COHERENCE / INCOHERENCE

All traditional art (and for that matter most avant-garde art) has as its goal the ordering of experience, the striving for coherence; yet all art reveals, if one pursues the matter relentlessly enough, areas or levels of incoherence. Let us consider the coherence first. The drive to understand and, by understanding, to dominate experience must always represent one of the deepest human needs. (This does not necessarily involve dominating other people but rather managing to control one’s experience of them—though one of the recurrent drives in Western art has been domination through objectification and the denial of otherness, a tendency greatly encouraged by bourgeois capitalism with its emphasis on possession.) The artist’s perception of experience may be that it is incoherent, chaotic, absurd, meaningless; he may, alternatively, be battling against what he perceives as false experience (enslavement by the illusory order of the dominant ideology) and may deliberately produce texts that are fractured and fragmentary. In such cases the fragmentation—the consciously motivated incoherence—becomes a structuring principle, resulting in works that reveal themselves as perfectly coherent once one has mastered their rules. The dividing line between coherent works that register incoherence and works that are incoherent within themselves may not always be clear; furthermore, they may well be produced by the same set of cultural conditions.

I want to make it clear from the outset that in referring to “incoherent texts” I am not proposing to discuss (again) Weekend and Wind from the East, films which become as coherent as any when one grasps their mode of functioning. Rather, I am concerned with films that don’t wish to be, or to appear, incoherent but are so nonetheless, works in which the drive toward the ordering of experience has been visibly defeated. I am not, therefore, going to argue that Taxi Driver, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, and Cruising are great works, merely that they are very interesting ones, and that their interest lies partly in their incoherence. The “partly” is important: there are countless movies floating around which are incoherent because totally inept. The three films I have chosen all seem to me to achieve a certain level of distinction, to have a discernible intelligence (or intelligences) at work in them and to exhibit a high degree of involvement on the part of their makers. They are neither successful nor negligible. It is also of their nature that if they were more successful (at least in realizing what are generally perceived to be their conscious projects), they would be proportionately less interesting. Ultimately, they are works that do not know what they want to say.

The reason why any work of art will reveal—somewhere—areas or levels of incoherence is that so many things feed into it which are beyond the artist’s conscious control—not only his personal unconscious (the possible presence of which even the most traditional criticism has been ready to acknowledge), but the cultural assumptions of his society. Those cultural assumptions themselves have a long history (from the immediate social-political realities back through the entire history of humanity) and will themselves contain, with difficulty, accumulated strains, tensions, and contradictions. Relevant here is Freud’s scarcely disputable contention that civilization is built on repression, which accounts for the fundamental dualism of all art: the urge to reaffirm and justify that repression, and the urge of rebellion, the desire to subvert, combat, overthrow. Further, Marcuse, following Freud, has suggested that repression itself operates on two levels: basic repression (universal, necessary to any form of civilization) and surplus repression (specific to each culture, varying enormously in degree from one culture to another), the two levels being continuous and interactive rather than discrete. The revolt against repression may then be valid or invalid, a legitimate protest against specific oppressions or a useless protest against the conditions necessary for society to exist at all, the two not being easily or cleanly distinguishable.

One can say that in periods, usually those designated Classical, when the artist is at one with at least the finest values of his culture—able, like Alexander Pope and Jane Austen, to criticize society for falling short of a set of commonly understood and approved moral codes—the degree of incoherence is likely to be lowest; though one might alternatively argue that in such periods it is simply most deeply buried. There is also the phenomenon of Mozart’s music (created at the precise point of poise or transition between the Classical and the Romantic), which remains for me emblematic of what the ideal Marcusean civilization might be like: art in which work becomes play, in which everything is eroticized, in which freedom and order are proved, after all, perfectly compatible.

CLASSICAL HOLLYWOOD

It would be foolish to imply any strict correlation between Classicism and repression, Romanticism and liberation; nature, after all, has its own order, without which it couldn’t exist, and, at the other extreme, Fascism (the most artificial and repressive imposition of order) is the logical extension of a certain kind of Romanticism. The available theoretical polarities, however, can help give some definition to the way in which the “Classical” Hollywood cinema deserves its title—a Classicism as far as possible removed from anything one might call Mozartian. The American cinema has always celebrated energy, a tendency one normally associates with the Romantic; the energy, however, can only be celebrated when it has undergone a very thorough process of repression, revision, sublimation, displacement. The Classicism of Hollywood was always to a great degree artificially imposed and repressive, the forcing of often extremely recalcitrant drives into the mold of a dominant ideology typified at its simplest and crudest, but most clarified and regulated, by the Hays Office Code. The need for the code (negatively denouncing sexuality in all but its most patriarchally orthodox, procreative form—and displays of it even then—positively upholding marriage, the family, and the status quo) testifies eloquently, of course, to the strength and persistence of the forces it was designed to check: its requirements, passively accepted by studios and audiences, corresponded neither to the films people wanted to make nor to the films people wanted to see. Insofar as Classicism stands for control and Romanticism for release, the Hollywood cinema expresses in virtually all its products, but with widely varying emphases, the most extraordinary tension between the Classical and the Romantic that can be imagined. No wonder that the analysis of Classical Hollywood movies in recent years has laid the primary stress on “contradictions,” “gaps,” “strains,” “dislocations.”

Readers scarcely need to have recapitulated for them the story of what happened to Hollywood in the 50s and 60s—the process that was well under way when Movie first appeared to celebrate a cinema that was already disappearing: television came, the Hays code went, and the studio/star/genre system partly disintegrated. The containing framework of Hollywood Classicism largely ceased to exist. The films made by John Ford after The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, by Howard Hawks after Hatari!, and by Alfred Hitchcock after Marnie all have interest (a few, like Seven Women and Red Line 7000, a very special interest), but they have in common a loss of authority and confidence, an uncertainty as to the tone they wish to adopt. By the mid 60s, the circumstances that had made possible (in Liberty Valance, in Rio Bravo, in Psycho) the transmutation of ideological conflict, such as necessarily exists in any Hollywood movie, into a significantly realized thematic no longer existed.

THE 70s

Although Classical Hollywood had already been dealt a series of death-blows, it might have taken a much longer time dying had it not been for the major eruptions in American culture from the mid-60s and into the 70s: overwhelmingly, of course, Vietnam, but subsequently Watergate, and part counterpoint, part consequence, the growing force and cogency of radical protest and liberation movements—black militancy, feminism, gay liberation.

There are two keys to understanding the development of the Hollywood cinema in the 70s: the impingement of Vietnam on the national consciousness and the unconscious, and the astonishing evolution of the horror film. One must avoid any simple suggestion of cause-and-effect—the modern American horror film evolves out of Psycho; feminism and gay liberation were not products of the war; the history of black militancy extends back for generations. What one can attribute to Vietnam is the sudden confidence and assertiveness of these movements, as if they could suddenly believe, not merely in the rightness of their causes, but in the possibility of their realization. The obvious monstrousness of the war definitively undermined the credibility of “the system”—the system that had hitherto retained sufficiently daunting authority and impressiveness to withstand the theoretical onslaughts of Marx and Freud, the province only of dubious intellectuals. Protest became popular, the essential precondition to valid revolution.

Psychically, the consequences of this reached out far beyond outrage at an unjust war. The questioning of authority spread logically to a questioning of the entire social structure that validated it, and ultimately to patriarchy itself: social institutions, the family, the symbolic figure of the Father in all its manifestations, the Father interiorized as superego. The possibility suddenly opened up that the whole world might have to be recreated.

Yet this generalized crisis in ideological confidence never issued in revolution. No coherent social/economic program emerged, the taboo on socialism remaining virtually unshaken. Society appeared to be in a state of advanced disintegration, yet there was no serious possibility of the emergence of a coherent and comprehensive alternative. This quandary—habitually rendered, of course, in terms of personal drama and individual interaction, and not necessarily consciously registered—can be felt to underlie most of the important American films of the late 60s and 70s. It is central to the three I am discussing here, largely accounting for their richness, their confusion, and their ultimate nihilism. Here, incoherence is no longer hidden and esoteric: the films seem to crack open before our eyes. Among the most obvious manifestations of this are the notoriously problematic endings of both Taxi Driver and Cruising. In the former, there seems to be little agreement as to the attitude and tone of the final sequence—as to what the film is trying to say, conclusively, about its protagonist; in the latter, the uncertainty rises up to the surface of the narrative—the film’s relative commercial failure seems partly attributable to audiences’ exasperated bewilderment over who has done what.

I discuss the significance of the horror film in the 70s at length in the next chapter. Here I simply signal the fact of the infiltration of its major themes and motifs into every area of 70s cinema. All three films discussed here could be regarded, without undue distortion, as horror movies, taking up the genre’s major preoccupations: the monster-as-human-psychopath, who is a product of “normality” (Taxi Driver); the notion of descent-into-hell (Looking for Mr. Goodbar); the doppelgänger, about which Cruising is obsessive to the point of delirium.

TAXI DRIVER

Central to the incoherence of Taxi Driver is a relatively clear-cut conflict of auteurs, though one should not be blinded by this to the ideological conflicts that underlie, and are to some extent dramatized in, the Scorsese/Schrader collision.

Martin Scorsese, with his Catholic Italian immigrant background, his fascination with the Hollywood tradition, and his comparatively open responsiveness to contemporary issues, seems to me a difficult figure to characterize simply; his future development is not easy to prophesy. His films operate within a liberal humanist tradition whose boundaries and limitations remain only hazily defined. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore seems to me in crucial respects a more challenging movie, as well as being altogether richer and more complexly pleasurable, than An Unmarried Woman (whose structure it anticipated in some detail). New York, New York is, as Godard recently observed, “un vrai film” about contemporary “rapports” that has been much harmed by being perceived as “un film rétro.”

The position implicit in Paul Schrader’s work, on the other hand, can be quite simply characterized as quasi-Fascist. This may not be immediately obvious when one considers each film individually, but adding them together (including the screenplays directed by others) makes it clear. There is the put-down of unionization (Blue Collar), the put-down of feminism “in the Name of the Father” (Old Boyfriends), the denunciation of alternatives to the Family by defining them in terms of degeneracy and pornography (Hard Core), the implicit denigration of gays (American Gigolo, to which I shall return later), and, crucial in its sinister relation to all this, the glorification of the dehumanized hero as efficient killing-machine (unambiguous in Rolling Thunder, confused—I believe by Scorsese’s presence as director—in Taxi Driver). It is true that this fundamental position is clouded within individual films by the spurious interest in Existentialism and Bressonian spiritual transcendence, and more would need to be said about, particularly, Blue Collar (the least unpleasant of his movies); but I think this defines the essential viciousness of Schrader’s work.

Although some clash of artistic personalities and ideologies lies at the heart of Taxi Driver, I do not see any possibility, even were it desirable, of sorting through the film to assign individual praise and blame. Instead, I offer a series of annotations designed to indicate the major concerns of the film and its unresolved contradictions.

1. The Excremental City Taxi Driver represents the culmination of the obsession with dirt/cleanliness that recurs throughout the history of the American cinema—together, of course, with its metaphorical derivatives, corruption/purity, animalism/spirituality, sexuality/repression. In the vision of Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), which is neither identical with nor clearly distinguishable from the vision of the film, the filth kept at bay through so many generations of movies by the traditional values of monogamy/family/home has risen up and flooded the entire city. Travis becomes obsessed with the mission of washing the scum from the streets—the scum being both literal and human flotsam. The outcome of this obsession is the massacre in the brothel and the rescue of Iris (Jodie Foster) in order to restore her to her parents and a small-town education, the act that establishes Travis as a hero in the eyes of society and the popular press.

2. The Angel Luther saw heaven while sitting on the lavatory. Travis’ vision is of Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) as an “angel” floating above the excrement of the city. The film progressively exposes (for Travis—it is always obvious enough to the viewer and might be argued to be implicit in the casting) the illusoriness of this: she is an ideological construct, a figure of almost total vacuity whose only discernible character trait is opportunism. The imagery of the last scene enacts all this beautifully, reducing her to a disembodied head floating in Travis’ rearview mirror.

3. The Commune in Vermont The city is filth, the angel an illusion; what is left? During Travis’ conversation with Iris, he asks her if there is anywhere she wants to go to escape the squalor of her current existence as a thirteen-year-old prostitute. She replies tentatively that she has heard about “a commune in Vermont.” This, mentioned in passing, given no concrete realization, parallel or further reference anywhere in the film, is the nearest it ever comes to proposing a constructive alternative, a life that might resolve the dirt/repression quandary. Travis dismisses it immediately: he once saw a picture of a commune in a magazine and it “didn’t look clean.”

4. The “Scar” Scene The relationship of Taxi Driver (and Hard Core) to The Searchers has been widely recognized. Scorsese and Schrader were fully aware of it and refer to the brief scene between Iris and her pimp/lover Sport (Harvey Keitel) as the “Scar” scene—the equivalent of a “missing” (and arguably essential) scene in The Searchers defining Debbie’s relationship to Scar and Comanche life. It is a scene Ford could not conceivably have filmed, and Scorsese and Schrader are quite right in implying (I presume) that its absence definitively highlights the cheating, evasion, and confusion that characterize the last third of his film (itself an archetypal incoherent text). It is certainly to their credit that the “Scar” scene exists in Taxi Driver (significantly, it is the only substantial sequence that takes place beyond Travis’ consciousness); it is less certain that it represents any sort of valid equivalent (to equate life with the Comanches to life in a brothel may strike one as dubious on several counts) or that its existence helps clarify what the film is saying. It provides the movie with its solitary moment of tenderness, suggesting that Sport loves Iris as well as exploiting her, hence by implication opening up the question of what exactly “love” might be, beyond the societal norms of Travis’ romantic idealization of Betsy and Iris’ parents’ concern for her. Already in The Searchers, the ideological weight of the notion of “home” was pretty thoroughly undermined, but it retained sufficient force for the “happy ending” of Debbie’s return (supported by the film’s suppressions and distortions) to come across as slightly more than a mockery. In Taxi Driver, “home” is reduced to a photograph on a wall and a letter read aloud on the sound track. The function of the “Scar” scene seems to be, in opposition to this, to call into question any easy assumption we might have that anything would be preferable (for a thirteen-year-old girl) to prostitution: with Sport, Iris shares an equivocal tenderness, whereas there is no indication that “home” offers her anything at all.

5. The Hero As with The Searchers, the central incoherence of Taxi Driver lies in the failure to establish a consistent, and adequately rigorous, attitude to the protagonist. We can see the film in relation to both the western and the horror film. With the former, Travis is the gunfighter-hero whose traditional function has always been to clean up the town; with the latter, he is the psychopath-monster produced by an indefensible society. The latter option appears fairly unambiguously dominant through most of the film, but the former is never totally eclipsed. The film cannot believe in the traditional figure of the charismatic individualist hero, but it also cannot relinquish it, because it has nothing to put in its place. Travis’ behavior is presented as increasingly pathological (culminating in his acquisition of a Mohawk Indian haircut), with his ambitions increasingly monstrous (the assassination of a politician no worse than most) and his achievements useless, unless one has an automatic commitment to the family (the city will go on as before, excremental as ever). Yet the film can neither clearly reject him (he remains, somehow, The Hero, like Ethan Edwards) nor structure a complex but coherent attitude to him (such as Cimino partially achieves in The Deerhunter).

6. Chingachgook Meets Geronimo A tantalizing addendum to this is provided by the fascinating confrontation between Travis (his head shaved like a Mohawk) and Sport (with the long hair and head-band of an Apache). No moment in the American cinema dramatizes more succinctly the famous fundamental ambivalence in the American attitude to the Virgin Land (Garden of Eden/Savage Wilderness) and the Indian (Noble Savage/Ignoble Heathen Devil). Further, the Mohawk is traditionally associated with the cleanness of forests and lakes, the Apache with the dirt of the prairie. Yet what the scene ultimately testifies to is the Hollywood cinema’s (America’s) continuing inability to resolve its dichotomies. The Mohawk/Apache, Garden/Wilderness opposition becomes (within the context of the Excremental City) a sterile dialectic that appears at once archaic and unresolvable, the image of the Noble Savage reduced to the rhetorical gesture of a psychopath, the revolutionary rage of the Ignoble Savage to the attempted self-vindication of a pimp.

7. The Ending No one is likely to suggest that the ending of the film (the scenes following the point where most people, at first viewing, expect it to end—the massacre and Travis’ finger-to-forehead gesture of mock suicide) can be read quite unironically, yet the irony seems curiously unfocused, its aim uncertain (the ending of Fort Apache offers a very close parallel). The effect is of a kind of paralysis. Being unable to achieve any clear, definitive statement about the hero, either as individual character or, beyond that, as the dominant mythic figure of patriarchal culture, the film retreats into enigma. Travis becomes a public hero (ironic), feels satisfaction at what he has done for Iris and her parents (arguably ironic), and reaches some personal serenity and satisfaction with himself (doubtfully ironic); he is now able to see through and reject his angel, and, mission accomplished, retreats into the streets rather as Ethan Edwards retreats into the wilderness. Rather like but not quite like, as Ethan is going nowhere and Travis is back in the heart of the Excremental City. The individual spectator can think (according to personal predilection) either that the hero will continue to cleanse the city of its filth, or that the psychopath-monster will explode again in another useless bloodbath. There is a third alternative, which comes closest to rendering the action and images intelligible—the notion that Travis, while achieving nothing for an obviously beyond-help society, has achieved through his actions some kind of personal grace or existential self-definition, and that this is really all that matters, since civilization is demonstrably unredeemable. This is very Schrader (American Gigolo moves to an identical conclusion) and not at all Scorsese. I find it morally indefensible, pernicious, and irresponsible: it implies that one’s existential self-definition can validly be bought at the cost of no matter what other human beings. It also represents a debased and simplistic (again, quasi-Fascist) version of Existentialism, restricting it to a matter of the Chosen Superior Individual and depriving it of all social force. It could only work in the film (as it does, if “work” just means “make sense,” in the spiritually and emotionally poverty-stricken American Gigolo) if the audience were identified with a single ego and all the other characters reduced to puppet-like subordination. It seems to me that at the end of Taxi Driver we are (thanks to Scorsese and Jodie Foster) more concerned about Iris than about Travis, who has long since moved outside the bounds of any reasonable human sympathy or identification.

LOOKING FOR MR. GOODBAR

Looking for Mr. Goodbar has been widely perceived as an ultra right-wing, reactionary movie. Liberals were quick to heap abuse on it; some feminists saw it as an assault on women’s liberation and as tending to encourage violence against women; gay activists saw it as strengthening the popular myth that associates homosexuality with neurosis. A Canadian minister wrote a eulogy of the film as a Lesson to Us All, claiming it to be an account of its heroine’s descent into Hell (her face disappearing into blackness at the end) as rightful punishment for promiscuity and a neglect of the Good Old Values. I am not going to argue that these responses are totally misguided or that they answer to nothing in the film; in terms of immediate general impression, they are probably partly correct. But they are certainly very partial, leaving out of account many elements and implications that would qualify and contradict them.

1. The theme of descent—or progressive dissolution—is certainly strong in the movie, signaled especially by the care Richard Brooks has taken, from sequence to sequence, to trace the deterioration of Teresa’s apartment. Yet it is highly questionable whether the tone is moralistic, at least so far as Teresa (Diane Keaton) is concerned, and whether the notion of self-righteous satisfaction at watching a woman receive just punishment for sexual freedom, drug-taking, and rebellion against traditional values sufficiently (or even at all) accounts for our experience of the movie. For one thing, the punishment (even if we are thorough-going puritans) isn’t just: like Marion Crane in Psycho, Teresa has firmly decided to reform her life just before she is killed; she picks up her murderer, not because she wants sex, but as a means of deflecting the attentions of an unwanted but persistent suitor. More important, however, are matters of casting and identification. Keaton (with Brooks’ obvious encouragement—there are no signs of a clash of intentions between director and star) brings an infectious zest and vitality to the role; though her sexual experiences are not presented as deeply satisfying, they retain a sense of enjoyment, resilience, and sheer fun. I find no suggestion in the scenes in singles bars, for example, that we are supposed to be shocked.

The question of identification is obviously very complicated, with the constant possibility of the intrusion of personal bias (my own experiences have at certain periods of my life been very close to Teresa’s—short, so far, of getting murdered—and I have always felt grateful to the film for reflecting them in what strikes me as a very unpuritanical way). Much valuable work has been done by feminists, such as John Berger and Laura Mulvey, on the objectification of women in Western culture and the resulting position (ownership, domination) of the (by implication) male spectator. But some of this work (e.g., Mulvey on Sternberg) can lead to dangerous over-simplification, by failing to take into account either the complexity of narrative structures or the large areas of experience—and ways of experiencing—common to both sexes. Virtually all of Goodbar is given us via Teresa’s consciousness; the fantasy sequences allow us privileged access to her mind, a dimension denied the male characters (it is they, here, whom we look at, from Teresa’s viewpoint). The characterization and the narrative procedures combine to transcend any sexual division in identification. I doubt very much whether any man (short of an advanced sadist) simply takes pleasure in the violence inflicted on Teresa at the end; he is far more likely to empathize with her terror.

2. The descent-into-hell structure would depend, for its validity and effectiveness, on the presence within the film of a realized concept of the “normal” as yardstick, and this simply does not exist. The characters who might embody a traditional normality are consistently undermined. The university professor (Teresa’s first great love) cheats on his wife and exploits his female students for sex; the unity and solidarity of Teresa’s own family is shown as a desperate and repressive illusion sustained by the father, and depends on a refusal to recognize unpleasant truths (in the nostalgically venerated past as well as the “decadent” present). Patriarchal authority is nowhere endorsed as providing adequate judgment on Teresa’s life.

Crucial here is the most significant change Brooks made from Judith Rossner’s novel—the transformation of the character of James, the lawyer in the novel, who becomes the film’s social worker (William Atherton). In the book, James does represent a possible “normality,” a settled and stable life, which Teresa could theoretically choose; he doesn’t excite her (especially sexually), but he is safe, reliable, and loving, everything a good girl is supposed to need. The film makes him just as neurotic and potentially dangerous as everyone else. Teresa’s murder is, in fact, anticipated in two key scenes that set up both her suitors as potential killers: Tony’s (Richard Gere) dance with the phallic, luminous switchblade (where Teresa thinks he is going to attack her), and James’s story (which he later tells her was a fantasy, thereby increasing rather than diminishing its sinister application to himself) about how his father beat his mother into a bloody pulp when she laughed at him for being impotent (precisely the reason Teresa is killed—though the laughter is only in the killer’s mind). The points established seem to be that “normality” is an ideological construct, not a reality; that violence is inherent in sexual relationships under patriarchy; and that it doesn’t ultimately matter who kills Teresa—any of the men in her life could have, and the killing arises more out of a cultural situation than individual responsibility. All three points strikingly anticipate Cruising.

3. Other changes and emphases in Brooks’ adaptation of the novel, however, push the film in exactly the opposite direction.

He places far more emphasis than Rossner on Teresa’s work, changing its nature and idealizing it as the “positive” side of her life. In the book, she is just a schoolteacher, and not much is made of it; in the film, she teaches deaf children. The change allows Brooks to give Teresa’s work incontrovertible value, while at the same time enabling him to evade (and the audience to forget) the fact that the children will grow up in the same world that confuses and finally destroys Teresa. We never think of them as inheriting her moral and emotional problems, because they have to cope with a highly specific, practical one; Teresa is helping them lead a normal life in a sense that gives a very limited definition to the word. The scene in which the children express violent resentment at Teresa for arriving late one day seems to me both implausible (they don’t even wait to find out whether she is ill or has been in an accident) and overstated: it depends purely on the audience’s knowledge that she has overslept after taking drugs, and exists exclusively to add to our sense of her guilt and degeneration.

Brooks also strongly underlines the probability that Teresa’s childhood disease is hereditary, and thus seriously weakens and confuses the film. He seems to want to say that Teresa is representative of the problems, disturbances and confusions of stepping outside a stable social/moral structure; that such a move is, however, legitimate; that in any case the stable order (if it ever was stable) has crumbled, and was always repressive. This would involve him in defending the right of physically and psychologically healthy women to express their sexuality with any partners they wish. He can’t quite do this (though he comes surprisingly close), so he has to say that Teresa is a special case, crippled, unable to bear children for fear of passing on a hereditary disease. Her sexual freedom can now be explained, implicitly, as the result of her being excluded from a normal life: the explanation has to remain implicit (though very close to the surface), because the concept of normality is clearly rejected by the film.

4. This confusion (evasion?) is paralleled in the presentation of the film’s gay characters. If one had only the closing scene to deal with, it could be argued that the treatment of gayness is both intelligent and enlightened. Brooks makes it clear that the young man murders Teresa, not because he is gay, but because he can’t accept that he is gay: instead of associating homosexuality with neurosis, the film here associates self-oppression with neurosis, an entirely different matter. There is another significant change here from the novel: in the book, the murderer is not really gay, but at most bisexual (he has been exploiting a gay man in order to be fed and housed in a strange city); his pregnant wife is given the verification of documentary third-person narration; he successfully has sex with Teresa. In the film, we assume (having only his word for it) that he is inventing the wife and baby as a way of asserting his “normality” and “manhood”; he kills Teresa because his inability to get an erection with her forces on him the truth about himself. Like Teresa, then, he is the victim of a society that assigns people fixed roles, imposing on them notions of what a real man or real woman should be. One might even obliquely infer from the ending a negative statement of the links between feminism and gay liberation, since the catastrophe arises out of the characters’ failure to grasp them.

Any such reading, however, is offset by the previous treatment of gay characters. The gay bar, though not in itself presented offensively, seems clearly meant to mark a stage in Teresa’s descent; the murderer’s lover is a shamelessly offered stereotype, hysterical, self-hating, sniveling. It’s as if the film wants to say both that homosexuals would be all right if society let them accept themselves and that homosexuals are inherently sick and degenerate.

Of the three films, Goodbar seems to me ultimately the most unreadable, the farthest from resolving—perhaps from recognizing—its contradictions, or organizing them into a significant dialectic.

Cruising

To do some kind of justice to Cruising (it has received none so far),1 it needs to be placed in two contexts: the sudden outcrop of movies either centrally or peripherally concerned with gayness that have emerged at the tail end of the 70s, and the social issues raised by the gay liberation movement, the theoretical program it implies.

“Emerged” may not be quite the word: of the four main relevant films, one has not yet been released and another has already sunk without a trace. Yet the fact that the films got made testifies to some (however muddled and hostile) awareness that the gay movement was somehow there and posed some kind of threat; their existence marks a point where gays can no longer be represented surreptitiously, without overt reference to sexuality, whether as comic-relief interior decorators or shifty-eyed film noir henchmen. And, although it came rather late, I think the recognition of gayness belongs very clearly to the 70s, the reactionary 80s so far marking a happy return to the mindless and clandestine (as in Can’t Stop the Music), as if nothing had happened.2

The chief interest of New York After Midnight (aside from the fact that it was co-scripted by Louisa Rose and that tantalizing thematic echoes of Sisters can be glimpsed among its ruins) lies in its remarkable sociological insight that if a woman goes into a gay disco, the men will immediately stop dancing with each other and try to rape her; as the film may never surface, one need say no more. Windows, in which Elizabeth Ashley believes that, if she pays a man to rape Talia Shire, the latter will instantly be converted to lesbianism and return her unrequited passion, mindlessly reproduces the familiar stereotype of lesbians as sick and predatory. So few people went to see it that its social impact is negligible; one is only sad that an intelligent actress (Elizabeth Ashley) consented to appear in it.

The key film here (Cruising apart) is one in which gayness appears peripheral, the film’s homophobia being so muted as to have passed largely unnoticed (with the honorable exception of Stuart Byron in the Village Voice). Nonetheless, homophobia is central to American Gigolo. It was playing without protest in the same Toronto theater complex where gay activists were picketing Cruising; I find it incomparably the more offensive of the two films, and would argue that its social effect is probably far more harmful, being covert and insidious (in addition to the fact of the film’s trendy commercial success). The entire progress of the protagonist, Julian (Richard Gere), is posited on the simple identification of gayness with degradation. Julian, the gigolo of the title, is accorded the status of Existential Hero because he takes pride in bringing frustrated middle-aged women to orgasm (for suitable monetary compensation). He is trying to forget a past when he used to “trick with fags,” and is threatened with having to return to it, coerced by a black homosexual pimp and criminal. As Julian is not supposed to get pleasure from his sexual experiences with older women but likes to give them pleasure, as well as get paid, the implication is presumably that “fags” don’t even deserve pleasure. The film traces Julian’s progress toward salvation, in the form of a heterosexual relationship, viewed with true Fascist sentimentality (and direct plagiarism from Bresson) as uplifting and redemptive. The fact that the ultimate Schrader villain is both black and homosexual can scarcely be regarded, in the general context of his work, as coincidental.

Hollywood has adopted somewhat different strategies in dealing with, and putting in their patriarchal place, the women’s movement and the gay movement. To an astonishing degree it has managed to ignore both (it never acknowledges them as movements, except derogatively). Its method with feminism has been generously to admit that, yes, a woman has every right to be independent and autonomous, before going on to suggest that she will then be able to use her freedom of choice to commit herself to a burly, bearded patriarch like Kris Kristofferson or Alan Bates. With the gay movement, in the context of a generally homophobic culture, it can safely resort to simple vilification.

In contradistinction to all this, and pointing ahead to a discussion of Cruising, one may briefly suggest the issues one would hope to see acknowledged in a contemporary movie about gayness.

1. The oppression/exploitation of gays in our culture.

2. The repression of bisexuality, a commonplace of psychoanalytical theory. Here, bisexuality is posited as the natural state of the “polymorphously perverse” infant, whose social/ideological construction (fulfilling the accepted norms of masculinity and femininity, a major aspect of “surplus repression” within our culture) involves the systematic denial of its natural homosexual impulses. The failure of this process of socialization results in exclusive homosexuality—which one can therefore logically accept as a perversion, provided this description is accepted of exclusive heterosexuality as well. This gives rise to

3. The acknowledgment that gayness is not a thing apart—that everyone is potentially gay or has potential gay proclivities, and also

4. Homophobia: the irrational hatred of homosexuals. The theory of the repression of bisexuality offers the only plausible explanation of this unfortunate maladjustment: what is repressed is not destroyed but continues to exist in the unconscious as a constant threat; what the homophobe hates is the gay within himself.

5. The assault on patriarchy and the “Law of the Father,” with the heterosexual male as the ideologically privileged figure of our culture.

6. The critique of heterosexual relations under patriarchy (as based on inequality and domination, i.e., the subordination of women): the family, monogamy, romantic love.

7. Attempts to construct new ways of relating, hence, necessarily, new forms of social organization.

8. The need to project strong positive images of gay life to offset the prevalent homophobia.

9. The recognition of gay liberation as a subversive political movement with defined theories, aims and principles.

10. The strong connections between gay liberation and the women’s movement.

Gay activists have demonstrated against Cruising at all stages, attempting to disrupt the filming and attacking it in the gay press. In terms of its probable immediate social impact, they may be quite correct (and in any case the campaign against the film after its release, involving the picketing of cinemas and the distribution of leaflets, is exemplary in suggesting, within a democratic society, a constructive alternative to censorship). Yet Cruising opens up (not necessarily from a positive viewpoint) the first six of the above issues, as I shall show. For the rest, within the international commercial cinema only Ettore Scola’s A Special Day broaches the last, and the other three have yet to be raised or even hinted at. A useful comparison is provided by The Consequence, a German film widely regarded by gay activists as “positive,” which raises only the first of my ten issues and proceeds to labor it far beyond the point of overkill in a tone of whining self-pity, at the same time whole-heartedly reinforcing the good old heterosexual values of romantic monogamy and placing its pair of doomed and idealized gay lovers in a world of heterosexuals characterized as exclusively evil, manipulative and vindictive. I shall argue that the negativity of Cruising offers far more that can be used: that, whatever he may have intended (which remains, to me, largely mysterious), William Friedkin’s film is by far the more radical and subversive of the two.

1. On one level, the incoherence of Cruising is of a different order from that of Taxi Driver and Goodbar: its surface is deliberately fractured, the progress of the narrative obscured, in a way that one must recognize as extremely audacious within the Hollywood context (though not necessarily artistically successful). In one respect, indeed, it presents its narrative as strictly impossible, providing cinematic statements that are not only contradictory but mutually exclusive. I find it very hard to be sure just what Friedkin had in mind here—to judge the level of sophistication on which the film seeks to operate. In style, it is as little “Brechtian” as one can imagine, yet it seems to want its viewers to question the “realist” experience of narrative itself. One can begin at the end:

a. Who committed the last murder (the brutal stabbing of Ted Bailey/Don Scardino, the most sympathetic of all the film’s gay characters)? Friedkin makes it impossible to know, whereas in Gerald Walker’s novel it is perfectly clear. There are strong signals that it may be the protagonist Steve Burns (Al Pacino), the cop who has assumed the identity of the killer he has tracked down, and who is continuing the killer’s destruction of gay men who arouse him sexually (Pacino’s final look in the mirror; Detective Edelson’s very emphasized “Jesus Christ!” when he learns that Burns lived next door to the victim). Yet the film provides no evidence for this assumption, and, indeed, does provide contradictory suggestions that Ted may have been murdered by his lover (last seen brandishing a knife identical to the murder weapon).

b. But: who committed all the other murders? The film culminates in a confrontation and an arrest (played out in meticulous doppelgänger fashion between policeman and suspect). The “killer,” on his hospital bed, denies that he has ever killed anyone. The only legal evidence is his fingerprint on a coin attested to by Edelson, who—though presented as more humane and concerned than most of his colleagues—has been shown to be less than perfect, and who is under great pressure to produce a murderer or lose his job. There is also one indisputable piece of cinematic evidence—but this is precisely where the narrative impossibility comes in. We see the killer, Stuart Richards (Richard Cox), entering the park to talk to his father in a sequence strongly signified as “fantasy” by being overexposed (we learn subsequently that the father had died ten years ago); during this conversation, Friedkin cuts in “memory” flashbacks of the first two killings shown in the film, to which only the murderer could have access. There should be, then, no doubt that Stuart Richards is the killer—except that the killer in the first pick-up/murder scene is very clearly played by a different actor. If a central point in the narrative is proved impossible, then presumably the whole film loses its “realist” intimidation: everything becomes a matter of “if,” “maybe,” “let’s pretend,” rather than “this is what happened.”

c. The film does not suggest that Burns could have been responsible for all the killings, but it clearly links him with more than the last one. After the murder of the clothes designer in the porno peep show, Friedkin cuts directly to Burns arriving home, appearing haggard, disturbed and weary—as if he had just performed the murder. When he confronts his doppelgänger in the park at the climax, he repeats the killer’s ritual baby talk which precedes each murder (obviously a father/child game): “Who’s here? I’m here … ” The only way he could possibly know about this is from the garbled account of the male transvestite who reports it (to another policeman) as something a friend of his overheard—except that the transvestite misquotes it, and Burns gets it right.

The film suggests then: that there are at least two killers and could be several; that we don’t have to feel we know who the killer is, because it could be anyone; and that the violence has to be blamed on the culture, not on the individual. One of the strongest complaints of gay activists has been that the film associates the violence specifically with homosexual culture, and shows both as somehow contagious (“the vampire theory of homosexual contagion” as Robin Hardy says in Body Politic). It is quite possible that this is the overall impression the film makes on general audiences, the imagery of violence and leather bars being so insistent. It is not, however, what the film actually says or certainly not all it says.

2. The near-beginning of Cruising (after a prologue showing the finding of a half-decomposed arm in the river) succinctly takes up the excremental city theme of Taxi Driver and seems to apply it specifically to the homosexual subculture: “They’re all scumbags,” says a cop in a patrol car, introducing a point-of-view shot of a nocturnal street populated exclusively by cruising gays. This simple vision, which presumably typifies the kind of thing against which gay activists were protesting, is very strongly qualified by three facts. First, the cop in question is given unmistakable signifiers (physical appearance, expression, body language, intonation) indicating “This is a very unpleasant, uptight, potentially violent person.” Second, a couple of screen minutes later he is compelling a male transvestite to suck him off. Third, his fellow patrolman has just been indulging in a diatribe against his wife to the tune of “I’ll get that bitch”—the film’s first intimation of violence is established within the context of “normal” heterosexual relationships, with strong connotations of patriarchal domination and brutality, before any gays have appeared.

This introduction concisely states the theme of the interchangeability of the police force and the leather bars—the film’s most comprehensive extension of the doppelgänger motif. When the transvestite protests to Detective Edelson (Paul Sorvino) against his exploitation by the patrolmen, Edelson asks, half cynically, “How did you know they were cops?” It is clearly his way out and establishes his complicity in the film’s exploitation/corruption patterns. Yet, subsequently, the remark is given some ironic force when we are taken inside an S/M bar in which all the clientele are dressed in police uniforms. (The irony becomes particularly convoluted when Burns is accused by the proprietor of being a cop and turned out—because he is out of uniform.) Further, the married cop of the opening (or, given the narrative games Friedkin plays, his double, played by the same actor) turns up twice in the context of the gay subculture, cruising Burns once in a bar (where he is closely juxtaposed with Stuart Richards) and once in Central Park. (He is also in charge of the investigation into the final murder, before Edelson takes over.) The film never explains this: we cannot imagine that in the cruising scenes he is another decoy, because the decoy has to have the physical build and general appearance of Al Pacino. Finally, the grotesque scene in which both Burns and the innocent suspect are beaten up at police headquarters by an immense black policeman dressed only in a cow-boy hat and jockstrap has only the vaguest narrative plausibility, and seems to be there primarily to underline the connection between the two worlds.

All of this certainly affects our reading of the development of Steve Burns into the actual or potential killer of Ted Bailey: yes, he can be seen as brutalized by his experience of the S/M sub-culture, but equally his brutalization can be attributed to the contamination of police work. Both dominant culture and sub-culture are revealed as built on, and hopelessly corrupted by, power relationships.

The two moments in the film where the imagery seems most insistently to link violence with homosexual behavior are both specifically concerned with domination: the murder of the clothes designer in the porno peep show, culminating in blood splashing over the images of homosexual lovemaking on the screen; the increasingly frantic intercutting of Burns drawn into disco-dancing with another man and progressively enjoying it with a) a man being publicly fist-fucked and b) the aloof silent figure of a leather-masked executioner. The film clearly presents pornography (domination through objectification) and public fist-fucking in terms of degradation (a view I feel no great desire to challenge). Whether we are meant to view Burns’ enjoyment of gay disco-dancing in the same light seems to me uncertain. The images can be given that meaning; yet montage carries inherent ambiguities (comparison or contrast?—“attraction” or “collision”?). The alternative is to read the scene, not as an attack on the evils of gay disco-dancing, but as an acknowledgment of the contamination of everything in our culture (even a pleasurable dance) by the domination/subjection drive. If Burns at the end of the film has taken over the identity of homophobic killer, then this scene (the arousal in him of homosexual desire) becomes crucial.

3. The film presents no positive images of gay culture, but then it offers no positive alternatives of any kind to the corrupt and disintegrating society it depicts—certainly not a return to any possible traditional “normality,” which (insofar as it is even hinted at) takes the form of a cop saying of his wife “I’ll get that bitch.” A film depicting the warmth, generosity and openness I have found in gay life—qualities vitally connected to sexual freedom, to the partial undermining within gay culture of the possession/domination/submission syndrome—has yet to be made. Only the admission to the film of some such dimension could have resolved Cruising’s knot of contradictions. In its absence, one should note two (admittedly subordinate) aspects that somewhat mitigate the overall suggestion of the leather sub-culture as the epitome of a domination-and-violence, inherently sadomasochistic culture. One is that, with the exception of Ted Bailey’s lover, all the individual gay characters (the suspect and the victims, including Ted himself) are presented quite sympathetically, with no sense that we are meant to be shocked at their sexual orientation. (The novel from which the movie was adapted, on the other hand, can scarcely contain its disgust for homosexuals; its thesis that the only thing more loathsome than a homosexual is a person who hates homosexuals involves its author in quite inextricable knots.) The other arises from Friedkin’s use of gay extras in the bar scenes in the pursuit of authenticity, many of whom look irrepressibly happy and energetic, especially in contrast to the haggard face of Al Pacino: we may ask ourselves how, if this is hell, so many people appear to be enjoying themselves in it.

4. The issue of homophobia is at the thematic heart of the film, in its revelation of the reasons why the murders are being committed. If its narrative obscurities have the effect of removing blame from any individual killer, this is to define it the more clearly on the thematic level. Stuart Richards is told (believes he is told) to commit the murders by a father who would otherwise despise him: the killings are his way of proving himself the “man” his father wanted him to be. By killing gays, that is, he is symbolically destroying the gay within himself “in the Name of the Father”—a long-dead father interiorized as superego. Taking Stuart as the killer throughout (which the film both asserts and denies), one can trace a logical progression through the murders: the first victim we know of was Stuart’s Columbia University professor (psychologically a particular aggravation in combining father figure and sexual object/seducer); the second is the actor (the first murder shown in the film), the only victim with whom we know the killer had intercourse; from there on, presumably, arousal without performance is enough to trigger off the mechanism. Further, all the victims (plus Burns, plus various extras, including an Al Pacino clone who turns up a couple of times in the bar scenes) are Stuart’s doubles—i.e., the tangible embodiments of his repressed gay self: the killings are the projection of an internal violence directed against himself. Somewhat explicitly but more by implication, the film’s real villain is revealed as patriarchal domination, the “Law of the Father” that demands the rigid structuring of the subject and the repression of all conflicting or superfluous realities—the denial of the Other, both internal and external. The implications of this are enormous: taken symbolically, it was Stuart’s father who demanded the Vietnam war. His demands (and their impossibility) are enacted in the brutality and corruption of the police, and parodied in the sadomasochism of the leather bars. It is a remarkable paradox that a film almost universally perceived as antigay should produce at its center one of the fundamental social/psychoanalytic insights on which the case for gay liberation rests. (For an unambiguously antigay movie, compare the Dutch Dear Boys, by Paul de Lussanet, which presents all its gay characters as mean-spirited predators.)

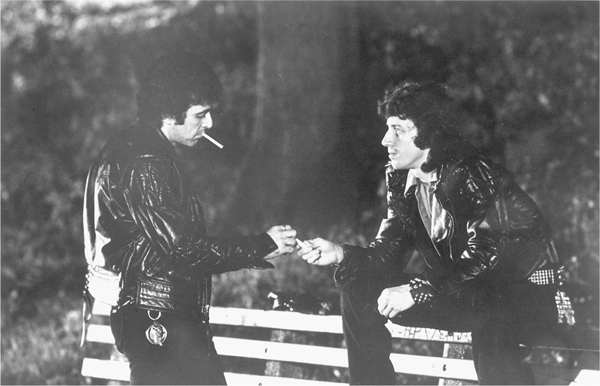

Doubles in Cruising

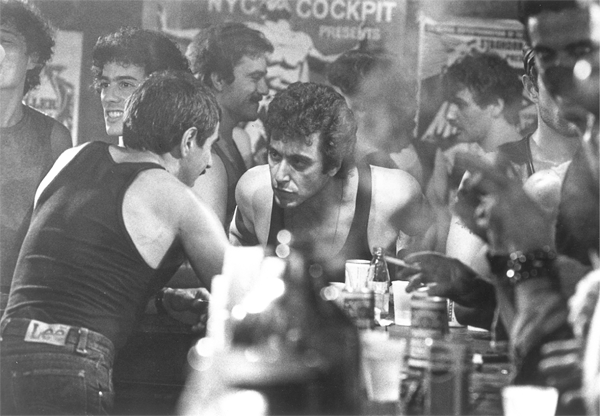

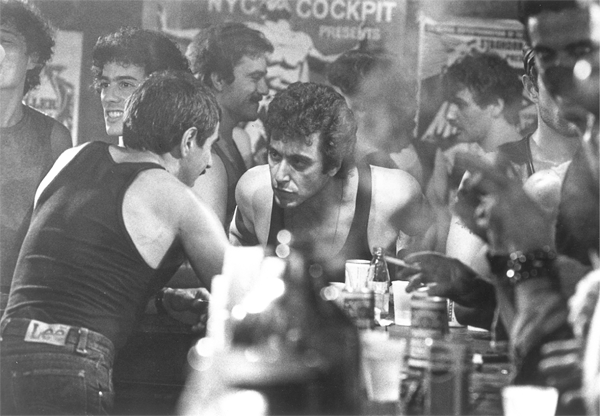

Al Pacino in a gay bar

Al Pacino and Richard Cox

5. It remains to consider the development of the Pacino character, his relationship with his lover Nancy (Karen Allen), and the film’s extremely enigmatic ending. It is here that Cruising seems at its most tentative and evasive: uncertain what it wants to say (what it dare say?), it moves into a kind of paralyzed neutrality. To start almost at the end, if we assume that Burns has murdered Ted Bailey, the only possible motivation is an extension of the previous killer’s homophobia. The film seems deliberately evasive as to whether Burns actually has sex with men in the pursuit of his duties, but it is clear that his confidence in his heterosexuality becomes progressively undermined, and the possibility that a sexual relationship with Bailey might develop is strongly suggested: he murders Bailey because he is sexually aroused by him. Looking back from that, we can trace the undermining of his patriarchal sexual identity, his involvement in the sub-culture systematically counterpointed with scenes showing the deterioration of his relationship with Nancy, his lovemaking vacillating between (compensatory or sadistic?) aggression and passivity. Part of the problem in reading the film is that the relationship is given no clear definition at the outset; it certainly carries no positive charge, both characters seeming physically pallid and drained of energy (energy fills the leather “underworld”). Nancy, until the end of the film, remains a colorless, neutral figure with no defined position beyond that of offering Burns ineffectual support.

How to read their final scene? Burns, the assignment officially over (but with Bailey’s unsolved murder in the immediate background), has asked to come back to her, and is shaving in her bathroom (symbolically cleansing himself?); he nicks his throat; his face continues to look haggard and disturbed. Meanwhile, Nancy finds the SS uniform he has worn in leather bars discarded on a chair, and automatically puts it on. Cut back to Burns’ face in the mirror. We (and he) hear the clinking of metal approaching the bathroom door. Slow dissolve from his face to the river and tug-boats—has the film come full circle to its opening images, implying the finding of another corpse or severed limb? One can read this in two ways (again, playing the film’s game of “perhaps”): Burns, now irremediably disturbed, is about to murder Nancy when he sees her dressed in leather; her body will be found in the river. Or, less specifically, though one murderer has been caught, this resolves nothing; while the culture continues as it is, the patterns of violence will continue, spreading everywhere. What is interesting is that it is Nancy who dons the uniform: the “contagion” theory becomes strained to breaking point if we have to assume that she has now contracted the “disease” from Burns. Rather, it seems logical to take the ending as answering the cop’s words about his wife at the beginning. It then becomes a reminder that sadomasochism, far from being the preserve of leather-clad-homosexuals, pervades the entire culture and is inherent in its fundamental relationship patterns (parent-child, husband-wife), all of which are centered on domination/submission: Nancy is simply reversing the traditional male/female role and becoming the dominator.

One could certainly accuse Friedkin of not having grasped the positive, radical implications of gay liberation (but how could he, given the overwhelming suppression of gay voices within the dominant culture?): he uses gay culture to epitomize domination relationships, whereas at its best it transcends them. (Even gay S/M seems usually to carry strong connotations of play and parody—i.e., it turns the domination/submission patterns of traditional relationships into a game, with the roles often interchangeable.) He hasn’t fully confronted the fact that the central inequality of our culture is male/female, and that same-sex relationships offer at least the possibility of escaping this. Yet the confusion of Cruising seems to me infinitely preferable to the self-indulgent romanticism of The Consequence or the gay self-contempt of Dear Boys.

CONCLUSION

What, finally, do I wish to assert about these films?

First, that they offer more complex experiences than have generally been recognized: they have occasioned me a great deal of pleasure and disturbance, in roughly equal measure.

Second, that the only way in which the incoherence of these movies (the result, every time, of a blockage of thought) could be resolved would be through the adoption of a radical attitude: in Taxi Driver, the consistent critique of the patriarchal hero; in Goodbar, a commitment to feminism; in Cruising, to gay liberation; in all three, a commitment to social/sexual revolution. No possibility of this yet exists within the Hollywood context: the radical alternatives remain taboo. Yet the films’ incoherence—the proof that the issues and conflicts they dramatize can no longer even appear to be resolvable within the system, within the dominant ideology—testifies eloquently to the logical necessity for radicalism.

Third, that any promise of a radical vision they may seem to hold will have to be stored away for the future. Cruising, shot in 1979, already seemed an anachronism when it was released in 1980: in the midst of the parade of demoralizingly “moral” reactionary movies heralded in the late 70s by Rocky and Star Wars, it sticks out like a sore thumb. In the age of Star Trek, Serial, Bronco Billy, Urban Cowboy, and Honeysuckle Rose, when even progressive liberals like Jerry Schatzberg and James Bridges are succumbing without apparent protest to the tide of reaction, recuperation, and reassurance, we can already look back to Hollywood in the 70s as the period when the dominant ideology almost disintegrated.

1. Since this essay was written in 1980, I have discovered two reviews of Cruising, written independently and around the same time, published in the Australian magazine Cinema Papers, October-November 1980. The reviews, by Tom Ryan and Adrian Martin, substantially confirm my own findings while adding interesting insights of their own.

2. Subsequent 80s films on gay themes, released after this essay was originally written (1980), are dealt with in chapter 11 they qualify but do not seriously contradict the account offered here.