Our civilization’s great next step forward—if it is permitted one—will be the recognition and acceptance of constitutional bisexuality: an advance comparable to, and in certain respects more important than, the general acceptance of birth control. It had better be said at once that the reader who cannot entertain this proposition, at least as a working hypothesis, is going to have great difficulty with much of the remainder of this book.

Skeptics, however, might consider the logic of evolution, both in the biological/Darwinian sense and in the sense of social evolution. Homosexual choice begins with the primates. Rats, for example, indulge in homosexual activity only if deprived of access to the opposite sex; apes, on the other hand, can freely enjoy sexual activity with either sex. The implications of this are far-reaching. Before animals began to walk on their hind legs, the pleasure of sex was strictly contingent upon the need for procreation, for the continuance of the species. With creatures who walked upright (exposing and making openly accessible those parts of the body that the socialized human being is taught—and forced by law—to hide), the sexual instinct began to evolve into an end in itself, a means of pleasure and communication to which procreation became incidental. From the moment that principle is accepted, there is no logical reason why such a means of pleasure and communication should be restricted to members of the opposite sexes. Within social evolution, the acceptance of birth control implies precisely the same logic: a general recognition that the primary significance of sexuality lies in pleasure/communication, that procreation is a mere by-product that one can choose or not; therefore, that no logical reason remains why sexuality should be restricted to heterosexuality.

The logic that holds up heterosexuality as the norm is merely the perverted logic of patriarchy, that massive force that continues to impede the rightful progress of civilization and evolution. Patriarchy depends upon the separation of the sexes, hence upon the continued repression of bisexuality in order that masculinity and femininity may continue to be constructed. And the logical end result of the construction of masculinity (in terms of domination, aggression and competition) is nuclear war. The more immediate result—in the sense of being already a reality, not just a threat—is the extreme difficulty, for men whose femininity has been systematically repressed, of identifying with a female position, of bridging a gulf between the sexes that is itself ascribable to social construction rather than to nature. The phenomenon, discernible all around us and analyzable at virtually every point in contemporary mainstream cinema, is both the overall catastrophe of our civilization and the cause of innumerable personal tragedies.

This chapter will examine certain traces of repressed bisexuality that lurked (always ambiguously) in 70s Hollywood cinema, and will go on to consider the 80s films on explicitly gay themes that may seem, at first glance, to have brought those traces to the surface, but which may actually be the means of their obliteration. As a prelude, however, I want to digress briefly outside the proposed limits of this book, to consider, as exemplary of the tensions I have just defined, the work of Jean-Luc Godard. The justification for such a digression is simple: Godard, clearly one of the most important and most progressive filmmakers in the history of cinema, his work dedicated to a radicalism that, while varying in its specific allegiances, has remained uncompromisingly antagonistic to the norms of establishment society, achieving formal and political audacities and subversions that no one working in the Hollywood cinema has ever dared dream of, remains nonetheless trapped in the very same prison of masculinity that limits the work of a Scorsese or a Cimino, and that totally invalidates most of the remainder of contemporary Hollywood cinema. I want, in other words, to suggest that to be aesthetically and politically revolutionary carries no guarantee of exemption from the most obstinate, fundamental ideological constraints.

Godard’s early work, from Breathless to Pierrot le Fou, covering his first ten features, provides an interesting extension of Laura Mulvey’s famous thesis about the Hollywood action narrative, that the male protagonist (active, bearer of the look) carries forward the action while the woman (passive, the looked-at) repeatedly interrupts it, holds it up. The films centered on men (Breathless, Pierrot) are action films in which Godard clearly identifies with his male heroes (the women remain enigmas, potentially or actually treacherous, in the manner of film noir); those centered on women (Vivre So Vie, Une Femme Mariée) are sociological studies, in which the object of study is not so much prostitution, alienation, etc. as the woman herself.

Masculin, Féminin, which immediately followed Pierrot, is clearly a key work in Godard’s development. The male protagonist is split into two. Paul is a gentler version of Godard’s previous doomed drop-out heroes, seeking a “personal solution” in a relationship with a woman; with Robert, Godard introduces an explicit revolutionary political position into his work for the first time. It is Robert who tells Paul that a personal solution can’t work. At the end of the film Paul dies (in a kind of accidental suicide) and Robert survives—to go on to become the Maoist militants of La Chinoise and Vent d’Est.

Although, characteristically, Masculin, Féminin raises and interconnects a wide range of concerns, its title directs our attention clearly to sexual politics; it also seems to promise an equal weighting between the sexes, a promise that is not fulfilled. It is perhaps Godard’s most openly misogynistic film, the tentative commitment to revolutionary politics finding no counterpart on the level of heterosexual relations. The main plot line reproduces and reinforces the male myth of the sensitive, intelligent, vulnerable young man destroyed by the insensitive, egocentric, rather stupid woman (very disturbingly, this is carried over intact into Crystal Gazing, the film by those committed feminists Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen that is obviously in part a remake of Godard’s film). Women throughout are presented as essentially self-enclosed and unreachable. In the two extended scenes in which a male and a female character interview each other (Paul/Madeleine, Catherine/Robert), there seems to be some conscious attempt at equalizing the participants, but in both cases the balance is tipped, in obvious and subtle ways, in favor of the man. (Obvious: the male is permitted far more questions in both interviews, and far more screen time is devoted to his interrogation of the woman than to hers of him. Subtle: the women’s responses are in both cases partly discredited, Madeleine’s interview centering on the question of her “lying,” Catherine’s answers being evasive—like Eve, she eats an apple throughout.) The imbalance is confirmed by the long interview of “Miss Nineteen,” the one-sidedness of which is emphasized by the man’s remaining off-screen. The interview (apparently genuine, i.e., not acted) is one of the highlights of the film, a devastating exposure of the emotional and intellectual bankruptcy, the complacent unawareness, of this typical “consumer product” (as the film describes her) who is also a product of higher education. Yet important questions arise: Why this particular selection of women? Were there no intelligent, enlightened, politically aware young women available in Paris in 1966? (We are told, when she is introduced into the film, that Catherine is such, but nothing in her subsequent behavior or speeches supports the assertion.) Conversely, were there no unintelligent, self-enclosed, politically ignorant young men who might have been exposed to the merciless scrutiny of Godard’s questions and camera?

The starting point for Masculin, Féminin was Guy de Maupassant’s marvelous La Femme de Paul (which Ophuls had earlier wanted to use as the final story of Le Plaisir). What Godard does with his source is extremely illuminating. The lesbianism, both in the popular sexual sense and in the wider sense of women’s bonding together to resist male definition, that is so prominent and so positively treated in Maupassant’s story is all but suppressed in Masculin, Féminin: the traces of a lesbian involvement between Madeleine and Elizabeth are so fleeting and ambiguous that the spectator can be forgiven for missing them altogether. The film treats women’s bonding wholly negatively: in so far as it exists, it is seen entirely from Paul’s perspective, as a threat. It is significant that Elizabeth is virtually denied a voice: of the three female characters, she is the only one who is not interviewed. Even more significant—in view of the title’s suggestion of a balance between gender-positions—is the fact that the women are only fleetingly allowed a scene alone together (Catherine and Elizabeth briefly discussing sexuality), whereas Paul and Robert have extended scenes of intimate, though never, of course, physical, contact. Indeed, it might be said that only the two men are permitted intimacy in the film in any real sense of the word, the male/female confrontations being posited on the assumption of insurmountable barriers and possible scenes of female/female contact without male surveillance suppressed altogether.

One can argue that in Godard’s films as in dreams the seemingly inconsequential and irrelevant moments are in fact of particular significance. One such moment occurs in Masculin, Féminin. Paul, during the visit to the cinema, goes to the washroom and finds two men embracing in the cubicle; he then scrawls on the door “à bas la République des lâches” (“Down with the cowards of the Republic”). The moment (which appears to have nothing whatever to do with anything else in the film—one can certainly read it as an unconscious displacement of the lesbianism of La Femme de Paul) is ambiguous: the men may be cowards because they don’t come out and fight for their rights or make love in public, or simply because they are homosexuals (the heterosexual myth that a “real man” is defined by the ability and desire to possess women, on which Maupassant’s story can be read as an ironic commentary). The former meaning is merely uncharitable and irresponsible, taking no account of the social pressures that make the act of embracing in a public washroom in fact moderately heroic (this is, after all, 1966, when gay liberation and gay consciousness were scarcely in their infancy). I’m afraid, in the context of the whole film and of Godard’s work generally, one is forced to prefer the latter reading, far more reactionary and reprehensible. A fairly strict correlation always exists between a heterosexual male’s attitude to women and his attitude to gays (“the two others,” in Andrew Britton’s useful phrase), to the extent that the one can usually be deduced from the other. The repudiation of male as well as female homosexuality parallels the perception of women as, incorrigibly and unreachably, “other,” and underpins the impossibility of transsexual identification.

It is depressing to find, fifteen years later, precisely the same formation recurring in Sauve Qui Peut: after all, radical feminism and gay liberation had both vociferously intervened. Feminism has obviously left its mark on Godard, strongly affecting the surface of his films from Numéro Deux onwards; unfortunately, it seems to have left their basic assumptions about the unbridgeability of sexual difference untouched. In Sauve Qui Peut there is an obvious, agonized effort to adopt a female viewpoint: the greater part of the film’s running time is devoted to the parallel struggles for survival of Nathalie Baye and Isabelle Huppert (the inveterate sexism of our culture and its embedding in language are epitomized in the Anglo-American title, “Every Man for Himself”). The fleeting contact between them in a car, though brief and without sequel, is clearly the most positive moment in the film. Yet, for all the effort to the contrary, the true emotional center of the film remains the male protagonist, his death (though “accidental,” as in Masculin, Féminin) implicitly blamed on recalcitrant women—the wife and daughter who, like Jean Seberg at the end of Breathless, turn and walk away. The film’s interesting paradox is that this is the case despite the fact that, on the explicit level, the female protagonists are presented far more sympathetically than the man. His name happens to be Paul Godard. Godard has been eager to tell us in interviews that Paul was his father’s name (a fact of seemingly total irrelevance): one is surely at liberty to relate this Paul to the Paul of Masculin, Féminin and, through him, to the Paul of La Femme de Paul.

The unconscious formation seems confirmed, again, by the film’s repudiation of male homosexuality (here far more violent, obtrusive and unambiguous—the corollary, no doubt, of the film’s superficial commitment to feminism and the female viewpoint). In the first few minutes Godard introduces an adult bellboy who is determined to seduce “Paul Godard,” who is presented by Godard the filmmaker as a comic grotesque, and who is then vehemently rebuffed by Godard the character.

The above account is obviously very partial; it must not be understood as a dismissal of Godard, whose work remains among the most important produced during the past twenty-five years of cinema. What I have tried to fix here is the sense of a continuing block, for Godard apparently insurmountable, that has prevented his films from ever achieving the uncompromised progressiveness at which they clearly aim, and which can be argued to be responsible for the persistent sense of desperation and frustration that characterizes them. The obstinacy of that block in the work of a filmmaker who has consistently wished to be, and in many respects has been, in the forefront of cinematic and societal progress testifies to its formidable general presence in our culture, and to the sustained effort on the part of men and women alike that will be necessary to remove it. No unambiguously radical or progressive treatment of these issues within mainstream commercial cinema can be expected. The traces, however, remain worth investigating.

BUDDIES

Within their social context, the 70s “buddy” movies seem to me more interesting than is generally recognized. They have frequently been explained, or explained away, as a reaction to the women’s movement. This is doubtless an important factor in their constitution, but it is not the only one nor necessarily the prime determinant. Certainly the treatment of women in the films is extremely demeaning, both in their relegation to marginality and in the nature of the roles they are allocated. However, an interesting corollary accompanies this: if women can be dispensed with so easily, a great deal else goes with them, including the central supports of and justification for the dominant ideology: marriage, family, home.

It seems to me that the basic motivating premise of the 70s buddy movie is not the presence of the male relationship but the absence of home. The cycle (it has, of course, many precursors, going back to Huckleberry Finn and beyond) was effectively launched in 1969 by the appearance of three films that, between them, account for all the factors on whose permutations the subsequent films were built—Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Easy Rider, Midnight Cowboy. The later films, of which Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, Scarecrow, and California Split are the most distinguished and idiosyncratic, are all variations on the principles established in 1969:

1. The Journey Although the main body of Midnight Cowboy takes place in one city, the film opens with the male protagonist entering it and ends with him leaving it; similarly, the Las Vegas of California Split is a place the men come to and leave. In both cases the cities are stages in a journey. All the other films mentioned are structured upon journeys. The essential point is that either the journey has no goal or its ostensible goal proves illusory: “Florida” in Midnight Cowboy is obviously not intended to represent a possibility of resolution or fulfillment; Francis’ journey in Scarecrow is to an illusion he has constructed, to which the reality bears no resemblance.

2. The Marginalization of Women Of the six films, only Butch Cassidy has what appears to be a traditional female lead (Katherine Ross), and she is eliminated from the narrative some time before the film’s climax. Otherwise, women are merely present for casual encounters en route, “chicks” for the boys to pick up and put down. In Scarecrow, the pathetic, oppressed and vindictive woman Francis has abandoned (with child) years previously, and now intends to return to, confirms rather than contradicts the sudden unavailability of the woman-as-wife to provide a happy end.

3. The Absence of Home At the end of California Split George Segal (ditching his compulsive gambler buddy Elliott Gould) abruptly announces that he is going “home” but the film has made it clear that he no longer has any home to go to. In the films, home doesn’t exist, the journey is always to nowhere. “Home,” here, is of course to be understood not merely as a physical location but as both a state of mind and an ideological construct, above all as ideological security. Ultimately, home is America (“God bless America, my home, sweet home,” as the characters whose ethnic home America has effectively destroyed sing at the end of The Deer Hunter). The essential spirit of the buddy movie was marvelously epitomized in the advertising campaign for Easy Rider, which told us that the film was about two men who went searching for America and “couldn’t find it anywhere”: the films are the direct product of the crisis in ideological confidence generated by Vietnam and subsequently intensified by Watergate.

4. The Male Love Story For the moment, let us leave the word “love” in all its ambiguity (Howard Hawks, who resolutely denied the existence of any gay subtext in his films, described two of them as “a love story between two men”), and simply say that in all these films the emotional center, the emotional charge, is in the male/male relationship, which is patently what the films are about. Obvious, of course: yet the fact stands in direct opposition to the usual account of the Classical Hollywood text in terms of the happy ending in heterosexual union, promising the continuance of the nuclear family.

5. The Presence of an Explicitly Homosexual Character In the three 1969 movies, this occurs only in Midnight Cowboy (but there, twice). Yet it rapidly became a standard component of the cycle: the clownish gay of Mean Streets (a film in some respects central, in others peripheral), the transvestite of California Split, the brutal and frustrated prison inmate of Scarecrow. The overt homosexual (invariably either clown or villain) has the function of a disclaimer—our boys are not like that. The presence of women in the films seems often to have the same function: they merely guarantee the heroes’ heterosexuality.

6. Death In Butch Cassidy and Easy Rider both men die; in Midnight Cowboy one does. The pattern remains fairly consistent throughout the cycle, with variations: in Scarecrow, Francis becomes catatonic and may never recover; in California Split, Elliott Gould is trapped in the world of casinos, from which his partner can extricate himself. The male relationship must never be consummated (indeed, must not be able to be consummated), and death is the most effective impediment.

If the films are to be regarded as surreptitious gay texts, then the strongest support for this comes, not from anything shown to be happening between the men, but, paradoxically, from the insistence of the disclaimers: by finding it necessary to deny the homosexual nature of the central relationship so strenuously, the films actually succeed in drawing attention to its possibility. Read like this, the films are guilty of the duplicitous teasing of which they have often been accused, continually suggesting a homosexual relationship while emphatically disowning it. But this leaves many questions unanswered: Why did so many films of this kind get made in the 70s? Why did so many filmmakers apparently want to make them? If the answer to that is “because they made money,” then why were they so commercially successful? And why, in the 80s, have they virtually disappeared?

The formulation “surreptitious gay texts” is in fact too simple: it carries the suggestion that the central characters in the films are really homosexual, but the film can’t admit this. Such a suggestion, in its turn, rests on that strict division of heterosexual and homosexual which is one of the regulations on which patriarchy depends: if it is forced to admit that there are recalcitrant people who don’t or won’t conform to its norms, and if it recognizes that (perhaps) it should extend to them the magnanimity of toleration, then at least it can continue to set them aside, to separate them out.

I have suggested that what is fundamental to these films, as to so much of 70s Hollywood cinema, is the disintegration of the concept of home. That concept could also be named (one thinks here of course of the horror film) “normality”: the heterosexual romance, monogamy, the family, the perpetuation of the status quo, the Law of the Father. In discussing the horror film, I outlined the Freudian and post-Freudian account of the construction of that normality, its terrible cost, and its dependence upon the repression of an innate, free sexuality. What happens, then, when that normality collapses? What happens, specifically, within a cinema made by men and primarily for men? It produces male protagonists, identification figures for the male audience, the efficient socialization of whose sexuality can no longer be a given. The characters themselves are, of course, without exception social outcasts, voluntary dropouts; frequently criminals, they have placed themselves outside the pressures of patriarchy, which are all that stand in the way of the recognition and acceptance of constitutional bisexuality. They are also the protagonists of films made within an overwhelmingly patriarchal industry: hence they must finally be definitively separated, preferably by death. The films belong not only to social history but to social progress. Their popularity testifies, no doubt, to the contemporary “heterosexual” male audience’s need to denigrate and marginalize women, but also, positively, to its unconscious but immensely powerful need to validate love relationships between men. However one may regret the strategies of disownment, the films would admittedly be unthinkable without them: the heterosexual male spectator’s satisfaction would quickly be replaced by panic, and the films’ commercial viability would instantly disintegrate.

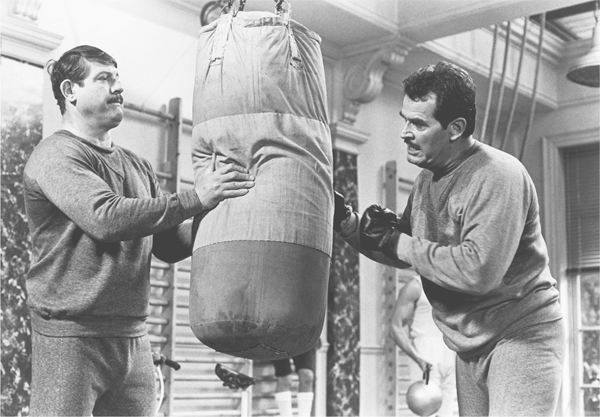

If I focus now on Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,1 it is not merely because it was directed by Michael Cimino: indeed, the link with his subsequent work is somewhat tenuous, and one could certainly not deduce from it the ambitions and audacity that were to produce The Deer Hunter and Heaven’s Gate. Of all the films in the cycle it comes closest to explicitness about the sexual nature of the male relationship (while still, of course, coding this rather than directly dramatizing it); it also, especially through its generic connotations, connects the male love story very directly with other aspects of the 70s action movie that reflect the collapse of confidence in home/America.

The film begins in a church and ends (almost) in a one-room schoolhouse: its action is framed between two of the major historical institutions for socialization, for the construction of normality, both marked by the presence of the American flag. Both, however, are presented explicitly as obsolete, empty shells rather than repositories of value. The church is the setting for a sermon by a phony clergyman, bank robber/con man, interrupted by a gunman’s attempt to assassinate him. The schoolhouse has been removed from its original location and fossilized as historical monument; its value within the narrative resides in its use as a hiding place for the loot—behind the blackboard, a secret ironic lesson in American capitalism. Thunderbolt/Clint Eastwood, contemplating the schoolhouse near the end of the film, respectfully murmurs ‘History!’: the admittedly peripheral concern with the image and reality of America, with American past and American present, links the film both to the western and to Cimino’s subsequent work. Church and schoolhouse (together with the middle-aged heterosexual bourgeois couples, both caricatured, associated with each) represent all that is left in the film of the concept of home. As for actual homes, none of the characters has one, or appears to regret its absence: Lightfoot, asked if he has “people,” remarks ‘I don’t even know any more, that’s weird.’

Despite its central relationship, the film from which Thunderbolt and Lightfoot derives most directly is none of the three source movies listed above, but Bonnie and Clyde. The basic narrative pattern is very close: the starting point of both films is the fortuitous encounter of two characters who, immediately attracted to each other, swiftly become a team; later, they are joined by a second, somewhat older couple with whom one of the initial couple has past links. The four become a gang, and plan and execute robberies. Ultimately, everything falls apart, and there is catastrophe and death. There are many incidental differences, but the major one is that both the heterosexual couples of Penn’s film become male couples in Cimino’s, where women play no part whatever in the central action, and from which the nostalgia for a lost home that haunts Bonnie and Clyde is conspicuously absent.

While women have no significant role in Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, the film’s treatment of them is not totally ignominious or without interest. One charming little scene (perhaps unique in the 70s buddy movie, where, typically, the women appear grateful for any crumb of attention the heroes may throw their way) actually foregrounds the feminist revolt against objectification: Lightfoot/Jeff Bridges, driving his truck, attempts to pick up a woman motorcyclist who responds by smashing at the truck with a hammer. The film is quite clear that the joke is on Lightfoot, not the woman. Totally irrelevant to the narrative, the moment, with its active and sympathetically presented woman engaged in a masculine pursuit and responding with aggressive behavior, is not irrelevant to the film’s pervasive if incoherent and unformulated sense of changing gender roles.

The relationship between Thunderbolt and Lightfoot is built throughout on ambiguities of sexuality and gender role. Their names carry obvious connotations of masculine and feminine, strength and grace, respectively, and these are systematically developed as the film proceeds. At times, the overt sexuality that is inevitably repressed in the mise-en-scène returns in the implications of the editing. The opening of the film crosscuts (before the two men have met) between Thunderbolt’s sermon and Lightfoot’s theft of a car from a second-hand dealer’s lot. From Thunderbolt’s text, “ … and the leopard shall lie down with the kid,” we cut immediately to the first shot of Lightfoot, whom Thunderbolt will refer to as “kid” throughout the movie; the text is repeated, without obvious narrative motivation, later in the film, as if to underline its implications.

Two other components of the structure of character relationships serve in different ways to validate the Thunderbolt-Lightfoot relationship as the film’s emotional center. The obligatory sex scene involving women, whose usual function, as already noted, is merely to guarantee the men’s heterosexuality, is used here to suggest Thunderbolt’s lack of sexual interest in women and Lightfoot’s casual attitude to them. (It is interesting that, if one reads the central relationship as basically sexual, it is Lightfoot, at once the more feminine and the more childlike of the two men, who is the more clearly presented as bisexual, or whose sexuality might be regarded as undefined and open; in this respect he can be considered a forerunner of the Christopher Walken character in The Deer Hunter.) The second male relationship, Red and Goody (George Kennedy, Geoffrey Lewis), is used throughout as a foil to the growing commitment of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. The two couples, in fact, aside from being male, correspond closely to the good couple/bad couple opposition so common in Classical Hollywood cinema, where the narrative moves toward the elimination of the bad couple in order to construct the good. Here, the Red-Goody relationship is characterized by disorder, tension and contempt (culminating in Red’s brutal dumping from a car of the wounded Goody—“You’re gonna be dead soon anyway”), in contrast to the increasing mutual trust and dependence of Thunderbolt and Lightfoot. It is appropriate, then, that Kennedy’s brutal masculinity should be used in one scene to highlight, favorably, Lightfoot’s sexual ambiguity: Lightfoot, responding to the older man’s question as to what he did with a naked woman, enrages him by kissing him on the mouth (though placing his own hand in between). Red’s outrage expresses itself in an indignant “You kids don’t believe in anything anymore,” to which Lightfoot responds by blowing kisses at him.

The film moves toward the climactic robbery sequence throughout which Lightfoot is disguised as a woman. The narrative pretext for this is fairly flimsy, its logical necessity seeming to lie rather in the development of the relationship. Lightfoot’s masquerade interestingly avoids the obvious twin temptations of female impersonation in the Hollywood cinema—on the one hand, the caricature of femininity, on the other, the playing up of masculine clumsiness and awkwardness in the interests of comedy: without being particularly graceful or ungainly, he makes an attractive and appealing young woman. Significantly, from the point where the disguise is adopted, the film keeps the two men apart for as long as possible, and the sexual overtones are restricted again to the implications of the editing. Light-foot walking the street in drag is intercut with Thunderbolt removing his clothes in preparation for the robbery; Lightfoot’s masquerade is then juxtaposed with the “erection” of Thunderbolt’s enormous cannon. This culminates in the film’s most outrageous moment: in a washroom Lightfoot, back to camera, bends over the watchman he has knocked out, his skirt raised to expose his ass clad only in the briefest of briefs, from which he extracts a revolver; the film immediately cuts to Thunderbolt, fixing his cannon in its fully erect position. In its recent overt treatments of male homosexuality, the Hollywood cinema has never dared give us anything comparable to that.

The ending, with the bad couple destroyed, initially celebrates the union of the heroes with the abrupt discovery of the relocated schoolhouse and the recovery of the hidden money, a celebration clinched by Thunderbolt’s gift to his buddy of the possession he has always coveted, a white Cadillac. Lightfoot’s declaration that they are “heroes” crystallizes much of the spirit of the 70s interlocking road-movie, buddy-movie, gangster-movie cycles: the heroes of American culture can now exist and operate only outside the confines and norms of the American establishment, the schoolhouse a historical relic of an obsolete socialization. The definition of the heroism is not merely in terms of criminality, but in terms of escaping the constraints of normality. The two men drive off together, not to but away from home: there is no sense of a specific destination, rather of an extended honeymoon after what amounts to a wedding celebration complete with extravagant gift. Of course, Lightfoot is already dying (a delayed reaction to his brutal beating by Red): given the cultural constraints, it is one of the most necessary deaths in the Hollywood cinema. It is important that he be the one to die, rather than the stoical, resolutely and unambiguously masculine Thunderbolt, whose sexuality is, on the level of overt signification, of gender stereotyping, never in question (after all, he is played by Clint Eastwood). It is the essentially gentle Lightfoot, with his indeterminate sexuality, his freedom from the constraints of normality’s gender roles, and his air of presocialized child, who constitutes the real threat to the culture.

Dog Day Afternoon provides the ideal transition from Thunderbolt and Lightfoot to the gay-themed movies of the 80s, combining as it does dropout bank robbers with explicitly gay characters. The film’s movement is central to the American cinema since The Chase: a rapidly escalating progress from a precarious, already troubled order into breakdown and chaos—a progress expressed through the shift of tone from comedy to desperation and underlined by the movement from light to darkness in the film’s strict time scheme. The shift is centered on the feature that gives Dog Day Afternoon its particularity, the protagonist’s gayness: from the moment of the revelation that his second “wife” (the one he is most eager to contact and the raison d’être of the robbery) is male, the presentation changes. This is most obviously signaled through the changed attitude of the audience within the film, the crowd that collects to watch: having adopted Pacino as a sort of anti-authoritarian folk hero and identification figure during the first part of the film (especially as a means of expressing resentment of the police), they detach themselves from him after the appearance of his lover Leon: an audience participation “happening” becomes a spectacle, almost the “freak show” Pacino denounces. For the cinema audience there is a parallel (but not identical, and much less extreme) modulation. At screenings I have attended, members of the audience have audibly taken time to adjust, but it is to the film’s credit that its gays never become a freak show for anyone outside it (the one ominous moment, Leon fainting in the arms of the police in apparent stereotypical effeminacy, is quickly explained: he has been brought straight from hospital). But it is from the time we know he is gay that we are also invited to see Sonny as neurotic (rather than just endearingly incompetent)—particularly through Leon’s account of the impossibility of life with him.

The treatment of gayness in Dog Day Afternoon defines very precisely the ideological limits within which the contemporary American cinema operates. It is, I believe, the first American commercial movie in which the star/identification figure turns out to be gay, a revelation cunningly withheld—in the terms in which the narrative is constructed, irrespective of factual foreknowledge—until the audience has been drawn into a qualified but sympathetic complicity with him. It is also (and I am grateful for this to Lumet, Pacino, and Chris Sarandon) one of the only films with gay characters that I can watch without anger—anger from which Fassbinder, for example, is not exempt. Fox, whatever its quasi-Marxist intentions, seems to go out of its way to reinforce stereotyped images of gay men (petty and malicious unless just stupid like the hero) and gay relationships (destructive and exploitative) for the bourgeois audience: see most of our “liberal” journalists’ enthusiastic reviews, celebrating the film’s truth and honesty about “the homosexual condition.”

Dog Day Afternoon reinforces the popular association of gayness with neuroticism and necessary unhappiness, but at least the film works against any assumptions in the audience of superiority or safe detachment. Indeed, one of the most interesting aspects of the film is its assimilation of gayness into the syndrome of existential uncertainty, breakdown-of-traditional-values, dissolution-of-borderlines, so central to the contemporary American cinema. Another is its curious inverse relation to the male duo/road subgenre: there, the male couple are together all the time, traveling freely across the continent in close comradeship, and the films are careful to signal their interest in women (albeit casual and, in most cases, degradingly “merely” sexual); in Dog Day Afternoon the couple are explicitly gay, their relationship is disastrous, each is trapped in a separate building, and they converse only by telephone. Keeping Sonny and Leon apart (like Thunderbolt and Lightfoot when the latter is in drag) spares the spectator the potential embarrassment of imagining anything they might do in bed together. It is also consistent with the film’s general desexualization of Sonny: his other wife is a comic grotesque, fat and hysterical, and although she is the mother of his two children we are never invited to imagine any sexual attraction between them.

If gay stereotyping is intelligently avoided in the performances of Pacino and Sarandon, it forces its way, significantly, back in at a later point: the lateral track along the line of gay militants reveals all the usual stock figures that represent the popular concept of the overt homosexual. Inherent in the gay liberation movement is a significance going far beyond the rights of homosexuals: it offers the most direct and practical challenge imaginable to the central, stubborn feature of the dominant ideology, the traditional concept of marriage and family. It cannot, therefore, within the popular commercial cinema, be treated seriously, at least in its militant and organized aspects. The effects of this in Dog Day Afternoon go far beyond the brief unfortunate moment of the militant gay demonstration; the particular nature of the hero is also determined by the same ideological constraints. Our sympathy for him is clearly meant to increase because the militants opportunistically try to use him for their cause: he is essentially the little guy, minding his own business (apart from robbing a bank), tossed about by rival factions, who just wants to be himself—a relatively safe liberal concept which the establishment has never had much difficulty in assimilating. Despite armed robbery, gayness, and an occasional spontaneous protest outburst, Sonny is not an ideologically dangerous character. The film makes him comically incompetent as a robber, carefully dissociates his gayness from any organized movement, and repeatedly stresses his political (or apolitical) confusion: he fought in Vietnam and isn’t ashamed of it, and he used to be a Goldwater supporter.

LOVERS

At first sight, the 80s movies on gay themes (of which I shall discuss Making Love and Victor, Victoria, the two that most interestingly raise the problems of treating the subject of male homosexuality positively in mainstream cinema) might appear an unambiguous advance on the 70s buddy movie: the sexuality is openly acknowledged, male couples are shown embracing and/or in bed together, women are no longer marginalized or reduced to mere alibis. Certainly there are positive things to be said, and I shall say these first; ultimately, however, the constraints within which the films operate seem more illuminating than the superficial advances in frankness and liberalism. Apparently representing the only progressive trend in 80s Hollywood cinema, the films in fact belong very much to their period, constitute no real anomaly, paradox or problem.

Insofar as such things can be calculated, one can deduce that the direct social effect of Making Love has probably been (within its somewhat limited commercial success, and in relation to the somewhat limited audiences at which it seems to have been aimed) very good. It seeks discreetly to acclimatize its audience to homosexual lovemaking, presenting it no differently from the ways in which a bourgeois cinema dedicated to “good taste” and the family audience has typically presented heterosexual embraces; it suggests (within careful ideological limits, to which I shall return) that it is legitimate to choose to live as gay, with a lover of the same sex; it offers two attractive, moderately popular young stars, potential identification figures, as homosexual lovers. Unlike, for example, Taxi zum Klo, it is the kind of film to which your average gay bourgeois male might profitably take his parents. Further, such a film might help a number of hitherto closeted gays to “come out”: its very existence as a popular entertainment, its very format of compressed soap opera, its public display for general audiences, all suggest the growing acceptance of gayness, its potential respectability. In addition, the screenwriter, Barry Sandler, himself felt able to come out during the making of the film: incredible as it seems, he appears to be still the only openly gay figure in the Hollywood industry (although George Cukor managed nobly to declare himself before he died). His screenplay, cunningly contrived in relation to the engagement and leading on of middle America, with a number of extremely well-observed and well-written scenes, is clearly the film’s major strength, together with the performances of Michael Ontkean and Harry Hamlyn, which avoid all the obvious pitfalls of stereotyping and condescension. Conversely, the film’s most apparent limitation is blazoned in the opening credits: “An Arthur Hiller Film.” Like every other Arthur Hiller film its directorial ambitions nowhere transcend the constrictions of a professionally efficient made-for-TV movie, ensuring that any continuing interest it has will be purely sociological and historical.

The comic vitality of Victor, Victoria, on the other hand, should ensure it a life after its sociological and historical interest has lost its topicality. It is also, in many respects, a very pleasurable film for gay people to share with large general audiences. Having promised Julie Andrews and comedy in the opening credits, the film is confident enough to confront its audience with male homosexuality in its first shot: the camera moves back from a window overlooking a Paris street, moves left over a bedside table on which is a photograph of Marlene Dietrich (Sternberg period) in male clothes, to show Toddy (Robert Preston) asleep in bed, then continues its progress to reveal that his bed companion is another man. It is important that it is set, as the first view of the stylized street set establishes, in an artificial never-never land: Paris and the 30s, but not a real place or a real time. Its play with artifice is suggested by giving its leading French character (Toddy) an American name and its leading American character (James Garner) a French one (Marchand), and by its refusal to make language and accent problematical, giving French accents only to peripheral comic characters, such as Graham Stark’s skeptical waiter. We are led at once into a world whose relation to our own is far more ambiguous and fanciful than that offered by the simple contemporary representationalism of Making Love. From there, the film quickly gains the complicity of its audience with the introduction of Andrews and a series of brilliantly executed comic scenes built upon our identification with her and her predicament (impoverished singer in a foreign city) and culminating in the establishment of her friendship with Toddy.

The complicity is strong enough to take in its stride some directly (and, for Hollywood, outspokenly) didactic moments such as Andrews’ assertion to Garner that the only people who consider homosexuality sinful are “respectable clergymen and terrified heterosexuals,” and some magnificent moments of gay-positive comedy. Gay people are accustomed to experiences of discomfort in the cinema: all those moments when a grotesque or monstrous stereotypical gay character appears and certain—shall we say?—more uninhibited members of the audience shout out “Faggot!” at the screen (personal memories of this include Siegel’s Escape from Alcatraz and Wiederhorn’s Meatballs II). The experience is not unlike what Jewish people might have felt had they wandered inadvertently into screenings of the anti-Semitic films made in Germany under the Nazi regime. It is to the credit of films like Making Love and Victor, Victoria that they have made it—temporarily at least—less easy for Hollywood filmmakers to capitalize on such prejudice except on the lowest levels of mindless exploitation. Consider, as an example of the successful reconditioning of the mainstream audience, the following moment from Victor, Victoria (greeted, on both occasions on which I saw the film in a full house, by spontaneous applause). Victoria (Andrews), her clothes shrunk by rain, dresses in a suit left behind by Toddy’s obnoxious and venal lover. The lover returns unexpectedly, and Victoria hides in the closet. As he opens the closet to retrieve his clothes, the lover contemptuously addresses Toddy as “You pathetic old queer.” In immediate response, Victoria bursts from the closet, punches him in the nose, and subsequently boots him out of the apartment. Previous movies would have got their laugh, and their applause, on the lover’s remark; this film gets it on Victoria’s reaction. There is also the later moment, also commonly applauded, when Toddy, informed by Norma (Lesley Ann Warren) that she thinks a good woman could reform him, responds that he thinks a good woman could reform her. From that, it is but a step (though still an audacious one) to the moment where King Marchand’s hefty bodyguard Mr. Bernstein (Alex Karras) comes out, kissing his boss on the cheek. At its best, Victor, Victoria is a salutarily educational movie, undermining and transforming its audience’s entrenched and continually reinforced attitudes through sympathy and laughter.

I do not wish to be ungenerous to these movies (some will say that I have already conceded too much, but I think their positive aspects have been consistently underrated in the gay and radical press). It has become increasingly clear, however, since their release, that they are oppositional films only on the most superficial levels. On deeper levels, they retain their niche within the dominant ideology of 80s America. That familiar monster “the dominant ideology” is—even in an overwhelmingly reactionary period like our own—neither monolithic nor static. It might be likened to a protean octopus: like Proteus, it can perpetually transform its appearance while remaining the same underneath; like an octopus, it can reach out in all directions and engorge whatever it thinks it can digest (also like an octopus, it sometimes makes mistakes). Films like Making Love and Victor, Victoria testify to the continuance of the tradition of American liberalism; they also testify to its frailty and to its vulnerability to the pressures of compromise. Liberalism has always been a phenomenon the octopus digests quite easily.

The background to the 70s buddy movies was, we have seen, the collapse of the concept of home, with all its complex associations; the background to the 80s gay movies is, precisely, its restoration and reaffirmation, an operation that makes clear the extent to which the restoration of home is synonymous with the restoration of the symbolic Father. (The Father may either forbid or permit; the permitting is just as authoritarian as the forbidding.) In fact, two ideological strategies, closely interconnected, operate within the films:

1. Separation I argued that the ambiguity or evasiveness of the buddy movies can be read positively in the context of the collapse of confidence in normality and in relation to Freudian theories of constitutional bisexuality: the men are explicitly defined as heterosexual yet involved in what can only be called a “male love story.” It is striking that, just before the sudden outcrop of explicitly gay movies, the buddy cycle virtually ends. My Bodyguard, with its extraordinary motorbike-riding montage sequence in which the two male teenagers are seen trying out all available positions, is perhaps its last fling; An American Werewolf in London might be seen as a corrupt mutant form, the male relationship made repulsive and impossible by the fact that one of the partners is progressively decomposing throughout the film. It is precisely sexual ambiguity that Making Love and Victor, Victoria avoid: sexual orientation is separated out; there are heterosexuals and homosexuals, but they are two distinct species.

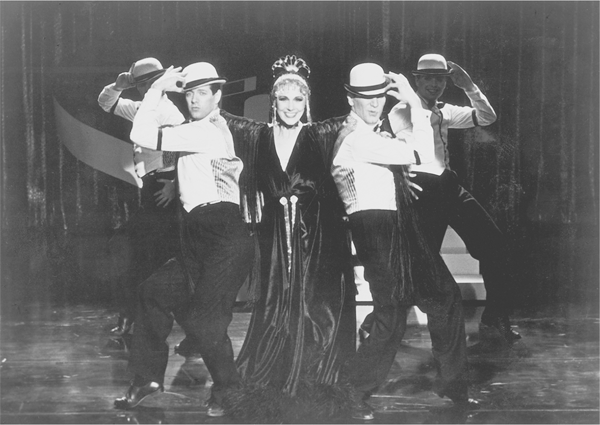

Victor Victoria

Julie Andrews as a woman impersonating a man impersonating a woman

Images of masculinity: Alex Karras and James Garner

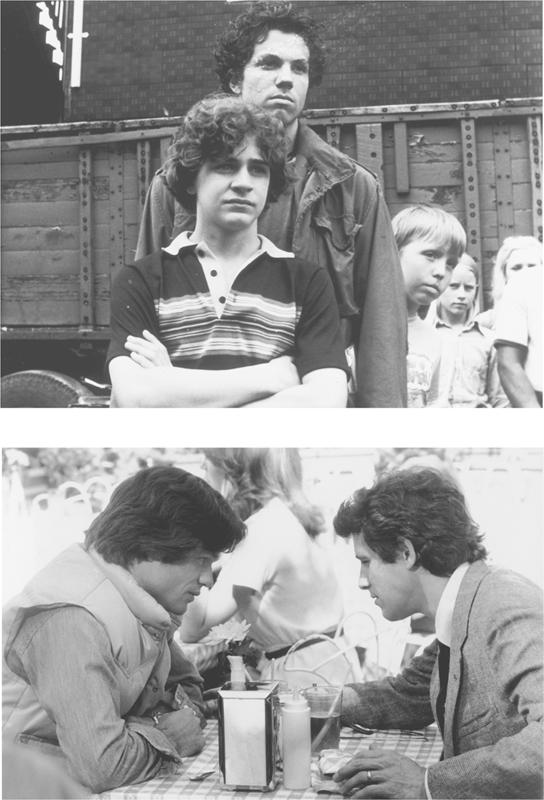

From Buddies… (Chris Makepeace and Adam Baldwin in My Bodyguard) … to Lovers (Harry Hamlin and Michael Ontkean in Making Love)

Certain explicit aspects of the two films appear to counter this assertion. Zack (Michael Ontkean) is, after all, apparently happily married until he “discovers” he is gay; Victoria (as Victor) challenges Marchand as to whether he’s never had any doubts about his sexuality. But such moments are negated by the overall movement of the films. From the time when Zack defines himself as gay there is never the slightest indication that he might relate sexually to women as well as men; the implication (strengthened by a few more or less subtle hints) is that his relationship with his wife was based on friendship and mutual respect, and that, although he was able to function sexually with her, that side of the marriage was always a bit of a strain. The problem here is, of course, that this depiction is not only plausible but probable: our culture is committed to separating out, true bisexuality seemingly being very rare: the infant is “ideally” constructed as exclusively heterosexual and becomes exclusively homosexual if the programming somehow “goes wrong.” The film can plead the usual alibi of realism. Yet nothing in its generally glib and superficial analysis raises the essential questions. By merely reproducing the notion that everyone is, in some inexplicable way, either exclusively one thing or the other, it reinforces and perpetuates it.

Victor, Victoria is somewhat more complex: it does contain one scene that raises the issue of innate bisexuality—significantly, a scene many have found redundant, unnecessary, or obscure. Marchand and Victoria (disguised as a man but known by Marchand to be a woman) go dancing in a gay male club. After a while, Marchand becomes so disturbed by the presence of the male couples dancing in close proximity to him that he feels compelled to leave. Instead of going back to the hotel with Victoria, however, he goes alone to a laborers’ bar, where he deliberately provokes the clientele into a brawl; after violently punching each other, the men end up (as buddies) singing in each other’s arms. One must, I think, read the scene as follows: Marchand’s disturbance at the gay couples is more than mere homophobia; he feels his own manhood threatened, and goes off ostensibly to reaffirm it; however, what he really wants is the close physical companionship of other males, though, because of his inhibitions, he can permit himself this only under cover of an overt display of masculinity (violence, aggression).

That scene apart, however (and in its inexplicitness it scarcely goes further than the buddy movies or, for that matter, Hawks’ A Girl in Every Port), the film is every bit as systematic as Making Love in sorting out its gays from its straights. What should have been its most audacious moment—Marchand telling Victor/Victoria that he wants to kiss her even if she is a man—is in effect its most pusillanimous: we know that he knows that she isn’t. And Victoria’s own heterosexuality, despite her own didactic utterances, is never called into question.

2. The Restoration of the Father This sorting out serves, in fact, a further purpose: the consigning of gays to their place within a liberal hierarchy in which the symbolic Father (the heterosexual male) remains the dominant figure. What happens in both films is in effect—an effect quite contrary to the filmmakers’ very evident good intentions—the putting down of gayness. As Richard Dyer has pointed out in conversation, the implication of the ending of Making Love (it derives, significantly, from Les Parapluies de Cherbourg) is that, for all their protestations to the contrary, the two leading characters are both unhappy: if only Zack had not been gay, everything would have been perfect. The film does nothing very effective to counter this: Zack’s permanent gay relationship is presented in the most perfunctory manner possible, the little we see of it suggesting that it is an imitation of heterosexual marriage, only lacking the child (significantly, a son) Zack always wanted and that his ex-wife now has with her new husband. As for Bart (Harry Hamlyn), although the opening of the film very emphatically accords him equal prominence with Claire (Kate Jackson), from the point where he rejects the possibility of a monogamous union with Zack the narrative can no longer encompass him: he disappears into a film noir-ish blur of sidewalks and neon lights. Earlier, the film tries very earnestly to permit him a voice—to permit, that is, a defense of independence and promiscuity; the attempt signally fails, leaving us with the heterosexual couple or its gay imitation as the only valid life-style. This reading is thoroughly confirmed by the presentation of the other promiscuous gay man Claire visits in her search for Zack: he reveals himself as insensitive, materialistic, devoid of aspirations beyond an endless procession of “tricks.” The restoration of normality, the elimination from the narrative of any ideological threat to it, is underlined by the way in which both Zack and Claire are shown to have teamed up with father figures. Predictably, the film’s putting in place of gay liberation is accompanied by a parallel operation in relation to feminism: Claire, who was earlier allowed to assert that she thought she could be independent, ends up apparently content with her role as wife and mother, with no further mention made of her work.

The same parallel operations are performed in Victor, Victoria: its last scene simultaneously confirms the position of gays as comic and the position of women as inevitably subordinate. Throughout the film, Victoria’s essentially compliant female sexuality (for all her masquerade) has been contrasted favorably with the aggressive female sexuality of Norma, presented as grotesque and castrating. In the final scene, in direct contradiction to her earlier assertions, Victoria abandons the freedom of her male disguise in favor of her relationship with Marchand, while Toddy performs in her place in drag. The film utilizes a so-called time-honored tradition going back through Mozart and Shakespeare, but which was never free of class connotations: the comic couple used as a foil to the serious couple. Typically, in the past, the serious couple was aristocratic, the comic couple servants or commoners; now, the serious couple is straight, the comic gay. The Victoria/Marchand relationship is presented in terms of a commitment deserving sacrifices; the Toddy/Bernstein relationship is allowed no real importance whatever, and is further undermined by Toddy’s casual and brutal reference to Bernstein’s “making a permanent dent in the bed.” (Silkwood performs a precisely analogous serious couple/comic couple strategy for dealing with lesbians.)

One is forced finally to reflect that, while they dramatize and promote certain liberal attitudes toward homosexuality that are without precedent in the Hollywood cinema, the ultimate and insidious ideological function of these films is to close off the implications of a threatening, antipatriarchal bisexuality that were opened surreptitiously in the 70s. Then, of course, one or both of the male protagonists had to die: patriarchy could not safely contain their relationship. Today, the explicitly gay couple can be permitted to survive and even be designated happy (though the happiness is never dramatized)—provided they accept their place.

1. Since I completed this essay, a friend has directed my attention to an article on the film in Jump Cut, November/December 1974, by Peter Biskind (“Tightass and Cocksucker: Sexual Politics in Thunderbolt and Lightfoot”). Biskind’s account of the film is far more hostile than my own: he seems unduly disturbed by what he sees as “its frank and undisguised contempt for heterosexuality,” without at any point acknowledging the “frank and undisguised” contempt for homosexuality that pervades our entire culture. Nevertheless, there are considerable areas of overlap in our interpretations.