HOLLYWOOD FEMINISM: THE 70S

In order to be admitted to the Hollywood cinema at all, feminism had to undergo various drastic changes, the fundamental one, from which all the rest follow, being the repression of politics. In Hollywood films—even the most determinedly progressive—there is no “women’s movement”; there are only individual women who feel personally constrained.

Hollywood’s intermittent concern with social problems has, in fact, almost never produced radically subversive movies (and if so, then incidentally and inadvertently). A social problem, explicitly stated, must always be one that can be resolved within the existing system, i.e., patriarchal capitalism; the real problems, which can’t, can only be dramatized obliquely, and very likely unconsciously, within the entertainment movie. Just as Cruising can tell us far more about the relationship between patriarchy and homophobia than Making Love, so Looking for Mr. Goodbar can tell us far more about the oppression of women and the tensions inherent in contemporary heterosexual relations than An Unmarried Woman.

The two films generally singled out to represent Hollywood feminism are Paul Mazursky’s An Unmarried Woman and Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. It seems superfluous at this point to rehearse yet again their limitations. What seems not to have been noticed is that they share a common structure, in which those limitations are embodied. The significance of this—given that there are no tangible connections between the two films, in the form of common writers, producers, directors, stars, studios—should be obvious: the structure defines the limits of the ideologically acceptable, the limits that render feminism safe. It is with structure rather than texture that I shall be concerned here, so I shall preface the account by saying that Scorsese’s film seems to me not just the more immediately engaging (by virtue of that surface aliveness that is due, especially, to Scorsese’s work with actors) but the richer and more complex work, despite the fact that superficially it appears the more compromised, the heroine’s capitulation being more complete. Partly, this is bound up with its working-class milieu: it is simply too easy to make a film about the liberation of an upper-class career woman with a lucrative position in the fashionable art world. Scorsese’s film cannot resolve its problems satisfactorily, but at least it doesn’t so glibly evade them.

Ellen Burstyn in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore

With Diane Ladd

With Alfred Lutter

The common structure can be broken down into its main components (for the sake of brevity, I shall indicate variations on the pattern by the directors’ initials):

1. At the outset, the heroine is married (in M. apparently happily, in S. unhappily).

2. She has a child, signified as on the verge of or just into adolescence (M.: a daughter; S.: a son). Despite the gender difference, the resemblance is remarkable, the dominant characteristic being precocity. In both films the child is young enough to be still dependent; mature enough to be a semi-confidant, engaging with the mother in arguments and intimate exchanges; independent enough to demand his/her own rights. Hence, the child functions in both films as a problem, and simultaneously provides reassurance that the marriage breakdown isn’t irremediably damaging.

3. The marriage ends (M.: the husband leaves the heroine for another woman; S.: the husband is killed in an accident), and the woman has to make a new life for herself and the child.

4. The heroine is already (M.) or becomes (S.) involved in a group of women who provide emotional support (M.: Erica’s friends; S.: the other waitresses). The development of Alice’s mutually supportive relationship with Flo is among the most positive and touching things in Scorsese’s film.

5. The heroine has an unsuccessful and transitory relationship with an unsatisfactory lover (M.: because he is promiscuous and rejects commitment; S.: because he is psychotic and already married). Harvey Keitel, in a generally atypical film, is in the direct line of descent of Scorsese’s male protagonists, complete with Scorpio pendant.

6. The heroine meanwhile pursues, or attempts to pursue, a career that satisfies her need for self-respect (M.: successfully, as a receptionist in an art gallery; S.: unsuccessfully, as a singer).

7. In the course of her work, she meets a non-oppressive male to whom she can relate on equal terms and with whom she develops a satisfying, if troubled, relationship.

This last development—felt in both cases as the film’s necessary culmination—is obviously crucial. It occurs roughly two-thirds of the way through, and represents the end of the heroine’s trajectory; both men (M.: Alan Bates; S.: Kris Kristofferson), despite the fact that one is an artist and the other a rancher, are strikingly similar in type: burly, bearded, emphatically masculine, physically strong, and emotionally stable: reassuring, not only for the woman in the film, but for women in the audience and—perhaps most important of all—for men in the audience. The films share a certain deviousness. On the explicit level, both preserve a determined ambiguity, refusing to guarantee the permanence of the happy ending. Yet the final effect is of a huge communal sigh of relief: the women don’t have to be independent after all; there are strong, protective males to look after them. Their demand for independence is accordingly reduced to a token gesture, becoming little more than an irrational “feminine” whim. The “nonoppressiveness” and the “equality,” though heavily signaled, are also extremely problematic, existing purely on the personal level in terms of sympathetic individual men and never clearly examined in terms of social positions. Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, with its richer generic background, develops a particular irony here, although it is never brought to a sharp focus: the Western traditionally offered women two options, the rancher’s wife or the saloon entertainer; they remain, in a consciously feminist film of 1974, precisely the options open to Alice.

In a brilliant article in the 1983 Socialist Register (“Masculine Dominance and the State”), Varda Burstyn distinguishes between women’s liberation and women’s equality:

The notion of equality for women rather than the notion of women’s liberation denies a transformative dynamic to women’s struggles …. It implicitly but firmly sets the lifeways and goals of masculine existence as the standards to which women should aspire and against which official estimates of their “progress” will be made. It poses the problem as one of the women’s “catching up to men,” rather than as a problem for women and men to solve together by changing the conditions and relations of their shared lives—from their intimate to their large-scale social interaction.

What Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and An Unmarried Woman offer is, at best, equality, not liberation, and even the equality is precarious and compromised.

HOLLYWOOD ANTIFEMINISM: THE 80S

The precariousness of what was achieved in the 70s can be gauged from the ease with which it has been overthrown in the 80s. The pervasiveness of antifeminism in current Hollywood cinema (it is seldom of course explicitly presented as such, and often embodied merely in the reinstatement of traditional role models, as if nothing had happened) has been noted elsewhere in this book. Here I want to focus simply on two pairs of parallel examples, one from the beginning of the period and one representing the subsequent, more brazen development of the implications. The examples are offered as representative: if they stand out, it is only by virtue of their clarity.

Urban Cowboy and Bronco Billy were released almost simultaneously in 1980. The dramatic tension in both is centered on the efforts of an active, even aggressive woman to assert herself within a strongly male-dominated environment, in activities associated with masculinity: Debra Winger proves that she can ride the mechanical bull at least as well as John Travolta; Sondra Locke proves herself at least as good a sharp-shooter as Clint Eastwood. The narrative then moves to the point, where the woman comes to understand that she isn’t happy with this “equality”: Debra Winger realizes that what she’s really wanted all along is to wash her husband’s socks; Sondra Locke ends up spreadeagled on a revolving wheel, as Bronco Billy’s target in his traveling Wild West show. Both films, though contemporary in setting, explicitly locate themselves in the tradition of the Western, and use this as a means of putting assertive women back where they belong—respectively, as wife and object-of-the-gaze; both narratives teach the woman to be fully complicit in her own oppression. One must also note the uncomprehending vacuity of the underlying premise: the principles of feminism reduced to the demand to participate in the violent rites of masculinity.

Two of the ugliest moments in recent Hollywood films occur in An Officer and a Gentlemen and in Terms of Endearment. In the first, Debra Winger turns on her friend and denounces her for having pretended to be pregnant in order to trap a man into marriage (“God help you”). In the second, Debra Winger turns on a group of her New York acquaintances and denounces them for their divorces, abortions, etc. Both narratives are careful to justify the outburst dramatically: in the former, the feigned pregnancy has precipitated the lover’s suicide; in the latter, the New York friends are presented, stereotypically, as superficial, trendy and blasé. Yet again, the alibi of realism masks ideology: the insidious purpose of each film is to suggest that the only alternative for a woman to being a “good” wife/mother is to be duplicitous or fashionably desensitized.

The two moments have a good deal in common. Each occurs at roughly the same point in the narrative (about two-thirds through the film, around the point where the development of the relationship with the acceptable male occurred in the 70s movies), and marks a decisive step in its progression. Each uses a woman to denounce other women, the woman in both cases having come fully to accept her correct traditional role, even though both she and the film know that role to be fairly ignominious (affirmation in the 80s is never free of cynicism). In An Officer and a Gentleman this movement is used to support the film’s glorification of militarism, the ultimate embodiment of masculinity. Just what it supports in Terms of Endearment is less easy to define, though central to it is a mystique of motherhood—hence the emphasis on abortion—that has given the film an unfortunate credibility for many women (in combination with its maddening “great acting,” which amounts to no more than a relentless parade of knowing mannerisms). There is also, of course, the presence in both films of Debra Winger. One might say that Winger, having learned to oppress herself in Urban Cowboy, has gone on to dedicate her career to the oppression of other women. But that is perhaps putting it too personally. What is at issue is not Winger’s acting ability or even her presence as a personality (both could be inflected in various ways), but the star image that has been constructed around her: Winger-as-star has become the indispensable 80s woman, a major focus for the return to the good old values of patriarchal capitalism and the restoration of women to their rightful place.

It is a profoundly depressing and alienating experience to sit in a packed auditorium watching these films with an audience who actually cheer their grossest moments. Doubtless, at the end of the world, bourgeois society will sit dying among the ruins still congratulating itself on the rightness of its good old values: a spectacle literally enacted in Lynne Littman’s Testament.

DIRECTING WOMEN

The first great wave of feminism, around the turn of the century, coincided roughly with the invention of cinema; the second, through the 60s and 70s, produced an impressive body of critical/theoretial work and some distinguished avant-garde, “alternative” filmmaking. Neither, so far, has managed radically to affect the structures of mainstream film production (either the economic and power structures of an overwhelmingly patriarchal industry or the aesthetic and thematic structures of the films it turns out). It would be wrong, however, to assume that feminism has had no effect on Hollywood whatever. On the level of content it has provoked, negatively, a massive retaliation (ranging from the shameless grossness of the mad slasher movie to the far more insidious reinstatement of compliant women to their safe, traditional roles enacted in films like An Officer and a Gentleman and Terms of Endearment) that testifies at least to the magnitude of the threat; less negatively, if not entirely positively, feminism has aroused a pervasive sense of disturbance and unease. On the professional level, the grudging recognition that women can do the work of men (a superficial but not unimportant response to feminism) has made it somewhat less difficult, if by no means easy, for women to work as directors. During the past ten years or so we have seen more or less distinguished films by Elaine May (The Heartbreak Kid), Claudia Weill (Girl Friends), Joan Micklin Silver (Chilly Scenes of Winter), Jane Wagner (Moment by Moment), Lee Grant (Tell Me a Riddle), Amy Heckerling (Fast Times at Ridgemont High), Lynne Littman (Testament) and Barbra Streisand (Yentl), together with entirely negligible ones by Joan Rivers (Rabbit Test), Joan Darling (First Love), Nancy Walker (Can’t Stop the Music), Barbara Peeters (Humanoids from the Deep) and Martha Coolidge (Joy of Sex). I have not seen Anne Bancroft’s Fatso. In terms of numbers, the tally is unprecedented in any previous period, though of course still enormously outweighed by the films made by men.

The continuing inequality between the sexes can be measured not only in numbers but in terms of the conditions under which women are permitted to make films (and that word “permitted,” deliberately chosen, speaks volumes). Ten of the fourteen in the above list have made, at time of writing, only one commercial theatrical movie, though Heckerling is currently working on a second;1 six of the fourteen established themselves as performers first (a route proportionately uncommon for men); none has so far managed to establish a stable, continuous career (May, with three films, has not directed since 1974; Silver, also with three, not since 1979; Weill, with two, not since 1980). One may ask why no woman (Streisand the partial exception) has ever made a really big-grossing box office hit. Treating the possible sexist response with the contempt it deserves, one may suggest that one reason is that no woman (Streisand again excepted) has been entrusted with the kind of material from which box office hits ore made: the projects that women directors have been able to set up are, typically, modest, low-budget affairs on unassuming subjects, usually without major stars. During the Classical Hollywood period, Dorothy Arzner (20s to 40s), working intermittently with major female stars (Hepburn, Crawford), was able to build an impressively solid body of films, but always on projects regarded by the studios as minor and feminine, which came to the same thing. Ida Lupino (again an established star before becoming a director) made half-a-dozen films in the 50s, all B movies on restricted budgets. Stephanie Rothman, courageously plunging into the exploitation field of beach parties, horror, violence and sex, practiced some remarkable, though not widely celebrated, strategies of subversion in the 60s and early 70s, and has been unable to set up a film since, though still eager and certainly able.

So much for statistics. The problems they indicate go far beyond what might seem the simple, obvious explanation that men continue to resent women in positions of power—which is not to deny that that explanation carries a lot of weight. The male aversion seems to be primarily a practical one: less objection exists to women’s power behind the scenes, as screenwriters or producers; the aversion is to women’s power made visible and concrete. An obvious parallel: there are very few female orchestral conductors, and no very famous ones. A woman can be a pianist or violinist of international status (and presumably Cécile Ousset and Kyung-Wha Chung, when they play concertos, determine the tempi and overall conception), but she cannot stand up in front of an orchestra composed mainly of males and be seen to direct and dominate them. I have heard wonderful broadcast concerts by the Milwaukee Symphony under Margaret Hawkins, but Ms. Hawkins, as far as I know, never leaves Milwaukee for the international tours taken for granted by her male, and often inferior, jet-setting counterparts.

The deeper problem can be suggested through a series of questions: What films might women of integrity want to make? If no woman has made an overwhelming box office smash, may this be because no woman in her senses would want to make Raiders of the Lost Ark, An Officer and a Gentleman, or Return of the Jedi? Entrusted with such projects, what could a woman director decently do but struggle to subvert them? Their commercial success is intimately bound up with their flattering of patriarchy. What possibilities exist for a female (not necessarily feminist) discourse to be articulated within a patriarchal industry through narrative conventions and genres developed by and for a male-dominated culture? The closure of classical narrative (of which the Hollywood happy ending is a typical form) enacts the restoration of patriarchal order; the transgressing woman is either forgiven and subordinated to that order, or punished, usually by death. The seminal writings of Claire Johnston and Pam Cook on Dorothy Arzner suggest that Arzner’s intervention in patriarchal projects could do little to alter the course of such narrative conventions; what it could do was to create disturbances and imbalances, rendering the happy ending problematic or unsatisfying. In effect, the films are being praised for their incoherence, their unresolved contradictions, their tendency to leave audiences dissatisfied—scarcely a recommendation within a commercially motivated industry (try going to a producer with “I’ve got this great idea for a really incoherent movie”).

I shall consider here some of the genuinely distinguished achievements of women directors in the past decade (especially Grant, Weill, Silver, and Heckerling). First, however, it seems fitting to focus briefly on Yentl, because it provides apparent answers to some of the problems. It is a big-budget production obviously intended to have wide popular appeal, directed, co-produced, and co-written by a woman as her own cherished project, on an explicitly feminist theme (a woman’s rebellion against patriarchal constraints), quite free of any of the obvious symptoms of incoherence (awkwardness, tentativeness, strain, imbalance, working against the grain). Yet—while a generally agreeable entertainment with a few wonderful moments—Yentl is really the answer to nothing. It is scarcely a breakthrough for women directors, as its existence is entirely dependent on Streisand’s status as Superstar. Its precise nature seems determined by her desire to give her audiences what they expect of her: there was a neat, sharp little ninety-minute movie there somewhere, but it has become almost submerged in lush production values (Sound of Music meets Fiddler on the Roof) and an inordinate number of songs as undistinguished as they are superfluous. Apart perhaps from some interesting if equivocal play with gender roles and sexual ambiguity, the film offers no challenge to anyone: its feminist theme is placed in the context of a culture so remote from our own that we can view it with a complacent sense of “how things used to be,” a sense confirmed by the ending, where Yentl emigrates to America and emancipation. As for the film’s coherence, it is precisely that of classical narrative, left completely undisturbed: the exceptional individual (Young Mr. Lincoln, Shane, Yentl) leaves a society too narrow to contain her/him, but only after ensuring the continuance of the patriarchal order through the reconstitution of the family or the couple. The general sense the film communicates of unearned self-congratulation calls to mind the slogan on the notorious advertisement for Virginia Slims: “You’ve come a long way, baby.” For truly progressive work by women in mainstream cinema we must look elsewhere.

FOUR FILMS

It will be clear from the works I discuss (Claudia Weill’s Girl Friends, Lee Grant’s Tell Me a Riddle, Joan Micklin Silver’s Chilly Scenes of Winter, and Amy Heckerling’s Fast Times at Ridgemont High) that I am using the term “mainstream” somewhat loosely. Of the four, the first two were produced independently on the margins of the industry, and would never have been made but for the pertinacity of the filmmakers; only the last belongs squarely within the contemporary development of Hollywood genres and cycles. I use the term solely to distinguish fictional feature films intended to reach general audiences from experimental or avant-garde work produced without expectation of widespread distribution and standing resolutely apart from anything that could reasonably be called “entertainment.” Many feminist critics have argued persuasively that the language (what one might call the organization of the look, both within the film and of the spectator) of mainstream cinema was developed by patriarchy for patriarchy and must be rigorously rejected; certain feminist filmmakers have put that argument into practice (the Laura Mulvey/Peter Wollen Riddles of the Sphinx is among the most impressive examples). Yet it seems to me desirable that all avenues be kept open, that the widest range of strategies and practices be attempted; it remains unproven that the patriarchal language of mainstream narrative film cannot be transformed and redeemed, that a woman’s discourse cannot speak through it. The four films on which I here offer brief notes (each deserves detailed attention) provide some evidence to the contrary.

It is significant that only the two independent movies embody overtly feminist projects, and even they never manage to acknowledge the existence of a political women’s movement: the obligatory conditions for a woman working for a major studio would appear to be discretion, subterfuge, deviousness, and compromise. Girl Friends is the only American commercial movie I can think of that explicitly calls marriage as an institution into question, as opposed to admitting that there are unsuccessful marriages, though a number of mainstream Hollywood movies (von Sternberg’s Blonde Venus, Sirk’s There’s Always Tomorrow, Cukor’s Rich and Famous—which owes a lot to Girl Friends) can be read as suggesting this implicitly, under cover of being “just entertainment.” Tell Me a Riddle is the only commercial American movie I can think of that explicitly parallels feminism and socialist revolution (though somewhat tactfully). Why should major studios, which are patriarchal capitalist structures from top to bottom, be expected to finance films that call into question their very premises? It is surprising enough that they agreed to distribute them. A culture committed to freedom of speech but built on money and private enterprise has a very simple means of repressing the former by using the latter, with no inconvenient or disturbing sense of hypocrisy. Girl Friends presents marriage as patriarchy’s means of containing and separating women: the friendship of the title is effectively destroyed by the marriage of one of the women, whose priorities then necessarily become her house, her husband, her child. The view of marriage in Tell Me a Riddle, though less negative, is not entirely dissimilar. Here, the husband feels threatened, not by a female friendship, but by the woman’s intellectual interests and revolutionary sympathies—in both cases, but in different ways, by the possibility of her autonomy. What is unique, and deeply moving, about Grant’s film is its generosity in allowing the husband to recognize, though much too late, the destruction his attitude has caused: the scene of marital reconciliation is among the great moments in modern American cinema, not least because it triumphantly breaks another taboo by permitting old people erotic contact.

The independence of these two films is as much a matter of narrative/thematic content as of production setup. Neither fits comfortably into traditional generic expectations. Girl Friends, predominantly comic in tone but taking up the themes (marriage vs. career, etc.) of the “woman’s melodrama,” ends on a note of regret at the formation of the heterosexual couple rather than the traditional glow of relief and satisfaction; Tell Me a Riddle continues beyond the reconciliation scene to the old woman’s death, the husband’s remorse at lost opportunities, the younger woman’s confirmed independence. The latter film, especially, is an extremely unorthodox project even aside from its feminist thrust: one of a very small handful of commercial films from any country on the highly uncommercial subject of old age.2

The achievement of Chilly Scenes of Winter and Fast Times at Ridgemont High, by contrast, can really only be appreciated in relation to the generic expectations and formulae they at once part fulfill, part undermine. Chilly Scenes is one of the very few woman-directed films centered on a male consciousness (men have never hesitated to make films centered on women, whereas women are always assigned or permitted feminine projects): an interesting strategy for the indirect expression of a woman’s discourse.

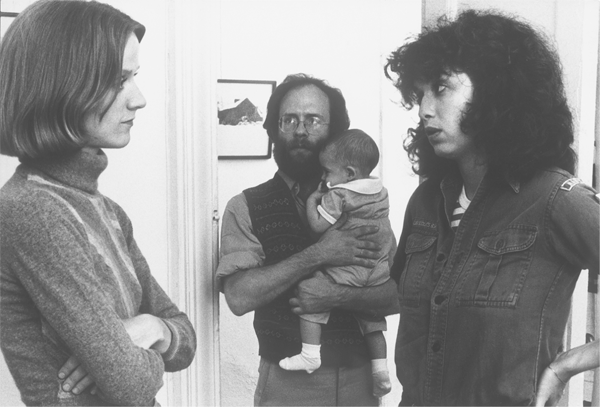

Marriage vs. Women’s Solidarity: Anita Skinner, Bob Balaban, and Melanie Mayron in Girl Friends

Undermining the Comic Stereotype: Gloria Grahame and John Heard in Chilly Scenes of Winter

The relationship of the film to Ann Beattie’s novel is complex, balancing fidelity with subtle transformation. Silver, who wrote the screenplay as well as directing the film, retains Beattie’s premise, plot, and characters (realized with wonderful delicacy and precision by the actors), adding inventions of her own (some of the flashbacks, Charles’ construction of the model of Laura’s house, his visit with Sam to the actual house, hence the entire scene with Laura and her husband) that are perfectly compatible with the original but give Beattie’s somewhat tenuous narrative, with its frequent recourse to internal monologues, a more concrete dramatization. Much of the dialogue is taken from the book, the film preserving the quality of its oblique, offbeat humor. However, the spirit of the book is subtly transformed. The transformation is due partly to the fact that the film owes as much to Hollywood—to a specific Hollywood tradition—as to its literary source. Its essence can be made clear by comparing Beatties’s and Silver’s endings. To put it succinctly, where Beattie gives us an unhappy happy ending, Silver substitutes a happy unhappy ending. (I am discounting here the ending that was tacked on to the film for its initial release, when its title was also changed to Head Over Heels.) At the end of the novel, the lovers get back together, yet it is clear that Laura has merely given up the struggle and is now wearily acquiescing to the insistence of Charles’ romantic (and thoroughly possessive) passion for her: nothing has changed, neither has learned anything. The book’s highly idiosyncratic and engaging humor becomes complicit in its defeatism: as people are incapable of growth or change, there is really nothing to do but laugh sadly and ironically at their predicament. Silver’s film ends with the lovers separated and with Charles at last finding himself able to accept the separation: each has learned to recognize, slowly and painfully, the oppressiveness of romantic possession/dependence. It is perhaps the first Hollywood film where the happy ending consists, not in the lovers’ union, but in their relinquishing its possibility.

The genre to which Chilly Scenes relates is not exactly topical: essentially, it belongs to the type of light comedy that flourished in the 30s and now seems virtually a lost art. The closeness of the fit can be suggested by the simple expedient of recasting it. The male protagonist trying to regain the woman he loves would have been Cary Grant, with Irene Dunne opposite him once again; the alternative but impossible lovers—“dumb blonde” secretary, dull businessman—would have been Lucille Ball and (of course!) Ralph Bellamy, with Billie Burke as the hero’s comic-eccentric, scatterbrained mother. Once one has grasped the pattern, Silver’s subtle inflections of it become quite fascinating. Crucial to the operation is her refusal to take romantic love for granted as an unquestionable value, or to assume the happy ending as the hero’s inalienable right. Our classical prototype would have been what Stanley Cavell calls a “comedy of remarriage”: the final reunion of the estranged couple would have been guaranteed from the outset by the fact that they were husband and wife. But in Chilly Scenes the male protagonist is the other man, the husband the dull businessman, and the woman ultimately rejects them both. Silver’s handling of the comic female stereotypes (secretary, mother) is also idiosyncratic: if still comic, they are also disturbingly vulnerable, so that our laughter is made uneasy.

If I devote more space to Fast Times at Ridgemont High, it is not because I consider it a better film, but because it was made right in the mainstream of contemporary Hollywood production and because it belongs to a cycle one would never have expected a woman of intelligence and integrity to be able, or indeed want, to infiltrate. If Eyes of a Stranger proves that the terms of even the most apparently intractable generic formulae can be partially subverted (on the condition of meeting the demand that they also be partially fulfilled), the same can be argued far Amy Heckerling’s disarming and exhilarating movie.

The terms of the 80s high school cycle (the obvious touchstones are American Graffiti and Porky’s, respectively its pre-80s initiation and its most fully representative 80s manifestation) can be set forth quite succinctly:

1. Sex Even though school is the setting, the films at no point show the slightest interest in education (unless negatively, as a nuisance). The need to graduate may occasionally be an issue, but chiefly because it interferes with the real one. The cynicism (typical in general of our civilization, but especially a feature of the 80s) is total, and totally taken for granted; to the extent that reviewers never comment on it, one assumes they share it. There is never any hint of serious or reasoned rebellion against the educational system: education is a nuisance and a farce, yet somehow mysteriously necessary: one must study in order to graduate, and one must graduate in order to take one’s place within the adult society one despises. The only film I have seen (marginal to the cycle, as its leading characters are preadolescent) that allows its characters to express overt antagonism to the educational system is Ronald Maxwell’s Kidco: the objection is that school fails to teach children how to make money. Generally, the assumption is that teenagers could not possibly be interested in anything except sex, and it would be rather absurd to expect it (serious students are by definition “nerds”—though nerds need not be serious students). The films are at once a significant product and reinforcement of the commodification of sex in contemporary capitalist culture, most of the consumer products of which must be advertised and sold on their sexual appeal, blatant or subtle.

2. The Suppression of Parents Given that the teenagers of the films still live at home, the almost total absence of parents is rather remarkable. Peewee’s mother (in Porky’s) appears in one brief scene; Stacey’s mother (in Fast Times) appears in one shot; fathers are either absent altogether or, in the case of the violent macho father of Porky’s, so obviously monstrous as to be easily repudiated. Like education, parents are a mysteriously necessary evil, to be avoided whenever possible. Of course, what the films dare not suggest (they would instantly lose all their appeal) is that these teenagers will grow up—inevitably, given their total lack of political awareness—to be replicas of their parents. Like education, parents interfere actually or potentially with the pursuit of sex: the less they are present in the films, the better. They are, in fact, reduced to the ignominious role of supplying occasional suspense (can the son/daughter get away in time for the next sexual encounter?).

3. Multicharacter Movies The aim is to reach and satisfy as wide a youth audience as possible; there must, therefore, be a range of identification figures, and no minority group (with one significant exception) must be entirely neglected (though arranged within a careful hierarchy).

4. Hunter/Hunted Two male figures recur, with variations, often in close juxtaposition—the one (there are likely to be several) who “knows all about it” and the one who doesn’t. A central plot thread concerns the male virgin who has to “get laid.” With both figures, the innocent and the experienced, the basic pattern is the same: male as hunter, female as hunted, male as looker, female as looked-at. The initiation of the male virgin is clearly crucial: the emphasis is less on his desire to achieve a pleasure already experienced by his fellows than on his need to prove himself, to become a “real man”: Getting laid is the guarantee of masculinity/heterosexuality, the denial of a possibility that the films cannot even mention.

5. The Repression of Homosexuality There are no gay teenagers in America: such, at least, is the films’ implicit message.3 No surprise, of course. What is marginally more surprising is that the films never acknowledge the possibility of teenage homosexual behavior, despite the fact that this is widely recognized as a normal phase in the progress toward true normality (“normally abnormal” might put the attitude more precisely). The phenomenon is common enough to demand explanation, various of which have been given: adolescent boys need sexual outlets, and girls are not always (or are not perceived to be) readily available, so they take “second best”; adolescents need to experiment in order to reject the inferior form of sexuality for the superior; the onset of adult sexuality can be experienced as frightening, and many boys are intimidated by the implicit demands on their potency. All these explanations are variously homophobic in asserting the superiority of heterosexuality over homosexuality. The most logical explanation—which is not homophobic—is consistently repressed: that the phenomenon represents the final struggle of our innate bisexuality to find recognition, before it capitulates to the demands of normality, the nuclear family and the patriarchal order. The films’ often quite hysterical and obsessive emphasis on “getting laid” can be seen as an unconscious acknowledgment of the reality of the threat: though the adult world is treated with contempt, no serious challenge to normality can be countenanced.

By this point it will be clear that the syndrome I have described is shared by another, exactly contemporary and equally popular, cycle discussed in the previous chapter: the teenie-kill pic. The parallel development is intriguing, especially as the overall import of the two cycles is (superficially at least) quite opposite: in the high school movies promiscuity is generally indulged, in the teenie-kill pics it is ruthlessly punished. The opposition may be less total than it first appears (see, for example, the obsessive emphasis on castration in Porky’s). The cycles seem premised on a common assumption: that, despite all the lip service to female equality, it is still the male who decides what movie young heterosexual couples will go to. Audiences for both cycles have been (in my experience) predominantly male, with all-male groups quite common. Any satisfaction the films offer the female spectator seems at once marginal and perverse: she is invited to contemplate, as something at once funny and desperately important, male initiation rites; or she is invited to contemplate reiterated punishment for sexual pleasure, with a special emphasis on female pleasure. One can see well enough why young males conditioned by the ideological assumptions of our culture in its current phase should want to drag their compliant girlfriends along to participate in what are essentially male rituals of desire and guilt, part of the films’ function being the reinforcement of that compliance.

The relation of Fast Times at Ridgemont High to this syndrome is extremely complex. Clearly, there are certain bottom-line generic conditions that must be satisfied for such a film to get made at all (just as Eyes of a Stranger could not exist if it did not contain sequences in which women are terrorized and brutally murdered): here, heterosexism and the commodification of sex. In fact, the film’s treatment of adolescent sexuality is consistently enlightened and intelligent, but it is compelled to subscribe to the myth that sex is all teenagers ever think about, with all its consequent ramifications. “Packaging”—a term that encompasses all the purely commercial interests involved from conception to publicity—is crucial here: it is interesting that the last line of dialogue (“Awesome—totally awesome”), which in the film has nothing whatever to do with sexual activity, was lifted out of context and used as an advertising slogan.

Where Fast Times succeeds, against all reasonable expectations, is in constructing a position for the female spectator that is neither masochistic nor merely compliant. One may begin at the end where Heckerling, in a single simple gesture, quietly rectifies the sexism of American Graffiti. Lucas ended his film with captions succinctly synopsizing the destinies of his four male characters; the implication was that the females were either of no consequence or so dependent on the men as to have no destinies of their own. Heckerling repeats the device, but allows the women full equality. Nor is this a mere afterthought; rather, it concludes the logic of the entire film. Heckerling’s six main characters include four males and two females. Yet, if there is a character who takes precedence over the others, it is clearly Stacey (Jennifer Jason Leigh). Where the cycle as a whole is obsessed with male sexual desire and anxieties (the girls in Porky’s have no problems, and exist purely in relation to the bays, whose “needs” they either satisfy or frustrate), Fast Times allows its young women both desire and disturbance: see, for example, the delightful scene in which Linda (Phoebe Cates), with the aid of a carrot, instructs an anxious Stacey in the techniques of the “blow job.” And, as the women cease to be objects of the male gaze, their autonomous desire is used to express, not merely an appreciation of male beauty (“Did you see his cute little butt?”), but a critique of male presumption. When Stacey responds to her date’s “You look beautiful” with an enthusiastic “So do you,” the film immediately registers his discomfiture, and the reaction prepares us for his behavior in the ensuing scene of intercourse: he shows no concern for Stacey’s sexual pleasure and no awareness of her pain (she was a virgin). During it, Heckerling cuts in a shot from Stacey’s point-of-view: a graffito, “Surf Nazis,” scrawled on the wall above her.

Fast Times at Ridgemont High

Amy Heckerling directing Judge Reinhold

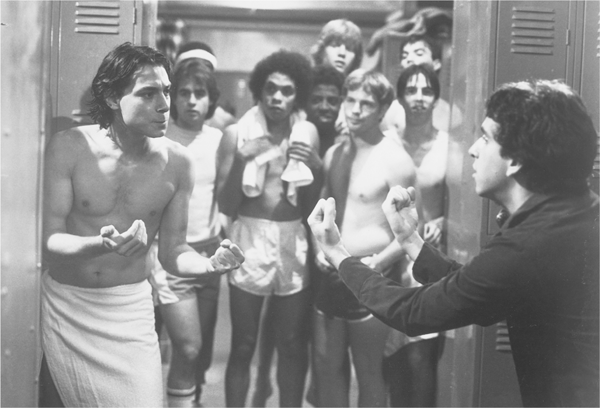

Male Confrontation: Robert Romanus and Brian Backer

Similar strategies characterize the treatment of Stacey’s brief relationship with Mike (Robert Romanus), the school lady-killer. It is she who takes the initiative, and the film suggests that this is what undermines him: he is accustomed to being the hunter. His sexual insecurity surfaces in the changing-cabin by Stacey’s family’s pool when Stacey asks, “You want to take off your clothes, Mike?’ and his automatic response (“You first”) is answered by her “Both of us at the same time”; he then “comes too soon.” Subsequently (before he learns that she is pregnant), he is too embarrassed to confront her, evading her friendly overtures: the film is clear that what is being “put down” is not sexual failure in itself, but the male vanity that makes so much of it.

The principle of rectifying the cycle’s sexist imbalance is not restricted to the development of the narrative; it determines the details of shooting and editing. This is established right at the outset, during the brilliantly precise and economical credits sequence: the second shot—Mike eyeing a girl—is answered instantly by the third, in which two girls eye Brad (Judge Reinhold). A little later, a traveling shot along a row of asses in tight jeans bent over pinball machines looks like a typical sexist cliché until one realizes that the asses are not identifiable as female. Two sequences are built upon the visual objectification of women; both are defined as male fantasies and are clearly placed by the context within which they occur. In one, Spicoli (Sean Penn) fantasizes his victory as surfing champion, a beautiful bikini-clad girl on each arm (the film elsewhere gives him no contact with real females whatever, defining his existence in terms of permanently doped amiability). The other is treated even more pointedly. Brad (Stacey’s brother), arriving home in the Captain Hook uniform of the fish restaurant where he works, finds Linda beside the pool and is embarrassed at being seen in a costume; he watches her from the washroom, fantasizes that she is offering herself to him, and begins to masturbate; entering the washroom without knocking, she catches him in the act.

The film takes up many of the cycle’s recurrent schemata but always uses them creatively. The economy of the various plot expositions depends upon the instant recognizability of the characters, but in every case the stereotype is resourcefully extended, varied or subverted. Especially interesting is the treatment of the male virgin, Mark (Brian Backer): the whole progression of his relationship with Stacey is built, not upon his desire to “get laid”—to become a “real man”—but on his continuing sexual reticence and diffidence, maintained beyond the ending of the film, where we are informed that he and Stacey are having a passionate love affair but still haven’t “gone all the way.” On the other hand the film, while firmly implying that the best relationships are based upon mutual respect and concern, is strikingly non-judgmental in its treatment of promiscuity and experimentation. It is also firmly “pro-choice”: abortion is certainly not presented as a pleasant experience, but neither is it treated as in the least shocking. The abortion episode is also used to establish what is otherwise conspicuously absent from the cycle, the positive potential of certain family ties, in Brad’s gentle, understanding, and nonpaternalist acceptance of his sister.

The film’s unobtrusive critique of male positions exists within the context of Heckerling’s generosity to all her characters, male and female alike. The film manages the extremely difficult feat of constructing a tenable position for the female spectator without threatening the male: this defines, one might say, both its success and its limitations. It is clearly impossible, in the current phase of social evolution, for a film that rigorously and radically explores the oppression of women to be nonthreatening. Fast Times must be seen as a reflection of current attitudes rather than a radical challenge to them; what it proves—a very rare phenomenon in contemporary Hollywood cinema—is that it is still possible to reflect (hence reinforce) the progressive tendencies in one’s culture, not merely the reactionary ones. Flawlessly played by a uniformly wonderful cast (Heckerling is obviously marvelous with actors), it restores a certain credibility to the concept of “entertainment.” Of the four films discussed Fast Times is predictably enough the only one that has had an appreciable box office success. It pays a price for this, of course. The other three women whose films I have considered are paying a different price: none is currently working on a theatrical feature film.

1. Johnny Dangerously has appeared just in time for a footnote which, alas, it barely deserves: Heckerling has allowed herself to be absorbed (temporarily, one hopes) into a comic mode that derives from TV (Saturday Night Live is the most obvious influence) in which a woman’s discourse is quite obliterated, and the film proves no more than that women can make movies that are just as bad as most of those made by men.

2. For a detailed analysis of Tell Me a Riddle, see the article by Florence Jacobowitz and Lori Spring in CineAction, no. 1.

3. Since this was written the curious and confused Revenge of the Nerds has supplied a gay college student. The film carefully compounds his otherness by making him black as well as gay and, in one disarming but not exactly uncompromised moment, equips him with a “limp-wristed javelin” with which to win a sporting event.