NOTES TOWARD THE EVALUATION OF ALTMAN (1975)

Obviously, Altman is “in.” Highly favorable articles on his work proliferate on both sides of the Atlantic, from Pauline Kael’s premature ecstasies over Nashville in the New Yorker to Jonathan Rosenbaum’s more modest assessment in Sight and Sound that Altman, while “he really cannot be considered in the same league at all” as Rivette or the Tati of Playtime has “opened up the American illusionist cinema to a few of the possibilities inherent in this sort of game:” the game being, apparently, “the notion that artist and audience conspire to create the work in its living form.” It is a conspiracy in which I have so far failed to participate, finding works either created or not, as the case may be. If the film isn’t up there on the screen “in its living form,” I don’t feel there is much I can do about it. I view Altman with mixed feelings, finding most of the films interesting and a very small number very good. Nashville—an enormously ambitious work, a kind of War and Peace of country and western—may well prove the decisive film of his career, a watershed like Losey’s Eve, a definitive statement of artistic identity from which there is no turning back. As with Eve, its unpleasantness casts a certain retrospective shadow over the films that preceded it, highlighting features to which one has not previously attributed great importance. It seems likely to be hailed as a masterpiece, and Altman’s films are already on the way to that fashionable acceptance where criticism ceases to ask questions and lapses into a celebration of excellences. With the release of Nashville, it seems the right moment to take stock of Altman’s achievement so far, to attempt to sort out strengths and weaknesses, and to ask how they relate to each other.

The particular interest of Altman’s work derives from a complex of attributes, central to which, of course, is the intrinsic quality of his best films. He is already clearly identifiable as an auteur, with certain themes, structures, attitudes, and stylistic features (not to mention his familiar stock company of actors and collaborators) recurring across a wide range of genres and subject matter. Michael Dempsey provides a good definition of Altman’s auteurship in an article called “The Empty Staircase and the Chinese Princess” in Film Comment (September-October 1974), and I am in almost complete agreement with his relative evaluation of the films (I think he is too generous to Images and too hasty in his dismissal of California Split). Counterpointing this sense of auteurist consistency, in fact, is one’s sense of the extreme unevenness of Altman’s work—unevenness that can’t be accounted for neatly in terms of the external excuses the commercial cinema traditionally provides (studio interference, imposed projects, incongruous casting, etc.), because the worst films are just as personal as the best and because Altman’s control over his work (at least in the material sense) seems always to have been more or less total. He seems to me to have been responsible for some of the best (McCabe and Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye) and some of the worst (M.A.S.H., Images) films by American directors in the past decade, his other films covering the full range of intermediate success and failure between these.

Most important of all is the centrality of Altman’s work to the development of the modern American cinema. Because of its distinction, because of the presence of a clearly defined creative personality, it brings to a sharp focus most of the features that characterize that development: the growing sense of disorientation and confusion of values, with the consequent sapping of any possibilities for affirmation; attitudes to the Hollywood of the past and its traditional genres; awareness of the modern European cinema and the desire to assimilate its techniques; the change (also influenced by Europe) in the role and status of the director, from studio employee to (at least in theory) all-determining artist. An attempt to define Altman’s work in thematic terms will inevitably spill over into an exploration of the dominant themes of the American cinema today. During a discussion in Movie 20, Victor Perkins remarked that a thematic description of Nicholas Ray would closely resemble one of Kazan. The same could be said now of (to name but three of the most distinguished contemporary figures) Penn, Altman and Schatzberg. Close parallels can be drawn, for example, between Puzzle of a Downfall Child and Images, and between Scarecrow and California Split. In both cases—in the former decisively—the comparison would be, in my opinion, to Altman’s disadvantage, but my point is that, for all the changed status (more perhaps an appearance than a reality, but not entirely illusory) of the director as artist-expressing-himself, one cannot sensibly discuss any of these films without placing them in a wider context, that of the movement of the American cinema and, beyond it, American society.

Since the early 60s, the central theme of the American cinema has been, increasingly, disintegration and breakdown. On the most obvious and vulgar level, it is expressed in the recent cycle of disaster movies in which the threat of total destruction is faced by a microcosm of bourgeois-capitalist society (the working classes and the student population scarcely, if at all, represented: a most significant suppression, the disaster standing in for social revolution). Being expensive super-productions, producers’ rather than directors’ movies, studio-dominated with a minimal intervention of individual creativity (which is almost invariably disruptive to some degree), the films are very strongly determined by status quo ideology, hence are as much survival pictures as disaster pictures, concerned to demonstrate capitalist society’s ability to come through. Even their expensiveness is a comforting assertion of the stability of the capitalist system. Yet the necessity for this not very convincing insistence on survival is itself eloquent. Meanwhile, various genres have reached their apocalyptic phase, most significantly that reliable barometer of America’s image of herself, the western—a development instigated by The Wild Bunch and confirmed by Eastwood’s crude but remarkable High Plains Drifter wherein the Lone Hero rides in from the Wilderness not to defend the Growing Community but to reveal it as rotten at its very foundations before annihilating it. In the discussion in Movie 20, somebody asked what had become of the American Family Picture. I suggested Night of the Living Dead and The Exorcist. I might have added Rosemary’s Baby, which seems to occupy the place in the development of the American horror film that The Wild Bunch occupies in the development of the western—they appeared in the same year. Most opportunely, the release of It’s Alive, in which the Ideal American Family itself gives birth to a destructive monster, adds vivid confirmation.

The sensation of imminent or actual breakdown, of rottenness at the ideological core of capitalist society, presented with such irrefutable pervasiveness by the popular cinema, is explored more consciously and intellectually in the work of directors like Penn, Schatzberg and Altman. Nashville is, in fact, the supreme example of the spiritual-intellectual disaster movie, with that multi-plot, multi-character structure essential to the genre, Nashville itself being, like the ship of The Poseidon Adventure, the plane of Airport 1975, the skyscraper of The Towering Inferno or the Los Angeles of Earthquake, an image of America, though much more pessimistically conceived, with the notion of survival (as epitomized in the crowd’s final mindless chanting of “It don’t worry me”) become bitterly ironic. The process of disintegration provides the characteristic movement of the films of all three directors, whether it is located within a single disturbed personality (Mickey One, Puzzle of a Downfall Child, Images), a social milieu or community (The Chase, Alice’s Restaurant, Nashville), or a personal relationship (Night Moves, Panic in Needle Park, Scarecrow, California Split).

Consider the cases of Scarecrow and California Split. Both belong firmly within that most curious and characteristic of contemporary subgenres, the “male duo” movie, a phenomenon that has yet to be sufficiently explained. Though there are of course antecedents (notably in Hawks), the cycle was decisively inaugurated by Easy Rider and Midnight Cowboy, and has proved strikingly prolific and generally popular (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Little Fauss and Big Halsey, Bad Company, When the Legends Die, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, etc.) It can be regarded as a response to certain social developments centered on the emancipation of women and the resultant undermining of the home. The implicit attitude is “You see, we can get on pretty well without you, anyway—except as occasional sex objects.” Certainly, women play very peripheral roles in the films, most of which have homosexual overtones, usually suppressed or ambiguous. The surface emphasis is always on the camaraderie between the two men, the detailed, high-spirited give and take, offering opportunities for improvisatory acting and self-expression to two gifted players. But the seductive charm of the surface play invariably conceals absences. The films take the form of journeys with complicated, rambling, usually aimless itineraries—journeys to nowhere, searches in which the real object of the search remains undefined or uncertain. In both Scarecrow and California Split one of the protagonists is linked, albeit tenuously, with a home: in Schatzberg’s movie, Al Pacino clings tenaciously to the illusion that he can return whenever he wishes, after years at sea, to the wife and child he has abandoned; in Altman’s, George Segal’s disorientation and rootlessness have for background a recently broken marriage. Both films move toward a point where the characters become aware of the sense of loss—a culmination movingly realized in Scarecrow, lightly touched on in California Split, where Segal, having won a fortune gambling, abruptly grasps that it means nothing to him and announces that he’s going “home.” The understated poignancy of the ending derives from our awareness that he no longer has a home to go to.

The difference between the two films lies in the much greater emphasis on surface charm in Altman’s: where Schatzberg is committed to exploring his characters and their predicament (and seems to care much more about them), Altman is more interested in playing improvisatory games with his actors. California Split is the more immediately appealing movie, Scarecrow the more substantial. Altman’s tendency to allow himself to be seduced by surface play, and to use it to seduce audiences, is one aspect of the strategies of evasion that characterize his work. The distinction, however, is also bound up with certain issues in the realism/antirealism debate, In Scarecrow we think primarily of the actors as characters; in California Split we are much more aware of them as Themselves (especially the irrepressible Elliott Gould). I shall return later to the antirealist elements in Altman’s work, which represent its most obviously problematic aspect.

This sense of collapsed or discredited values is reinforced if one juxtaposes Thieves Like Us with They Live by Night, Ray’s 1948 version of the same novel. One’s immediate impression is that the Farley Granger/Cathy O’Donnell couple represents a much more bourgeois-romantic concept than that embodied in the casting and direction of Keith Carradine and Shelley Duvall. Ray was still able to half believe in certain bourgeois values of stability, home, family (see also The James Brothers). Behind the riven bourgeois families of Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger than Life there hovers a traditional norm of the healthy family, which is reaffirmed (necessarily without carrying full conviction) at the ends of the films. In Altman, Schatzberg, recent Penn, this has largely disappeared (in Bonnie and Clyde it had already become a pale ghost, little more than a pathetic illusion, an idea expressed visually in the scene of the reunion with Bonnie’s mother). The broad changes in the way in which the American cinema interprets the American past might also be adduced: in 1940 the Joads could still trek through the Depression to at least a hypothetical Promised Land; the aimless itinerary through the Depression of Thieves Like Us leads only to the empty staircase justly emphasized by the title of Michael Dempsey’s article. They Live by Night gains from its basis in traditional values (however qualified by Ray’s critical irony), not because the values were “true,” but because they provided a tension that Thieves Like Us lacks; for all the intelligence at work in individual scenes, the overall effect is curiously empty and lacking in dynamism, an almost academic demonstration of futility.

The most persistent recurrent pattern in Altman’s films—their basic auteurist structure—constitutes a personal inflection of the general thematic of the contemporary American cinema. The protagonist embarks on an undertaking he is confident he can control; the sense of control is progressively revealed as illusory; the protagonist is trapped in a course of events that culminate in disaster (frequently death). The pattern is already embryonically present in the astronaut of Countdown (James Caan)—though there the film has a last-minute, ideologically obligatory happy ending. It is expounded fully in That Cold Day in the Park: a spinster (Sandy Dennis) takes in a hippy (Michael Burns) whom she sees from her apartment window, huddled on a park bench in the rain; each believes him/herself to be in control of the situation that develops, she by adopting an attitude of maternal but pseudo-permissive protectiveness that conceals her sexual drives, he by totally withholding speech, hence remaining mysterious (the audience is uncertain until about a third through the film whether he can speak or not). In fact, their sense of control (over each other, over the relationship, over themselves) is dependent on very limited awareness; they are mutually involved in a process that culminates in breakdown and murder. The loss of control is epitomized in the moment when Sandy Dennis drives a carving knife into the heaving bedclothes, not knowing whether she is stabbing the boy or the whore with whom she has provided him.

The Altman protagonist characteristically has, whatever his age, an adolescent quality, a combination of arrogance and vulnerability: McCabe, Marlowe in The Long Goodbye, Bowie in Thieves Like Us, Elliott Gould in California Split, Keith Carradine and the young assassin of Nashville are all obvious examples. The archetype is Brewster McCloud (Bud Cort), the boy who believes he will be able to fly. From the point of view of the audience, the character’s assumption of control is undermined from the outset, the product of immaturity and ignorance. This partly accounts for the relative lack of dynamic tension in Altman’s films, both in overall structure and in the detail of individual scenes—relative, that is, if one compares not only Thieves Like Us with They Live by Night, but The Long Goodbye with Night Moves, or, again, California Split with Scarecrow. M.A.S.H., while it in some ways reverses the Altman pattern (the heroes survive and come out on top), displays this characteristic lack of dynamic tension to an extreme degree: its heroes’ resilience is purchased at the price of a total and unquestioning acceptance (theirs and Altman’s) of their own arrested adolescence, which the film seeks to justify by an equally unquestioning and glib acceptance of a sort of debased existential absurdism.

While the personal basis of Altman’s choice of protagonist can scarcely be doubted (it is too consistent through the films and too consonant with their general attitudes), it may also be partly determined by the more general quandary of the antiestablishment director in the American commercial cinema: only certain types of protagonists are available to him. Figures such as Penn, Peckinpah, Schatzberg and Altman are in somewhat the same position as Godard up to Pierrot le fou: rejecting the established society in which they live but having no constructive social/political alternative to offer, their logical gravitation is to the outsider, the outcast, the criminal. By inhibiting the growth of a social dimension in their work, this in turn, places inevitable barriers in the way of development and makes it difficult to sustain the affirmative impulse so essential to a flourishing creativity. To this can be partly attributed the increasing desperation, perfunctoriness and self-parody of Peckinpah’s work since Junior Bonner, the recourse to the ineffectual adolescent hero in Altman’s, the long hiatuses in Penn’s (though he alone of these directors, with much the strongest sense of social responsibility, has consistently tried to explore alternative concepts—the hippies of Alice Restaurant, the Cheyenne of Little Big Man). The path taken (for better or for worse) by Godard since Pierrot le fou is by definition closed to anyone who wishes to continue working in the commercial cinema, and would in any case be particularly difficult to follow in America. The Longest Yard (The Mean Machine) is probably the closest the American commercial movie can get to a genuine revolutionary cinema—which to say, scarcely closer than Z. Its subversiveness is qualified by characteristically Fascist overtones (the People turn out to be helpless without their Leader), but Aldrich has certain useful negative prerequisites for the development of a revolutionary mentality—a natural coarseness of sensibility combined with a total lack of interest in the cultural tradition.

It is doubtless this question of temperament that makes it possible for the revolutionary critical fraternity to continue to take an interest in emotional barbarians like Aldrich and Fuller while showing almost none at all in Penn, Schatzberg and Altman, all of whom are hampered, from this viewpoint, by a comparatively civilized sensibility. One aspect of this is their evident attraction to the European cinema, with its concept of film as a personal art, its enthronement of the director as artist, its encouragement of artistic consciousness (or self-consciousness) The debt of Bonnie and Clyde to the New Wave, for example, has become critical commonplace; that of Puzzle of a Downfall Child to Bergman, Resnais, and Fellini (not to mention Welles) is even more obvious—or would be if anyone had the chance to see Schatzberg’s remarkable first film, which is so much better than an account of its derivations suggests. The richness of Altman’s best films, as well as the meretriciousness of his worst, derives partly from his cultural schizophrenia: obsessed with America and with being American, he casts continual longing looks to Europe. At its worst, his hankering for European models expresses itself in cheap opportunistic borrowings that deprive the originals of all their complexity: the “Last Supper” pose in M.A.S.H., the Makavejev effects (notably René Auberjonois’ recurrently intercut bird lecture) in Brewster McCloud, the use of Romeo and Juliet to accompany and counterpoint the love-making in Thieves Like Us (surely traceable to the English lesson in Bande à Part). What is interesting here is not the effect Altman achieves but the relative resourcefulness of the gleanings—Buñuel, Makavejev, and Godard, instead of the usual Fellini (though he turns up too in the circus finale of Brewster McCloud).

But the European influence in Altman’s work is more interesting, more pervasive, less direct, than this suggests. His worst films, interestingly, represent the polar extremes of his work: the purely American, TV-style M.A.S.H., the imitation European art movie Images. His best films are hybrids, products of a fusion of “European” aspirations with American genres. The Long Goodbye has more in common with Blow Up than with The Big Sleep, but nevertheless draws sustenance from the genre Altman supposed himself to be satirizing. The sophisticated visual style of McCabe and Mrs. Miller repeatedly invites comparison with painting (the Degas-like scene of the whores’ bath, for instance), and the use of Leonard Cohen’s songs, more as counterpoint than accompaniment, has a complexity and sophistication beyond what one is accustomed to in western scores. But the film has its place in the mainstream of the development of the genre. It offers particularly suggestive points of comparison with My Darling Clementine, the opportunistic entrepreneur McCabe replacing the ideologically committed Earp, Mrs. Miller replacing Clementine as the “girl from the East,” the whorehouse replacing the church as the center of the growing community, the melancholy shoot-out in the snow replacing the gunfight at the OK Corral.

The elaboration of an immediately recognizable, self-assertive personal style seems no more common in the American cinema today than it was in the heyday of the studio system: style, that is, has become much more assertive but no more personal. Both the technical means (e.g., the zoom lens) and the stylistic determinants (e.g., television and commercials) have changed, but the average film is no less anonymous than it used to be. It is beyond the scope of the present chapter to account satisfactorily for the complex of factors—ideological, economic, technological—determining the general stylistic features of the modern American cinema (the sort of work one hopes to see done in Screen). What most interests me (and it is a development to which, again, Altman’s work is central) is the way in which the movement toward that particular variety of realism associated with deep focus photography has been reversed. Deep focus offered the spectator the illusion of natural perspective, the effect (always qualified in Welles by the disorientating rhetoric of Expressionist angles and ostentatious camera movement, but much cultivated by the arch-bourgeois Wyler) of a stable world of real spatial relationships. Today space is habitually flattened by the telephoto lens, and perspectives are no longer stable: focus pulling and the use of the zoom have become permissible, indeed, standard, overt devices.

The overtness is the point. Such devices as focus pulling were not alien to the Hollywood cinema of the past, provided they were cunningly concealed, effectively invisible. As Madame Constantin descends the stairs toward Ingrid Bergman in a long held subjective shot in Notorious, the background gradually goes out of focus as she approaches the camera, and a long shot becomes a close-up, but the audience, intent, like Ingrid Bergman, on attempting to read the woman’s face, is quite unaware of this. Compare any of those moments to which we are now so habituated (Sandy Dennis’s awareness of Michael Burns from her apartment window as she entertains guests to lunch at the beginning of That Cold Day in the Park is a good example) in which the audience’s focus of attention is deliberately shifted by a shift of focus within a shot.

The implications of such changes cannot be formulated simply. They are clearly bound up with what Victor Perkins called “the death of mise-en-scéne,” a remark dependent on a definition of mise-en-scéne that would stress the relative invisibility of the director and of technique, the strict subordination of style to the action. The changed status of the director is also relevant: a Kubrick, a Peckinpah, an Altman is encouraged to assert his presence in the film—or at least has to fight for his right to do so against less unfavorable odds than was the case for von Sternberg or Welles. Most fundamentally, however, and closely connected with this, the stylistic changes in the American cinema imply a tacit recognition that the “objective reality” of the technically invisible Hollywood cinema was always a pretense, a carefully fostered illusion—an admission that all artistic reality is subjective. For all the stylization of the action and the very particularized Hawksian world, it was still possible to watch Rio Bravo as if one were looking through a window at the world: nothing overtly intervenes between the spectator and the action. The Long Goodbye is “a film by Robert Altman”—we cannot escape the director’s omnipresent consciousness. The implicit statement is no longer “This is the way things happen,” but “This is how I see the world.” Yet if all reality is subjective, all certitude is impossible.

Though he is less obviously in the forefront, Altman (within the context of the American commercial cinema) bears something of the same relationship to the zoom/telephoto lens as Welles to deep focus and Ray to CinemaScope: he didn’t invent it, but his peculiar genius has enabled him to grasp and realize its expressive potentialities. The zoom is central to the change in the relationship of audience to film. Its significance lies in its obtrusiveness: directors who use the zoom “tactfully,” trying to make a zoom-in indistinguishable from a tracking shot, are not really using it at all, but are trying to suppress its particular properties. For Altman, the zoom is at once his means of guiding the audience’s consciousness and of asserting his own presence in the film; but he has also grasped its potential for dissolving space and undermining our sense of physical reality. Frequently associated with his use of it is the most immediately striking phenomenon of his style, the obsession with glass surfaces, windows, mirrors. This again is scarcely new in the American cinema: it is a feature of a certain “baroque” tradition (one thinks of von Sternberg, Welles, Sirk, Losey). Yet in Altman it is given a new dimension of stylistic assertion. One can sit through Written on the Wind or Imitation of Life “for the story,” without necessarily becoming conscious of the mirror shots as such, because they are always integrated in the action, a part of mise-en-scène before it died; the same could scarcely be said of That Cold Day in the Park (where Altman repeatedly zooms in to glass cabinets and glass shelves that have no immediate bearing on what is happening) or The Long Goodbye (in one scene of which spatial reality is dissolved in a bewildering ambiguity of reflecting surfaces).1 The difference is important: in the Sirk films, the audience is invited to contemplate a world (which is presented in clear images with analytical precision) in which characters are uncertain of their own reality; in The Long Goodbye, the uncertainty is assumed to be shared by the director and by the audience; it has become part of the method and texture of the film as well as its subject matter.

One can reinforce the point, and suggest its wider significance in terms of the development of the American cinema and American society, by comparing The Long Goodbye and Night Moves (and one might add, among other films, The Conversation) with their forerunners, the private eye movies of the 40s. Altman and Penn leave areas of unresolved doubt as to the various degrees of guilt and the precise motivation of certain of their characters: the tendency is more extreme in Night Moves than in The Long Goodbye, but after repeated viewings I am still uncertain as to the precise nature of Eileen Wade’s involvement in the intrigue and the extent of her culpability. In The Conversation Coppola seems to play at one point on the assumption that the spectator will doubt the evidence of his own ears as much as the undermined protagonist—the shift in emphasis, in a crucial sentence on the tape, from “He’d kill us if he got the chance” to “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” A central point of the films has become the misguidedness or inadequacy of the investigator (who nonetheless remains our primary identification figure): Hawks’ Marlowe was not infallible, but Altman’s is infallibly wrong. With this goes, in both Penn’s film and Altman’s, a carefully cultivated and preserved moral uncertainty: it is not simply that the protagonist’s assumptions and decisions are called into question—the spectator too is prevented from forming secure judgments. Whatever we may deduce about Eileen Wade’s motivation and guilt, there is no longer any coherent moral position established in the film from which she might be judged. If she and her husband remain the film’s most moving characters, it is purely because they have the greatest capacity for suffering. We may occasionally, in the 40s have remained in some uncertainty as to the chain of events (The Big Sleep), but never as to what to think of the characters; one might contrast Bogart/Spade’s definitive dismissal of Brigid O’Shaughnessy in The Maltese Falcon with the equivocal Third Man ending (Altman’s analogy) of The Long Goodbye.

I suggested earlier that The Long Goodbye has more in common with Antonioni than with Hawks (the dope-taking, yoga-practicing nude girls who live across the way from Marlowe would be quite at home in Blow Up), and I have been struck by a similarity in the way Altman and Antonioni talk about their films. The theme they stress is the problem of adapting to the changed conditions of modern life, and they speak as if their protagonists were to be criticized for their failure to adjust (“Rip van Marlowe”). Yet the films never satisfactorily answer the unspoken question of what adjustment would entail: the world of ephemerality and promiscuity of L’Avventura, the dehumanized technological world of Red Desert, and the moral and emotional quicksands of The Long Goodbye offer little of a positive nature that could make adjustment seem desirable from any viewpoint but that of mere survival. The effect in The Long Goodbye is curious: one has the feeling that Altman despises “Rip van Marlowe” yet is very close to him—closer, perhaps, than he would wish to acknowledge. Red Desert gives the impression that Antonioni wanted to make a film that would place Giuliana’s inadequacies in a context, show her failure in relation to positive social possibilities, but that he was in fact so close to Giuliana that he was able to show the context only from the viewpoint of her inadequacies, colored (literally, at moments) by her neurosis. So with Altman and Marlowe. Marlowe, a child in a world of corrupt and dangerous adults, is incapable of making sense of anything and his every decision is wrong. Yet Altman can give the audience nothing else to latch on to except the experience of pain (the Wades): Marlowe, ultimately, is where he’s at. In both Antonioni and Altman, the gestures toward a progressive viewpoint thinly conceal despair and a sense of helplessness.

I have so far concentrated on Altman’s centrality to the development of the American cinema, though in doing so I have demonstrated inadvertently how description inevitably shades into evaluation. It remains to try to define more precisely the nature and quality of the sensibility expressed in Altman’s films. During the sequence in The Long Goodbye in which Marlowe is interrogated at the police station, there is a running discussion as to whether he is a “smart-ass” or a “cutie-pie.” The distinction between the two is less than clear-cut: presumably the “smart-ass” antagonizes while the “cutie-pie” seeks to disarm, but both use slickness or cleverness as a defense and an evasion. They express at once an assertion that one is in control and an inadvertent admission (because of their transparent inadequacy) that one is not. They are Marlowe’s means of evading not only the questions of the police but the need to try to understand things, to make sense of life. Smart-ass and Cutie-pie are both prominent in the artistic personality projected in Altman’s films. M.A.S.H. is dominated by them exclusively. If Aldrich and Fuller are emotional barbarians, M.A.S.H. makes one realize how preferable barbarism is to smart-ass sophistication, the barbarian being open to at least some of the tensions and complexities that the smart-ass of M.A.S.H. ruthlessly represses: neither Aldrich nor Fuller would ever descend to the way Altman treats the Robert Duvall and Sally Kellerman characters in that film. Apparently at the other extreme, Images in its trendy esoteric way is almost as dominated by this side of Altman: what could be more cutie-pie than the way all the actors exchange names (René Auberjonois as Hugh, Hugh Millais as Marcel, Marcel Bozzuffi as René, Susannah York as Cathryn, Cathryn Harrison as Susannah)? And the “surprise” ending (Cathryn thinks she has knocked her alter ego over the waterfall, but it turns out to be her husband) is just a cheap gimmick quite ungrounded in any realized psychological significance. It is striking that the film that seems most directly personal in its material (schizophrenia, and the dissolution of the sense of objective reality) should be the one (after M.A.S.H.) most dominated by Altman’s smart-ass defense mechanisms. Brewster McCloud provides ample evidence of the pervasiveness of Smart-ass and Cutie-pie, and of Altman’s readiness to surrender to them. The film has a kind of reckless inventiveness that is both endearing and maddening—really an inability to define a level of seriousness or engagement, so that one’s final impression, for all the film’s thematic richness and the intelligence intermittently at work, is of a glorified TV revue.

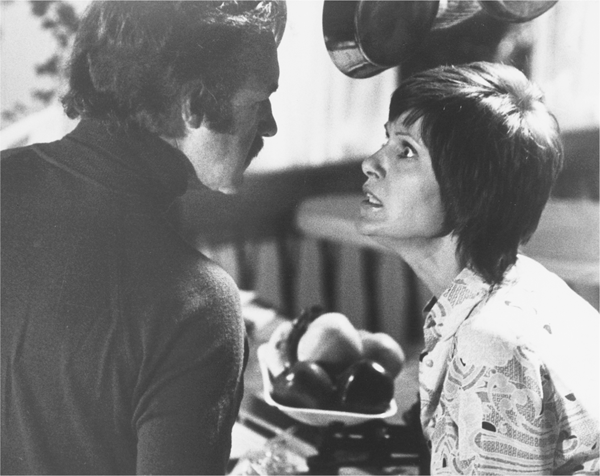

Marriage in 1970s Film Noir

Nina van Pallandt and Sterling Hayden in The Long Goodbye

Gene Hackman and Susan Clark in Night Moves

Smart-ass and Cutie-pie also intervene disconcertingly at moments in Altman’s better films. They are a constant threat in The Long Goodbye (in the use, for example, of the all-pervading theme song that even turns up as the chimes on Eileen Wade’s doorbell), but are just sufficiently “placed” by the pain and sense of confusion the film so impressively communicates. The most startling single eruption is in the lovemaking sequence of Thieves Like Us. Altman’s conception of the scene courts disaster: as Victor Perkins points out, the decor (song sheets plastered all over the walls) is in its obtrusiveness and insistence more distracting than expressive; the use of Romeo and Juliet on the radio is perilously obvious. Yet Altman almost makes it work, partly because his actors are so good, partly because the heavily ironic use of the play is made somewhat more complex by its radio vulgarization (complete with Tchaikovsky), so that it both evokes the original’s concept of absolute romantic love and is convincingly a part of the lovers’ debased environment. But Altman can’t leave well alone: he seems terrified that someone might still suspect him of being “romantic.” So, not once but three times, every time the lovers copulate, he has the radio announcer proclaim “Thus did Romeo and Juliet consummate their first interview by falling madly in love with each other.”

What is revealing about this is that the Bowie-Keechie relationship in Thieves Like Us is the only instance in Altman’s work so far of a successful sexual union (successful, that is, in terms of a developing mutual commitment). Everywhere else, sex is presented as either trivial or destructive or, occasionally, disgusting (the offensive use of lesbians in a scene in That Cold Day in the Park to elicit a stock response that rebounds, very simply, on Altman). The sexual relationships in Altman’s films that are movingly treated are either frustrated (McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Allen Garfield’s attachment to Ronee Blakley in Nashville) or embittered and mutually destructive (the Wades in The Long Goodbye). Significantly Brewster McCloud is destroyed by sex, which undermines his ability to fly. And Marlowe, of course, has only his cat (and loses that): his general impotence, though not made explicitly sexual, is repeatedly given sexual connotations through his helplessness in situations involving women (Joanne, Eileen Wade) and in contrast with the brutally sexual Terry Lennox.

The antirealist tendencies in Altman seem inextricably bound up with the Smart-ass elements. If one ignores matters of tone, devices like the interchange of names in Images or the use of the radio announcer in Thieves Like Us can be theoretically justified on antirealist lines, the former blurring the distinction between characters and actors, the latter disrupting our involvement in the fictional reality. Yet one has only to evoke Godard to recognize how spurious such justifications are. Consider, as a simple example, certain of the non-diegetic elements in Le Mépris—the shots of Brigitte Bardot in nude Playboy-style poses inserted into the long central dialogue in the apartment. The film’s fictional narrative is centered on the theme of prostitution (in the wide, Godardian sense): the inserted nude shots fulfill the truly Brechtian function of extending the audience’s awareness outside the diegesis, but without loss of thematic relevance, to take in Bardot’s public image, the “sexist” image of Woman, the producers’ demand that Bardot appear naked in the film, the spectator’s own demand to see her naked, the ambiguity of Godard’s position as “commercial” filmmaker. Altman’s antirealist devices, on the other hand, seem merely his defense against a too intense involvement in the fiction, the Smart-ass shrugging off of the responsibilities of engagement. They are part of a psychological-aesthetic complex of which the distrust of sexual involvement, the fascination with drugs (a motif in most of the films) and gambling (California Split), and the fondness for turning filmmaking into self-indulgent play with friends, at once disarming and evasive, are all aspects.

Only M.A.S.H., however, is completely dominated by Smart-ass and Cutie-pie, just as only in one film are they successfully dominated. Altman’s positive qualities are dependent on the precariousness of the defense-mechanisms. All his finest work is centered on the revelation of vulnerability and the experience of pain. His films are successful in direct ratio to the degree to which the Smart-ass element is assimilated and placed within the narrative structure, dramatized in the leading character (McCabe, Marlowe) and revealed as the inadequate defense of a very vulnerable man. Only in McCabe and Mrs. Miller (which is fed also by the richest of all American genres) are the conditions completely met. The Long Goodbye contains perhaps the finest scenes in Altman to date (those involving the Wades and, outstandingly, the scene of Roger Wade’s suicide, a locus classicus of resurrected zoom lens mise-en-scène), but in the last resort the film suffers from the fact that Gould’s Marlowe is simply too silly, too juvenile, to give the film the dynamic moral/emotional tension that makes McCabe and Mrs. Miller so far unique in Altman’s work: Marlowe’s smugness, unlike McCabe’s, is incorrigible. I have hinted that Marlowe is one of the characters to whom Altman seems closest—which may explain why he finds it necessary to express such contempt for his stupidity (the same thing happens, more extremely and disastrously, with the Geraldine Chaplin character of Nashville). Comparison with Night Moves is illuminating: the decisions and deductions of Penn’s hero are just as misguided as Marlowe’s, yet they are the mistakes of a confused adult rather than an arrested adolescent. Penn doesn’t feel it necessary always to be insisting on his own superiority to his protagonist.

Everything in Altman so far—the good and the bad—comes together in Nashville. Its great scenes—Gwen Welles’ enforced striptease, Ronee Blakley’s onstage breakdown, everything involving Lily Tomlin—are all centered on the characters’ exposed vulnerability and realized with painful intensity. At the other extreme are the embarrassingly Cutie-pie uncredited guest appearances of Elliott Gould and Julie Christie as Themselves. But Nashville’s central failure lies in the Geraldine Chaplin figure (“In a way, she’s me in the film,” Altman remarked in a rather startling moment during an interview on the set of the film, in Positif 166). The character is central to the film’s structure: as Altman says, she “serves as liaison between the characters.” More important, as outsider-interviewer she is the only character in the film with the distance that might make possible an understanding of the moral and emotional confusion in which everyone else is trapped, and who might, as potential identification figure, provide the possibility of such distancing for the audience. Altman’s reaction (and I’m afraid it is a profoundly characteristic one) is to make her as idiotic as he can. The film’s total effect—for all the marvelous local successes—is to engulf the spectator in its movement of disintegration, making intellectual distance impossible. The ironic force of the ending, with the crowd confronting catastrophe by singing “It don’t worry me,” a communal refusal to think, is weakened not simply by the inability to offer any constructive alternative but by a perverse rejection of the possibility. A movie that left Pauline Kael feeling “elated” (“I’ve never before seen a movie I loved in quite this way”) left me feeling somewhat sick and depressed, for all my admiration for its scope and audacity.

The old Hollywood, with its very strong traditional framework of conventions, rules, and expectations, provided many of the necessary conditions wherein minor artists like Tourneur and Borzage could intermittently produce outstanding work. The predicament of Altman (whose best films are scarcely superior to I Walked with a Zombie or Out of the Past—though to me that is sufficiently high praise) strikes me as that of the minor artist forced by circumstances into a position where he must be a major artist, a self-sufficient genius, the “star” director: after Nashville, everyone is going to be looking for the next masterpiece. Those who can resist the very strong pulls of fashionability will watch his development with great interest and great anxiety.

POSTSCRIPT

This essay was written in 1975, during a transitional period in my work. There are things in it I would not say now, or would say differently: I am not happy with the description of Aldrich and Fuller as “emotional barbarians” (at least without careful qualification), and I regret the disparaging reference to the “revolutionary critical fraternity,” to which I now aspire to belong. But I said them, and would not care now to pretend I didn’t (I am opposed on principle to the rewriting of work one has in some respects passed beyond in order to conceal formerly held views). The essay is included here because it is central to the development of this book’s thematic concerns, and because I see no reason whatever to retract or substantially modify its argument: the account of Altman I offered ten years ago has received nothing but repeated confirmation from his subsequent work.

Hence, I see no point in discussing that work in detail: the diagnosis stands, and the prognosis is scarcely more favorable now than it was in 1975. The M.A.S.H./lmages opposition is reproduced in the relationship of A Wedding (1978) to Three Women (1977). The former is, in its smug superiority to and contempt for its characters and in its unquestioning assumption of the audience’s complicity, one of Altman’s most unwatchable and embarrassing films. Three Women expresses a similar contempt, adding to it “European” pretensions of Significance, the model this time being Persona. The thesis that women conditioned by our culture, however seemingly independent, might not be able to escape entrapment in familial roles and structures is not unpromising (though perhaps hazardous for a man to propose). Unfortunately, Altman is totally unequipped to analyze cultural conditioning; the women emerge as victims, yes, but primarily of their own innate stupidity. Quintet, with its mean distinction, has its importance for an auteurist reading of Altman, as it presents his view of human existence in its most naked and schematic form: life as one-upmanship.

Only one of the later films transcends the oppressive limitations of Altman’s insistently reiterated “view”—Come Back to the Five-and-Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean. The success of the film (arguably, after McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Altman’s finest) depends upon a complex of factors inherent in the material. On the one hand its affinity with Altman’s recurrent preoccupations is sufficient to ensure his wholehearted involvement in the project: the play is about women and, specifically, their suffering and humiliation (significantly, the only redeeming scene in A Wedding, the one crack in the Smart-ass armature, was centered on Nina van Pallandt and the agony of drug addiction); much of its action takes the form of games of one-upmanship. But here, the “three women,” unlike their predecessors, are placed firmly within a defined and realized social context, their various humiliations seen in relation to the pressures of patriarchal (or heterosexual male) domination and oppression. Further, through the successive revelations of terrible secrets and exposures of the women’s pretenses and pretensions, they are permitted to reach both self-awareness and mutual supportiveness and acceptance, however qualified.

Obviously, Altman’s identification with a female (never feminist) position is extremely problematic: it is limited almost exclusively to the notion of woman-asvictim, to sensations of pain, humiliation and breakdown. If one reads it as the expression of Altman’s own “femininity,” then it is centered upon masochism and self-punishment; if one reads it as an effort to understand how actual women within patriarchal culture feel, then the masochism begins to look suspiciously like its counterpart, sadism. What is especially interesting about Come Back to the Five-and-Dime is the connection it makes between the oppression of women and patriarchy’s dread of sexual deviation and gender ambiguity. Joe (the only male character to appear in the film, in flashback) is clearly (and sympathetically) presented as feminine (as opposed to the stereotypically effeminate), woman-identified, and gay; as Don Short has perceptively shown,2 the film implies that he has become a transsexual (superbly played by Karen Black—but all the performances are extraordinary) because his society had no place for a gay male. Joanne, having seen more of the world, regrets her sex change; from there, the film goes on to establish her sense of solidarity with the other women, only Mona (Sandy Dennis), as the one least able to relinquish her compensatory fantasies, expressing an insurmountable resistance.

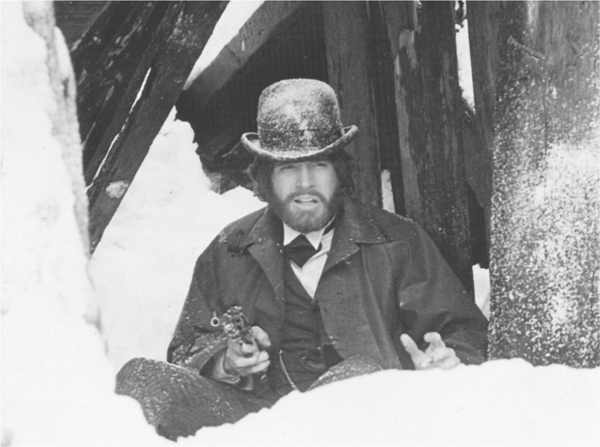

Altman’s Loser-Heroes

Paul Newman in Quintet

Warren Beatty in McCabe and Mrs. Miller

The ending (the final credits, as the camera moves over the now empty and derelict store) remains unresolvably ambiguous: it can be read either as a symbolic gesture of despair (“This is all it amounted to, anyway”) or as a statement that, having learned to understand themselves, their oppression, and each other, the women have been able to leave their prison and move on. People I have consulted tend categorically to affirm one or the other reading as “correct,” those favoring the former alternative being, in general, those more familiar with Altman’s work. But I don’t think anything within the film compels one to accept the auteur-consistent reading; indeed, the second alternative follows more logically from the progress of the action.

Altman’s other recent piece of filmed theater, Streamers (intended, presumably, as an all-male counterpart to Come Back to the Five-and-Dime) is far more confused and problematic. It is also far more hysterical, and it is debatable whether the hysteria resides in the material or in Altman’s response to it. In any case, the parallels between the oppression of blacks and the oppression of gays are much less resonant than those between the oppression of gays and the oppression of women. However, it is clear that the new-found interest in sex- and gender-ambiguity is (as in, on a higher level of achievement, the recent work of Ingmar Bergman—see From the Life of the Marionettes and the Ishmael sequence of Fanny and Alexander) the most promising sign in Altman’s work of profitable new development.

1. Richard Lippe has drawn my attention to the very striking anticipation of this in the scene of James Mason’s suicide in Cukor’s 1954 version of A Star Is Born.

2. In an article that remains unpublished at time of writing.