This essay constitutes a flashback in two senses. The minor sense: I wrote a chapter on The Chase in a little book on Arthur Penn published about fifteen years ago, in the days of my critical innocence (or culpable ignorance, as you will)—innocence, above all, of concepts of ideology, and of any clearly defined political position. The major sense: the film was released some years before the period with which this book is concerned. My evaluation of The Chase has not changed, but my sense of the kind of importance to be attributed to it has changed somewhat: I now see it as a seminal work, anticipating many of the major developments that took place in the Hollywood cinema during the decade following its production, hence a fitting starting point for this investigation. The present account will differ from the earlier, not only in approach but in ambition. There the aim (within the framework of an uncomplicatedly auteurist study) was to provide an appreciation of The Chase as “an Arthur Penn film,” despite the obviously collaborative nature of the project and despite its auteur’s own explicit reservations, marking a phase in a personal development. Here, while reaffirming my admiration for the film (and for Penn’s work in general—Night Moves is among the finest Hollywood films of the 70s), I use it partly as a pretext for a number of more widespread concerns that are basic to this book: to establish a far more complex attitude toward the auteur theory; to introduce certain critical/theoretical concepts fundamental to my present position, which will reflect in particular on assumptions about “realism” and the “realistic”; to initiate a discussion of the differences (specifically, the ideological differences, though of course all differences are in a looser sense ideological) between the Classical and modern Hollywood cinema (one can take 1960 as a convenient, though to some degree arbitrary, point of demarcation).

We may begin with Penn’s own attitude to the film and with the bourgeois myth of “the artist” that would have us attach a definitive importance to it: the myth of the artist as a superior being, donating to the world works which are the result of his conscious intentions and over which (at least if they are successful) he is assumed to have control. It may appear superfluous, after two decades of structuralism, semiotics, and psychoanalysis, to attack the “intentionalist fallacy” yet again; but it dies hard, as anyone involved in film education will be aware. If the director says his film is bad, how can the critic assert that it is good? If the director claims total unawareness of certain layers of meaning in his work, then how can those layers of meaning exist outside the critic’s imagination? If the director (“the artist”) says he had no control over a given film, then how can that film be worth defending? One of the major concerns of twentieth-century aesthetics has been progressively to answer, and in effect dismiss, such questions: first, through the “primitive” use of psychoanalysis (the artist is not aware of his own unconscious impulses), a use that proved perfectly compatible with, and assimilable into, traditional aesthetics; then, through Marxist concepts of ideology (where traditional and modern aesthetics part company), revealing a whole range of cultural assumptions, tensions, and contradictions operating through codes, conventions, and genres, largely beyond the artist’s control; finally, through the sophisticated use of psychoanalytical theory that seeks to explain, not merely the individual “case,” but ideology itself, the construction of the subject within it, the relationship between subject and spectacle.

Yet an important sense remains in which the production of a work is an intentional act—(the intentions of several or many may of course be involved)—and the discernible presence of authorial “fingerprints,” “signature,” “touch,” etc., remains one of the clearest tokens of the specificity of a particular text. The error of primitive auteurism lay in its reduction of the potential interest of a film to its authorial signature, so that a film was worth examination only in so far as it could be shown to be characteristic (stylistically, thematically) of Ray, Mann, or Hawks, for instance: the rest was “interference,” “an intractable scenario,” attributable to the imposition of unsuitable projects or the misguided commercialism of producers. In discussing Hollywood movies now, I prefer to speak of the “intervention” of a director in a given project (even if the project was of his choice, even if he also wrote the screenplay), seeing him as more catalyst than creator. There is a level on which The Chase is palpably “an Arthur Penn film”: the level of performance. The core of Penn’s work, the source of its energy, has always been his work with actors, and the surface aliveness of the film, and much of its emotional intensity and complexity, derives from the responsiveness to his intervention of a magnificent cast.1 I acknowledge this at the outset because it is not a level with which the present discussion will be explicitly concerned, yet it must certainly affect any reading of the film in ways that may be too oblique to be precisely defined. Suffice it to say that if The Chase had been directed by a Michael Winner or a J. Lee Thompson, it is probable that, however resonant the project, it would never have caught my attention.

As for Penn’s partial rejection of The Chase, the critic’s perspective on a film is likely to be very different from the filmmaker’s. Penn worked on the elaboration of the scenario in close collaboration, first with Lillian Hellman, then with Horton Foote; he established and retained a marvelous rapport with the actors. What made the experience of the film unpleasant to the extent that he is still almost traumatized by the memory of it is the fact that he was denied the right to edit. He attaches a definitive importance to editing—the process of “extracting” the film from the “raw material.” From his viewpoint, to deny him the right to edit is effectively to destroy the film, to make it no longer truly his: it becomes, in his own words, “a film that I cannot embrace.” He has two specific complaints: To begin with, in the first takes the actors followed the script; then, getting into their roles, they became freer and more spontaneous and (especially in the case of Marlon Brando) began to improvise, so that later takes were far more developed, Brando in particular giving an apparently extraordinary performance. The editor (acting presumably on instructions from Sam Spiegel, the producer) in most cases returned to the script and the earlier takes, jettisoning the rest (though some of Brando’s impromptus remain in the final cut). Second, the intended effect of the ending was destroyed by the editor’s reversal of the last two scenes: the scene in which Anna (Jane Fonda), waiting outside the hospital, is told of her lover’s death was meant to precede the scene in which Calder (Brando) and his wife Ruby (Angie Dickinson) drive away.

I shall return later to the question of the ending. As for the first complaint, The Chase as we have it is above all an ensemble film; if Brando’s role stands out from the rest, it is because of the character’s position within the diegesis (his authority and his isolation as sheriff). Brando’s performance in the discarded takes was doubtless remarkable, but Brando’s performances tend often to be so remarkable that they seriously unbalance the film. This happens, in my opinion, in Last Tango in Paris and in Penn’s own The Missouri Breaks; though Penn disagrees, I think it might have happened in The Chase. More generally, Penn complains that the editor chose inferior takes throughout: “It is not the verbal content of the improvisations that I so sorely miss but the quality of performance that was present in the more loosely performed ‘improvised’ takes. The failure in the editor’s choices is not with his adherence to the text—written by at least three and perhaps four people—it is with his blind and heavy choice of the most conventional take against those which are eccentric, antic and unorthodox.” As the material Penn shot is inaccessible (and perhaps no longer in existence) I cannot comment on this, beyond saying that the film as we have it demonstrates effectively that Penn’s worst, “most conventional” takes are ten times as exciting as most directors’ best.

One should also take into account Penn’s attitude to Hollywood. A New York intellectual with one eye on Europe, he shows little positive interest in the Hollywood genres for their own sake: they are at best vehicles for making “significant statements,” at worst obstructions to be attacked and destroyed. He shows little sense that the genres—western, melodrama, horror film—are inherently rich in potential meaning. His remark that The Chase is “a Hollywood film, not a Penn film” was obviously intended to be derogatory. I think it says far more than he intended—that the layers of meaning of which Penn appears to be unaware in the film are intricately bound up with, determined by, its place in the evolution of genres and the ideological shifts that evolution enacts. It is as a Hollywood film that I shall discuss The Chase here.

In order to gain the kind of perspective on films that is impossible (or at least highly improbable) for their makers, I want to introduce concepts drawn from the work of two diverse but variously influential aestheticians.

In Art and Illusion E. H. Gombrich offers one of the classic statements about representation—about the relationship between reality and art. He quotes, with qualified approval, Zola’s definition of a work of art as “a corner of nature seen through a temperament,” and goes on to “probe it further.” It is insufficient to treat representation as reality mediated simply by the individual artist: many other factors contribute to the mediation. Basic is the choice of tools and materials. Two landscape artists, trying faithfully to reproduce the same scene, one using a hard pencil, one working in oils, will offer two very different versions of the reality in front of them; their different media will influence them to see it differently, the former seeing everything in terms of line and shape, the latter in terms of mass and color. It is easy to extend this to the cinema and its available technology. The reality the screen so seductively offers is at all points mediated by the choice of camera, lens and focus; the argument can be developed to include editing and camera movement. Nor is this simply a matter of availability: also important are the conventions dominant within a given period. Even at the level of technology and shooting/editing method, The Deer Hunter cannot be My Darling Clementine; try to make a classical Hollywood film in black and white in the 70s and the overall impression will be affectation (The Last Picture Show).

But what most concerns me here, for its bearing on Hollywood genres, character types, and narrative conventions, is Gombrich’s perception of the extent to which art is dependent upon the availability of “schemata” (established patterns, formulas, stereotypes), and the degree to which the nature of the particular work is determined by the particular schemata at the artist’s disposal. Gombrich offers numerous examples from art history, from which I shall select two:

Perhaps the earliest instance of this kind dates back more than three thousand years, to the beginnings of the New Kingdom in Egypt, when the Pharaoh Thutmose included in his picture chronicle of the Syrian campaign a record of plants he had brought back to Egypt. The inscription, though somewhat mutilated, tells us that Pharaoh pronounces these pictures to be “the truth.” Yet botanists have found it hard to agree on what plants may have been meant by these renderings. The schematic shapes are not sufficiently differentiated to allow secure identification. (p. 67)

The implication is that the illustrations, while intentionally drawn from life, were heavily influenced by the schemata of plant drawings available.

When Dürer published his famous woodcut of a rhinoceros, he had to rely on second-hand evidence which he filled in from his own imagination, colored, no doubt, by what he had learned of the most famous of exotic beasts, the dragon with its armoured body. Yet it has been shown that this half-invented creature served as a model for all renderings of the rhinoceros, even in natural history books, up to the eighteenth century. (pp. 70–71)

Gombrich goes on to quote James Bruce’s claim that his 1789 illustration of a rhinoceros, “designed from the life,” contrasts with Dürer’s (“wonderfully ill-executed in all its parts”), and to show that Bruce’s picture still, nonetheless, derives from the Dürer tradition rather than from “nature.” Gombrich concludes that “the familiar will always remain the starting-point for the rendering of the unfamiliar…. Without some starting-point, some initial schema, we could never get hold of the flux of experience. Without categories, we could not sort out our impressions” (p. 76).

The usefulness of this—suitably modified and extended to encompass movement and narrative, the term “schemata” covering characters and narrative patterns with terms such as “genres” and “cycles” substituted for Gombrich’s “categories”—in exploring a traditional art like the Hollywood cinema should be clear. Crucially, it offers an invaluable corrective to all those naive notions of “the realistic” (whether merely descriptive or, as is almost invariably the case, evaluative) that still obstinately linger on. Whenever filmmakers or critics lay claim to a new realism, we would do well to remember Mr. Bruce’s rhinoceros, adopt a certain skepticism, and examine the work in question in relation to the available schemata. An acquaintance (not a casual moviegoer, but a person in a position of responsibility in film culture) once informed me confidently that Mandingo must be a bad film because it showed a southern plantation and mansion in a state of decay, and “in reality” they were extremely well maintained. Leaving aside the assumption of an absoluteness that allows for no exceptions (all southern mansions?), such a comment naively confuses the highly conventionalized genre of melodrama (only in relation to which can the film be properly understood) with some vague notion of documentary reconstruction, assuming, with equal naiveté, the superiority of the latter mode. The decaying mansion of Mandingo relates to one of the most important and enduring schemata of American culture, the “terrible house,” whose line of descent can be traced from Poe (The Fall of the House of Usher) to Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre). (For a more comprehensive treatment, see Andrew Britton’s analysis of Mandingo in Movie 22.) The TV movie The Day After represents an immediately topical instance of this misconception at time of writing. It has been widely advertised, and generally received, as offering a “realistic” depiction of the aftermath of nuclear war. It may be accurate enough (though surely reprehensibly understated) in the information it offers as to the physical effects of nuclear attack; as a narrative, however, it relies extensively on the disaster movies of the 70s, both in overall structure and in specific, detailed narrative strategies. Critics who have noticed this see it as invalidating the film, in my opinion quite unjustifiably: “the familiar will always remain the starting point for the rendering of the unfamiliar.” The Chase itself was savagely mauled by the majority of critics on its release because of its alleged exaggerations: “Texas isn’t really like that”—a perception as misguided as it is irrelevant.

I shall at this point list some of the traditional schemata that structure The Chase, using as a convenient touchstone Ford’s Young Mr. Lincoln—convenient because it is likely to be familiar to readers, because it shares so many of the later film’s schemata, and because there is obviously no question of any direct link between the two films, the notion of schemata going far beyond any question of influence.

1. “The Law,” embodied in a male authority figure, the superior, charismatic individual (Lincoln; Sheriff Calder).

2. Woman as the hero’s support and inspiration (Ann Rutledge; Ruby).

3. The innocent young, accused of murder, in need of the authority figure’s protection and defense (the Clay brothers; Bubber Reeves).

4. The lynch mob—townspeople, normally “respectable citizens”—who attempt to break into the jail.

5. The mother of the accused (Mrs. Clay; Mrs. Reeves) and her anxiety for the safety of her son(s).

6. The young wife of the accused (Hannah; Anna), also concerned for his safety.

7. Religion (Lincoln’s appeal to the bible in the lynching scene; Miss Henderson and her reiterated “I’m praying for you”).

8. Phallic imagery linking violence with sexuality (the lynch party’s battering ram; the repeated, explicit play on the connotations of pistols—“With all those pistols you’ve got there, Emily, I don’t think there’d be room for mine”).

9. Books and learning as emblems of progress (Lincoln’s Blackstone; the university model presented to Val Rogers on his birthday).

10. The emblem of a lost happiness/innocence (the memory of Ann Rutledge; The Chase’s ruined building. As the parallel here is somewhat weak and inexact, I shall adduce two examples from outside Young Mr. Lincoln: the “Rosebud” of Citizen Kane and “the river” of Written on the Wind).

It becomes clear at this point that Gombrich is not enough. Before examining in detail the implications of the recurrence of these schemata over a quarter of a century (they can be traced back, of course, to earlier times and forward to the present), we must pass beyond him, exposing his limitations. They could perhaps be said to expose themselves, in the passage following directly on from the last sentence I quoted: “Without categories, we could not sort out our impressions. Paradoxically, it has turned out that it matters relatively little what these first categories are.”

If the absence here of any political dimension, of any concept of ideology and of schemata as its concrete embodiment, is not immediately obvious, this is because Gombrich restricts his examples entirely to flora and fauna; had he included examples from representations of the human form (the nude, for instance), the absence could not have been so easily covered by the assumption of neutrality. For Gombrich, apparently, the schemata are without important inherent meaning, abstract counters the artist can use as he pleases. The untenability of such a position becomes even more obvious when one applies it to the larger narrative forms such as the novel and the cinema. Gombrich’s tendency, in fact, is generally to depoliticize art and aesthetics. He ends the chapter I have been drawing upon (“Truth and the Stereotype”) by remarking that “the form of a representation cannot be divorced from its purpose and the requirements of the society in which the given visual language gains currency,” but he never effectively follows through the implications of such a perception. It is time to turn to Roland Barthes, the Barthes of Mythologies.

Barthes’ concept of “myth” can be defined by means of the famous example he offers. In a barber’s shop, at the time of the Algerian Uprisings and attempted suppressions, he picked up a copy of Paris-Match; on the cover a black soldier in uniform, was looking up, presumably at the French flag, and giving the salute. A simple image conveying, on the surface, a simple statement: here is a black soldier saluting the flag. But beyond the simple statement (the level of denotation), this simple signifier carries a wealth of surreptitious meaning (the level of connotation): the blacks are proud to serve the mother country, France; they are dignified and ennobled, and their lives are given meaning, by this service; imperialism is justified, indeed admirable, as it brings order, civilization, and discipline (embodied in the uniform) to the lives of the subject races (“natives” being by definition lax, unruly and childlike). In other words, the simple, seemingly innocent and “real” image (black soldiers do, after all, salute the flag of the country they serve) insidiously communicates at unconscious levels a political (here deeply reactionary) statement.

The Chase

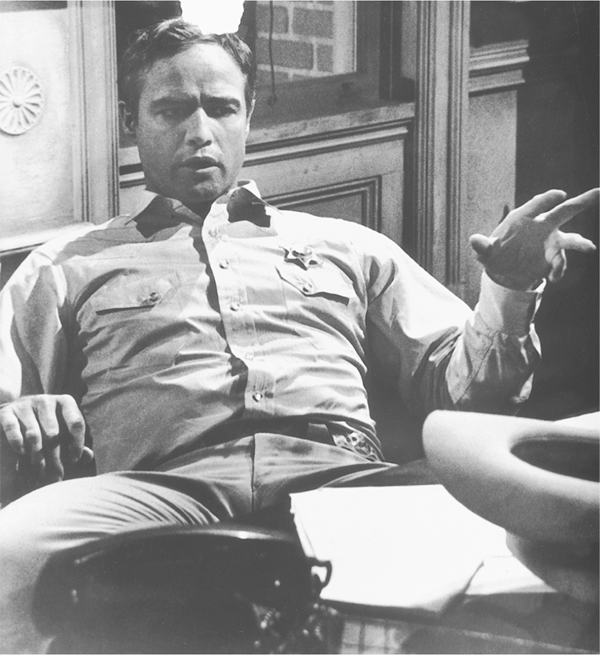

Marlon Brando as Sheriff Calder

Jane Fonda and James Fox in the wrecked-car dump

To Gombrich’s invaluable concept of schemata, then, it is necessary to add Barthes’ concept of myth—roughly speaking, schemata with their political dimension restored, the image as purveyor of ideology. Applying the notion of myth to the recurrent schemata of the Hollywood cinema, one recognizes the full significance of the obvious point that no direct connection exists between Young Mr. Lincoln and The Chase. What is involved is far greater than a specific resemblance based on chance or influence between two films made about twenty-five years apart: the schemata belong to the culture and carry cultural meanings which the two films variously inflect, the inflections determined not merely by two auteurs but by the complex cultural-historical network within which they function.

We can now consider the ten schemata, starting from the position that both films (vehicles of myth from the Classical and post-Classical periods respectively) are centrally concerned with America.

1. The male authority figure, the symbolic Father, repository and dispenser of the Law, combines myths of individualism and male supremacy that are central to capitalist democracy, enacting the functions of control and containment. In Ford’s film, Lincoln quells the lynch mob (that doesn’t break in to the jail), subsequently solves the crime and saves the lives of the Clay brothers, restores the family, and walks out of the film to become President of the United States. In The Chase, Calder fails to control the mob (the unruly respectable citizens break into the jail and beat him to a pulp), fails to save the young man’s life, and drives out of the town defeated on all fronts. Lincoln from the outset knows by some kind of Divine Grace that he will succeed, confidently presenting himself (despite his total inexperience) to Mrs. Clay as “your lawyer; Ma’am”; all Calder’s assertions of confidence prove unfounded (for example, his assuring Lester of the safety of the jail, where “we won’t have any of our citizens bothering you”: Lester is savagely beaten in his cell by the town’s supreme citizen, Val Rogers). Lincoln, above all, maintains his control over himself; Calder loses even that, succumbing finally to the all-pervasive hysteria and violence in his beating of the man who shoots Bubber Reeves. The collapse of confidence in patriarchal authority is also variously inflected in the presentation of Val Rogers and Mr. Reeves, whose ineffectual, last-minute attempt to make contact with his son by addressing him as “Charlie” provides one of the film’s most poignant moments.

2. In Young Mr. Lincoln Ann Rutledge dies but lives on as the protagonist’s spiritual support (it is “her” decision—the stick falling toward the grave—that sends him to study law). The myth of woman as man’s supporter/inspiration/redeemer is of course long-standing; The Chase does not explicitly challenge it, presenting Ruby as intelligent, sympathetic and (above all, and sufficiently) a wife. Yet the myth makes sense only in relation to the myth of the patriarch: if the hero’s charismatic and legal authority becomes invalid or ineffectual, the myth of woman-as-supporter collapses with it. Hence the emphasis on Ruby’s helplessness: locked out of the cell in which Val Rogers beats up Lester, she is subsequently locked out of the room in which the respectable citizens beat up her husband, and is finally unable to restrain Calder when he surrenders to the epidemic of useless violence. Where Lincoln leaves the film under Ann’s spiritual guidance to become President, Calder leaves the town under Ruby’s supervision (“Calder … let’s go”) to drive—nowhere. Ruby’s last line itself relates significantly to an obstinately recurring motif of the American cinema, the line (invariably spoken by the man to the woman) “Let’s go home” (or variations on it: “I’ll take you home,” “We can go home,” etc.) Here, the man no longer has the authority to utter it, and there is no home left to go to.

3. In Young Mr. Lincoln the innocence of the young accused is unambiguous: the brothers, representing simple “manly” virtues, are central to Ford’s idealization of the family, the celebration of family life being central to the film. Bubber’s innocence is far more equivocal: if he escapes the pervasive ugliness and corruption of the society, his chief characteristic is confusion on all levels, as shown by Emily’s describing his stare “like everything’s going wrong and he just can’t figure out why.” If Matt Clay represents a confidence in the values of the American pioneer past, Bubber, though among the film’s more positive characters, represents an uncertainty about the values of any possible American future.

4. Ford presents the lynch mob as essentially good citizens whose energies (finding release, initially, in the Independence Day celebrations) get temporarily out of control. They need to be reminded of what is “right”—of a fixed and absolute set of values ratified by biblical text—whereupon their basic soundness is reaffirmed. Their violence is taken as given, a fact of nature that demands no explanation, as unquestionable as the morality that subdues it. Such simple dualism has become impossible in The Chase: the violence is merely the logical eruption of the corruption, frustration and entrapment of the society. The citizens can no longer be told, effectively, to go home to bed (they would scarcely know which bed to go to); there are no texts, no absolute morality, to which appeal can be made. Further, the constitution of the mob is now quite different. In Lincoln it is composed of on earthy, vigorous proletariat still in close spiritual touch with the original cabin-raisers; in The Chase it is composed of the dominant classes, the affluent upper-middle and upwardly mobile middle, the wealthy patriarch Val Rogers (who virtually owns the town) in their midst. Calder’s own position, unlike Lincoln’s, is itself compromised: he owes his appointment as sheriff to Rogers and, however he may struggle to preserve his personal integrity, is never allowed to forget the fact.

5. Ford’s idealization of motherhood is central to Young Mr. Lincoln and to the ideology it embodies. The mother is reverenced as the rock on which the family, hence civilization, is built, and she never has to ask herself, like Mrs. Reeves, “Where did I go wrong?” At the same time she has no voice, no potency, in the male-dominated world of money, law, authority. Her simplicity (the guarantee of her sanctity and moral strength) is repeatedly stressed: she can’t read or write. By the time of The Chase, confidence in this central, supportive role has crumbled away. It is remarkable that, given the very large number of characters of all ages in the film, there is only one mother: Mrs. Reeves, hysterical, ineffectual, consistently wrongheaded, ultimately rejected by her son. This collapse of confidence in the figure of the Mother (for Ford, the spiritual core of civilization) points directly to a collapse of confidence in the family structure and, beyond that, in traditional sexual relationships generally.

6. It follows from Ford’s veneration of the mother that nothing in Young Mr. Lincoln questions the rightness and sanctity of marriage: Hannah, waiting anxiously, dutifully and passively for the outcome of the trial, is simply the Abigail Clay of the next generation. Against this we may set Anna Reeves and the uncertainty about traditional marriage ties introduced through her relationship with both Bubber and Jake Rogers. Her eventual commitment to Bubber carries considerable moral force (as does her active and forceful participation in events), but it has nothing to do with the sanctity of the marriage tie: she realizes that it is Bubber who really needs her.

7. In Young Mr. Lincoln the bible (and its later substitute, the Farmer’s Almanack—God and Nature conceived of as one) is the ultimate sanction, and Lincoln’s authority is seen as God-given; in The Chase, religion is reduced to the helpless, absurd and annoying mumblings of Miss Henderson, who is represented as mad. It no longer underpins and validates the system; it has become marginal to the point of irrelevancy.

8. The link between violence and male sexuality, which is implicit and probably unconscious in Young Mr. Lincoln, is fully explicit in The Chase. Ford’s work is consistently preoccupied with the ways in which “excess” energies can be safely contained (communal work, communal dances and celebrations, communal comic brawls), much of its complexity arising from the fact that both the energy and the forms of containment are highly valued. By the time of The Chase, all sense of the worth of the culture in whose name the containment is enforced has been undermined, and the energies themselves are seen as corrupted. Against Ford’s dances—celebration of energy and community—set The Chase’s three parties, which culminate and coalesce in the destructive chaos of the fireworks display in a wrecked car junkyard: sexual games, erupting into games of violence, which escalate in turn into real violence ending in total and irreparable breakdown.

9. Lincoln’s progress in Ford’s film is stimulated by his learning from the books passed on to him by the Clay family: he is guided toward his destiny as President by Ann Rutledge and Blackstone’s Commentaries, by women and nature, law and learning. In The Chase the concept of progress through learning has been debased to status-seeking display (the competitive money grants for the university) and hypocrisy (the remark that “only through learning is progress possible” delivered as an empty platitude).

10. Hollywood’s emblems for a lost innocence/happiness suggest a steady descent into disillusionment. Ann Rutledge, though dead, becomes the spiritual support of Lincoln’s career; Kane’s “Rosebud” epitomizes not only a lost childhood but an alternative, perhaps more fulfilling life uncorrupted by power. By 1956 “the river” of Written on the Wind represents only the illusion of past happiness (even as children, the characters were never really happy). In The Chase, the emblem of a nostalgically viewed childhood innocence has become an irreparably ruined, skeletal shed.

The Chase amounts to one of the most complete, all-encompassing statements of the breakdown of ideological confidence that characterizes American culture throughout the Vietnam period and becomes a major defining factor of Hollywood cinema in the late 60s and 70s. It achieves this as a Hollywood film: the ideological shift registered in the use of the ten schemata I have presented goes far beyond any overt social-political comments (on the position of blacks, etc.), which, like Penn, I find somewhat crude and obvious (though they make their contribution to the overall structure). It is the first “American apocalypse” movie, the first film in which the disintegration of American society and the ideology that supports it (represented in microcosm by the town) is presented as total and final, beyond hope of reconstruction. The ideological force of all the available schemata taken up by Ford in Young Mr. Lincoln (and therein celebrated as myths) is here definitively undermined.

Yet the work of the film is not merely negative: out of the collapse, a new positive movement, though extremely vulnerable and tentative, begins to manifest itself. One sees this most plainly in the attitude the film defines toward sexuality and sexual organization. The question “Do you believe in the sexual revolution?” is explicitly raised in the dialogue, and it seems fitting to conclude a discussion of The Chase by attempting to define the answer the film provides.

Three attitudes to sexual relationships are dramatized in The Chase, two of which are defined very clearly, the third remaining tentative and somewhat confused.

1. Traditional patriarchal monogamy: the Calders, Mr. and Mrs. Briggs, Mr. and Mrs. Reeves. The Calder relationship seems to be endorsed by the film—it is presented as strong, stable, and mutually supportive. Yet if patriarchal authority is overthrown, the ideological strength of the relationship logically falls with it. The film sets up fascinating parallels between the Calders and the Briggses: the monogamy of both relationships is emphasized, along with the subordination of the woman to the man; the barrenness of both is made explicit (Ruby wonders if they should have adopted children, Mrs. Briggs wonders whether having children or not having children is worse); Calder and Briggs are the only two who respect the law (Calder’s caustic “That makes two of us”). The Calders are presented positively, the Briggses negatively—opposite poles of the film’s value structure. This makes even more interesting the sense that the latter are a dark reflection of the former. There is a marvelous moment when the two main sexual worlds of the film make passing contact, the moment when Briggs (his wife as usual in tow, hanging on his arm) comments to Emily outside her house on the “permissive” behavior at her party (“Changing partners?”), and adds “But my wife and I, we’re old-fashioned.” As he says it, Mrs. Briggs stares at him with a look bordering on pathological hatred: it brilliantly epitomizes the repressiveness of patriarchal monogamy and the frustrations of women within it. The Reeves couple appears to offer the inverse of this with the woman as dominant partner, but is more accurately a variation on it: all Mrs. Reeves’ emotional energy has been displaced on to her male child, hence her hysteria when he “goes wrong.” If the Calders are viewed as heroic, the overall sense of the film reveals them as defending a system that has become obsolete. Finally, all they can do is drive away from the ruins.

2. Permissiveness: the ‘sexual revolution’ as understood by the Fullers, Stuarts, etc., taking the form of squalid and furtive adulterous intrigue undertaken for its own sake, out of boredom, frustration or a desire to get even with one’s spouse, with a strong insistence on phallocentrism (Edwin “doesn’t have a pistol,” Damon obviously does). If the film implicitly undercuts traditional monogamy, it openly attacks this permissiveness as purely destructive and motivated by destructiveness, rather than by any impulses of concern, tenderness or generosity. Yet permissiveness is clearly but the other side of the coin (suggested by the Briggs/Emily exchange referred to earlier)—the logical result of the collapse of repressive and artificial proscriptions.

3. The attitude dramatized in the Bubber-Anna-Jake triangle. During the episode in the junkyard the three try to work out what is potentially a new morality (it is significant that the film roughly coincides with the growth of the hippy movement): a genuine new morality, as against the immorality fostered (“permitted”) by the old morality. Central to it is Anna’s recognition that she is able to love two men at once, her relative autonomy of choice, decision and action (unique among the women of the film), and Bubber’s acceptance of her and Jake (his wife and best friend) as lovers. This goes against both traditional monogamy, by rejecting its artificially imposed, legalized repressiveness, and permissiveness, by rejecting its egotistic heartlessness and phallocentrism. Monogamy and permissiveness are both based upon an obsession with sexuality (the one with its containment, the other with its supposedly free expression): within both arrangements, sex becomes the central criterion by which behavior is judged, the notion of fidelity or infidelity restricted to the simple act of intercourse. The Bubber-Anna-Jake story enacts the tentative dethronement of the sexual act, without at all diminishing the importance of sexuality as human communication. It suggests that sexuality is not incompatible with friendship, with sharing, with an unrestricted human concern. Significant in relation to this is the older generation’s total inability to understand or predict the behavior and motivation of the younger characters. Hence Val Rogers assumes without hesitation that Bubber will kill Jake when he finds out that he and Anna are lovers; hence Mrs. Reeves can find no word for Anna but “whore.” Anna—her activeness, her autonomy, her refusal to allow herself to be defined by a relationship with a man—is at the heart of the film’s tentative, uncertain positive movement.

Herein lies the appropriateness of the ending as it stands, albeit unsanctioned by the film’s director, an appropriateness both within and outside the fiction. The Calders drive away, defeated. The film abandons them to end on Anna Reeves, the character, still able to learn, reflect, develop, and Jane Fonda, the actress, walking toward her problematic future career, both cinematic and political. Like young Mr. Lincoln, she walks out of the frame, leaving behind a film and a society that can no longer comfortably contain her.

1. The format of this essay makes it awkward to incorporate the names of the actors in the text (the practice elsewhere in this book). The characters referred to are played as follows: Sheriff Calder: Marlon Brando; Ruby Calder: Angie Dickinson; Anna Reeves: Jane Fonda; Bubber Reeves: Robert Redford; Val Rogers: E. G. Marshall; Jake Rogers: James Fox; Edwin Stuart: Robert Duvall; Emily Stuart: Janice Rule; Damon Fuller: Richard Bradford; Mary Fuller: Martha Hyer; Mrs. Reeves: Miriam Hopkins; Mr. Reeves: Malcolm Atterbury; Mrs. Briggs: Jocelyn Brando; Mr. Briggs: Henry Hull; Mrs. Henderson: Nydia Westman.