6

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar

With Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883–1966), a Maharashtrian Brahmin, the centre of gravity of Hindu nationalism shifts from Punjab and the United Provinces to Maharashtra, where old Congressmen from the Extremist fold, such as B.G. Tilak, had prepared the ground for such an ideology. Savarkar was at first himself an Extremist who did not hesitate to resort to violent methods against the British.1 Arrested in London, where he had taken part in the assassination plot of Curzon-Wyllie, an associate of the Secretary of State, between 1910 and 1937 he spent twenty-seven years in jail, first in the Andamans and then in Ratnagiri (Maharashtra). This is where he wrote Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?, first published anonymously at Nagpur in 1923. This book is the real charter of Hindu nationalism, the ideology which has become precisely equated with the word ‘Hindutva’.

Savarkar wrote this book in prison, after he had come in contact with Khilafatists whose attitude apparently convinced him—a revolutionary till then—that Muslims were the real enemies, not the British.2 Savarkar’s book rests on the assumption that Hindus are weak compared to Muslims. The latter are a closely-knit community that entertain pan-Islamic rather than nationalist sympathies. According to him, they pose a threat to the real nation, namely Hindu Rashtra. Drawing some of his inspiration from Dayananda and his followers, Savarkar defines the nation primarily along ethnic categories. For him, the Hindus descend from the Aryas, who settled in India at the dawn of history and who already formed a nation at that time. However, in Savarkar’s writings, ethnic bonds are not the only criteria of Hindutva. National identity rests for him on three pillars: geographical unity, racial features, and a common culture. Savarkar minimizes the importance of religion in his definition of a Hindu by claiming that Hinduism is only one of the attributes of ‘Hinduness’.3 This stand reflects the fact that, like most ethnoreligious nationalists, Savarkar was not himself a believer.4 Doubtless, Christians and Muslims represented for Savarkar an Otherness of a threatening nature, but, by defining them as part of a race within which they became converts only a few generations earlier, he suggests that they can be reintegrated into Hindu society provided they pay allegiance to Hindu culture. The third criterion of Hindutva—a ‘common culture’—reflects for Savarkar the crucial importance of rituals, social rules, and language in Hinduism. Sanskrit is cited by him as the common reference point for all Indian languages and as ‘language par excellence’.5 Any political programme based on Hindu nationalist ideology has after Savarkar demanded recognition of Sanskrit or Hindi—the vernacular language closest to it—as the national idiom.

There is finally a territorial dimension in this ethnic brand of nationalism. To Savarkar a Hindu is first and foremost someone who lives in the area beyond the Indus river, between the Himalayas and the Indian Ocean, ‘so strongly entrenched that no other country in the world is so perfectly designed by the fingers of nature as a geographical unit’.6 This is why the first Aryans in the Vedic era ‘developed a sense of nationality’. 7 Here a shift to an ethnic rationale is expressed for the enclaved nature of what Savarkar calls ‘Hindustan’, the land of the Hindus,which is described as a decisive factor in the unity of the population on account of intermarriage: ‘All Hindus claim to have in their veins the blood of the mighty race incorporated with and descended from the Vedic fathers.’8 In Savarkar’s mind territory and ethnic unity are inseparable.

Extract from Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?9

What is a Hindu? Although it would be hazardous at the present stage of oriental research to state definitely the period when the foremost

band of the intrepid Aryans made it their home and lighted their first sacrificial fire on the banks of the Sindhu, the Indus,

yet certain it is that long before the ancient Egyptians, and Babylonians had built their magnificent civilization, the holy

waters of the Indus were daily witnessing the lucid and curling columns of the scented sacrificial smokes and the valleys

resounding with the chants of Vedic hymns—the spiritual fervour that animated their souls. The adventurous valour that propelled

their intrepid enterprises, the sublime heights to which their thoughts rose all these had marked them out as a people destined

to lay the foundation of a great and enduring civilization. By the time they had definitely cut themselves aloof from their

cognate and neigh-bouring people especially the Persians, the Aryans had spread out to the farthest of the seven rivers, Sapta

Sindhus, and not only had they developed a sense of nationality but had already succeeded in giving it ‘a local habitation

and a name!’ Out of their gratitude to the genial and perennial network of waterways that ran through the land like a system

of nerve-threads and wove them into a Being, they very naturally took to themselves the name of Sapta Sindhus an epithet that

was applied to the whole of Vedic India in the oldest records of the world, the Rigveda itself. About Aryans, or the cultivators, as they essentially were, we can well understand the divine love and homage they

bore to these seven rivers presided over by the River, ‘the Sindhu’, which to them were but a visible symbol of the common

nationality and culture.

The Indians in their forward march had to meet many a river as genial and as fertilizing as these but never could they forget the attachment they felt and the homage they paid to the Sapta Sindhus which had welded them into a nation and furnished the name which enabled their forefathers to voice forth their sense of national and cultural unity. Down to this day a Sindhu—a Hindu—wherever he may happen to be, will gratefully remember and symbolically invoke the presence of these rivers that they may refresh and purify his soul.

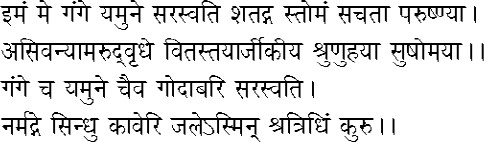

Not only had these people been known to themselves as ‘Sindhus’ but we have definite records to show that they were known to their surrounding nations—at any rate to one of them—by that very name, ‘Sapta Sindhu’. The letter ‘s’ in Sanskrit is at times changed into ‘h’ in some of the Prakrit languages, both Indian and non-Indian. For example, the word Sapta has become Hapta not only in Indian Prakrits but also in the European languages too; we have Hapta i.e., week, in India and ‘Heptarchy’ in Europe, Kesari in Sanskrit becomes Kehari in old Hindi, Saraswati becomes Harhvati in Persian and Asur becomes Ahur. And then we actually find that the Vedic name of our nation Sapta Sindhu had been mentioned as Hapta Hindu in the Avesta by the ancient Persian people. Thus in the very dawn of history we find ourselves belonging to the nation of the Sindhus or Hindus and this fact was well known to our learned men even in the Puranic period. In expounding the doctrine that many of the Mlechha tongues had been but the mere offshoots of the Sanskrit language the Bhavishya Puran clearly cites this fact and says—

Thus knowing for certain that the Persians used to designate the Vedic Aryans as Hindus and knowing also the fact that we generally call a foreign and unknown people by the term by which they are known to those through whom we come to know them, we can safely conclude that most of the remoter nations that flourished then must have applied the same epithet ‘Hindu’ to our land and people as the ancient Persians did. Not only that but even in the very region of the Sapta Sindhus the thinly scattered native tribes too, must have been knowing the Aryans as Hindus in the local dialects in accordance with the same linguistic law. Further on, as the Vedic Sanskrit began to give birth to the Indian Prakrits which became the spoken tongues of the majority of the descendants of these very Sindhus as well as the assimilated and the crossborn castes, these too might have called themselves as Hindus without any influence from the foreign people. For the Sanskrit S changes into H as often in Indian Prakrits as in the non-Indian ones. Therefore, so far as definite records are concerned, it is indisputably clear that the first and almost the cradle name chosen by the patriarchs of our race to designate our nation and our people, is Sapta Sindhu or Hapta Hindu and that almost all nations of the then known world seemed to have known us by this very epithet, Sindhus or Hindus.

Name Older Still: So far we have been treading on solid ground of recorded facts, but now we cannot refrain ourselves from making an occasional excursion into the borderland of conjecture. So far we have not pinned our faith to any theory about the original home of the Aryans. But if the most widely accepted theory of their entrance into India be relied on, then a natural curiosity arises as to the origin of the names by which they called the new scenes of their adopted home. Did they coin all those names from their own tongue? Could they have done so? Is it not generally true that when we meet a new scene or enter a new country we call them by the very names—maybe in a slightly changed form so as to suit our vocal ability or taste—by which they are known to the native people there? Of course, at times we love to call new scenes by names redolent with the memory of the clear old ones—especially when new colonies are being established in a virgin and thinly populated continent. But this explanation could only be satisfactory when it is proved that the name given to the new place already existed in the old country and even then it could not be denied that the other process of calling new scenes by the names which they already bear is more universally followed. Now we know it for certain that the region of the Sapta Sindhus was, though very thinly, populated by scattered tribes. Some of them seem to have been friendly towards the newcomers and it is almost certain that many an individual had served the Aryans as guides and introduced them to the names and nature of the new scenes to which the Aryans could not be but local strangers. The Vidyadharas, Apsaras, Yakshas, Rakshasas, Gandharvas and Kinnaras were not all or altogether inimical to the Aryans as at times they are mentioned as being benevolent and good-natured folks. Thus it is probable that many names given to these great rivers by the original inhabitants of the soil may have been sanskritised and adopted by the Aryans. We have numerous proofs of this nature in the assimilative expansion of those people and their tongues; witness the words Shalankantakata, Malaya, Milind, Alasada (Alexandria), Suluva (Selucus), etc. If this be true then it is quite probable that the great Indus was known as Hindu to the original inhabitants of our land and owing to vocal peculiarity of the Aryans it got changed into Sindhu when they adopted it by the operation of the same rule that S is the sanskritised equivalent of H. Thus Hindu would be the name that this land and the people that inhabited it bore from time so immemorial that even the Vedic name Sindhu is but a later and secondary form of it. If the epithet Sindhu dates its antiquity in the glimmering twilight of history then the word Hindu dates its antiquity from a period so remoter than the first that even mythology fails to penetrate—to trace it to its source.

Hindus, a Nation: The activities of so intrepid a people as the Sindhus or Hindus could no longer be kept cooped or cabined within the narrow compass of the Panchanad or the Punjab. The vast and fertile plains farther off stood out inviting the efforts of some strong and vigorous race. Tribe after tribe of the Hindus issued forth from the land of their nursery and, led by the consciousness of a great mission and their Sacrificial Fire that was the symbol thereof, they soon reclaimed the vast, waste and very-thinly populated lands. Forests were felled, agriculture flourished, cities rose, kingdoms thrived—the touch of the human hand changed the hole face of the wild and unkempt nature. But while these great deeds were being achieved the Aryans had developed to suit their individualistic tendencies and the demandsof their new environments a policy that was but loosely centralised. As time passed on, the distances of their new colonies increased, and different peoples of other highly developed types began to be incorporated into their culture, the different settlements began to lead life politically very much centred in themselves. The new attachments thus formed, though they could not efface the old ones, grew more and more pro-nounced and powerful until the ancient generalizations and names gave way to the new. Some called themselves Kurus, others Kashis or Videhas or Magadhas while the old generic name of the Sindhus or Hindus was first overshadowed and then almost forgotten. Not that the conception of a national and cultural unity vanished, but it assumed other names and other forms, the politically most important of them being the institution of a Chakravartin. At least the great mission which the Sindhus had undertaken of founding a nation and a country, found and reached its geographical limit when the valorous Prince of Ayodhya made a triumphant entry in Ceylon and actually brought the whole land from the Himalayas to the Seas under one sovereign sway. The day when the Horse of Viceroy returned to Ayodhya unchallenged and unchallengeable, the great white Umbrella of Sovereignty was unfurled over that Imperial throne of Ramachandra, the brave, Rama-chandra the good, and a loving allegiance to him was sworn, not only by the Princes of Aryan blood but Hanuman, Sugriva, Bibhishana from the south—that day was the real birthday of our Hindu people. It was truly our national day; for Aryans and Anaryans knitting themselves into a people were born as a nation. It summed up and politically crowned the efforts of all the generations that preceded it and it handed down a new and common mission, a common banner, a common cause which all the generations after it had consciously or unconsciously fought and died to defend.

Foreign Invaders: But as it often happens in history this very undisturbed enjoyment of peace and plenty lulled our Sindhusthan, in a sense of false security and bred a habit of living in the land of dreams. At last she was rudely awakened on the day when Mohammad of Gazni crossed the Indus, the frontier line of Sindhusthan and invaded her. That day the conflict of life and death began. Nothing makes Self conscious of itself so much as a conflict with non-self. Nothing can weld peoples into a nation and nations into a state as the pressure ofa common foe. Hatred separates as well as unites. Never had Sindhus-than a better chance and a more powerful stimulus to be herself forged into an indivisible whole as on that dire day, when the great iconoclast crossed the Indus. The Mohammedans had crossed that stream even under Kasim, but it was a wound only skin-deep, for the heart of our people was not hurt and was not even aimed at. The contest began in grim earnestness with Mohammad and ended, shall we say, with Abdalli? From year to year, decade to decade, century to century, the contest continued. Arabia ceased to be what Arabia was; Iran annihilated; Egypt, Syria, Afghanistan, Baluchistan, Tartary—from Granada to Gazni—nations and civilizations fell in heaps before the sword of Islam of Peace!! But here for the first time the sword succeeded in striking but not in killing. It grew blunter each time it struck, each time it cut deep but as it was lifted up to strike again the wound stood healed. Vitality of the victim proved stronger than the vitality of the victor. The contrast was not only grim but it was monstrously unequal. It was not a race, a nation of a people India had to struggle with. It was nearly all Asia, quickly to be followed by nearly all Europe. The Arabs had entered Sindh and single-handed they could do little else. They soon failed to defend their own independence in their homeland and as a people we hear nothing further about them. But here India alone had to face Arabs, Persians, Pathans, Baluchis, Tartars, Turks, Moguls—a veritable human Sahara whirling and columning up bodily in a furious world storm! Religion is a mighty motive force. So is rapine. But where religion is goaded on by rapine and rapine serves as a handmaiden to religion, the propelling force that is generated by these together is only equalled by the profundity of human misery and devastation they leave behind them in their march. Heaven and hell making a common cause—such were the forces, overwhelmingly furious, that took India by surprise the day Mohammad crossed the Indus and invaded her. Day after day, decade after decade, century after century, the ghastly conflict continued and India single-handed kept up the flight morally and militarily. The moral victory was won when Akbar came to the throne and Darashukoh was born. The frantic efforts of Aurangzeb to retrieve their fortunes lost in the moral field only hastened the loss of the military fortunes on the battlefield as well. At last Bhau, as if symbolically, hammered the ceiling of the Imperial Seat of theMoghals to pieces. The day of Panipat rose, the Hindus lost the battle, but won the war. Never again had an Afghan dared to penetrate to Delhi, while the triumphant Hindu banner that our Marathas had carried to Attock was taken up by our Sikhs and carried across the Indus to the banks of the Kabul.

Hindutva at Work: In this prolonged furious conflict our people became intensely conscious of ourselves as Hindus and were welded into a nation to an extent unknown in our history. It must not be forgotten that we have all along referred to the progress of the Hindu movement as a whole and not to that of any particular creed or religious section thereof—of Hindutva and not Hinduism only. Sanatanists, Satnamis, Sikhs, Aryas, Anaryas, Marathas and Madrasis, Brahmins and Panchamas—all suffered as Hindus and triumphed as Hindus. Both friends and foes contributed equally to enable the words Hindu and Hindusthan to supersede all other designations of our land and our people. Aryavartha and Daxinapatha, Jambudweep and Bharatvarsha, none could give so eloquent an expression to the main political and cultural point at issue as the word Hindusthan could do. All those on this side of the Indus who claimed the land from Sindhu to Sindhu, from the Indus to the seas, as the land of their birth, felt that they were directly mentioned by that one single expression, Hindusthan. The enemies hated us as Hindus and the whole family of peoples and races, of sects and creeds that flourished from Attock to Cuttack was suddenly individualised into a single Being. We cannot help dropping the remark that no one has up to this time taken the whole field of Hindu activities from AD 1300 to 1800 into survey from this point of view, mastering the details of the various now parallel, now correlated movements from Kashmir to Ceylon and from Sindh to Bengal and yet rising higher above them all to visualise the whole scene in its proportion as an integral whole. For it was the one great issue to defend the honour and independence of Hindusthan and maintain the cultural unity and civic life of Hindutva and not Hinduism alone, but Hindutva, i.e. Hindudharma that was being fought out on the hundred fields of battle as well as on the floor of the chambers of diplomacy. This one word, Hindutva, ran like a vital spinal cord through our whole body politic and made the Nayars of Malabar weep over the sufferings of the Brahmins of Kashmir. Our bards bewailed the fall of Hindus, our seersroused the feelings of Hindus, our heroes fought the battles of Hindus, our saints blessed the efforts of Hindus, our statesmen moulded the fate of Hindus, our mothers wept over the wounds and gloried over the triumphs of Hindus . . . no people in the world can more justly claim to get recognized as a racial unit than the Hindus and perhaps the Jews. A Hindu marrying a Hindu may lose his caste but not his Hindutva. A Hindu believing in any theoretical or philosophical or social system, orthodox or heterodox, provided it is unquestionably indigenous and founded by a Hindu may lose his sect but not his Hindutva—his Hinduness—because the most important essential which determines it is the inheritance of the Hindu blood. Therefore all those who love the land that stretches from Sindhu to Sindhu from the Indus to the Seas, as their fatherland consequently claim to inherit the blood of the race that has evolved, by incorporation and adaptation, from the ancient Suptasindhus can be said to possess two of the most essential requisites of Hindutva.

Common Culture: But only two; because a moment’s consideration would show that these two qualifications of one nation and one race—of a common fatherland and therefore of a common blood—cannot exhaust all the requisites of Hindutva. The majority of the Indian Mohammedans may, if free from the prejudices born of ignorance, come to love our land as their fatherland, as the patriotic and noble-minded amongst them have always been doing. The story of their conversions, forcible in millions of cases, is too recent to make them forget, even if they like to do so, that they inherit Hindu blood in their veins. But can we, who here are concerned with investigating into facts as they are and not as they should be, recognize these Mohammedans as Hindus? Many a Mohammedan community in Kashmir and other parts of India as well as the Christians in South India observe our caste rules to such an extent as to marry generally within the pale of their castes alone; yet, it is clear that though their original Hindu blood is thus almost unaffected by an alien adulteration, yet they cannot be called Hindus in the sense in which that term is actually understood, because, we Hindus are bound together not only by the tie of the love we bear to a common fatherland and by the common blood that courses through our veins and keeps our hearts throbbing and our affections warm, but also by the tie of the common homage we pay to our great civilization—our Hindu culture, which could not be better rendered than by the word Sanskrit suggestive as it is of that language, Sanskrit, which has been the chosen means of expression and preservation of that culture, of all that was best and worth preserving in the history of our race. We are one because we are a nation, a race and own a common Sanskriti (civilization) in the case of some of our Mohammedan or Christian countrymen who had originally been forcibly converted to a non-Hindu religion and who consequently have inherited along with Hindus, a common Fatherland and a greater part of the wealth of a common culture—language, law, customs, folklore and history—are not and cannot be recognized as Hindus. For though Hindusthan to them is Fatherland as to any other Hindu yet it is not to them a Holyland too. Their Holyland is far off in Arabia or Palestine. Their mythology and Godmen, ideas and heroes are not the children of this soil. Consequently their names and their outlook smack of a foreign origin. Their love is divided. Nay, if some of them be really believing what they profess to do, then there can be no choice—they must, to a man, set their Holyland above their Fatherland in their love and allegiance. That is but natural. We are not condemning nor are we lamenting. We are simply telling facts as they stand. We have tried to determine the essentials of Hindutva and in doing so we have discovered that the Bohras and such other Mohammedan or Christian communities possess all the essential qualifications of Hindutva but one, and that is that they do not look upon India as their Holyland.

It is not a question of embracing any doctrine propounding any new theory of the interpretation of God, Soul and Man, for we honestly believe that the Hindu Thought—we are not speaking of any religion which is dogma—has exhausted the very possibilities of human speculation as to the nature of the Unknown—if not the Unknowable, or the nature of the relation between that and thou. Are you a monist—a monotheist—a pantheist—an atheist—an agnostic? Here is ample room, O soul! Whatever thou art, to love and grow to thy fullest height and satisfaction in this Temple of temples, that stands on no personal foundation of Truth. ‘Why goest then to fill thy little pitcher to wells far off, when thou standest on the banks of the crystal-streamed Ganges herself? Does not the blood in your veins, O brother of our common forefathers, cry aloud with the recollections of the dear oldscenes and ties from which they were so cruelly snatched away at the point of the sword? Then come ye back to the fold of your brothers and sisters who with arms extended are standing at the open gate to welcome you—their long lost kith and kin. Where can you find more freedom of worship than in this land where a Charvak could preach atheism from the steps of the temple of Mahakal—more freedom of social organisation than in the Hindu society where from the Patnas of Orissa to the Pandits of Benares, from the Santalas to the Sadhus, each can develop a distinct social type of polity or organize a new one? Verily, whatever could be found in the world is found here too. And if anything is not found here it could be found nowhere. Ye, who by race, by blood, by culture, by nationality possess almost all the essentials of Hindutva and had been forcibly snatched out of our ancestral home by the hand of violence—ye, have only to render wholehearted love to our common Mother and recognize her not only as Fatherland (Pitribhu) but even as a Holyland (Punyabhu); and ye would be most welcome to the Hindu fold.

This is a choice which our countrymen and our old kith and kin, the Bohras, Khojas, Memons and other Mohammedan and Christian communities are free to make—a choice again which must be a choice of love. But as long as they are not minded thus, so long they cannot be recognized as Hindus.

1 See V.S. Anand, Savarkar—A Study in the Evolution of Indian Nationalism (London: Woolf, 1967); H. Srivasthava, Five Stormy Years: Savarkar in London (New Delhi: Allied Publishers, 1983); Chitragupta, Life of Barrister Savarkar (Bombay: Acharya Balarao Savarkar, 1987). On the revolutionary movement in Maharashtra, see H.M. Ghodke, Revolutionary Nationalism in Western India (New Delhi: Classical Publishing Company, 1990).

2 D. Keer, Veer Savarkar (Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1988), p. 161.

3 According to Savarkar, ‘a man can be as truly a Hindu as any without believing in the Vedas as an independent religious authority’. Hindutva, p. 81.

4 D. Keer, Veer Savarkar, p. 201. On that point, see the typology developed by Ashis Nandy, ‘An Anti-Secularist Manifesto’, Seminar, October 1985, p. 15.

5 Hindutva, p. 95.

6 Ibid., p. 82.

7 Ibid., p. 5.

8 Ibid., p. 85.

9 V.D. Savarkar, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu? (1923; rpnt. New Delhi: Bharatiya Sahitya Sadan, 1989), pp. 4–12, 42–6, 90–2, 113–15.