13

caffeine in the laboratory

After the fall of Rome, the sciences originated by the Greeks lay quiescent for more than a millennium, eventually falling under the spell of such alchemical adepts as Albertus Magnus (1193–1280) and Philippus Aureolus Paracelsus (1490–1541). These sciences were quickened in Restoration England by the members of one of the oldest and most important coffee klatches in history, the Royal Society. Still one of the leading scientific societies in the world, the Royal Society began in 1655 as the Oxford Coffee Club, an informal confraternity of scientists and students who, as we said earlier, convened in the house of Arthur Tillyard after prevailing upon him to prepare and serve the novel and exotic drink. To appreciate the audaciousness of the club members, we must remember that coffee was then regarded as a strange and powerful drug from a remote land, unlike anything that had ever been seen in England. It was not, at first, enjoyed for its taste, as it was brewed in a way that most found bitter, murky, and unpleasant, but was consumed exclusively for its stimulating and medicinal properties. The members of the Oxford Coffee Club took their coffee tippling to London sometime before 1662, the year they were granted a charter by Charles II as the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge.

Historical reflection on changing fashions in drug use might justify the saying, “By their drugs you shall know them.” Members of the Sons of Hermes, the leading alchemical society of the Middle Ages, experimented with plants and herbs, almost certainly including the Solanaceæ family, commonly known as nightshades, which comprises thorn apple, belladonna, madragrora, and henbane.1 These plants contain the hallucinogenics atropine, scopolamine, and hyoscyamine, which were used historically as intoxicants and poisons and more recently as “truth serums.” These drugs often produce visions, characteristically inducing three-dimensional psychotic delusions, often populated with vividly real people, fabulous animals, or otherworldly beings. Because of atropine’s ability to bring about a transporting delirium, witches rubbed an atropine-laced ointment into their skin to induce visions of flying. Obviously, the Solanaceæ drugs are as well-suited to the fabulous, symbolic, magical, transformational doctrines of alchemy as caffeine is to the rational, verifiable, sensibly grounded, and literal endeavors of modern science.

It may therefore not be entirely adventitious that the thousand-year lapse of European science in the Middle Ages, during which naturalism commingled promiscuously with magic, ended at the same time that the first coffeehouses opened in England and that coffee, fresh from the Near East, became suddenly popular with the intellectual and social avant-garde in Oxford and London. The aristocratic Anglo-Irish Robert Boyle (1627–91), the father of modern chemistry, regarded in his time as the leading scientist in England, was a founding member of the original Oxford Coffee Club. Credited with drawing the first clear line between alchemy and chemistry, Boyle formulated the precursor to the modern theory of the elements, achieving the first significant advance in chemical theory in more than two thousand years.2 Within a few years after the English craze for caffeine began, the modern revolutions, not only in chemistry, but in physics and mathematics as well, were well under way. Twentieth-century scientific studies suggest that caffeine can increase vigilance, improve performance, especially of repetitive or boring tasks such as laboratory research, and increase stamina for both mental and physical work. In consequence of its avid use by the most creative scientists of the second half of the seventeenth century, caffeine may well have expedited the inauguration of both modern chemistry and physics and, in this sense, have been the only drug in history with some responsibility for stimulating the formulation of the theoretical foundations of its own discovery.

Caffeine and Chemistry

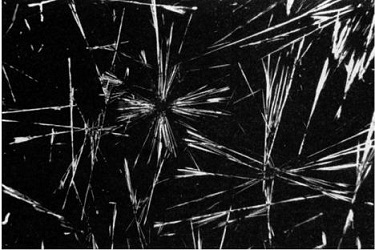

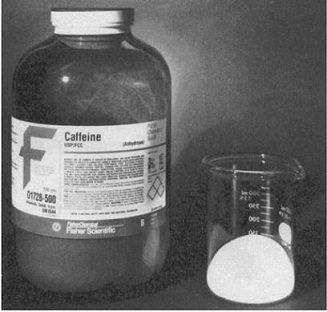

Caffeine is a chemical compound built of four of the most common elements on earth: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen. The pure chemical compound is collected as a residue of coffee decaffeination, recovered from waste tea leaves, produced by methylating the organic compounds theophylline or theobromine, or synthesized from dimethylurea and malonic acid. At room temperature, caffeine, odorless and slightly bitter, consists of a white, fleecy powder resembling cornstarch or of long, flexible, silky, prismatic crystals. It is moderately soluble in water at body temperature and freely soluble in hot water. Caffeine will not melt; like dry ice, it sublimes, passing directly from a solid to a gaseous state, at a temperature of 458 degrees Fahrenheit.3

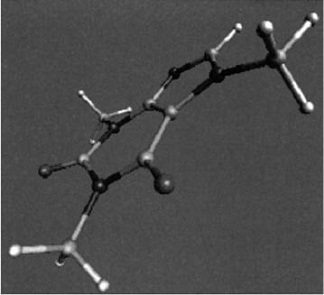

A computer-generated model of the caffeine molecule.

The formula for caffeine is C8H10N4O2, which means that each caffeine molecule comprises eight atoms of carbon, ten atoms of hydrogen, four atoms of nitrogen, and two atoms of oxygen. However, to understand the structure and properties of caffeine, or of any chemical compound, it is necessary not only to identify its atomic constituents but also to describe the way in which these constituents fit together. A compound’s chemical name articulates this chemical structure and serves to designate how its parts are arranged and connected. Caffeine has several chemical names, or alternative ways of representing its structure, the most common of which is 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine. The name revealing its structure most fully is 1H-Purine-2,6-dione, 3,7-dihydro-1,3,7-trimethyl. Other chemical designations for caffeine include:

1,3,7-Trimethyl-2, 6-dioxopurine

7-Methyltheophylline

Methyltheobromine

To understand the way in which these names represent caffeine’s structure, it is helpful to consider them in the context of the structural descriptions of caffeine’s parent compound, purine, and of caffeine’s isomers, or close relations.

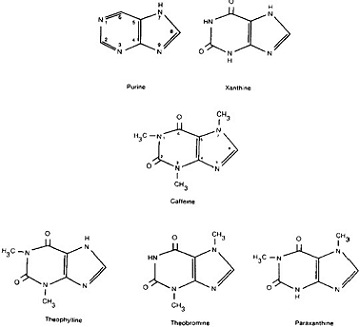

Caffeine is one of a group of purine alkaloids, sometimes called methylated xanthines, or simply, xanthines. Other methylated xanthines include theophylline, theobromine, and paraxanthine. All three are congeners, or chemical variations, of caffeine, and all three are primary products of caffeine metabolism in human beings. Purine itself is an organic molecule composed entirely of hydrogen and nitrogen. All purine bases, including caffeine, are nitrogenous compounds with two rings in the molecules, five- and six-membered, each including two nitrogen atoms. The purine alkaloid xanthine is created when two oxygen atoms are added to purine.

The other purine alkaloids, in turn, are built out of xanthine by adding methyl groups, that is, groups of one carbon and three hydrogen atoms, in varying numbers and positions. For example, caffeine, a trimethylxanthine, the most common methylxanthine in nature, is xanthine with three added methyl groups, in the first, third, and seventh positions. Similarly, theophylline (1,3-dimethylxanthine) consists of xanthine with methyl groups in the first and third positions, theobromine (3,7-dimethylxan-thine), consists of xanthine with methyl groups in the third and seventh positions, and paraxanthine (1,7-dimethylxanthine) consists of xanthine with methyl groups in the first and seventh positions. Because the body transforms caffeine into each of these isomers, they may well play a part in caffeine’s health effects.

Although purine itself does not occur in the human body, chemicals in the purine family are widely present there as throughout nature. In fact, in addition to being the parent compound of caffeine and other methylxanthines, purine is the parent compound of adenine and guanine, two of the four basic constituents of the nucleotides that form RNA and DNA, the molecular chains within the cells of every living organism that determine its genetic identity. Some scientists have speculated that, because of this similarity to genetic material, caffeine and its metabolites may introduce errors into cell reproduction, causing cancer, tumors, and birth defects. As of this writing, there is no credible evidence to substantiate such fears.

The molecular structure of caffeine and related compounds.

The Metabolism of Caffeine: From Cup to Bowl, or A Remembrance of Things Passed

Because caffeine is fat soluble and passes easily through all cell membranes, it is quickly and completely absorbed from the stomach and intestines into the blood-stream, which carries it to all the organs. This means that, soon after you finish your cup of coffee or tea, caffeine will be present in virtually every cell of your body. Caffeine’s permeability results in an evenness of distribution that is exceptional as compared with most other pharmacological agents; because the human body presents no significant physiological barrier to hinder its passage through tissue, the concentrations attained by caffeine are virtually the same in blood, saliva, and even breast milk and semen.

Caffeine’s stimulating effects largely depend on its power to infiltrate the central nervous system. This infiltration can only be accomplished by crossing the blood-brain barrier, a defensive mechanism that protects the central nervous system from biological or chemical exposure by preventing large molecules, such as viruses, from entering the brain or its surrounding fluid. Even following intravenous injection, many drugs fail to penetrate this barrier to reach the central nervous system, while others enter it much less rapidly than they enter other tissues. One of the secrets of caffeine’s power is that caffeine passes through this blood-brain barrier as if it did not exist.

Photomicrographs of caffeine crystals at a magnification of 28x. (Photograph taken by Paul Barrow at BioMedical Communications, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, © 1999 Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K.Bealer.)

The maximum concentrations of caffeine in the body, including in the blood circulating in the brain that is responsible for caffeine’s major stimulating effects, is typically attained within an hour after consumption of a cup of coffee or tea. Absorption is somewhat slower for caffeine imbibed in soft drinks. It is important to remember that the concentration of caffeine in any person’s body is a function not only of the amount of caffeine consumed but of the person’s body weight. After drinking a cup of coffee with a typical 100 mg of caffeine, a 200-pound man would attain a concentration of about 1 mg per kilogram of body weight. A 100-pound woman would attain about 2 mg per kilogram and would therefore (all other metabolic factors being considered equal) experience double the effects experienced by the man.

What becomes of all this ambient caffeine permeating your cells?

Factors Affecting Rate of Caffeine Metabolism in Humans

| Slows Metabolism | Speeds Metabolism |

| alcohol | cigarettes |

| Asian | Caucasian* |

| man | woman |

| newborn | child |

| oral contraceptives | |

| liver damage | |

| pregnancy |

Note: A Japanese non-smoking man who was drinking alcohol with his coffee would probably feel the effects of caffeine about five times longer than would an Englishwoman who smoked cigarettes but did not drink or use oral contraceptives. If the man had liver damage, the difference could be even more dramatic. Remember this variability the next time you hear apparently contradictory reports from your friends about what caffeine does to them.

*Richard M.Gilbert, Caffeine: The Most Popular Stimulant, p. 62.

Caffeine and most other chemical compounds you ingest ultimately make their way to the liver, the body’s central blood purification factory. The bloodstream carries caffeine from the stomach and intestines, throughout the body, and, by means of the hepatic portal vein, through the liver. There it is metabolized, or converted into secondary products, called “metabolites,” which are finally excreted in the urine. More than 98 percent of the caffeine you consume is converted by the body in this way, leaving the remainder to pass through your system unchanged.

Caffeine’s biotransformation is complex, producing more than a dozen different metabolites. The study of these transformations in human beings has been impeded by the fact that the metabolic routes for caffeine demonstrate a remarkable variety among different species. This means that experiments with rats, mice, monkeys, and rabbits, for example, are of limited value in advancing our knowledge of what happens to caffeine in human beings. However, over the past two decades, sophisticated techniques for identifying the components of the caffeine molecule, distinguishing them from very similar compounds, and tracing the fate of caffeine in the body have revealed the human metabolic tree in considerable detail.

These extensive studies disclose that the liver accomplishes the biotransformation of caffeine in two primary ways:

- Caffeine, a trimethylxanthine, may be “demethylated” into dimethylxanthines and monomethylxanthines by being stripped of either one or two of its three methyl groups.

- Caffeine may be oxidized and converted to uric acids. This means that an oxygen atom is added to the caffeine molecule.

The first of these mechanisms predominates, with the result that the principal metabol ites of caffeine found in the bloodstream are the dimethylxanthines: paraxanthine, into which more than 70 percent of the caffeine is converted, theophylline, and theobromine. Paraxanthine is thus a sort of second incarnation of caffeine.

Although there are multiple alternative paths by which caffeine is metabolized in human beings, all of these pathways end in one or another uric acid derivative, which is then excreted in the urine. Complicating this picture is the fact that the profile of urinary metabolites, that is, the relative mix of the final metabolic products, exhibits marked variation among individuals, with differences observed as between children and adults, smokers and non-smokers, women who are taking oral contraceptives and those who are not.

An additional complicating factor is the fact that chemical metabolism can present cybernetic dynamics, which in this case means that the very process of metabolizing a methylxanthine can alter the speed at which additional amounts of methylxanthines will be metabolized. For example, it has been shown that the methylxanthine theobromine, a constituent of cacao and one of the primary metabolites of caffeine, is a metabolic inhibitor of theobromine itself, of theophylline, and possibly of caffeine as well. Studies reveal that daily intake of theobromine decreases the capacity to eliminate methylxanthines. This could mean, for example, that if you regularly eat chocolate, coffee or tea may keep you awake longer. Conversely, subjects on a methylxanthine-free diet for two weeks increased their capacity to eliminate theobromine. The fact that asthma patients being treated with theophylline need careful monitoring and frequent dosage adjustments is probably a result of these cybernetically governed variations in methylxanthine metabolism.

One of the challenges faced by researchers attempting to analyze any chemical compound’s health effects is the fact that a drug’s metabolites often have more significant effects than did the original drug itself. Scientists are still unsure as to what degree and in what respects caffeine’s metabolites are responsible for its effects, although most would agree that its methylxanthine products contribute to the physical and mental stimulation that is a hallmark of caffeine consumption.

Caffeine gets in and out of your body quickly. The same high solubility in water that facilitates its distribution throughout the body also expedites its clearance from the body. Because caffeine passes through the tissues so completely, it does not accumulate in any body organs. Because it is not readily soluble in fat, it cannot accumulate in body fat, where it might otherwise have been retained for weeks or even months, as are certain other psychotropic drugs such as marijuana. Because caffeine also demonstrates a relatively low level of binding to plasma proteins, its metabolism is not prolonged by the sequential process by which, in chemicals that are highly bound, additional amounts dissociate from the protein as the unbound fraction is excreted or metabolized, extending the active life of the drug in the body.

The degree to which a drug lingers in the body, its kinetic profile, is quantified by what physiologists call its “half-life,” the length of time needed for the body to eliminate one-half of any given amount of a chemical substance. For most animal species, including human beings, the mean elimination half-life of caffeine is from two to four hours, which means that more than 90 percent has been removed from the body in about twelve hours. However, the observed half-life can be influenced by several factors and therefore demonstrates considerable individual and group variation. For example, women metabolize caffeine about 25 percent faster than men. But if women are using oral contraceptives, their rate of caffeine metabolism is dramatically slowed. In addition, pregnancy results in a considerable increase the half-life with a concomitant increase in exposure by the fetus.4 Because caffeine is metabolized in the liver, hepatic impairment will also slow caffeine’s metabolism. Newborn infants are dramatically less capable of metabolizing caffeine than are adults, probably because their livers are unable to produce the requisite enzymes, an incapacity that extends the drug’s half-life in them to eighty-five hours. Some studies suggest that many other factors, including the use of other drugs, can raise or lower the metabolic rate from the mean value. For example, cigarette smoking doubles the rate at which caffeine is eliminated, which means that smokers can drink more coffee and feel it less than nonsmokers. Drinking alcohol slows the elimination rate, which means that drinkers feel the caffeine in their coffee more than non-drinkers.5 Research has even suggested that the rate of caffeine metabolism varies among the races, based on findings that Asians metabolize the drug more slowly than Caucasians.6

Relative Half-Life of Caffeine

| Subject | Half-Life (in hours) |

| Healthy adults | 3 to 7.5 (mean, 3.5) |

| Pregnant women | <18 |

| Preterm infants | 65 to 100 |

| Term infants | 82 |

| 3- to 4.5-month-olds | 14.4 |

Adapted from Drug Facts and Comparisons, p. 928.

These metabolic findings help us to understand the strong social association between cigarettes and coffee. We picture the writer at his word processor, drinking big mugs of strong coffee as he puffs away at an endless sequence of smokes. We also imagine the typical coffeehouse habitué, gesticulating in a cloud of smoke as he converses with his fellow coffee drinkers. These images make sense. Heavy smokers, to achieve the same stimulating effects, would have to drink far more coffee than non-smokers. See part 5 of this book, “Caffeine and Health,” for a full discussion of how heavy caffeine use may delay or prevent some of the serious lung complications that can result from smoking, which would constitute an additional strong bond between the two.

The metabolic profile of caffeine may also help to account for the common attempt to use caffeine to combat the effects of alcohol. It is true that the degree of alcohol intoxication is a function of the alcohol level in the blood, a level that cannot be altered by caffeine. However, caffeine, because it is felt more persistently by those who are drinking alcohol, may in fact have a more sustained stimulating effect and in this way help the drinker dissipate the grogginess that is associated with excess boozing.7

The French essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533–92) did not trust physicians because he thought that each person, knowing himself best, is the best judge of the conditions conducive to his own health. Today nearly everyone agrees that good medical doctors and their expert care are indispensable for well-being. Nevertheless, even our quick review of the variability and complexity of caffeine’s metabolism suggests that, whatever the general profile of its behavioral and physical effects, each person must consider his own personal and medical history in order to understand how caffeine might affect him.

Mechanism of Action: Caffeine Kicks In

Most caffeine advocates and many caffeine opponents agree that caffeine helps to keep a person awake, increases energy, improves mood, and enhances the ability to think clearly In an effort to discover how and to what degree caffeine does these and other things, scientists have investigated it more extensively than any other drug in history. Central to the long-standing debate over health concerns about the use of coffee and tea was the question of how these drinks do what they do, that is, what caffeine’s mechanism of action in the human body is. The Russo-Swiss scientist Gustav von Bunge, a late-nineteenth-century professor at Basel University, who originated the concept of the hematogen in 1885, authored a precursor of contemporary theories. Bunge hypothesized that an unconscious longing of the body to increase its stores of xanthine, a substance present in small quantities in all tissues, was satisfied by caffeine, because of their chemical similarity.8 Although this explanatory mechanism is fanciful by today’s scientific standards, it does recognize caffeine’s membership in the xanthine family and attempts to tie its action to the functions of related compounds naturally occurring in the body.

In approaching the question of how caffeine works, scientists today are confronted with the complex circumstance that the drug produces an effect, and in certain instances more than one effect, on the cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, and central and peripheral nervous systems. Partly as a consequence of this complexity, no one has identified caffeine’s mechanism of action with any certainty. Particularly unclear are the sources of its psychostimulant and cardiovascular effects.

A good way to begin our inquiry into the possible mechanisms underlying caffeine’s effects is to briefly consider the ways other stimulants, such as amphetamine and cocaine, have been understood to operate.

Stimulants seem to work in one of two ways, as agonists or antagonists. Agonists are substances that aid drug or bodily processes by increasing or decreasing the production or effectiveness of hormones or neurotransmitters that, through the modulation of neuromediators, cause nerve cells to fire more frequently and more energetically. Antagonists, or agents that work to reduce the action of drug or bodily processes, augment or diminish the uptake of neurotransmitters that, had they been allowed to reach their uptake sites, would have caused the nerve cells to fire more or less frequently or energetically. In rough laymen’s terms, the stimulants in the first group help you generate or utilize a charge of energy, while those in the second group delay the dampening or dissipation of whatever energy is already circulating.

Amphetamine and methamphetamine work in the first of the ways described above. Amphetamines are essentially artificial adrenaline, and, when they circulate in the bloodstream, all the effects of increased adrenaline production are experienced. Amphetamine exerts most of its central nervous system (CNS) effects by releasing nitrogen-containing organic compounds, or amines, from their storage sites in the nerve terminals. Its analeptic, or alerting, effect and a component of its muscle-stimulating action are thought to be mediated by the release of the hormone norepinephrine by the brain. Other components of motor stimulation and the stimulating effects of amphetamine are probably caused by the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Cocaine works in the second way. Where amphetamine stimulates increased production of a neurotransmitter such as dopamine, cocaine achieves many reinforcing effects by inhibiting the uptake of dopamine by the neurons. Both mechanisms result in increased concentrations of dopamine at the synapses, or junctures connecting the neurons.

Although the use of stimulants in both categories can be self-reinforcing, only stimulants that depend for their effects on the first mechanism tend to produce tolerance and physical dependence, two major clinical manifestations of addiction. Stimulants that depend for their effects on the second mechanism tend to remain effective at or near the original dose, and, although they may produce psychical habituation, that is, a strong mental craving, they do not create a true physical dependence or metabolic tolerance characterized by somatic, or bodily, withdrawal symptoms.

Modern investigations into the pharmacology of caffeine are both intricate and inconclusive. Although techniques have become dramatically more sophisticated in the past few decades and researchers have applied tremendous energies and considerable resources to unraveling the tangled skein of caffeine’s course of action in the human body, the results are not only difficult for a layman to understand but are ambiguous and tentative at best, even when considered by the experts. Three theories have successively enjoyed favor in the last two decades, and two of these three have already been discredited. The fate of the third remains undecided.

The three major theories that have been recently adduced to explain the mechanism of action of caffeine and the other methylxanthines are:

- Calcium mobility theory or the translocation of intracellular calcium;

- Phosphodiesterase inhibition theory, or the mediation by increased accumulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) due to inhibition of phosphodiesterase; and

- Adenosine blockade theory, or the competitive blockade of adenosine receptors.

Calcium Mobility Theory

Inotropic agents are drugs that increase the force of cardiac muscle contraction, thereby tending to increase cardiac output. The most important group of inotropic agents includes digitalis, found in the foxglove plant, which has been used to stimulate the heart muscle in cardiac arrest for hundreds of years. There are several classes of inotropic agents with different mechanisms of action. One type of inotropic agent is caffeine and related methylxanthines, such as theophylline.

Inotropic agents can influence the body’s response to neurotransmitters through affecting the output of neuromediators such as cyclic adenosine 3-, 5-monophosphate, which indirectly increases the influx of calcium ions into the cells, and thereby increases the force of contraction of the heart muscles. An increase in intracellular calcium increases the force of contraction, since intracellular calcium ions are responsible for initiating the shortening of muscle cells.

It now appears that caffeine achieves these effects only at toxic dose levels, from ten to a hundred times greater than those normally consumed in coffee, tea, or soft drinks. Consequently it is virtually impossible that calcium translocation is important in explaining the general effects of dietary caffeine.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibition: The cAMP Cycle of Energy Release

The human body stores energy in the muscles in the form of sugars called “glycogens.” When you need a burst of energy, for example, when you are exercising or when you have delayed eating, glycogen is quickly released and burned as fuel. In the late 1950s, researchers discovered that a hormone called cyclic adenosine monophosphate, or “cAMP,” which mediates the actions of many neurotransmitters and hormones in the nervous system, played a central role in the regulation of glycogen metabolism. It was demonstrated that, by increasing the persistence of cAMP, through a relatively complex process involving the inhibition of another hormone, phosphodiesterase, caffeine prolongs or intensifies the effect of adrenaline and thus enhances the ability of your body to burn glycogen. This mechanism was widely advanced as the mechanism of caffeine’s stimulating action in the body.

However, the effect of caffeine on cAMP is modest, even at concentrations well above typical plasma concentrations in humans. In fact, in order to achieve blood levels of caffeine equal to those in the studies supporting this hypothesis, a 200-pound man would have to drink fifty cups of coffee in a few minutes. Thus, as with the intracellular calcium hypothesis, the mechanism of phosphodiasterase inhibition appears to be of limited importance in explaining the effects of caffeine observed at the levels attained by its ordinary consumption.

Adenosine Blockade: The Newest Theory on the Block

If a neurotransmitter or neuromodulator is to achieve any effect, it must reach the sites designed to accomplish its uptake into the human nervous system. Any substance that blocks this uptake prevents or reduces the effects of the neurotransmitter or neuromodulator it is blocking.

Adenosine is a neuromodulator with mood-depressing, hypnotic (sleep-inducing), and anticonvulsant properties and tends to induce hypotension (low blood pressure), bradycardia (slowed heartbeat), and vasodilatation. It also decreases urination and gastric secretion. Adenosine decreases the rate of spontaneous nerve cell firing and depresses evoked nerve cell potentials in the brain by inhibiting the release of other neurotransmitters that control the excitability, or responsiveness, of central neurons. The newest theory about caffeine’s mechanism of action is that it acts as a competitive antagonist of adenosine; that is, it achieves most of its stimulant effects by blocking the uptake of, and thereby the actions of, adenosine.

To put matters simply, there are only so many receptors where adenosine can “plug itself in” to the nervous system, the way a key fits into a lock. Caffeine counterfeits the key. By doing so, caffeine blocks many of adenosine’s receptors, and thus prevents the body from being affected by adenosine’s depressing and hypnotic effects. The result, according to this theory, which arose in the early 1970s, is that when we ingest caffeine we are unable to become tired or sleepy as we would otherwise have done. This theory holds that caffeine, by inhibiting the actions of adenosine, produces a whole slew of effects which are opposite adenosine’s. Such a mechanism would account, for example, for caffeine’s ability to increase respiration, urination, and gastric secretion.9

The ultimate evaluation of this theory of caffeine’s mechanism of action is complicated by the variety of adenosine receptors and their differing roles in different tissues. However, because, with typical dietary doses of caffeine, blood levels of caffeine are believed to be too low to appreciably affect the non-adenosine mechanisms of action, adenosine antagonism appears to be the primary mechanism for caffeine’s effects. It is not known if these other mechanisms may mediate some of the clinical effects produced when caffeine blood levels are unusually elevated, as may occur in cases of caffeine intoxication. A possible shortcoming of the adenosine blockade theory is that, even though it appears that the blockade of these receptors by caffeine has an important role in its pharmacology, caffeine’s complex effects on behavior may not be fully explicable in terms of this blockade alone.10 For example, alertness is informed by many neurotransmitter systems, only one of which is the noradrenalin system. Because chronic caffeine use effects changes in a number of other neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, acetylcholine, GABA, and the glutamate systems in the brain, it remains for future researchers to determine what part if any these changes play in the behavioral effects associated with caffeine’s use.

The very latest findings suggest that the adenosine story may actually tie caffeine’s mechanism of action to that of other stimulants, such as amphetamines and cocaine, after all. In an unpublished study, Bridgette Garrett and Roland Griffiths maintain that caffeine enhances dopaminergic activity, “presumably by competitive antagonism of adenosine receptors that are co-localized and functionally interact with dopamine receptors. Thus caffeine, as a competitive antagonist at adenosine receptors, may produce its behavioral effects by removing the negative modulatory effects of adenosine from dopamine receptors, thus stimulating dopaminergic activity.”11 If true, this means that caffeine, like amphetamine or cocaine, produces increased synaptic concentrations of dopamine, an explanation consistent with findings that caffeine’s behavioral effects are similar to those of these classic dopaminergically mediated stimulants.

Paradoxes and Problems and Unanswered Questions

A major paradox that arises when we attempt to understand caffeine’s primary effects in terms of its role as an adenosine antagonist, or reuptake inhibitor, is that, were this its only operative mechanism, we would have trouble explaining the development of tolerance and physical dependence. Obviously tolerance, or increasing “resistance” to the drug, which requires caffeine users to progressively augment their dose in order to maintain its stimulant effects, is generally experienced by regular coffee drinkers; and dependence, as defined by the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt cessation of use, seems fairly common as well, and both tolerance and dependence have been well established in the literature.

However, the observation that caffeine produces increases of 10 to 20 percent in the number of brain adenosine receptors has prompted speculation that this increase may be the mechanism underlying withdrawal symptoms. The notion here is that the body is not completely fooled by the invasion of caffeine as an adenosine impostor and creates new receptor sites as compensation. When caffeine intake is reduced or eliminated, these extra sites combine with the original sites to uptake a greater amount of adenosine than is normal, with the result that adenosine’s effects, including sleepiness and depression, are multiplied. Thus, this explanation would help account for many of the withdrawal symptoms produced by the abrupt reduction or cessation of caffeine use.

Unfortunately, there remain some inconsistencies that lead scientists to believe that this explanation is at best incomplete, for it cannot adequately serve to explain the development of tolerance. Tolerance to caffeine can increase to the point where it cannot be overcome by any dose, that is, where it becomes insurmountable, failing to duplicate its former effects in the user regardless of how high a dose is ingested, and there is no easy way to understand how the adenosine blockade theory could be consistent with insurmountable tolerances. In addition, as we have observed in our discussion of cocaine, there is no clear precedent of a competitive antagonist, such as caffeine, losing its potency after chronic administration. And, in fact, caffeine seems to retain its full potency as an adenosine antagonist, even in cases where an insurmountable tolerance to caffeine’s stimulant effects has clearly been achieved. Finally, there seems to be no theoretical basis for expecting that an increase in the number of receptor sites should produce tolerance to the antagonist.

To put it simply, if caffeine’s mechanism of action is explicable in terms of a competitive blockade of adenosine, we might expect withdrawal symptoms upon cessation of use, but we would still lack any explanation for the development of tolerance. Problems like these make it clear how far science still has to go if it is to reveal the secrets of caffeine. Exactly what it does and exactly how it does what it does are still largely unknown. Fortunately, it is possible to assess the effects of caffeine on human health by means of studies that are independent of a detailed knowledge of its underlying mechanisms.

Where the Caffeine Is

Few of us in Western countries today chew the leaves, bark, fruit, or nuts of caffeine-containing plants. We get our caffeine and other methylxanthines from drinks, foods, and pills. In the United States, about 70 percent of our caffeine is found in coffee beans, about 14 percent is found in tea leaves, more than 12 percent is in the form of the crystal caffeine, nearly 3 percent is found in cacao beans, and the remaining fraction from all other sources, including cola nut, maté, and guarana. Chocolate owes some of its stimulating power to the methylxanthine theobromine, and tea contains a small amount of theophylline. The caffeine in cola drinks is not derived from cola nuts, but is a superadded extract from coffee or tea. Caffeine is found in some over-thecounter medications, such as alertness aids and aspirin compounds, and in prescription medications, such as narcotic painkillers, as an adjuvant to their analgesic power.

In Appendix B are a number of charts listing various dietary and medicinal sources, with the amount of caffeine, theobromine, or theophylline found in each.

What Is a Cup?

A figure that is passed around, from one research paper or newspaper article to the next, is that a cup of coffee contains an average of 100 mg of caffeine. This sounds simple and straightforward and suggests that it is fairly easy to determine how much caffeine we are taking in when we have a cup of coffee. Unfortunately, when we scrutinize this figure, many uncertainties arise.

One problem is, exactly how much liquid is in a “cup of coffee”? A big mug or large paper cup, filled to the brim, may be 10 ounces or even 12 ounces or more. If not filled to the brim, a small cup may hold as little as 4 ounces. Amounts often quoted for cups are 5 ounces or 6 ounces, and the cup itself as a standard liquid measure is 8 ounces. So when we speak of a cup, we may be speaking of 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12 ounces or more. Another problem is, how much caffeine is in the coffee, ounce for ounce? This number will vary widely with such variables as method of preparation, type of coffee bean, method of roasting, and amount of coffee used.

The result of multiplying these two uncertainties produces a remarkably wide range for what might constitute the “correct” value for the amount of caffeine in a “cup” of coffee. A small cup of weak instant coffee might have as little as 50 mg. A large cup of infused coffee steeped for a long time with a lot of robusta beans might have 350 mg. Admittedly these are extreme values, but we believe that doses in the range of 100 to 250 mg are common. According to the Food and Drug Administration, a 5-ounce cup of coffee contains 40 to 180 mg of caffeine. Similar problems beset an evaluation of how much caffeine is found in a cup of tea.

Studies profiling the caffeine content of coffee and tea as actually served to restaurant customers or consumed at home are rare. One 1988 Canadian study, published in Food and Chemical Toxicology,12 surveyed almost seventy “preparation sites,” and found considerable differences from place to place and even between one day and the next at the same place. A review of the caffeine content of coffee brewed in almost sixty homes showed levels ranging from about 20 mg to nearly 150 mg per cup, more than a sevenfold variation. Coffee tested in eleven restaurants exhibited similar differences. Further, “decaf” served at restaurants sometimes had substantial amounts of caffeine. Finally, there were large variations in the caffeine content among the seventeen brands of instant coffee, even when prepared under controlled laboratory conditions.

The tests of tea showed a comparable variation in caffeine potency, although, of course, the average levels for tea were lower than those for coffee. According to the Republic of Tea Home Page, the following three factors determine how much caffeine is present in a cup of tea:

- The longer the leaves have been fermented, the greater their caffeine content. Green tea, which is unfermented, has the least caffeine; oolong, which is partially fermented, has about 50 percent more; and black tea, which is fully fermented, has three times as much.

- The longer tea is brewed, the more caffeine is present in the final drink. A cup of black tea infused for three minutes has 20 to 40 mg, while black tea infused for four minutes has 40 to 100 mg.13

- Finally, the caffeine in leaf powder, such as is found in tea bags, is more readily dissolved in water, and, all other factors being equal, it will have almost twice the caffeine as higher-quality full-leaf tea.14

It is almost impossible to guess or determine how much caffeine is in the coffee we order at restaurants. Few field studies of caffeine content have been made. The following results are adapted from one such study, commissioned by New York City’s WABC-TV Eyewitness News in December 1994, from Associated Analytical Laboratories. Note that a “medium” serving can be more than 13 ounces, and that the caffeine content per serving varies, even among these four samples of coffee, by nearly 100 percent.

Caffeine Content of Coffeehouse Coffees

| Brand, Size | Net Serving Size | Total mg | mg/6oz |

| Dunkin’ Donuts, regular | 12.6 oz | 275 | 147.6 |

| Cooper’s, medium | 9.9 oz | 146 | 99.6 |

| West Side Deli, medium | 13.5 oz | 295 | 103.8 |

| Dalton’s Coffee, regular | 8.9 oz | 148 | 99.7 |

Similar discrepancies have been observed among the decaffeinated coffees served at leading chains across the country. In 1995, Self magazine submitted nine samples of decaffeinated coffee for analysis to Southern Testing & Research Laboratories in North Carolina. Most decaffeinated coffees had less than 10 mg per 6-ounce cup, but Starbucks had more than twice that much. As you review this chart, which also includes data from other similar studies, remember that most cups actually served contain at least 8 ounces of fluid. Results demonstrating such wide variability help to explain how even one cup of coffee sometimes seems to send you up like rocket, while other times a few cups won’t even start your engines.

Caffeine Content in “Decaf”

| Brand | Mg/6-oz serving |

| Starbucks decaffeinated | 25 |

| Dunkin’ Donuts decaffeinated | 10 |

| Au Bon Pain decaffeinated | 7 |

| Starbucks decaffeinated espresso | 6 |

| McDonald’s decaffeinated | 5 |

| 7-Eleven decaffeinated | 4 |

| Tetley decaffeinated tea | 4 |

| Cooper’s decaffeinated | 4 |

| Dalton’s decaffeinated | 2 |

| Sanka | 1.5 |

Myths and misconceptions about caffeine content abound. The amount of caffeine that ends up in your cup of coffee is in part a function of the amount of caffeine contained in the beans you start with. In Appendix B is a list of the caffeine content of various beans as a percentage of total weight.15 In general, the cheaper robusta beans contain almost double the caffeine found in the more expensive arabica beans. Although the two have an otherwise similar compositional profile of such components as minerals, proteins, and carbohydrates, arabica beans also contain significantly more lipids. Tea’s variations in caffeine content depend primarily on the age of the leaves and on how the tea leaves have been cured. The caffeine content by percentage of weight of sen-cha, or green tea, is 2.8 percent; of ma-cha, or green powdered tea, is 4.6 percent; and of ban-cha, or coarse tea, is 2 percent.16 Note that ma-cha, the tea most commonly used in the Japanese tea ceremony, which is green tea made from the smallest leaves of the just budding plant, has the highest concentrations of caffeine by weight of any tea, or of any plant source, for that matter. No caffeine is found in brews from herb and mint teas, as would be expected, since the plants from which they are made do not contain caffeine.

Maté also is an important source of caffeine, but it is even more difficult to estimate how much caffeine is in a cup of maté than it is to do so for a cup of coffee or tea. In addition to Ilex paraguariensis, as many as sixty varieties of plants are used in making the drink. To make matters even more confusing, the caffeine content of maté leaves varies widely according to their age at the time of harvesting. Young maté leaves have at least 2 percent caffeine of their dry weight, while adult leaves, those more than a year old, have about 1.5 percent, and old leaves, those more than two years old, have only about .7 percent.

Guarana is a major source of caffeine for millions of South Americans and is also widely sold in Europe and the United States in herbal elixirs and powders in health food stores. Typical of these products is “Magic Power,” sold in two forms and which has the following ingredients (assuming 5 percent caffeine by weight in seeds as stated in their literature):

- 15 ml alcohol with 5 g guarana seeds, 250 mg caffeine per bottle

- Guarana capsules with 500 mg seeds, 25 mg caffeine per capsule

In Brazil, where guarana carbonated drinks are widely available, some consumers claim the effects are somewhat different from coffee’s, because guarana doesn’t produce jitters. This difference may be their imagination, or it may, as we have seen in other cases of natural drugs, be the result of the chemical complexity of guarana or the fact that it contains other active alkaloids in addition to caffeine.

The amount of caffeine found in chocolate and other cacao products is relatively small. A 1.58-ounce milk chocolate Hershey bar has 12 mg, and an average 6-ounce cup of chocolate prepared from a mix has 5 mg. Appendix B lists the caffeine content of other chocolate products.17

So how much caffeine is in a cup of coffee? Most cups of coffee of about 6 ounces probably contain between 60 and 180 mg of caffeine, which means that 100 mg, the value usually adduced, is as good as any. This is the value repeated throughout this book, and it is meant to be understood in the context of all the reservations and qualifications expressed in this section. The actual content in your cup can range from 40 mg to 400 mg.

Soft Drinks

Soft drinks are a major dietary source of caffeine. The amount in each varies widely. Jolt Cola, at or near the top of any list, has 70 mg in a 12-ounce can, CocaCola has 46 mg, and Canada Dry Diet Cola has 1 mg. Coca-Cola has 7.2 mg more caffeine in a 12-ounce serving than its nearest rival in market share, Pepsi, according to the FDA. The agency says the differences don’t appear to have any health consequences. Even though caffeine is on the FDA’s GRAS list, the list of food additives “generally recognized as safe,” the agency has expressed reservations about excessive caffeine consumption by children and any consumption by pregnant women. But FDA spokesman Jim Greene said in reference to most of the soft drinks ranked, “the effect of the milligram differences among these products is basically nil in the long run.”

Interestingly, 7-Up, one of the best-selling soft drinks in the United States, has made the absence of caffeine the basis for a recent advertising campaign.

Over-the-Counter and Prescription Medications

Caffeine is used as one ingredient in a variety of over-the-counter and prescription compounds. The FDA’s National Center for Drugs and Biologics lists more than one thousand over-the-counter brands with caffeine as an ingredient. These fall into four categories: analgesics, cold remedies, appetite suppressants, and diuretics. Several of the most popular brands are listed in the appendix. In addition, caffeine is the only active ingredient in a number of so-called alertness aids, such as Vivarin, which contains 200 mg per pill, and NoDoz, which contains 100 mg per pill.

Where the Theobromine and Theophylline Are

Each of the methylxanthines considered here—caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline—acts as a physical and mental stimulant, but each has a somewhat different profile of somatic effects. For example, theobromine is a more potent diuretic than either caffeine or theophylline, while theophylline is more suitable for use as a bronchodilator. Cacao is the major source of theobromine, although it contains small amounts of caffeine as well, and its total methylxanthine content will vary with the variety of the plant and the fermentation process. Tea contains a small amount of theophylline in addition to its predominant methylxanthine, caffeine. Maté leaves are a small source of these methylxanthines, though the amounts are so small that some investigators have failed to detect them. The dried leaf has been reported to contain 0.3 percent theobromine and .004 percent theophylline by weight.18 In addition to caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline, there are other, so-called minor, purine alkaloids, which are found in extremely tiny amounts in coffee.

Methylxanthine Content of Cacao Products

| Chocolate Product | Percent Methylxanthine by Weight |

| Sweet chocolate | .36% to .63% theobromine .017% to .125% caffeine |

| Cocoa butter | 1.9% theobromine .21%caffeine |

| Chocolate liquor or baking chocolate | 1.2% theobromine .21% caffeine |

| Milk chocolate | .15% theobromine .02% caffeine |

Methylxanthine Content of Various Botanicals

| Product | Caffeine % | Theophylline % | Theobromine % |

| Coffee | 1.34 | trace | trace |

| Tea | 3.23 | .03 | .17 |

| Cacao | .20 | trace | 1.50 |

| Maté, cola nut, | 2.0 | — | .10 |

| gnarana |

Extracting Caffeine: Industrial Processes and Mr. Wizard’s Laboratory

The United States imports great quantities of caffeine for medical purposes and for spiking soft drinks, most of which is extracted from poor-quality coffee beans or waste tea leaves or collected as a by-product of the decaffeination of coffee and tea. Two techniques are used to produce decaffeinated coffee: bean decaffeination and extract decaffeination. Both are performed on the raw beans to minimize spoilage or loss of aroma.

Bean decaffeination is used when the bean moisture level is less than 40 percent. This process involves static or rotating drums with a water-saturated solvent, such as dichloromethane or supercritical carbon dioxide, selective for caffeine.

Extract decaffeination is used when the bean moisture content is more than 60 percent. In this process, raw coffee beans are usually soaked in nearly boiling water for a few minutes to a few hours, and the resulting liquid is decaffeinated either by liquidliquid extraction with any of the solvents used in the first method or by selective absorprion of caffeine on acid-treated active carbon. Alternative adsorption processes which do not rely on solvents to recover the caffeine from the extract are called “water decaffeination.”19

Extracting caffeine crystals from tea or coffee is a standard first-year organic chemistry experiment. Many people, far removed from academic laboratories, have wondered if there was some easy way to do the same. An amateur chemist provided an approximation of a home extraction process, although with the availability of Vivarin at every corner pharmacy and supermarket, its hard to understand why anyone would risk trying it, something that we, in any case, strongly recommend against:

Mix 180 proof ethanol with very finely ground coffee and mash together. Filter off the solvent. Evaporate the paste and, when dry, dissolve in boiling vodka, until the volume is reduced by about 80 percent. Allow the liquid to sit and cool for two days. If you have done everything right, when you return you should find white caffeine crystals precipitating from the solution.20

Pure caffeine is extremely toxic, and must be handled with hooded ventilation systems, masks, and gloves. Largely for this reason, chemical supply companies are not permitted to sell it to individual purchasers.

Jar containing pure pharmaceutical-grade caffeine, featuring a chilling warning label, which reads in part: “WARNING! MAY BE HARMFUL IF INHALED OR SWALLOWED. HAS CAUSED MUTAGENIC AND REPRODUCTIVE EFFECTS IN LABORATORY ANIMALS. INHALATION CAUSES RAPID HEART RATE, EXCITEMENT, DIZZINESS, PAIN, COLLAPSE, HYPOTENSION, FEVER, SHORTNESS OF BREATH. MAY CAUSE HEADACHE, INSOMNIA, NAUSEA, VOMITING, STOMACH PAIN, COLLAPSE AND CONVULSIONS. MAY CAUSE DIGESTIVE DISTURBANCES, CONSTIPATION, CARDIAC DISORDERS, AND DEPRESSION. MAY CAUSE EPIGASTRIC PAIN, CARDIAC AND RESPIRATORY DISORDERS, AND DEPRESSED MENTAL STATES. EYE CONTACT MAY CAUSE IRRITATION, REDNESS, AND CONJUNCTIVITIS. INGESTION MAY PRODUCE GASTROINTESTINAL IRRITATION, VOMITING, AND CONVULSIONS. FATALITIES HAVE BEEN KNOWN TO OCCUR. Target Organs Affected: Eyes, Skin, Central Nervous System, Repiratory and Gastrointestinal Tract.” (Photograph by Paul Barrow, Biomedical Communications, University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, © 1999 Bennett Alan Weinberg and Bonnie K.Bealer.)