THE HOMOSEXUAL SUBTEXT: Raging Bull

Without taking bisexuality into account, I think it would be scarcely possible to arrive at an understanding of the sexual manifestations that are actually to be observed in men and women. —Freud, Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality

Although this discussion will eventually center upon Scorsese’s Raging Bull, its concerns are far wider than a reading of a single film. I want to develop certain ideas or trains of thought, which remain as yet somewhat tentative and fragmentary, arising out of recent critical explorations into the operations of classical narrative. I will focus especially on the notion that classical narrative is centrally concerned with the organization of sexual difference within the patriarchal order, a project whose ultimate objective must be the subordination of female desire to male desire and the construction/reinforcement of a patriarchally determined normality embodied by the heterosexual couple. Clearly, Raging Bull should strictly be described as postclassical, but there is obviously no clean break, and I shall be as concerned to establish continuity as divergence. Scorsese’s film—which I see as possessing both the distinction and the representativeness whose fusion has always been a necessary, defining characteristic of great art—relates to classical Hollywood narrative very interestingly and continues to reveal many of its structural operations: those principles of symmetry, repetition, variation, and closure (“the end answers the beginning”) that, especially, Raymond Bellour has investigated systematically. One of my aims is to rescue both classical and postclassical narrative from that school of criticism (in relation to which I find Bellour’s position curiously ambiguous and undefined) that would jettison it altogether in favor of avant-garde experimentation, on the grounds that narrative can only lead to the reconstitution of the patriarchal order, the reinforcement of patriarchal ideology.

Using Hitchcock as a reference point, but also pointing beyond him to the work of post-classical filmmakers like Scorsese, I want to start by raising three questions (or question clusters) about classical narrative and the restoration of order that I don’t think have yet been definitively answered or closed off.

1. Order If classical narrative moves toward the restoration of an order, must this be the patriarchal status quo? Is this tendency not due to constraints imposed by our culture rather than to constraints inherent within narrative itself? Does the possibility not exist of narrative moving toward the establishment of a different order, or, quite simply, toward irreparable and irreversible breakdown (which would leave the reader/viewer the options of despair or the task of imagining alternatives)?

2. Tone If a given narrative does move toward the restoration of the patriarchal order, what is the work’s attitude to that restoration? The order itself may, after all, have been called into question and undermined, its monstrous oppressiveness exposed. The attitude to its restoration, then, need by no means be one of simple optimism or endorsement: it could be tragic or ironic. Tone is a phenomenon with which semioticians appear to have great, if unacknowledged, problems, which they ignore rather than resolve: hence Bellour can pursue at length the “Oedipal trajectory” of North by Northwest without ever considering that its major father figure, the Professor (Leo G. Carroll), is presented consistently as a cynical opportunist. Hitchcock’s resolutions, in fact, are frequently characterized by an idiosyncratic fusion of the ironic and the tragic. The narratives of Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, and Strangers on a Train all move toward the construction of the heterosexual couple and the restoration of patriarchal normality, but the audience is left with a feeling of tension, frustration and emptiness rather than satisfaction (let alone plenitude): the films have systematically dismantled the order that is perfunctorily (some might say cynically) restored.

3. Identification I remain dissatisfied with the current theoretical accounts of the construction of the viewer’s position by classical cinema, especially with regard to the dichotomy of male/female spectatorship. More work needs to be done on the phenomenon of transsexual identification and the complex implications of this. I don’t believe that Hitchcock’s films (which frequently encourage identification with the female position for viewers of either sex) construct a position for women that merely teaches them to acquiesce in punishment for transgression and to submit to the male order; nor do they construct the complementary position for men. Take, as the extreme case, Vertigo: from the moment when Hitchcock allows us access to the consciousness of Judy/Kim Novak, the male identification position is undermined beyond all possibility of recuperation; no spectator of either sex, surely, acquiesces in Judy’s death or perceives the male protagonist’s treatment of her as other than monstrous and pathological. Hitchcock’s narratives (if one reduces the term to story line) may move toward the restoration of the patriarchal order; their thematic might be defined as the appalling cost, for men and women alike, of that restoration, and the exposure of heterosexual male anxieties.

This begins, I hope, to suggest ways in which the current impasse in criticism of classical narrative—the jaded sense that all narratives are really the same and that the critic’s task is to demonstrate this over and over again—might be broken. I want now, however, to take a giant step further, with the help of Freud, in an attempt to open up new paths of exploration. I take as a starting point what may yet prove to be the most important of all Freud’s discoveries (though it wasn’t only his), the implications of which he himself was obviously reluctant to pursue—a reluctance that our culture has in general continued to share: the discovery of constitutional bisexuality. Freud found, to his own evident surprise and discomfiture, that in every case he analyzed, without exception, the analysis revealed at some level the traces of repressed homosexuality; this revelation accorded with his investigations into the sexuality of children, the theory of the infant’s “polymorphous perversity,” and the existence in children of all those erotic impulses that our adult world of patriarchal normality labels “perversions.” It need not surprise us that Freud, himself an eminent turn-of-the-century Viennese patriarch with his own stake in that normality, was quite incapable of following through on the revolutionary implications of this discovery: he could only fall back lamely on the ideological assumption, never questioned or subjected to scrutiny, that the process of repression, the progress toward and into normality, was both desirable and inevitable, despite his very clear awareness that that very normality was characterized by misery, frustration and neurosis. For it is upon the repression of bisexuality that the organization of sexual difference, as enacted within our culture and as represented upon our cinema screens, is constructed. There is no reason to assume, as Freud appears to have assumed, that repression is somehow necessary for the development and continuance of human civilization in any form; it is necessary only for the continuance of patriarchal civilization, with its dependence upon a specific, rigid and repressive organization of gender roles and sexual orientation. It seems probable that the contemporary crisis in heterosexual relations can be satisfactorily resolved only by reversing the process of repression, liberating what is repressed, and restoring to humanity that portion of its rightful legacy that our culture has consistently denied it. This gives a new definition to the project known as gay liberation, which has generally been taken to mean something like “society should tolerate homosexuals.” This in itself constitutes an interesting ideological strategy, redolent of the nervous compromises of liberalism: homosexuals are identified as a separate, fundamentally different group; thus homosexuality is simultaneously tolerated and disowned by being defined as “other.” The gay liberation that I have in mind involves, obviously, the liberation of heterosexuals; Raging Bull—to leap ahead for a moment—can be read as an eloquent sermon on the urgency of such a project.

What is repressed is never, of course, annihilated: it will always strive to return, in disguised forms, in dreams, or as neurotic symptoms. If Freud was correct—and I see no reason to suppose otherwise—we should expect to find the traces of repressed homosexuality in every film, just as we should expect to find them in every person, usually lurking beneath the surface, occasionally rupturing it, informing in various ways the human relationships depicted. It is my purpose to examine the manifestations of those traces in Raging Bull, a film in which they exist threateningly close to the surface, to the film’s conscious level of articulation, accounting for its relentless and near-hysterical intensity. The title of my chapter comes from Martin Scorsese himself: he told me in a conversation that, though he was not aware of it while making the film, he now saw that Raging Bull has a “homosexual subtext.” However, my title refers, at least by implication, far beyond the homosexual subtext of one film to the homosexual subtext of our culture.

Before I turn to Scorsese’s film, however, let me throw in one last aside on Hitchcock to complement, in the light of Freud, what I have said above. Everyone should be aware of the pronounced strain of homophobia that runs through Hitchcock’s work, although it is homophobia of a very peculiar kind, as much fascination as repulsion. A significant number of his villains are coded, more or less explicitly, as homosexual (together, curiously, with one of his most morally admirable characters, Louis Jourdan in The Paradine Case): the transvestite killer in Murder, Judith Anderson in Rebecca, John Dall in Rope, Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train. Further, these figures relate closely to others whose homosexual connotations (if they exist) are unclear but who are all associated with perverse sexuality: Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt, Anthony Perkins in Psycho, Barry Foster in Frenzy. The attitude to these characters is always ambivalent: if evil—all are murderous, and all but one are actual killers—they are also arguably the most attractive, certainly the most fascinating figures in their respective films, and the films’ true sources of energy. No one, to my knowledge, appears to have connected this striking phenomenon with Hitchcock’s treatment of heterosexual relations. Homophobia is, in fact, a very interesting illness. It is characterized by the sense that it doesn’t need an explanation, that it is somehow natural to hate homosexuals, and by its total irrationality, the fact that no possible explanation for it exists outside the psychoanalytical one. It is clearly enough a particular form of heterosexual anxiety: the homophobe hates the precariously repressed homosexual side of himself. Future work on Hitchcock might profitably pursue the connection between the sexual anxiety expressed in the homophobia and the sexual anxiety expressed in the treatment of heterosexual relations—the absence, in Hitchcock’s films, of any presentation of a mutually fulfilling sexual relationship, the emphasis throughout his work being on the obsession with domination and power. One can certainly see the films (and herein lies their potential for revolutionary use) as foregrounding and exposing the mechanics of the heterosexual male power drive, the obsession with controlling, containing, defining or punishing female sexuality.

At first sight, Raging Bull seems a particularly difficult kind of film to which to gain critical access. The performance style favored by Scorsese and De Niro—derived from the Actors’ Studio and the Method school, with its emphasis on spontaneity, improvisation and behaviorism—tends to deflect attention from structure and the kinds of meaning generated by structural interaction and instead to focus it upon acting and character study. Thus one of the common misconceptions of New York, New York is that it is “simply” about two individuals; and Andrew Sarris can complain of Scorsese’s lack of a sense of structure (meaning, presumably, that the films do not correspond to the well-made scenario of classical Hollywood) and see Raging Bull as the stringing together of a number of extraordinary moments. The question has also been raised as to why Scorsese wanted to make a film about so unattractive, unpleasant and limited a character as the Jake La Motta created by himself and De Niro. The meaning the film finally seems to offer its audience—La Motta’s progress toward partial understanding, acceptance or “grace”—must strike one as quite inadequate to validate the project, and actually misleading: the film remains extremely vague about the nature of the grace or how it has been achieved. Any suggestion of that kind is in fact thoroughly outweighed by the sense the film conveys of pointless and unredeemed pain, both the pain La Motta experiences and the pain he inflicts. But, if one rejects the film’s invitation (at best half-hearted, and deriving, one may assume, more from Schrader than Scorsese) to read it in terms of a movement toward salvation, one must accept the invitation to read it centrally as a character study (though “case history” might be the more felicitous term). The film’s fragmented structure can be read as determined by La Motta’s own incoherence, by Scorsese’s fascination with that incoherence and with the violence that is its product. That audiences are also fascinated, not merely appalled, by La Motta, testifies to the representative quality that the film’s apparent concentration on a singular individual seems to deny. If we can make sense of La Motta we shall make sense of the film’s structure and, simultaneously, be in a position to explain the fascination that La Motta and the film hold for our culture at its present stage of evolution.

Seeking a way into the film, we may begin with the montage sequence that intercuts La Motta’s home movies with a series of his fights. The sequence is privileged in two ways: first, it is a very unusual kind of sequence, virtually unclassifiable within the categories of Metz’s “Grande Syntagmatique” (it combines certain defining characteristics of the bracket syntagma, the alternating syntagma and the episodic sequence); second, it is marked by the only intrusion into the film (opening credits apart) of color. The intercutting suggests an intimate relationship between two seemingly disparate aspects of La Motta’s life—that the fights are somehow necessary to the construction of “domestic happiness” that is the home movies’ raison d’etre. By this point (about a third of the way through) the film has definitively established black and white as its reality; conversely, then, color signifies illusion. This illusion of domestic happiness is presented clearly as Jake’s construction: he “directs” the movies, he brings Vickie gifts, he drops her in the swimming pool, etc. At the same time, the fights are given an illusory quality of another order through the use of technical devices such as stills and slow motion: reality as dream.

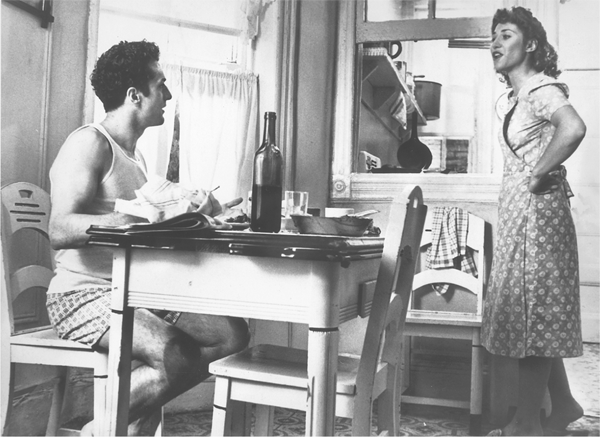

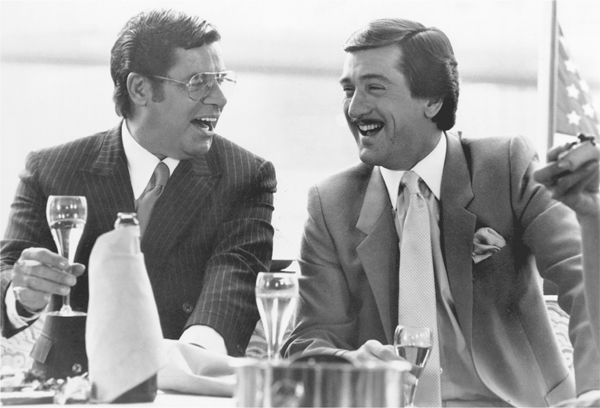

Raging Bull: Jake’s Marriages

Jake La Motta (Robert De Niro) above with his first wife (Lori Anne Flax) …

… and his second wife (Cathy Moriarty).

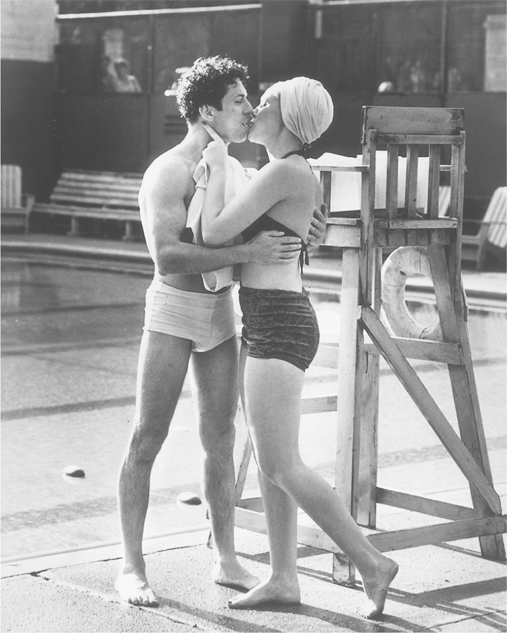

Jake’s exclusion from a lived reality is dramatized particularly in his relationship with women, characterized by an inability to respond to them as persons. It is one of the film’s finest achievements, given the extent to which it is centered on Jake’s consciousness, to convey to the audience (through the performance of Cathy Moriarty, but also through the very small role of Jake’s first wife) a female response that is shown simultaneously to be beyond Jake’s comprehension. For Jake, Vickie is from first to last an object, without independent existence. The film associates her repeatedly with swimming pools (the tenement pool where Jake first sees her, the pool of the home movies, the pool of their Miami home) and with the Lana Turner image (the most plastic and constructed of all the Hollywood star images): she is first shown posed by the pool in 1941, the release year of Honky Tonk, Johnny Eager, Ziegfeld Girl and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—the year of Turner’s rise to the position of major star and glamour symbol. The image is completed in the 1946 home movies (release year of The Postman Always Rings Twice) by her adoption of the famous white turban and sunsuit. Vickie is shown as at once complicit in her own objectification and yet having an existence outside it. In the course of the film Jake undergoes striking physical transformations (also made much of in the publicity surrounding De Niro) while Vicky remains unchanged, as Jake’s object/construction/possession. Specifically, Jake can’t relate to mature women or to women who demand recognition as autonomous beings (witness the casting off of the first wife). The scene in his Miami nightclub contrasts his flirtations with the teenage girls (who “prove” they’re not under age by kissing him) with his animus against mature women (when he kisses the state attorney’s wife he simultaneously upsets a drink all over her).

The film counterpoints two forms of violence: violence against women and violence against men, the latter subdivided between the socially licensed violence in the ring and the socially disapproved, spontaneous violence in public and private places outside the ring. While the motivations for these different manifestations of violence may seem quite distinct—Jake’s pursuit of a boxing career, his jealousy concerning Vickie—I think a true understanding of the film depends on our ability to grasp the relationship between them. The film suggests that there is quite clearly a connection: on two occasions, Jake’s fears of being overweight (i.e., of not being allowed to fight a man in the ring) are closely linked to another explosion of paranoid jealousy about (potential or actual violence toward) Vickie. Through a repeated motif the film also connects phallus and fist: Jake douses his cock with cold water to prevent himself reaching orgasm, and in a subsequent moment marked by a close-up plunges his fist into an ice bucket to cool it after a fight. Both forms of violence can in fact be interpreted as Jake’s defenses against the return of his repressed homosexuality, and I shall presently invoke Freud himself to demonstrate this. First, however, it is important to notice that the violence, though centered on Jake, is by no means exclusive to him but is generalized as a characteristic of the society, the product of its construction of sexual difference. It will be clear, also, that by “the society” I mean something much wider than the specific Italian-American subculture within which the film is set.

As a conclusion to his analysis of the Schreber case, Freud offers a general statement about paranoia and the principal forms of paranoid delusion that seems as relevant to the Jake La Motta of Raging Bull as to Senatspräsident Schreber:

We are in point of fact driven by experience to attribute to homosexual wishful phantasies an intimate (perhaps an invariable) relation to this particular form of disease. Distrusting my own experience on the subject, I have during the last few years joined with my friends C. G. Jung of Zurich and Sandor Ferenczi of Budapest in investigating upon this single point a number of cases of paranoid disorder which have come under observation. The patients whose histories provided the material for this enquiry included both men and women, and varied in race, occupation, and social standing. Yet we were astonished to find that in all of these cases a defence against a homosexual wish was clearly recognizable at the very centre of the conflict which underlay the disease, and that it was in an attempt to master an unconsciously reinforced current of homosexuality that they had all of them come to grief. (p. 196)

(Four pages later Freud throws out in the manner of a casual aside the remark that “a similar disposition would have to be assigned to patients suffering from … schizophrenia,” demonstrating that he had come close to a position where he was ready to posit repressed homosexuality as a major source of most serious mental illness.)

We can now consider the La Motta of Raging Bull in relation to the “forms of paranoia.” “The familiar principal forms of paranoia can all be represented as contradictions of the single proposition: ‘I love him’” (p. 200). Freud lists four of these forms, of which no less than three apply strikingly to Raging Bull; the fourth (the second of Freud’s categories) applies more tenuously but is not irrelevant.

1. “I do not love him—I hate him.” According to. Freud, this usually requires the pseudo-justification of delusions of persecution, as the hatred must be felt to be morally and rationally motivated (“I hate him because he persecutes me”). But it is precisely Jake’s profession that renders such a cover superfluous: as a boxer, he is licensed to express his animus against male bodies directly, and in public, before an approving audience. Two points need to be made here, that lead in somewhat opposed directions. First, Jake is presented as an exceptional case, a boxer noted not for his skill, grace, and agility, but for obsessive ferocity and excess. This of course confirms the Freudian diagnosis of La Motta as an individual “case,” but it may deflect us from the more general implications of boxing as a social institution. Therefore, as a second point, we should not lose sight of wider issues, though it is beyond the scope of the present article to pursue them far: I refer to the cultural significance of boxing itself as licensed and ritualized violence in which one man attempts to smash the near-naked body of another for the satisfaction (surely fundamentally erotic) of a predominantly male mass audience. It would be interesting to discover whether there is any significant correlation between an enthusiasm for boxing and homophobia.

2. The least relevant of Freud’s categories is what one might call the Don Juan syndrome where homosexuality is denied by means of obsessive pursuit of women (“I don’t love men—I love women”). Losey seems to have wanted to suggest something of this in his pretentious, humorless, strikingly de-eroticized and anti-Mozartian film of Don Giovanni. It is not presented as a prominent symptom of the La Motta case history, though strong traces of it manifest themselves in the later part of the film, in Jake’s need to be admired by women (especially attractive young women) in his nightclub, at the expense of Vickie and the domestic happiness constructed in the home movies. Three points: It is essential that this display take place in public: its motive is Jake’s preservation of an image as a man both attractive to and attracted by women, rather than any actual erotic satisfaction. The form it finally takes is Jake’s trick with the champagne glasses (a marvelously evocative image): the construction in public, before the admiring female gaze, of an imaginary phallus. (We discover subsequently that it is precisely during this action that Vickie is preparing finally to leave him.) The drive for women’s admiration manifests itself only after Jake has been denied the real erotic satisfaction (phallus/fist) of pummeling men in the ring. The public display of “I don’t love men—I hate them” gives way to the public display of “I don’t love men—I love women (and they love me).”

3. Freud’s final category contains his explanation of the close connection between paranoia and megalomania: the ultimate denial, “I don’t love at all,” in fact has its corollary “I love only myself”: megalomania is “a sexual overvaluation of the ego.” The relevance of this to La Motta seems obvious.

4. I have left to last what is actually the third of Freud’s categories, because, in relation to Raging Bull, it is the most resonant of all. This is the form of “sexual delusions of jealousy,” and we should not let ourselves be diverted from its implications by Freud’s association of it with alcohol, which is clearly inessential. He writes:

It is not infrequently disappointment over a woman that drives a man to drink—but this means, as a rule, that he resorts to the public-house and to the company of men, who afford him the emotional satisfaction which he has failed to get from his wife at home. If now these men become the objects of a strong libidinal cathexis in his unconscious he will ward it off with the third kind of contradiction: “It is not I who love the man—she loves him,” and he suspects the woman in relation to all the men whom he himself is tempted to love. (p. 202)

We can examine one manifestation of this last form of paranoia in the “Pelham, 1947” section of the film, the series of scenes that culminates in the Janiro fight. The structure is as follows: a. Domestic scene (Jake’s family, Joey’s family), linking Jake’s anxiety about his weight to his anxiety about Vickie. b. The Copacabana scene: Vickie is invited over to another table (presided over by Tommy, the “godfather” figure) and kissed by other men. This is followed by Jake’s obsessive questionings and distrust. He accepts the invitation to join the other men, and the conversation shifts to Janiro’s physical beauty. Jake remarks, as a joke, “I don’t know whether to fuck him or fight him.” c. At home, Jake awakens Vickie and resumes the interrogation about other men, finally attributing remarks about Janiro’s beauty to her. “I don’t even know what he looks like,” she replies. d. The fight: Jake deliberately destroys Janiro’s face, with a complicit smile at Vickie. He has effectively destroyed the threat Janiro posed, not as attractive to Vickie, but as attractive to himself.

This is perhaps the most obvious instance in the film of the kind of internal logic it is my purpose to trace; it is certainly not the only one. Near the beginning of the film, at the start of Jake’s career, we are confronted with his apparently irrational and never adequately explained hatred of Salvy, who is both a friend of Jake’s brother Joey and, because of his Mafia connections, a potential booster of Jake’s professional advancement. Salvy is with Vickie when Jake sees her for the first time at the tenement pool and immediately becomes fixated on her as an object. The film dramatizes here, very precisely, the relationship between “I don’t love him—I hate him” and “I don’t love him—I love her”—the possibility of movement from one of the forms of paranoia to another. Subsequently, Salvy becomes recruited into the ever growing ranks of men Jake believes Vickie to have had sex with.

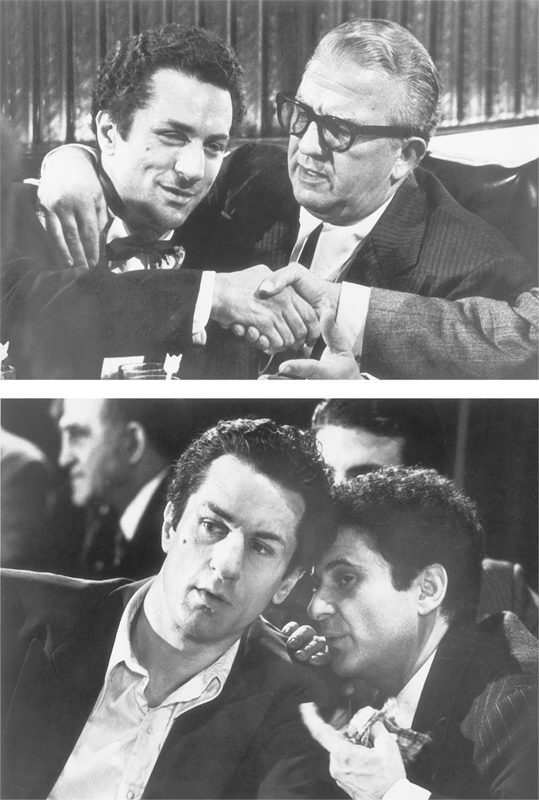

We must now confront one possible objection to this reading of La Motta, and of the film: apart from Janiro, with his disturbing physical beauty, and Salvy, with his florid good looks, the two men who precipitate Jake’s outbursts of paranoid jealousy are the sexually unattractive old man Tommy and Jake’s own brother Joey. Here we may have the film’s most remarkable insight and the one that will be hardest to accept. It is exactly at this point that the parallels between the film and Freud’s analysis of the Schreber case are most fascinating. Freud maintains that Schreber’s original love objects, for whom all later men were stand-ins, must have been his own father and brother. Tommy potently functions in the film as the father figure; Joey is Jake’s actual brother. The film’s insights, in fact, are closely in line with Freud’s insistence that erotic impulses take as their first objects the members of the immediate family circle (one might note here the closeness of Italian-American family relationships, while again rejecting any invitation to restrict the film’s implications to any specific milieu). What provokes the ultimate, cataclysmic explosion of Jake’s paranoid fantasy is Vickie’s defiant, sarcastic assertion that she sucked Joey’s cock.

We can now return to the principles of classical narrative, and especially the familiar one of closure: “the end answers the beginning.” Despite the frequent complaint that Scorsese lacks a sense of structure, Raging Bull relates to this formula very interestingly. The partial correspondence suggests, however, that the principles of symmetry and closure do not necessarily entail a restoration of the patriarchal order: rather, their function may be that of carefully marking the point the narrative has reached, by returning our memories to its starting point. One can single out the following points of reference:

1. The film (after the credits, before the final epigraph) begins and ends with Jake, fat, middle-aged, alone in his dressing room (1964) practicing his act. At the beginning of the film he is inarticulate, thoroughly incompetent, unable to master his lines, a potential laughingstock; at the end, he is able to deliver his monologue in a way that will at least not destroy his dignity.

2. Near the beginning, during the violent row between Jake and his first wife, an unseen neighbor shouts that they are “animals” (compare also the film’s title and Jake’s predilection for dressing in animal skins for his entries into the ring). This is followed immediately by the scene with Joey, shortly after Joey has raised the question of why Jake can’t stand Salvy, in which Jake demands that his brother punch him in the face. These moments are answered by the prison sequence near the end where Jake, in the most extreme instance of self-punishment, repeatedly beats his head against the wall of his cell after asserting “I’m not an animal,” and then by the scene in the garage to which he follows Joey, repeatedly embracing him and kissing him on the face. The moment can be read as an ironic inversion of the notion of the kiss as a privileged climactic moment of classical cinema, epitomizing the construction of the heterosexual couple.

3. We may also adduce here the moment at the beginning when Jake and Joey leave for the nightclub and Jake’s wife screams after him “Fucking queer.” The prison and garage scenes, in fact, answer all these moments from the beginning: if Jake behaves like an animal (violently, toward both men and women), it is because he is blocked from loving either; his insistence that Joey punch him in the face is answered by the embrace. The self-punishment motif, in relation to Joey, is not only taken up symmetrically at the end, it is also treated very thoroughly earlier, in the climactic fight with Robinson, the point of Jake’s retirement from the ring, which immediately follows his failure to apologize to Joey on the phone—the fight in which Jake allows himself to be beaten to a pulp, scarcely retaliating, with the one face-saving proviso that he was never knocked down.

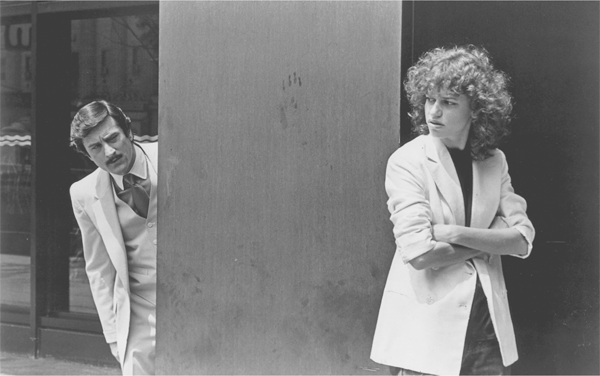

Raging Bull : Jake La Motta (Robert De Niro) with father figure (Nicholas Colasanto) … and brother (Joe Pesci)

This is one instance in the film where screen time takes precedence over narrative chronology: we don’t know how much time has elapsed between the abortive phone call and the Robinson fight, but in Scorsese’s montage the latter directly follows the former, obeying the inner logic of psychological movement. We have, finally, to confront the puzzle of the film’s end, which represents a more drastic use of the same license. At the opening of the film, Jake is patently incompetent, about to humiliate himself; at the end, he has mastered himself and his material (the On the Waterfront speech of Brando to Steiger in the taxi) sufficiently to maintain his dignity. The problem here—a very intriguing one—is of chronology. The film ends where it begins, in Jake’s dressing room. But is it the same night?—the film doesn’t tell us. Why is Jake totally incompetent at the start, adequate at the end?—the film doesn’t tell us. One is forced, I think, to posit two chronologies at work: the diegetic chronology (within which Jake’s transformation makes no sense whatever), and the actual movement of the film, in which the final scene directly follows the garage scene and the embrace. The film specifies a six-year gap between the two; the editing has one follow on from the other, as if its logical consequence. It is as if Scorsese wished simultaneously to assert and deny that the embrace was what made it possible for Jake to go through with his act—a speech, after all, about one brother’s unsatisfied emotional dependence upon another (“I could have been a contender … ”).

The narrative of Raging Bull, then, has its own inner logic, its own internal correspondences and interrelationships. Far from being a rambling and structureless stringing together of moments or a mere character study, it is among the major documents of our age: a work single-mindedly concerned with chronicling the disastrous consequences, for men and women alike, of the repression of constitutional bisexuality within our culture.

FATHER’S SHOES: SCORSESE’S RADICALISM

King of Comedy puzzled many people, including many of Scorsese’s admirers. Yes, the end more or less recapitulated the end of Taxi Driver, but otherwise, how does one relate it to the previous films? An anomaly, a dead end, a new departure? Certainly, it seemed at first glance a “minor” work, more limited in scope and ambition than any of its three narrative feature predecessors, and one of the problems of becoming a superstar director within the prevailing critical climate is that every work is expected to be “major.” Yet the attribution of minor status to the film now seems based partly on false assumptions (tragedy is major, comedy is minor), but more on a misconception of what the film actually does. It was generally taken at face value as a satire on notions of celebrity and an attack on the debasement of values within the mass media, specifically television. Of course, it is that. I want to argue here that it is also much more: one of the greatest, and certainly one of the most radical, American films about the structures of the patriarchal family. Viewed as such, the film immediately makes sense within the inner logic of the progress of Scorsese’s work, as a necessary follow-up to New York, New York and Raging Bull.

First, I should define what I mean here by radicalism. The films express no overt political commitment; one cannot take from them any coherently articulated Marxist critique of capitalism or feminist critique of patriarchy, and they give no reason to suppose that Scorsese would subscribe to either of those ideologies. One deduces from the films that his starting point is always an imaginative engagement with a subject, in the most concrete and specific sense: a character, a relationship, a situation; and, no doubt, perhaps simultaneously with the actors who will give them their dramatic embodiment. Yet every subject available must inevitably be structured by the major conflicts within the culture; what distinguishes the major artist is not an explicit ideological stance but his/her ability to pursue the implications of a given subject rigorously, honestly and without compromise, until its basis in those conflicts is revealed. Given that our culture is built upon interlocking structures of domination and oppression, such a pursuit (however innocent of any conscious ideological position) must inevitably produce radical insights—insights that can then be legitimately appropriated by overtly radical movements.

If I choose not to discuss New York, New York in these pages, this is purely because Richard Lippe has already done so.1 All great works constantly change their meanings or reveal new ones, in dynamic relationship with the historical/cultural situation within which they are perceived, and doubtless in the next decade further accounts of New York, New York will be needed; but for the moment, Lippe’s seems definitive. The film is exemplary of Scorsese’s method and of his radicalism. Starting from a subject in the concrete sense (relationship between a jazz saxophone player and a pop singer after the Second World War), the film gradually reveals its true subject—the impossibility of successful heterosexual relations within the existing sexual organization, with its construction of hopelessly incompatible gender roles. Perhaps the saddest moment in an overwhelmingly sad movie is one that Lippe does not, in fact, mention (it is virtually thrown away, as if it were of no significance—a phenomenon not uncommon in Scorsese’s work): the moment when the son of the impossible couple informs his father that he’s glad he takes after him because he wouldn’t want to be like a girl, and we see the whole sorry mess beginning again. New York, New York brilliantly describes; it doesn’t explain, beyond a fairly rudimentary level (e.g., men can’t live with women who are more successful than they are, they are afraid of being trapped in domesticity, and so on).

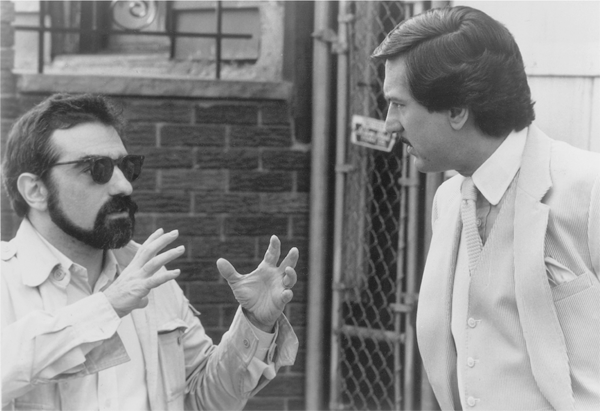

King of Comedy: Martin Scorsese directing Robert De Niro

The explanation is begun in Raging Bull, with its analysis of the construction of masculinity upon the basis of the repression of bisexuality, a masculinity that creates the man as a martyr as well as monster. Still lacking is an explanation of the role played in that construction by the family. Families are quite strikingly absent from Scorsese’s work. The only family in Taxi Driver is Iris’ (strictly off-screen and marginal); neither Jimmy Doyle nor Francine Evans appears to have any parents; Jake LaMotta’s are mentioned but never seen, and are allowed no explicit influence on the film’s events. It is as if Scorsese felt compelled to resist and repress any confrontation with the ways in which the individual is constructed within and by the family. It is not surprising that even in King of Comedy—which continues and extends the explanation of Raging Bull—he can approach the family only obliquely, albeit with the most extraordinary incisiveness and intransigence.

As with Raging Bull, whatever the film’s direct, unconscious impact, King of Comedy is accessible to interpretation only by the use of psychoanalytical theory; and the context within which I want to consider it is that of Freudian and post-Freudian accounts of the construction of children (male and female) within the structures of the patriarchal nuclear family. Crucial to that construction is what might be called the “battle for the phallus.” I discussed and I hope resolved, in the chapter on De Palma, the problems of this terminology: that the term “phallus,” like the term “castration,” must be understood as both literal and metaphorical, the latter usage being by far the more widespread and inclusive, but always carrying connotations of the fundamental meaning, which gives the terms their suggestive resonance. The phallus—penis, power, authority, domination, control of money, etc.—is the attribute of the Father (another literal/symbolic term); the mother is defined essentially by its absence. The little boy’s difficult and painful passage through the Oedipus and castration complexes (marked by a series of renunciations—his erotic attachments to both parents) leads to an “inevitable” resolution, against which homosexuality or neurosis is the only available form of revolt: he accepts symbolic castration, hence his powerlessness, on the understood condition that “one day” he will acquire the mother after all, in the form of a substitute woman. The logical corollary of this is that he learns to identify with the father, whom he will one day become. It follows from this that, from the moment of this identification and the simultaneous promise of possession of his own woman, the actual mother becomes increasingly irrelevant—a useless, castrated figure of no further significance; she might as well not exist. The little girl’s passage through socialization is perhaps even worse. From the outset, she must recognize that she can never “be” the father: her identification figure is, necessarily, the mother, who also represents to her her own castration. As she cannot hope to be the father, she can only hope, a least, to have him, again in the form of a substitute male, to whom she will offer her castrated person as a replica of the mother with whom she is forced to identify and whom she hates, both for the castration and the enforced identification.

Freud’s limitations cannot be stressed too often (neither can his greatness). He never fully confronted the horror of this process, the horror of the patriarchal family, because he could envisage no alternative to it. Today we can. Men and women can achieve equality, if women, and some men, are willing to fight hard enough for it, and “the phallus” can become quite simply the penis, all its metaphorical extensions stripped away, hopefully by mutual agreement. The “division of labor” can cease to exist, nurturing can become a function of men and women equally, and our long-repressed bisexuality can be reinstated. Meanwhile, despite the sweeping social changes that have occurred within the last few decades, we remain essentially within the situation Freud described: the present social/political/so-called moral climate is characterized by a desire to set us back in it permanently. Immediately relevant here is what underlies (and is produced by) this whole process of repression and socialization—a nausea and horror, originating in early infancy, which is never lost, a potential for rebellion which we may justly call instinctive, as its roots are in the pleasure principle with which we are born and the repression of most of its major and natural constituents. All this explains a phenomenon most of us recognize, emotionally if not intellectually, despite the pressures on us to not recognize it: the child’s simultaneous love and hate for its parents, inevitably carried over into adult life: the real subject of King of Comedy.

It is instructive at this point to introduce, for comparison, a film that I have already referred to in passing and which, as a phenomenon; has obvious symptomatic importance in the early 80s. Ordinary People belongs to sociology rather than aesthetics, which is to say that its interest lies, not in itself (it seems to me negligible) but in its great critical/commercial success. (But who, only a few years after its release, still talks about it? Who, two years from now, will still be talking about Terms of Endearment? The “masterpieces” that bourgeois journalism is able confidently to identify seldom prove to have much staying power.) Ordinary People is not, then, a film that demands detailed attention; indeed, it seems almost sufficient in this context merely to name it. The film belongs, unambiguously, to 80s reaction; its relevance here lies purely in its particularly precise and schematic, almost textbook, account of the Oedipal trajectory I have just described. The son progresses toward identification with the father, achieving this with the help of psychiatry (psychoanalysis institutionalized, conscripted into the service of the patriarchal order after being emptied of all its subversive content); the progress involves his acquisition of his own woman. The mother, redundant and inconvenient, can then be expelled from the narrative, leaving father and son in the plenitude of their Oedipal reconciliation. The film’s popularity, within its social context, was presumably due to its total complacency and complicity. If anything disturbs its equanimity it is, quite simply, the face of Mary Tyler Moore expressing the mother’s refusal to participate in or endorse a process that renders her superfluous. Otherwise, nothing in the film challenges or troubles: its quite insistent play on the emotions does not correspond to any disturbance of establishment values or dominant ideological assumptions. The ignominious position of women within the patriarchal family system is never acknowledged (if the mother can’t accept it, that’s her problem; the “nice girl” functions purely as support for the son and is given no autonomous existence whatever). The archetypal patriarchal resolution is offered without a hint of irony, criticism or complexity of attitude.

The distinction of King of Comedy is precisely that it subjects to rigorous, astringent, profoundly malicious analysis what Ordinary People reassuringly endorses and reinforces; the appearance of the film in the context of the 80s, in opposition to the whole movement of contemporary Hollywood cinema, testifies once again to Scorsese’s salutary intransigence. It is the most obviously economical of his films to date (though the occasional sense of redundancy and repetition in New York, New York and Raging Bull disappears when one grasps what the films are actually doing): every scene and every aspect have their precise place in the analysis. For this reason, it is convenient to break the film down into its components.

1. As a preliminary, we may note that Scorsese has implicitly acknowledged that this is a film about the family by including his own family in it: his sister is the autograph hunter who intrudes upon Rupert Pupkin’s fantasy lunch with Jerry Langford; his father is the man at the bar who objects to Rupert’s changing the television channel to the show on which he will appear; his mother (heard but not seen) is Rupert’s mother; Scorsese himself appears as the director of the Jerry Langford Show. Ambivalence—that simultaneous love and hate—toward the family could not be more succinctly epitomized: Scorsese expresses his affection for his family by putting them in his film, yet the subject of that film is the intrinsic monstrousness of the patriarchal family structures.

2. Rupert’s real father is absent from the film and is presumably dead. Jerry Langford functions both as a substitute father (because he is an actual person) and as the symbolic Father, (because of his prestige and authority as celebrity).

3. The projects of the “son” (Rupert) and the “daughter” (Masha) fit perfectly into the Oedipal pattern: Rupert wants to become the father (on whom he admits he has patterned his act) as the next “king of comedy.” Masha, on the other hand, shows no sign anywhere of wanting to achieve celebrity: her ambition is not to be the father but to have him.

4. Rupert perceives Rita as his woman, but he can claim her only when his identification with the father has been established, at least in fantasy: as soon as he can delude himself into believing that Langford has accepted him, he goes straight to Rita’s bar to establish possession, despite the fact that they haven’t met for so long that at first she doesn’t recognize him. Scorsese achieves here with Diahanne Abbott something of what he achieved with Cathy Moriarty in Raging Bull. The narrative is again completely male-dominated, which is to say not so much that men have the principal roles as that its every step is determined by the processes and concerns of patriarchy. Rita, accordingly, can function in it only as a pawn in the game, a token whose acquisition marks the male’s entry into the patriarchal order, rather than an autonomous human being. At the same time, Abbott is allowed (or encouraged) to bring to the role a degree of skepticism and resistance that repeatedly disturbs Rita’s overall complicity in the trajectory the film analyzes. She is conspicuously absent from the ending.

5. The culmination of this aspect of the film takes place, not as the traditional happy end, but as mere wish fulfillment: the wedding ceremony that Rupert fantasizes, staged and organized by the Father on his own talk show. The wish fulfillment is completed and the absurdity reinforced by the duplication of Langford with another father, Rupert’s high school principal (retired, now a Justice of the Peace), who not only performs the ceremony but clinches the fantasy with a public apology to Rupert for all the wrongs done him in his youth. The sequence enacts the impossible wish that the Father (here again both substitute and symbolic, patriarchy personified) should apologize for “the ignominy of boyhood.”

6. The film opens with Rupert’s imaginary identification with the father. The redundancy of the mother is signified in the most direct manner possible: she never appears in the movie, is reduced to an offscreen voice that gratingly intrudes on Rupert’s “important” and totally illusory pursuits. Thus disembodied and reduced to a mere incomprehending superfluous nuisance with no further role to play in the processes of patriarchy, she can then be killed off by Rupert in his climactic comic monologue (if his mother were here tonight “I’d say, ‘Mom, what are you doing here?, you’ve been dead nine years’ ”).

7. The visit to Langford’s country home, in response to an invitation issued within one of Rupert’s fantasies, and Rita’s participation in it are essential to Rupert’s project (and the failure of the visit is essential to the motivation of the rest of the narrative): the father must acknowledge the son, and the son’s acquisition of the woman (his accession to manhood), on his own territory, in his own home.

8. The kidnapping is provoked by the blocking of the two Oedipal projects: the humiliating defeat of the visit to Langford and Masha’s failure to get her love letter to him. “Brother” and “sister,” hostile to one another throughout the film, can precariously join forces in the frustration of their (superficially similar, profoundly incompatible) drives to possess the father.

9. There follows immediately, however, the extraordinary “sibling rivalry” sequence, in which the brother/sister antagonism resurfaces. The two compete, hilariously and pathetically, for the father’s attention as he is held at gunpoint (though even the gun is an illusion—they don’t really have the phallus). The means of gaining that attention vary significantly, however, corresponding precisely to the positions of the son and daughter within patriarchy: Rupert demands Langford’s interest in his tape (or rebukes him for his lack of it)—the tape is the evidence that he is the new king of comedy; Masha, on the other hand, woos Langford with the scarlet sweater she is knitting for him. They embody the drives that patriarchy constructs out of the free, indeterminate, bisexual libido with which we are born: to usurp the father’s position, to become his wife. Essential to both is the refusal to recognize Langford as a human individual: he is not a person but the phallus.

10. The ruthless logic with which Scorsese pursues his premises is exemplified again in the recognition that the Oedipal projects of the children can only be realized (in a way that simultaneously frustrates them) by reducing the father to total impotence, indeed, total immobility. The importance of the moment when Rupert begins actually to tape Langford to his chair, virtually mummifying him, so that he can barely even turn his head, is signaled by the film’s solitary recourse to an unusual camera angle: the overhead shot. It is the ultimate denial of Langford-as-person: he becomes an inanimate object who can then be supplanted by the son and made love to by the daughter.

11. With the father bound, Rupert can leave to become him on the show. (This is not of course strictly accurate: Langford’s literal replacement as host is Tony Randall. Yet the validity of the reading is not affected by this: in the conversation in Langford’s car at the beginning of the film Rupert makes it clear that his choice of Langford is dependent on the latter’s gifts as a comedian, and the casting of Jerry Lewis clinches the matter. We may further note that when Rupert finally leaves Langford outside his apartment building, the self-proclaimed future king of comedy already, in anticipation, demotes his predecessor: “Jerry, you’re a prince.”) Meanwhile Masha (in Sandra Bernhard’s astonishing incarnation) proceeds with her campaign to seduce the immobile and determinedly impassive father, first with a candlelight dinner, then with reminiscences of her real parents (“I never told my parents I loved them”—though she once carried golf clubs for her father, and Langford is a golfer), and finally with a romantic song, “Come Rain or Come Shine,” first heard over the opening credits sung by Ray Charles. The moment is one of the most extraordinary in a remarkably consistent, coherent, tightly organized film in which every moment is extraordinary: although Scorsese’s work has little discernibly in common with Brecht, a remarkable instance of “making the familiar strange.” The song, of a type our culture has come to take for granted, suddenly reveals previously unimagined meanings in the context within which it is performed. The intensity of the Oedipal investment is there in the opening “I’m gonna love you/like nobody’s loved you/come rain or come shine.” In fact, Masha commences the song with its later, corresponding verse, which gives us the other side of the impossible bargain: “You’re gonna love me/like nobody’s loved me.” The Oedipal basis of romantic love is cruelly, relentlessly exposed, the impossible demands that men and women, within our culture, make on one another related back to their roots in the overwhelming desires that patriarchy at once nurtures and frustrates.

12. Rupert arrives at the television studio, identifies himself as “the King,” and Miss Long, Langford’s secretary, for the first time gets his name right (he has previously been put through every variation: Pumpkin, Pipkin, Popkin). The name itself has obvious significance (the “pup” who insists on his “kin”-ship to the father). But it is only when Rupert becomes the father (the king) that his identity is at last established.

13. It is not enough that Rupert become the father: his woman must see that he has become it. Hence the necessity of transferring the spectacle of Rupert’s empty, barren triumph to Rita’s bar. She is even (as a woman under patriarchy, the barmaid, not the owner) impressed, though still skeptical.

14. The whole film moves—again, with that remorseless Scorsesian logic—to Rupert’s monologue, which is obsessively concerned with his parents. The mother, as already noted, is brutally eliminated (“dead nine years”). As for the father, Rupert is now standing in his shoes (metaphorically), and the monologue’s crowning joke is about his vomiting over them (literally): the son’s simultaneous love/hatred for the father could scarcely be more succinctly or more brilliantly expressed. Yet it can be argued that the film goes even beyond this statement of the filial ambivalence the patriarchal family engenders. The shoes that are vomited over are new shoes, the shoes Rupert is metaphorically now standing in. The hatred for the father whom he is obsessed with becoming is also, and crucially, self-hatred, self-contempt: the nausea the patriarchal process generates is ultimately nausea at oneself, as its latest recruit and representative.

King of Comedy

Father-fantasy (Jerry Lewis and Robert De Niro)

Robert De Niro and Sandra Bernhard

15. Langford’s presence (Lewis’ splendid performance, disciplined, precise, self-effacing) is itself eloquent: a pathetic, bitter, empty, totally isolated figure, he epitomizes the bankruptcy of patriarchy at this phase of consumer capitalism, the symbolic Father essentially meaningless and obsolete, though still hysterically pursued. The chain of “great” father figures that passes through the entire development of Hollywood cinema, endowed with attributes of moral/spiritual grandeur and divine authority (of which Abraham Lincoln, in his various cinematic incarnations, can stand as exemplary) has dwindled to a lonely, barren man in an immense apartment of cold glass and glitter. (For an alternative—parallel but very different—critique of the symbolic Father, the hero, see The Deer Hunter, discussed in the next chapter.)

16. Within the psychoanalytical context I have defined, the satire on the media takes on a resonance it entirely lacks when seen as the film’s sole and simple subject. Today, the media have become the vehicle for the perpetuation of patriarchy, a patriarchy emptied of its earlier force and potency, continuing as longed-for fantasy fulfillment (consider not only television, but the Star Wars phenomenon analyzed in a previous chapter). The ambivalence toward the Father inherent in the patriarchal family structure is repeated in the transference to the media: endless promise, endless frustration, since the promise can be fulfilled only in fantasy and one is always cheated. (The murder of John Lennon, which the film has been widely held to evoke, has its relevance here.)

17. The film’s rigorous attitude toward its characters makes possible the precisely focused irony of the ending, so similar to that of Taxi Driver yet so different. The absence of Schrader from the project is doubtless significant here: there is no suggestion of a drive toward a personal transcendence or redemption (never mind the cost). The absurdity of Rupert’s status as celebrity—the total emptiness of this new signifier of success, stardom, king, father—is firmly held. The emptiness of King of Comedy against the plenitude of Ordinary People: no wonder the public, the establishment press, the Motion Picture Academy, in short, America, preferred the latter. Yet it is the emptiness of Scorsese’s film that exposes the illusoriness of Ordinary People’s plenitude, by subjecting to analysis the structures through which it is achieved and the cost of the patriarchal process to the human psyche, both male and female.

1. Movie 31–32, pp. 95–100.