CASTRATION

Brian De Palma’s interesting, problematic, frequently frustrating movies are quite obsessive about castration, either literal (Sisters, Dressed to Kill) or metaphorical (all the rest).1 This “Obsession”—the significant title of one of his films—seems a legitimate way into a discussion of his work, its relation to the films of Hitchcock, and its place within 70s Hollywood cinema. In the interests of clarity, I shall preface this discussion with an examination of Freudian castration theory and the use that has been made of it in recent film criticism.

Freud’s own accounts of castration anxiety attribute it to two major sources: The development of the Oedipus complex where the boy fears castration as his logical punishment for desiring the mother and wishing the father dead; the discovery of sexual difference, when he finds that little girls don’t have penises, and becomes afraid that he may lose his. Conversely, there arises here the concept of female castration: the girl, finding that little boys do have penises, fears that she has already lost hers.

It has been thoroughly documented that in Freud’s time castration anxiety (whatever one may think of the theoretical basis baldly outlined above) was also rooted in practical familial realities: little boys were actually threatened with castration as punishment for masturbation, if not directly (“If you do that I’ll cut it off”), then indirectly (“If you do that it will drop off”). That monstrous, much-translated, widely distributed “children’s book” Struwwelpeter—surely among the most disgusting works of literature ever produced, especially given its intentions and presumed readership—testifies eloquently to the reality and pervasiveness of the threat. Similarly, it seems logical to assume that the traumatic shock of the discovery of sexual difference was greatly exacerbated, if not actually produced, by the secrecy with which sexuality was surrounded, the parental insistence on the shamefulness and “dirtiness” of the “private parts,” which must always be concealed. Little information exists as to just how thorough and how widespread through the various social strata change has been. The practice of sex education within the institutionalized educational system and through popular manuals, counseling services, etc., although obviously compromised and co-opted by the bourgeois capitalist establishment (a true sex education would promote revolution), has presumably made some inroads, so that infantile masturbation is more tolerated, and both infantile and parental nudity are more widely accepted, less accompanied by damaging inhibitions. One needs to know what effect this has had on castration anxiety (some, surely, though a study of our current cinema would swiftly suggest that we shouldn’t overrate it). Meanwhile, many film theorists appear to continue to accept castration theory as it came from the mouth of Freud, as if no changes had occurred whatever.

For this, Freud himself is partly to blame. It is one of the paradoxes of his work that, while he strove all his life toward the formulation of a psychoanalytical theory of human history, he had so little awareness of the cultural/historical specificity of his own work. Hence his habitual lapses into an essentialism in which valid and radical discoveries derived from investigations into the neuroses of upper middle-class turn-of-the-century Vienna are assumed to offer permanent and universal insights into the entire human race. For example, his discovery of the Oedipus complex and its multifarious ramifications has clearly proved invaluable as a means toward understanding the construction of the socialized individual within our culture. Yet only recently—such is Freud’s authoritativeness—have we come to realize that the complex is far more likely to be something imposed on children by their parents within the structures of the bourgeois nuclear family, than something that develops inevitably and “naturally” in every child ever born. A constant problem with Freud is that the very cogency of his arguments, combined with this pervasive essentialist fallacy, tends to impose those arguments as representing conditions that are unchangeable. So with castration theory, which is obviously closely bound up with the immense symbolic significance accumulated by “the phallus” in patriarchal society. I am not asserting that, in an achieved socialist-feminist culture, castration anxiety would disappear altogether (it refers, after all, to a part of the anatomy which men are likely to continue to value), but it would clearly be very different in nature and scope, restricted to a perfectly legitimate sensitivity to the possibility of physical mutilation.

For it is when one considers the symbolic extensions of castration anxiety that the problems really thicken. The mystique of the phallus appears to rest upon no more impressive a foundation than the fact that, in childhood (before girls develop breasts, when boys and girls alike may have long or short hair, etc.), it is the one sign that clearly differentiates the sexes. Hence, for patriarchy, it can be invested with the utmost mythic/symbolic importance. There is even, for example, the myth that power, strength, and charisma are somehow attributes of the phallus (a myth most strikingly developed in the work of D. H. Lawrence, whose genius invested it, for a time, with a spurious plausibility). Given the false premise the symbolic extensions are perfectly logical, taking in every form of male power and, especially, those forms that have as their function the domination of women. I list here but a few.

1. Positions of Authority Under this rubric fall the Father and his Law (both terms to be understood literally and symbolically): the father of the family, the President or King as “father” of the nation, the Pope as “Father of the Church,” together with father figures from ministers of state through judges to policemen (not forgetting university professors). Sometimes, of course, women fill these roles, but, in the overwhelming majority of what is only a tiny minority of cases, only if they are able to convince men that they pose no threat, that they will slot safely in to the patriarchal institutions.

2. Money In capitalist society possession of money is the most obvious manifestation of power; translated beyond the individual into class terms, it is also, of course, the most real one. Hence possession of money equals possession of the phallus, a point magnificently confirmed by such impressive but variously doomed transgressive heroines of the 40s and 50s as Mildred Pierce, Ruby Gentry and Mamie Stover, usurpers of the phallus.

3. The Voice The voice of authority in the home has traditionally been that of the father; for all the myths about American matriarchy: “Stop it, or I’ll tell your father.” Outside the home, all the institutionalized voices of our culture—government, the church, the law, education, the media—have been dominated and controlled by men (occasionally, again, by nonfeminist women, but they are merely individuals rather than representatives of collective authority).

4. The Look In relation to the visual arts, “the look” is logically the most theorized extension of the phallus: see, most obviously, John Berger’s Ways of Seeing and Laura Mulvey’s seminal article Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. The simplest way of examining the male domination of women through the organization of “the look” is the study of advertisements. Two favorite patterns recur insistently, and they roughly correspond to Mulvey’s presentation of Hawks and von Sternberg, respectively. In the case of advertisements featuring both a male and a female, the female looks out at us—or at nothing; the male looks at her, his look becoming the mediation of our own. With advertisements (usually for cosmetics) featuring a female alone, displayed for the camera—for our gaze, our appropriation—without the need of mediation, the male viewer symbolically possesses her through “the look”; the female viewer is encouraged to “be” her, the passive looked-at. It must be added that as soon as we move from advertising to cinema, that is, to narrative, with all its potential tensions, complexities and contradictions, the situation immediately becomes less simple. Mulvey’s article, like so many seminal works, has proved quite inadequate and oversimplified in its actual reading of films: von Steinberg’s work, for example, cannot be seen merely as reproduction/reinforcement of the objectification of women; it also operates consistently as a critique of it. This does not invalidate Mulvey’s premises, which have proved invaluable as a starting point for exploration.

The symbolic phallus has as its logical corollary the notion of symbolic castration: the male fears the loss of power as castration, the powerless woman is already castrated. For a particularly vivid cinematic image of the castrated woman, one might evoke Liv Ullmann in Persona, cowering back against the wall of her hospital bedroom away from the television newscast of the burning monk in Vietnam, appalled not only at horror itself, but at the utter powerlessness of women in a world whose horrors are constructed and perpetrated by men. If one accepts the Freudian premise, then the no-win, Catch-22 situation of women in our culture becomes clear: men hate and fear them because as castrated they perpetually reactivate childhood fears of literal castration, and because they may at any point reject their status as castrated and attempt to appropriate the symbolic phallus. They can be accepted, grudgingly, only if they willingly accept a subordinate position and show themselves to be happy in their own castration. Conversely, any attempt to possess the phallus is simultaneously perceived as a threat to castrate the male: see the extraordinary introduction of Charlton Heston in Ruby Gentry, where Jennifer Jones captures him in the beam of her powerful flashlight, blinding him with its brilliance, violently inverting the looker/looked-at relationship.

The problem (for political purposes, i.e., from the viewpoint of producing fundamental transformation) lies in the relationship between the literal and symbolic levels. One can scarcely doubt that a relationship exists. It is vouched for in popular idiom. Consider, for example, the link between phallus and “look” epitomized in that favorite threat of castration-as-punishment-for-masturbation “Do that and you’ll go blind,” or the common usage of the term “castrating bitch,” signifying the woman’s rebellion (which, of course, can take very “unpleasant” forms) against her assigned passivity and subordination. The psychoanalytical argument (supported by our culture’s pervasive acceptance of the phallus as the major symbol of power) is partly that symbolic castration inevitably reactivates the primal terrors of childhood. Yet it seems essential that the link be broken. If the struggle for women’s liberation is to be won, men must learn to relinquish the domination that is central to socially constructed masculinity, and to relinquish it not in the name of liberal condescension and fair play but as an act that liberates them, too: in psychoanalytical terminology, they must learn to accept castration. Yet it is obviously impossible for anyone, male or female, short of a criminal psychopath, to think the term castration positively. The problem cannot be reduced to one of mere terminology: while the link between the literal and symbolic phallus remains, the term will retain its symbolic relevance. One’s hope must be that as more enlightened attitudes to sex education, nudity, infantile masturbation, and parent/child relations develop, as literal castration fears diminish, the link will gradually weaken to the point where separation becomes possible, and men can view their relinquishment of domination as a relinquishment of a set of social conditions that oppresses everybody. Meanwhile, it is the dramatization of these quandaries—though frequently incoherent and con-fused—that gives De Palma’s work its resonance.

DE PALMA AND HITCHCOCK

The common adverse account of De Palma starts from (and in effect ends at) the charge that he can do nothing but produce imitations. Phantom of the Paradise is a remake of Phantom of the Opera, Scarface a remake of the Hawks classic. Above all, of course, De Palma imitates—or, more brutally, plagiarizes—Hitchcock. I want here to define more precisely the relationship between the two bodies of work.

It has become a critical commonplace that we live in an age of remakes, and in general this can be taken as one sign among many of the bankruptcy of contemporary Hollywood cinema (another closely connected sign is the spinning off of sequels). As the bankruptcy is artistic but not by any means commercial (sequels, especially, are “what the public wants”), one can certainly see this as reflecting the bankruptcy of contemporary American culture, or capitalism in general. First, then, I want firmly to distinguish De Palma’s Hitchcock-inspired films from this widespread tendency: their characteristics are quite distinct. A way of putting this distinctness positively is to say that the relationship of De Palma to Hitchcock is centered on a complex dialectic of affinity and difference, whereas the overwhelming majority of contemporary remakes and sequels are constructed on the simple premise that a formula that worked before will work again.

A brief consideration of De Palma’s two non-Hitchcock remakes will define this distinction further. Phantom of the Paradise belongs, in fact, with the “Hitchcock” films (significantly, it contains an overt Hitchcock reference, what still remains the wittiest parody of the Psycho shower murder) and is related closely to the De Palma thematic. With Hawks, on the contrary, De Palma has shown no affinity whatever: Scarface, for all its distinction, has far more in common than the “Hitchcock” films with the general conglomeration of contemporary remakes. Its weakest aspects are those derived without significant transformation (remade rather than made over) from the original: witness the uninteresting and perfunctory treatment of the incest theme. Everything that really works in the film is new: the explicit and devastating critique of contemporary American capitalism; the extraordinary climactic restaurant scene in which, first, Scarface is denounced by his wife, who walks out on him, and subsequently, Scarface denounces the entire restaurant clientele and walks out on them, retreating into final and irremediable isolation from his society, the audacious “excessive” images (ridiculous, of course, in the eyes of journalist critics who place their notion of the plausible above any attempt to read the film’s symbolic progress) of the protagonist desperately burying his face in a mound of cocaine, emblem at once of his wealth and bankruptcy.

It is interesting that, in an age of generally inert remakes and imitations, there is still such insistence on the Romantic concept of originality. In terms of the Hollywood cinema and its critical reception, the term has become thoroughly debased. A film is perceived as original either if the reviewer is ignorant of its sources or if it imitates a (generally European) model of critically ratified “genius”: when De Palma works his variations of Psycho, this is imitation or plagiarism, whereas when Bob Fosse or Woody Allen imitates Fellini or Bergman this is somehow, mysteriously, evidence of his originality. Debased or not, the cult of originality is of comparatively recent date. Renaissance painting is rich in acknowledged masterpieces which draw from pre-existing models not only their subject (let us say, the Madonna and Child) but their iconography, their composition, their relation of foreground and background, and their deployment of colors. In such a context, originality (and one really needs to substitute another word like authenticity) can be judged only by the use to which the formulas have been put, evaluation becoming a matter of discriminating between the inert and the creative. De Palma’s variations on Hitchcock—confused, unsatisfactory, maddening perhaps—are never inert.

What, then, does De Palma borrow from Hitchcock? Most obviously, certain plot structures: Sisters and Dressed to Kill both derive from Psycho, Obsession from Vertigo, Blow Out (much less closely) from Rear Window (as well as from Antonioni’s Blow Up, as De Palma’s title candidly confesses). Rear Window also provides the basis for specific sequences in Sisters and Dressed to Kill, an influence already anticipated in a hilarious scene in the early Hi, Mom. Beyond these, Carrie owes something to Marnie (the mother/daughter relationship), and Richard Lippe has brilliantly suggested a much less obvious, perhaps unconscious relationship between North by Northwest and The Fury: both are journey movies built on “double chase” structures (the male protagonist both pursued arid pursuer); both plots are activated by an American government secret organization headed by a manipulative father figure (Leo G. Carroll, John Cassavetes); both journeys move progressively from city to country, and culminate in a private and sinister house which the hero must infiltrate; the climax of both shows the hero trying to save a person he loves from falling from a great height. I shall show that, while some of the films follow the original plot structure closely, each of them significantly transforms its meaning.

It is the existence of much deeper affinities that validates De Palma’s borrowings of Hitchcock plot structures; what is at issue is not the cynical appropriation of commercially successful formulas but a symbiotic relationship whose basis is a shared complex of psychological/thematic drives. These are so closely interconnected in the work of both filmmakers that it is difficult to separate them out, but in the interests of clarity we may attempt a list of the major components, restricting the Hitchcock examples to the films De Palma has demonstrably used, a small group of late works.

1. Voyeurism This is already strikingly in evidence in Hi, Mom!, a film made before any clear connections between De Palma and Hitchcock had been established. It is only retrospectively that one connects with Rear Window the sequence in which Robert De Niro, attempting to make a pornographic film, sets up his camera to film his own seduction of Jennifer Salt in the opposite apartment block. As with Hitchcock, the attitude to voyeurism is complex, the desire to watch from a position of secrecy and immunity being both indulged and chastised. Both directors extend this principle to cinematic practice itself, with the spectator as the ultimate voyeur. Rear Window has been widely interpreted as an allegory about cinema; De Palma makes the connection between voyeurism and the visual media explicit, in, for example, the Hi, Mom! sequence just cited and in the magnificent opening of Sisters, and, further extended to include listening, it forms the very basis of Blow Out.

2. Romantic Obsession In Hitchcock, this is always qualified by irony and skepticism: in Vertigo, James Stewart’s obsession with Kim Novak is defined in terms of an impossible and ultimately regressive wish fulfillment fantasy; in Marnie, Sean Connery’s obsession with Tippi Hedren is bound up with his perception of her as dangerous and neurotic, so that one of several factors qualifying the sense of a happy ending is the unanswered question of what happens when she is “cured.” With De Palma, there is less direct ironic commentary on the male characters’ romantic obsession, but it is invariably presented as hopeless, incapable of fulfillment: in Phantom of the Paradise the male protagonist (William Finley), never physically attractive, becomes so hideously disfigured that he cannot even show himself; in Obsession, the object of the hero’s desire turns out to be his own daughter. Sisters most rigorously subjects romantic obsession to criticism, the fixation of Dr. Breton (William Finley again) on Dominique/Danielle being perceived as the desire of the male to construct and possess (and thereby symbolically castrate) the female, depriving her of all autonomy.

3. Male Sexual Anxiety The association of romantic passion with the male power drive has as its corollary the fear of losing that power, the fear of impotence or castration. The subjugation of female desire to male desire, the containment of the female within patriarchal normality, is typically dramatized in Hitchcock’s films as the male’s assertion, as his means of assuaging castration fears, that he and he alone possesses the phallus. Hitchcock’s films—they amount to one of the most eccentric bodies of work within the Hollywood cinema, though our sense of the eccentricity has been partly dulled by familiarity and popular acceptance—are only precariously contained within the patterns of classical narrative. They move obediently toward the formulaic reestablishment of the patriarchal order (the death of Judy, the marriage of Roger Thornhill and Eve Kendall, the elimination of Norman Bates, the cure of Marnie), yet the reestablishment is invariably undercut (by irony, by a sense of desolation arising out of irremediable loss, by a sense of the emptiness, the emotional bankruptcy, of the order itself). No Hitchcock film lacks a sense of disturbance; the degree of that disturbance, varying enormously from film to film, corresponds closely to the degree to which male sexual anxiety is granted reassurance—the difference between, for example, North by Northwest and Vertigo. I should make clear that I do not wish to claim that De Palma’s films are more radical than Hitchcock’s (when one moves away from messages and concentrates on ideological tensions, the notion of what constitutes a radical film becomes obviously problematic). But in certain specific, hence limited, ways, they go further: the alleged structuring principle of classical narrative, the restoration of the patriarchal order, collapses altogether. The most extreme instance is the end of The Fury, a resolution unthinkable in Hitchcock: the “good father” (Kirk Douglas) voluntarily falls to his death after failing to save his son Robin (Andrew Stevens); as Robin dies he transmits his powers to the already psychically endowed daughter/sister figure (Amy Irving); she uses her accumulated telekinetic potency to explode (literally) the evil father figure (John Cassavetes). The “Oedipal trajectory” of classical narrative (see Raymond Bellour’s celebrated reading of North by Northwest), in which the symbolic father is reinstated and the woman is restored to her “correct” (i.e., castrated) position, is here spectacularly negated.

4. Female Sexuality/Energy/Autonomy The necessary corollary of the male’s fear of losing the phallus is the fear that the female may appropriate it. The transgressive female is a recurrent figure throughout Hitchcock’s work; invariably (unlike the majority of her male counterparts) her guilt is real and her own, not a matter of an “exchange”; invariably she is punished by death if her transgression is irrecuperable (Judy in Vertigo is an accessory to murder), by emotional and physical chastisement if her sin is less extreme (like Tippi Hedren in The Birds and Marnie). Superficially, the films lie open to feminist attack in quite obvious ways; on a deeper level they strongly repudiate it. The woman’s punishment is never endorsed, the spectator is never permitted to feel satisfaction in it; what the films finally enact (and in enacting expose) is the intolerable strain that is the cost of the imposition of male dominance.

De Palma, again, carries this even further. The continuity is clear enough: the murder of Angie Dickinson in Dressed to Kill closely parallels the murder of Janet Leigh in Psycho (registered in both cases as the most grotesquely excessive punishment in either director’s work); the anguish and attempted suicide of Sandra (Genevieve Bujold) in Obsession parallels, though much less closely, the death of Judy in Vertigo. But De Palma’s identification with the female position is in general much more unambiguous than Hitchcock’s, and, correspondingly, the male position is much more unambiguously undermined. Female activity and autonomy are not inevitably punished (see the end of The Fury); when punished, the activity is also clearly endorsed, so that the monstrousness of the punishment is fore-grounded. The key film here is Sisters, which I discuss in detail later. For the moment, I shall consider Obsession and its relation to Vertigo (of all Hitchcock’s films, the one in which the mechanisms and motivations of the male power drive are subjected to the most ruthless and uncompromising critique).

The crucial difference between the two films lies in the nature of the heroine’s involvement in the convoluted criminal plot. In Vertigo, Judy’s role is purely instrumental (“You were the victim, I was the tool,” as her letter to Scottie declares); her motivation is money and the man’s favors. In Obsession, although Sandra is involved in the machinations of an evil man, her motivation is autonomous: she is avenging herself and, more important, her mother. The opening of the film sets up the couple as, in the words of Bob (John Lithgow), “this world’s last romantics”; to the ideal romantic couple is added the ideal family. Yet, as father dances with daughter, mother rather pointedly withdraws. Central to the film’s development is the daughter’s growing identification with the mother who, within the structures of the nuclear family, was initially her rival. One of the film’s key moments is when Sandra, many years later and about to become her father’s bride, reads her dead mother’s diary, and the romantic love that is the basis of the entire action is abruptly revealed as a male-imposed illusion: the mother, on her side of the ideal union, felt unhappy and neglected. The film dramatizes, and systematically undermines, two manifestations of the male power drive, the assertion of the phallus: the imposition of romantic love and the potency signified by money. Hence the emotional force of the extraordinary final moments. Courtland (Cliff Robertson) rushes toward the woman who is the seeming reincarnation of his romantic ideal (explicitly, the Beatrice to his Dante, with whom he was going to begin the “vita nuova”) armed with two objects—the suitcase of money that proves the greatness of his love for her, and the gun with which he means to kill her for betraying that love. As the suitcase bursts open and the banknotes are dispersed, she reveals in a word that she is his daughter. The ensuing reunion—ecstatic on her side, profoundly troubled on his—is modeled on the famous climactic moment of Vertigo, the moment (circling lovers, circling camera) of simultaneous fulfillment and disillusionment. Here, however, what is expressed are the triumph of the woman and the defeat of the man (though a defeat he comes, in the final seconds, graciously to accept): the celebration of her identification with the mother, ironically fused with the destruction of romantic illusion.

Genevieve Bujold in Obsession

5. Gender Ambiguity The problematic of castration (both male and female, literal and symbolic) inevitably merges with, and becomes confused with, other questions of sexuality: the social construction of gender roles and the repression of bisexuality, of the masculinity of women and the femininity of men. Psycho (significantly, with Rear Window, the Hitchcock film that most haunts De Palma’s work) produces at its center, and as its problem, the figure of Norman Bates, the feminized male who becomes transformed into the masculinized female, the avenging mother: a figure of extraordinary resonance in relation to all the relationships (both sexual and familial) in the film. In close parallel Dressed to Kill produces as its center Dr. Elliott (Michael Caine), a feminized male so horrified by his own masculinity that he feels compelled to murder any woman who arouses it. The whole film moves toward the explicit statement of castration—Nancy Allen’s detailed description, in the restaurant, of the operation that would have converted Dr. Elliott into a woman. For the contemporary viewer and reader, the ending of the film irresistibly evokes Balzac’s Sarrasine, as read by Roland Barthes in S/Z: the revelation of castration makes it impossible for the heterosexual couple to make love. The question has been raised, in relation to S/Z, as to whether Sarrasine is really about castration or rather about bisexuality; precisely the same question could be asked of Dressed To Kill, which provides no coherent answer.

The other literary reference the film evokes for me, equally irresistibly, is Eliot’s famous cryptic note to part 3 of The Wasteland: “All the men are one man, all the women are one woman, and the sexes meet in Tiresias.” (De Palma has assured me that the use of the name Elliott for his Tiresias is purely coincidental; he also admits to familiarity with Eliot’s poem. What exactly is coincidence?) As fascinating in its suggestiveness as it is infuriating in its incoherence, Dressed to Kill plays intricately throughout on doubles and on ambiguities of sexual identity. The first female transgressor (Angie Dickinson) finds her reflection, even as she dies, in the second (Nancy Allen), as they stretch out hands to each other across the entrance to the elevator; both are reflected in Bobby, Elliott’s female persona, as, in women’s clothes, she wields the castrating razor. Bobby, in turn, finds her double in the masculine police woman assigned to protect Liz (Nancy Allen) but mistaken by her for the killer. An extraordinary sequence using cross-cutting and split screen juxtaposes Liz with Dr. Elliott and both with an actual transsexual being interviewed on television: the man who wants to lose the phallus (literally) mirror-imaged by the woman who wants to acquire it (symbolically, in the form of money—she speculates on the stock exchange, and is involved in business calculations throughout the sequence). Less obvious, but most intriguing of all, Peter (Keith Gordon) becomes, as feminized and asexual male, the echo of the would-be-castrated Dr. Elliott. The original intention was that the role be played by a child; when this proved impractical De Palma made the character a young man without apparently altering his function in the film. The connotations of asexuality may therefore be accidental (but what exactly is accident?). It seems extremely important that the film should produce as its male hero a gentle and feminine character who is excluded (why is never gone into) from becoming the female hero’s lover. The film, in other words, while built on the horrors arising from sexual difference, can see, (like Sisters before it), no resolution of that difference except through castration. (Consider how different the final effect would have been if Peter had been characterized as gay.) This may be why De Palma’s habitual identification with women is accompanied, paradoxically, by an apparent animus against them, the contradiction often expressing itself in the treatment of a single character: Kate (Angie Dickinson) in Dressed to Kill is the most obvious example, but there is also Grace (Jennifer Salt) in Sisters, the major flaw of which is De Palma’s inability to take her seriously. The artistic personality the films define is that of a fundamentally feminine man who, because he is a man within a patriarchal culture, can view his femininity only in terms of castration.

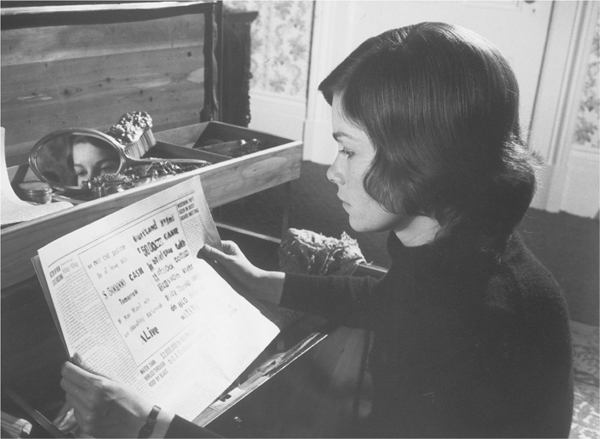

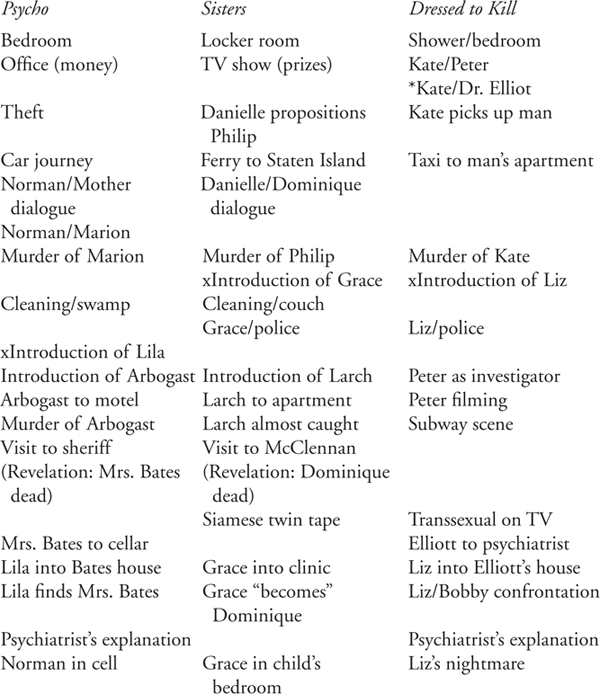

I shall conclude by examining in more detail De Palma’s two finest, most fully realized works to date, Sisters and Blow Out. By way of transition, it is illuminating to formulate more systematically the structural parallels between Psycho, Sisters and Dressed to Kill, and the play of difference those parallels make possible.

In each film a crucial point of transference occurs, a transition from one character to another as the center of interest; in each case the transition and its significance are in key respects quite different:

The above chart, while largely self-explanatory, requires a few elucidatory comments. First, it will be clear that the parallels range from the close and obvious to the relatively esoteric. Second, they do not always obey a parallel chronology: those that occur “out of synch,” as it were, are linked by typographical signs. Third, many of the parallels, whether close or not, in synch or out, serve to highlight the differences between the films and in some cases give those differences richer significance (perhaps, instead of talking about plagiarism critics might begin talking about intertextuality). I shall discuss a few of the more important differences here.

Psycho, from being initially deplored or regarded as a joke, has become something of a critical fetish object, to the extent that one feels a certain trepidation in suggesting that it has any flaws whatever. After a number of viewings of which I long ago lost count, the first half of the film remains as engrossing, and seemingly inexhaustible, as ever; the film picks up again with Lila’s exploration of the Bates house. The half hour in between becomes more tedious with every viewing: shot like a TV movie (“photographs of people talking”), it consists largely of Hitchcock laboriously maneuvering his characters into position for the next incursion into the Bates domain. De Palma in both films solves at a blow the structural problem that defeated Hitchcock and his writer Joseph Stephano in adapting Robert Bloch’s novel: the investigator in the film’s second half witnesses the murder that closes its opening movement, and the narrative hiatus is abruptly bridged.

This strategy has a further extension. The reader may have noticed that my chart of narrative transitions appears to cheat: the second character in each of the De Palma films is not the one who corresponds to Norman Bates (the logical parallel would replace Grace and Liz with, respectively, Danielle/Dominique and Dr. Elliott/Bobby). However De Palma achieves a marked shift of emphasis: where Hitchcock kept Sam and Lila quite nondescript and undercharacterized, mere projections of the curious spectator into the film, De Palma centers our attention on the investigator, who happens to be in both instances a woman. One might loosely claim Lila Crane as a transgressor: she assumes an active role and an active “look.” But women have explored sinister houses virtually since cinema began. Grace and Liz are transgressors in far more specific ways; they are also more drastically punished. The shift, one might argue, is motivated by De Palma’s characteristic disturbance about women (identification with/animus against).

Accordingly, the meaning of the transition changes significantly, the centering of the conflict on female transgression becoming increasingly explicit and emphatic. All three films move toward the revelation that the woman, usurper of “the look,” must finally confront. Lila faces, in the form of the dead/alive Mrs. Bates, the ultimate horror of the Oedipal tensions produced by the nuclear family; Grace is forced to witness and participate in the castration of woman under patriarchy; Liz, the appropriator of the symbolic phallus, confronts her inverted mirror image and the horror of a sexual difference that can neither be accepted nor transcended.

Sisters

I have argued elsewhere that horror films can be profitably explored from the starting point of applying a simple all-purpose formula, Normality is threatened by the Monster, and that the formula offers three variables with which to work on the analysis of individual films: the definition of normality, the definition of the monster, and, crucially, the definition of the relationship between the two. As a general rule, the less easy the application, the more complex and interesting the film, though no horror film is entirely simple (i.e., with the monster as purely external threat). Take War of the Worlds (Haskin/Pal, 1953) as an example of the horror film at its simplest as far as meaning is concerned. On the surface, Normality = humans, the Monster = Martians; this covers (not very concealingly) a second level where Normality = the free world and the Monster = Communism (the news bulletins in the film name every major country but Russia as the victim of Martian invasion, an absence that leaves the audience to make a simple deduction). Yet even here the threat only appears purely external. The topical fear of Communist invasion in its turn covers a more fundamental fear, the true subject of horror films—the fear of the release of repressed sexuality. The Martian machines are blatantly phallic, with their snakelike probing and penetrating devices, it is the monogamous heterosexual couple (Classical Hollywood’s habitual basic definition of normality) who are centrally threatened, and the film ends with God and Nature combining, at the very moment when the whole world (i.e., normality) is in imminent danger of destruction, to reunite the couple, annihilate the invaders, and restore repression. The film is also crudely sexist. Lip service is paid to female equality, the heroine being supplied with an M.A. in technological science, but once that’s been established, her only function is to scream every time a Martian phallus pokes in through her window. War of the Worlds, then, to which the formula applies very simply, is like thousands of other films reducible to the simplest and crudest patriarchal ideology.

The great horror movies demand a far more complex application of the formula. For example, I Walked with a Zombie is structured on a complicated set of oppositions (crudely reducible to normality/monster) which the film systematically undermines until everything is in doubt; in Psycho normality and the monster no longer function even superficially as separable opposites but exist on a continuum which the progress of the film traces. Psycho is clearly a seminal work, definitively establishing (if hardly inventing) two concepts crucial to the genre’s subsequent development: the monster as human psychotic/schizophrenic and the revelation of horror as existing at the heart of the family. The continuum is represented not only by the transition from Marion Crane to Norman Bates, but by the succession of references to parent/child relationships that starts with Marion’s mother’s picture on the wall overseeing the respectable steak dinner and culminates in Mrs. Bates. Since Psycho, and particularly in the 70s, the definition of normality has become increasingly uncertain, questionable, open to attack; accordingly, the monster becomes increasingly complex.

The force and complexity of Sisters, De Palma’s finest achievement prior to Blow Out and one of the great American films of the 70s, can be demonstrated through the ways in which it responds to the formula. Traditional normality no longer exists in the film as actuality but only as ideology—as what society tries, at once unsuccessfully and destructively, to impose. Specifically, it is what Grace Collier’s mother wants to do to Grace (Jennifer Salt) and what Emile Breton (William Finley) wants to do to Danielle/Dominique (Margot Kidder). Grace’s mother speaks condescendingly of her daughter’s journalist career as her “little job,” regards it as a phase she is going through, looks forward to her marrying, and proposes an appropriate suitor; Emile’s obsessive project has been to create Danielle as a sweet, submissive girl at the increasing expense of Dominique (eventually provoking Dominique’s death). Normality, therefore, is still marriage, the family and patriarchy—all that the monster of the horror movie has always implicitly threatened. But whereas in the traditional horror film there had to be an appearance of upholding normality, however sympathetic and fascinating the monster, in Sisters normality is not even superficially endorsed. If the monster is defined as that which threatens normality, it follows that the monster of Sisters is Grace as well as Danielle/Dominique—a point the film acknowledges in the climactic hallucination/flashback sequence wherein Grace becomes Dominique, joined to Danielle as her Siamese twin, the film’s privileged moment on which its entire structure hinges. Simply, one can define the monster of Sisters as women’s liberation; adding only that the film follows the time-honored horror film tradition of making the monster emerge as the most sympathetic character and its emotional center.

Sisters analyzes the ways in which women are oppressed within patriarchal society on two levels, the professional (Grace) and the psychosexual (Danielle/Dominique). Grace’s progress in the film can be read as a depiction of how women are denied a voice. At times this can be taken literally: the police inspector denies Grace the right to ask questions or to make verbal interventions; in the asylum she is prevented from using the phone, her attempts to assert her sanity (and even her own name) are overruled, and she is silenced by being put to sleep. More widely, her professional potency is frustrated at every step: the police refuse to believe her story; her editor habitually gives her ludicrous assignments such as the convict who has carved a model of his prison out of soap; her mother tries to make her normal. Even when she gets permission to pursue her investigations, it must be under the guidance of a male private detective (Charles Durning), who rejects her spontaneous ideas in favor of the methods he has been taught in training school. Finally, rendered powerless by a drug, she is given her words by Emile Breton: all she will be able to repeat when she wakes up is “There was no body because there was no murder.” At the end of the film she is reduced to the role of child, tended by her mother, surrounded by toys, and denying the truth of which she once alone had possession.

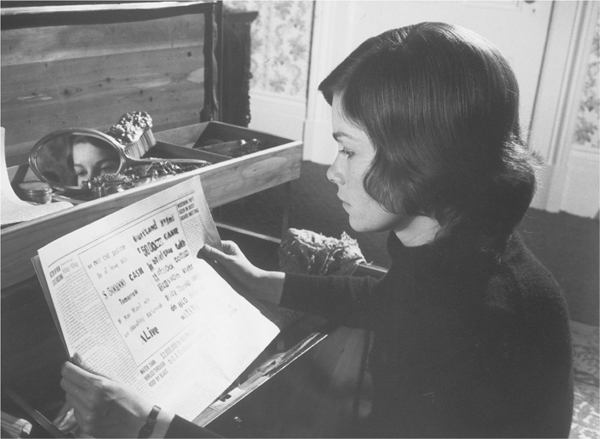

Also—and this is where the Hitchcock/De Palma fascination with voyeurism becomes incorporated significantly into the film’s thematic structure—Grace transgresses by her desire to usurp the male prerogative of “the look.” The opening of Sisters succinctly establishes the gaze as another means of male dominance: Danielle is blind; not only does Philip watch her begin to undress, but we, the cinema audience (thus defined by identification as male), also watch. This is of course immediately and brilliantly undercut: we discover that, having allowed ourselves to be drawn into the voyeuristic act, we have identified ourselves less with Philip than with the lewd and philistine panel (with male and female members) of a particularly mindless TV show. But, having established looking as a theme at the outset, De Palma can take it up again later when Grace aspires to the look of dominance, the look that will give her knowledge. It is for this that she is most emphatically punished: the hallucination sequence is introduced by Emile’s telling her that, as she wanted to see, she will now be forced to witness everything, and is punctuated by huge close-ups of her terrified eye. What Grace sees is the ultimate subjugation (castration) of woman by man.

When Danielle/Dominique murders Philip, her attack is on the two organs by which male supremacy is most obviously enforced, the phallus and the voice; the logic of the film perhaps would also demand that she blind him. Through the presentation of Danielle/Dominique the theme of women’s oppression is given another dimension on an altogether more radical level. Crucial to it is the opposition the film makes between “freaks” and mad people. Freaks are a product of nature; the insane are a product of society (normality). The two mad people we see are simply carrying to excess two of society’s most emphasized virtues, tidiness and cleanliness, the man obsessively trimming hedges with his shears in the night, the woman with her cleaning cloth terrified of the germs that can be transmitted through the telephone wires; both pervert the “virtue” into aggression. (One might note here that the detective’s van assumes two disguises in the course of the film: first that of a house-cleaning firm, later that of Ajax Exterminators.)

Freaks, on the other hand, are natural: it is normality that names, degrades, rejects or seeks to remold them (see Danielle’s horror, in the hallucination sequence, not of being a freak but of being named as one). The morality of using real freaks (the photographs of genuine Siamese twins in the videotape Grace is shown, the various freaks discernible in the hallucination sequence) may be touched on here, with the essential point made by comparing De Palma’s use of them with Michael Winner’s in the worst—most offensive and repressive—horror film of the 70s, The Sentinel. Winner, with his usual taste and humanity, uses real freaks, unforgivably, for their (socially defined) ugliness, to represent demons surging up out of hell. De Palma uses them, in a film that consistently and subversively undercuts all assumptions of the normal, to symbolize everything that normality cannot cope with or encompass. To object, in this context, to the association of women’s liberation with freaks would be simply to endorse normality’s definition. Freaks only become freaks when normality names them; to her mother, as to the police inspector, Grace is clearly a freak—hence the mother’s appearance with a camera in the hallucination sequence where Grace becomes Dominique. Danielle/Dominique function both literally and symbolically: literally, as freaks whom normality has no place for, must cure, hence destroy; symbolically, as a composite image of all that must be repressed under patriarchy (Dominique) in order to create the nice, wholesome, submissive female (Danielle). Dominique’s rebellion against patriarchal normality took the extreme but eloquent form of killing Danielle’s unborn baby with garden shears; after which Emile killed her by separating her from her twin. What is repressed is not of course annihilated: Dominique continues to live on in Danielle. Further, the point is made (and underlined by repetition in the speech of the priest in the videotape that recurs during the hallucination sequence) that Danielle’s sweetness depends on the existence of Dominique, on to whom all her “evil” qualities can be projected. Equally, Dominique is Danielle’s potency: the scar of separation, revealed by the slow zoom-in to her body as she and Philip make love, is also the “wound” of castration. Having deprived Danielle of her power (creating her as the male ideal of the sweet girl), Emile can realize a union with her only when she (or the repressed Dominique), in turn, has castrated him, signified by his pressing their clasped hands into the blood of his wound.

The intelligence and radicalism of the film are manifested in its refusal to produce a scapegoat, in the form of an individual male character who can be blamed. Philip is an entirely sympathetic figure, Emile ultimately a pathetic one (he loves Danielle in precisely the way ideology conditions men to love women). He is also one of De Palma’s hopeless romantic lovers, played by William Finley who was to fill the same role a year later in Phantom of the Paradise.

Philip, moreover, provides a further extension of the oppression theme by being black. The film at no point presents his color as an issue, but shows it as an issue for white-dominated normality (his prize for his TV appearance is dinner for two in “The African Room”; the police sergeant’s comment is that “those people are always stabbing each other”). The amiable private investigator asserts his authority over Grace because he is placed in that position. The final image of him (last shot of the film) up a telegraph pole by a tiny railway depot somewhere in remote Quebec watching the sofa containing Philip’s body, with nobody left alive to collect it, is at once funny and poignant. The assertion of male dominance in the film is shown everywhere as destructive, nowhere as successful: it is variously misguided, disastrous, and futile.

One must not, however, look to Sisters for any optimistic portrayal of liberation. If the horror film of the 70s has lost all faith in normality, it simultaneously sees all that it repressed (the monster) as, through repression, perverted beyond redemption. In its apocalyptic phase, the horror film, even when it is not concerned literally with the end of the world (The Omen), brings its own world to cataclysm, refusing any hope of positive resolution (see, to name three distinguished and varied examples, Carrie, God Told Me To, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre). The most disquieting aspect of Sisters is that the two components of its composite monster, Grace and Danielle/Dominique, are in constant and unresolved antagonism. They operate on quite distinct levels of consciousness: Danielle tells Philip near the beginning of the film that she is not interested in women’s liberation; Grace clearly is, but only on the professional level. Even when forced together (as Siamese twins) they are constantly straining apart. The deeper justification for the use of split screen (which also works brilliantly on the suspense level) is that it simultaneously juxtaposes and separates the two women, presenting them as parallel yet antagonistic.

The question as to whether Sisters is really about the oppression of women or is “just” a horror movie is one that I decline to discuss. It is, however, illuminating to place it beside a Hollywood film whose concern with women’s liberation is conscious and overt, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. Alice (a charming, indeed disarming, film) is a perfect example of what Roland Barthes calls “inoculation”: ideology inoculates itself with a small dose of criticism in order to distract attention from its fundamental evils. The opening of the film (after the childhood prologue) depicts an impossible marital situation, wherein the woman is ignored, taken for granted or maltreated, her role as wife and mother being assumed to be all she needs. The end of the film unites her with a man who will treat her well, permit discussion, and perhaps allow her to pursue her own career on the side: the patriarchal order is restored, suitably modified. Sisters is beyond such inoculation.

Blow Out

Both Rear Window and Blow Out have as their underlying premise male castration anxiety and the search for reassurance or compensation. This is obvious in Hitchcock’s film, which takes as its starting point Jefferies’ broken leg and the transference of phallic power to “the look”: one of Hitchcock’s funniest and most serious gags is the systematic growth of the look-as-phallus-substitute—eyes, binoculars, a huge telescope. In Blow Out Jack Terry (John Travolta) bears no physical mark of castration; yet he shows no sexual interest in women (although he feigns it when it suits his purposes), and all his energies are displaced on to his work as sound man. The sequence that follows the credits—Jack on the bridge in the woods recording his sound effects—visually establishes his microphone as phallic symbol. Where Jefferies finds compensatory power in looking, Jack finds it in listening; in both cases, the man’s sense of his own manhood, conceived essentially in terms of dominance, comes to depend upon his proving the truth of what he believes he has seen or heard; both films move toward his confrontation with his alter ego, the spied-upon, in each case a murderer.

Weaving through Blow Out like a guiding thread is the suggestion that Jack’s “disinterested” search for truth is not in fact disinterested at all: its true motivation is the assertion of his own ego. The film is also quite clear that this assertion is realized at the expense of women. The connection with Rear Window has been often noticed; as far as I know, no one has commented on Blow Out’s relationship to another great Classical Hollywood movie, Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat. There Debbie (Gloria Grahame), a gangster’s kept woman, becomes attracted to the hero, Bannion (Glenn Ford), and specifically to his “disinterested” nobility; she dies helping him successfully extirpate the city’s corruption. Bannion’s motivation is presented as mixed: his integrity is indirectly responsible for the death of his wife, from which point he is motivated as much by the desire for personal revenge as by a desire to clean up the city. His responsibility for Debbie’s death is kept carefully ambiguous. He leaves her a gun, ostensibly for her own protection, perhaps (unconsciously?) so that she will do what he, with his nobility and integrity, cannot: murder Martha Duncan. One might say that the subtext of The Big Heat (the hero’s use of a woman to whom he feels morally superior to serve his own ends, and his responsibility for her death) becomes the overt, dominant text of Blow Out. One can trace its development throughout the film.

1. During the scene on the bridge, Jack records—at first inadvertently—the conversation of a young couple. The man is leading the woman on, plainly bent on seducing her against her better judgment. Jack’s knowing smile aligns him at the outset with the manipulative male, at which moment the girl becomes aware of his presence, and his voyeuristic complicity is made explicit (“What is he, a peeping tom or something?”).

2. The establishment of Jack’s relationship with Sally (Nancy Allen) in the hospital is already characterized by deception, albeit of an innocent if patronizing sort: knowing that she is about to succumb to sedation, he tells her he will fetch her clothes so that she can leave.

3. When he discovers what he has recorded (the sound of a gunshot, establishing the “blow out” as nonaccidental), he attempts to enlist Sally’s aid. When she resists, he immediately abandons rational argument and resorts to emotional blackmail (“I saved your life, the least you can do is have a drink with me”). The entire sequence is very interesting in its relation to audience expectations. He has brought her to a motel bedroom and has stayed there himself; the conventions of Hollywood narrative demand that he show at least some sexual interest, but he shows none, spending the night obsessively replaying his tape. In the context of De Palma’s relationship to Hitchcock, the parallel here would seem to be with Vertigo (the man rescues the woman from drowning and puts her to bed), a parallel that underlines Jack’s sexual indifference.

4. When they meet for a drink, Jack deliberately manipulates Sally into missing the train that would take her to a safe seclusion. His method is to feign interest in her professional accomplishments as makeup artist. When she realizes that she is being both exploited and patronized (“You’re not interested in this at all…. You just kept me talking so that I’d miss my train”), he switches abruptly to the use of his own attractiveness and supposed personal interest in her (“No, that’s not true, Sally, I just didn’t want you to go”). In fact, Sally’s job and Jack’s job offer suggestive parallels: she falsifies people’s appearances by applying makeup, he falsifies bits of film by applying sound effects.

5. Jack finds that all his tapes have been erased. The film’s midpoint/turning point is thus a form of symbolic castration whose importance De Palma marks by two of his most “excessive” rhetorical gestures, a seemingly interminable, dizzying circular pan and a vertiginous overhead shot. After that Jack’s more or less subtle manipulation of Sally escalates into overt bullying.

6. In the scene where Jack makes Sally miss her train, he subsequently confesses his responsibility for the death of Freddie Corvo, the direct consequence of Jack’s wiring him (again, in the apparent interests of truth, and in the real interests of Jack’s own ego). In the final scenes, he wires Sally when he sends her to her fatal meeting with Burke, the bogus Frank Donohue, without any sense of repeating his own earlier actions. He is too preoccupied with his own self-vindication (“I’m going to cover all the bases. Nobody’s going to fuck me this time”), and his concern is for the safety, not of Sally, but of Manny Karp’s film.

If the subject of Sisters is the oppression (castration) of women under patriarchy, Blow Out can be read as its corollary: an uncompromising critique of the machinations of the male ego to assert its possession of the phallus. It is crucial that Jack Terry (one of Travolta’s most disciplined performances) remain a sympathetic character throughout: the male spectator is permitted no comforting or distancing superiority (“Of course, I wouldn’t behave like that”). The critique, however, goes far beyond the development of linear narrative I have so far described. Supporting and extending it is a systematic symbolic structure built upon the figure of the double. Jack, as sympathetic character, as the film’s main identification figure, finds significant reflection in three other male characters, none of whom is sympathetic in the least and one of whom is explicitly psychopathic. I deal with them in ascending order of importance.

Male Manipulation in Blow Out

Dennis Franz and Nancy Allen

John Travolta and Nancy Allen

Frank Donohue. The connection between Jack and Donohue (the investigative reporter for “City News” and illustrious television personality) is the only one not underlined by either narrative echoes or the reiterative use of specific cinematic codes, perhaps because it is the simplest and most obvious. Donohue’s verbal manipulation of Jack closely reflects Jack’s of Sally. He is another, cruder example of ego-serving masquerading as the search for truth. As he persuades Jack to “go public” on his news show, the “disinterested” desire to reveal truth quickly slips into “It’s a great story.” When Jack initially resists—as Sally initially resisted—Donohue moves immediately into a direct appeal to Jack’s need for personal recognition: “Frank Donohue believes it. And he’s got eight million people every night that watch him…. All those sons of bitches are going to believe Jack Terry’s story, I promise you that.” Jack capitulates.

Manny Karp. By withholding crucial information from her, Karp has manipulated Sally into playing her role in the blow out plot, closely anticipating Jack’s use of her (subtler, but scarcely less reprehensible) in the plot he is trying to construct. Karp’s motivation, pure material greed, is altogether cruder than Jack’s, yet the stripping away of the camouflage of disinterestedness merely reveals the drive of personal egoism the more clearly (Karp’s phallus is money). Hence the overhead shot when Jack discovers that his tapes have been erased is precisely answered by the overhead shot when Sally knocks Karp out and steals his film, source of all his expectations.

Burke. The film’s key scene—its “primal scene,” one is tempted to say—juxtaposes (when “what actually happened” is revealed) Burke, Karp and Jack Terry: Burke causes the death of “the father” (Governor George McRyan, probable future President of the United States), Karp films it, Jack records it: all three are voyeurs at a scene where “the father” is caught with a woman in flagrante delicto. Burke and Jack are subtly paralleled throughout the film. Both begin by doing a professional job, both continue with that job for their personal satisfaction after their employers have disowned it. Jack’s personal satisfaction involves the manipulation of women, Burke’s is the murder of women; both drives come together in the death of Sally, caused by Jack, executed by Burke. Both secretly listen in to and record other people’s conversations (Jack and the young couple at the bridge, Burke’s tapping of Jack’s phone). Jack’s responsibility for the death of Freddie Corvo is directly linked to Burke’s murder of the prostitute at the station: each is a death-by-hanging, in a public washroom. Both men, and their responsibility for people’s deaths, are associated by wire: Jack “wires” Freddie Corvo and “wires” Sally; Burke uses wire as his murder weapon. Finally, Jack’s hysterical execution of Burke at the film’s climax closely imitates Burke’s mutilation of his victims by multiple stab wounds in the belly. The effect is similar to that of Ethan Edwards’ scalping of Scar in The Searchers: the hero inadvertently acknowledges his affinity with the villain by duplicating his actions.

Blow Out strikingly combines the overtly political concerns of Hi, Mom! with the sexual politics of De Palma’s Hitchcock variations. The attitude to the American political system is characteristically pessimistic: the electorate can only choose between corrupt liberalism and corrupt conservatism, the corruption presented as all-pervading and irremediable. One would scarcely wish to argue with such a view. The problem is, of course, the one I have already indicated in relation to progressive Hollywood cinema generally, but in De Palma’s work (and this is both its major distinction and its major limitation) it reaches its most extreme expression: the blockage of thought arising from the taboo on imagining alternatives to a system that can be exposed as monstrous, oppressive, and unworkable but which must nevertheless not be constructively challenged. Cynicism and nihilism: the terms can no more be evaded in relation to De Palma than in relation to Altman. Obviously, De Palma’s work suffers—as any body of work must—from an inability to believe, not necessarily in systems and norms that actually exist, but in any imaginable alternative to them. Yet it seems to me that his work is less vulnerable to attack along these lines than Altman’s. At least he never hides behind the superior snigger, never treats his characters or his audience with contempt, and in his best films his thematic concerns achieve remarkably complete realization. Undoubtedly compromised from a purely feminist or purely radical viewpoint, his films offer themselves readily—one might say generously—to appropriation by the Left.

Blow Out explicitly invites us to look for connections between its two political levels, the national and the sexual: the television newscaster, reporting on the discovery of the body of Burke’s first female victim, asks what connection can be made between the “upcoming Liberty Day celebrations” and the pattern of the wounds in the shape of the Liberty Bell. In fact, the motivation for the murders combines the political and the sexual: Burke was initially employed by the right wing to discredit the liberal McRyan; the murder of Sally, politically expedient, is to be disguised to look like one of a series of sex crimes; and in effect that is precisely what the killings are (Burke clearly enjoys his work). Politics is presented as rivalry between males, even the most liberal of whom is not above exploiting women: when he dies, McRyan (presented as a Kennedy-type—the implicit reference to Chappaquiddick has been much noticed) is cheating on his wife and using a prostitute. Above all, the film’s unifying theme of male ego-boosting masquerading as disinterestedness extends to the political level, is seen, in fact, as the defining characteristic of American party politics.

The climactic sequence of Blow Out, where everything comes together, seems to me among the most remarkable achievements of modern Hollywood cinema: the excess, the flamboyance, the cinematic rhetoric, are here entirely earned by the context. As Sally dies, the Liberty Bell rings out: the irony (as crude and obvious as you please) is, in its savage bitterness, the culmination of the whole film. The celebration of a liberty created by males, for males, at the expense of women, within a culture the film has characterized as at every level corrupt and manipulative, coincides with the death of its latest victim. After which, Jack, distraught, his responsibility for what has happened forced home, cradles Sally’s body against a background of orgasmically exploding fireworks: an object lesson in the cost of phallic assertion. What is there left for him to do—given the impossibility, within De Palma’s work and the Hollywood cinema, of envisaging and dramatizing political alternatives, whether sexual or national—but to give Sally’s death scream to the producer of a schlock horror movie? The final moments reveal the action’s hideous cynicism as the male protagonist’s desperate self-laceration. For me, no film evokes more overwhelmingly the desolation of our culture.

1. Since this chapter was written, Body Double (though it is far from being among De Palma’s best films) has amply confirmed its argument.