial ForumsARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE

(Fori Imperiali;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali)

gVia dei Fori Imperiali)

Visible from Via dei Fori Imperiali and, when it's open, Via Alessandrina, the forums of Trajan, Augustus, Nerva and Caesar are known collectively as the Imperial Forums. These were largely buried when Mussolini bulldozed Via dei Fori Imperiali through the area in 1933, but excavations have since unearthed much of them. The standout sights are the Mercati di Traiano (Trajan's Markets), accessible through the Museo dei Fori Imperiali, and the landmark Colonna Traiana (Trajan’s Column;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali).

gVia dei Fori Imperiali).

Little recognisable remains of the Foro di Traiano (Trajan’s Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali), except for some pillars from the Basilica Ulpia (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums;

gVia dei Fori Imperiali), except for some pillars from the Basilica Ulpia (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali) and the Colonna Traiana, whose minutely detailed reliefs celebrate Trajan's military victories over the Dacians (from modern-day Romania).

gVia dei Fori Imperiali) and the Colonna Traiana, whose minutely detailed reliefs celebrate Trajan's military victories over the Dacians (from modern-day Romania).

To the southeast, three temple columns arise from the ruins of the Foro di Augusto (Augustus’ Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali), now mostly under Via dei Fori Imperiali. The 30m-high wall behind the forum was built to protect it from the fires that frequently swept down from the nearby Suburra slums.

gVia dei Fori Imperiali), now mostly under Via dei Fori Imperiali. The 30m-high wall behind the forum was built to protect it from the fires that frequently swept down from the nearby Suburra slums.

The Foro di Nerva (Nerva’s Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali) was also buried by Mussolini's road-building, although part of a temple dedicated to Minerva still stands. Originally, it would have connected the Foro di Augusto to the 1st-century Foro di Vespasiano (Vespasian’s Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums;

gVia dei Fori Imperiali) was also buried by Mussolini's road-building, although part of a temple dedicated to Minerva still stands. Originally, it would have connected the Foro di Augusto to the 1st-century Foro di Vespasiano (Vespasian’s Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali), also known as the Foro della Pace (Forum of Peace). On the other side of the road, three columns on a raised platform are the most visible remains of the Foro di Cesare (Caesar’s Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums;

gVia dei Fori Imperiali), also known as the Foro della Pace (Forum of Peace). On the other side of the road, three columns on a raised platform are the most visible remains of the Foro di Cesare (Caesar’s Forum;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Via dei Fori Imperiali, Imperial Forums; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali).

gVia dei Fori Imperiali).

![]() oMercati di Traiano Museo dei Fori ImperialiMUSEUM

oMercati di Traiano Museo dei Fori ImperialiMUSEUM

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 06 08; www.mercatiditraiano.it; Via IV Novembre 94; adult/reduced €11.50/9.50;

%06 06 08; www.mercatiditraiano.it; Via IV Novembre 94; adult/reduced €11.50/9.50; ![]() h9.30am-7.30pm, last admission 6.30pm;

h9.30am-7.30pm, last admission 6.30pm; ![]() gVia IV Novembre)

gVia IV Novembre)

This striking museum brings to life the Mercati di Traiano, Emperor Trajan's great 2nd-century complex, while also providing a fascinating introduction to the Imperial Forums with multimedia displays, explanatory panels and a smattering of archaeological artefacts.

Sculptures, friezes and the occasional bust are set out in rooms opening onto what was once the Great Hall. But more than the exhibits, the real highlight here is the chance to explore the echoing ruins of the vast complex. The three-storey hemicycle was originally thought to have housed markets and shops – hence its name – but historians now believe it was largely used to house the forum's administrative offices.

Rising above the markets is the Torre delle Milizie (Militia Tower;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() gVia IV Novembre), a 13th-century red-brick tower.

gVia IV Novembre), a 13th-century red-brick tower.

Piazza del CampidoglioPIAZZA

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() gPiazza Venezia)

gPiazza Venezia)

This hilltop piazza, designed by Michelangelo in 1538, is one of Rome's most beautiful squares. There are several approaches but the most dramatic is via the graceful Cordonata ( MAP GOOGLE MAP ; Piazza d'Aracoeli) staircase up from Piazza d'Aracoeli.

The piazza is flanked by Palazzo Nuovo and Palazzo dei Conservatori, together home to the Capitoline Museums, and Palazzo Senatorio, the seat of Rome city council. In the centre is a copy of an equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius.

The original, which dates to the 2nd century AD, is in the Capitoline Museums.

Chiesa di Santa Maria in AracoeliCHURCH

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Scala dell'Arce Capitolina; ![]() h9am-6.30pm summer, to 5.30pm winter;

h9am-6.30pm summer, to 5.30pm winter; ![]() gPiazza Venezia)

gPiazza Venezia)

Atop the steep 14th-century Aracoeli staircase, this 6th-century Romanesque church marks the highest point of the Campidoglio. Its rich interior boasts several treasures including a wooden gilt ceiling, an impressive Cosmatesque floor and a series of 15th-century Pinturicchio frescoes illustrating the life of St Bernardine of Siena. Its main claim to fame, though, is a wooden baby Jesus that's thought to have healing powers.

VittorianoMONUMENT

(Victor Emanuel Monument;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Venezia; ![]() h9.30am-5.30pm summer, to 4.30pm winter;

h9.30am-5.30pm summer, to 4.30pm winter; ![]() gPiazza Venezia)

gPiazza Venezia)![]() F

F

Love it or loathe it (as many Romans do), you can't ignore the Vittoriano (aka the Altare della Patria, Altar of the Fatherland), the massive mountain of white marble that towers over Piazza Venezia. Begun in 1885 to honour Italy's first king, Vittorio Emanuele II – who's immortalised in its vast equestrian statue – it incorporates the Museo Centrale del Risorgimento (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 679 35 98; www.risorgimento.it; Vittoriano, Piazza Venezia; adult/reduced €5/2.50;

%06 679 35 98; www.risorgimento.it; Vittoriano, Piazza Venezia; adult/reduced €5/2.50; ![]() h9.30am-6.30pm;

h9.30am-6.30pm; ![]() gPiazza Venezia), a small museum documenting Italian unification, and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

gPiazza Venezia), a small museum documenting Italian unification, and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

For Rome's best 360-degree views, take the Roma dal Cielo (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Vittoriano, Piazza Venezia; adult/reduced €7/3.50; ![]() h9.30am-7.30pm, last admission 7pm;

h9.30am-7.30pm, last admission 7pm; ![]() gPiazza Venezia) lift to the top.

gPiazza Venezia) lift to the top.

Housed in the monument's eastern wing is the Complesso del Vittoriano (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 871 51 11; www.ilvittoriano.com; Via di San Pietro in Carcere; admission variable;

%06 871 51 11; www.ilvittoriano.com; Via di San Pietro in Carcere; admission variable; ![]() h9.30am-7.30pm Mon-Thu, to 10pm Fri & Sat, to 8.30pm Sun;

h9.30am-7.30pm Mon-Thu, to 10pm Fri & Sat, to 8.30pm Sun; ![]() gVia dei Fori Imperiali), a gallery space that regularly hosts major art exhibitions.

gVia dei Fori Imperiali), a gallery space that regularly hosts major art exhibitions.

Palazzo VeneziaHISTORIC BUILDING

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Venezia; ![]() gPiazza Venezia)

gPiazza Venezia)

Built between 1455 and 1464, this was the first of Rome's great Renaissance palaces. For centuries it served as the embassy of the Venetian Republic – hence its name – but it's most readily associated with Mussolini, who installed his office here in 1929, and famously made speeches from the balcony. Nowadays, it's home to the tranquil Museo Nazionale del Palazzo Venezia (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 6999 4283; www.museopalazzovenezia.beniculturali.it; Via del Plebiscito 118; adult/reduced €5/2.50;

%06 6999 4283; www.museopalazzovenezia.beniculturali.it; Via del Plebiscito 118; adult/reduced €5/2.50; ![]() h8.30am-7.30pm Tue-Sun;

h8.30am-7.30pm Tue-Sun; ![]() gPiazza Venezia) and its eclectic collection of Byzantine and early Renaissance paintings, ceramics, bronze figures, weaponry and armour.

gPiazza Venezia) and its eclectic collection of Byzantine and early Renaissance paintings, ceramics, bronze figures, weaponry and armour.

Basilica di San MarcoBASILICA

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza di San Marco 48; ![]() h10am-1pm Tue-Sun & 4-6pm Tue-Fri, 4-8pm Sat & Sun;

h10am-1pm Tue-Sun & 4-6pm Tue-Fri, 4-8pm Sat & Sun; ![]() gPiazza Venezia)

gPiazza Venezia)

The early-4th-century Basilica di San Marco stands over the house where St Mark the Evangelist is said to have stayed while in Rome. Its main attraction is the golden 9th-century apse mosaic showing Christ flanked by several saints and Pope Gregory IV.

Bocca della VeritàMONUMENT

(Mouth of Truth;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Bocca della Verità 18; ![]() h9.30am-5.50pm;

h9.30am-5.50pm; ![]() gPiazza Bocca della Verità)

gPiazza Bocca della Verità)

A bearded face carved into a giant marble disc, the Bocca della Verità is one of Rome's most popular curiosities. Legend has it that if you put your hand in the mouth and tell a lie, the Bocca will slam shut and bite your hand off.

The mouth, which was originally part of a fountain, or possibly an ancient manhole cover, now lives in the portico of the Chiesa di Santa Maria in Cosmedin, a handsome medieval church.

Centro Storico

1Top Sights

1Sights

4Sleeping

5Eating

6Drinking & Nightlife

3Entertainment

7Shopping

Centro Storico

Basilica di Santa Maria Sopra MinervaBASILICA

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; www.santamariasopraminerva.it; Piazza della Minerva 42; ![]() h6.40am-7pm Mon-Fri, 6.40am-12.30pm & 3.30-7pm Sat, 8am-12.30pm & 3.30-7pm Sun;

h6.40am-7pm Mon-Fri, 6.40am-12.30pm & 3.30-7pm Sat, 8am-12.30pm & 3.30-7pm Sun; ![]() gLargo di Torre Argentina)

gLargo di Torre Argentina)

Built on the site of three pagan temples, including one dedicated to the goddess Minerva, the Dominican Basilica di Santa Maria Sopra Minerva is Rome’s only Gothic church. However, little remains of the original 13th-century structure and these days the main drawcard is a minor Michelangelo sculpture and the magisterial, art-rich interior.

Inside, to the right of the altar in the Cappella Carafa (also called the Cappella della Annunciazione), you’ll find some superb 15th-century frescoes by Filipino Lippi and the majestic tomb of Pope Paul IV.

Left of the high altar is one of Michelangelo’s lesser-known sculptures, Cristo Risorto (Christ Bearing the Cross; 1520), depicting Jesus carrying a cross while wearing some jarring bronze drapery. This wasn't part of the original composition and was added after the Council of Trent (1545–63) to preserve Christ's modesty.

An altarpiece of the Madonna and Child in the second chapel in the northern transept is attributed to Fra' Angelico, the Dominican friar and painter, who is also buried in the church.

The body of St Catherine of Siena, minus her head (which is in Siena), lies under the high altar, and the tombs of two Medici popes, Leo X and Clement VII, are in the apse.

![]() oGalleria Doria PamphiljGALLERY

oGalleria Doria PamphiljGALLERY

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 679 73 23; www.doriapamphilj.it; Via del Corso 305; adult/reduced €12/8;

%06 679 73 23; www.doriapamphilj.it; Via del Corso 305; adult/reduced €12/8; ![]() h9am-7pm, last entry 6pm;

h9am-7pm, last entry 6pm; ![]() gVia del Corso)

gVia del Corso)

Hidden behind the grimy grey exterior of Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, this wonderful gallery boasts one of Rome’s richest private art collections, with works by Raphael, Tintoretto, Titian, Caravaggio, Bernini and Velázquez, as well as several Flemish masters. Masterpieces abound, but the undisputed star is Velázquez' portrait of an implacable Pope Innocent X, who grumbled that the depiction was 'too real'. For a comparison, check out Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s sculptural interpretation of the same subject.

Chiesa di Sant’Ignazio di LoyolaCHURCH

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; www.santignazio.gesuiti.it; Piazza di Sant’Ignazio; ![]() h7.30am-7pm Mon-Sat, 9am-7pm Sun;

h7.30am-7pm Mon-Sat, 9am-7pm Sun; ![]() gVia del Corso)

gVia del Corso)

Flanking a delightful rococo piazza, this important Jesuit church boasts a Carlo Maderno facade and two celebrated trompe l'oeil frescoes by Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709). One cleverly depicts a fake dome, while the other, on the nave ceiling, shows St Ignatius Loyola being welcomed into paradise by Christ and the Madonna.

![]() oChiesa di San Luigi dei FrancesiCHURCH

oChiesa di San Luigi dei FrancesiCHURCH

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza di San Luigi dei Francesi 5; ![]() h9.30am-12.45pm & 2.30-6.30pm Mon-Fri, 9.30am-12.15pm & 2.30-6.45pm Sat, 11.30am-12.45pm & 2.30-6.45pm Sun;

h9.30am-12.45pm & 2.30-6.30pm Mon-Fri, 9.30am-12.15pm & 2.30-6.45pm Sat, 11.30am-12.45pm & 2.30-6.45pm Sun; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento)

gCorso del Rinascimento)

Church to Rome’s French community since 1589, this opulent baroque chiesa is home to a celebrated trio of Caravaggio paintings: the Vocazione di San Matteo (The Calling of Saint Matthew), the Martirio di San Matteo (The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew) and San Matteo e l’angelo (Saint Matthew and the Angel), known collectively as the St Matthew cycle.

These three canvases, housed in the Cappella Contarelli to the left of the main altar, are among the earliest of Caravaggio's religious works, painted between 1600 and 1602, but they are inescapably his, featuring a down-to-earth realism and the stunning use of chiaroscuro (the bold contrast of light and dark).

Before you leave the church, take a moment to enjoy Domenichino’s faded 17th-century frescoes of St Cecilia in the second chapel on the right. St Cecilia is also depicted in the altarpiece by Guido Reni, which is a copy of a work by Raphael.

![]() oMuseo Nazionale Romano: Palazzo AltempsMUSEUM

oMuseo Nazionale Romano: Palazzo AltempsMUSEUM

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 3996 7700; www.coopculture.it; Piazza Sant'Apollinare 44; adult/reduced €7/3.50;

%06 3996 7700; www.coopculture.it; Piazza Sant'Apollinare 44; adult/reduced €7/3.50; ![]() h9am-7.45pm Tue-Sun;

h9am-7.45pm Tue-Sun; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento)

gCorso del Rinascimento)

Just north of Piazza Navona, Palazzo Altemps is a beautiful late-15th-century palazzo, housing the best of the Museo Nazionale Romano’s formidable collection of classical sculpture. Many pieces come from the celebrated Ludovisi collection, amassed by Cardinal Ludovico Ludovisi in the 17th century.

Prize exhibits include the beautiful 5th-century Trono Ludovisi (Ludovisi Throne), a carved marble block whose central relief depicts a naked Venus (Aphrodite) being modestly plucked from the sea. In the neighbouring room, the Ares Ludovisi, a 2nd-century-BC representation of a young, clean-shaven Mars, owes its right foot to a Gian Lorenzo Bernini restoration in 1622.

Another affecting work is the sculptural group Galata Suicida (Gaul’s Suicide), a melodramatic depiction of a Gaul knifing himself to death over a dead woman.

The building itself provides an elegant backdrop with a grand central courtyard and frescoed rooms. These include the Sala delle Prospettive Dipinte, which was painted with landscapes and hunting scenes for Cardinal Altemps, the rich nephew of Pope Pius IV (r 1560–65) who bought the palazzo in the late 16th century.

The museum also houses the Museo Nazional Romano’s Egyptian collection.

![]() oPiazza NavonaPIAZZA

oPiazza NavonaPIAZZA

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento)

gCorso del Rinascimento)

With its showy fountains, baroque palazzi and colourful cast of street artists, hawkers and tourists, Piazza Navona is central Rome’s elegant showcase square. Built over the 1st-century Stadio di Domiziano (Domitian’s Stadium;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 4568 6100; www.stadiodomiziano.com; Via di Tor Sanguigna 3; adult/reduced €8/6;

%06 4568 6100; www.stadiodomiziano.com; Via di Tor Sanguigna 3; adult/reduced €8/6; ![]() h10am-7pm Sun-Fri, to 8pm Sat;

h10am-7pm Sun-Fri, to 8pm Sat; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento), it was paved over in the 15th century and for almost 300 years hosted the city's main market. Its grand centrepiece is Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of the Four Rivers;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Navona;

gCorso del Rinascimento), it was paved over in the 15th century and for almost 300 years hosted the city's main market. Its grand centrepiece is Bernini’s Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of the Four Rivers;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Navona; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento), a flamboyant fountain featuring an Egyptian obelisk and muscular personifications of the rivers Nile, Ganges, Danube and Plate.

gCorso del Rinascimento), a flamboyant fountain featuring an Egyptian obelisk and muscular personifications of the rivers Nile, Ganges, Danube and Plate.

Legend has it that the Nile figure is shielding his eyes from the nearby Chiesa di Sant’Agnese in Agone (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 6819 2134; www.santagneseinagone.org; Piazza Navona; concerts €13;

%06 6819 2134; www.santagneseinagone.org; Piazza Navona; concerts €13; ![]() h9.30am-12.30pm & 3.30-7pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm & 4-8pm Sun;

h9.30am-12.30pm & 3.30-7pm Tue-Sat, 9am-1pm & 4-8pm Sun; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento) designed by Bernini’s hated rival, Francesco Borromini. In truth, Bernini completed his fountain two years before his contemporary started work on the church's facade and the gesture simply indicated that the source of the Nile was unknown at the time.

gCorso del Rinascimento) designed by Bernini’s hated rival, Francesco Borromini. In truth, Bernini completed his fountain two years before his contemporary started work on the church's facade and the gesture simply indicated that the source of the Nile was unknown at the time.

The Fontana del Moro (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Navona; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento) at the southern end of the square was designed by Giacomo della Porta in 1576. Bernini added the Moor holding a dolphin in the mid-17th century, but the surrounding Tritons are 19th-century copies. At the northern end of the piazza, the 19th-century Fontana del Nettuno (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Navona;

gCorso del Rinascimento) at the southern end of the square was designed by Giacomo della Porta in 1576. Bernini added the Moor holding a dolphin in the mid-17th century, but the surrounding Tritons are 19th-century copies. At the northern end of the piazza, the 19th-century Fontana del Nettuno (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; Piazza Navona; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento) depicts Neptune fighting with a sea monster, surrounded by sea nymphs.

gCorso del Rinascimento) depicts Neptune fighting with a sea monster, surrounded by sea nymphs.

The piazza's largest building is Palazzo Pamphilj (

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; http://roma.itamaraty.gov.br/it; Piazza Navona; ![]() hby reservation only;

hby reservation only; ![]() gCorso del Rinascimento), built for Pope Innocent X between 1644 and 1650, and now home to the Brazilian embassy.

gCorso del Rinascimento), built for Pope Innocent X between 1644 and 1650, and now home to the Brazilian embassy.

Palazzo FarneseHISTORIC BUILDING

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; www.inventerrome.com; Piazza Farnese; €9; ![]() hguided tours 3pm, 4pm & 5pm Mon, Wed & Fri;

hguided tours 3pm, 4pm & 5pm Mon, Wed & Fri; ![]() gCorso Vittorio Emanuele II)

gCorso Vittorio Emanuele II)

Home of the French embassy, this formidable Renaissance palazzo, one of Rome's finest, was started in 1514 by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, continued by Michelangelo and finished by Giacomo della Porta. Inside, it boasts a series of frescoes by Annibale and Agostino Carracci that are said by some to rival Michelangelo's in the Sistine Chapel. The highlight, painted between 1597 and 1608, is the monumental ceiling fresco Amori degli Dei (The Loves of the Gods) in the Galleria dei Carracci.

Palazzo SpadaHISTORIC BUILDING

(Palazzo Capodiferro;

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 683 2409; http://galleriaspada.beniculturali.it; Piazza Capo di Ferro 13; adult/reduced €5/2.50;

%06 683 2409; http://galleriaspada.beniculturali.it; Piazza Capo di Ferro 13; adult/reduced €5/2.50; ![]() h8.30am-7.30pm Wed-Mon;

h8.30am-7.30pm Wed-Mon; ![]() gCorso Vittorio Emanuele II)

gCorso Vittorio Emanuele II)

With its stuccoed ornamental facade and handsome courtyard, this grand palazzo is a fine example of 16th-century Mannerist architecture. Upstairs, a small four-room gallery houses the Spada family art collection with works by Andrea del Sarto, Guido Reni, Guercino and Titian, while downstairs Francesco Borromini's famous optical illusion, aka the Prospettiva (Perspective), continues to confound visitors.

![]() oChiesa del GesùCHURCH

oChiesa del GesùCHURCH

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 69 7001; www.chiesadelgesu.org; Piazza del Gesù;

%06 69 7001; www.chiesadelgesu.org; Piazza del Gesù; ![]() h7am-12.30pm & 4-7.45pm, St Ignatius rooms 4-6pm Mon-Sat, 10am-noon Sun;

h7am-12.30pm & 4-7.45pm, St Ignatius rooms 4-6pm Mon-Sat, 10am-noon Sun; ![]() gLargo di Torre Argentina)

gLargo di Torre Argentina)

An imposing example of Counter-Reformation architecture, Rome's most important Jesuit church is a fabulous treasure trove of baroque art. Headline works include a swirling vault fresco by Giovanni Battista Gaulli (aka Il Baciccia), and Andrea del Pozzo’s opulent tomb for Ignatius Loyola, the Spanish soldier and saint who founded the Jesuits in 1540. St Ignatius lived in the church from 1544 until his death in 1556 and you can visit his private rooms to the right of the main building in the Cappella di Sant’Ignazio.

The church, which was consecrated in 1584, is fronted by an impressive and much-copied facade by Giacomo della Porta. But more than the masonry, the real draw here is the church's lavish interior. The cupola frescoes and stucco decoration were designed by Baciccia, who also painted the hypnotic ceiling fresco, the Trionfo del Nome di Gesù (Triumph of the Name of Jesus).

In the northern transept, the Cappella di Sant’Ignazio houses the tomb of Ignatius Loyola. The altar-tomb, designed by baroque maestro Andrea Pozzo, is a sumptuous marble-and-bronze affair with lapis lazuli–encrusted columns, and, on top, a lapis lazuli globe representing the Trinity. On either side are sculptures whose titles neatly encapsulate the Jesuit ethos: to the left, Fede che vince l'Idolatria (Faith Defeats Idolatry); and on the right, Religione che flagella l'Eresia (Religion Lashing Heresy).

Museo Nazionale Romano: Crypta BalbiMUSEUM

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %06 3996 7700; www.coopculture.it; Via delle Botteghe Oscure 31; adult/reduced €7/3.50;

%06 3996 7700; www.coopculture.it; Via delle Botteghe Oscure 31; adult/reduced €7/3.50; ![]() h9am-7.45pm Tue-Sun;

h9am-7.45pm Tue-Sun; ![]() gVia delle Botteghe Oscure)

gVia delle Botteghe Oscure)

The least known of the Museo Nazionale Romano's four museums, the Crypta Balbi sits over the ruins of several medieval buildings, themselves set atop the Teatro di Balbo (13 BC). Archaeological finds illustrate the urban development of the surrounding area, while the museum's underground excavations, which can currently be visited only by guided tour, provide an interesting insight into Rome's multilayered past.

Jewish GhettoAREA

(

MAP

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() gLungotevere de’ Cenci)

gLungotevere de’ Cenci)

Centred on lively Via Portico d’Ottavia, the Jewish Ghetto is a wonderfully atmospheric area studded with artisan studios, vintage clothes shops, kosher bakeries and popular trattorias.

Rome’s Jewish community dates back to the 2nd century BC, making it one of the oldest in Europe. The first Jews came as business envoys, with many later arriving as slaves following the Roman wars in Judaea and Titus' defeat of Jerusalem in AD 70. Confinement to the Ghetto came in 1555 when Pope Paul IV ushered in a period of official intolerance that lasted, on and off, until the 20th century. Ironically, though, confinement meant that Jewish cultural and religious identity survived intact.

Monti, Esquilino & San Lorenzo

1Sights

5Eating

3Entertainment