Chapter 4

Interpreting Scriptures

Many people read the Bible generally, and Genesis in particular, as a mythological account of human origins. Others take the Bible’s account quite literally.

Is it possible that Genesis contains a reliable timeline of key events related to the advent of humans? If so, how complete is that information, and how does it compare to today’s scientific observations?

As we have seen in Chapter 1 of this book, Genesis is not intended to be a science text. However, given that it is part of the Torah, and the Torah provides a blueprint for creation, it must represent an accurate description of events and their timing. The entire creation account in Genesis Chapter 1 through Chapter 3 totals a mere 2,000 words or so, while the historical account of early Biblical characters in Chapters 4 through Chapter 11 is but approximately 5,000 words, not much longer than most introductory chapters of books on evolution. Can the Torah then possibly contain a detailed timeline of such rich meaning in so few words? And, where can we find the formula to convert the creation timeline to the time of events as measured by scientists (Human Time)?

Fortunately, the Torah consists of both the Written Law and the Oral Law. The brief account of our origins in the Written Law, as detailed in Genesis, is elaborated on significantly in the Oral Law. This oral tradition, together with related commentaries and mystical works, rivals, even when confined to the creation account only, the combined length of many contemporary biology books.

In fact, the Torah offers in-depth descriptions of what has happened since the beginning of time, specifying when and why it happened; in particular, pertaining to the creation of humans. This constitutes the Genesis timeline for the appearance of humanity and our early history.

The purpose of this chapter is to briefly summarize the method used to extract information from Genesis, to examine the sources that help us do so, and to look at key characters behind some of these sources.

The following is not an exhaustive review of this very complex subject; rather, the material is meant to provide an abbreviated understanding of the sources used throughout the rest of the book to arrive at a comparison of the creation narrative with scientific theory and observation. It also is intended to inspire admiration for the richness of Biblical sources.

This chapter likewise does not describe the Biblical answer regarding a timeline for the appearance and early history of humanity (unlike Chapter 3, which describes the science-based answer). The Biblical answer is developed in later chapters, as required to form a comparison with science’s answer.

The rest of the book includes many references to Biblical topics; these are found primarily in sources described in this chapter.

Genesis as a Valuable Information Source

The Biblical Hebrew language is unlike any other language. While its pictograph letters are not unique, that each letter represents both a letter and a number does set it apart from other human communication systems. The numerical value of a letter, and therefore the word or sentence made from letters, contains meaningful information that has become a focus of study regarding mystical aspects of the oral tradition.

Hebrew is written from right to left. The shape of each letter contains deep significance and meaning while likewise correlating to a major field of study. For example, the first letter in the alphabet, Alef  , has a form that represents the way man was created: “in our image after our likeness.“1 The name for the first man, Adam, is a compound of “a” alef (its first letter), corresponding in Hebrew to “our image,” and dam (the next two letters), corresponding to “after our likeness.” The shape of the letter consists of two small stubs, one on the upper right and one on the lower left, representing heaven and earth (or God and man’s soul), with a diagonal line separating and uniting them simultaneously. This is the secret of the image in which man was created, meaning that he is partly on earth and partly in heaven. This will become much clearer in later chapters when we study humans. Alef numerically represents the number one. One is the only number that counts something (one) from nothing (zero); after that, all counting is something from something. The Alef is thus the beginning of the process in nature—it begins from nothing (i.e., created by God).2 Elaborations on the meaning of the Alef’s shape go on for pages in the literature.

, has a form that represents the way man was created: “in our image after our likeness.“1 The name for the first man, Adam, is a compound of “a” alef (its first letter), corresponding in Hebrew to “our image,” and dam (the next two letters), corresponding to “after our likeness.” The shape of the letter consists of two small stubs, one on the upper right and one on the lower left, representing heaven and earth (or God and man’s soul), with a diagonal line separating and uniting them simultaneously. This is the secret of the image in which man was created, meaning that he is partly on earth and partly in heaven. This will become much clearer in later chapters when we study humans. Alef numerically represents the number one. One is the only number that counts something (one) from nothing (zero); after that, all counting is something from something. The Alef is thus the beginning of the process in nature—it begins from nothing (i.e., created by God).2 Elaborations on the meaning of the Alef’s shape go on for pages in the literature.

Reading Hebrew text is akin to simultaneously reading English (letters and words), reading a scientific formula (e.g., a chemical or physics formula), and reading an abstract diagram explaining various connections and processes. In addition to this richness within the text, there is an oral tradition of divinely revealed text elaboration providing even more detail and helping to guide interpretation as well as connect various sections of the Bible, enabling one to glean even further information.

Needless to say, the process of reading Hebrew text to discern its full meaning requires years of study, an amazing memory and intellect, and teamwork—an effort not unlike developing a scientific theory.

Let us now look at the process and sources used in this book to arrive at

the Human Time events described in Genesis.

How Is Genesis Used to Derive Human Time for Events Measured by Scientists?

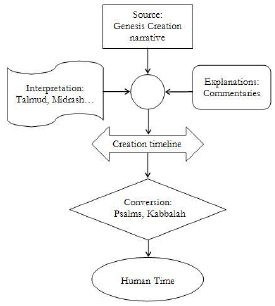

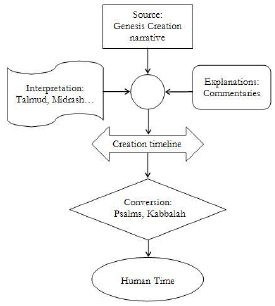

Figure 4.1 illustrates the Biblical sources and how they are used in the book.

Figure 4.1 Biblical Sources

The process used to arrive at Human Time for events in the Genesis narrative is as follows:

1. We begin with the fundamental source—the Genesis creation narrative.

2. We use the oral tradition to interpret Genesis and to obtain a more exact time for each event.

3. We consult key commentaries for clarification and explanations of terms, events, and meaning.

4. Having arrived at an understanding of the events and the time at which they happen (in Creation Time), we convert from Creation Time to Human Time, using the mystical works.

Let us now review the sources and characters in each of these steps. (Genesis, the fundamental source, has been described already; at this point, a review of Annex A containing the Genesis creation text may be helpful.)

Interpretation: The Oral Tradition

Two key components of the Oral Law provide more exact times for each creation event and help us to chronologically organize events: the Talmud and some elements of Midrashim. These sources, along with the rest of the oral tradition, are thought to have been taught to Moses.3 In fact, they are the reason why Moses remained so long on the mountain (as described in the Book of Exodus), as God could have given him the written law in one day. Moses is said to have transmitted this Oral Law to Joshua; Joshua, in turn transmitted it to the 70 Elders; the Elders to the Prophets; and the Prophets to the Great Synagogue.4 It is believed the teachings were later transmitted successively to certain rabbis. Following the destruction of the Second Temple and the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE, it became apparent that the Hebrew community and its learning resources were threatened, and publication was the only way to ensure the Oral Law would be preserved. Thus, around 200 CE, a preserved version of the Oral Law in writing was completed.

The Talmud gets its name from the word Lamud, or “taught,” meaning “the Teaching.” The Mishnah is the foundation and principal part of the Talmud. It was expounded in the academies in Babylon and in Israel during the Middle Ages. In this book, all Talmudic references are from the Babylonian Talmud. As the interpretations increased with the passing of time, the disputations and decisions of the doctors of the law concerning the Mishnah were written down, and these writings constituted another part of the Talmud called the Gemarah. The Mishnah serves first as a kind of redaction of law, and is followed by the Gemarah, serving as an analysis of various opinions leading to definite decisions.

What kind of information does the Talmud reveal about timelines and creation? Below is an excerpt of the detailed timeline for the creation of man revealed for Day 6:

The day consisted of twelve hours. In the first hour, his [Adam’s] dust was gathered; in the second [hour], it was kneaded into a shapeless mass. In the third [hour], his limbs were shaped; in the fourth…5

Midrash means “exposition,” and it denotes the non-legalistic teachings of the Rabbis of the Talmudic era. Midrash6 designates a critical explanation or analysis which, going more deeply than the mere literal sense, attempts to penetrate into the spirit of the scriptures, to examine the text from all sides, and thereby to derive interpretations that are not immediately obvious.

In the centuries following the compilation of the Talmud (about 505 CE), much of this material was compiled into collections known as Midrashim. A prominent example of a Midrash used throughout this book is the Midrash Rabbah, which adds critical details to the Five Books of Moses; another example is Pirkê de Rabbi Eliezer, which includes the impacts on Adam and Eve resulting from their sin.

Table 4.1 provides a summary timeline of events and persons described in this chapter.

| Time Biblical Year |

Time Western calendar |

Event or person |

| 1 |

3760 BCE |

Adam & Eve created |

| 2448 |

1313 BCE |

Torah received by Moses |

| |

lst-2nd century |

Author of Pirkê de Rabbi Eliezer |

| 3979 |

219 CE |

Mishna compiled |

| |

3rd century |

Author of Midrash Rabbah |

| 4128 |

368 CE |

Jerusalem Talmud compiled |

| 4186 |

426 CE |

Babylonian Talmud compiled |

| 4260 |

500 CE |

Babylonian Talmud recorded |

| 4800-4865 |

1040-1105 CE |

Rashi |

| 4954-5030 |

1194-1270 CE |

Ramban |

| |

13th century |

Zohar appears in Spain |

| |

13th-14th centuries |

Isaac ben Samuel of Acre |

| 5294-5332 |

1534-1572 CE |

Arizal |

Table 4.1 Timeline of Biblical Sources and Persons

Midrash Rabbah

Midrash Rabbah7 is dedicated to explaining the Five Books of Moses. Genesis Rabbah is a Midrash to Genesis, assigned by tradition to the renowned Jewish scholar of Palestine, Hoshaiah (circa third century), who commented on the teachings of the Oral Law. The Midrash forms a commentary on the whole of Genesis. The Biblical text is expounded verse for verse, often word for word; only genealogic passages and similar non-narrative information for exposition are omitted.

Midrash Rabbah contains many simple explanations of words and sentences, often in the Aramaic language, suitable for the instruction of youth; it also includes the most varied expositions popular in the public lectures of the synagogues and schools. According to the material or sources at the disposal of the Midrash’s editor, he has strung together various longer or shorter explanations and interpretations of successive passages, sometimes anonymously, sometimes citing the author. He adds to the running commentary connected in some way with the verse in question, or with one of its explanations—a method not unusual in the Talmud and other Midrashim. The chapters of Genesis about the creation of the world and of humans in turn furnish remarkably rich material for this type of commentary. Entire sections are devoted to the discussion of one or two verses of Genesis.

What kind of information does Midrash Rabbah reveal about the early history of humankind? Many kinds, for example, it gives us surprisingly specific information about the Genesis Flood:

The deluge in the time of Noah was by no means the only flood with which this earth was visited. The first flood did its work of destruction as far as Jaffé, and the one of Noah’s days extended to Barbary.8

Barbary refers to the western coastal regions of North Africa, what are now Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya.

Pirkê de Rabbi Eliezer

Pirkê de Rabbi Eliezer (or “Chapters of Rabbi Eliezer”)9 comprises ethical guidelines as well as significant information about Adam and Eve. Many details not found in other sources are revealed in this work.

Despite the book’s bearing an author’s name, the actual writer is unknown. The reputed author is Rabbi Eliezer, who lived in the latter half of the first century CE and in the first decades of the second century. He was famous for outstanding scholarship and is quoted in the Mishnah and Talmud more frequently than any of his contemporaries. Did this owe to the fact that the actual writer of Chapters of Rabbi Eliezer deliberately selected the name of this famous master in Israel as its alleged author? In many respects the book is controversial and unorthodox: controversial in opposing doctrines and traditions current in certain circles of former times; unorthodox in revealing mysteries (including creation mysteries) that were reputed to have been taught in the school of Rabban Jochanan ben Zakkai, the teacher of Rabbi Eliezer.

Who exactly was the teacher of Rabbi Eliezer? Rabban Jochanan ben Zakkai,10 who flourished in the first century CE, helped to preserve and develop Judaism in the years following the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem in 70 CE. He is said to have been smuggled out of the besieged city in a coffin, and to have visited the Roman camp and persuaded the future emperor Vespasian to allow him to set up an academy at Jabneh near the Judean coast. Jochanan established an authoritative rabbinic body there and was revered as a great teacher and scholar. According to the Mishnah,11 traditions were handed down through an unbroken chain of scholars; Jochanan, in receiving the teachings of Hillel and Shammai, formed the last link in that chain. Before his death, Hillel is said to have prophetically designated Jochanan, his youngest pupil, as “the father of wisdom” and “the father of coming generations.”

What did Rabbi Eliezer learn about Adam and Eve? For example, he tells us that as a result of her part in the sin, Eve (and all women) received the following curses: “the afflictions arising from menstruation and the tokens of virginity; the affliction of conception in the womb; and the affliction of child-birth; and death.“12

Explanations—The Commentaries

Commentaries are critical explanations or interpretations of the Biblical texts. The process of arriving at these explanations is rigorous and involves very specific and well-developed rules and methods for the investigation and exact determination of the meaning of the scriptures, both legal and historical.

The interpretation of the Biblical text examines its extended meaning. As a general rule, the extended meaning never contradicts the basic meaning. Commentaries explore four levels of meaning: (1) the plain or contextual meaning of the text, (2) the allegorical or symbolic meaning beyond the literal sense, (3) the metaphorical or comparative meaning as derived from similar occurrences in the text, and (4) the hidden or mystical meaning. There is often considerable overlap, for example when legal understandings of a verse are influenced by mystical interpretations, or when a hint is identified by comparing a word with other instances of the same word.

Two major commentaries used throughout this book are those by Rashi and Ramban. Rashi’s commentary is widely known for presenting the plain meaning of the text in a concise yet lucid fashion. Ramban’s commentary attempts to discover the hidden meanings of scriptural words.

Rashi

Shlomo Yitzhaki (1040–1105 CE), better known by the acronym Rashi13 (RAbbi SHlomo Itzhaki), was a medieval French rabbi famed as being the author of the first comprehensive commentary on the Talmud, as well as for authoring a comprehensive commentary on the Written Law (including Genesis). His is considered the father of all commentaries that followed on the Talmud and the Written Law.

Rashi, acclaimed for his ability to present the basic meaning of the text succinctly, appeals to both learned scholars and beginning students. His works remain a centerpiece of contemporary study. Rashi’s commentary on the Talmud, which covers nearly all of the Babylonian Talmud, has been included in every edition of the Talmud since its first printing in the 1520s. His commentary on the Five Books of Moses is an indispensable aid to students at all levels. The latter commentary alone serves as the basis for more than 300 super-commentaries that analyze Rashi’s choice of language and citations.

Rashi began to write his famous commentary at an early age. Because the Torah was very difficult to properly understand, and the Talmud was even more challenging, Rashi decided to write a commentary in simple language that would allow everyone to more easily learn and understand the Torah. As Rashi was modest, and even after he had become famous far and wide, he hesitated to come out into the open with his commentary. He wanted to first make sure that it would be favorably received. So, he wrote his commentaries on slips of parchment and set out on a two-year journey, visiting the various Torah academies of those days. He traveled incognito, always hiding his identity.

Rashi came to a Torah academy and sat down to listen to the lecture of the attending rabbi. There came a difficult passage that the rabbi struggled to explain to his students. When Rashi was left alone, he took the slip with his commentary, in which that passage was explained simply and clearly, and put it into one of the rabbi’s books. On the following morning when the rabbi opened his book, he found a mysterious slip of parchment in which the passage was so clearly and simply explained that he was amazed. He told his students about it. Rashi listened to their praises of his commentary and saw how useful it was to the students, but he did not say that it was his. And so Rashi went on visiting various academies of the Torah in many cities, and everywhere he planted his slips of commentaries secretly. The way these slips were received made Rashi realize more and more how useful they were, and he continued to write his commentaries. Finally, Rashi was discovered planting his commentary in the usual manner, and the secret was out.

What kind of information on the Creation narrative does Rashi reveal? One example is he teaches that when the Genesis text says, God made man “after our likeness,” it means ‘He made man with the power of understanding and intellect.’14

Ramban

Nachmanides, also known as Rabbi Moses ben Nachman Girondi, Bonastrucça Porta, and by his acronym Ramban15 (Gerona, 1194–Land of Israel, 1270), was a leading medieval scholar, rabbi, philosopher, physician, and Biblical commentator. His commentary on the Five Books of Moses was his last and best known work. He is considered one of the elder sages of mystical Judaism. The Ramban’s commentary on the Torah is believed to be based on careful scholarship and original study of the Bible.

Ramban showed great talent at a very early age. He was a brilliant student, and his scholarship, piety and fine character made him famous far beyond his own community. At the age of 16 he had mastered the whole Talmud with all its commentaries. Nachmanides also studied medicine and philosophy. Not wishing to profit from the Torah, Ramban became a practicing physician in his native town of Gerona, Spain. At the same time he was also the communal Rabbi of Gerona, and later became the Chief Rabbi of the entire province of Catalonia in Spain.

What information pertaining to the story of creation does Ramban reveal? As one example, he teaches that when the Genesis text says, God made man “after our likeness,” it means ‘He made man with moral freedom and free will.’16

Mystical Tradition

Kabbalah is the Jewish mystical tradition that teaches the deepest insights into the essence of God, His interaction with the world, and the purpose of Creation. This tradition provides insight into the nature of the human soul, and in particular, Adam’s soul, and what happened to his soul as a result of the sin, to help us decipher the appearance of humans on earth.

The mystical tradition and its teachings—no less than the Oral Law—are an integral part of the oral tradition. They are traced back to God’s revelation to Moses at Sinai, and some even before (one book is said to have been Adam’s). The Zohar teaches17 that science will inform spirituality, and spirituality will inform science by the time the Messianic era arrives. Kabbalah means ‘reception,’ for we cannot physically perceive the Divine; we merely study the mystical truths.

The primary mystical work is the Zohar.18 The work is a revelation from God communicated through R. Shimon bar Yochai to the latter’s select disciples. Under the form of a commentary on the Five Books of Moses, written partly in Aramaic and partly in Hebrew, it contains a complete theosophy discussing the nature of God, the cosmogony and cosmology of the universe, the soul, sin, redemption, good, evil, and so on.

The Zohar first appeared in Spain in the 13th century and was published by Moses de Leon. De Leon ascribed the work to Shimon bar Yochai, a rabbi of the second century, who, during the Roman persecution, hid in a cave for 13 years studying the Torah and was divinely inspired to write the Zohar.

The father of contemporary Kabbalah is Rabbi Isaac Luria.

Rabbi Isaac Luria

Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534−1572) is commonly known as the Ari, an acronym standing for Elohi Rabbi Isaac, the Godly Rabbi Isaac. No other sage ever had ‘Godly’ as a preface to his name. This was a sign of what his contemporaries thought of him. To this day Rabbi Isaac Luria is referred to as Rabbenu HaAri, HaAri HaKadosh (the holy Ari) or Arizal (the Ari of blessed memory).

At a very early age, Rabbi Isaac Luria lost his father and he went to Cairo, Egypt, where an uncle took care of his upbringing and education. The brilliant youngster’s studies of the Talmud promoted him to the heights of scholarly achievement. Yet Rabbi Isaac Luria’s deep and introspective nature left him unsatisfied by the study of solely traditional sources. He acquired knowledge of Torah and devoted his entire life to its study and dissemination. At an early age he lived by himself for seven years, immersed in the study of the Zohar and other writings.

In his tireless efforts to penetrate the inner chambers of the Torah, he was able to work out an entire system of Kabbalistic doctrine on the world. About the year 1569, he took his family and migrated to Jerusalem, and from there to Safed (in northern Israel), the center of all study of the mystical tradition. Soon, a large group of disciples gathered about him.

Among the most ardent exponents of the Arizal’s teachings was his disciple and successor, Rabbi Chaim Vital. Rabbi Chaim Vital recorded the revelations and explanations of his great master. The Arizal died at the age of 38.19

The Arizal is considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah or Lurianic Kabbalah. His teachings describe new coherent doctrines of the origins of Creation and its cosmic rectification,20 incorporating a recasting and fuller systemization of preceding teachings. In particular, the Arizal’s extensive teachings on the subject of souls are contained in the book Shaar HaGilgulim, composed by Rabbi Chaim Vital and his son Shmuel.21

Time Conversion—Mystical Works

The works described so far (along with a few others) develop an accurate Biblical representation of the appearance of humans in Creation Time. To convert from Creation Time to Human Time, a mystical source is required.

Among the many works, the ones discussed so far are mainstream. To convert timelines, we rely primarily on the eccentric and unconventional work of Isaac ben Samuel of Acre, Otzar HaChaim.

Isaac ben Samuel of Acre

Isaac ben Samuel of Acre22 (fl. 13th–14th centuries) was a Kabbalist who lived in the land of Israel. It is thought Isaac ben Samuel was a pupil of Ramban. Isaac ben Samuel was at Acre when that town was taken by Al-Malik al-Ashraf, and he was thrown into prison with many fellow believers. Escaping the massacre in 1305, he went to Spain. This was the time that Moses de Leon discovered the Zohar.

According to Azulai,23 Isaac ben Samuel of Acre is frequently quoted by prominent Kabbalists (e.g., R. Hayyim Vital; Calabria, 1543–Damascus, 1620). He was an expert in composing the sacred names of God, by the power of which angels were forced to reveal to him the great mysteries. He wrote many works.

Rabbi Isaac ben Samuel developed an original methodology of interpretation, which he designated as the “four ways of NiSAN,” being the acronym of Nistar (hidden), Sod (secret), Emet (truth), and Emet Nekhona (correct truth). The four ways of NiSAN are used by Rabbi Isaac only in his later works, including Otzar HaChaim. This work was translated to English recently by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan, described in his own words as follows:24

There is only one complete copy of this manuscript in the world, and this is in the Guenzberg Collection in the Lenin Library in Moscow…. This is how I got my hands on this very rare and important manuscript…. It took a while to decipher the handwriting, since it is an ancient script.

What did Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan discover when he translated the text? He found a method for converting Creation Time to Human Time. He also found that Rabbi Isaac ben Samuel, in his work Otzar HaChaim, was the first to imply that the universe is billions of years old—at a time when prevalent thought was that the universe was thousands of years in age. Rabbi Isaac ben Samnuel arrived at this conclusion by distinguishing between “solar years” and “divine years,” herein described as Human Time and Divine Time.

Moving through the steps illustrated in Figure 4.1, we discover the timing of Creation events, applying the work of Rabbi Isaac ben Samuel, with some refinements. We can then convert the time of these events to Human Time.

The next chapter develops the time conversion process in detail.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

, has a form that represents the way man was created: “in our image after our likeness.“1 The name for the first man, Adam, is a compound of “a” alef (its first letter), corresponding in Hebrew to “our image,” and dam (the next two letters), corresponding to “after our likeness.” The shape of the letter consists of two small stubs, one on the upper right and one on the lower left, representing heaven and earth (or God and man’s soul), with a diagonal line separating and uniting them simultaneously. This is the secret of the image in which man was created, meaning that he is partly on earth and partly in heaven. This will become much clearer in later chapters when we study humans. Alef numerically represents the number one. One is the only number that counts something (one) from nothing (zero); after that, all counting is something from something. The Alef is thus the beginning of the process in nature—it begins from nothing (i.e., created by God).2 Elaborations on the meaning of the Alef’s shape go on for pages in the literature.

, has a form that represents the way man was created: “in our image after our likeness.“1 The name for the first man, Adam, is a compound of “a” alef (its first letter), corresponding in Hebrew to “our image,” and dam (the next two letters), corresponding to “after our likeness.” The shape of the letter consists of two small stubs, one on the upper right and one on the lower left, representing heaven and earth (or God and man’s soul), with a diagonal line separating and uniting them simultaneously. This is the secret of the image in which man was created, meaning that he is partly on earth and partly in heaven. This will become much clearer in later chapters when we study humans. Alef numerically represents the number one. One is the only number that counts something (one) from nothing (zero); after that, all counting is something from something. The Alef is thus the beginning of the process in nature—it begins from nothing (i.e., created by God).2 Elaborations on the meaning of the Alef’s shape go on for pages in the literature.