FANTASY AND IDEOLOGY IN THE REAGAN ERA

THE LUCAS-SPIELBERG SYNDROME

The crisis in ideological confidence of the 70s visible on all levels of American culture and variously enacted in Hollywood’s “incoherent texts,” has not been resolved: within the system of patriarchal capitalism no resolution of the fundamental conflicts is possible. Instead, it has been forgotten, though its specter, masquerading as idealized nostalgia for lost radicalism, still intermittently haunts the cinema (The Big Fix, The Big Chill, Return of the Secaucus Seven). Remembering can be pleasant when it is accompanied by the sense that there is really nothing you can do any more (“Times have changed”). Vietnam ends, Watergate comes to seem an unfortunate aberration (with a film like All The President’s Men actually feeling able, though ambiguously, to celebrate the democratic system that can expose and rectify such anomalies); the Carter administration, promising the sense of a decent and reassuring liberalism, makes possible a huge ideological sigh of relief in preparation for an era of recuperation and reaction. Rocky and Star Wars—the two seminal works of what Andrew Britton (in an article in Movie 31/32 to which the present chapter is heavily indebted) has termed “Reaganite entertainment”—appear a few years before Reagan’s election, and are instant, overwhelming commercial successes. Their respective progenies are still very much with us.

Reassurance is the keynote, and one immediately reflects that this is the era of sequels and repetition. The success of Raiders of the Lost Ark, E. T., and the Star Wars movies is dependent not only on the fact that so many people go to see them, but also that so many see them again and again. The phenomenon develops a certain irony in conjunction with Barthes’ remarks on “rereading,” in S/Z: “Rereading [is] an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us ‘throw away’ the story once it has been consumed (‘devoured’), so that we can then move on to another story, buy another book, and which is tolerated only in certain marginal categories of readers (children, old people, and professors).”

Clearly, different kinds of rereading occur, (children and professors do not reread in quite the same way or for the same purpose): it is possible to “read” a film like Letter from an Unknown Woman or Late Spring twenty times and still discover new meanings, new complexities, ambiguities, possibilities of interpretation. It seems unlikely, however, that this is what takes people back, again and again, to Star Wars.

Young children require not-quite-endless repetition—the same game played over and over. When at last they begin to weary of exact repetition they demand slight variation: the game still easily recognizable, but not entirely predictable. It can be argued that this pattern forms the basis for much of our adult pleasure in traditional art. Stephen Neale, in one of the very few useful works on the subject (Genre, British Film Institute, 1980), discusses the Hollywood genres in such terms. The distinction between the great genre movies and the utterly uncreative hack work (between, say, Rio Bravo and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance on the one hand, and the Roy Rogers or Hopalong Cassidy series on the other) lies very largely in the relationship between the familiar and the surprising—in the length of the leap the spectator is asked to make from generic expectations to specific transformations, the transformations being as much ideological as conventional. The repetition-and-sequel pattern of the 80s is obviously of a very different order: despite the expensiveness of the films and their status as “cultural event,” it is closer to Roy Rogers than to Ford and Hawks. The satisfactions of Star Wars are repeated until a sequel is required: same formula, with variations. But instead of a leap, only an infant footstep is necessary, and never one that might demand an adjustment on the level of ideology.

Hence the ironic appositeness of Barthes’ perception that rereading is tolerated in children. The category of children’s films has of course always existed. The 80s variant is the curious and disturbing phenomenon of children’s films conceived and marketed largely for adults—films that construct the adult spectator as a child, or, more precisely, as a childish adult, an adult who would like to be a child. The child loses him/herself in fantasy, accepting the illusion; the childish adult both does and does not, simultaneously. The characteristic response to E. T. (heard, with variations, over and over again) was “Wasn’t it wonderful?” followed instantly by a nervously apologetic “But of course it’s pure fantasy.” In this way, the particular satisfactions the films offer—the lost breast repeatedly rediscovered—can be at once indulged and laughed off. That the apology (after all, the merest statement of the obvious) has to be made at all testifies to the completeness of the surrender on another level to the indulgence.

It remains to define just what those satisfactions are, the kinds of reassurance demanded and so profitably supplied. It will be scarcely surprising that they—as it were, incidentally and obliquely—diminish, defuse, and render safe all the major radical movements that gained so much impetus, became so threatening, in the 70s: radical feminism, black militancy, gay liberation, the assault on patriarchy. Before cataloguing them, however, it is as well to foreground certain problems that arise in discussing (and attacking) the films. It is, in fact, peculiarly difficult to discuss them seriously. The films themselves set up a deliberate resistance: they are so insistently not serious, so knowing about their own escapist fantasy/pure entertainment nature, and they consistently invite the audience’s complicity in this. To raise serious objections to them is to run the risk of looking a fool (they’re “just entertainment,” after all) or, worse, a spoilsport (they’re “such fun”). Pleasure is indeed an important issue. I had better confess at once that I enjoy the Star Wars films well enough: I get moderately excited, laugh a bit, even brush back a tear at the happy endings, all right on cue: they work, they are extremely efficient. But just what do we mean when we say “they work”? They work because their workings correspond to the workings of our own social construction. I claim no exemption from this: I enjoy being reconstructed as a child, surrendering to the reactivation of a set of values and structures my adult self has long since repudiated, I am not immune to the blandishments of reassurance. Pleasure itself, in fact, is patently ideological. We may be born with the desire for pleasure, but the actual gratifications of the desire are of necessity culturally determined, a product of our social conditioning. Pleasure, then, can never be taken for granted while we wish to remain adult; it isn’t sacrosanct, purely natural and spontaneous, beyond analysis which spoils it (on many levels, it is imperative that our pleasure be spoiled). The pleasure offered by the Star Wars films corresponds very closely to our basic conditioning; it is extremely reactionary, as all mindless and automatic pleasure tends to be. The finer pleasures are those we have to work for.

I do not want to argue that the films are intrinsically and uniquely harmful: they are no more so than the vast majority of artifacts currently being produced by capitalist enterprise for popular consumption within a patriarchal culture. In many ways they resemble the old serials (Buck Rogers, Superman, Batman, etc.) that used to accompany feature films in weekly installments as program fillers, or get shown at children’s matinees. What I find worrying about the Spielberg-Lucas syndrome is the enormous importance our society has conferred upon the films, an importance not at all incompatible with their not being taken seriously (“But of course, it’s pure fantasy”): indeed, the apparent contradiction is crucial to the phenomenon. The old serials were not taken seriously on any level (except perhaps by real children, and then only young ones); their role in popular culture was minor and marginal; they posed no threat to the co-existence of challenging, disturbing or genuinely distinguished Hollywood movies, which they often accompanied in their lowly capacity. Today it is becoming difficult for films that are not like Star Wars (at least in the general sense of dispensing reassurance, but increasingly in more specific and literal ways, too) to get made, and when they do get made, the public and often the critics reject them: witness the box office failure of Heaven’s Gate, Blade Runner, and King of Comedy.

These, then, are what seem to me the major areas in which the films provide reassurance. I have centered the argument in the Star Wars films (E. T. is dealt with separately afterward), but it will be obvious that most of my points apply, to varying degrees, over a much wider field of contemporary Hollywood cinema.

1. Childishness I cannot abandon this theme without somewhat fuller development. It is important to stress that I am not positing some diabolical Hollywood-capitalist-Reaganite conspiracy to impose mindlessness and mystification on a potentially revolutionary populace, nor does there seem much point in blaming the filmmakers for what they are doing (the critics are another matter). The success of the films is only comprehensible when one assumes a widespread desire for regression to infantilism, a populace who wants to be constructed as mock children. Crucial here, no doubt, is the urge to evade responsibility—responsibility for actions, decisions, thought, responsibility for changing things: children do not have to be responsible, there are older people to look after them. That is one reason why these films must be intellectually undemanding. It is not exactly that one doesn’t have to think to enjoy Star Wars, but rather that thought is strictly limited to the most superficial narrative channels: “What will happen? How will they get out of this?” The films ore obviously very skillful in their handling of narrative, their resourceful, ceaseless interweaving of actions and enigmas, their knowing deployment of the most familiar narrative patterns: don’t worry, Uncle George (or Uncle Steven) will take you by the hand and lead you through Wonderland. Some dangers will appear on the way, but never fear, he’ll also see you safely home; home being essentially those “good old values” that Sylvester Stallone told us Rocky was designed to reinstate: racism, sexism, “democratic” capitalism; the capitalist myths of freedom of choice and equality of opportunity, the individual hero whose achievements somehow “make everything all right,” even for the millions who never make it to individual heroism (but every man can be a hero—even, such is the grudging generosity of contemporary liberalism, every woman).

2. Special Effects These represent the essence of Wonderland Today (Alice never needed reassurance about technology) and the one really significant way in which the films differ from the old serials. Again, one must assume a kind of automatic doublethink in audience response: we both know and don’t know that we are watching special effects, technological fakery. Only thus can we respond simultaneously to the two levels of “magic”: the diegetic wonders within the narrative and the extra-diegetic magic of Hollywood (the best magic that money can buy), the technology on screen, the technology off. Spectacle—the sense of reckless, prodigal extravagance, no expense spared—is essential: the unemployment lines in the world outside may get longer and longer, we may even have to go out and join them, but if capitalism can still throw out entertainments like Star Wars (the films’ very uselessness an aspect of the prodigality), the system must be basically OK, right? Hence, as capitalism approaches its ultimate breakdown, through that series of escalating economic crises prophesied by Marx well over a century ago, its entertainments must become more dazzling, more extravagant, more luxuriously unnecessary.

3. Imagination/Originality A further seeming paradox (actually only the extension of the “But of course it’s pure fantasy” syndrome) is that the audiences who wish to be constructed as children also wish to regard themselves as extremely sophisticated and “modern.” The actual level of this sophistication can be gauged from the phenomenon (not unfamiliar to teachers of first-year film studies in universities) that the same young people who sit rapt through Star Wars find it necessary to laugh condescendingly at, say, a von Sternberg/Dietrich movie or a Ford western in order to establish their superiority to such passé simple-mindedness. “Of course it’s pure fantasy—but what imagination!”—the flattering sense of one’s own sophistication depends upon the ability to juggle such attitudes, an ability the films constantly nurture. If we are to continue using the term “imagination” to apply to a William Blake, we have no business using it of a George Lucas. Imagination and what is popularly referred to as pure fantasy (actually there is no such thing) are fundamentally incompatible. Imagination is a force that strives to grasp and transform the world, not restore “the good old values.” What we can justly credit Lucas with (I use the name, be it understood, to stand for his whole production team) is facility of invention, especially on the level of special effects and makeup and the creation of a range of cute or sinister or grotesque fauna (human and non-human).

The “originality” of the films goes very precisely with their “imagination”: window dressing to conceal—but not entirely—the extreme familiarity of plot, characterization, situation, and character relations. Again, doublethink operates: even while we relish the originality, we must also retain the sense of the familiar, the comforting nostalgia for the childish, repetitive pleasures of comic strip and serial (if we can’t find the lost breast we can at least suck our thumbs). Here doublethink becomes almost a synonym for sophistication. The fanciful trimmings of the Star Wars saga enable us to indulge in satisfactions that would have us writhing in embarrassment if they were presented naked. The films have in fact largely replaced Hollywood genres that are no longer viable without careful “it’s pure fantasy” disguise, but for whose basic impulses there survives a need created and sustained by the dominant ideology of imperialist capitalism. Consider their relation to the 40s war movie, of which Hawks’ Air Force might stand as both representative and superior example: the group (bomber crew, infantry platoon, etc.) constructed as a microcosm of multiracial democracy. The war movie gave us various ethnic types (Jew, Polack, etc.) under the leadership of a WASP American; the Lucas films substitute fantasy figures (robots, Chewbacca) fulfilling precisely the same roles, surreptitiously permitting the same indulgence in WASP superiority. Air Force culminates in an all-out assault on the Japanese fleet, blasted out of the sea by “our boys”: a faceless, inhuman enemy getting its just deserts. Today, the Japanese can no longer be called Japs (“One fried Jap going down”—Air Force’s most notorious line), and are no longer available for fulfilling that function (we are too “sophisticated”). However, dress the enemy in odd costumes (they remain faceless and inhuman, perhaps even totally metallic) and we can still cheer our boys when they blast them out of the sky as in the climax of Star Wars, etc.: the same indoctrinated values of patriotism, racism and militarism are being indulged and celebrated.

Consider also the exotic adventure movie: our white heroes, plus comic relief, encounter a potentially hostile tribe; but the natives turn out to be harmless, childlike, innocent—they have never seen a white man before, and they promptly worship our heroes as gods. You can’t do that any more: such movies (mostly despised “B” movies anyway) don’t get shown now, and if we saw one on late-night television we would have to laugh at it. But dress the natives as koala bears, displace the god identity on to a robot so that the natives appear even stupider, and you can still get away with it: the natives can still be childlike, lovable, and ready to help the heroes out of a fix; the nature of the laughter changes from repudiation to complicity.

4. Nuclear Anxiety This is central to Andrew Britton’s thesis, and for an adequately detailed treatment I refer readers to the article cited above. The fear of nuclear war—at least, of indescribable suffering, at most, of the end of the world, with the end of civilization somewhere between—is certainly one of the main sources of our desire to be constructed as children, to be reassured, to evade responsibility and thought. The characteristic and widespread sense of helplessness—that it’s all out of our hands, beyond all hope of effective intervention, perhaps already predetermined—for which there is unfortunately a certain degree of rational justification, is continually fostered both by the media and by the cynicism of politicians: whether we can actually do anything (and to escape despair and insanity we must surely cling to any rational belief that we can), it is clearly in the interests of our political/economic system for us to believe we can’t. In terms of cinema, one side of this fear is the contemporary horror film, centered on the unkillable and ultimately inexplicable monster, the mysterious and terrible destructive force we can neither destroy, nor communicate with, nor understand. The Michael of Halloween and the Jason of the later Friday the 13th films are the obvious prototypes, but the indestructible psychopath of Michael Miller’s Silent Rage is especially interesting because he is actually signified as the product of scientific experimentation with nuclear energy. The other side is the series of fantasy films centered on the struggle for possession of an ultimate weapon or power: the Ark of the Covenant of Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Genesis project of Star Trek II, “the Force” of Star Wars. The relationship of the two cycles (which developed simultaneously and are both extremely popular with, and aimed at, young audiences) might seem at first sight to be one of diametrical opposition (hopelessness vs. reassurance), yet their respective overall messages—“There’s nothing you can do, anyway” and “Don’t worry”—can be read as complements rather than opposites: both are deterrents to action. The pervasive, if surreptitious, implication of the fantasy films is that nuclear power is positive and justified as long as it is in the right, i.e., American, hands. Raiders is particularly blatant on the subject, offering a direct invitation to deliberate ignorance: you’ll be all right, and all your enemies will be destroyed, as long as you “don’t look”; nuclear power is synonymous with the power of God, who is, by definition, on our side. The film is also particularly blatant in its racism: non-Americans are in general either evil or stupid. The disguise of comic strip is somewhat more transparent than the disguise of pure fantasy. Nonetheless, it can scarcely escape notice that the arch-villain Khan of Star Trek II is heavily signified as foreign (and played by a foreign actor, Ricardo Montalban), as against the American-led crew of the spaceship (with its appropriate collection of fantasy-ethnic subordinates). The younger generation of Star Wars heroes is also conspicuously American.

The question has been raised as to whether the Star Wars films really fit this pattern: if they contain a fantasy embodiment of nuclear power it is surely not the Force but the Death Star, which the Force, primarily signified in terms of moral rectitude and discipline rather than physical or technological power, is used to destroy. Can’t they then be read as anti-nuclear films? Perhaps an ambiguity can be conceded (I concede it without much conviction). But moral rectitude has always been an attribute of Americans in the Hollywood war movie; the Death Star was created by the Force (its “dark side,” associated with the evil-non-Americans); and the use of the Force by Luke Skywalker in Star Wars is undeniably martial, violent, and destructive (though Return of the Jedi raises some belated qualms about this). Given the context—both generic and social-political—it seems to me that the same essential message, perhaps more covert and opaque, can be read from the Star Wars trilogy as from Raiders and Star Trek II.

5. Fear of Fascism I refer here not to the possibility of a Fascist threat from outside but from inside: the fear, scarcely unfounded, that continually troubles the American (un-)consciousness that democratic capitalism may not be cleanly separable from Fascism and may carry within itself the potential to become Fascist, totalitarian, a police state. The theme has been handled with varying degrees of intelligence and complexity in a number of overtly political films—supremely, Meet John Doe; but also a range of films from All the King’s Men through Advise and Consent and The Parallax View to The Dead Zone, the theme particularly taking the form of the demagogue-who-may-become-dictator by fooling enough of the people enough of the time. The fear haunts the work of Hitchcock: the U-Boat commander of Lifeboat is of course German and explicitly Fascist, but he is not clearly distinguishable in his ruthlessness, his assumption of superiority and his insidious charm from the American murderers of Shadow of a Doubt and Rope. More generally, how does one distinguish between the American individualist hero and the Fascist hero? Are the archetypes of westerner and gangster opposites or complements? The quandary becomes ever more pressing in the Reagan era, with the resurgence of an increasingly militant, vociferous and powerful Right, the Fascist potential forcing itself to recognition. It would be neither fair nor accurate to describe Rocky and Raiders of the Lost Ark as Fascist films; yet they are precisely the kinds of entertainment that a potentially Fascist culture would be expected to produce and enjoy (what exactly are we applauding as we cheer on the exploits of Indiana Jones?).

The most positively interesting aspect of the Star Wars films (their other interests being largely of the type we call symptomatic) seems to me their dramatization of this dilemma. There is the ambiguity of the Force itself, with its powerful, and powerfully seductive, dark side to which the all-American hero may succumb: the Force, Obi One informs Luke, “has a strong influence on the weak-minded,” as had Nazism. There is also the question (introduced early in Star Wars, developed as the dominant enigma in The Empire Strikes Back, and only resolved in the latter part of Return of the Jedi) of Luke’s parentage: is the father of our hero really the prototypical Fascist beast Darth Vader? By the end of the third film the dilemma has developed quasi-philosophical dimensions: as Darth Vader represents rule-by-force, if Luke resorts to force (the Force) to defeat him, doesn’t he become Darth Vader? The film can extricate itself from this knot only by the extreme device of having Darth Vader abruptly redeem himself and destroy the unredeemable Emperor.

The trilogy’s simple but absolutely systematic code of accents extends this theme in the wider terms of the American heritage. All the older generation Jedi knights, both good and evil, and their immediate underlings, e.g. Peter Cushing, have British accents, in marked contrast to the American accents of the young heroes. The contradictions in the origins of America are relevant here: a nation founded in the name of freedom by people fleeing oppression, the founding itself an act of oppression (the subjugation of the Indians), the result an extremely oppressive civilization based on the persecution of minorities (e.g., the Salem witch-hunts). Britain itself has of course markedly contradictory connotations—a democracy as well as an imperialist power (“the Empire”), which America inherited. It is therefore fitting that both Obi One and Darth Vader should be clearly signified as British, and that doubt should exist as to which of them is Luke Skywalker’s father, whether literal or moral/political. Hence the films’ unease and inability satisfactorily to deal with the problem of lineage: what will the rebels against the Empire create if not another empire? The unease is epitomized in the final sequence of Star Wars, with its visual reference (so often pointed out by critics) to Triumph of the Will. A film buff’s joke? Perhaps. But Freud showed a long time ago that we are often most serious when we joke. From the triumph of the Force to the Triumph of the Will is but a step.

Parenthetically, it is worth drawing brief attention here to John Milius’ Conan the Barbarian, perhaps the only one of these 80s fantasy films to dispense with a liberal cloak, parading its Fascism shamelessly in instantly recognizable popular signifiers: it opens with a quotation from Nietzsche, has the spirit of its dead heroine leap to the rescue at the climax as a Wagnerian Valkyrie, and in between unabashedly celebrates the Aryan male physique with a singlemindedness that would have delighted Leni Riefenstahl. Its token gay is dispatched with a kick in the groin, and its arch-villain is black. There is an attempt, it is true, to project Fascism on to him (so that he can be allotted the most gruesome of the film’s many grisly deaths), but it is difficult to imagine a more transparent act of displacement.

6. Restoration of the Father One might reasonably argue that this constitutes—and logically enough—the dominant project, ad infinitum and post nauseam, of the contemporary Hollywood cinema, a veritable thematic metasystem embracing all the available genres and all the current cycles, from realist drama to pure fantasy, taking in en route comedy and film noir and even in devious ways infiltrating the horror film. The Father must here be understood in all senses, symbolic, literal; potential: patriarchal authority (the Law), which assigns all other elements to their correct, subordinate, allotted roles; the actual heads of families, fathers of recalcitrant children, husbands of recalcitrant wives, who must either learn the virtue and justice of submission or pack their bags; the young heterosexual male, father of the future, whose eventual union with the “good woman” has always formed the archetypal happy ending of the American film, guarantee of the perpetuation of the nuclear family and social stability.

The restoration of the Father has many ramifications, one of the most important of which is of course the corresponding restoration of women, after a decade of feminism and “liberation.” The 80s have seen the development (or, in many cases, the resurrection) of a number of strategies for coping with this project. There is the plot about the liberated woman who proves she’s as good as the man but then discovers that this doesn’t make her happy and that what she really wanted all the time was to serve him. Thus Debra Winger in Urban Cowboy proves that she can ride the mechanical bull as well as John Travolta but withdraws from competition in order to spend the future washing his socks. Or Sandra Locke in Bronco Billy demonstrates that she can shoot as well as Clint Eastwood but ends up spread out on a wheel as his target/object-for-the-gaze. (The grasp of feminist principle implicit in this—that what women want is to be able to do the same things men do because they envy them so much—is obviously somewhat limited.) The corollary of this is the plot that suggests that men, if need arises, can fill the woman’s role just as well if not better (Kramer vs. Kramer, Author! Author!, Mr. Mom). It’s the father, anyway, who has all the real responsibility, women being by nature irresponsible, as in the despicable Middle Age Crazy, which asks us to shed tears over the burden of “being the daddy,” the cross that our patriarchs must bear.

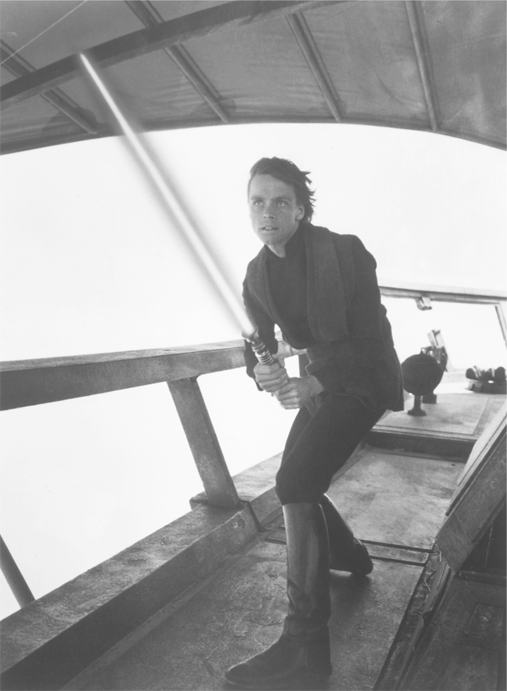

Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker in Return of the Jedi

If the woman can’t accept her subordination, she must be expelled from the narrative altogether, like Mary Tyler Moore in Ordinary People or Tuesday Weld and Dyan Cannon in Author! Author!, leaving the father to develop his beautiful relationship with his offspring untrammeled by female complications. Ordinary People makes particularly clear the brutality to the woman of the Oedipal trajectory our culture continues to construct: from the moment in the narrative when our young hero takes the decisive step of identification with the father/acquisition of this own woman, the mother becomes superfluous to Oedipal/patriarchal concerns, a mere burdensome redundancy. The father, on the other hand, must be loved, accepted and respected, even if he is initially inadequate (Kramer vs. Kramer) or generally deficient, unpleasant or monstrous (Tribute, The Great Santini). Even a non-family movie like Body Heat can be read as another variant on the same pattern. Its purpose in reviving the film noir woman of the 40s so long after (one had innocently supposed) her cultural significance had become obsolete seems to be to suggest that, if women are so perverse as to want power and autonomy, men are better off without them: at the end of the film, William Hurt is emotionally “with” his male buddies even though ruined and in prison, while Kathleen Turner is totally isolated and miserable even though rich and free on a Mexican beach. Clearly, what she really needed was the love of a good man, and as she willfully rejected it she must suffer the consequences. Seen like this, Body Heat is merely the Ordinary People of film noir.

Back in the world of pure fantasy (but we have scarcely left it), we find precisely the same patterns, the same ideological project, reiterated. Women are allowed minor feats of heroism and aggression (in deference to the theory that what they want is to be able to behave like men): thus Karen Allen can punch Harrison Ford in the face near the beginning of Raiders, and Princess Leia has intermittent outbursts of activity, usually in the earlier parts of the movies. Subsequently, the Woman’s main function is to be rescued by the men, involving her reduction to helplessness and dependency. Although Princess Leia is ultimately revealed to be Luke Skywalker’s sister, there is never any suggestion that she might inherit the Force, or have the privilege of being trained and instructed by Obi One and Yoda. In fact, the strategy of making her Luke’s sister seems largely a matter of narrative convenience: it renders romance with Luke automatically unthinkable and sets her free, without impediments, for union with Han Solo. Nowhere do the films invite us to take any interest in her parentage. They play continually on the necessity for Luke to confirm his allegiance to the “good father” (Obi One) and repudiate the “bad father” (Darth Vader), even if the latter proves to be his real father. With this set up and developed in the first two films, Return of the Jedi manages to cap it triumphantly with the redemption of Darth Vader. The trilogy can then culminate in a veritable Fourth of July of Fathericity: a grandiose fireworks display to celebrate Luke’s coming through, as he stands backed by the ghostly figures of Obi One, Darth and Yoda, all smiling benevolently. The mother, here, is so superfluous that she doesn’t figure in the narrative at all—except, perhaps, at some strange, deeply sinister, unconscious level, disguised as the unredeemably evil Emperor who, as so many people have remarked, seems modeled on the witch in Snow White (the heroine’s stepmother). Her male disguise makes it permissible to subject her to the most violent expulsion from the narrative yet. Read like this, Return of the Jedi becomes the Ordinary People of outer space, with Darth Vader as Donald Sutherland and Obi One and Yoda in tandem as the psychiatrist.

If the Star Wars films—like the overwhelming majority of 80s Hollywood movies—put women back where they belong (subordinate or nowhere), they do the same, in a casual, incidental way, for blacks and gays. The token black (Billy Dee Williams) is given a certain token autonomy and self-assertiveness, but he has a mere supporting role, in all senses of the term, on the right side, and raises no question of threat or revolution. Gays are handled more surreptitiously. Just as the 40s war movie generously included various ethnics in its platoon/bomber crew, so its 80s equivalent has its subordinate, subservient (and comic and timid) gay character, in the entirely unchallenging form of an asexual robot: CP-30, with his affected British accent, effeminate mannerisms, and harmlessly pedophile relationship with R2D2 (after all, what can robots do?). On the other hand, there is the Star Wars rendering of a gay bar, the clientele exclusively male, and all grotesque freaks.

Thus the project of the Star Wars films and related works is to put everyone back in his/her place, reconstruct us as dependent children, and reassure us that it will all come right in the end: trust Father.1

SPIELBERG AND E.T.

While it is in many respects permissible to speak of a Lucas-Spielberg syndrome—films catering to the desire for regression to infantilism, the doublethink phenomenon of pure fantasy—Spielberg and, especially, E. T. also demand some separate consideration. The Star Wars films are knowing concoctions, the level of personal involvement (that facility of invention that I have granted them) superficial. Raiders of the Lost Ark belongs with them, but with Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E. T. there is a certain sense of pressure, of personal necessity. Semiologists would call this the inscription of the author in the film; the popular response is to applaud Spielberg’s “sincerity.” However one takes it—as evidence of a genuine creative drive, or as simply one further level of signification—I am not arguing that it necessarily makes the films better than the Star Wars movies. Sincerity is a difficult concept (Spielberg’s, in conjunction with the films’ extraordinary efficiency, makes him a lot of money) and in itself carries no connotations of value; popularly, it tends to get confused with “giving us a nice feeling,” but logically there is no more reason to credit Spielberg with it than, say, Mickey Spillane, whose novels also carry a charge of personal investment, If the Spielberg films are in some ways more interesting than the Star Wars trilogy, it is because the personal investment has as its corollary, or perhaps its source, a certain disturbance; the sincerity seems in large part the need to cover over that disturbance, a personal need for reassurance (which the Star Wars films peddle as a commodity), the desire to “believe.” Another way of saying this is to suggest that the patriarchal/Oedipal trajectory is never quite as simple, direct or untroubled, and takes more curious and deviant routes, in the Spielberg movies. That the films fail to be more interesting than they are testifies to the success of the fantasy: the disturbance is covered over very effectively, almost obliterated. Illuminating comparisons might be made with two of E. T.’s thematic antecedents: Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People and Cohen’s It’s Alive movies.

One needs to distinguish carefully between the childlike and the childish (just as one needs to distinguish the true innocence of childhood from the sentimental, sanitized, desexualized version of bourgeois ideology). Peter Coveney’s admirable The Image of Childhood undertakes just such a distinction, examining the differences between the Romantic concept of the child (Blake, Wordsworth) as symbol of new growth and regeneration (of ourselves, of civilization) and the regressive Victorian sentimentalization of children as identification figures for “childish adults,” the use of the infantile as escape from an adult world perceived as irredeemably corrupt, or at least bewilderingly problematic.2 Both models persist, intermittently, in our culture: within the modern cinema, one might take as an exemplary reference point the Madlyn of Céline and Julie Go Boating and the multiple suggestions of growth and renewal she develops in relation to the four women of the film. Spielberg in E. T. seems to hesitate between the two concepts (Elliott’s freshness and energy are seen in relation to a generally oppressive civilization, though he is never Blake’s “fiend hid in a cloud”) before finally committing himself to the childish. If Spielberg is the ideal director for the 80s, it is because his “sincerity” (the one quality that the Star Wars films are vaguely felt to lack) expresses itself as an emotional investment in precisely that form of regression that appears to be so generally desired.

The attitude to the patriarchal family implicit in Spielberg’s films is somewhat curious. In Jaws the family is tense and precarious; in Close Encounters it disintegrates; in E. T. it has already broken up before the film begins. The first part of E. T. quite vividly depicts the oppressiveness of life in the nuclear family: incessant bickering, mean-mindedness, one-upmanship. This state of affairs is the result of the father’s defection, perhaps: the boys have no one to imitate, as Roy Scheider’s son in Jaws had. But he has defected only recently, and the Close Encounters family is scarcely any better. Yet Spielberg seems quite incapable of thinking beyond this: all he can do is reassert the “essential” goodness of family life in the face of all the evidence he himself provides. Hence the end of E. T. surreptitiously reconstructs the image of the nuclear family. Spielberg is sufficiently sophisticated to realize that he can’t bring Dad home from Mexico for a last-minute repentance and reunion (it would be too corny, not realistic, in a film that for all its status as pure fantasy has a great stake in the accumulated connotations of “real life”). But he produces a paternal scientist in Dad’s place (an even better father who can explicitly identify himself with Elliott—“When I was ten I was just like you,” or words to that effect). A climactic image groups him with mother and daughter in an archetypal family composition, like a posed photograph. For Spielberg it doesn’t really matter that the scientist has no intimate relationship with the mother, as his imagination is essentially presexual: it is enough that he stands in for Elliott’s missing father.

It follows that the position of women in Spielberg’s work is fairly ignominious. Largely denied any sexual presence, they function exclusively as wives and mothers (especially mothers), with no suggestion that they might reasonably want anything beyond that. The two women in Close Encounters typify the extremely limited possibilities. On the one hand there is the wife of Richard Dreyfuss (Teri Garr), whom the film severely criticizes for not standing staunchly by her husband even when his behavior suggests that he is clearly certifiable: she has to be dismissed from the narrative to leave him free to depart in the spaceship. On the other hand there is the mother (Melinda Dillon) whose sole objective is to regain her child (a male child, inevitably). No suggestion is made that she might go off in the spaceship, or even that she might want to. The end of E. T. offers the precise complement to this: the extraterrestrial transmits his wisdom and powers to the male child, Elliott, by applying a finger to his forehead, then instructs the little girl to “be good”: like Princess Leia, she will never inherit the Force.

As for men, Spielberg shows an intermittent desire to salute Mr. Middle America, which is not entirely incompatible with his basic project, given the way in which serious (read subversive) thought is repressed by the media: at the end of Jaws, Roy Scheider destroys the shark after both the proletarian and the intellectual have failed. By inclination, however, he gravitates toward the infantile, presexual male, a progression obviously completed by Elliott. (No one, of course, is really pre-sexual; yet the myth of the pre-sexuality of children remains dominant, and it is logical that the desire for regression to infantilism should incorporate this myth.) Roy Neary in Close Encounters is an interesting transitional figure. As he falls under the influence of the extraterrestrial forces his behavior becomes increasingly infantile (given the dirt he deposits all over the house, one might see him as regressing to the pre-toilet training period). Divested of the encumbrances of wife and family, he proceeds to erect a huge phallus in the living room; but, before he can achieve the actual revelation of its meaning, he must learn to slice off its top. As with the mother and the scientist of E. T. the film contradicts generic expectations by conspicuously not developing a sexual relationship, although Neary’s alliance with Melinda Dillon makes this more than feasible—generically speaking, almost obligatory. Instead, the symbolic castration makes possible the desexualized sublimation of the ending: Neary led into the spaceship by frail, little, asexual, childlike figures, to fly off with a display of bright lights the Smiths of Meet Me in St. Louis never dreamed of. The logical next step (leaving aside the equally regressive comic strip inanities of Raiders of the Lost Ark) is to a literal, but still necessarily male, child as hero.

Spielberg’s identification with Elliott (that there is virtually no distance whatever between character and director is clearly the source of the film’s seductive, suspect charm) makes possible the precise nature of the fantasy E. T. offers: not so much a child’s fantasy as an adult’s fantasy about childhood. It is also essentially a male fantasy: apart from Pauline Kael (whose feminist consciousness is so undeveloped one could barely describe it as embryonic), I know of no women who respond to the film the way so many men do (though not without embarrassment), as, in Kael’s term, a “bliss-out.” The film caters to the wish—practically universal, within our culture—that what W. B. Yeats so evocatively called “the ignominy of boyhood” might have been a little less ignominious. It is the fulfillment of this wish that most male adults find so irresistible. It is however, always worth examining what precisely it is that we have failed to resist. The film does for the problems of childhood exactly what Spielberg’s contribution to Twilight Zone did for the problem of old age: it raises them in order to dissolve them in fantasy, so that we are lulled into feeling they never really existed. Meanwhile boyhood (not to mention girlhood) remains, within the patriarchal nuclear family, as ignominious as ever.

Such a view of family life, male/female relations, and compensatory fantasy is obviously quite curious and idiosyncratic, always verging on the exposure of contradictions that only the intensity of the commitment to fantasy conceals. The essential flimsiness and vulnerability of the fantasy are suggested by the instability of E. T. himself as a realized presence in the film. Were it not for Spielberg’s sincerity (a sincerity unaccompanied by anything one might reasonably term intelligence, and in fact incompatible with it)—his evident investment in the fantasy—one might describe the use of E. T. as shamelessly opportunistic. From scene to scene, almost moment to moment, he represents whatever is convenient to Spielberg, and to Elliott: helpless/potent, mental defective/intellectual giant, child figure/father figure.

The film’s central theme is clearly the acceptance of Otherness (that specter that haunts, and must continue to haunt, patriarchal bourgeois society)—by Elliott, initially, then by his siblings, eventually by his mother, by the benevolent scientist, by the schoolboys. On the surface level—“E. T.” as an e. t.—this seems quite negligible, a nonissue. This is not to assert that there are no such things as extraterrestrials, but simply that, as yet, they haven’t constituted a serious social problem. They have a habit of turning up at convenient moments in modern history: in the 50s, with the cold war and the fear of Communist infiltration, everyone saw hostile flying saucers, and Hollywood duly produced movies about them; at a period when (in the aftermath of Vietnam and Watergate, and with a new Vietnam in Central America hovering over American heads) we need reassurance, Hollywood produces nice extraterrestrials. (The 50s produced some benevolent ones, too—It Came from Outer Space, for example—but they proved less profitable; contrariwise, the hostile, totally intractable kind are still with us—witness Carpenter’s The Thing, released almost simultaneously with E. T.—but the model is definitely not popular.)

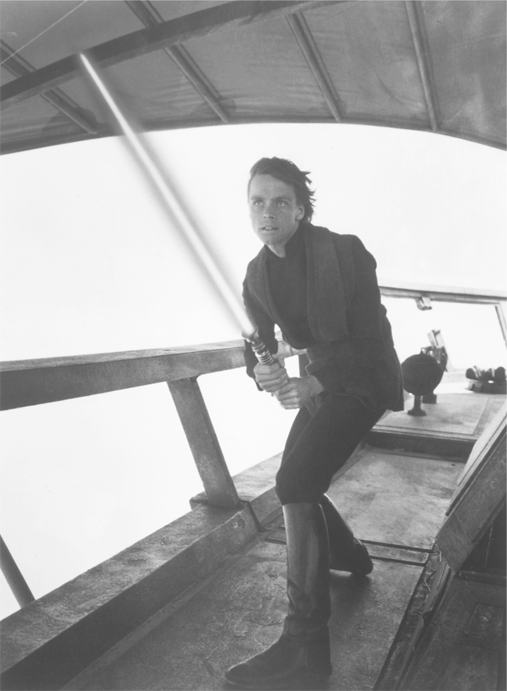

Spielberg’s Children

Cary Guffey with Melinda Dillon in Close Encounters of the Third Kind

Henry Thomas in E. T.

Unfortunately, on a less literal level, as a more general representation of Otherness, E. T. almost totally lacks resonance (“zero charisma,” one might say). All the Others of white patriarchal bourgeois culture—workers, women, gays, blacks—are in various ways threatening, and their very existence represents a demand that society transform itself. E. T. isn’t threatening at all: in fact, he’s just about as cute as a little rubber Martian could be. This, it seems to me, is what makes the film (for all its charm, for all the sincerity) in the last resort irredeemably smug: a nation that was founded on the denial of Otherness now—after radical feminism, after gay liberation, after black militancy—complacently produces a film in which Otherness is something we can all love and cuddle and cry over, without unduly disturbing the nuclear family and the American Way of Life. E. T. is one of us; he just looks a bit funny.

Poltergeist requires a brief postscript here. It is tempting to dismiss it simply as Tobe Hooper’s worst film, but it clearly belongs to the Spielberg oeuvre rather than to Hooper’s. Its interest and the particular brand of reassurances it offers both lie in its relation to the 70s family horror film—in the way in which Spielberg enlists the genre’s potential radicalism and perverts it into 80s conservatism. One can discern two parallel and closely related projects: First, the attempt (already familiar from Jaws) to separate the American family from “bad” capitalism, to pretend the two are without connection: there are a few greedy people, putting profit before human concerns, who bring on catastrophes, whether by keeping open dangerous beaches or not removing the bodies before converting cemeteries into housing developments. The project has a long history in the American cinema (its inherent tensions and contradictions wonderfully organized by Capra, for example, in It’s a Wonderful Life). With Spielberg it becomes reduced merely to a blatant example of what Barthes calls “inoculation,” where ideology acknowledges a minor, local, reformable evil in order to divert attention from the fundamental ones. Second, the attempt to absolve the American family from all responsibility for the horror. In short, a cleansing job: in the 70s, the monster was located within the family, perceived as its logical product. Poltergeist appears at first to be toying with this concept, before declaring the family innocent and locating the monstrous elsewhere: it is defined in terms of either meaningless superstition (corpses resent having swimming pools built over them) or some vague metaphysical concept of eternal evil (“the Beast”—superstition on a more grandiose scale), the two connected by the implication that the latter is evoked by, or is working through, the former. In any case, as in E. T., the suburban bourgeois nuclear family remains the best of all possible worlds, if only because any other is beyond Spielberg’s imagination. One might suggest that the overall development of the Hollywood cinema from the late 60s to the 80s is summed up in the movement from Romero’s use of the Star Spangled Banner (the flag) at the beginning of Night of the Living Dead to Spielberg’s use of it (the music) at the beginning of Poltergeist.

Blade Runner

Blade Runner was released in the United States simultaneously with E. T. and for one week was its serious challenger at the box office; then receipts for Blade Runner dropped disastrously while those for E. T. soared. The North American critical establishment was generally ecstatic about E. T. and cool or ambivalent about Blade Runner. E. T. was nominated for a great many Academy Awards and won a few; Blade Runner was nominated for a few and won none. I take these facts as representing a choice made in conjunction by critics and public, ratified by the Motion Picture Academy—a choice whose significance extends far beyond a mere preference for one film over another, expressing a preference for the reassuring over the disturbing, the reactionary over the progressive, the safe over the challenging, the childish over the adult, spectator passivity over spectator activity.

Admirers of the original novel (Philip Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) tend to regard the film with some hostility. But Blade Runner is not really an adaptation: rather, the film is built upon certain ideas and motifs selected from the novel. Its aim, argument and tone are so different that it is best to regard it as an autonomous work. Gone or played down are most of the novel’s major structuring premises: the nuclear war that has rendered the earth unsafe for the support of life and health; the use of animals as rare, expensive, coveted status symbols; the pseudoreligion of “Mercerism.” One might define the fundamental difference thus: the concerns of the novel are predominantly metaphysical, those of the film predominantly social. Some of the features discussed here derive (in most cases rather loosely) from the book; others do not. They are so well integrated that it seems unnecessary to spell out the distinction in each individual case.

Jobeth Williams in Poltergeist

Fantasy, by and large, can be used in two ways—as a means of escaping from contemporary reality, or as a means of illuminating it. Against the Spielbergian complacency of E. T. can be set Blade Runner’s vision of capitalism, which is projected into the future, yet intended to be clearly recognizable. It is important that the novel’s explanation of the state of the world (the nuclear war) is withheld from the film: the effect is to lay the blame on capitalism directly. The society we see is our own writ large, its present excesses carried to their logical extremes: power and money controlled by even fewer, in even larger monopolies; worse poverty, squalor, degradation; racial oppression; a polluted planet, from which those who can emigrate to other worlds. The film opposes to Marx’s view of inevitable collapse a chilling vision of capitalism hanging on, by the maintenance of power and oppression, in the midst of an essentially disintegrated civilization.

The depiction of the role played in this maintenance by the media is a masterly example of the kind of clarification—a complex idea compressed into a single image—advocated by Brecht: the mystified poor are mostly Asians; the ideal image they are given, therefore, dominating the city in neon lights, is that of a beautiful, richly dressed, exquisitely made-up female oriental, connected in the film (directly or indirectly) with emigration, Coca-Cola and pill-popping, various forms of consumption, pacification and flight.

The central interest of the film lies in the relationship between the hero, Deckard, and the “replicants”; the hero, one might add, is interesting only in relation to the replicants. The relationship is strange, elusive, multi-leveled, inadequately worked out (the failure of the film is as striking as its evident successes): the meeting of Raymond Chandler and William Blake is not exactly unproblematic. The private eye/film noir aspect of the movie is strongly underlined by Deckard’s voice-over narration, demanded by the studio after the film’s completion because someone felt that audiences would have difficulty in following the narrative (justifiably, alas: our own conditioning by the contemporary media is centered on, and continually reinforces, the assumption that we are either unable or unwilling to do any work). But that aspect is clearly there already in the film, which draws not only on the Chandler ethos but also on the rethinking of it in 70s cinema (Altman’s The Long Goodbye, more impressively Penn’s Night Moves): the moral position of Chandler’s knight walking the “mean streets” can no longer be regarded as uncompromised. Deckard’s position as hero is compromised, above all, by the way the film draws upon another figure of film noir (and much before it), the figure of the double—which brings us to the replicants.

If Blade Runner’s attitude to American capitalism is at the opposite pole to Spielberg’s, the logical corollary is that the film’s representation of the Other is at the opposite pole to that of E. T., though without falling into the alternative trap embodied by Carpenter’s “Thing.” The replicants (I am thinking especially of Roy and Pris) are dangerous but fascinating, frightening but beautiful, other but not totally and intractably alien; they gradually emerge as the film’s true emotional center, and certainly represent its finest achievement. Their impressiveness depends partly on their striking visual presence, but more on the multiple connotations they accrue as the film proceeds, through processes of suggestion, association, and reference.

The central, defining one is that established by the near-quotation from Blake with which Roy Batty introduces himself (it has no equivalent in the novel):

Fiery the angels fell; deep thunder rolled

Around their shores, burning with the fires

of Orc (America: A Prophecy, lines 115–16)

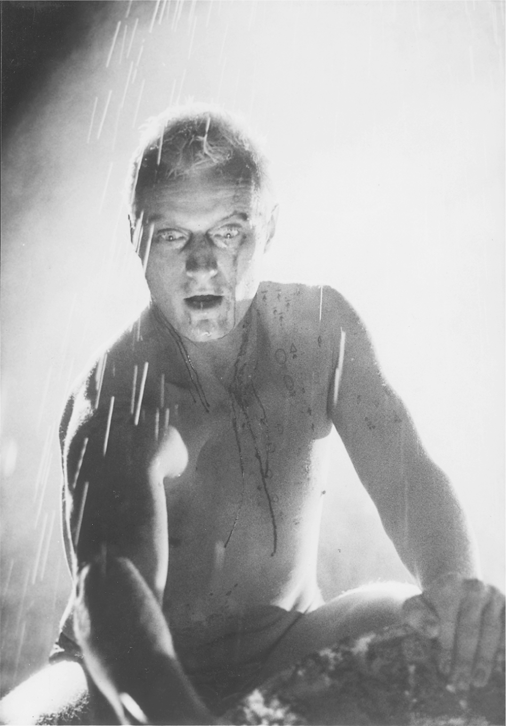

Blake’s poem is a celebration of the American Revolution, a narrative about the founding of modern America, interpreted on a spiritual/symbolic plane. Orc leads the revolt against oppression; he is one of Blake’s devil-angels, descendant of Milton’s Lucifer as reinterpreted by Blake (“Milton was of the devil’s party without knowing it”), the spirit of freedom, “Lover of wild rebellion and transgression of God’s law,” consistently associated with fire (“the fiery joy”). Roy, however, misquotes: Blake’s original reads “Fiery the angels rose,” the rising of the angels signifying the beginning of the revolt which is to found the free democratic state that, two hundred years ago, could be viewed idealistically as a step in humanity’s progress toward the New Jerusalem. The change from “rose” to “fell” must be read, then, in terms of the end of the American democratic principle of freedom, its ultimate failure: the shot that introduces Roy, the rebel angel, links him in a single camera movement to the imagery of urban squalor and disintegration through which he is moving. Clearly, in the context of 80s Hollywood, such an implication could be suggested only in secret, concealed in a particularly esoteric reference. Subsequently, Roy’s identification with the Blake revolutionary hero is rendered visually: stripped to the waist for the final combat with Deckard, he could have stepped straight out of one of Blake’s visionary paintings.

The other connotations are less insistent, more a matter of suggestion, but (grouping themselves around the allusion to Blake) they add up to a remarkably complex and comprehensive definition of the Other. First, the replicants are identified as an oppressed and exploited proletariat: produced to serve their capitalist masters, they are discarded when their usefulness is over and “retired” (i.e., destroyed) when they rebel against such usage. Roy tells Deckard: “Quite an experience to live in fear. That’s what it is to be a slave.” They are also associated with racial minorities: when Deckard’s boss refers to them by the slang term “skin-jobs,” Deckard immediately connects this to the term “niggers.” Retaining a certain sexual mystery, they carry suggestions of sexual ambiguity: Rachael’s response to one of Deckard’s questions in the interrogation scene is “Are you trying to find out if I’m a replicant or if I’m a lesbian?”; the climactic Roy/Deckard battle accumulates marked homoerotic overtones (made explicit in Roy’s challenge “You’d better get it up”), culminating in his decision to save Deckard’s life. The replicants have no families: they have not been through the bourgeois patriarchal process known euphemistically as socialization. They appear to be of two kinds—those who are not supposed to know they are replicants (Rachael) and have accordingly been supplied with “memory banks,” false family photographs, etc., and who are therefore more amenable to socialization, and those who know they are other (Roy/Pris) and live by that knowledge. Roy and Pris are also associated with childhood, not only by the fact that they are literally only four years old, but by their juxtaposition with the toys in J. F. Sebastian’s apartment, an environment in which they are so at home that Pris can be assimilated into it, becoming one of Sebastian’s creations when she hides from Deckard. Pris, made up as a living doll, irresistibly evokes punk and the youth rebellion associated with it. As in Blake, the revolution is ultimately against the Father, the symbolic figure of authority, oppression and denial (“Thou shalt not”); it is therefore appropriate that the film should move toward Roy’s murder of Tyrell, his creator, owner, and potential destroyer.

Blake’s Rebel Angel: Rutger Hauer in Blade Runner

The parallels that seek to establish Roy as Deckard’s double are fairly systematic but not entirely convincing, the problem lying partly in the incompatibility of the film’s literary sources (Philip Marlowe can scarcely look into the mirror and see Orc as his reflection). Rachael’s question (never answered) “Did you ever take that test yourself?” suggests that Deckard could be a replicant; Deckard’s own line, “Replicants weren’t supposed to have feelings, neither were blade runners,” develops the parallel. The crosscutting in the battle with Roy repeatedly emphasizes the idea of the mirror image with the injured hands, the cries of pain. The relationship is above all suggested in Roy’s contemptuously ironic “Aren’t you ‘the good man’?”: hero and villain change places, all moral certainties based upon the status quo collapse.

The more often I see Blade Runner the more I am impressed by its achievement and the more convinced of its failure. The problem may be that the central thrust of the film, the source of its energy, is too revolutionary to be permissible: it has to be compromised. The unsatisfactoriness comes to a head in the ludicrous, bathetic ending, apparently tacked on in desperation at the last minute. But how should the film end? In the absence of any clear information, two possibilities come to mind, the choice depending, one might say, on whether Philip Marlowe or Orc is to have the last word. The first scenario involves the film noir ending in which Rachael is retired by Deckard’s superior who is then killed in turn by Deckard (himself mortally wounded, perhaps) in a final gun battle. In the second, Deckard joins the replicant revolution. The former is probably too bleak for 80s Hollywood, the latter too explicitly subversive for any Hollywood. Either would, however, make some sense and would be the outcome of a logical progression within the film, whereas the ending we have makes no sense at all: Deckard and Rachael fly off to live happily ever after (where?—the film has clearly established that there is nowhere on earth to go). The problem partly lies in the added voice-over commentary, the only evidence we are given that Rachael has been constructed without a “determination date”: were she about to die, the notion of a last desperate fling in the wilderness would make slightly more sense, and we would not be left with the awkward question of how they are going to survive.

The film’s problems, however, are not confined to its last couple of minutes: just as its strengths are centered in the replicants, so too are its weaknesses. If Roy is the incarnation of the Blakean revolutionary hero, he also, especially in association with Pris, carries other connotations that are much more dubious, those of an Aryan master race. This is very strongly suggested by the characters’ physical attributes (blondness, beauty, immense strength), but it is also, more worryingly, signified in their ruthlessness: the offscreen murder of J. F. Sebastian (not in the novel) seems completely arbitrary and unmotivated, put in simply to discredit the replicants so that they cannot be mistaken for the film’s true heroes. The problem is rooted in the entire tradition of the Gothic, of horror literature and horror film: the problem of the positive monster, who, insofar as he becomes positive, ceases to be monstrous, hence no longer frightening. It is the problem that Cohen confronted in the It’s Alive movies (and failed to resolve in the second) and that Badham confronted in Dracula (a film that, like Blade Runner, develops disturbing Fascist overtones in its movement toward the monster’s rehabilitation).

The central problem, however, is Rachael and her progressive humanization. The notion of what is human is obviously very heavily weighted ideologically; here, it amounts to no more than becoming the traditional “good object,” the passive woman who willingly submits to the dominant male. What are we to make of the moment when, to save Deckard’s life, Rachael shoots a fellow replicant? Not, clearly, what other aspects of this confused movie might powerfully suggest: the tragic betrayal of her class and race.

The film is in fact defeated by the overwhelming legacy of classical narrative. It succumbs to one of its most firmly traditional and ideologically reactionary formulas: the elimination of the bad couple (Roy, Pris) in order to construct the good couple (Deckard, Rachael). The only important difference is that in classical narrative the good couple would then settle down (“I’ll take you home now”), whereas here they merely fly away to nowhere. Long ago, Stagecoach had its couple drive off, “saved from the blessings of civilization,” to start a farm over the border; The Chase was perhaps the first Hollywood film to acknowledge, ahead of its time, that there was no longer any home to go to. Seventeen years later, Blade Runner can manage no more than an empty repetition of this—with the added cynicism of presenting it as if it were a happy ending.

Blade Runner belongs with the incoherent texts of the 70s: it is either ten years behind its time or hopefully a few years ahead of it. If the human race survives, we may certainly hope to enter, soon, another era of militancy, protest, rage, disturbance, and radical questioning, in which context Blade Runner will appear quite at home.

Postscript 2003: Since this book was written, Ridley Scott’s original cut of Blade Runner has become available. There are three major differences, all improvements: the absurd “happy ending” has gone; the voiceover narration has been omitted; the suggestion that Deckard may himself be a replicant has been considerably strengthened. The film’s major problems, however, remain.

1. It is striking that, since this chapter was written, the essential ugliness of the 80s science fiction/comic strip project—hitherto concealed beneath the sweetness-and-light of patriarchal morality—has risen to the surface: witness the obsessive violence of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and the pervasively sick imagery of Gremlins (which Spielberg “presented”). Dune is the culmination of the exposure of rottenness. It is the most obscenely homophobic film I have ever seen, managing to associate with homosexuality in a single scene physical grossness, moral depravity, violence and disease. It shows no real interest in its bland young lovers or its last-minute divine revelation, all its energies being devoted to the expression of physical and sexual disgust. Much of the imagery strongly recalls David Lynch’s earlier Eraserhead, but the film seems only partly explicable in auteurist terms; the choice of Lynch as writer-director would also need to be explained, and the film must be seen in the wider context as a product of the 80s Hollywood machine.

2. It is peculiarly appropriate that a new version of Peter Pan should be among Spielberg’s current projects.