I dealt in chapter 6 with the first two films of George Romero’s “living dead” trilogy; the third, Day of the Dead (1985), had not then been made. The following account should be read in conjunction with the earlier chapter.

It is perhaps the lingering intellectual distrust of the horror genre that has prevented George Romero’s “living dead” trilogy from receiving full recognition for what it undoubtedly is: one of the most remarkable and audacious achievements of modern American cinema, and the most uncompromising critique of contemporary America (and, by extension, Western capitalist society in general) that is possible within the terms and conditions of a “popular entertainment” medium. Day is not merely the conclusion of the trilogy (which Romero has long planned to transform into a tetralogy, if he could raise the necessary finance); it is also its “clincher,” in many respects the most remarkable of the three films. One must, therefore, begin by accounting for its generally negative critical reception and its commercial failure, especially striking given the critical and popular success of Dawn of the Dead (1979).

Day belongs to the 80s as surely as Dawn to the 70s, but its relation to its period is quite different. Dawn was fully compatible with certain progressive aspects of its time, the period of the great radical movements (women’s liberation, the black movement, gay rights … ) that challenged the basic ideological assumptions of the culture. Day represents an uncompromisingly hostile response to the 80s, both to Reaganite America and to the cinema it produced. We can now look back on Dawn with a certain nostalgia for the exhilaration and excitement of a past age; Day is if anything more relevant today than it was when it appeared, as things have only got progressively blacker and more desperate, and events are currently escalating into a world situation of which the end of life on the planet (whether through nuclear war or the pollution of the environment) seems a not unlikely outcome.

The film’s resonance relates not only to the political evolution of America but to the evolution of its mainstream cinema. Since the Reaganite takeover and its increasingly reactionary sequels, Hollywood has become indeed the “Dream Factory” for which intellectuals always mistook it. Films are now financed, produced, and controlled largely by the massive corporations and conglomerates that are threatening our world with devastation in the interests of “making money”; the function of Hollywood has become simply that of “keeping people happy” and inhibiting thought. The contemporary “action” film—with its mind-numbing special effects, its computer-generated spectacle, its interminable mayhem, crashes, explosions, its reduction of what used to be characterization to expressions on actors’ faces, and above all its rapid editing that allows no breathing space for reflection—exemplifies merely one dismaying aspect among many: the teen films, the gross-out comedies, the painting-by-numbers romantic comedies … Day confronted not only the false, manufactured optimism of its period but also the cinema’s reinstatement of masculinism as a central issue: the Rockys, the Rambos, the Chuck Norris and Schwarzenegger movies, the popular response to feminism (accompanied by feminism’s gradual absorption, suitably modified, into the dominant ideology). It was the last film a public duped into heaving a vast communal sigh of relief that radicalism was no longer necessary wanted to see. On the topic of masculinity it is absolutely unequivocal.

In my discussion of the trilogy’s first two films I pointed out the triangular structure of the character-groups: in Night of the Living Dead (1968), zombies/besieged/sheriff’s posse; in Dawn of the Dead, zombies/besieged/motorcycle gang. Day repeats the structure but with somewhat different contents. Here, each member of the central group of sympathetic, progressive characters is initially attached to one of the three major groups (zombies/scientists/military): Sarah is a scientist, her lover Miguel a soldier; John, the West Indian, flies the military helicopter; the Irishman Bill McDermott is the electronics expert. All, in other words, are connected or belong to an authority group. In the course of the film they progressively dissociate themselves, by their actions and their attitudes, from these nominal allegiances, forming an oppositional group of their own.

The increasing bleakness and desperation of the trilogy—scarcely an unreasonable response to the Reagan era, and certainly not a hysterical one (Day is a perfectly controlled movie)—is marked most obviously by the increasing power of the zombies. In Night they could still, apparently, be contained (though the film’s attitude to the forces of containment remained resolutely negative and ironic); in Dawn they appeared to be getting the upper hand, though the surviving characters could still fly off, with the possibility that there might be somewhere safe where resistance was still feasible. In Day they have taken over the world, outnumbering the humans (according to calculations by Sarah’s immediate superior, Dr. Logan) by 400,000 to one; the only safe place left to fly to is a desert island that may exist only in fantasy. But perhaps the most significant progression from Dawn to Day lies in the images of money: in Dawn it was still worth helping oneself from the mall bank, “just in case”; in Day, money blows about the abandoned city streets, so much meaningless paper.

It was in Dawn that the zombies were first defined as “us,” and the definition is taken up in Day, though now only by the film’s monstrous scientist, embodying his “scientific” view of human nature. The implications of this definition need to be carefully pondered, as it is obviously both true and false. The zombies are human beings reduced to their residual “instincts”: they lack the functions that distinguish true humans, reason and emotion, the bases of human communication and human society. (The zombies throughout the trilogy never communicate, or even notice each other, except in terms of an automatic “herd” instinct, following the leader to the next food supply). The characters in all three films are valued precisely according to their potential to differentiate themselves from the zombies, their ability to demonstrate that the zombies are not in fact “us.” Something clearly needs to be said about my use of the term “residual instincts.” I am not referring here (and neither is the film, despite Dr. Logan’s commitment to such essentialist notions) to some God- or nature-given human essence. Certainly one might claim the need for food as a “natural” instinct, but Day is quite explicit on that score: “They don’t eat for nourishment.” What we popularly call “instincts” are in fact the product of our conditioning, and the residual instincts represented by the zombies are those conditioned by patriarchal capitalism. Above all, they consume for the sake of consuming (a revelation of Day—it was not apparent in the earlier films); all good capitalists are conditioned to live off other people, and the zombies simply carry this to its logical and literal conclusion. But it is through “Bub,” Dr. Logan’s prize zombie pupil, that the theme is most fully developed. What Bub learns, through a system of punishments (beatings) and rewards (raw human flesh) that effectively parodies the basis of our educational system, is “the bare beginnings of civilized behavior”: in fact, the conditioned reflex. It is Logan’s thesis—his hope for the human future—that the zombies can be trained, and to prove it he trains Bub to perform precisely the actions he was trained to perform in life, saluting and firing guns, subservience and violence, obeying orders without questioning them. The full savagery of the film’s irony can be gauged from the fact that Bub also responds, with the same automatism, to Beethoven’s “Choral” Symphony. Indeed, Schiller’s “Alle Menschen werden Bruder” takes on multiple ironic connotations in relation to all the film’s major groups—soldiers, scientists, zombies; and his (already thoroughly conditioned) sexism, which verbally excludes women from the universal “brotherhood,” receives its implicit answer in the trilogy’s progressive emphasis on women, to which I shall return.

First, however, I want to take up a point from the only review of Day of the Dead I can remember reading when the film appeared, in the Village Voice, in which the reviewer compared the film to Hawks’s splendid early 50s sci-fi movie The Thing from Another World, finding that Romero reverses Hawks’s values: the earlier film favored the military over the scientists, Day favors scientists over military. This rests, I think, on a serious misreading of both films, between which there is indeed a close relationship, one much more complex than that of simple opposition or reversal. Superficially, it is true that Hawks favors his military men (the airmen of the Arctic base) over at least his leading scientist Dr. Carrington (who has major characteristics in common with Dr. Logan), but they are favored not at all for militarism but for what they embody as human beings. Hawks downplays all sense of hierarchy (along with patriotism, which scarcely interests him at all): the men, whatever their rank, become individual and equally valued members of a typical Hawksian male group. What is celebrated in them (as also in the relationship between Captain Hendry and the woman Nikki) is their capacity for spontaneous affection and mutual respect, the pleasure in contact and communication that is fundamental to any valid community; they correspond, in fact, rather closely to Romero’s “good” characters, and not at all to his military men.

Romero, of course, being far more politically conscious than Hawks and working during the Reagan era, sees precisely what Hawks chose to ignore: the fact that the military is an institution, and one embodying in its extreme form the masculinism that pervades and structures the entire hierarchy of our culture. If Day as a whole must be read as a response to Reaganite America, its presentation of “masculinity” in its military characters is specifically a response to Reaganite cinema, the Rocky/Rambo syndrome. Day presents this in sexual terms (the overvaluation of the phallus, the obsession with “size”) and in more general terms of aggression and domination. As there is nothing subtle about the phenomenon, so there is nothing subtle about the presentation: masculinity, here, is rendered as caricature, grotesque and gross, the implication being that there is nothing more to be said about it. Is this presentation, in fact, any more gross than the general celebration of masculinity in the films of so many of Romero’s contemporaries? What Romero captures, magnificently, is the hysteria of contemporary masculinity, the very excesses of which testify to an anxiety, a terror. In Day, the grossness of the characters is answered, appropriately, by the grossness of their deaths: dismemberment and evisceration as the ultimate castration. The militarist mentality, and what it produces, gets its ironic comment when Bub, having shot Captain Rhodes (the group’s gung-ho military leader), dutifully salutes him as he is literally torn apart by the zombies.

That the film favors the scientists is, however, another misconception. It is true that Sarah, its most positive figure, is a scientist, just as Nikki in The Thing was associated with the scientists’ group (though in the subordinate role of secretary). Yet in both films the woman is valued partly for the way in which she dissociates herself from the values science embodies. “Science” in Day is “Dr. Frankenstein,” and it is revealed as yet another symbolic extension of masculinist ideology. If what distinguishes the human beings from the zombies is their potential for reason and emotion, then the science of Dr. Logan represents the overvaluation of a certain kind of rationality at the expense of other distinctively human qualities. The film is not exactly antiscience; neither, despite its reputation, was The Thing. In Hawks’s film the monster is finally destroyed by the functional use of scientific knowledge; in Day, technology and knowledge provide the means of escape, in the form of the helicopter and John’s ability to fly it. Both films make a similar distinction between knowledge placed at the service of human beings and knowledge as a means to power and domination: if “masculinity” as constructed within our culture has led to war, imperialism, the arms race, it has equally led to the domination—and destruction—of nature. Rationality has traditionally been claimed by men as an essentially male attribute, and as the justification for their power; women are fobbed off with “female intuition” as compensation. One can certainly argue that it is men who are the greater losers. The “rational,” from this point of view, is what the conscious mind works out for itself without assistance, while the “intuitive” is what the conscious mind comes to understand when it permits itself to remain in touch with the subconscious and with the emotional levels of human psychic activity. Dr. Logan’s science is rational in this limited and limiting sense, its results disgusting, dehumanizing, and ultimately useless (the film presents him as increasingly bloodsoaked as the action progresses). On the other hand, there is nothing irrational about the decisions and actions of the positive characters: like the sympathetic characters of The Thing, they simply permit their reason to remain in touch with actual human needs.

Day of the Dead

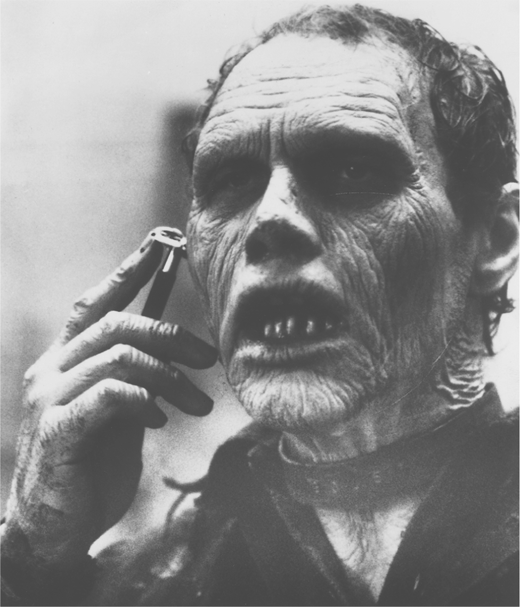

Bub (Howard Sherman) learns to shave

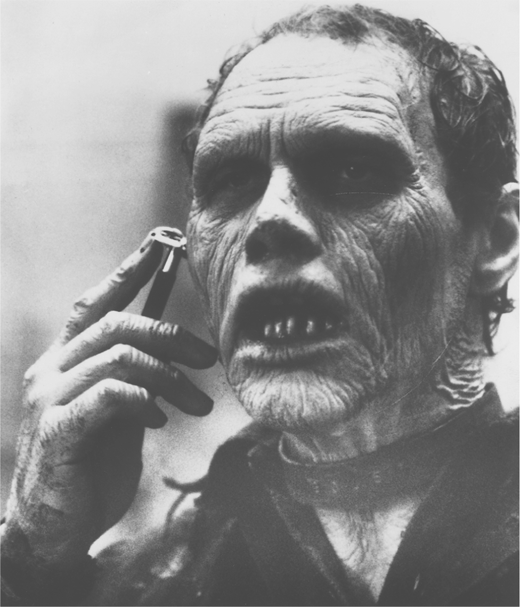

Captain Rhodes (Joseph Pilato) tries (unsuccessfully) to intimidate Sarah (Lori Cardille)

Central to the trilogy’s progress is the development throughout the three films of the female protagonists. Barbara in Night becomes virtually catatonic early on and remains so throughout the action, a parody of female passivity and helplessness; Fran in Dawn is at first thoroughly complicit in the established structures of heterosexuality, then learns gradually to assert herself and extricate herself from them. In Day the woman has become, quite unambiguously, the positive center around whom the entire film is structured. Strikingly androgynous in character, she combines without strain the best of those qualities our culture has traditionally separated out as “masculine” and “feminine”: strong, decisive, and resourceful, she is also tender and caring, and shows no desire to dominate. As a scientist, she wants to understand what has produced the zombies so that the process might be reversed; Logan wants to control the zombies, turning them into his slaves and the proof of his theories. Initially antagonistic, Sarah progressively associates herself with the two men who have opted out of the military-versus-scientist conflict; she effectively learns, in fact, to abandon any attempt to save American civilization, which the film characterizes as a waste of time. Her lover, Miguel, is the least masculine of the soldiers, tormented indeed (partly under the goads of the other men) by the failure of his masculinity, and provoking disasters by his attempts to reassert it.

Day of the Dead

The zombies in need of sustenance

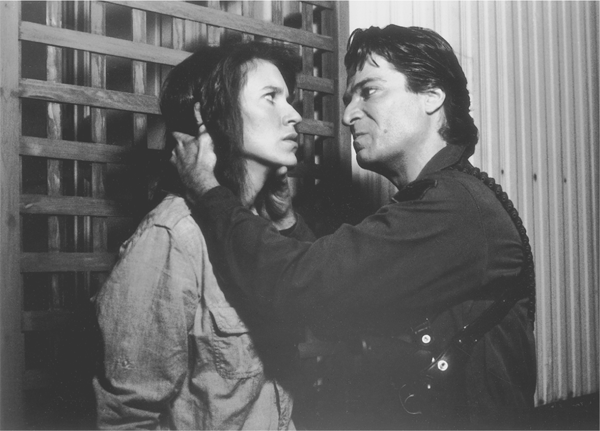

The death of Miguel (Antone DiLeo)

The film begins and ends with Sarah awakening from a nightmare of being assaulted by the zombies: the overtones of rape link the zombies to the military, who repeatedly threaten her with exactly that. This formal device produces complicated narrative ambiguities. We are given no clear sense of where the final nightmare begins (the zombies are inside the helicopter, and attack Sarah as she climbs in): it is possible to read the entire film as the woman’s nightmare, with the exception of the brief coda where Sarah wakes up on the beach of a tropical island, the two men fishing nearby (though, paradoxically, that ending validates the nightmare’s reality). However, the abruptness and implausibility of this “happy ending” (a striking example of what Sirk called the “emergency exit”) encourages an opposite reading: the body of the film is the reality, the epilogue a wish-fulfillment fantasy (perhaps Sarah’s fantasy as she dies, perhaps simply the filmmaker’s ironic commentary—the island image forms part of the décor of John’s room in the underground shelter). Romero allows us a tentative and qualified optimism if we wish: the final image relates back to John’s solution, that they fly away to a desert island and have babies who will be reared without ever even having to know that the whole legacy of American culture existed. (“Teach them never to come here and dig those records out”—the records of “the top five hundred companies, the defense department budget, the negatives of all your favorite movies”—effectively, the records of the economic/political base and the ideological superstructure of American capitalism: “This is a great big fourteen-mile tombstone with an epitaph on it that nobody’s going to bother to read.”) “Qualified” optimism at best: the zombies have taken over the entire world and, while they can’t reproduce, they appear not to die unless deliberately slaughtered; and the notion of flying away to a desert island is established, near the film’s beginning, as a form of hedonistic escapism. The ambiguity renders even this limited hope for any human future tentative and dubious, and we are permitted no hope whatever for American (Western capitalist, masculinist) civilization. It was an extraordinary film to come upon in the midst of the Rockys, the Rambos, the Back to the Futures, that dominated the era; it still seems extraordinary today

To me it is a matter of some urgency (if one retains any faith in the power of art to effect change) that Day of the Dead receive at last the attention and respect it deserves. It is if anything more important today than it was when it was made. If not quite about the end of the world, it is clearly about the end of ours, which it now seems that little short of a universal miracle can prevent.