15

15

FAIRY RINGS AND FAIRY TALES

15

15

FAIRY RINGS AND FAIRY TALES

You demi-puppets that

by moonlight do the green sour ringlets make,

Whereof the ewe not bites . . .

SHAKESPEARE, The Tempest

And I serve the fairy queen,

To dew her orbs upon the green

SHAKESPEARE, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

I magine that you are a shepherd leading your flock of sheep and goats to good grazing ground on the high downs in southern England 350 years ago. In the fresh morning light, on the dew-covered downs, you come upon a sight new to your eyes and wondrous to your mind. A large sweeping circle of small mushrooms is fruiting along the outer edge of a grassy ring. The inside of the ring seems trampled; the grass is patchy and sparse with areas of almost bare ground. The rim of the circle, where the mushrooms peer above the grass blades, is just the opposite. Here the grass is growing more luxuriantly than in any of the surrounding area—tall, dense, and with a deeper green hue than the surrounding turf. You are certain that you have been past this spot before and have never seen this remarkable sight. It is as if some magic were at work. Could this be one of those fairy rings your grandfather has told you about? Quickly you gather the sheep into a tighter knot lest one stray into the circle seeking that rich grass. Your grandfather has told tales of the fate that awaits man or beast wandering onto such a fairy-blessed place.

There are certain experiences that serve to remind us all that there is an organizing force overseeing the universe, no matter what your religious affiliation. The thrill of coming upon a large fairy ring of mushrooms fruiting in the middle of a lawn or field is one of those moments for me. The almost unnaturally rich, tall, green grass surrounding a center of scrabbly grass and bare ground is equally thrilling. It’s no surprise that fairy rings have inspired awe, myth, and mystery throughout time and around the world.

Simply put, a fairy ring is a group of mushrooms sprouting together in an easily discernable circular pattern. The rings or arcs can range in size from a few inches to several hundred meters and are found all over the world in areas of temperate or subtropical climate. The largest known ring—located in France and created by the growth of the fungus Clitocybe geotropa—is more than a half mile in diameter and thought to be as much as 800 years old. It is common to see fairy rings that are 10–20 feet in diameter in lawns, ball fields, and parks.

The rings, or sweeping arcs of interrupted rings, are easiest to see on tended lawns or hay fields and are less obvious in pastures or in the woods. Fairy rings of mature mushrooms sometimes can be found in forests, especially when made up of larger fruiting species such as the fly amanita, giant puffballs, or white Clitocybe growing on smooth conifer needle duff. (See #16 in the color insert.)

Before scientists developed a good understanding of the fungus life cycle and growth patterns, many explanations—mundane, fantastical, and supernatural—were put forth in an effort to explain the strange and striking presence of fairy rings in our midst. Here are some of the better known beliefs associated with fairy rings around the world.

In a number of regions in England and continental Europe, it’s said that fairy rings appear in places where the fairy folk meet, hold their balls, and dance. The mushrooms that appear around the edge of the rings are resting seats for the tired fairies. In Sussex, England, fairy rings were called hag tracks, while in Devon it was believed that fairies would catch young horses in the night and ride them round in circles. Also in England, it was long thought that the dew on the lush grass at the edge of the fairy ring was collected by country lasses and purported to improve the complexion, or used as the base of a love potion. In Denmark, elves traditionally have been blamed for the rings and in Sweden, a person entering a fairy ring passes entirely under the control of the fairies. The Germans and Austrians believed the bare patch in the center of the ring is where a fire dragon rested after his nightly wanderings. In many regions, it was thought that fairy rings marked the location of treasure, which could not be secured without the help of the fairies.1,2,3,4

And here in the United States, The Monadnock-Ledger of Jaffrey, New Hampshire, supposedly reported a large fairy ring found during the summer of 1965 and attributed its presence to having been left behind by a flying saucer. That same summer, sightings of UFOs were reported from the nearby the town of Exeter, New Hampshire.

Natural phenomena also have been used to explain fairy ring formation. Over time, people have attributed them to ants, termites, and moles, cow or horse urine, the result of haystack placement, and the action of thunder and lightning. In 1791, Erasmus Darwin in his epic poem The Botanic Garden postulated that the causal agent was “cylindrical lightning” that burned the grass in a circular pattern and was responsible for the resulting increase in soil fertility. Darwin wrote: “So from dark clouds the playful lightning springs, Rives the firm Oak or prints the Fairy Rings.”5

We now know that fairy rings result from the unrestrained growth of fungal mycelium through its grassy growing medium and the equally unrestrained fruiting of the fungus along the outer rim of the ring of growth. Consider a pair of spores of a mushroom such as the meadow mushroom, Agaricus campestris, or fairy ring mushroom, Marasmius oreades, germinating in an open grassy field. These mushrooms are saprobes that feed off the dead grass blades and roots in the top layers of the soil. Once the spores germinate, the hyphae begin to grow outward and, in the absence of any breaks in the continuity of the food source and moisture, the network of hyphae will grow and feed its way through the grass duff at an equal rate in all directions.

Once established, the rate of fairy ring growth can average 5 to 9 inches per year depending on the consistency and amount of rainfall. If the fungus produces mushrooms the first year, it likely would be a small cluster at the point of origin, and any increased growth of the grass could be easily passed off as a result of animal defecation in the absence of fruiting mushrooms.

As the mycelium grows outward, the area of maximal feeding moves outward as the mycelium encounters new organic matter, and the interior portion of the expanding circle becomes depleted of nutrients. The soil in the center of the ring is therefore less fertile and the grass there looks stunted with bare patches of ground. (This retarded grass growth also has been attributed to the mat of mycelium blocking the uptake of water into the soil.) Along the leading edge of the ring, the fungus is actively “feeding”—breaking down the dead plant matter into basic nutrients. With more available nutrients, the grass grows more luxuriantly than either the grass inside or beyond the growth of the fairy ring. It is unusual for a patch of ground to be perfectly homogeneous and free of obstacles; therefore it’s unusual to see a fairy ring of any size that isn’t interrupted in some way. Most grow out as one-sided arcs or curved lines and others become misshapen as one area grows at a different rate than another due to variations in soil moisture, food availability, rocks, ledges, or other factors.

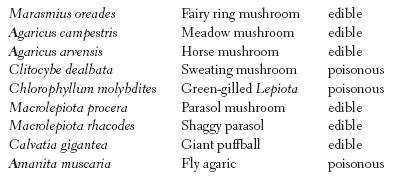

Mushrooms Commonly Found in Fairy Rings

As a mycophile always in pursuit of good edibles to grace my table, I seek out fairy rings as both a curiosity and a potential source of food. Although I know that some mushrooms growing in fairy rings are toxic, many are edible, so I keep an eye out for the lush grass growth in summer and fall that tells me I might find some mushrooms when they’re fruiting.

When I look through the literature and on the Internet for information about fairy rings, I’m somewhat surprised and amused at the number of references to them as a disease of lawn and landscape. There are how-to Web sites devoted to ridding well-tended lawns of this troublesome scourge. (I am constantly amazed at the lengths some people will go to in pursuit of the perfect-looking lawn.) The remedy generally involves intensive aeration, application of herbicides (often not effective), extra nitrogenous fertilizer to mask both the bare spots and the lush growth and, if all else fails, the removal and replacement of the topsoil in an “infected” area. Seems like a whole lot of work to kill off a fascinating backyard exhibition of fungal growth and a source of potentially edible mushrooms. Besides, if we rid ourselves of the fairy rings, where will the poor fairies dance?

THE FAIRY RING MUSHROOM

OR SCOTCH BONNET

(Marasmius oreades)

This is the best known among the many mushrooms that are capable of forming fairy rings (hence the common name) and is a regular sight in almost any grassy area that isn’t overly fertilized and manicured. Evidence of the rings is common throughout the growing season in the form of expanding bands or rings of stimulated green growth at the leading edge and retarded growth inside the ring or arc. Mushrooms fruit throughout the growing season, but most predictably in early summer and again in the early autumn in the Northeast and similar climates. I find it easiest to spot the lush green growth of the ring in late spring or mid- to late autumn.

DESCRIPTION

The common name Scotch bonnet comes from the typical shape of the mushroom’s cap. In the early stages, it is rounded and develops a distinctive broad central knob called an umbo on the cap as it opens fully. The caps and gills are generally the same color, off white to pale tan and darkening to tan with age or repeated “rehydration resurrections,” which refers to a mushroom’s ability to dry out and then return to a fully active moist state when wet weather returns. (See more on this below.) The surface of the cap is bald and smooth without any scales, hairs, or slipperiness. The gills are free to attached (but never decurrent), broad, and widely spaced. The spore print is creamy white.

ECOLOGY

The mycelium of the fairy ring mushroom can remain dormant for long periods of time as it awaits the proper moisture conditions for growth. Because it has evolved as a persistent perennial in a favored environment, you often can count on the Scotch bonnet to fruit yearly or several times yearly over many years.

One fascinating feature of this mushroom is its ability to produce fruiting bodies that are capable of completely drying out, only to rehydrate later and continue to grow and produce new spores. For a mushroom that grows and fruits on open grassland under the full onslaught of the Sun and faces the vagaries of intermittent rain showers, this represents a great reproductive advantage. For years, observers were aware of this rehydrating ability, but scientists were unsure whether spore production and cell division continued after the mushroom dried out; in other words, it was unclear whether the mushroom truly remained alive when rehydrated. More recent observations and studies have confirmed that this is indeed the case. The mushroom remains alive, though inactive, when it’s desiccated and returns to full active spore production when it rehydrates. Scientists have been working toward a better understanding of the mechanisms that allow living organisms to seemingly return to life following this “rehydration resurrection.”

Sea monkeys are perhaps the best-known example of rehydration resurrection. They arrive in the mail as a packet of powder that is actually a herd of encysted brine shrimp—tiny shrimp-like crustaceans native to salt ponds and salt flats all over the world—that, due to the feast-or-famine water cycle of their natural environment, have evolved adaptations that enable them to go into “suspended animation” or dormancy when their desert environment dries up. During the encysted state, there are no measurable signs of life and they can survive for long periods of time, enduring extreme temperatures both hot and cold. But sea monkeys quickly return to normal functioning when salt water is added to the powder.

Resurrection ferns and other such ferns exhibit similar patterns in feast-or-famine environments where there is not enough moisture. I remember the first time I collected the fronds of the Stanley’s cloak fern in the foothills of the Sandia Mountains outside of Albuquerque, New Mexico. These ferns grow in microclimates created by overhanging granite ledges or under the protection of huge granite boulders where any rain that falls flows off the rock into these protected oases. Growing at an altitude of 6,500 feet in an area that receives less than 10 inches of rain per year, the small fronds of these ferns curl up upon drying into tight ball-like clusters with powdery white, waxy undercoated surfaces facing out. In times of wet weather, the fronds unfold and photosynthesis begins anew.

Studies of organisms able to manage rehydration resurrection, including fairy ring mushrooms, show that as they dry out there is an increase in the production of certain sugars such as trehalose. As the dried organisms rehydrate and reactivate, they consume the trehalose. It seems that the increased levels of these sugars play a significant role in preserving the integrity of cell walls as the tissue dries.6 Studies confirm that the fairy ring mushroom has been shown to increase and decrease levels of trehalose as it dries out and rehydrates.

LOOK-ALIKES

There are a few mushrooms that grow in grassy areas and can resemble fairy ring mushrooms. A few brown-black spored members of the Panaeolus or Psilocybe genera prefer this habitat, so avoid any mushrooms without off-white gills. The poisonous sweating mushroom, Clitocybe dealbata, also grows in grass and easily can grow along with the fairy ring mushroom. It has a dirty-white cap and closely spaced white gills attached to a white stem or slightly decurrent. The sweating mushroom contains muscarine and will produce markedly unpleasant symptoms, including copious sweating, tearing, and salivating within thirty minutes in anyone who has eaten it.

CAVEATS

Because fairy ring mushrooms thrive in domesticated lawns, there are a couple of specific caveats regarding their collection for food. I have made the mistake of not collecting this mushroom several times, thinking I would return in a day or so to gather the bounty. There were two mistakes in that assumption; the first had to do with the unfortunate habit we suburbia dwellers refer to as mowing the lawn. Uncountable delectable mushrooms succumb to those rapacious whirling metal blades each season. The second mistake was perhaps more pernicious and had to do with other alert mushroom collectors (including many who have learned the art at one of my classes) getting the bounty ahead of me. The final caveat involves the reality that, like many other mushrooms, the fairy ring mushroom is able to absorb and retain some pesticides and heavy metals. This mushroom grows best in unpampered lawns anyway, so avoid collecting them from a well-manicured lawn where there is a good chance that chemical treatments have been in use.

EDIBILITY

Marasmius oreades is considered by many mushroom fanciers to be a good to choice edible. Though small in size, it is common to find many individual fruiting bodies in an arc or fairy ring, so a sizable quantity can be collected on a good day. The tough fibrous stem is best removed, as it doesn’t add much to the quality of the dish. I find that if I pinch the upper stem between my thumbnail and first finger, the cap will easily and cleanly pop off the stem. David Arora suggests bringing scissors along when collecting for clean stemless Scotch bonnets. Not surprisingly, given its ability for rehydration ressurection, M. oreades dries easily and drying is the preferred method of preservation. This is one mushroom I wouldn’t hesitate to collect in a semidry state. The fairy ring mushroom cap is the perfect size and shape to use whole in a number of dishes. Several years ago I used a jar full of dried caps in a Thanksgiving bread stuffing for our holiday turkey to great reviews. Cooked, this mushroom retains a chewy texture and has a mild distinct flavor, making it a welcome addition to many dishes.

Fairy rings present us with an opportunity to meditate on the wonder and the intricacy of the natural world. They also offer a phenomenal opportunity to teach children about nature and the life cycle, ecology, and mythology of these fascinating fungi. Fairy rings can be formed by a number of mushrooms, and in every instance they evoke a whiff of magic.

Of airy elves, by moonlight shadow seen,

The Silver token and the circled green.

ALEXANDER POPE, Rape of the Lock, 1712